Italian North Africa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in

After the

After the

In 1923, indigenous rebels associated with the

In 1923, indigenous rebels associated with the

The colony expanded after concessions from the British colony of

The colony expanded after concessions from the British colony of

After the enlargement of Italian Libya with the

After the enlargement of Italian Libya with the  Starting in December of the same year, the British Eighth Army launched a

Starting in December of the same year, the British Eighth Army launched a  With German support, the lost Libyan territory was regained during

With German support, the lost Libyan territory was regained during

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). The colony was subdivided into four provincial governatores (''Commissariato Generale Provinciale'') and a southern military territory (''Territorio Militare del Sud'' or ''Territorio del Sahara Libico''):Rodogno, D. (2006). Fascism's European empire:

Italian occupation during the Second World War. p. 61.

*

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). The colony was subdivided into four provincial governatores (''Commissariato Generale Provinciale'') and a southern military territory (''Territorio Militare del Sud'' or ''Territorio del Sahara Libico''):Rodogno, D. (2006). Fascism's European empire:

Italian occupation during the Second World War. p. 61.

*

In 1939, key population figures for Italian Libya were as follows:

Population of the main urban centres:

In 1939, key population figures for Italian Libya were as follows:

Population of the main urban centres:

Many Italians were encouraged to settle in Libya during the Fascist period, notably in the coastal areas. The annexation of Libya's coastal provinces in 1939 brought them to be an integral part of metropolitan Italy and the focus of Italian settlement.Jon Wright. History of Libya. P. 165.

The population of Italian settlers in Libya increased rapidly after the Great Depression: in 1927, there were just about 26,000, by 1931 44,600, 66,525 in 1936 and eventually, in 1939, they numbered 119,139, or 13% of the total population.

They were concentrated on the Mediterranean coast, especially in the main urban centres and in the farmlands around Tripoli, where they constituted 41% of the city's population, and in Benghazi 35%. Settlers found jobs in the construction boom fuelled by Fascist interventionist policies.

In 1938, Governor

Many Italians were encouraged to settle in Libya during the Fascist period, notably in the coastal areas. The annexation of Libya's coastal provinces in 1939 brought them to be an integral part of metropolitan Italy and the focus of Italian settlement.Jon Wright. History of Libya. P. 165.

The population of Italian settlers in Libya increased rapidly after the Great Depression: in 1927, there were just about 26,000, by 1931 44,600, 66,525 in 1936 and eventually, in 1939, they numbered 119,139, or 13% of the total population.

They were concentrated on the Mediterranean coast, especially in the main urban centres and in the farmlands around Tripoli, where they constituted 41% of the city's population, and in Benghazi 35%. Settlers found jobs in the construction boom fuelled by Fascist interventionist policies.

In 1938, Governor

After the campaign of reprisals known as the "pacification campaign", the Italian government changed policy toward the local population: in December 1934, individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, the right to join the military or civil administrations, and the right to freely pursue a career or employment were promised to the Libyans.

In a trip by Mussolini to Libya in 1937, a propaganda event was created where Mussolini met with

After the campaign of reprisals known as the "pacification campaign", the Italian government changed policy toward the local population: in December 1934, individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, the right to join the military or civil administrations, and the right to freely pursue a career or employment were promised to the Libyans.

In a trip by Mussolini to Libya in 1937, a propaganda event was created where Mussolini met with

Italians greatly developed the two main cities of Libya, Tripoli and Benghazi, with new ports and airports, new hospitals and schools and many new roads & buildings.

Italians greatly developed the two main cities of Libya, Tripoli and Benghazi, with new ports and airports, new hospitals and schools and many new roads & buildings.

Also tourism was improved and a huge & modern "Grand Hotel" was built in Tripoli and in Bengasi.

The Fascist regime, especially during Depression years, emphasized

Also tourism was improved and a huge & modern "Grand Hotel" was built in Tripoli and in Bengasi.

The Fascist regime, especially during Depression years, emphasized

After independence, most Italian settlers still remained in Libya; there were 35,000 Italo-Libyans in 1962. However, the Italian population virtually disappeared after the Libyan leader

After independence, most Italian settlers still remained in Libya; there were 35,000 Italo-Libyans in 1962. However, the Italian population virtually disappeared after the Libyan leader  On 30 August 2008, Gaddafi and Italian

On 30 August 2008, Gaddafi and Italian

Photos of Libyan Italians and their villages in Libya

*

Italian colonial railways built in Libya

*

Italian Tripolitania in early 1930s

{{coord missing, Libya

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, in what is now modern Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania

Italian Tripolitania was an Italian colony, located in present-day western Libya, that existed from 1911 to 1934. It was part of the territory conquered from the Ottoman Empire after the Italo-Turkish War in 1911. Italian Tripolitania included t ...

