J.G. Frazer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish

The

The

Animals which shed their skin, such as

Animals which shed their skin, such as

The

The

''Taboo and the Perils of the Soul''

(1911) * ''The Gorgon's Head and other Literary Pieces'' (1927) * ''The Worship of Nature'' (1926) (from 1923–25 Gifford Lectures,Gifford Lecture Series – Books

at www.giffordlectures.org )

* '' The Library'', by Apollodorus (text, translation and notes), 2 volumes (1921): (vol. 1); (vol. 2)

* '' Folk-lore in the Old Testament'' (1918)

* ''The Belief in Immortality and the Worship of the Dead'', 3 volumes (1913–24)

* ''

''Pausanias, and other Greek sketches''

(1900)

''Description of Greece''

by Pausanias (translation and commentary) (1897–) 6 volumes. * ''The Golden Bough: a Study in Magic and Religion'', 1st edition (1890) * '' Totemism'' (1887) * Jan Harold Brunvard, ''American Folklore; An Encyclopedia'', ''s.v.'' "Superstition" (p 692-697)

“J. G. Frazer and Religion”

in ''BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology'', Paris. *Ackerman, Robert, 2018

« L’anthropologue qui meurt et ressuscite : vie et œuvre de James George Frazer »

in Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie * * * * * *

BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology

"Frazer, James George (1854-1941)", Paris, 2015. (ISSN 2648-2770) *

at Bartleby.com * * *

Trinity College Chapel: Sir James George Frazer

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Frazer, James 1854 births 1941 deaths Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Social anthropologists Anthropologists of religion Lawyers from Glasgow Mythographers Comparative mythology Scottish anthropologists Scottish classical scholars Scottish scholars and academics Scottish lawyers Alumni of the University of Glasgow Academics of the University of Liverpool Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Members of the Middle Temple Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People from Helensburgh Fellows of the British Academy People educated at Larchfield Academy Researchers of Slavic religion Scottish folklorists Scholars of comparative religion Writers about religion and science Comparative mythologists

social anthropologist

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In t ...

and folklorist

Folklore studies, less often known as folkloristics, and occasionally tradition studies or folk life studies in the United Kingdom, is the branch of anthropology devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currenc ...

influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narra ...

and comparative religion

Comparative religion is the branch of the study of religions with the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices, themes and impacts (including migration) of the world's religions. In general the comparative study of religion yie ...

.

Personal life

He was born on 1 January 1854 inGlasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, Scotland, the son of Katherine Brown and Daniel F. Frazer, a chemist.

Frazer attended school at Springfield Academy and Larchfield Academy in Helensburgh

Helensburgh (; gd, Baile Eilidh) is an affluent coastal town on the north side of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland, situated at the mouth of the Gareloch. Historically in Dunbartonshire, it became part of Argyll and Bute following local gove ...

. He studied at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, where he graduated with honours in classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

(his dissertation was published years later as ''The Growth of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's Ideal Theory'') and remained a Classics Fellow all his life. From Trinity, he went on to study law at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's I ...

, but never practised.

Four times elected to Trinity's Title Alpha Fellowship, he was associated with the college for most of his life, except for the year 1907–1908, spent at the University of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

. He was knighted in 1914, and a public lectureship in social anthropology at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford, Glasgow and Liverpool was established in his honour in 1921. He was, if not blind, then severely visually impaired from 1930 on. He and his wife, Lilly, died in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, England, within a few hours of each other. He died on 7 May 1941. They are buried at the Ascension Parish Burial Ground

The Ascension Parish Burial Ground, formerly known as the burial ground for the parish of St Giles and St Peter's, is a cemetery off Huntingdon Road in Cambridge, England. Many notable University of Cambridge academics are buried there, includ ...

in Cambridge.

His sister Isabella Katherine Frazer married the mathematician John Steggall.

Frazer is commonly interpreted as an atheist in light of his criticism of Christianity and especially Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in ''The Golden Bough

''The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion'' (retitled ''The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion'' in its second edition) is a wide-ranging, comparative study of mythology and religion, written by the Scottish anthropologist Sir ...

