John Whitgift on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Whitgift (c. 1530 – 29 February 1604) was the

Whitgift's theological views were controversial. An aunt with whom he once lodged wrote that "though she thought at first she had received a saint into her house, she now perceived he was a devil".

Whitgift's theological views were controversial. An aunt with whom he once lodged wrote that "though she thought at first she had received a saint into her house, she now perceived he was a devil".

In August 1583 he was appointed

In August 1583 he was appointed

The Master of Trinity

at

''The Life and Acts of John Whitgift, D.D.'', Volume I

by John Strype (1822 ed.)

''The Life and Acts of John Whitgift, D.D.'', Volume II

by John Strype (1822 ed.)

''The Life and Acts of John Whitgift, D.D.'', Volume III

by John Strype (1822 ed.)

The Whitgift Foundation

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Whitgift, John 1530s births 1604 deaths 16th-century Church of England bishops Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Alumni of Queens' College, Cambridge Fellows of Peterhouse, Cambridge Founders of English schools and colleges Masters of Pembroke College, Cambridge Masters of Trinity College, Cambridge Archbishops of Canterbury Bishops of Worcester People from Grimsby English philanthropists Deans of Lincoln Burials at Croydon Minster Vice-chancellors of the University of Cambridge Lady Margaret's Professors of Divinity Regius Professors of Divinity (University of Cambridge) 17th-century Anglican theologians 16th-century Anglican theologians Year of birth uncertain

Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

from 1583 to his death. Noted for his hospitality, he was somewhat ostentatious in his habits, sometimes visiting Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

and other towns attended by a retinue of 800 horses. Whitgift's theological views were often controversial.

Early life and education

He was the eldest son of Henry Whitgift, a merchant, of GreatGrimsby

Grimsby or Great Grimsby is a port town in Lincolnshire, England with a population of 86,138 (as of 2021). It is located near the mouth on the south bank of the Humber that flows to the North Sea. Grimsby adjoins the town of Cleethorpes dir ...

, Lincolnshire, where he was born, probably between 1530 and 1533. The Whitgift family is thought to have originated in the relatively close Yorkshire village of Whitgift, adjoining the River Ouse.

Whitgift's early education was entrusted to his uncle, Robert Whitgift, abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

of the neighbouring Wellow Abbey, on whose advice he was sent to St Anthony's School, London. In 1549 he matriculated at Queens' College, Cambridge

Queens' College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Queens' is one of the 16 "old colleges" of the university, and was founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou. Its buildings span the R ...

, and in May 1550 he moved to Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, where the martyr John Bradford

John Bradford (1510–1555) was an English English Reformation, Reformer, prebendary of Old St Paul's Cathedral, St. Paul's, and martyr. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London for alleged crimes against Queen Mary I. He was burned at the stak ...

was his tutor. In May 1555 he was elected a fellow of Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Peterhouse has around 300 undergraduate and 175 graduate stud ...

.

Links with Cambridge

Having taken holy orders in 1560, he became chaplain to Richard Cox, Bishop of Ely, who collated (that is, appointed) him to the rectory of Teversham, just to the east ofCambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. In 1563 he was appointed Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, and his lectures gave such satisfaction to the authorities that on 5 July 1566 they considerably augmented his stipend. The following year he was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity

The Regius Professorships of Divinity are amongst the oldest professorships at the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge. A third chair existed for a period at Trinity College Dublin.

The Oxford and Cambridge chairs were founded by ...

, and became master first of Pembroke Hall (1567) and then of Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

in 1570. He had a principal share in compiling the statutes of the university, which passed the great seal

A great seal is a seal used by a head of state, or someone authorised to do so on their behalf, to confirm formal documents, such as laws, treaties, appointments and letters of dispatch. It was and is used as a guarantee of the authenticity of ...

on 25 September 1570, and in the November following he was chosen as vice-chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

.

While at Cambridge he formed a close relationship with Andrew Perne, sometime vice-chancellor. Perne went on to live with Whitgift in his old age. Puritan satirists would later mock Whitgift as "Perne's boy" who was willing to carry his cloak-bag – thus suggesting that the two had enjoyed a homosexual relationship.

Francis Bacon

Whitgift taughtFrancis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

and his older brother Anthony Bacon at Cambridge University in the 1570s. As their tutor, Whitgift bought the brothers their early classical text books, including works by Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and others.