, which had been Italian possessions since 1911.

From 1911 until the establishment of a unified colony in 1934, the territory of the two colonies was sometimes referred to as "Italian Libya" or Italian North Africa (''Africa Settentrionale Italiana'', or ASI). Both names were also used after the unification, with Italian Libya becoming the official name of the newly combined colony. It had a population of around 150,000 Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

.

The Italian colonies of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were taken by Italy from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

during the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

of 1911-1912, and run by Italian governors. In 1923, indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

Order organized the Libyan resistance movement against Italian settlement in Libya, mainly in Cyrenaica. The rebellion was put down by Italian forces in 1932, after the so-called " pacification campaign", which resulted in the deaths of a quarter of Cyrenaica's population. In 1934, the colonies were unified by governor Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

, with Tripoli as the capital.

During World War II, Italian Libya became the setting for the North African Campaign. Although the Italians were defeated there by the Allies in 1943, many of the Italian settlers still remained in Libya. Libya was administered by the United Kingdom and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

until its independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the stat ...

in 1951, though Italy did not officially relinquish its claim until the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty.

History

Conquest

Italian efforts to colonize Libya began in 1911, and were characterized initially by major struggles with Muslim native Libyans that lasted until 1931. During this period, the Italian government controlled only the coastal areas. Between 1911 and 1912, over 1,000 Somalis fromMogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port ...

, the then capital of Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centu ...

, served in combat units along with Eritrean and Italian soldiers in the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

. Most of the Somali troops remained in Libya until they were transferred back to Italian Somaliland in preparation for the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

After the

After the Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependenci ...

's conquest of Ottoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or '' Bey and Subjects of Tr ...

(Ottoman Libya), in the 1911–12 Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

, much of the early colonial period had Italy waging a war of subjugation against Libya's population. Ottoman Turkey surrendered its control of Libya in the 1912 Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the confl ...

, but fierce resistance to the Italians continued from the Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

political-religious order, a strongly nationalistic group of Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagre ...

s. This group, first under the leadership of Omar Al Mukhtar

Omar al-Mukhṭār Muḥammad bin Farḥāṭ al-Manifī ( ar, عُمَر الْمُخْتَار مُحَمَّد بِن فَرْحَات الْمَنِفِي ; 20 August 1858 – 16 September 1931), called The Lion of the Desert, known among ...

and centered in the Jebel Akhdar Mountains of Cyrenaica, led the Libyan resistance movement against Italian settlement in Libya. Italian forces under Generals Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

and Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

waged punitive pacification campaigns using chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

, mass executions of soldiers and civilians and concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

. One-quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000 people died during the conflict. After nearly two decades of suppression campaigns the Italian colonial forces claimed victory.

In the 1930s, the policy of Italian Fascism toward Libya began to change, and both Italian Cyrenaica and Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

, along with Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

, were merged into Italian Libya in 1934.

Pacification campaigns

In 1923, indigenous rebels associated with the

In 1923, indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

Order organized the Libyan resistance movement against Italian settlement in Libya. The rebellion was put down by Italian forces in 1932, after the so-called " pacification campaign", which resulted in the deaths of a quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000. Italy committed major war crimes during the conflict, including the use of illegal chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

s, episodes of refusing to take prisoners of war and instead executing surrendering combatants, and mass executions of civilians. Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

by forcibly expelling 100,000 Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

Cyrenaicans, almost half the population of Cyrenaica, from their settlements, slated to be given to Italian settlers.

The Italian occupation also reduced livestock numbers, killing, confiscating or driving the animals from their pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depict ...

land to inhospitable land near the concentration camps.General History of Africa, Albert Adu Boahen, Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, page 196, 1990 The number of sheep fell from 810,000 in 1926 to 98,000 in 1933, goats from 70,000 to 25,000 and camels from 75,000 to 2,000.

From 1930 to 1931, 12,000 Cyrenaicans were executed and all the nomadic peoples of northern Cyrenaica were forcibly removed from the region and relocated to huge concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s in the Cyrenaican lowlands. Fascist regime propaganda proclaimed the camps as hygienic and efficiently run oases of modern civilization. However in reality the camps had poor sanitary conditions and an average of about 20,000 Beduoins, together with their camels and other animals, crowded into an area of one square kilometre. The camps held only rudimentary medical services, with the camps of Soluch and Sisi Ahmed el Magrun with an estimated 33,000 internees having only one doctor between them. Typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

and other diseases spread rapidly in the camps as the people were physically weakened by meagre food rations and forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. By the time the camps closed in September 1933, 40,000 of the 100,000 total internees had died in the camps.

