John Ireland (bishop) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Ireland (baptized September 11, 1838 – September 25, 1918) was an American prelate who was the third

John Ireland was born in Burnchurch,

John Ireland was born in Burnchurch,

/ref> He was the second of seven children born to Richard Ireland, a carpenter, and his second wife, Judith Naughton. His family immigrated to the United States in 1848 and eventually moved to

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical

At the

At the

BioIreland, John (1838–1918)

MNopedia. *

Bishop Ireland's Connemara Experiment:

''

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

bishop and first archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota (1888–1918). He became both a religious as well as civic leader in Saint Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world. For his contributions towards the New Testament, he is generally ...

during the turn of the 20th century. Ireland was known for his progressive stance on education, immigration and relations between church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

, as well as his opposition to saloons, alcoholism

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World He ...

, political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

s, and political corruption

Political corruption is the use of powers by government officials or their network contacts for illegitimate private gain. Forms of corruption vary but can include bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, influen ...

.

He promoted the Americanization

Americanization or Americanisation (see spelling differences) is the influence of the American culture and economy on other countries outside the United States, including their media, cuisine, business practices, popular culture, technology ...

of Catholicism, especially through imposing the English only movement

The English-only movement, also known as the Official English movement, is a political movement that advocates for the exclusive use of the English language in official United States government communication through the establishment of English ...

on Catholic parishes by force, a private war against the Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, seeking to make Catholic school

Catholic schools are Parochial school, parochial pre-primary, primary and secondary educational institutions administered in association with the Catholic Church. , the Catholic Church operates the world's largest parochial schools, religious, no ...

s identical to public schools through the Poughkeepsie plan, and through other progressive social ideas. He was widely considered the primary leader of the modernizing element in the Catholic Church in the United States

The Catholic Church in the United States is part of the worldwide Catholic Church in full communion, communion with the pope, who as of 2025 is Chicago, Illinois-born Pope Leo XIV, Leo XIV. With 23 percent of the United States' population , t ...

during the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was a period in the United States characterized by multiple social and political reform efforts. Reformers during this era, known as progressivism in the United States, Progressives, sought to address iss ...

, which brought him into open conflict over minority language rights and theology with both his suffragen Bishop Otto Zardetti and eventually with Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

, whose Apostolic letter ''Testem benevolentiae nostrae

''Testem benevolentiae nostrae'' is an apostolic letter written by Pope Leo XIII to Cardinal James Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, dated January 22, 1899. In it, the pope addressed a heresy that he called Americanism and expressed his concern ...

'' condemned Archbishop Ireland's ideas as the heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

of Americanism. He also created or helped to create many religious and educational institutions in Minnesota.

History

John Ireland was born in Burnchurch,

John Ireland was born in Burnchurch, County Kilkenny

County Kilkenny () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is named after the City status in Ir ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, and was baptized on September 11, 1838.Shannon, J. P. "Ireland, John" ''New Catholic Encyclopedia'', Vol. 7. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003/ref> He was the second of seven children born to Richard Ireland, a carpenter, and his second wife, Judith Naughton. His family immigrated to the United States in 1848 and eventually moved to

Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (often abbreviated St. Paul) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County, Minnesota, Ramsey County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, ...

, in 1852. One year later Joseph Crétin

Joseph Crétin (December 19, 1799 – February 22, 1857) was an American Catholic prelate who was the first Roman Catholic Bishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota. Cretin Avenue in St. Paul, Cretin-Derham Hall High School, and Cretin Hall at the Univer ...

, first bishop of Saint Paul, sent Ireland to the preparatory seminary of Meximieux

Meximieux () is a commune in the Ain department in eastern France.

Geography

Located 35 km north east of Lyon and 10 km south west Ambérieu-en-Bugey, the town is where the Dombes plateau meets the plain of the river Ain. Historic ...

in France. Ireland was consequently ordained in 1861 in Saint Paul. He served as a chaplain of the Fifth Minnesota Regiment in the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

until 1863 when ill health caused his resignation. Later, he was famous nationwide in the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (United States Navy, U.S. Navy), and the United States Marine Corps, Marines who served in the American Ci ...

.

He was appointed pastor at Saint Paul's cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

in 1867, a position which he held until 1875. In 1875, he was made coadjutor bishop

A coadjutor bishop (or bishop coadjutor) ("co-assister" in Latin) is a bishop in the Latin Catholic, Anglican and (historically) Eastern Orthodox churches whose main role is to assist the diocesan bishop in administering the diocese.

