Italian Tripolitania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Italian Tripolitania was an Italian colony, located in present-day western

At the end of

At the end of

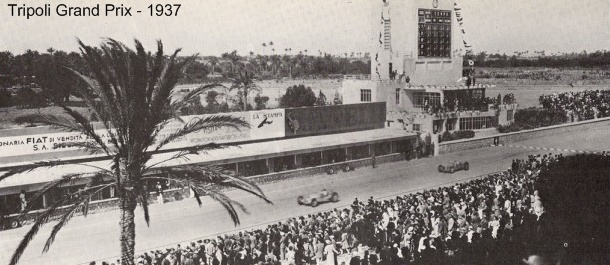

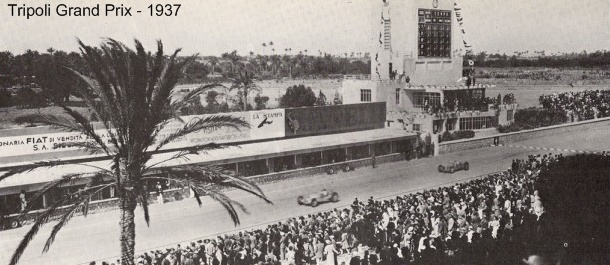

A large number of Italian colonists moved to Tripolitania in the late 1930s. These settlers went primarily to the area of Sahel al-Jefara, in Tripolitania, and to the capital Tripoli. In 1939 there were in all Tripolitania nearly 60,000 Italians, most living in Tripoli (whose population was nearly 45% Italian). As a consequence, huge economic improvements arose in all coastal Tripolitania. For example, Italians created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an internationally renowned automobile race. Certain rights were guaranteed to autochthonous Libyans (later called by

A large number of Italian colonists moved to Tripolitania in the late 1930s. These settlers went primarily to the area of Sahel al-Jefara, in Tripolitania, and to the capital Tripoli. In 1939 there were in all Tripolitania nearly 60,000 Italians, most living in Tripoli (whose population was nearly 45% Italian). As a consequence, huge economic improvements arose in all coastal Tripolitania. For example, Italians created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an internationally renowned automobile race. Certain rights were guaranteed to autochthonous Libyans (later called by

In Italian Tripolitania, the Italians made significant improvements to the physical infrastructure: The most important were the coastal road between Tripoli and

In Italian Tripolitania, the Italians made significant improvements to the physical infrastructure: The most important were the coastal road between Tripoli and

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

, that existed from 1911 to 1934. It was part of the territory conquered from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

after the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

in 1911. Italian Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

included the western northern half of Libya, with Tripoli as its main city. In 1934, it was unified with Italian Cyrenaica in the colony of Italian Libya.

History

Conquest and colonization

Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica were formed in 1911, during the conquest ofOttoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or '' Bey and Subjects of Tr ...

in the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

.

Despite a major revolt by the Arabs, the Ottoman sultan ceded Libya to the Italians by signing the 1912 Treaty of Lausanne. The Italians made extensive use of the Savari, colonial cavalry troops raised in December 1912. These units were recruited from the Arab-Berber population of Libya following the initial Italian occupation in 1911–12. The Savari, like the Spahi or mounted Libyan police, formed part of the ''Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali della Libia'' (Royal Corps of Libyan Colonial Troops).

Sheikh Sidi Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), of the Senussi, led Libyan resistance in various forms through the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. After the Italian army invaded Cyrenaica in 1913 as part of their invasion of Libya, the Senussi Order fought back against them. When the Order's leader, Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi

Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi ( ar, أحمد الشريف السنوسي) (1873 – 10 March 1933) was the supreme leader of the Senussi order (1902–1933), although his leadership in the years 1917–1933 could be considered nominal. His daughter, ...

, abdicated his position, he was replaced by Idris, who was his cousin. Pressured to do so by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, Ahmed had pursued armed attacks against British military forces stationed in neighbouring Egypt. On taking power, Idris put a stop to these attacks.