Territorial agreements with European powers

Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and a territorial agreement with Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. The Kufra district

Kufra or Kofra ( ar, الكفرة '), also spelled ''Cufra'' in Italian, is the largest district of Libya. Its capital is Al Jawf, one of the oases in Kufra basin. There is a very large oil refinery near the capital. In the late 15th century, ...

was nominally attached to British-occupied Egypt until 1925, but in fact, remained a headquarters for the Senussi resistance until conquered by the Italians in 1931. The Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

at the 1919 Paris "Conference of Peace" received nothing from German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

colonies, but as a compensation Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

gave it the Oltre Giuba

Oltre Giuba or Trans-Juba ( ar, شرق جوبا الإيطالية) was an Italian colony in the territory of Jubaland in present-day southern Somalia. It lasted for one year, from 1924 until 1925, when it was absorbed into Italian Somaliland. '' ...

and France agreed to give some Saharan territories to Italian Libya.

After prolonged discussions through the 1920s, in 1935 under the Mussolini-Laval agreement Italy received the Aouzou strip

The Aouzou Strip (; ar, قطاع أوزو, Qiṭāʿ Awzū, french: Bande d'Aozou) is a strip of land in northern Chad that lies along the border with Libya, extending south to a depth of about 100 kilometers into Chad's Borkou, Ennedi Ouest ...

, which was added to Libya. However, this agreement was not ratified later by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

In 1931, the towns of El Tag

El Tag (; also ''Al-Tag'', ''Al-Taj'') is a village and holy site in the Kufra Oasis, within the Libyan Desert subregion of the Sahara. It is in the Kufra District in the southern Cyrenaica region of southeastern Libya. The Arabic ''el tag'' trans ...

and Al Jawf were taken over by Italy. British Egypt had ceded Kufra and Jarabub to Italian Libya on December 6, 1925, but it was not until the early 1930s that Italy was in full control of the place. In 1931, during the campaign of Cyrenaica, General Rodolfo Graziani easily conquered Kufra District, considered a strategic region, leading about 3,000 soldiers from infantry and artillery, supported by about twenty bombers. Ma'tan as-Sarra

Ma'tan as-Sarra is an oasis in the Kufra District municipality in the southeast corner of Libya. It is located in the Libyan Desert, southwest of Kufra. A marginal oasis, with few palms and substandard water, it allowed the creation in 1811 of ...

was turned over to Italy in 1934 as part of the Sarra Triangle

The Sarra Triangle is a strip of land, today located in the Kufra District of Libya, originally colonised by Britain and added to Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. In 1934 an agreement was struck between the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Italy, ceding the ...

to colonial Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

by the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, who considered the area worthless and so an act of cheap appeasement to Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's attempts at an empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

.Burr, J. Millard and Robert O. Collins, ''Darfur: The Long Road to Disaster'', Markus Wiener Publishers: Princeton, 2006, , p. 111 During this time, the Italian colonial forces built a World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

–style fort in El Tag in the mid-1930s.

World War II

After the enlargement of Italian Libya with the

After the enlargement of Italian Libya with the Aouzou Strip

The Aouzou Strip (; ar, قطاع أوزو, Qiṭāʿ Awzū, french: Bande d'Aozou) is a strip of land in northern Chad that lies along the border with Libya, extending south to a depth of about 100 kilometers into Chad's Borkou, Ennedi Ouest ...

, Fascist Italy aimed at further extension to the south. Indeed Italian plans, in the case of a war against France and Great Britain, projected the extension of Libya as far south as Lake Chad

Lake Chad (french: Lac Tchad) is a historically large, shallow, endorheic lake in Central Africa, which has varied in size over the centuries. According to the ''Global Resource Information Database'' of the United Nations Environment Programme ...

and the establishment of a broad land bridge between Libya and Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the S ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, there was strong support for Italy from many Muslim Libyans, who enrolled in the Italian Army

"The safeguard of the republic shall be the supreme law"

, colors =

, colors_labels =

, march = ''Parata d'Eroi'' ("Heroes's parade") by Francesco Pellegrino, ''4 Maggio'' (May 4) ...