The coa ...

of St. Paul and in 1884, he became bishop ordinary. In 1888, he became archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

with the elevation of his diocese and the erection of the ecclesiastical province of Saint Paul. Ireland retained this title for 30 years until his death in 1918. Before Ireland died he burned all his personal papers.Empson, ''The Streets Where You Live'', 144 He was buried in Calvary Cemetery.

Ireland was personal friends with Presidents William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. At a time when most Irish Catholics were staunch Democrats, Ireland was known for being close to the Republican party. Privately Ireland would tell people he was a member of the party. He opposed racial inequality

Social inequality occurs when resources within a society are distributed unevenly, often as a result of inequitable allocation practices that create distinct unequal patterns based on socially defined categories of people. Differences in acce ...

and called for "equal rights and equal privileges, political, civil, and social."

Ireland's funeral was attended by eight archbishops, thirty bishops, twelve monsignors, seven hundred priests and two hundred seminarians.

He was awarded an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

(LL.D.

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

) by Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

in October 1901, during celebrations for the bicentenary of the university.

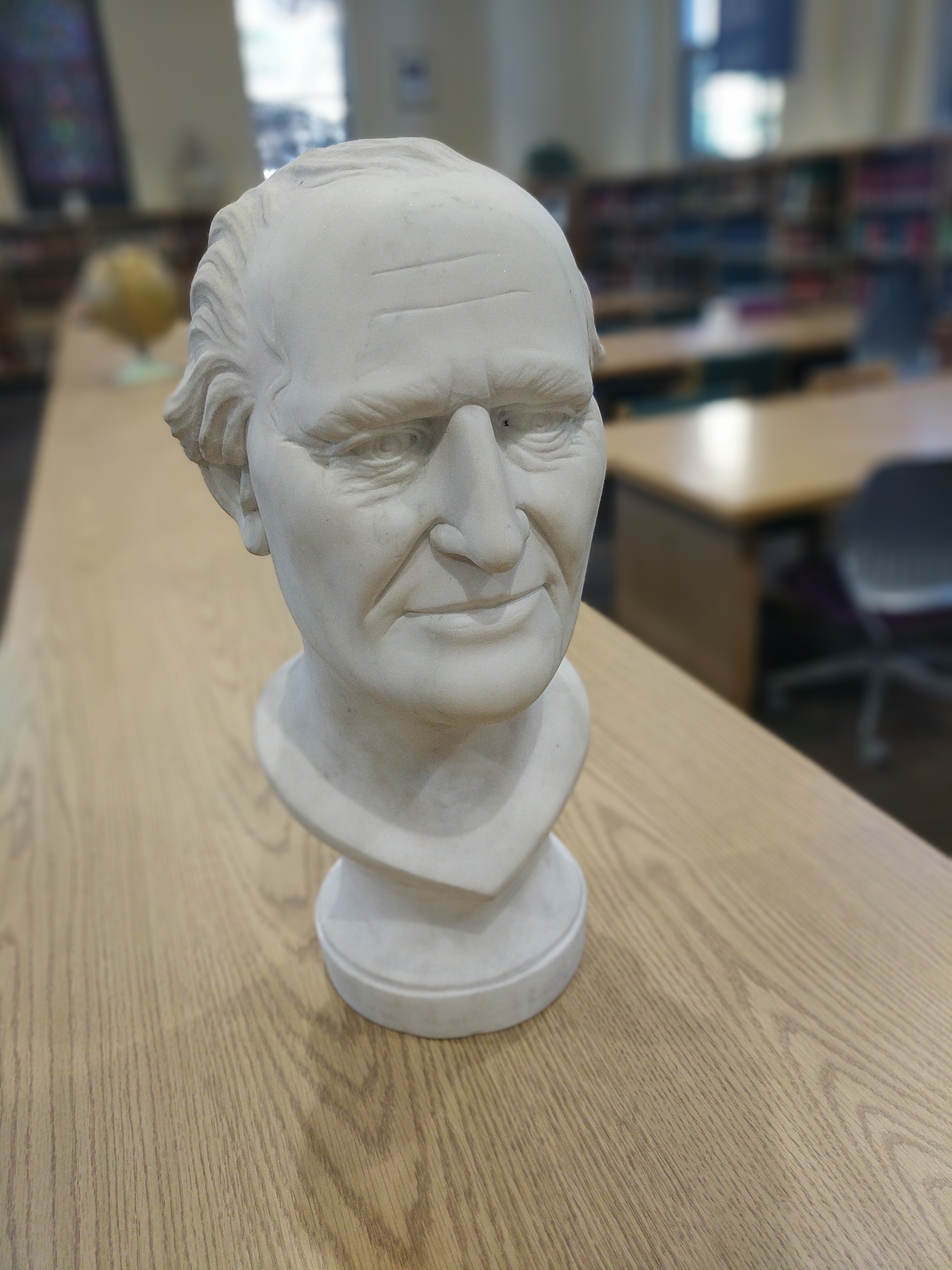

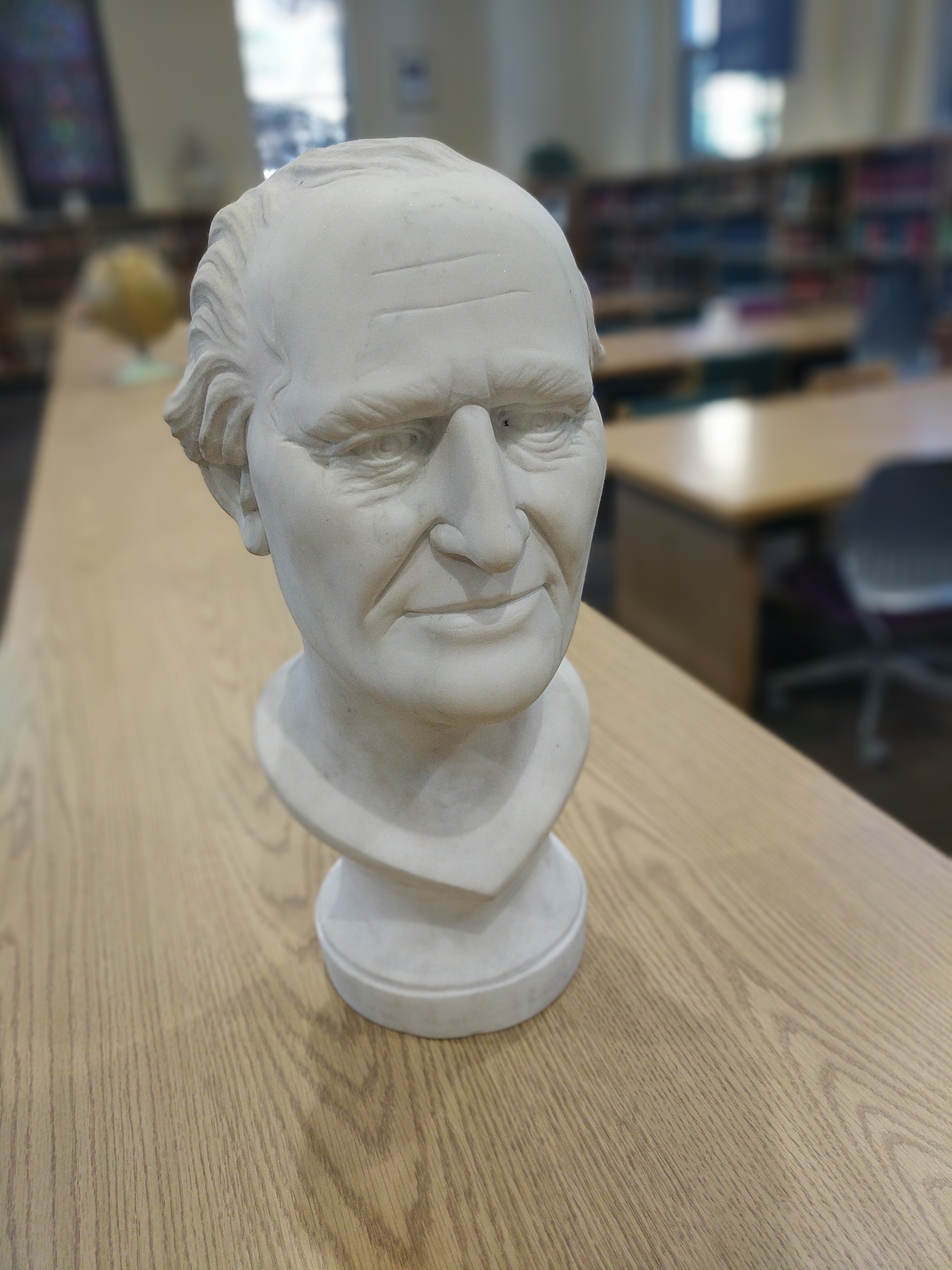

A friend of James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railway director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwest ...