Instead he established a tacit alliance with the British, which would last for half a century and accord his Order ''de facto'' diplomatic status. Using the British as intermediaries, Idris led the Order into negotiations with the Italians in July 1916. These resulted in two agreements, at al-Zuwaytina in April 1916 and at Akrama in April 1917. The latter of these treaties left most of inland Cyrenaica under the control of the Senussi Order. Relations between the Senussi Order and the newly established Tripolitanian Republic were acrimonious. The Senussi attempted to militarily extend their power into eastern Tripolitania, resulting in a pitched battle at Bani Walid

Bani Walid (Anglicized: ; ar, بني وليد, Banī Walīd, Libyan pronunciation: ) is a city in Libya located in the Misrata District. Prior to 2007, it was the capital of Sof-Aljeen District. Bani Walid has an airport. Under the Libyan Ar ...

in which the Senussi were forced to withdraw back into Cyrenaica.

At the end of

At the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the Ottoman Empire signed an armistice agreement in which they ceded their claims over Libya to Italy. Italy however was facing serious economic, social, and political problems domestically, and was not prepared to re-launch its military activities in Libya. It issued statutes known as the ''Legge Fondamentale'' with both the Tripolitanian Republic in June 1919 and Cyrenaica in October 1919. These brought about a compromise by which all Libyans were accorded the right to a joint Libyan-Italian citizenship while each province was to have its own parliament and governing council. The Senussi were largely happy with this arrangement and Idris visited Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

as part of the celebrations to mark the promulgation of the settlement.

In October 1920, further negotiations between Italy and Cyrenaica resulted in the Accord of al-Rajma, in which Idris was given the title of the Emir of Cyrenaica and permitted to autonomously administer the oases around Kufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role ...

, Jalu, Jaghbub

Jaghbub ( ar, الجغبوب) is a remote desert village in the Al Jaghbub Oasis in the eastern Libyan Desert. It is actually closer to the Egyptian town of Siwa than to any Libyan town of note. The oasis is located in Butnan District and was th ...

, Awjila

Awjila ( Berber: ''Awilan'', ''Awjila'', ''Awgila''; ar, أوجلة; Latin: ''Augila'') is an oasis town in the Al Wahat District in the Cyrenaica region of northeastern Libya. Since classical times it has been known as a place where high quality ...

, and Ajdabiya

Ajdabiya ( ; ar, أجدابيا, Aǧdābiyā) is a town in and capital of the Al Wahat District in northeastern Libya. It is some south of Benghazi. From 2001 to 2007 it was part of and capital of the Ajdabiya District. The town is divided in ...

. As part of the Accord he was given a monthly stipend by the Italian government, who agreed to take responsibility for policing and administration of areas under Senussi control. The Accord also stipulated that Idris must fulfill the requirements of the ''Legge Fondamentale'' by disbanding the Cyrenaican military units, however he did not comply with this. By the end of 1921, relations between the Senussi Order and the Italian government had again deteriorated.

Following the death of Tripolitanian leader Ramadan Asswehly in August 1920, the Republic descended into civil war. Many tribal leaders in the region recognised that this discord was weakening the region's chances of attaining full autonomy from Italy, and in November 1920 they met in Gharyan

Gharyan is a city in northwestern Libya, in Jabal al Gharbi District, located 80 km south of Tripoli. Prior to 2007, it was the administrative seat of Gharyan District. Gharyan is one of the largest towns in the Western Mountains.

In 2005 ...

to bring an end to the violence. In January 1922 they agreed to request that Idris extend the Sanui Emirate of Cyrenaica

The Emirate of Cyrenaica ( ar, إمارة برقة) came into existence when Sayyid Idris unilaterally proclaimed Cyrenaica an independent Senussi emirate on 1 March 1949, backed by the United Kingdom. Sayyid Idris proclaimed himself Emir of C ...

into Tripolitania in order to bring stability; they presented a formal document with this request on 28 July 1922. Idris' advisers were divided on whether he should accept the offer or not. Doing so would contravene the al-Rajma Agreement and would damage relations with the Italian government, who opposed the political unification of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania as being against their interests. Nevertheless, in November 1922 Idris agreed to the proposal. Following the agreement, Idris feared that Italy — under its new Fascist leader Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

—would militarily retaliate against the Senussi Order, and so he went into exile in Egypt in December 1922.

