Iron(III) compounds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Iron () is a

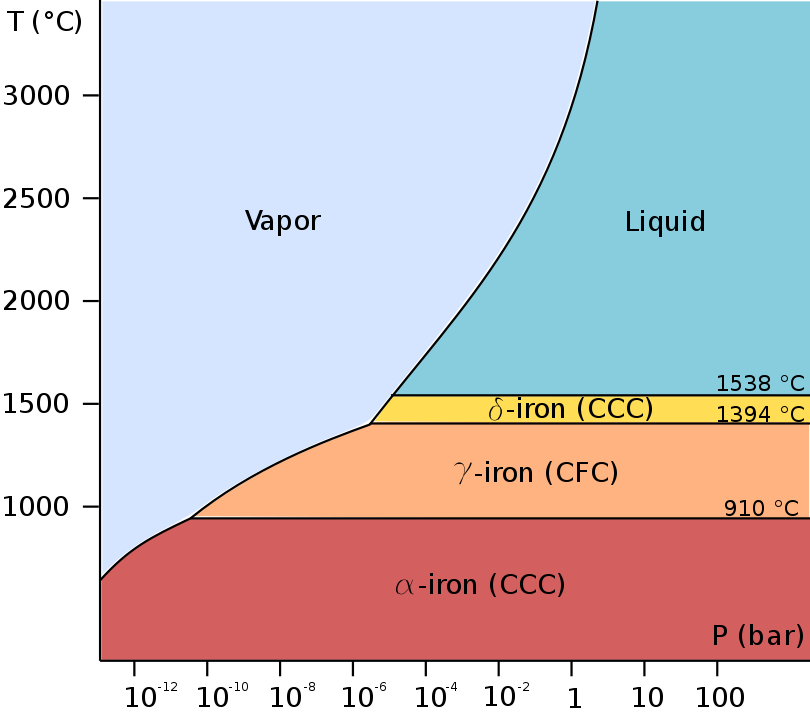

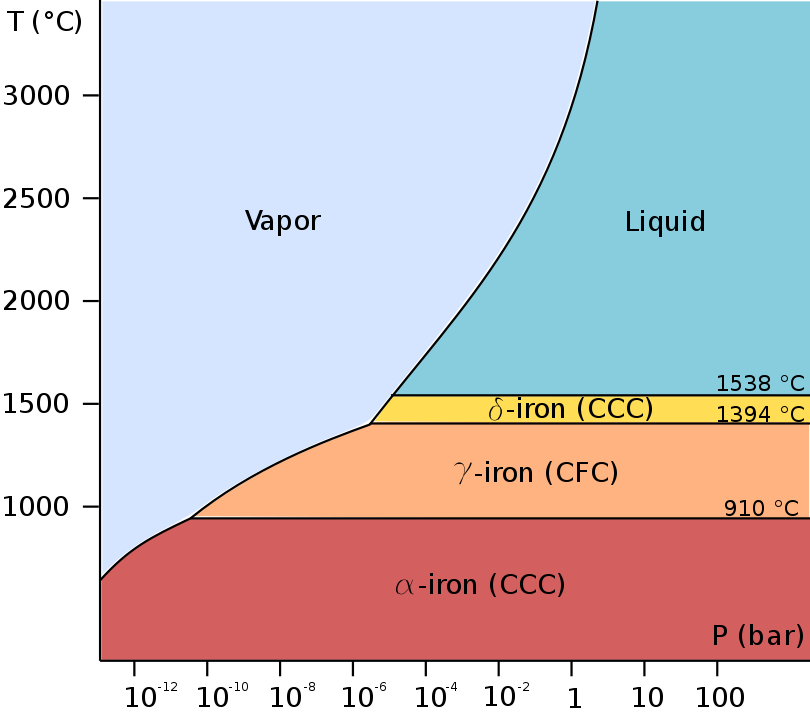

At least four allotropes of iron (differing atom arrangements in the solid) are known, conventionally denoted α, γ, δ, and ε.

