John C. Breckinridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American politician who served as the 14th

A supporter of the Mexican–American War, Breckinridge sought appointment to the staff of Major General William Orlando Butler, a prominent Kentucky Democrat, but Butler could only offer him an unpaid aide position and advised him to decline it. In July 1847, Breckinridge delivered an address at a mass military funeral in Frankfort to honor Kentuckians killed in the Battle of Buena Vista. The oration brought Whig Senator

A supporter of the Mexican–American War, Breckinridge sought appointment to the staff of Major General William Orlando Butler, a prominent Kentucky Democrat, but Butler could only offer him an unpaid aide position and advised him to decline it. In July 1847, Breckinridge delivered an address at a mass military funeral in Frankfort to honor Kentuckians killed in the Battle of Buena Vista. The oration brought Whig Senator

Breckinridge received 1,481 votes, over 400 more than his nearest competitor, making this the first time that Fayette County had elected a Democrat to the state House of Representatives. Between the election and the legislative session, Breckinridge formed a new law partnership with Owsley's former secretary of state, George B. Kinkead, his previous partner having died in a

Breckinridge received 1,481 votes, over 400 more than his nearest competitor, making this the first time that Fayette County had elected a Democrat to the state House of Representatives. Between the election and the legislative session, Breckinridge formed a new law partnership with Owsley's former secretary of state, George B. Kinkead, his previous partner having died in a

The Whigs, seeking to recapture Breckinridge's seat, nominated Attorney General of Kentucky James Harlan, but some Whig factions opposed him, and he withdrew in March. Robert P. Letcher, a former congressman and governor who had won 14 elections in Kentucky without a loss, was the party's second choice. Both candidates campaigned vigorously throughout the Eighth District, making multiple speeches a day between May and August. Letcher was an experienced campaigner, but his popular, anecdote-filled oratory was unpolished, and he was prone to outbursts of anger when frustrated. By contrast, Breckinridge delivered calm, well-reasoned speeches. Cassius Clay, a political enemy of Letcher's for years, endorsed Breckinridge, despite their differences on slavery. Citing this endorsement and the abolitionism of Breckinridge's uncles, Letcher tried to paint Breckinridge as an enemy of slavery. Breckinridge pointed to his consistent support for slavery and claimed Letcher was actually hostile to the interests of slaveholders. Although the district had gone for Whig candidate Winfield Scott by over 600 votes in the previous year's presidential election, Breckinridge defeated Letcher by 526 votes. Once again, he received a large margin in Owen County, which reported 123 more votes than eligible voters living in the county. Grateful for the support of the reliably Democratic county, he gave his son John Witherspoon Breckinridge the nickname "Owen".

Of the 234 members of the House, Breckinridge was among the 80 who were returned to their seats for the Thirty-third Congress. Due to his increased seniority, he was assigned to the more prestigious

The Whigs, seeking to recapture Breckinridge's seat, nominated Attorney General of Kentucky James Harlan, but some Whig factions opposed him, and he withdrew in March. Robert P. Letcher, a former congressman and governor who had won 14 elections in Kentucky without a loss, was the party's second choice. Both candidates campaigned vigorously throughout the Eighth District, making multiple speeches a day between May and August. Letcher was an experienced campaigner, but his popular, anecdote-filled oratory was unpolished, and he was prone to outbursts of anger when frustrated. By contrast, Breckinridge delivered calm, well-reasoned speeches. Cassius Clay, a political enemy of Letcher's for years, endorsed Breckinridge, despite their differences on slavery. Citing this endorsement and the abolitionism of Breckinridge's uncles, Letcher tried to paint Breckinridge as an enemy of slavery. Breckinridge pointed to his consistent support for slavery and claimed Letcher was actually hostile to the interests of slaveholders. Although the district had gone for Whig candidate Winfield Scott by over 600 votes in the previous year's presidential election, Breckinridge defeated Letcher by 526 votes. Once again, he received a large margin in Owen County, which reported 123 more votes than eligible voters living in the county. Grateful for the support of the reliably Democratic county, he gave his son John Witherspoon Breckinridge the nickname "Owen".

Of the 234 members of the House, Breckinridge was among the 80 who were returned to their seats for the Thirty-third Congress. Due to his increased seniority, he was assigned to the more prestigious

In February 1854, the Whig majority in the Kentucky General Assembly passed – over Powell's veto – a reapportionment bill that redrew Breckinridge's district, removing Owen County and replacing it with Harrison and

In February 1854, the Whig majority in the Kentucky General Assembly passed – over Powell's veto – a reapportionment bill that redrew Breckinridge's district, removing Owen County and replacing it with Harrison and

Buchanan rarely consulted Breckinridge when making patronage appointments, and meetings between the two were infrequent. When Buchanan and Breckinridge endorsed the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state instead of allowing the people to vote, they managed to alienate most Northern Democrats, including Douglas. This disagreement ended plans for Breckinridge, Douglas, and Minnesota's Henry Mower Rice to build a series of three elaborate, conjoined

Buchanan rarely consulted Breckinridge when making patronage appointments, and meetings between the two were infrequent. When Buchanan and Breckinridge endorsed the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state instead of allowing the people to vote, they managed to alienate most Northern Democrats, including Douglas. This disagreement ended plans for Breckinridge, Douglas, and Minnesota's Henry Mower Rice to build a series of three elaborate, conjoined

In the four-way contest, Breckinridge came in third in the popular vote, with 18.1%, but second in the Electoral College. The final electoral vote was 180 for Lincoln, 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell, and 12 for Douglas. Although Breckinridge won the states of the

In the four-way contest, Breckinridge came in third in the popular vote, with 18.1%, but second in the Electoral College. The final electoral vote was 180 for Lincoln, 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell, and 12 for Douglas. Although Breckinridge won the states of the

Breckinridge's performance earned him a promotion to major general on April 14, 1862. After his promotion, he joined Earl Van Dorn near Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Confederate forces awaited a Union attack throughout most of July. Finally, Van Dorn ordered Breckinridge to attempt to recapture

Breckinridge's performance earned him a promotion to major general on April 14, 1862. After his promotion, he joined Earl Van Dorn near Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Confederate forces awaited a Union attack throughout most of July. Finally, Van Dorn ordered Breckinridge to attempt to recapture

By late February, Breckinridge concluded that the Confederate cause was hopeless. Delegating the day-to-day operations of his office to his assistant, John Archibald Campbell, he began laying the groundwork for surrender. Davis desired to continue the fight, but Breckinridge urged, "This has been a magnificent epic. In God's name let it not terminate in farce." On April 2, Lee sent a telegram to Breckinridge informing him that he would have to withdraw from his position that night, and that this would necessitate the evacuation of Richmond. Ordering Campbell to organize the flight of the Confederate cabinet to

By late February, Breckinridge concluded that the Confederate cause was hopeless. Delegating the day-to-day operations of his office to his assistant, John Archibald Campbell, he began laying the groundwork for surrender. Davis desired to continue the fight, but Breckinridge urged, "This has been a magnificent epic. In God's name let it not terminate in farce." On April 2, Lee sent a telegram to Breckinridge informing him that he would have to withdraw from his position that night, and that this would necessitate the evacuation of Richmond. Ordering Campbell to organize the flight of the Confederate cabinet to