''. However, his later writings and unpublished materials suggest an ambivalent relationship with Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ...

and Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

.

In 1896 Frazer married Elizabeth "Lilly" Grove, a writer whose family was from Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

. She would later adapt Frazer's ''Golden Bough'' as a book of children's stories, ''The Leaves from the Golden Bough''.

His work

The study of myth and religion became his areas of expertise. Except for visits toItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, Frazer was not widely travelled. His prime sources of data were ancient histories and questionnaires mailed to missionaries and imperial officials all over the globe. Frazer's interest in social anthropology was aroused by reading E. B. Tylor's ''Primitive Culture'' (1871) and was also encouraged by his friend, the biblical scholar William Robertson Smith

William Robertson Smith (8 November 184631 March 1894) was a Scottish orientalist, Old Testament scholar, professor of divinity, and minister of the Free Church of Scotland. He was an editor of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' and contributo ...

, who was comparing elements of the Old Testament with early Hebrew folklore.

Frazer was the first scholar to describe in detail the relations between myths and rituals. His vision of the annual sacrifice of the Year-King has not been borne out by field studies. Yet ''The Golden Bough

''The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion'' (retitled ''The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion'' in its second edition) is a wide-ranging, comparative study of mythology and religion, written by the Scottish anthropologist Sir ...

'', his study of ancient cults, rites, and myths, including their parallels in early Christianity, continued for many decades to be studied by modern mythographers for its detailed information.

The first edition, in two volumes, was published in 1890; and a second, in three volumes, in 1900. The third edition was finished in 1915 and ran to twelve volumes, with a supplemental thirteenth volume added in 1936. He published a single-volume abridged version, largely compiled by his wife Lady Frazer, in 1922, with some controversial material on Christianity excluded from the text. The work's influence extended well beyond the conventional bounds of academia, inspiring the new work of psychologists and psychiatrists. Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

, the founder of psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might ...

, cited ''Totemism and Exogamy'' frequently in his own ''Totem and Taboo

''Totem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics'', or ''Totem and Taboo: Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics'', (german: Totem und Tabu: Einige Übereinstimmungen im Seelenl ...

: Resemblances Between the Psychic Lives of Savages and Neurotics''.

The symbolic cycle of life, death and rebirth which Frazer divined behind myths of many peoples captivated a generation of artists and poets. Perhaps the most notable product of this fascination is T. S. Eliot's poem ''The Waste Land

''The Waste Land'' is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important poems of the 20th century and a central work of Modernist poetry in English, modernist poetry. Published in 1922, the 434-line poem first appeared in the ...

'' (1922).

Frazer's pioneering work has been criticised by late-20th-century scholars. For instance, in the 1980s the social anthropologist Edmund Leach wrote a series of critical articles, one of which was featured as the lead in '' Anthropology Today'', vol. 1 (1985). Leach criticised ''The Golden Bough'' for the breadth of comparisons drawn from widely separated cultures, but often based his comments on the abridged edition, which omits the supportive archaeological details. In a positive review of a book narrowly focused on the '' cultus'' in the Hittite city of Nerik, J. D. Hawkins remarked approvingly in 1973, "The whole work is very methodical and sticks closely to the fully quoted documentary evidence in a way that would have been unfamiliar to the late Sir James Frazer." More recently, ''The Golden Bough'' has been criticized for what are widely perceived as imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

, anti-Catholic, classist and racist elements, including Frazer's assumptions that European peasants, Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait ...

and Africans

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

represented fossilized, earlier stages of cultural evolution.

Another important work by Frazer is his six-volume commentary on the Greek traveller Pausanias' description of Greece in the mid-2nd century AD. Since his time, archaeological excavations have added enormously to the knowledge of ancient Greece, but scholars still find much of value in his detailed historical and topographical discussions of different sites, and his eyewitness accounts of Greece at the end of the 19th century.