. Other Libyan troops (the Savari avalry regimentsand the Spahi

Spahis () were light-cavalry regiments of the French army recruited primarily from the indigenous populations of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. The modern French Army retains one regiment of Spahis as an armoured unit, with personnel now ...

or mounted police) had been fighting for the Kingdom of Italy since the 1920s. A number of major battles took place in Libya during the North African Campaign of World War II. In September 1940, the Italian invasion of Egypt

The Italian invasion of Egypt () was an offensive in the Second World War, against British, Commonwealth and Free French forces in the Kingdom of Egypt. The invasion by the Italian 10th Army () ended border skirmishing on the frontier and ...

was launched from Libya.

Starting in December of the same year, the British Eighth Army launched a

Starting in December of the same year, the British Eighth Army launched a counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

called Operation Compass

Operation Compass (also it, Battaglia della Marmarica) was the first large British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) during the Second World War. British, Empire and Commonwealth forces attacked Italian forces of ...

and the Italian forces were pushed back into Libya. After losing all of Cyrenaica and almost all of its Tenth Army, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

asked for German assistance to aid the failing campaign

With German support, the lost Libyan territory was regained during

With German support, the lost Libyan territory was regained during Operation Sonnenblume

Operation Sonnenblume (/Operation Sunflower) was the name given to the dispatch of German troops to North Africa in February 1941, during the Second World War. The Italian 10th Army () had been destroyed by the British, Commonwealth, Empire and ...

and by the conclusion of Operation Brevity

Operation Brevity was a limited offensive conducted in mid-May 1941, during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War. Conceived by the commander-in-chief of the British Middle East Command, General Archibald Wavell, Brevity was inte ...

, German and Italian forces were entering Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. The first Siege of Tobruk

The siege of Tobruk lasted for 241 days in 1941, after Axis forces advanced through Cyrenaica from El Agheila in Operation Sonnenblume against Allied forces in Libya, during the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) of the Second World ...

in April 1941 marked the first failure of Rommel's Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air ...

tactics. In 1942 there was the Battle of Gazala

The Battle of Gazala (near the village of ) was fought during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War, west of the port of Tobruk in Libya, from 26 May to 21 June 1942. Axis troops of the ( Erwin Rommel) consisting of German an ...

when the Axis troops finally conquered Tobruk and pushed the defeated British troops inside Egypt again. Defeat during the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa had prevented th ...

in Egypt spelled doom for the Axis forces in Libya and meant the end of the Western Desert Campaign.

In February 1943, retreating German and Italian forces were forced to abandon Libya as they were pushed out of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, thus ending Italian jurisdiction and control over Libya.

The Fezzan was occupied by the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

in 1943. At the close of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

collaborated with the small new resistance. France and the United Kingdom decided to make King Idris

Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi ( ar, إدريس, Idrīs; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was a Libyan political and religious leader who was King of Libya from 24 December 1951 until his overthrow on 1 September 1969. He ruled o ...

the Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

of an independent Libya in 1951.

Libya would finally become independent in 1951.

Independence

From 1943 to 1951, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British military administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya. There were discussions to maintain the province of Tripolitania as the last Italian colony, but these were not successful. Although Britain and France had intended to dividing the nation between their empires, on November 21, 1949, theUN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya

The Kingdom of Libya ( ar, المملكة الليبية, lit=Libyan Kingdom, translit=Al-Mamlakah Al-Lībiyya; it, Regno di Libia), known as the United Kingdom of Libya from 1951 to 1963, was a constitutional monarchy in North Africa which c ...

, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy.

Colonial administration

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). The colony was subdivided into four provincial governatores (''Commissariato Generale Provinciale'') and a southern military territory (''Territorio Militare del Sud'' or ''Territorio del Sahara Libico''):Rodogno, D. (2006). Fascism's European empire:

Italian occupation during the Second World War. p. 61.

*

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). The colony was subdivided into four provincial governatores (''Commissariato Generale Provinciale'') and a southern military territory (''Territorio Militare del Sud'' or ''Territorio del Sahara Libico''):Rodogno, D. (2006). Fascism's European empire:

Italian occupation during the Second World War. p. 61.

*Tripoli Province

Tripoli Province (''Provincia di Tripoli'' in Italian) was one of the provinces of Libya under Italian rule. It was established in 1937, with the official name: ''Commissariato Generale Provinciale di Tripoli''. It lasted until 1947.

Characteristi ...

, capital Tripoli.