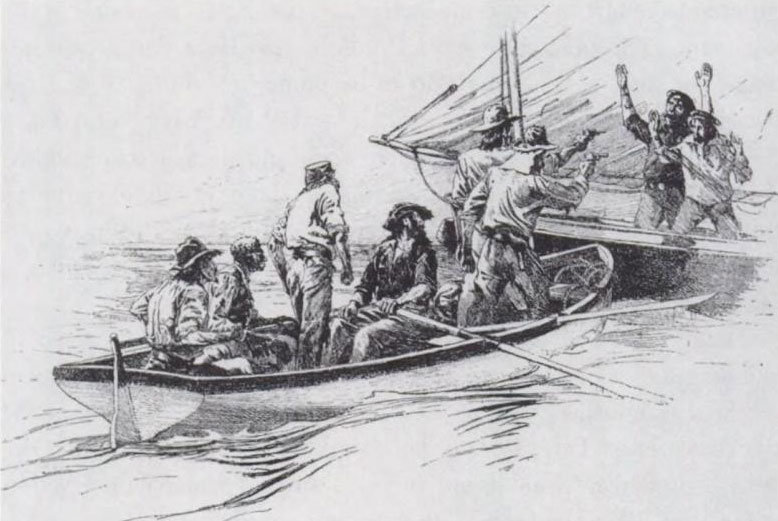

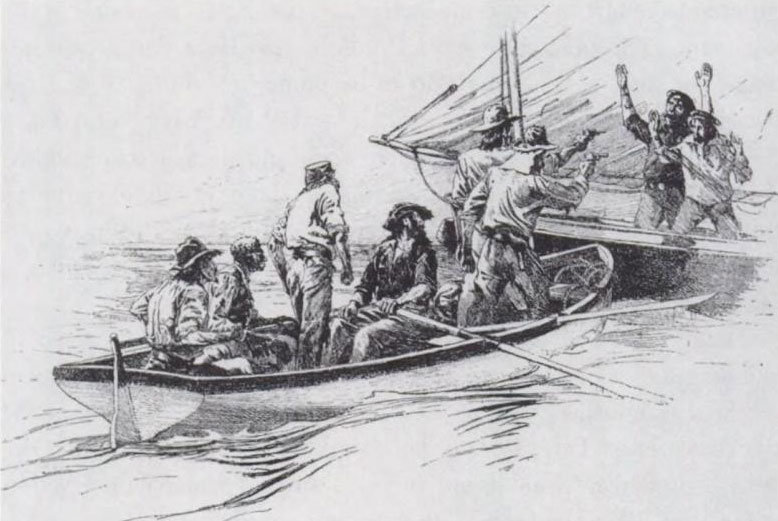

At

At

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

, with President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, from 1857 to 1861. Assuming office at the age of 36, Breckinridge is the youngest vice president in U.S. history. Breckinridge was also the Southern Democratic candidate in the 1860 presidential election, which he lost to Republican Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

.

Breckinridge was born near Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the List of ...

, to a prominent local family. After serving as a noncombatant during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, he was elected as a Democrat to the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

in 1849, where he took a pro-slavery stance. Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1851, he allied with Stephen A. Douglas in support of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. After reapportionment in 1854 made his re-election unlikely, he declined to run for another term. He was nominated for vice president at the 1856 Democratic National Convention to balance a ticket headed by James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

. The Democrats won the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

, but Breckinridge had little influence with Buchanan, and as presiding officer of the Senate, could not express his opinions in debates. He joined Buchanan in supporting the proslavery Lecompton Constitution for Kansas, which led to a split in the Democratic Party. In 1859, he was elected to succeed Senator John J. Crittenden at the end of Crittenden's term in 1861.

After Southern Democrats walked out of the 1860 Democratic National Convention, the party's northern and southern factions held rival conventions in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

that nominated Douglas and Breckinridge, respectively, for president. A third party, the Constitutional Union Party, nominated John Bell. These three men split the Southern vote, while antislavery Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

won all but three electoral votes in the North, winning the election. Breckinridge carried most of the Southern states. Taking his seat in the Senate, Breckinridge urged compromise to preserve the Union. Unionists were in control of the state legislature, and gained more support when Confederate forces moved into Kentucky. Breckinridge fled behind Confederate lines. He was commissioned a brigadier general and then expelled from the Senate.

Following the Battle of Shiloh in 1862, Breckinridge was promoted to major general, and in October, he was assigned to the Army of Mississippi under Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army Officer (armed forces), officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate General officers in the Confederate States Army, general in th ...

. After Bragg charged that Breckinridge's drunkenness had contributed to defeats at Stones River and Missionary Ridge, and after Breckinridge joined many other high-ranking officers in criticizing Bragg, he was transferred to the Trans-Allegheny Department, where he won his most significant victory in the 1864 Battle of New Market. After participating in Jubal Early's campaigns in the Shenandoah Valley, Breckinridge was charged with defending supplies in Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. In February 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

appointed him secretary of war. Concluding that the war was hopeless, he urged Davis to arrange a national surrender. After the fall of Richmond, Breckinridge ensured the preservation of Confederate records. He then escaped the country and lived abroad for over three years. When President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