, whose wife Mary was Catholic (even though Hill was not), Archbishop Ireland had his portrait painted in 1895 by the Swiss-born American portrait painter Adolfo Müller-Ury

Adolfo Müller-Ury, Order of St. Gregory the Great, KSG (March 29, 1862 – July 6, 1947) was a Swiss-born American portrait painter and Impressionism, impressionistic painter of roses and still life.

Early life and education

Müller was b ...

almost certainly on Hill's behalf, which was exhibited at M. Knoedler & Co., New York, January 1895 (lost) and again in 1897 (Archdiocesan Archives, Archdiocese of Saint Paul & Minneapolis).

Legacy

The influence of his personality made Archbishop Ireland a commanding figure in many important movements, especially those fortotal abstinence

Teetotalism is the practice of voluntarily abstinence, abstaining from the consumption of Alcohol (drug), alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler (US) or tee ...

, for colonization in the Northwest, and modern education. Ireland became a leading civic and religious leader during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Saint Paul. He worked closely with non-Catholics and was recognized by them as a leader of the Modernist Catholics.

Ireland called for racial equality at a time in the U.S. when the concept was considered extreme. On May 5, 1890, he gave a sermon at St. Augustine's Church, in Washington, D.C., the center of an African-American parish, to a congregation that included several public officials, Congressmen including the full Minnesota delegation, U.S. Treasury Secretary William Windom William Windom may refer to:

* William Windom (politician) (1827–1891), U.S. representative from Minnesota

* William Windom (actor) (1923–2012), his great-grandson, American actor

See also

* William Windham (disambiguation)

{{hndis, Wi ...

, and Blanche Bruce

Blanche Kelso Bruce (March 1, 1841March 17, 1898) was an American politician who represented Mississippi as a Republican in the United States Senate from 1875 to 1881. Born into slavery in Prince Edward County, Virginia, he went on to become ...

, the second black U.S. Senator. Ireland's sermon on racial justice concluded with the statement, "The color line must go; the line will be drawn at personal merit." It was reported that "the bold and outspoken stand of the Archbishop on this occasion created somewhat of a sensation throughout America."

Colonization

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and Bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

John Lancaster Spalding of the Diocese of Peoria, Illinois, founded the Irish Catholic Colonization Association. This organization bought land in rural areas to the west and south and helped resettle Irish Catholics from the urban slums.

Ireland helped establish many Irish Catholic colonies in Minnesota. The land had been cleared of its native Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin ( ; Dakota/ Lakota: ) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples (translati ...

following the Dakota War of 1862

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several eastern bands of Dakota people, Da ...

. He served as director of the National Colonization Association. From 1876 to 1881 Ireland organized and directed the most successful rural colonization program ever sponsored by the Catholic Church in the U.S. Working with the western railroads and with the Minnesota state government, he brought more than 4,000 Catholic families from the slums of eastern urban areas and settled them on more than of farmland in rural Minnesota.

His partner in Ireland was John Sweetman, a wealthy brewer who helped set up the Irish-American Colonisation Company there.

In 1880, Ireland assisted several hundred people from Connemara

Connemara ( ; ) is a region on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht, ...

in Ireland to emigrate to Minnesota. They arrived at the wrong time of the year and had to be assisted by local Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

s, an organisation that the Catholic Church condemns on many points. In the public debate that followed, the immigrants, being Connaught Irish

Connacht Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Connacht.

Gaeltacht regions in Connacht are found in Counties Mayo (notably Tourmakeady, Achill Island and Erris) and Galway (notably in parts of Connemara an ...

monoglot

Monoglottism (Greek μόνος ''monos'', "alone, solitary", + γλῶττα , "tongue, language") or, more commonly, monolingualism or unilingualism, is the condition of being able to speak only a single language, as opposed to multilingualism. ...

speakers, could not voice their opinions of Bishop Ireland's criticism of their acceptance of the Masons' support during a harsh winter. De Graff and Clontarf in Swift County, Adrian

Adrian is a form of the Latin given name Adrianus or Hadrianus. Its ultimate origin is most likely via the former river Adria from the Venetic and Illyrian word ''adur'', meaning "sea" or "water".