Whitgift's authoritarian beliefs and conservative religious teachings had a profound impact on Bacon, as did his teaching on natural philosophy and metaphysics.

Bacon would later disavow Whitgift, writing to Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

to warn her against Whitgift's attempts to root out the "careful and diligent preachers in each parish".

Promotions and improvements

Whitgift's theological views were controversial. An aunt with whom he once lodged wrote that "though she thought at first she had received a saint into her house, she now perceived he was a devil".

Whitgift's theological views were controversial. An aunt with whom he once lodged wrote that "though she thought at first she had received a saint into her house, she now perceived he was a devil". Thomas Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was an English historian, poet, and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster General between 184 ...

's description of Whitgift as "a narrow, mean, tyrannical priest, who gained power by servility and adulation..." is, according to the author of his 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

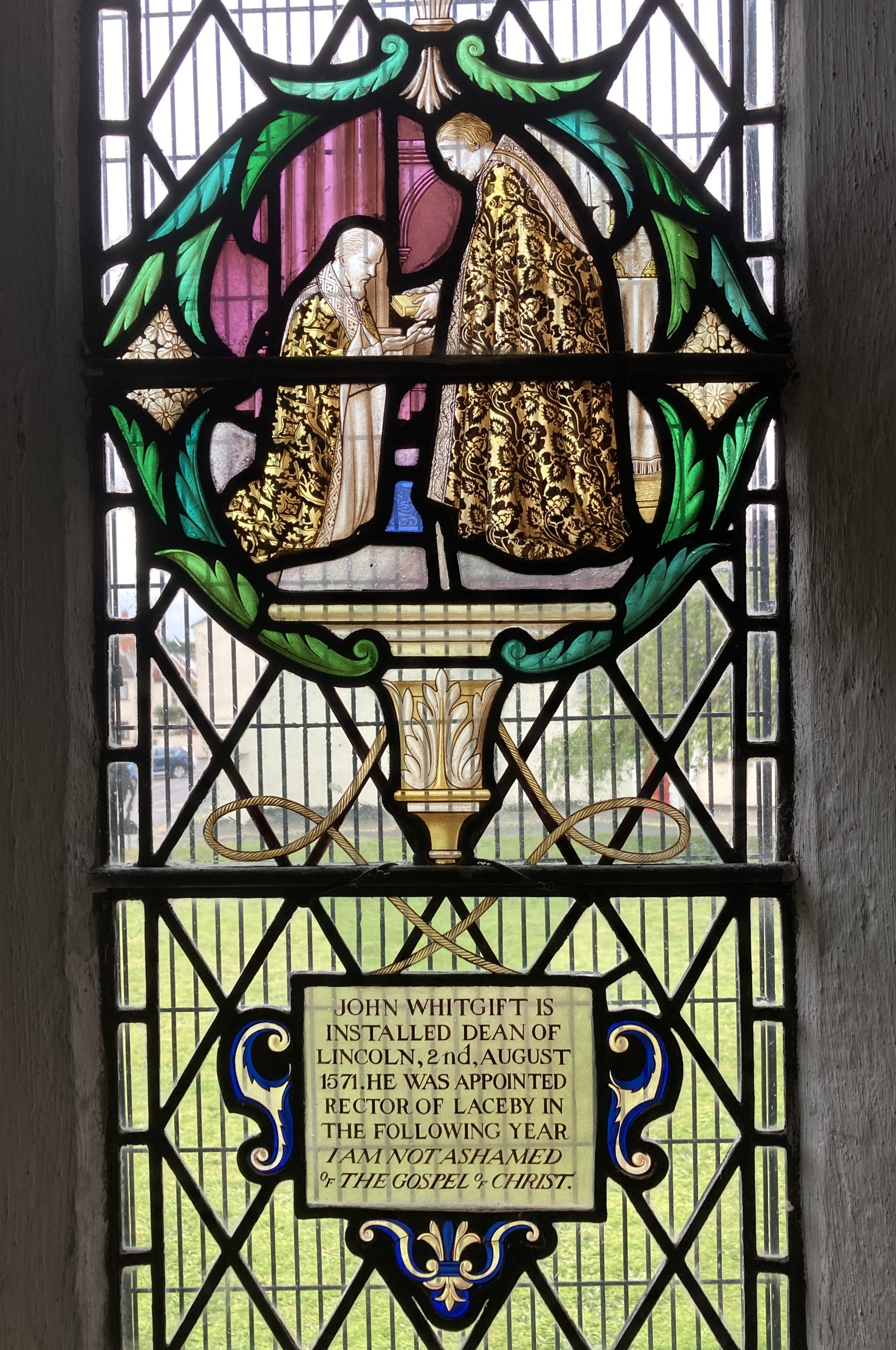

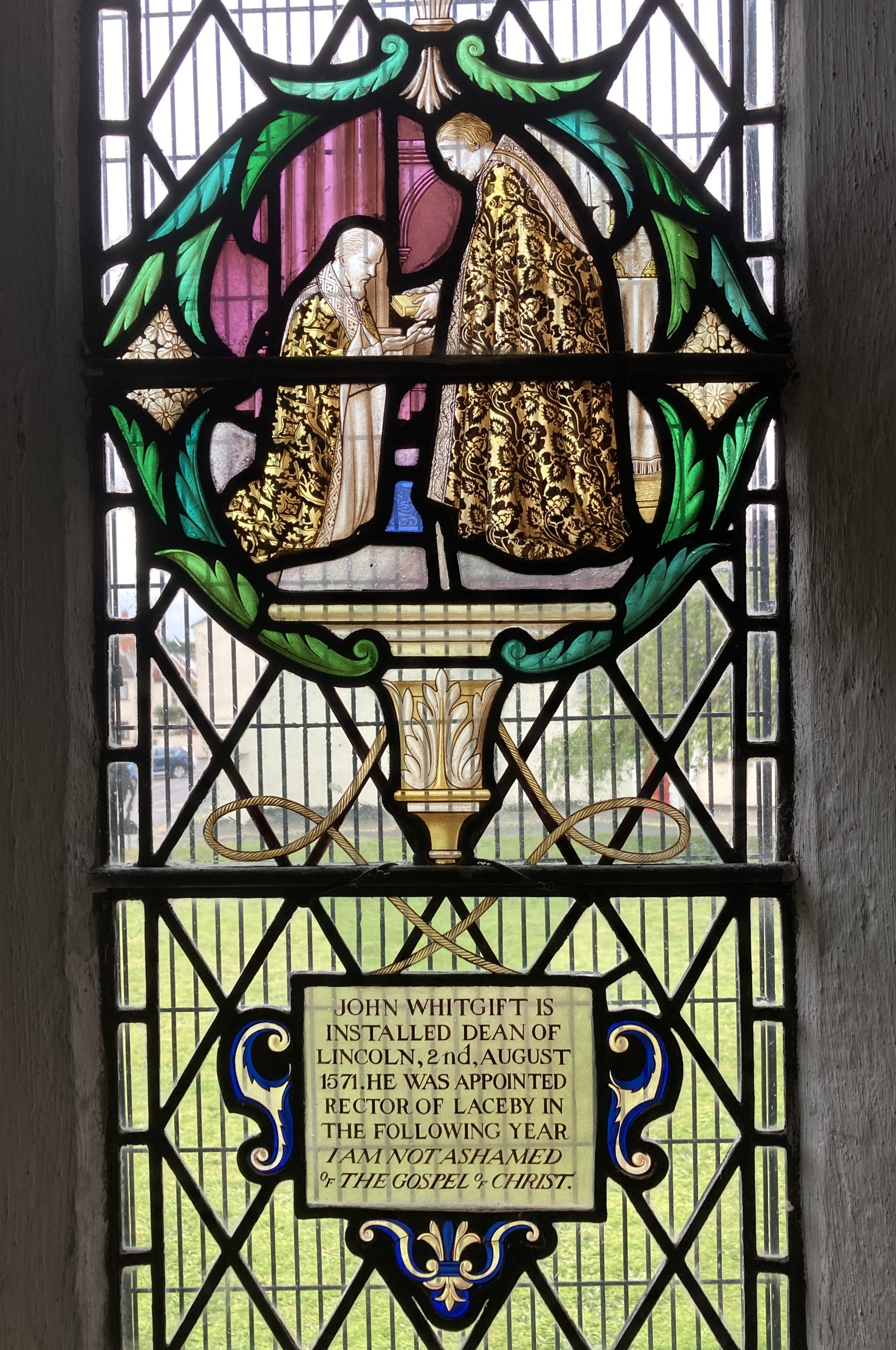

'' entry, "tinged with rhetorical exaggeration; but undoubtedly Whitgift's extreme High Church notions led him to treat the Puritans with exceptional intolerance". In a pulpit controversy with Thomas Cartwright regarding the constitutions and customs of the Church of England, his oratorical effectiveness proved inferior, but he was able to exercise arbitrary authority: together with other heads of the university, he deprived Cartwright of his professorship, and in September 1571 Whitgift exercised his prerogative as master of Trinity to strip him of his fellowship. In June of the same year Whitgift was nominated Dean of Lincoln. In the following year he published ''An Answere to a Certain Libel'' entitled an ''Admonition to the Parliament'', which led to further controversy between the two churchmen. From 1572 to 1577 he was Rector of St Margaret's church in Laceby in Lincolnshire. On 24 March 1577, Whitgift was appointed Bishop of Worcester

The Bishop of Worcester is the Ordinary (officer), head of the Church of England Anglican Diocese of Worcester, Diocese of Worcester in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title can be traced back to the foundation of the diocese in the ...