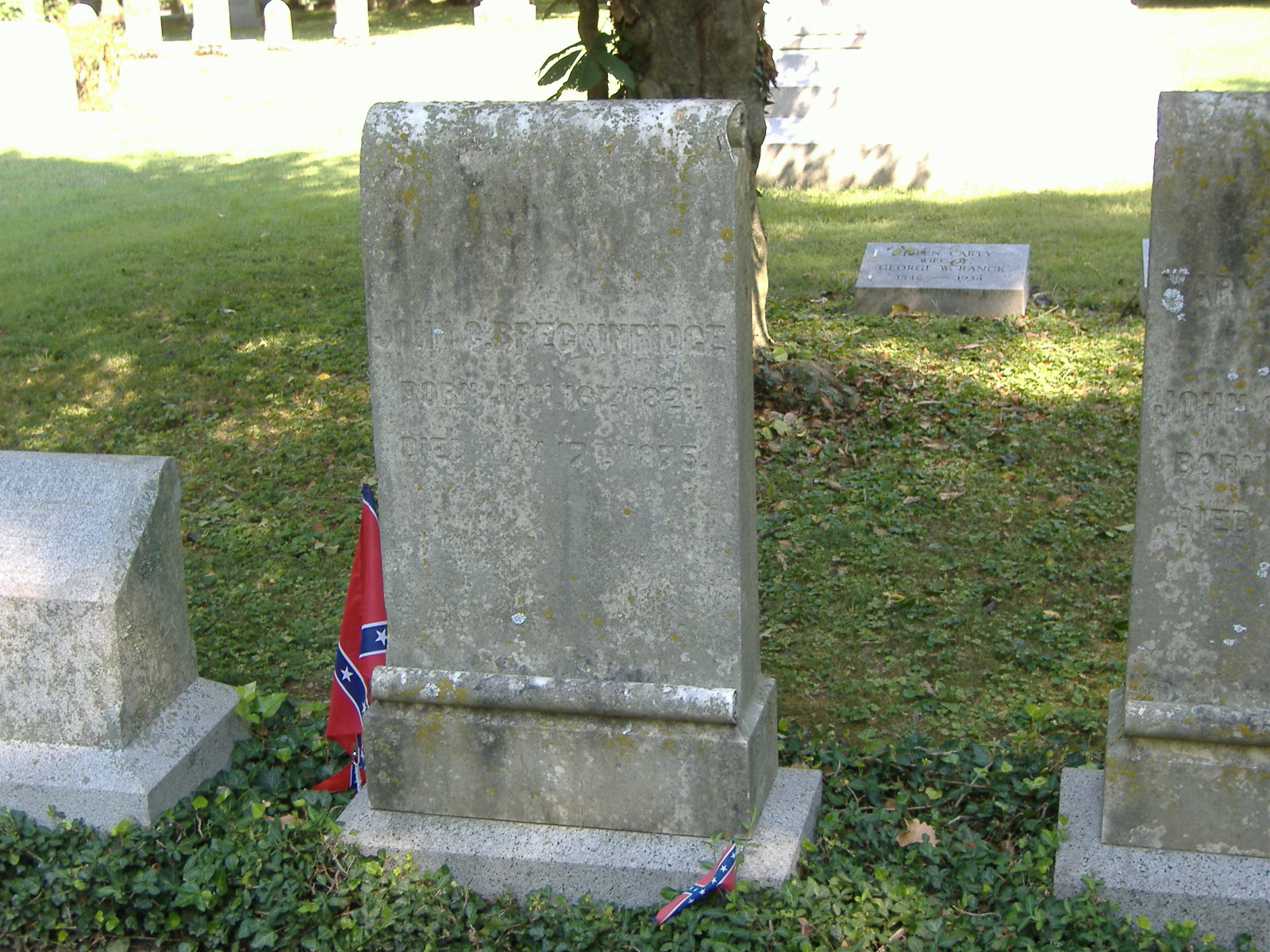

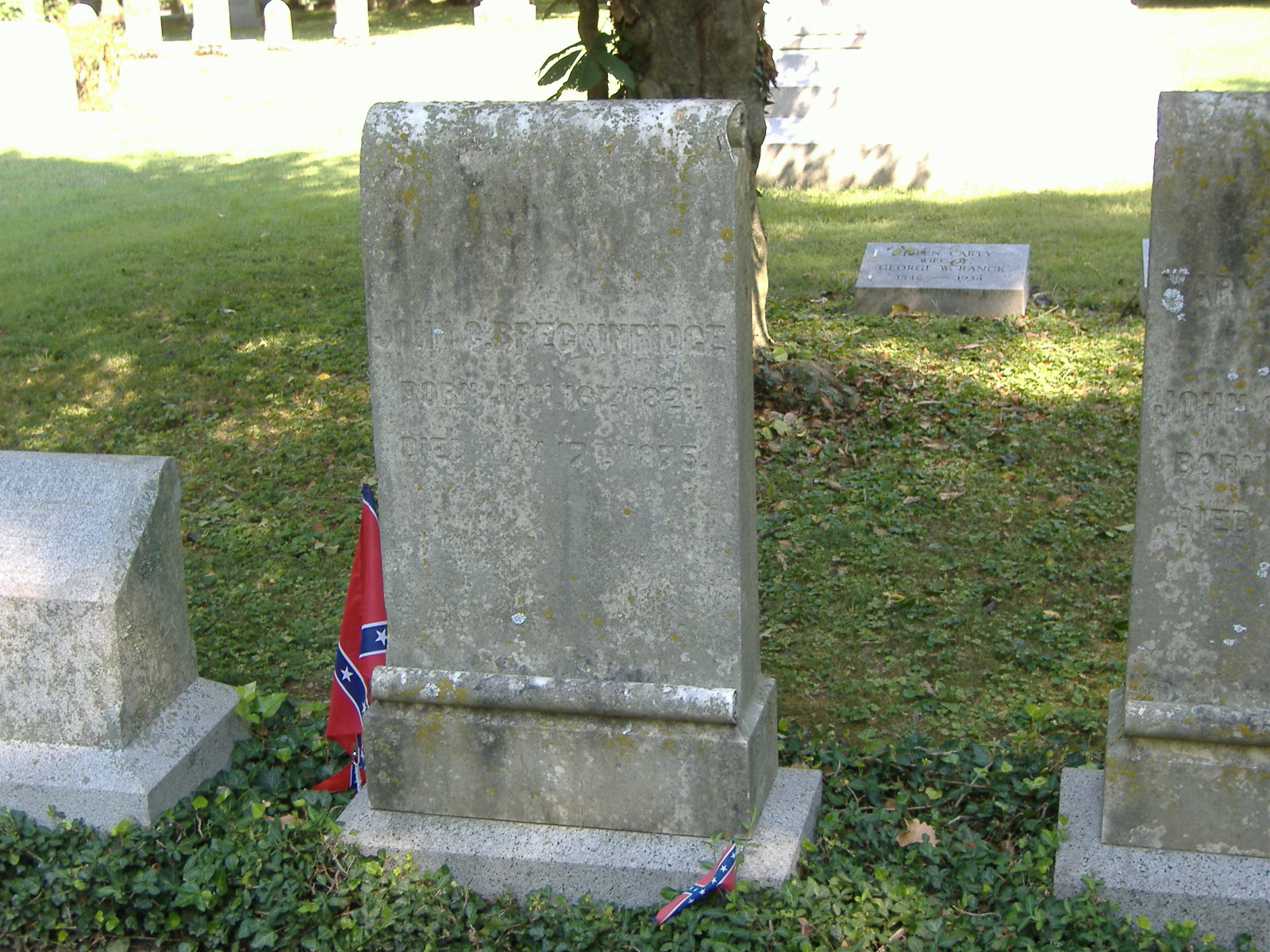

extended amnesty to all former Confederates in 1868, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky, but resisted all encouragement to resume his political career. War injuries sapped his health, and he died in 1875. Breckinridge is regarded as an effective military commander, but historians have panned his contributions to the Confederacy, and Breckinridge has been labeled as both a traitor and consistently ranked as one of the nation's worst vice presidents.

Early life

John Cabell Breckinridge was born at Thorn Hill, his family's estate near Lexington, Kentucky, on January 16, 1821, the fourth of six children and only son of Joseph "Cabell" Breckinridge and Mary Clay (Smith) Breckinridge. His mother was the daughter of Samuel Stanhope Smith, who foundedHampden–Sydney College

Hampden–Sydney College (H-SC) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Men's colleges in the United States, college for men in Hampden Sydney, Virginia. Founded in 1775, it is the oldest privatel ...

in 1775, and granddaughter of John Witherspoon, a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

. Having previously served as speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives, Breckinridge's father had been appointed Kentucky's secretary of state just prior to his son's birth. In February, one month after Breckinridge's birth, the family moved with Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

John Adair

John Adair (January 9, 1757 – May 19, 1840) was an American pioneer, slave trader, soldier, and politician. He was the List of Governors of Kentucky, eighth Governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both the United States House of Re ...

to the Governor's Mansion in Frankfort, so his father could better attend to his duties as secretary of state.

In August 1823, an illness referred to as "the prevailing fever" struck Frankfort, and Cabell Breckinridge took his children to stay with his mother in Lexington. On his return, both his wife and he fell ill. Cabell Breckinridge died, but she survived. His assets were not enough to pay his debts, and his widow joined the children in Lexington, supported by her mother-in-law. While in Lexington, Breckinridge attended Pisgah Academy in Woodford County. His grandmother taught him the political philosophies of her late husband, John Breckinridge, who served in the U.S. Senate and as attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

under President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

. As a state legislator, Breckinridge had introduced the Kentucky Resolutions in 1798, which stressed states' rights and endorsed the doctrine of nullification in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were a set of four United States statutes that sought, on national security grounds, to restrict immigration and limit 1st Amendment protections for freedom of speech. They were endorsed by the Federalist Par ...

.

After an argument between Breckinridge's mother and grandmother in 1832, his mother, his sister Laetitia, and he moved to Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city and the county seat of Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 17,236 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micr ...