*Benghazi Province

Benghazi Province, or ''Provincia di Bengasi'' in Italian, was one of the provinces of Libya under Italian rule. It was established in 1937.

Characteristics

Benghazi Province was located in northern Italian Libya, in western Cyrenaica. Its admin ...

, capital Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη ('' Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghaz ...

.

*Darnah Province

Darnah Province (called in Italian ''Provincia italiana di Derna'') was one of the provinces of Libya under Italian rule. It was established in 1937 with the official name: "Commissariato Generale Provinciale di Derna". Derna province was called ...

, capital Derna.

*Misurata Province

Misrata ( ar, مصراته , Libyan Arabic: ''Məṣrātah''), also spelt ''Misurata'' or ''Misratah'', is a sha'biyah (district) in northwestern Libya. Its capital is the city of Misrata. In 2007 the district was enlarged to include what had bee ...

, capital Misrata

Misrata ( ; also spelled Misurata or Misratah; ar, مصراتة, Miṣrāta ) is a city in the Misrata District in northwestern Libya, situated to the east of Tripoli and west of Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast near Cape Misrata. With ...

.

*Southern Military Territory

The Southern Military Territory ( it, Territorio Militare del Sud) refers to the jurisdictional territory within the colony of Italian Libya (1911–1947), administered by the Italian military in the Libyan Sahara.

Data

This military territory w ...

, capital Hun

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

The general provincial commissionerships were further divided into wards (''circondari''). On 9 January 1939, a decree law transformed the commissariats into provinces within the metropolitan territory of the Kingdom of Italy. Libya was thus formally annexed to Italy and the coastal area was nicknamed the " Fourth Shore" (''Quarta Sponda''). Key towns and wards of the colony became Italian municipalities (''comune

The (; plural: ) is a local administrative division of Italy, roughly equivalent to a township or municipality. It is the third-level administrative division of Italy, after regions ('' regioni'') and provinces (''province''). The can also ...

'') governed by a ''podestà

Podestà (, English: Potestate, Podesta) was the name given to the holder of the highest civil office in the government of the cities of Central and Northern Italy during the Late Middle Ages. Sometimes, it meant the chief magistrate of a city ...

''.

Governors-General of Libya

*Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

1 January 1934 to 28 June 1940

*Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

1 July 1940 to 25 March 1941

*Italo Gariboldi

Italo Gariboldi (20 April 1879 – 3 February 1970) was an Italian senior officer in the Royal Army (''Regio Esercito'') before and during World War II. He was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross by German dictator Adolf Hitler for hi ...

25 March 1941 to 19 July 1941

*Ettore Bastico

Ettore Bastico (9 April 1876 – 2 December 1972) was an Italian military officer before and during World War II. In addition to being a general of the Royal Italian Army, he was also a senator and governor. He held high commands during the Se ...

19 July 1941 to 2 February 1943

*Giovanni Messe

Giovanni Messe (10 December 1883 – 18 December 1968) was an Italian field marshal and politician. In the Second World War, he was captured in Tunisia, but made chief of staff of the Italian Co-belligerent Army after the armistice of Septemb ...

2 February 1943 to 13 May 1943

Demographics

In 1939, key population figures for Italian Libya were as follows:

Population of the main urban centres:

In 1939, key population figures for Italian Libya were as follows:

Population of the main urban centres:

Settler colonialism

Many Italians were encouraged to settle in Libya during the Fascist period, notably in the coastal areas. The annexation of Libya's coastal provinces in 1939 brought them to be an integral part of metropolitan Italy and the focus of Italian settlement.Jon Wright. History of Libya. P. 165.

The population of Italian settlers in Libya increased rapidly after the Great Depression: in 1927, there were just about 26,000, by 1931 44,600, 66,525 in 1936 and eventually, in 1939, they numbered 119,139, or 13% of the total population.

They were concentrated on the Mediterranean coast, especially in the main urban centres and in the farmlands around Tripoli, where they constituted 41% of the city's population, and in Benghazi 35%. Settlers found jobs in the construction boom fuelled by Fascist interventionist policies.

In 1938, Governor

Many Italians were encouraged to settle in Libya during the Fascist period, notably in the coastal areas. The annexation of Libya's coastal provinces in 1939 brought them to be an integral part of metropolitan Italy and the focus of Italian settlement.Jon Wright. History of Libya. P. 165.

The population of Italian settlers in Libya increased rapidly after the Great Depression: in 1927, there were just about 26,000, by 1931 44,600, 66,525 in 1936 and eventually, in 1939, they numbered 119,139, or 13% of the total population.