Theories of Religion and Cultural Evolution

Among the most influential elements of the third edition of ''The Golden Bough'' is Frazer's theory ofcultural evolution

Cultural evolution is an evolutionary theory of social change. It follows from the definition of culture as "information capable of affecting individuals' behavior that they acquire from other members of their species through teaching, imitation ...

and the place Frazer assigns religion and magic in that theory. Frazer's theory of cultural evolution was not absolute and could reverse, but sought to broadly describe three (or possibly, four) spheres through which cultures were thought to pass over time. Frazer believed that, over time, culture passed through three stages, moving from magic, to religion, to science. Frazer's classification notably diverged from earlier anthropological descriptions of cultural evolution, including that of Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...

, because he claimed magic was both initially separate from religion and invariably preceded religion. He also defined magic separately from belief in the supernatural and superstition, presenting an ultimately ambivalent view of its place in culture.

Frazer believed that magic and science were similar because both shared an emphasis on experimentation and practicality; his emphasis on this relationship is so broad that almost any disproven scientific hypothesis technically constitutes magic under his system. In contrast to both magic and science, Frazer defined religion in terms of belief in personal, supernatural forces and attempts to appease them. As historian of religion Jason Josephson-Storm describes Frazer's views, Frazer saw religion as "a momentary aberration in the grand trajectory of human thought." He thus ultimately proposed – and attempted to further – a narrative of secularization

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses ...

and one of the first social-scientific expressions of a disenchantment

In social science, disenchantment (german: Entzauberung) is the cultural rationalization and devaluation of religion apparent in modern society. The term was borrowed from Friedrich Schiller by Max Weber to describe the character of a modern ...

narrative.

At the same time, Frazer was aware that both magic and religion could persist or return. He noted that magic sometimes returned so as to become science, such as when alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wo ...

underwent a revival in Early Modern Europe and became chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

. On the other hand, Frazer displayed a deep anxiety about the potential of widespread belief in magic to empower the masses, indicating fears of and biases against lower-class people in his thought.

Origin-of-death stories

Frazer collected stories from throughout the British Empire and devised four general classifications into which many of them could be grouped:The Story of the Two Messengers

This type of story is common in Africa. Two messages are carried from the supreme being to mankind: one of eternal life and one of death. The messenger carrying the tidings of eternal life is delayed, and so the message of death is received first by mankind. TheBantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

people of Southern Africa, such as the Zulu, tell that Unkulunkulu Unkulunkulu (/uɲɠulun'ɠulu/), often formatted as uNkulunkulu,Weir, Jennifer. "Whose Unkulunkulu?" ''Africa (pre-2011)'', vol. 75, no. 2, 2005, pp. 203-219''.'' is the Supreme Creator in the language of the Zulu people. Originally a "first ancest ...

, the Old Old One, sent a message that men should not die, giving it to the chameleon

Chameleons or chamaeleons (family Chamaeleonidae) are a distinctive and highly specialized clade of Old World lizards with 202 species described as of June 2015. The members of this family are best known for their distinct range of colors, bein ...

. The chameleon was slow and dawdled, taking time to eat and sleep. Unkulunkulu meanwhile had changed his mind and gave a message of death to the lizard who travelled quickly and so overtook the chameleon. The message of death was delivered first and so, when the chameleon arrived with its message of life, mankind would not hear it and so is fated to die.

Because of this, Bantu people, such as the Ngoni, punish lizards and chameleons. For example, children may be allowed to put tobacco into a chameleon's mouth so that the nicotine

Nicotine is a naturally produced alkaloid in the nightshade family of plants (most predominantly in tobacco and '' Duboisia hopwoodii'') and is widely used recreationally as a stimulant and anxiolytic. As a pharmaceutical drug, it is use ...

poisons it and the creature dies, writhing while turning colours.