Fighting intensified after the accession to power in Italy of the dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in time ...

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

. Due to the effective resistance of the Libyan people against Italy's so-called " pacification campaign", Italian colonization of the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

and Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

was not initially successful and it was not until the early 1930s that the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

took full control of the area.

Several reorganizations of the colonial authority had been made necessary because of armed Arab opposition, mainly in Cyrenaica. Between 1919 (17 May) to 1929 (24 January), the Italian government maintained the two traditional provinces, with separate colonial administrations. A system of controlled local assemblies with limited local authority was set up, but was revoked on 9 March 1927. In 1929, Tripoli and Cyrenaica were united as one colonial province. From 1931 to 1932, Italian forces under General Badoglio waged a punitive pacification

Extrajudicial punishment is a punishment for an alleged crime or offense which is carried out without legal process or supervision by a court or tribunal through a legal proceeding.

Politically motivated

Extrajudicial punishment is often a fea ...

campaign. Badoglio's successor in the field, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

, accepted the commission from Mussolini on the condition that he was allowed to crush Libyan resistance

The Libyan resistance movement was the rebel force opposing the Italian Empire during its Pacification of Libya between 1923 and 1932.

History First years

The Libyan resistance, associated with the Senussi Order, was initially led by Omar ...

unencumbered by the restraints of either Italian or international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

. Mussolini reportedly agreed immediately and Graziani intensified the oppression.

Some Libyans continued to defend themselves, with the strongest voices of dissent coming from the Cyrenaica. Beginning in the first days of Italian colonization, Omar Mukhtar, a Senussi sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

, organized and, for nearly twenty years, led Libyan resistance efforts. His example continued to inspire resistance even after his capture and execution on 16 September 1931. His face is currently printed on the Libyan ten dinar note in memory and recognition of his patriotism.

By 1934, Libyan indigenous resistance was effectively crushed. The new Italian governor Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

created the political entity called Italian Libya in the summer of that year. The classical name "Libya" was revived as the official name of the unified colony. Then in 1937 the colony was split administratively into four provinces: Tripoli, Misrata

Misrata ( ; also spelled Misurata or Misratah; ar, مصراتة, Miṣrāta ) is a city in the Misrata District in northwestern Libya, situated to the east of Tripoli and west of Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast near Cape Misrata. With ...

, Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη ('' Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghaz ...

, and Derna. The Fezzan area was called Territorio Sahara Libico

The Southern Military Territory ( it, Territorio Militare del Sud) refers to the jurisdictional territory within the colony of Italian Libya (1911–1947), administered by the Italian military in the Libyan Sahara.

Data

This military territory w ...

and administered militarily."

Unification with Cyrenaica

Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica were formed in 1911, during the conquest ofOttoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or '' Bey and Subjects of Tr ...

in the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

. In 1934, Italian Tripolitania became part of Italian Libya.

In December 1934, certain rights were guaranteed to autochthonous Libyans (later called by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

"Moslem Italians") including individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, the right to join the military or civil administrations, and the right to freely pursue a career or employment.

In 1937, northern Tripolitania was split into Tripoli Province

Tripoli Province (''Provincia di Tripoli'' in Italian) was one of the provinces of Libya under Italian rule. It was established in 1937, with the official name: ''Commissariato Generale Provinciale di Tripoli''. It lasted until 1947.

Characteristi ...

and Misrata Province

Misrata ( ; also spelled Misurata or Misratah; ar, مصراتة, Miṣrāta ) is a city in the Misrata District in northwestern Libya, situated to the east of Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli and west of Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast near Cape ...

. In 1939 Tripolitania was included in the 4th Shore

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

of the Kingdom of Italy.

In early 1943 the region was invaded and occupied by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

; this was the end of the Italian colonial presence.

Italy tried unsuccessfully to maintain the colony of Tripolitania after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, but in February 1947 relinquished all Italian colonies in a Peace Treaty.