They were concentrated on the Mediterranean coast, especially in the main urban centres and in the farmlands around Tripoli, where they constituted 41% of the city's population, and in Benghazi 35%. Settlers found jobs in the construction boom fuelled by Fascist interventionist policies.

In 1938, Governor Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

brought 20,000 Italian farmers to settle in Libya, and 27 new villages were founded, mainly in Cyrenaica.

Assimilation policies

After the campaign of reprisals known as the "pacification campaign", the Italian government changed policy toward the local population: in December 1934, individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, the right to join the military or civil administrations, and the right to freely pursue a career or employment were promised to the Libyans.

In a trip by Mussolini to Libya in 1937, a propaganda event was created where Mussolini met with

After the campaign of reprisals known as the "pacification campaign", the Italian government changed policy toward the local population: in December 1934, individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, the right to join the military or civil administrations, and the right to freely pursue a career or employment were promised to the Libyans.

In a trip by Mussolini to Libya in 1937, a propaganda event was created where Mussolini met with Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

dignitaries, who gave him an honorary sword (that had actually been made in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

) which was to symbolize Mussolini as a protector of the Muslim Arab peoples there.

In January 1939, Italy annexed territories in Libya that it considered Italy's Fourth Shore with Libya's four coastal provinces of Tripoli, Misurata, Bengazi, and Derna becoming an integral part of metropolitan Italy. At the same time indigenous Libyans were granted "Special Italian Citizenship" which required such people to be literate and confined this type of citizenship to be valid in Libya only.

In 1939, laws were passed that allowed Muslims to be permitted to join the National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

and in particular the Muslim Association of the Lictor (''Associazione Musulmana del Littorio''). This allowed the creation of Libyan military units within the Italian army. In March 1940, two divisions of Libyan colonial troops (for a total of 30,090 native Muslim soldiers) were created and in summer 1940 the first and second Divisions of ''Fanteria Libica'' (Libyan infantry) participated in the Italian offensive against the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

's Egypt: 1st Libyan Division and 2nd Libyan Division.

Economy

In 1936, the main sectors of economic activity in Italian Libya (by number of employees) were industry (30.4%), public administration (29.8%), agriculture and fishing (16.7%), commerce (10.7%), transports (5.8%), domestic work (3.8%), legal profession and private teaching (1.3%), banking and insurance (1.1%).Infrastructure development

Italians greatly developed the two main cities of Libya, Tripoli and Benghazi, with new ports and airports, new hospitals and schools and many new roads & buildings.

Italians greatly developed the two main cities of Libya, Tripoli and Benghazi, with new ports and airports, new hospitals and schools and many new roads & buildings.

Also tourism was improved and a huge & modern "Grand Hotel" was built in Tripoli and in Bengasi.

The Fascist regime, especially during Depression years, emphasized

Also tourism was improved and a huge & modern "Grand Hotel" was built in Tripoli and in Bengasi.

The Fascist regime, especially during Depression years, emphasized infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

improvements and public works. In particular, Governor Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

greatly expanded Libyan railway and road networks from 1934 to 1940, building hundreds of kilometers of new roads and railways and encouraging the establishment of new industries and a dozen new agricultural villages. The massive Italian investment did little to improve Libyan quality of life, since the purpose was to develop the economy for the benefit of Italy and Italian settlers.

The Italian aim was to drive the local population to the marginal land in the interior and to resettle the Italian population in the most fertile lands of Libya.

The Italians did provide the Libyans with some initial education but minimally improved native administration. The Italian population (about 10% of the total population) had 81 elementary schools in 1939–1940, while the Libyans (more than 85% of total population) had 97.

There were only three secondary schools for Libyans by 1940, two in Tripoli and one in Benghazi.

The Libyan economy substantially grew in the late 1930s, mainly in the agricultural sector. Even some manufacturing activities were developed, mostly related to the food industry. Building construction increased immensely. Furthermore, the Italians made modern medical care available for the first time in Libya and improved sanitary conditions in the towns.

By 1939, the Italians had built of new railroads and of new roads. The most important and largest highway project was the Via Balbia

Via or VIA may refer to the following:

Science and technology

* MOS Technology 6522, Versatile Interface Adapter

* ''Via'' (moth), a genus of moths in the family Noctuidae

* Via (electronics), a through-connection

* VIA Technologies, a Tai ...

, an east-west coastal route connecting Tripoli in western Italian Tripolitania to Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near ...

in eastern Italian Cyrenaica. The last railway development in Libya done by the Italians was the Tripoli-Benghazi line that was started in 1941 and was never completed because of the Italian defeat during World War II.