The Adria was until the 8th century BC the ma ...

in Nobles County, Avoca, Iona

Iona (; , sometimes simply ''Ì'') is an island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaeli ...

and Fulda

Fulda () (historically in English called Fuld) is a city in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district (''Kreis''). In 1990, the city hosted the 30th Hessentag state festival.

Histor ...

in Murray County, Graceville in Big Stone County and Ghent

Ghent ( ; ; historically known as ''Gaunt'' in English) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the Provinces of Belgium, province ...

in Lyon County were all colonies established by Ireland.

Charlotte Grace O'Brien, philanthropist and activist for the protection of female emigrants, found that often the illiterate young women were being tricked into prostitution through spurious offers of employment. She proposed an information bureau at Castle Garden

Castle Clinton (also known as Fort Clinton and Castle Garden) is a restored circular sandstone fort within Battery Park at the southern end of Manhattan in New York City, United States. Built from 1808 to 1811, it was the first American immig ...

, the disembarkation point for immigrants arriving in New York; a temporary shelter to provide accommodation for immigrants, and a chapel, all to Archbishop Ireland, who she believed of all the American hierarchy would be most sympathetic. Ireland agreed to raise the matter at the May 1883 meeting of the Irish Catholic Association which endorsed the plan and voted to establish an information bureau at Castle Garden. The Irish Catholic Colonization Association was also instrumental in the establishment of the Mission of Our Lady of the Rosary for the Protection of Irish Immigrant Girls.

Education

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to Vatican City

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

to defend it, and he succeeded in doing so. He also supported the English only movement

The English-only movement, also known as the Official English movement, is a political movement that advocates for the exclusive use of the English language in official United States government communication through the establishment of English ...

, which he sought to enforce within American Catholic churches and parochial school

A parochial school is a private school, private Primary school, primary or secondary school affiliated with a religious organization, and whose curriculum includes general religious education in addition to secular subjects, such as science, mathem ...

s. The continued use of heritage language

A heritage language is a minority language (either immigrant or indigenous) learned by its speakers at home as children, and difficult to be fully developed because of insufficient input from the social environment. The speakers grow up with a ...

s was not uncommon at the time because of the recent large influx of immigrants to the U.S. from European countries. Ireland influenced American society by actively demanding the immediate adoption of the English language by German-Americans

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

and other recent immigrants. He is the author of ''The Church and Modern Society'' (1897).

According his biographers Fr. Vincent A. Yzermans and Franz Xaver Wetzel, there is a great historical importance to the well documented clashes between Rt.-Rev. John Joseph Frederick Otto Zardetti

John Joseph Frederick Otto Zardetti (January 24, 1847 – May 10, 1902) was a Swiss prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He first served as the first bishop of the new Diocese of Saint Cloud in Minnesota in the United States from 1889 to 189 ...

while Bishop of St. Cloud, with Archbishop John Ireland and his supporters within the American hierarchy. These clashes were both over Zardetti's hostility to Archbishop Ireland's Modernist theology and Zardetti's belief that American patriotism

Americanism, also referred to as American patriotism, is a set of nationalist values which aim to create a collective ''American identity'' for the United States that can be defined as "an articulation of the nation's rightful place in the world ...

was compatible with teaching and nurturing the German language in the United States

Over 50 million Americans claim German ancestry, which made them the largest single claimed ancestry group in the United States until 2020. Around 1.06 million people in the United States speak the German language at home. It is the second m ...

and other heritage language

A heritage language is a minority language (either immigrant or indigenous) learned by its speakers at home as children, and difficult to be fully developed because of insufficient input from the social environment. The speakers grow up with a ...

s like it. Zardetti later played a major role, as an official of the Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

, in pushing for the Apostolic letter '' Testem Benevolentiae'', which was signed by Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

on 22 January 1899. As a reward, Zardetti was promoted to assistant to the papal throne

The Bishops-Assistant at the Pontifical Throne were ecclesiastical titles in the Catholic Church. It designated prelates belonging to the Papal Chapel, who stood near the throne of the Pope at solemn functions. They ranked immediately below the ...

on 14 February 1899. In commenting on Zardetti's role in the letter, Fr. Yzermans has commented, "In this arena he might well have had seen his greatest impact on American Catholicism in the first half of the twentieth century in the United States."