, to live with his sister Frances and her husband, John C. Young, who was president of Centre College

Centre College, formally Centre College of Kentucky, is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, United States. Chartered by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1819, the col ...

. Breckinridge's uncle, William Breckinridge, was also on the faculty there, prompting him to enroll in November 1834. Among his schoolmates were Beriah Magoffin, William Birney, Theodore O'Hara, Thomas L. Crittenden, and Jeremiah Boyle. After earning a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

in September 1838, he spent the following winter as a "resident graduate" at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Returning to Kentucky in mid-1839, he read law with Judge William Owsley. In November 1840, he enrolled in the second year of the law course at Transylvania University in Lexington, where his instructors included George Robertson and Thomas A. Marshall of the Kentucky Court of Appeals. On February 25, 1841, he received a Bachelor of Laws

A Bachelor of Laws (; LLB) is an undergraduate law degree offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree and serves as the first professional qualification for legal practitioners. This degree requires the study of core legal subje ...

and was licensed to practice the next day.

Early legal career

Breckinridge remained in Lexington while deciding where to begin practice, borrowing law books from the library of John J. Crittenden, Thomas Crittenden's father. Deciding that Lexington was overcrowded with lawyers, he moved to Frankfort, but was unable to find an office. After being spurned by a love interest, former classmate Thomas W. Bullock and he departed for the Iowa Territory on October 10, 1841, seeking better opportunities. They considered settling on land Breckinridge had inherited inJacksonville, Illinois

Jacksonville is a city and the county seat of Morgan County, Illinois, United States. The population was 17,616 at the 2020 census, down from 19,446 in 2010. It is home to Illinois College, Illinois School for the Deaf, and the Illinois Sc ...

, but they found the bar stocked with able men such as Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

. They continued on to Burlington, Iowa

Burlington is a city in, and the county seat of, Des Moines County, Iowa, United States. The population was 23,982 in the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, a decline from the 26,839 population in 2000 United States Census, 2000. Burlington ...

, and by the winter of 1842–1843, Breckinridge reported to family members that his firm handled more cases than almost any other in Burlington. Influenced by Bullock and the citizens of Iowa, he identified with the Democratic Party, and by February 1843, he had been named to the Democratic committee of Des Moines County. Most of the Kentucky Breckinridges were Whigs, and when he learned of his nephew's party affiliation, William Breckinridge declared, "I felt as I would have done if I had heard that my daughter had been dishonored."

Breckinridge visited Kentucky in May 1843. His efforts to mediate between his mother and the Breckinridges extended his visit, and after he contracted influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

, he decided to remain for the summer rather than returning to Iowa's colder climate. He met Bullock's cousin, Mary Cyrene Burch, and by September, they were engaged. In October, Breckinridge went to Iowa to close out his business, then returned to Kentucky and formed a law partnership with Samuel Bullock, Thomas's cousin. He married on December 12, 1843, and settled in Georgetown, Kentucky

Georgetown is a home rule-class city in Scott County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 37,086 at the 2020 census. It is the sixth-most populous city in Kentucky. It is the seat of its county. It was originally called Lebanon whe ...

. The couple had six children – Joseph Cabell (b. 1844), Clifton Rodes (b. 1846; later a Congressman from Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

), Frances (b. 1848), John Milton (b. 1849), John Witherspoon (b. 1850), and Mary Desha (b. 1854). Gaining confidence in his ability as a lawyer, Breckinridge moved his family back to Lexington in 1845 and formed a partnership with future U.S. Senator James B. Beck.

Mexican–American War

A supporter of the Mexican–American War, Breckinridge sought appointment to the staff of Major General William Orlando Butler, a prominent Kentucky Democrat, but Butler could only offer him an unpaid aide position and advised him to decline it. In July 1847, Breckinridge delivered an address at a mass military funeral in Frankfort to honor Kentuckians killed in the Battle of Buena Vista. The oration brought Whig Senator

A supporter of the Mexican–American War, Breckinridge sought appointment to the staff of Major General William Orlando Butler, a prominent Kentucky Democrat, but Butler could only offer him an unpaid aide position and advised him to decline it. In July 1847, Breckinridge delivered an address at a mass military funeral in Frankfort to honor Kentuckians killed in the Battle of Buena Vista. The oration brought Whig Senator Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

of Kentucky, whose son was among the dead, to tears, and inspired Theodore O'Hara to write " Bivouac of the Dead".

Breckinridge again applied for a military commission after William Owsley, the governor of Kentucky, called for two additional regiments on August 31, 1847. Owsley's advisors encouraged the Whig governor to commission at least one Democrat, and Whig Senator John J. Crittenden supported Breckinridge's application. On September 6, 1847, Owsley appointed Manlius V. Thomson as colonel, Thomas Crittenden as lieutenant colonel, and Breckinridge as major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

of the Third Kentucky Infantry Regiment. The regiment left Kentucky on November 1 and reached Vera Cruz by November 21. After a serious epidemic of ''la Vomito,'' or yellow fever, broke out at Vera Cruz, the regiment hurried to Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

. Reports indicate that Breckinridge walked all but two days of the journey, allowing weary soldiers to use his horse. When they reached Mexico City on December 18, the fighting was almost over; they participated in no combat and remained as an army of occupation until May 30, 1848.

In demand more for his legal expertise than his military training, he was named as assistant counsel for Gideon Johnson Pillow during a court of inquiry initiated against him by Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

. Seeking to derail Scott's presidential ambitions, Pillow and his supporters composed and published letters that lauded Pillow, not Scott, for the American victories at Contreras and Churubusco. To hide his involvement, Pillow convinced a subordinate to take credit for the letter he wrote. Breckinridge biographer William C. Davis writes that it was "most unlikely" that Breckinridge knew the details of Pillow's intrigue. His role in the proceedings was limited to questioning a few witnesses; records show that Pillow represented himself during the court's proceedings.

Returning to Louisville on July 16, the Third Kentucky mustered out on July 21. During their time in Mexico, over 100 members of the 1,000-man regiment died of illness. Although he saw no combat, Breckinridge's military service proved an asset to his political prospects.

Political career

Early political career

Breckinridge campaigned for Democratic presidential nominee James K. Polk in the 1844 election. He decided against running for county clerk of Scott County after his law partner complained that he spent too much time in politics. In 1845, some local Democrats encouraged him to seek the Eighth District's congressional seat, but he declined, supporting Alexander Keith Marshall, the party's unsuccessful nominee. As a private citizen, he opposed the Wilmot Proviso that would have banned slavery in the territory acquired in the war with Mexico. In the 1848 presidential election, he backed the unsuccessful Democratic ticket ofLewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

and William Butler. He did not vote in the election. Defending his decision during a speech in Lexington on September 5, 1860, Breckinridge explained:

Kentucky House of Representatives

In August 1849, Kentuckians elected delegates to a state constitutional convention in addition to state representatives and senators. Breckinridge'sabolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

uncles, William and Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, prais ...

, joined with Cassius Marcellus Clay

Major general (United States), Major General Cassius Marcellus Clay (October 9, 1810 – July 22, 1903) was an American planter, politician, military officer and abolitionist who served as the List of ambassadors of the United States to Russia, ...

to nominate slates of like-minded candidates for the constitutional convention and the legislature. In response, a bipartisan group of proslavery citizens organized its own slate of candidates, including Breckinridge for one of Fayette County's two seats in the House of Representatives. Breckinridge, who by this time enslaved five humans, had publicly opposed "impairing in any form" the legal protection of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. Despite his endorsement of slavery protections, he was a member of the Freemasons and the First Presbyterian Church in Lexington, both of which officially opposed slavery. He had also previously represented free blacks in court, expressed support for voluntary emancipation, and supported the Kentucky Colonization Society, which was dedicated to the relocation of free blacks to Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

.