, and during the absence of Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586) was an English soldier, politician and Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Background

He was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst (1482 – 11 February 1553) and Anne Pakenham (1511 – 22 Oc ...

in Ireland in 1577 he acted as vice-president of Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

.

Archbishop of Canterbury, 1583–1604

In August 1583 he was appointed

In August 1583 he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

to replace Edmund Grindal, who had been placed under house arrest after his disagreement with Queen Elizabeth over "prophesyings" and died in office. Whitgift placed his stamp on the church of the Reformation, and shared Elizabeth's hatred of Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

. Although he wrote to Elizabeth remonstrating against the alienation of church property, Whitgift always retained her special confidence. In his policy against the Puritans and in his vigorous enforcement of the subscription test he thoroughly carried out her policy of religious uniformity.

He drew up articles aimed at nonconforming ministers, and obtained increased powers for the Court of High Commission

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and administer justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law.

Courts gene ...

. In 1586, he became a privy councillor. His actions gave rise to the Martin Marprelate tracts, in which the bishops and clergy were strongly opposed. By his vigilance the printers of the tracts were discovered and punished, though the main writer Job Throkmorton evaded him. Whitgift had nine leading presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

including Thomas Cartwright arrested in 1589–90, and though their trial in the Star Chamber for sedition did not result in convictions they did agree to abandon their movement in return for freedom.