Variations of the tale are found in other parts of Africa. The Akamba

The Kamba or Akamba (sometimes called Wakamba) people are a Bantu ethnic group who predominantly live in the area of Kenya stretching from Nairobi to Tsavo and north to Embu, in the southern part of the former Eastern Province. This land is ...

say the messengers are the chameleon and the thrush

''The Man from U.N.C.L.E.'' is an American spy fiction television series produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Television and first broadcast on NBC. The series follows secret agents, played by Robert Vaughn and David McCallum, who work for a secret ...

while the Ashanti say they are the goat and the sheep.

The Bura people of northern Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

say that, at first, neither death nor disease existed but, one day, a man became ill and died. The people sent a worm to ask the sky deity, Hyel, what they should do with him. The worm was told that the people should hang the corpse in the fork of a tree and throw mush at it until it came back to life. But a malicious lizard, Agadzagadza, hurried ahead of the worm and told the people to dig a grave, wrap the corpse in cloth, and bury it. The people did this. When the worm arrived and said that they should dig up the corpse, place it in a tree, and throw mush at it, they were too lazy to do this, and so death remained on Earth. This Bura story has the common mythic motif of a vital message which is diverted by a trickster

In mythology and the study of folklore and religion, a trickster is a character in a story ( god, goddess, spirit, human or anthropomorphisation) who exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge and uses it to play tricks or otherwi ...

.

In Togoland

Togoland was a German Empire protectorate in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400 km2 (29,867 sq mi) in size. During the period ...

, the messengers were the dog and the frog, and, as in the Bura version, the messengers go first from mankind to God to get answers to their questions.

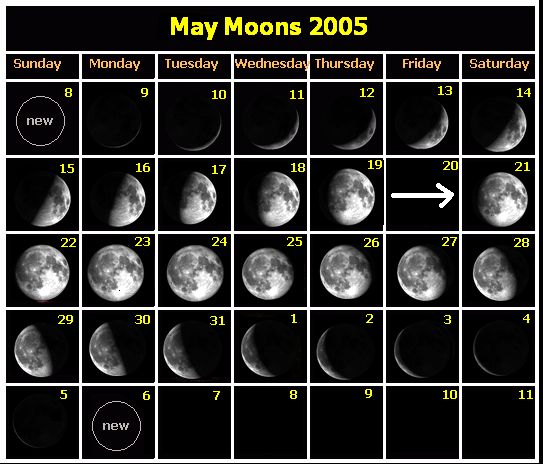

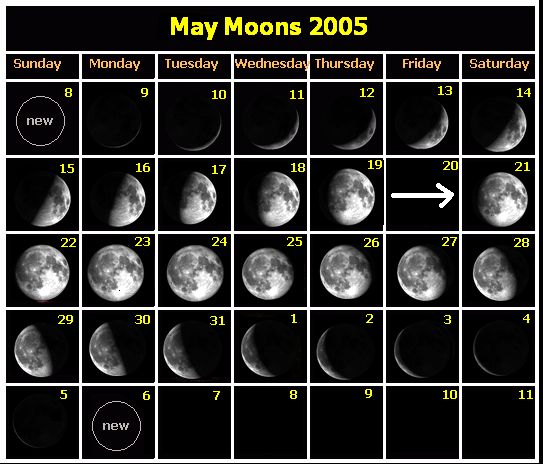

The Story of the Waxing and Waning Moon

The

The moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

regularly seems to disappear and then return. This gave primitive peoples the idea that man should or might return from death in a similar way. Stories that associate the moon with the origin of death are found especially around the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

region. In Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

, it is said that the moon suggested that mankind should return as he did. But the rat god, ''Ra Kalavo'', would not permit this, insisting that men should die like rats. In Australia, the Wotjobaluk aborigines say that the moon used to revive the dead until an old man said that this should stop. The Cham have it that the goddess of good luck used to revive the dead, but the sky-god sent her to the moon so she could not do this any more.