Archaeology and tourism

Classical archaeology

Classical archaeology is the archaeological investigation of the Mediterranean civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Nineteenth-century archaeologists such as Heinrich Schliemann were drawn to study the societies they had read about i ...

was used by the Italian authorities as a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

tool to justify their presence in the region. Before 1911, no archeological research was done in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. By the late 1920s the Italian government had started funding excavations in the main Roman cities of Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was great ...

and Sabratha

Sabratha ( ar, صبراتة, Ṣabrāta; also ''Sabratah'', ''Siburata''), in the Zawiya Districtexcavation

Excavation may refer to:

* Excavation (archaeology)

* Excavation (medicine)

* ''Excavation'' (The Haxan Cloak album), 2013

* ''Excavation'' (Ben Monder album), 2000

* ''Excavation'' (novel), a 2000 novel by James Rollins

* '' Excavation: A Mem ...

policy, which exclusively benefitted Italian museums and journals.Dyson, S.L (2006). In pursuit of ancient pasts: a history of classical archaeology in the 19th and 20h centuries. pp. 182–183.

After Cyrenaica's full 'pacification', the Italian archaeological efforts in the 1930s were more focused on the former Greek colony of Cyrenaica than in Tripolitania, which was a Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

colony during the Greek period. The rejection of Phoenician research was partly because of anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

reasons (the Phoenicians were a Semitic people, distantly related to the Arabs and Jews). Of special interest were the Roman colonies of Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was great ...

and Sabratha

Sabratha ( ar, صبراتة, Ṣabrāta; also ''Sabratah'', ''Siburata''), in the Zawiya Districtarchaeological tourism

Archaeotourism or Archaeological tourism is a form of cultural tourism, which aims to promote public interest in archaeology and the conservation of historical sites.

Activities

Archaeological tourism can include all products associated with ...

.

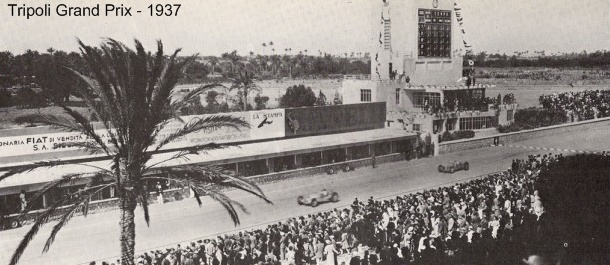

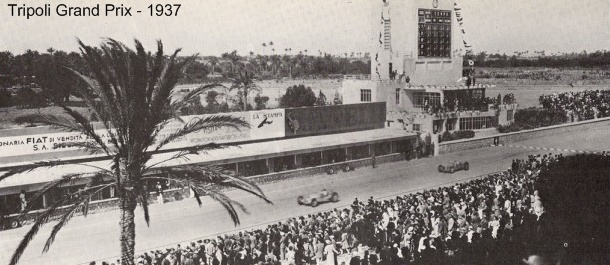

Tourism was further promoted by the creation of the Tripoli Grand Prix

The Tripoli Grand Prix (Italian: ''Gran Premio di Tripoli'') was a motor racing event first held in 1925 on a racing circuit outside Tripoli, the capital of what was then Italian Tripolitania, now Libya. It lasted until 1940.

Background

Motor ...

, a racing car event of international importance.

Contemporary relations

After independence, most Italian settlers still remained in Libya; there were 35,000 Italo-Libyans in 1962. However, the Italian population virtually disappeared after the Libyan leader

After independence, most Italian settlers still remained in Libya; there were 35,000 Italo-Libyans in 1962. However, the Italian population virtually disappeared after the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by '' The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

ordered the expulsion of remaining Italians (about 20,000) in 1970. Only a few hundred of them were allowed to return to Libya in the 2000s. In 2004, there were 22,530 Italians in Libya.

Italy maintained diplomatic relations with Libya and imported a significant quantity of its oil from the country. Relations between Italy and Libya warmed in the first decade of the 21st century, when they entered co-operative arrangements to deal with illegal immigration into Italy. Libya agreed to aggressively prevent migrants from sub-Saharan Africa from using the country as a transit route to Italy, in return for foreign aid and Italy's successful attempts to have the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

lift its trade sanctions on Libya.