Relations with Eastern Catholics

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical credential

A credential is a piece of any document that details a qualification, competence, or authority issued to an individual by a third party with a relevant or ''de facto'' authority or assumed competence to do so.

Examples of credentials include aca ...

s of Byzantine Rite

The Byzantine Rite, also known as the Greek Rite or the Rite of Constantinople, is a liturgical rite that is identified with the wide range of cultural, devotional, and canonical practices that developed in the Eastern Christianity, Eastern Chri ...

, Ruthenian Catholic

The Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church, also known in the United States as the Byzantine Catholic Church, is a ''sui iuris'' (autonomous) Eastern Catholic particular church based in Eastern Europe and North America that is part of the worldwide ...

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

Alexis Toth

Alexis Georgievich Toth (also Alexis of Wilkes-Barre; March 14, 1853 – May 7, 1909) was a Russian Orthodox church leader in the Midwestern United States who, having resigned his position as a Byzantine Catholic priest in the Ruthenian Catho ...

, despite Toth's being a widower. Ireland then forbade Toth to minister to his own parishioners. Ireland was also involved in efforts to expel all non-Latin Church Catholic clergy from the United States. Forced into an impasse, Toth went on to lead thousands of Ruthenian Catholics out of the Roman Communion and into what would eventually become the Orthodox Church in America

The Orthodox Church in America (OCA) is an Eastern Orthodox Christian church based in North America. The OCA consists of more than 700 parishes, missions, communities, monasteries and institutions in the United States, Canada and Mexico. In ...

. Because of this, Archbishop Ireland is sometimes referred to, ironically, as "The Father of the Orthodox Church in America". Marvin R. O'Connell, author of a biography of Ireland, summarizes the situation by stating that "if Ireland's advocacy of the blacks displayed him at his best, his belligerence toward the Uniates showed him at his bull-headed worst."

Establishments

At the

At the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore

The Plenary Councils of Baltimore were three meetings of American Catholic bishops, archbishops and superiors of religious orders in the United States. The councils were held in 1852, 1866 and 1884 in Baltimore, Maryland.

These three conferenc ...

, the establishment of a Catholic university was decided. In 1885, Ireland was appointed to a committee, along with, Bishop John Lancaster Spalding, Cardinal James Gibbons

James Cardinal Gibbons (July 23, 1834 – March 24, 1921) was an American Catholic prelate who served as Apostolic Vicar of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, Bishop of Richmond from 1872 to 1877, and as Archbishop of Baltimore from 1877 unti ...

and then bishop John Joseph Keane dedicated to developing and establishing The Catholic University of America

The Catholic University of America (CUA) is a private Catholic research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is one of two pontifical universities of the Catholic Church in the United States – the only one that is not primarily ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

Ireland retained an active interest in the university for the rest of his life.

He founded Saint Thomas Aquinas Seminary, progenitor of four institutions: University of Saint Thomas (Minnesota)

The University of St. Thomas (also known as UST or simply St. Thomas) is a private Catholic research university with campuses in Saint Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. Founded in 1885 as a Catholic seminary, it is named after Thom ...

, the Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity

The Saint Paul Seminary (SPS) is a Catholic major seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. A part of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, SPS prepares men to enter the priesthood and permanent diaconate, and educates lay men and women on Ca ...

, Nazareth Hall Preparatory Seminary

Nazareth Hall Preparatory Seminary, known familiarly as Naz Hall, was a Minor seminary, high school seminary in Arden Hills, Minnesota, United States, serving the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, Archdiocese of Saint Pa ...

, and Saint Thomas Academy

Saint Thomas Academy (abbr. STA), originally known as St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary and formerly known as St. Thomas Military Academy, is an all-male, Catholic military high school in Mendota Heights, Minnesota. The academy has a middle school (gr ...

. The Saint Paul Seminary

The Saint Paul Seminary (SPS) is a Catholic Church, Catholic major seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. A part of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, SPS prepares men to enter th ...

was established with the help of Methodist James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railway director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwest ...