Whitgift took a strong line against the Brownist movement and their Underground Church in London led by Henry Barrow and John Greenwood. Their services were repeatedly raided and members held in prison. Whitgift repeatedly interrogated them through the High Commission, and at the Privy Council. When Burghley asked Barrow his opinion of the Archbishop, he responded: "He is a monster, a miserable compound, I know not what to make him. He is neither ecclesiastical nor civil, even that second beast spoken of in revelation." Whitgift was the prime mover behind the Act against Seditious Sectaries which was passed in 1593, making Separatist Puritanism a felony, and he had Barrow and Greenwood executed the following morning.

In the controversy between Walter Travers and Richard Hooker

Richard Hooker (25 March 1554 – 2 November 1600) was an English priest in the Church of England and an influential theologian.''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' by F. L. Cross (Editor), E. A. Livingstone (Editor) Oxford Univer ...

, he prohibited the former from preaching, and he presented the latter with the rectory of Boscombe in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

, to help him complete his ''Ecclesiastical Polity'', a work that in the end did not represent Whitgift's theological or ecclesiastical standpoints. In 1587, he had Welsh preacher John Penry

John Penry (1563 – 29 May 1593) was executed for high treason during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. He is Wales' most famous Protestant Separatist martyr.

Early life

Penry was born in Brecknockshire, Wales; Cefn Brith, a farm near Llangamma ...

brought before the High Commission, and imprisoned; Whitgift signed Penry's death warrant six years later.

In 1595, in conjunction with the Bishop of London and other prelates, he drew up the Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

instrument known as the Lambeth Articles. Although the articles were signed and agreed by several bishops they were recalled by order of Elizabeth, claiming that the bishops had acted without her explicit consent. Whitgift maintained that she had given her approval.

Whitgift attended Elizabeth on her deathbed, and crowned James I. He was present at the Hampton Court Conference

The Hampton Court Conference was a meeting in January 1604, convened at Hampton Court Palace, for discussion between King James I of England and representatives of the Church of England, including leading English Puritans. The conference resulted ...

in January 1604, at which he represented eight bishops.

