Israel Greene on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Israel Greene (June 17, 1824 – May 25, 1909) was a member of the

On Sunday, October 16, 1859,

On Sunday, October 16, 1859,

United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through c ...

and the leader of the company of Marines that captured John Brown during his raid on Harpers Ferry. He later left the USMC and served as an officer in the Confederate States Marine Corps

The Confederate States Marine Corps (CSMC), also referred to as the Confederate States Marines, was a branch of the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. It was established by an act of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate State ...

during the American Civil War.

Early life and education

Greene was born inPlattsburgh, New York

Plattsburgh ( moh, Tsi ietsénhtha) is a city in, and the seat of, Clinton County, New York, United States, situated on the north-western shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 19,841 at the 2020 census. The population of the surrounding ...

. He grew up in Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michi ...

and later married a woman from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

.

Career

Marine Corps

Greene joined the United States Marine Corps. He was commissioned a second lieutenant on March 3, 1847. In 1857, Greene, who advocated that Marines become artillerists, was sent toWest Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

to receive training as an artillerist. Afterward he returned to Washington to instruct Marines at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrativ ...

. In April 1859, Greene became the commander of the Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C.

Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C. is located at the corner of 8th and I Streets, Southeast in Washington, D.C. Established in 1801, it is a National Historic Landmark, the oldest post in the United States Marine Corps, the official residence of ...

and served as commander for two months. In November 1860, he led a detachment of Marines who accompanied the first Japanese diplomats to visit the United States on their return trip, on board the USS ''Niagara''.

John Brown's raid

On Sunday, October 16, 1859,

On Sunday, October 16, 1859, abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

John Brown and a group of 21 men captured the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia). On orders from President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buch ...

asked the Navy Department for a unit of Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

from the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrativ ...

, the nearest troops. First Lieutenant Greene was ordered to take a force of 86 Marines to the town. At 3:30 in the afternoon of Monday the 17th, Greene and the Marines proceeded to Harpers Ferry via the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

, they even brought two 12-pounder Dahlgren gun

Dahlgren guns were muzzle-loading naval artillery designed by Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren USN (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870), mostly used in the period of the American Civil War. Dahlgren's design philosophy evolved from an accidental ...

s (though they were left on the train and not used). At 10:00 that evening, they were met by Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

, who was the commander of the expedition. The night they surrounded the engine house, where Brown and his followers as well as nine hostages were barricaded.