On 30 August 2008, Gaddafi and Italian

On 30 August 2008, Gaddafi and Italian Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies f ...

signed a historic cooperation

Cooperation (written as co-operation in British English) is the process of groups of organisms working or acting together for common, mutual, or some underlying benefit, as opposed to working in competition for selfish benefit. Many animal a ...

treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal per ...

in Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη ('' Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghaz ...

.(in Italian) Under its terms, Italy would pay $5 billion to Libya as compensation for its former military occupation. In exchange, Libya would take measures to combat illegal immigration

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of the immigration laws of that country or the continued residence without the legal right to live in that country. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upwar ...

coming from its shores and boost investment

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing is ...

s in Italian companies. The treaty was ratified by Italy on 6 February 2009, and by Libya on 2 March, during a visit to Tripoli by Berlusconi. Cooperation ended in February 2011 as a result of the Libyan Civil War

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, and religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. The ...

which overthrew Gaddafi. At the signing ceremony of the document, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi recognized historic atrocities and repression committed by the state of Italy against the Libyan people during colonial rule, stating: "''In this historic document, Italy apologizes for its killing, destruction and repression of the Libyan people during the period of colonial rule.''" and went on to say that this was a "complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era".The Report: Libya 2008. Oxford Business Group, 2008.Pp. 17.

See also

* List of governors-general of Italian Libya *Italian invasion of Libya

The Italian invasion of Libya occurred in 1911, when Italian troops invaded the Turkish province of Libya (then part of the Ottoman Empire) and started the Italo-Turkish War. As result, Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica were establish ...

* Italian Libya Railways

Italian Libya Railways was a group of small railways built in the Italian colony of Libya between the two World Wars.

History

The Kingdom of Italy built in Italian Libya nearly 400 km of railways with gauge.

Projects

The Italian authorit ...

* Tripoli Grand Prix

The Tripoli Grand Prix (Italian: ''Gran Premio di Tripoli'') was a motor racing event first held in 1925 on a racing circuit outside Tripoli, the capital of what was then Italian Tripolitania, now Libya. It lasted until 1940.

Background

Motor ...

* Frontier Wire (Libya)

The Frontier Wire was a obstacle in Italian Libya, along the length of the border of British-held Egypt, running from El Ramleh, in the Gulf of Sollum (between Bardia and Sollum) south to Jaghbub parallel to the 25th meridian east, the Libya ...

* Italian Libyan

Italian settlers in Libya ( it, Italo-libici, also called Italian Libyans) typically refers to Italians and their descendants, who resided or were born in Libya during the Italian colonial period.

History

Italian heritage in Libya can be dat ...

s

* Massacres during the Italo-Turkish War

* Aozou Strip

The Aouzou Strip (; ar, قطاع أوزو, Qiṭāʿ Awzū, french: Bande d'Aozou) is a strip of land in northern Chad that lies along the border with Libya, extending south to a depth of about 100 kilometers into Chad's Borkou, Ennedi Ouest ...

* Italian Libyan Colonial Division

* 1st Libyan Division Sibelle

The 1st Libyan Division ( it, 1ª Divisione libica) was an infantry division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. It was commanded by general Luigi Sibille. The division took part in the Italian invasion of Egypt and was destroyed duri ...

* 2 Libyan Division Pescatori

* Savari

* Spahis

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * Chapin Metz, Helen, ed., ''Libya: A Country Study''. Washington: GPO for theLibrary of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

, 1987.

* Del Boca, Angelo. ''Gli italiani in Libia. Vol. 2''. Milano, Mondadori, 1997.

* Sarti, Roland. ''The Ax Within: Italian Fascism in Action''. Modern Viewpoints. New York, 1974.

* Smeaton Munro, Ion. ''Through Fascism to World Power: A History of the Revolution in Italy''. Ayer Publishing. Manchester (New Hampshire), 1971.

* Tuccimei, Ercole. ''La Banca d'Italia in Africa'', Foreword by Arnaldo Mauri, Collana storica della Banca d'Italia, Laterza, Bari, 1999.

* Taylor, Blaine. ''Fascist Eagle: Italy's Air Marshal Italo Balbo''. Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1996.

External links

Photos of Libyan Italians and their villages in Libya

*

Italian colonial railways built in Libya

*

Italian Tripolitania in early 1930s

{{coord missing, Libya

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

Former Italian-speaking countries

World War II occupied territories

Former colonies in Africa

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

1910s in Libya

1920s in Libya

1930s in Libya

1940s in Libya

Italy–Libya relations

1911 establishments in Africa

1943 disestablishments in Africa

Client states of Fascist Italy

Former countries of the interwar period