He died at Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

at the end of the following month. He was buried in Croydon at the Parish Church of St John Baptist (now Croydon Minster): his monument there with his recumbent effigy was practically destroyed when the church burnt down in 1867.

Legacy

Whitgift is described by his biographer, Sir George Paule, as of "middle stature, strong and well shaped, of a grave countenance and brown complexion, black hair and eyes, his beard neither long nor thick." He left several unpublished works, included in the ''Manuscripts Angliae''. Many of his letters, articles and injunctions are calendared in the published volumes of the ''State Papers'' series of the reign of Elizabeth. His ''Collected Works'', edited for theParker Society The Parker Society was a text publication society set up in 1841 to produce editions of the works of the early Protestant writers of the English Reformation. It was supported by both the High Church and evangelical wings of the Church of England, an ...

by John Ayre (3 vols., Cambridge, 1851–1853), include the controversial tracts mentioned above, two sermons published during his lifetime, a selection from his letters to Cecil and others, and some portions of his previously unpublished manuscripts.

In his later years he concerned himself with various administrative reforms, including fostering learning among the clergy, abolishing non-resident clergy, and reforming the ecclesiastical courts.

Whitgift set up charitable foundations (almshouses), now The Whitgift Foundation, in Croydon

Croydon is a large town in South London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a Districts of England, local government district of Greater London; it is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater Lond ...

, the site of a palace, a summer retreat of Archbishops of Canterbury. It supports homes for the elderly and infirm, and runs three independent schools – Whitgift School

Whitgift School is an independent day school with limited boarding in South Croydon, London. Along with Trinity School of John Whitgift and Old Palace School it is owned by the Whitgift Foundation, a charitable trust. The school was prev ...

, founded in 1596, Trinity School of John Whitgift

The Trinity School of John Whitgift, also known as Trinity School, is a independent boys' day school with a co-educational sixth form, located in Shirley Park, Croydon. Part of the Whitgift Foundation, it was established in 1882 as Whitgift ...

and, more recently, Old Palace School for girls, which is housed in the former Croydon Palace.

Whitgift Street near Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament of the United King ...

(the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury) is named after him. Whitgift Close in Laceby in Lincolnshire, where he was Rector of St Margaret's church from 1572 to 1577, is also named for him.

A comprehensive school in his home town of Grimsby, John Whitgift Academy, is named after him.

The Whitgift Centre, a major shopping centre in Croydon, is named after him. It is built on land still owned by the Whitgift Foundation.

In media

Season 7, Episode 6 of the Bad Gays podcast covers his life.References

Sources

* * Whitgift, John, ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' edited by F. L. Cross, (1957). *''Life of Whitgift'' by Sir George Paule, 1612, 2nd ed. 1649. It was embodied by John Strype in his ''Life and Acts of Whitgift'' (1718). *A life included in Wordsworth's ''Ecclesiastical Biography'' (1810) * W. F. Hook, ''Archbishops of Canterbury'' (1875) *Vol. i. of Whitgift's ''Collected Works'' *C. H. Cooper

Charles Henry Cooper (20 March 180821 March 1866) was an English antiquarian.

Life

Born at Marlow, Buckinghamshire, Marlow, Buckinghamshire, he was descended from a family formerly of Bray, Berkshire, Bray in Berkshire. He was privately educate ...

, ''Athenae Cantabrigienses''.The Master of Trinity

at

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

*

*

External links

''The Life and Acts of John Whitgift, D.D.'', Volume I

by John Strype (1822 ed.)

''The Life and Acts of John Whitgift, D.D.'', Volume II

by John Strype (1822 ed.)

''The Life and Acts of John Whitgift, D.D.'', Volume III

by John Strype (1822 ed.)

The Whitgift Foundation

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Whitgift, John 1530s births 1604 deaths 16th-century Church of England bishops Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Alumni of Queens' College, Cambridge Fellows of Peterhouse, Cambridge Founders of English schools and colleges Masters of Pembroke College, Cambridge Masters of Trinity College, Cambridge Archbishops of Canterbury Bishops of Worcester People from Grimsby English philanthropists Deans of Lincoln Burials at Croydon Minster Vice-chancellors of the University of Cambridge Lady Margaret's Professors of Divinity Regius Professors of Divinity (University of Cambridge) 17th-century Anglican theologians 16th-century Anglican theologians Year of birth uncertain