, whose wife, Mary Mehegan, was a devout Catholic.Empson, ''The Streets Where You Live'', 143 Both institutions are located on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. DeLaSalle High School

DeLaSalle High School ( ) is a Catholic, college preparatory high school in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It is located on Nicollet Island.

History

DeLaSalle opened in 1900 and has been administered by the De La Salle Brothers (French Christian Brot ...

located on Nicollet Island

Nicollet Island ( ) is an island in the Mississippi River just north of Saint Anthony Falls in central Minneapolis, Minnesota. According to the United States Census Bureau the island has a land area of and a 2000 census population of 144 person ...

in Minneapolis was opened in October 1900 through a gift of $25,000 from Ireland. Fourteen years later Ireland purchased an adjacent property for the expanding Christian Brothers school.

In 1904, Ireland secured the land for the building of the current Cathedral of Saint Paul located atop Summit Hill, the highest point in downtown Saint Paul. At the same time, on Christmas Day 1903, he also commissioned the construction of the almost equally large Church of Saint Mary, for the Immaculate Conception parish in the neighboring city of Minneapolis. It became the Pro-Cathedral of Minneapolis and later became the Basilica of Saint Mary, the first basilica in the United States in 1926. Both were designed and built under the direction of the French architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray

Emmanuel Louis Masqueray (1861–1917) was a Franco-American preeminent figure in the history of American architecture, both as a gifted designer of landmark buildings and as an influential teacher of the profession of architecture dedicated t ...

.

John Ireland Boulevard, a Saint Paul street that runs from the Cathedral of Saint Paul northeast to the Minnesota State Capitol

The Minnesota State Capitol is the seat of government for the U.S. state of Minnesota, in its capital (political), capital city of Saint Paul, Minnesota, Saint Paul. It houses the Minnesota Senate, Minnesota House of Representatives, the offic ...

, is named in his honor. It was so named in 1961 at the encouragement of the Ancient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is in the United States, where it was founded in New Yo ...

.

References

Further reading

* *Brunk, Timothy. “American Exceptionalism in the Thought of John Ireland.” American Catholic Studies 119, no. 1 (2008): 43–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44195141. *Dordevic, Mihailo. “Archbishop Ireland and the Church-State Controversy in France in 1892.” Minnesota History 42, no. 2 (1970): 63–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20178085. * Farrell, John T. “Archbishop Ireland and Manifest Destiny.” The Catholic Historical Review 33, no. 3 (1947): 269–301. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25014801. * * . Pages 143–144 * *Moynihan, James H. “The Pastoral Message of Archbishop Ireland.” The Furrow 3, no. 12 (1952): 639–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27656120. *O’Neill, Daniel P. “The Development of an American Priesthood: Archbishop John Ireland and the Saint Paul Diocesan Clergy, 1884-1918.” Journal of American Ethnic History 4, no. 2 (1985): 33–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27500378. * *Rippley, La Vern J. “Archbishop Ireland and the School Language Controversy.” U.S. Catholic Historian 1, no. 1 (1980): 1–16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25153638. *Shannon, James P. “Archbishop Ireland’s Experiences as a Civil War Chaplain.” The Catholic Historical Review 39, no. 3 (1953): 298–305. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25015610. *Storch, Neil T. “John Ireland’s Americanism after 1899: The Argument from History.” Church History 51, no. 4 (1982): 434–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/3166194. *Storch, Neil T. “John Ireland and the Modernist Controversy.” Church History 54, no. 3 (1985): 353–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/3165660. *Wangler, Thomas E. “John Ireland and the Origins of Liberal Catholicism in the United States.” The Catholic Historical Review 56, no. 4 (1971): 617–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25018691.External links

* *Bio

MNopedia. *

Bishop Ireland's Connemara Experiment:

''

Minnesota Historical Society

The Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit Educational institution, educational and cultural institution dedicated to preserving the history of the U.S. state of Minnesota. It was founded by the Minnesota Terr ...

''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ireland, John

1838 births

1918 deaths

History of Saint Paul, Minnesota

Irish emigrants to the United States

Catholic Church and minority language rights

Christian clergy from County Kilkenny

Roman Catholic bishops of Saint Paul

Roman Catholic archbishops of Saint Paul

19th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the United States

20th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the United States

Union army chaplains

19th-century Irish people

University of St. Thomas (Minnesota)

Catholic military chaplains