The Story of the Serpent and His Cast Skin

snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more ...

s and lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia altho ...

s, appeared to be immortal to primitive people. This led to stories in which mankind lost the ability to do this. For example, in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

, it was said that the Jade Emperor

The Jade Emperor or Yudi ( or , ') in Chinese culture, traditional religions and myth is one of the representations of the first god ( '). In Daoist theology he is the assistant of Yuanshi Tianzun, who is one of the Three Pure Ones, the th ...

sent word from heaven to mankind that, when they became old, they should shed their skins while the serpents would die and be buried. But some snakes overheard the command and threatened to bite the messenger unless he switched the message, so that man would die while snakes would be eternally renewed. For the natives of the island of Nias

Nias ( id, Pulau Nias, Nias language: ''Tanö Niha'') (sometimes called Little Sumatra in English) is an island located off the western coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. Nias is also the name of the archipelago () of which the island is the centre ...

, the story was that the messenger who completed their creation failed to fast

Fast or FAST may refer to:

* Fast (noun), high speed or velocity

* Fast (noun, verb), to practice fasting, abstaining from food and/or water for a certain period of time

Acronyms and coded Computing and software

* ''Faceted Application of Subje ...

and ate banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", disting ...

s rather than crabs. If he had eaten the latter, then mankind would have shed their skins like crabs and so lived eternally.

The Story of the Banana

The

The banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", disting ...

plant bears its fruit on a stalk which dies after bearing. This gave people such as the Nias islanders the idea that they had inherited this short-lived property of the banana rather than the immortality of the crab. The natives of Poso also based their myth on this property of the banana. Their story is that the creator in the sky would lower gifts to mankind on a rope and, one day, a stone was offered to the first couple. They refused the gift as they did not know what to do with it, so the creator took it back and lowered a banana. The couple ate this with relish, but the creator told them that they would live as the banana, perishing after having children rather than remaining everlasting like the stone.

Reputation and criticism

According to historian Timothy Larsen, Frazer used scientific terminology and analogies to describe ritual practices, and conflated magic and science together, such as describing the "magic wand of science". Larsen criticizes Frazer for baldly characterized magical rituals as "infallible" without clarifying that this is merely what believers in the rituals thought. Larsen has said that Frazer's vivid descriptions of magical practices were written with the intention to repel readers, but, instead, these descriptions more often allured them. Larsen also criticizes Frazer for applying western European Christian ideas, theology, and terminology to non-Christian cultures. This distorts those cultures to make them appear more Christian. Frazer routinely described non-Christian religious figures by equating them with Christian ones. Frazer applied Christian terms to functionaries, for instance calling the elders of the Njamus ofEast Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

"equivalent to the Levites

Levites (or Levi) (, he, ''Lǝvīyyīm'') are Jewish males who claim patrilineal descent from the Tribe of Levi. The Tribe of Levi descended from Levi, the third son of Jacob and Leah. The surname ''Halevi'', which consists of the Hebrew de ...

of Israel" and the Grand Lama of Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhasa ...

"the Buddhist Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

... the man-god who bore his people's sorrows, the Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd ( el, ποιμὴν ὁ καλός, ''poimḗn ho kalós'') is an image used in the pericope of , in which Jesus Christ is depicted as the Good Shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep. Similar imagery is used in Psalm 23 ...

who laid down his life for the sheep". He routinely uses the specifically Christian theological terms "born again

Born again, or to experience the new birth, is a phrase, particularly in evangelicalism, that refers to a "spiritual rebirth", or a regeneration of the human spirit. In contrast to one's physical birth, being "born again" is distinctly and se ...

", "new birth", "baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

", " christening", "sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the rea ...

", and "unclean" in reference to non-Christian cultures.

When Frazer's Australian colleague Walter Baldwin Spencer

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (23 June 1860 – 14 July 1929), commonly referred to as Baldwin Spencer, was a British-Australian evolutionary biologist, anthropologist and ethnologist.