Breckinridge received 1,481 votes, over 400 more than his nearest competitor, making this the first time that Fayette County had elected a Democrat to the state House of Representatives. Between the election and the legislative session, Breckinridge formed a new law partnership with Owsley's former secretary of state, George B. Kinkead, his previous partner having died in a

Breckinridge received 1,481 votes, over 400 more than his nearest competitor, making this the first time that Fayette County had elected a Democrat to the state House of Representatives. Between the election and the legislative session, Breckinridge formed a new law partnership with Owsley's former secretary of state, George B. Kinkead, his previous partner having died in a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic earlier in the year. He also co-founded the ''Kentucky Statesman'', a semiweekly Democratic newspaper, and visited his step-cousin, Mary Todd, where he met her husband, Abraham Lincoln, for the first time; despite their political differences, they became friends.

When the House convened, Breckinridge received a plurality of votes for speaker, but fell at least eight votes short of a majority. Unable to break the deadlock, he withdrew, and the position went to Whig Thomas Reilly. Biographer Frank H. Heck wrote that Breckinridge was the leader of the House Democratic caucus during the session, during which time most of the measures considered were "local or personal and in any case, petty". Breckinridge was assigned to the House's standing committees on federal relations and the judiciary. He supported bills allocating funding for internal improvements, a traditionally Whig stance. As Congress debated Henry Clay's proposed Compromise of 1850, the four Whigs on the Committee on Federal Relations drew up resolutions urging the Kentucky congressional delegation to support the compromise as a "fair, equitable, and just basis" for settlement of the slavery issue in the newly acquired U.S. territories. Breckinridge felt that the resolution was too vague and authored a minority report that explicitly denied federal authority to interfere with slavery in states and territories. Both sets of resolutions, and a set adopted by the Senate, were all laid on the table.

On March 4, 1850, three days before the end of the session, Breckinridge took a leave of absence to care for his son, John Milton, who had become ill; he died on March 18. Keeping a busy schedule to cope with his grief, he urged adoption of the proposed constitution at a series of meetings around the state. His only concern with the document was its lack of an amendment process. The constitution was overwhelmingly ratified in May. Democrats wanted to nominate him for re-election, but he declined, citing problems "of a private and imperative character". Davis wrote "his problem – besides continuing sadness over his son's death – was money."

U.S. Representative

First term (1851–1853)

Breckinridge was a delegate to the January 8, 1851, state Democratic convention, which nominated Lazarus W. Powell for governor. A week later, he announced that he would seek election to Congress from Kentucky's Eighth District. Nicknamed the "Ashland district" because it contained Ashland, the estate of Whig Party founder Henry Clay, and much of the area Clay once represented, the district was a Whig stronghold. In the previous congressional election, Democrats had not even nominated a candidate. Breckinridge's opponent, Leslie Combs, was a former state legislator whose popularity was bolstered by his association with Clay and his participation in theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

; he was expected to win the election easily. In April, the candidates held a debate in Frankfort, and in May, they jointly canvassed the district, making daily speeches. Breckinridge reiterated his strict constructionist view of the U.S. Constitution and denounced the protective tariffs advocated by the Whigs, stating that "free thought needs free trade". His strong voice and charismatic personality contrasted with the campaign style of the much older Combs. On election day, he carried only three of the district's seven counties, but accumulated a two-to-one victory margin in Owen County, winning the county by 677 votes and the election by 537. Democrats carried five of Kentucky's 10 congressional districts, and Powell was elected as the first Democratic governor since 1834.

Supporters promoted Breckinridge for Speaker of the House, but he refused to allow his own nomination and voted with the majority to elect fellow Kentuckian Linn Boyd

Linn Boyd (November 22, 1800 – December 17, 1859) (also spelled "Lynn") was a prominent US politician of the 1840s and 1850s, and served as Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1851 to 1855. Boyd was elected to the Hou ...

. Despite this, the two were factional enemies, and Boyd assigned Breckinridge to the lightly regarded Committee on Foreign Affairs. Breckinridge's first speech, and several subsequent ones, were made to defend William Butler, again a presidential aspirant in 1852, from charges leveled by proponents of the Young America movement that he was too old and had not made his stance on slavery clear. The attacks came from the pages of George Nicholas Sanders's ''Democratic Review'', and on the House floor from several men, nearly all of whom supported Stephen Douglas for the nomination. These men included California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

's Edward C. Marshall, who was Breckinridge's cousin. Their attacks ultimately hurt Douglas's chances for the nomination, and Breckinridge's defense of Butler enhanced his own reputation. After this controversy, he was more active in the chamber's debates, but introduced few significant pieces of legislation. He defended the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 against attacks by Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

Representative Joshua Giddings, and opposed Andrew Johnson's proposed Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of Federal lands, government land or the American frontier, public domain, typically called a Homestead (buildings), homestead. In all, mo ...

out of concern that it would create more territories that excluded slavery. Despite his campaign rhetoric that federal funds should only be used for internal improvements "of a national character", he sought to increase Kentucky's federal allocation for construction and maintenance of rivers and harbors, and supported bills that benefited his district's hemp farmers.

Returning home from the legislative session, Breckinridge made daily visits with Henry Clay, who lay dying in Lexington, and was chosen to deliver Clay's eulogy in Congress when the next session commenced. The eulogy enhanced his popularity and solidified his position as Clay's political heir apparent. He also campaigned for the election of Democrat Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

as president. Although Pierce lost Kentucky by 3,200 votes, Breckinridge wielded more influence with him than he had with outgoing Whig President Millard Fillmore. A week after his inauguration, Pierce offered Breckinridge an appointment as governor of Washington Territory

The Washington Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

. He had initially sought the appointment, securing letters of recommendation from Powell and Butler, but by the time it was offered, he had decided to stay in Kentucky and seek re-election to the House.

Second term (1853–1855)

The Whigs, seeking to recapture Breckinridge's seat, nominated Attorney General of Kentucky James Harlan, but some Whig factions opposed him, and he withdrew in March. Robert P. Letcher, a former congressman and governor who had won 14 elections in Kentucky without a loss, was the party's second choice. Both candidates campaigned vigorously throughout the Eighth District, making multiple speeches a day between May and August. Letcher was an experienced campaigner, but his popular, anecdote-filled oratory was unpolished, and he was prone to outbursts of anger when frustrated. By contrast, Breckinridge delivered calm, well-reasoned speeches. Cassius Clay, a political enemy of Letcher's for years, endorsed Breckinridge, despite their differences on slavery. Citing this endorsement and the abolitionism of Breckinridge's uncles, Letcher tried to paint Breckinridge as an enemy of slavery. Breckinridge pointed to his consistent support for slavery and claimed Letcher was actually hostile to the interests of slaveholders. Although the district had gone for Whig candidate Winfield Scott by over 600 votes in the previous year's presidential election, Breckinridge defeated Letcher by 526 votes. Once again, he received a large margin in Owen County, which reported 123 more votes than eligible voters living in the county. Grateful for the support of the reliably Democratic county, he gave his son John Witherspoon Breckinridge the nickname "Owen".