Colonial administration

Provinces

The Province of Tripoli (the most important in all Italian Libya) was subdivided into: * Tripoli * Zawiya *Sugh el Giumaa *Nalut

Nalut (sometimes Lalút) ( ar, نالوت) is the capital of the Nalut District in Libya. Nalut lies approximately halfway between Tripoli and Ghadames, at the western end of the Nafusa Mountains coastal range, in the Tripolitania region.

The ...

*Gharyan

Gharyan is a city in northwestern Libya, in Jabal al Gharbi District, located 80 km south of Tripoli. Prior to 2007, it was the administrative seat of Gharyan District. Gharyan is one of the largest towns in the Western Mountains.

In 2005 ...

Demography

A large number of Italian colonists moved to Tripolitania in the late 1930s. These settlers went primarily to the area of Sahel al-Jefara, in Tripolitania, and to the capital Tripoli. In 1939 there were in all Tripolitania nearly 60,000 Italians, most living in Tripoli (whose population was nearly 45% Italian). As a consequence, huge economic improvements arose in all coastal Tripolitania. For example, Italians created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an internationally renowned automobile race. Certain rights were guaranteed to autochthonous Libyans (later called by

A large number of Italian colonists moved to Tripolitania in the late 1930s. These settlers went primarily to the area of Sahel al-Jefara, in Tripolitania, and to the capital Tripoli. In 1939 there were in all Tripolitania nearly 60,000 Italians, most living in Tripoli (whose population was nearly 45% Italian). As a consequence, huge economic improvements arose in all coastal Tripolitania. For example, Italians created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an internationally renowned automobile race. Certain rights were guaranteed to autochthonous Libyans (later called by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

"Moslem Italians") including individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, the right to join the military or civil administrations, and the right to freely pursue a career or employment.

Infrastructure

In Italian Tripolitania, the Italians made significant improvements to the physical infrastructure: The most important were the coastal road between Tripoli and

In Italian Tripolitania, the Italians made significant improvements to the physical infrastructure: The most important were the coastal road between Tripoli and Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη ('' Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghaz ...

and the railways Tripoli-Zuara, Tripoli-Garian and Tripoli-Tagiura. Other important infrastructure improvements were the enlargement of the port of Tripoli and the creation of the Tripoli airport.

A group of villages for Italians and Libyans was created on coastal Tripolitania during the 1930s.

Archaeology and tourism

Classical archaeology

Classical archaeology is the archaeological investigation of the Mediterranean civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Nineteenth-century archaeologists such as Heinrich Schliemann were drawn to study the societies they had read about i ...

was used by the Italian authorities as a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

tool to justify their presence in the region. Before 1911, no archeological research was done in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. By the late 1920s the Italian government had started funding excavations in the main Roman cities of Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was great ...

and Sabratha

Sabratha ( ar, صبراتة, Ṣabrāta; also ''Sabratah'', ''Siburata''), in the Zawiya Districtexcavation

Excavation may refer to:

* Excavation (archaeology)

* Excavation (medicine)

* ''Excavation'' (The Haxan Cloak album), 2013

* ''Excavation'' (Ben Monder album), 2000

* ''Excavation'' (novel), a 2000 novel by James Rollins

* '' Excavation: A Mem ...

policy, which exclusively benefitted Italian museums and journals.Dyson, S.L (2006). In pursuit of ancient pasts: a history of classical archaeology in the 19th and 20h centuries. pp. 182–183.

After Cyrenaica's full pacification, the Italian archaeological efforts in the 1930s were more focused on the former Greek colony of Cyrenaica than in Tripolitania, which was a Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

colony during the Greek period. The rejection of Phoenician research was partly because of anti-Semitic reasons (the Phoenicians were a Semitic people, distantly related to the Arabs and Jews). Of special interest were the Roman colonies of Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was great ...

and Sabratha

Sabratha ( ar, صبراتة, Ṣabrāta; also ''Sabratah'', ''Siburata''), in the Zawiya Districtarchaeological tourism

Archaeotourism or Archaeological tourism is a form of cultural tourism, which aims to promote public interest in archaeology and the conservation of historical sites.

Activities

Archaeological tourism can include all products associated with ...

.

Tourism was further promoted by the creation of the Tripoli Grand Prix, a racing car event of international importance.