He is known for his fieldwork with Aboriginal peoples in ...

requested to use native terminology to describe Aboriginal Australian

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait I ...

cultures, arguing that doing so would be more accurate, since the Christian terms were loaded with Christian connotations that would be completely foreign to members of the cultures he was describing, Frazer insisted that he should use Judeo-Christian terms instead, telling him that using native terms would be off-putting and would seem pedantic. A year later, Frazer excoriated Spencer for refusing to equate the non-estrangement of Aboriginal Australian totem

A totem (from oj, ᑑᑌᒼ, italics=no or '' doodem'') is a spirit being, sacred object, or symbol that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, lineage, or tribe, such as in the Anishinaabe clan system.

While ''the ...

s with the Christian doctrine of reconciliation. When Spencer, who had studied the aboriginals firsthand, objected that the ideas were not remotely similar, Frazer insisted that they were exactly equivalent. Based on these exchanges, Larsen concludes that Frazer's deliberate use of Judeo-Christian terminology in the place of native terminology was not to make native cultures seem less strange, but rather to make Christianity seem more strange and barbaric.

Selected works

* ''Creation and Evolution in Primitive Cosmogenies, and Other Pieces'' (1935) * ''The Fear of the Dead in Primitive Religion'' (1933–36) * ''Condorcet on the Progress of the Human Mind'' (1933) * ''Garnered Sheaves'' (1931) * ''The Growth of Plato's Ideal Theory'' (1930) * ''Myths of the Origin of Fire'' (1930) * '' Fasti'', byOvid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom ...

(text, translation and commentary), 5 volumes (1929)

** one-volume abridgement (1931)

*** revised by G. P. Goold (1989, corr. 1996):

* ''Devil's Advocate'' (1928)

* ''Man, God, and Immortality'' (1927)

''Taboo and the Perils of the Soul''

(1911) * ''The Gorgon's Head and other Literary Pieces'' (1927) * ''The Worship of Nature'' (1926) (from 1923–25 Gifford Lectures,

at www.giffordlectures.org

The Golden Bough

''The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion'' (retitled ''The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion'' in its second edition) is a wide-ranging, comparative study of mythology and religion, written by the Scottish anthropologist Sir ...

'', 3rd edition: 12 volumes (1906–15; 1936)

** 1922 one-volume abridgement:

* ''Totemism and Exogamy'' (1910)

* ''Psyche's Task'' (1909)

* ''The Golden Bough'', 2nd edition: expanded to 3 volumes (1900)

''Pausanias, and other Greek sketches''

(1900)

''Description of Greece''

by Pausanias (translation and commentary) (1897–) 6 volumes. * ''The Golden Bough: a Study in Magic and Religion'', 1st edition (1890) * '' Totemism'' (1887) * Jan Harold Brunvard, ''American Folklore; An Encyclopedia'', ''s.v.'' "Superstition" (p 692-697)

See also

References

Further reading

* * * Ackerman, Robert, (2015)“J. G. Frazer and Religion”

in ''BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology'', Paris. *Ackerman, Robert, 2018

« L’anthropologue qui meurt et ressuscite : vie et œuvre de James George Frazer »

in Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie * * * * * *

Giacomo Scarpelli

Giacomo Scarpelli (born 23 May 1956), son of Furio Scarpelli, is an Italian scholar in History of Philosophy and screenwriter.

Early life

Scarpelli was born in Rome, Italy. He obtained a Ph.D. in Philosophy at the University of Florence, and car ...

, ''Il razionalista pagano. Frazer e la filosofia del mito'', Milano, Meltemi 2018

External links

* Resources related to researchBEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology

"Frazer, James George (1854-1941)", Paris, 2015. (ISSN 2648-2770) *

at Bartleby.com * * *

Trinity College Chapel: Sir James George Frazer

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Frazer, James 1854 births 1941 deaths Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Social anthropologists Anthropologists of religion Lawyers from Glasgow Mythographers Comparative mythology Scottish anthropologists Scottish classical scholars Scottish scholars and academics Scottish lawyers Alumni of the University of Glasgow Academics of the University of Liverpool Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Members of the Middle Temple Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People from Helensburgh Fellows of the British Academy People educated at Larchfield Academy Researchers of Slavic religion Scottish folklorists Scholars of comparative religion Writers about religion and science Comparative mythologists