Of the 234 members of the House, Breckinridge was among the 80 who were returned to their seats for the Thirty-third Congress. Due to his increased seniority, he was assigned to the more prestigious

The Whigs, seeking to recapture Breckinridge's seat, nominated Attorney General of Kentucky James Harlan, but some Whig factions opposed him, and he withdrew in March. Robert P. Letcher, a former congressman and governor who had won 14 elections in Kentucky without a loss, was the party's second choice. Both candidates campaigned vigorously throughout the Eighth District, making multiple speeches a day between May and August. Letcher was an experienced campaigner, but his popular, anecdote-filled oratory was unpolished, and he was prone to outbursts of anger when frustrated. By contrast, Breckinridge delivered calm, well-reasoned speeches. Cassius Clay, a political enemy of Letcher's for years, endorsed Breckinridge, despite their differences on slavery. Citing this endorsement and the abolitionism of Breckinridge's uncles, Letcher tried to paint Breckinridge as an enemy of slavery. Breckinridge pointed to his consistent support for slavery and claimed Letcher was actually hostile to the interests of slaveholders. Although the district had gone for Whig candidate Winfield Scott by over 600 votes in the previous year's presidential election, Breckinridge defeated Letcher by 526 votes. Once again, he received a large margin in Owen County, which reported 123 more votes than eligible voters living in the county. Grateful for the support of the reliably Democratic county, he gave his son John Witherspoon Breckinridge the nickname "Owen".

Of the 234 members of the House, Breckinridge was among the 80 who were returned to their seats for the Thirty-third Congress. Due to his increased seniority, he was assigned to the more prestigious Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

, but he was not given a committee chairmanship as many had expected. Although he supported Pierce's proslavery agenda on the principle of states' rights and believed that secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

was legal, he opposed secession as a remedy to the country's immediate problems. This, coupled with his earlier support of manumission and African colonization, balanced his support for slavery; most still considered him a moderate legislator.

An ally of Illinois' Stephen A. Douglas, Breckinridge supported the doctrine of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

as expressed in Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act. He believed passage of the act would remove the issue of slavery from national politics – although it ultimately had the opposite effect – and acted as a liaison between Douglas and Pierce to secure its passage. During the debate on the House floor, New York's Francis B. Cutting, incensed by a statement that Breckinridge had made, demanded that he explain or retract it. Breckinridge interpreted Cutting's demand as a challenge to duel. Under '' code duello'', the individual being challenged retained the right to name the weapons used and the distance between the combatants; Breckinridge chose rifles at 60 paces. He also specified that the duel should be held at Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially Unincorporated area, unincorporated, it is an edge city with a population of 81,015 at the 2020 ...

, the home of his friend Francis Preston Blair. Cutting, who had not intended his initial remark as a challenge, believed that Breckinridge's naming of terms constituted a challenge; he chose to use pistols at a distance of 10 paces. While the two men attempted to clarify who had issued the challenge and who reserved the right to choose the terms, mutual friends resolved the issue, preventing the duel. The recently adopted Kentucky Constitution prevented anyone who participated in a duel from holding elected office, and the peaceful resolution of the issue may have saved Breckinridge's political career.

Retirement from the House

In February 1854, the Whig majority in the Kentucky General Assembly passed – over Powell's veto – a reapportionment bill that redrew Breckinridge's district, removing Owen County and replacing it with Harrison and

In February 1854, the Whig majority in the Kentucky General Assembly passed – over Powell's veto – a reapportionment bill that redrew Breckinridge's district, removing Owen County and replacing it with Harrison and Nicholas

Nicholas is a male name, the Anglophone version of an ancient Greek name in use since antiquity, and cognate with the modern Greek , . It originally derived from a combination of two Ancient Greek, Greek words meaning 'victory' and 'people'. In ...

Counties. This, combined with the rise of the Know Nothing Party in Kentucky, left Breckinridge with little hope of re-election, and he decided to retire from the House at the expiration of his term. Following the December 1854 resignation of Pierre Soulé, the U.S. Minister to Spain, who failed to negotiate a U.S. annexation of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

following the controversial Ostend Manifesto, Pierce nominated Breckinridge to the position. Although the Senate confirmed the nomination, Breckinridge declined it on February 8, 1855, telling Pierce only that his decision was "of a private and domestic nature." His term in the house expired on March 4.

Desiring to care for his sick wife and rebuild his personal wealth, Breckinridge returned to his law practice in Lexington. In addition to his legal practice, he engaged in land speculation in Minnesota territory and Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

. When Governor Willis A. Gorman of the Minnesota Territory thwarted an attempt by Breckinridge's fellow investors (not including Breckinridge) to secure approval of a railroad connecting Dubuque, Iowa, with their investments near Superior, Wisconsin

Superior (; ) is a city in Douglas County, Wisconsin, United States, and its county seat. The population was 26,751 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located at the western end of Lake Superior in northwestern Wisconsin, the city l ...

, they petitioned Pierce to remove Gorman and appoint Breckinridge in his place. In 1855, Pierce authorized two successive investigations of Gorman, but failed to uncover any wrongdoing that would justify his removal. During his time away from politics, Breckinridge also promoted the advancement of horse racing in his native state and was chosen president of the Kentucky Association for the Improvement of the Breed of Horses.

Vice presidency (1857–1861)

As a delegate to the 1856 Democratic National Convention inCincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio, Breckinridge favored Pierce's renomination for president. When Pierce's hopes of securing the nomination faltered, Breckinridge joined other erstwhile Pierce backers by throwing his support behind his friend, Stephen Douglas. Even with this additional support, Douglas was still unable to garner two third's majority of the delegates' votes, and he withdrew, leaving James Buchanan as the Democratic presidential nominee. William Alexander Richardson, a Kentucky-born Representative from Illinois, then suggested that nominating Breckinridge for vice president would balance Buchanan's ticket and placate disgruntled supporters of Douglas or Pierce. A delegate from Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

placed his name before the convention, and although Breckinridge desired the vice presidential nomination, he declined, citing his deference to fellow Kentuckian and former House Speaker Linn Boyd, who was supported by the Kentucky delegation.

Ten men received votes on the first vice-presidential ballot. Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

's John A. Quitman had the most support with 59 votes. Eight state delegations – with a total of 55 votes – voted for Breckinridge in spite of his refusal of the nomination, making him the second-highest vote getter. Kentucky cast its 12 votes for Boyd, bringing his third-place total to 33 votes. Seeing Breckinridge's strength on the first ballot, large numbers of delegates voted for him on the second ballot, and those who did not soon saw that his nomination was inevitable and changed their votes to make it unanimous.

Unlike many political nominees of his time, Breckinridge actively campaigned for Buchanan and his election. During the first 10 days of September 1856, he spoke in Hamilton

Hamilton may refer to:

* Alexander Hamilton (1755/1757–1804), first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States

* ''Hamilton'' (musical), a 2015 Broadway musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda

** ''Hamilton'' (al ...

and Cincinnati, Ohio; Lafayette and Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

; Kalamazoo, Michigan

Kalamazoo ( ) is a city in Kalamazoo County, Michigan, United States, and its county seat. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Kalamazoo had a population of 73,598. It is the principal city of the Kalamazoo–Portage metropolitan are ...

; Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a list of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, United States. It is located at the confluence of the Ohio River, Ohio and Licking River (Kentucky), Licking rivers, across from Cincinnati to the north ...

; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

. His speeches stressed the idea that Republicans were fanatically devoted to emancipation, and their election would prompt the dissolution of the Union. Breckinridge's presence on the ticket helped the Democrats carry his home state of Kentucky, which the party had not won since 1828

Events

January–March

* January 4 – Jean Baptiste Gay, vicomte de Martignac succeeds the Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, Comte de Villèle, as Prime Minister of France.

* January 8 – The Democratic Party of the United States is organiz ...

, by 6,000 votes. Buchanan and Breckinridge received 174 electoral votes to 114 for Republicans John C. Frémont and William L. Dayton and eight for Know Nothing candidates Millard Fillmore and Andrew Jackson Donelson. Thirty-six years old at the time of his inauguration on March 4, 1857, Breckinridge was the youngest vice president in U.S. history, exceeding the minimum age required under the Constitution by only a year.

Buchanan resented that Breckinridge had supported both Pierce and Douglas before endorsing his nomination. Relations between the two were further strained, when upon asking for a private interview with Buchanan, Breckinridge was told to come to the White House and ask for Harriet Lane, who acted as the mansion's host for the unmarried president. Feeling slighted by the response, Breckinridge refused to carry out these instructions; later, three of Buchanan's intimates informed Breckinridge that requesting to speak to Miss Lane was actually a secret instruction to White House staff to usher the requestor into a private audience with the president. They also conveyed Buchanan's apologies for the misunderstanding.

Buchanan rarely consulted Breckinridge when making patronage appointments, and meetings between the two were infrequent. When Buchanan and Breckinridge endorsed the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state instead of allowing the people to vote, they managed to alienate most Northern Democrats, including Douglas. This disagreement ended plans for Breckinridge, Douglas, and Minnesota's Henry Mower Rice to build a series of three elaborate, conjoined

Buchanan rarely consulted Breckinridge when making patronage appointments, and meetings between the two were infrequent. When Buchanan and Breckinridge endorsed the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state instead of allowing the people to vote, they managed to alienate most Northern Democrats, including Douglas. This disagreement ended plans for Breckinridge, Douglas, and Minnesota's Henry Mower Rice to build a series of three elaborate, conjoined row house

A terrace, terraced house (British English, UK), or townhouse (American English, US) is a type of medium-density housing which first started in 16th century Europe with a row of joined houses party wall, sharing side walls. In the United States ...

s in which to live during their time in Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

. In November 1857, after Breckinridge found alternative lodging in Washington, he sold a slave woman and her young infant, which according to historian James C. Klotter, probably ended his days as a slaveholder. When Breckinridge did not travel to Illinois to campaign for Douglas's re-election to the Senate and gave him only a lukewarm endorsement, relations between them worsened.

Functioning as the Senate's presiding officer, Breckinridge's participation in the chamber's debates was also restricted, but he won respect for presiding "gracefully and impartially." On January 4, 1859, he was asked to deliver the final address in the Old Senate Chamber; in the speech, he expressed his desire that the Congress find a solution that would preserve the Union. During its half century in the chamber, the Senate had grown from 32 to 64 members. During those years, he observed, the Constitution had "survived peace and war, prosperity and adversity" to protect "the larger personal freedom compatible with public order." Breckinridge expressed hope that eventually "another Senate, in another age, shall bear to a new and larger Chamber, this Constitution vigorous and inviolate, and that the last generation of posterity shall witness the deliberations of the Representatives of American States, still united, prosperous, and free." Breckinridge then led a procession to the new chamber. Breckinridge opposed the idea that the federal government could coerce action by a state, but maintained that secession, while legal, was not the solution to the country's problems.

Although John Crittenden's Senate term did not expire until 1861, the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in th ...

met to choose his successor in 1859. Until just days before the election, the contest was expected to be between Breckinridge and Boyd, who had been elected lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

in August; Boyd's worsening health prompted his withdrawal on November 28, 1859. On December 12, the Assembly chose Breckinridge over Joshua Fry Bell, the defeated candidate in the August gubernatorial election, by a vote of 81–53. In his acceptance speech, delivered to the Kentucky House of Representatives on December 21, Breckinridge endorsed the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

's decision in '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'', which ruled that Congress could not restrict slavery in the territories, and insisted that John Brown's recent raid on Harpers Ferry was evidence of Republicans' insistence on either "negro equality" or violence. Resistance in some form, he predicted, would eventually be necessary. He still urged the assembly against secession – "God forbid that the step shall ever be taken!" – but his discussion of growing sectional conflict bothered some, including his uncle Robert.

Presidential campaign of 1860

Early in 1859, SenatorJames Henry Hammond

James Henry Hammond (November 15, 1807 – November 13, 1864) was an American attorney, politician, and Planter (American South), planter. He served as a United States representative from 1835 to 1836, the 60th Governor of South Carolina from 1842 ...

of South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

reported to a friend that Breckinridge was seeking the Democratic presidential nomination, but as late as January 1860, Breckinridge told family members that he had no desire for the nomination. A ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' editorial noted that while Buchanan was falling "in prestige and political consequence, the star of the Vice President rises higher above the clouds." Douglas, considered the frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination, was convinced that Breckinridge would be a candidate; this, combined with Buchanan's reluctant support of Breckinridge and Breckinridge's public support for a federal slave code, deepened the rift between the two.

Among Breckinridge's supporters at the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, were several prominent Kentuckians. They were former Kentucky Governor and current Senator Lazarus W. Powell, former Kentucky Representative William Preston (a distant relative), law partner James Brown Clay, and James B. Beck. Breckinridge did not attend the convention, but instructed his supporters not to nominate him as long as James Guthrie remained a candidate. Accordingly, when a delegate from Arkansas nominated Breckinridge for president on the 36th ballot, Beck asked that it be withdrawn, and the request was honored. Over the course of 57 ballots, Douglas maintained a wide plurality, but failed to gain the necessary two-thirds majority; Guthrie consistently ran second. Unable to nominate a candidate, delegates voted to reconvene in Baltimore, Maryland, on June 18.

Pro-Southern delegates, who had walked out of the Charleston convention in protest of its failure to adopt a federal slave code plank in its platform, did not participate in the Baltimore convention. The delegates from Alabama and Louisiana – all of whom had walked out at Charleston – had been replaced, after five days of debate and holding votes on the issue, with Douglas supporters from those states, leading to the nomination of Douglas and Herschel Vespasian Johnson for president and vice president, respectively, on the sixth day. The protesting delegates convened on the same day in Baltimore. On the first ballot, Breckinridge received 81 votes, with 24 going to former senator Daniel S. Dickinson of New York. Dickinson supporters gradually changed their support to Breckinridge to make his nomination unanimous, and Joseph Lane of Oregon was chosen by acclamation as his vice presidential running mate. Despite concerns about the breakup of the party, Breckinridge accepted the presidential nomination. In August, Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis attempted to broker a compromise under which Douglas, Breckinridge, and Tennessee's John Bell, the nominee of the Constitutional Union Party, would all withdraw in favor of a compromise candidate. Both Breckinridge and Bell readily agreed to the plan, but Douglas was opposed to compromising with the "Bolters", and his supporters retained an intense dislike for Breckinridge that made them averse to Davis's proposal.

Opponents knew Breckinridge believed in the right of secession and accused him of favoring the breakup of the Union; he denied the latter during a speech in Frankfort: "I am an American citizen, a Kentuckian who never did an act nor cherished a thought that was not full of devotion to the Constitution and the Union." While he had very little support in the northern states, most, if not all, of the southern states were expected to go for Breckinridge. This would give him only 120 of 303 electoral votes, but to gain support from any northern states, he had to minimize his connections with the southern states and risked losing their support to Bell. Some Breckinridge supporters believed his best hope was for the election to be thrown to the House of Representatives; if he could add the support of some Douglas or Bell states to the 13 believed to support him, he could beat Lincoln, who was believed to carry the support of 15 states. To Davis's wife, Varina, Breckinridge wrote, "I trust I have the courage to lead a forlorn hope."