Main military and political developments

*1911: Beginning of theItalo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

. Italian conquest of Tripoli, and Al Khums

Al-Khums or Khoms ( ar, الخمس) is a city, port and the de jure capital of the Murqub District on the Mediterranean coast of Libya with an estimated population of around 202,000. The population at the 1984 census was 38,174. Between 1983 and 19 ...

.خليفة Kalifa Tillisi, “Mu’jam Ma’arik Al Jihad fi Libia1911-1931”, Dar Ath Thaqafa, Beirut, Lebanon, 1973.

*1912: ends the Italo-Turkish war. Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

and Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

were ceded to Italy.

*1914: Italian advance to Ghat (August) makes Tripolitania (including Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

) initially under Italian suzerainty, but because of the recapture of Sabha (November) by Libyan resistance men, the advance turns into retreat.

*1915: Italian reverses at the battles of Wadi Marsit, and Al Gardabiya, forced them to withdraw and eventually to retire to Tripoli, Zuwara, and Al Khums

Al-Khums or Khoms ( ar, الخمس) is a city, port and the de jure capital of the Murqub District on the Mediterranean coast of Libya with an estimated population of around 202,000. The population at the 1984 census was 38,174. Between 1983 and 19 ...

.

*1922:Italian forces occupy Misrata

Misrata ( ; also spelled Misurata or Misratah; ar, مصراتة, Miṣrāta ) is a city in the Misrata District in northwestern Libya, situated to the east of Tripoli and west of Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast near Cape Misrata. With ...

, launching the reconquest of Tripolitania.

*1924: With the conquest of Sirt, most of Tripolitania (except the Sirt desert) is in Italian hands.

*Winter 1927-8: Launching the "29th Parallel line operations", as a result of coordination between the governments of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, led to the conquest of gulf of Sidra

The Gulf of Sidra ( ar, خليج السدرة, Khalij as-Sidra, also known as the Gulf of Sirte ( ar, خليج سرت, Khalij Surt, is a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea on the northern coast of Libya, named after the oil port of Sidra or ...

, and linking the two colonies.Attilio Teruzzi, "Cirenaica Verdi", translated by Kalifa Tillisi, ad Dar al Arabiya lil Kitab, 1991.

*1929: Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

becomes a unique governor of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica.

*1929-1930: Conquest of Fezzan.

*1934: Tripolitania is incorporated into the Colony of Libya.

*1939: Tripolitania is made part of the 4th Shore

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

of the Kingdom of Italy.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Chapin Metz, Helen, ed. ''Libya: A Country Study''. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1987. * Del Boca, Angelo. ''Gli italiani in Libia. Vol. 1: Tripoli bel suol d'Amore''. Milano, Mondadori, 1997. * Sarti, Durand. ''The Ax within: Italian Fascism in Action''. Modern Viewpoints. New York, 1974.See also

* List of colonial governors of Italian Tripolitania *Postage stamps and postal history of Tripolitania

This is a survey of the postage stamps and postal history of Tripolitania, now part of Libya.

Tripolitana is a historic region of western Libya, centered on the coastal city of Tripoli. Formerly part of the Ottoman Empire, Tripolitania wa ...

*Banknotes of the Military Authority in Tripolitania Banknotes were issued in 1943 by the British Army for circulation in Tripolitania. The main feature of the notes is depiction of a lion standing on the King's Crown. The notes are inscribed in both Arabic and English.

The currency that these note ...

* Libyan resistance movement

*Territorio Sahara Libico

The Southern Military Territory ( it, Territorio Militare del Sud) refers to the jurisdictional territory within the colony of Italian Libya (1911–1947), administered by the Italian military in the Libyan Sahara.

Data

This military territory w ...

* Italian Libya Railways

*4th Shore

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

{{coord missing, Libya

History of Tripolitania

Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

States and territories established in 1911

States and territories disestablished in 1934

Former countries in Africa

Italy–Libya relations

1911 establishments in Africa

1934 disestablishments in Africa

1911 establishments in the Italian Empire

1934 disestablishments in the Italian Empire

Former countries of the interwar period