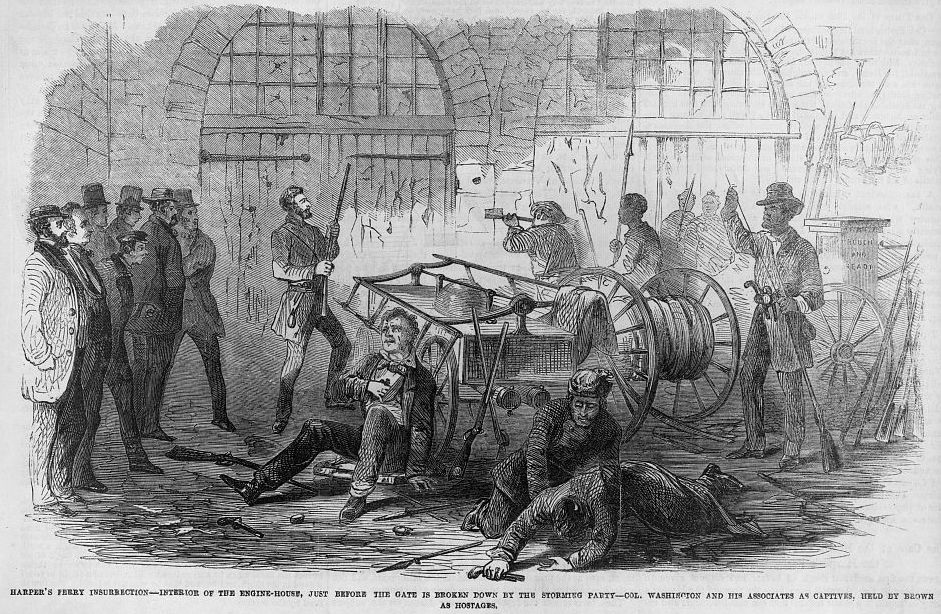

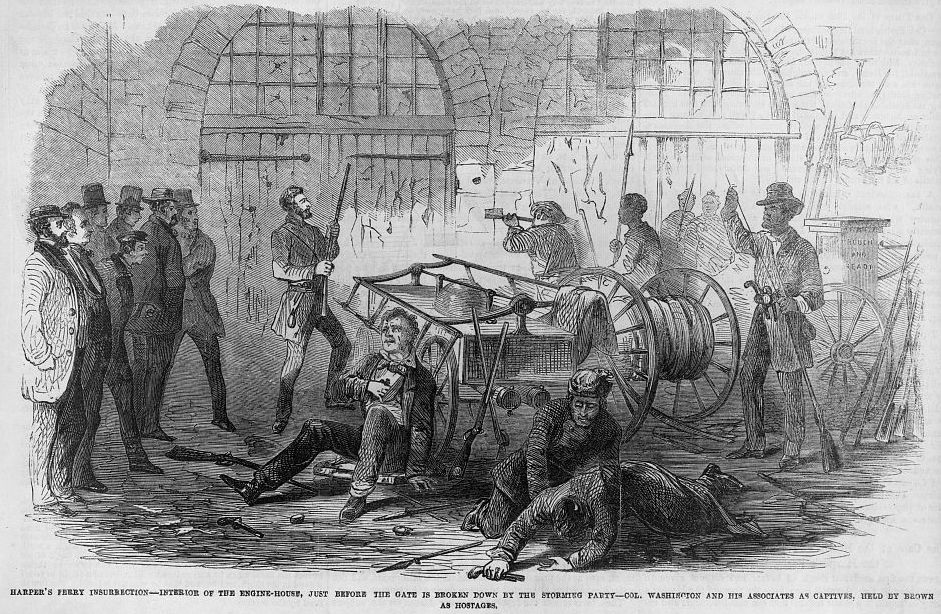

At 6:30 on the morning of Tuesday, October 18, Lee had Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials o ...

(Lee's aide-de-camp) approach the engine house in an attempt to get Brown to surrender. When that failed, he waived his cap which was the signal for Greene and a detail of 12 Marines to storm the engine house. Two Marines armed with sledgehammers tried in vain to break through the door but were soon forced to retreat. Greene found a ladder in the yard that belonged to the engine house and ordered the other ten Marines to use it as a battering ram to knock the front doors in. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington (a great-grandnephew of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

who was being held as a hostage) identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what happened next:

The action inside the engine house happened very quickly. In three minutes, the Marines had killed four of John Brown's men as well as freed all of the hostages, who were starving and distraught, but otherwise unhurt. Brown, who was wounded, and his few followers who were still alive were taken prisoner. One Marine was killed in the action and another one was wounded: Private Luke Quinn was killed during the storming of the engine house when he was shot in the abdomen, and Private Matthew Ruppert was shot in the face inside the engine house (possibly by John Brown himself), but fully recovered.

The next day, Greene and a detail of Marines escorted Brown to nearby Charles Town, and turned him over to the civil authorities. Brown was later tried and executed there.

Confederate Marine Corps

After Virginia declared that it had seceded from the Union, Greene resigned his commission in the U.S. Marine Corps on May 17, 1861. He was one of 16 Marine officers to resign. On July 30, declining an appointment as either a lieutenant colonel in the Virginian infantry or as a colonel in the Wisconsin militia, he joined the newly formedConfederate States Marine Corps

The Confederate States Marine Corps (CSMC), also referred to as the Confederate States Marines, was a branch of the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. It was established by an act of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate State ...

where he was given the rank of captain. He would later be promoted to major and was Adjutant and Inspector of the Corps. He served throughout the war at Confederate Marine headquarters in Richmond until his capture and parole at Farmville, Virginia

Farmville is a town in Prince Edward and Cumberland counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 8,216 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Prince Edward County.

Farmville developed near the headwaters of the Appomattox ...

, in April 1865.

Later life and death

After the Civil War, he lived inClarke County, Virginia

Clarke County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,783. Its county seat is Berryville. Clarke County is included in the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statisti ...

, until about 1873. He then moved west and settled in Mitchell, Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

(now South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large portion ...

) and was a pioneer civil engineer and surveyor. On May 25, 1909, Greene died at the age of 84 on his farm near Mitchell.Dale Lee Sumner, ''The Forgotten Marines'': "The Capture of John Brown" (Lulu.com, 2008), pU; "John Brown's Captor Dead", ''New York Times'', May 27, 1909, p1 He is buried in Graceland Cemetery in Mitchell.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greene, Israel 1824 births 1909 deaths John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry United States Marines People from Plattsburgh, New York Northern-born Confederates Confederate States Marine Corps officers Military personnel from New York (state) People of Virginia in the American Civil War Witnesses to John Brown's execution