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, his support in those states came mostly from rural areas with low slave populations; the urban areas with higher slave populations generally went for Bell or Douglas. Breckinridge also carried the border states of Maryland and Delaware. Historian James C. Klotter points out in light of these results that, while Douglas maintained that there was "not a disunionist in America who is not a Breckinridge man", it is more likely that party loyalty and economic status played a more prominent role in Breckinridge's support than did issues of slavery and secession. He lost to Douglas in Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

and Bell in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and Tennessee. Bell also captured Breckinridge's home state, Kentucky. Lincoln swept most of the northern states, although New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

split its electoral votes, giving four to Lincoln and three to Douglas. As the candidate of the Buchanan faction, Breckinridge outpolled Douglas in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

and received support comparable to Douglas in Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

, although he received very little support elsewhere in the North. It was Breckinridge's duty as vice president to announce Lincoln as the winner of the electoral college vote on February 13, 1861.

On February 24, Breckinridge visited Lincoln at Willard's Hotel in Washington, DC, and frequently thereafter he visited his step-cousin, now the First Lady, at the White House. In the lame duck session following the election, Congress adopted a resolution authored by Lazarus Powell, now in the Senate, calling for a committee of thirteen (Committee of Thirteen on the Disturbed Condition of the Country) "to consider that portion of the President's message relating to the disturbances of the country." Frank Heck wrote that Breckinridge appointed "an able committee, representing every major faction." He endorsed Crittenden's proposed compromise, a collection of constitutional amendments designed to avert secession and appease the South. Breckinridge used his influence as the Senate's presiding officer in an unsuccessful attempt to get it approved by either the committee or the Senate. Ultimately, the committee reported that they were unable to agree on a recommendation. On March 4, 1861, the last day of the session, Breckinridge swore in Hannibal Hamlin as his successor as vice president. Hamlin, in turn, swore in the newly elected senators, including Breckinridge.

U.S. Senator

Seven states had already seceded when Breckinridge took his seat as a senator, leaving the remaining Southern senators more outnumbered in their defense of slavery. Seeking to find a compromise that would reunite the states under constitutional principles, he urged Lincoln to withdraw federal forces from the Confederate states to avert war. The congressional session ended on March 28, and in an April 2 address to the Kentucky General Assembly, he continued to advocate peaceful reconciliation of the states and proposed a conference of border states to seek a solution. On April 12, Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter, ending plans for the conference. Breckinridge recommended that Governor Beriah Magoffin call a sovereignty convention to determine whether Kentucky would side with the Union or the Confederacy. On May 10, he was chosen by the legislature as one of six delegates to a conference to decide the state's next action. The states' rights delegates were Breckinridge, Magoffin, and Richard Hawes; the Unionist delegates were Crittenden, Archibald Dixon, and S.S. Nicholas. Unable to agree on substantial issues, the delegates recommended that Kentucky adopt a neutral stance in the Civil War and arm itself to prevent invasion by either federal or Confederate forces. Breckinridge did not support this recommendation, but he agreed to abide by it once it was approved by the legislature. In special elections in June, pro-Union candidates captured 9 of 10 seats in Kentucky's House delegation. Returning to the Senate for a special session in July, Breckinridge was regarded as a traitor by most of his fellow legislators because of his Confederate sympathies. He condemned as unconstitutional Lincoln's enlistment and arming of men for a war Congress had not officially declared, his expending funds for the war that had not been allocated by Congress, and his suspension of the writ ofhabeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

. He was the only senator to vote against a resolution authorizing Lincoln to use "the entire resources of the government" for the war. Asked what he would do if he were president, he replied, "I would prefer to see these States all reunited upon true constitutional principles to any other object that could be offered me in life. But I infinitely prefer to see a peaceful separation of these States than to see endless, aimless, devastating war, at the end of which I see the grave of public liberty and of personal freedom." On August 1, he declared that, if Kentucky sided with the federal government against the Confederacy, "she will be represented by some other man on the floor of this Senate."

Kentucky's neutrality was breached by both federal and Confederate forces in early September 1861 (the Federal forces maintained that there had been no breach, as Kentucky was an integral part of the Union). Confederate forces invaded Kentucky on September 3; they were followed by a Union force commanded by Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, which on the morning of September 6 occupied the town of Paducah on the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

. Soon after, Unionists in the state arrested former governor Charles S. Morehead for his suspected Confederate sympathies and shut down the '' Louisville Courier'' because of its pro-Confederate editorials. Word reached Breckinridge that Union General Thomas E. Bramlette intended to arrest him next. To avoid detainment, on September 19, 1861, he left Lexington. Joined in Prestonsburg by Confederate sympathizers George W. Johnson, George Baird Hodge, William Preston, and William E. Simms, he continued to Abingdon, Virginia, and from there by rail to Confederate-held Bowling Green, Kentucky. The state legislature immediately requested his resignation.

In an open letter to his constituents dated October 8, 1861, Breckinridge maintained that the Union no longer existed and that Kentucky should be free to choose her own course; he defended his sympathy to the Southern cause and denounced the Unionist state legislature, declaring, "I exchange with proud satisfaction a term of six years in the Senate of the United States for the musket of a soldier." He was indicted for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

in U.S. federal district court in Frankfort on November 6, 1861, having officially enlisted in the Confederate army days earlier. On December 2, 1861, he was declared a traitor by the U.S. Senate. A resolution stating "Whereas John C. Breckinridge, a member of this body from the State of Kentucky, has joined the enemies of his country, and is now in arms against the government he had sworn to support: Therefore—Resolved, That said John C. Breckinridge, the traitor, be, and he hereby is, expelled from the Senate," was adopted by a vote of 36–0 on December 4. Ten Southern Senators had been expelled earlier that year in July.

American Civil War

Service in the Western Theater

On the recommendation ofSimon Bolivar Buckner

Simon Bolivar Buckner ( ; April 1, 1823 – January 8, 1914) was an American soldier, Confederate military officer, and politician. He fought in the United States Army in the Mexican–American War. He later fought in the Confederate State ...

, the former commander of the Kentucky State Militia who had also joined the Confederate Army, Breckinridge was commissioned as a brigadier general on November 2, 1861. On November 16, he was given command of the 1st Kentucky Brigade. Nicknamed the Orphan Brigade because its men felt orphaned by Kentucky's Unionist state government, the brigade was in Buckner's 2nd Division of the Army of Mississippi, commanded by General Albert Sidney Johnston

General officer, General Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) was an American military officer who served as a general officer in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States ...

. For several weeks, he trained his troops in the city, and he also participated in the organization of a provisional Confederate government for the state. Although not sanctioned by the legislature in Frankfort, its existence prompted the Confederacy to admit Kentucky on December 10, 1861.

Johnston's forces were forced to withdraw from Bowling Green in February 1862. During the retreat, Breckinridge was put in charge of Johnston's Reserve Corps. Johnston decided to attack Ulysses S. Grant's forces at Shiloh, Tennessee on April 6, 1862, by advancing North from his base in Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in and the county seat of Alcorn County, Mississippi, Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,622 at the 2020 census. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835. It lies on the state line with Tennessee.

His ...