At least four allotropes of iron (differing atom arrangements in the solid) are known, conventionally denoted α, γ, δ, and ε.

The first three forms are observed at ordinary pressures. As molten iron cools past its freezing point of 1538 °C, it crystallizes into its δ allotrope, which has a

The first three forms are observed at ordinary pressures. As molten iron cools past its freezing point of 1538 °C, it crystallizes into its δ allotrope, which has a

Below its

Below its

Metallic or

Metallic or

Mindat.org Silicate perovskite may form up to 93% of the lower mantle, and the magnesium iron form, , is considered to be the most abundant mineral in the Earth, making up 38% of its volume.

While iron is the most abundant element on Earth, most of this iron is concentrated in the inner and outer cores. The fraction of iron that is in

While iron is the most abundant element on Earth, most of this iron is concentrated in the inner and outer cores. The fraction of iron that is in  Large deposits of iron are

Large deposits of iron are

The binary ferrous and ferric

The binary ferrous and ferric

The standard reduction potentials in acidic aqueous solution for some common iron ions are given below:Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1075–79

The red-purple tetrahedral

The standard reduction potentials in acidic aqueous solution for some common iron ions are given below:Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1075–79

The red-purple tetrahedral  As pH rises above 0 the above yellow hydrolyzed species form and as it rises above 2–3, reddish-brown hydrous iron(III) oxide precipitates out of solution. Although Fe3+ has a d5 configuration, its absorption spectrum is not like that of Mn2+ with its weak, spin-forbidden d–d bands, because Fe3+ has higher positive charge and is more polarizing, lowering the energy of its ligand-to-metal charge transfer absorptions. Thus, all the above complexes are rather strongly colored, with the single exception of the hexaquo ion – and even that has a spectrum dominated by charge transfer in the near ultraviolet region. On the other hand, the pale green iron(II) hexaquo ion does not undergo appreciable hydrolysis. Carbon dioxide is not evolved when

As pH rises above 0 the above yellow hydrolyzed species form and as it rises above 2–3, reddish-brown hydrous iron(III) oxide precipitates out of solution. Although Fe3+ has a d5 configuration, its absorption spectrum is not like that of Mn2+ with its weak, spin-forbidden d–d bands, because Fe3+ has higher positive charge and is more polarizing, lowering the energy of its ligand-to-metal charge transfer absorptions. Thus, all the above complexes are rather strongly colored, with the single exception of the hexaquo ion – and even that has a spectrum dominated by charge transfer in the near ultraviolet region. On the other hand, the pale green iron(II) hexaquo ion does not undergo appreciable hydrolysis. Carbon dioxide is not evolved when

Many coordination compounds of iron are known. A typical six-coordinate anion is hexachloroferrate(III), eCl6sup>3−, found in the mixed salt

Many coordination compounds of iron are known. A typical six-coordinate anion is hexachloroferrate(III), eCl6sup>3−, found in the mixed salt

Iron(III) complexes are quite similar to those of

Iron(III) complexes are quite similar to those of

Prussian blue or "ferric ferrocyanide", Fe4 e(CN)6sub>3, is an old and well-known iron-cyanide complex, extensively used as pigment and in several other applications. Its formation can be used as a simple wet chemistry test to distinguish between aqueous solutions of Fe2+ and Fe3+ as they react (respectively) with potassium ferricyanide and potassium ferrocyanide to form Prussian blue.

Another old example of an organoiron compound is

Prussian blue or "ferric ferrocyanide", Fe4 e(CN)6sub>3, is an old and well-known iron-cyanide complex, extensively used as pigment and in several other applications. Its formation can be used as a simple wet chemistry test to distinguish between aqueous solutions of Fe2+ and Fe3+ as they react (respectively) with potassium ferricyanide and potassium ferrocyanide to form Prussian blue.

Another old example of an organoiron compound is

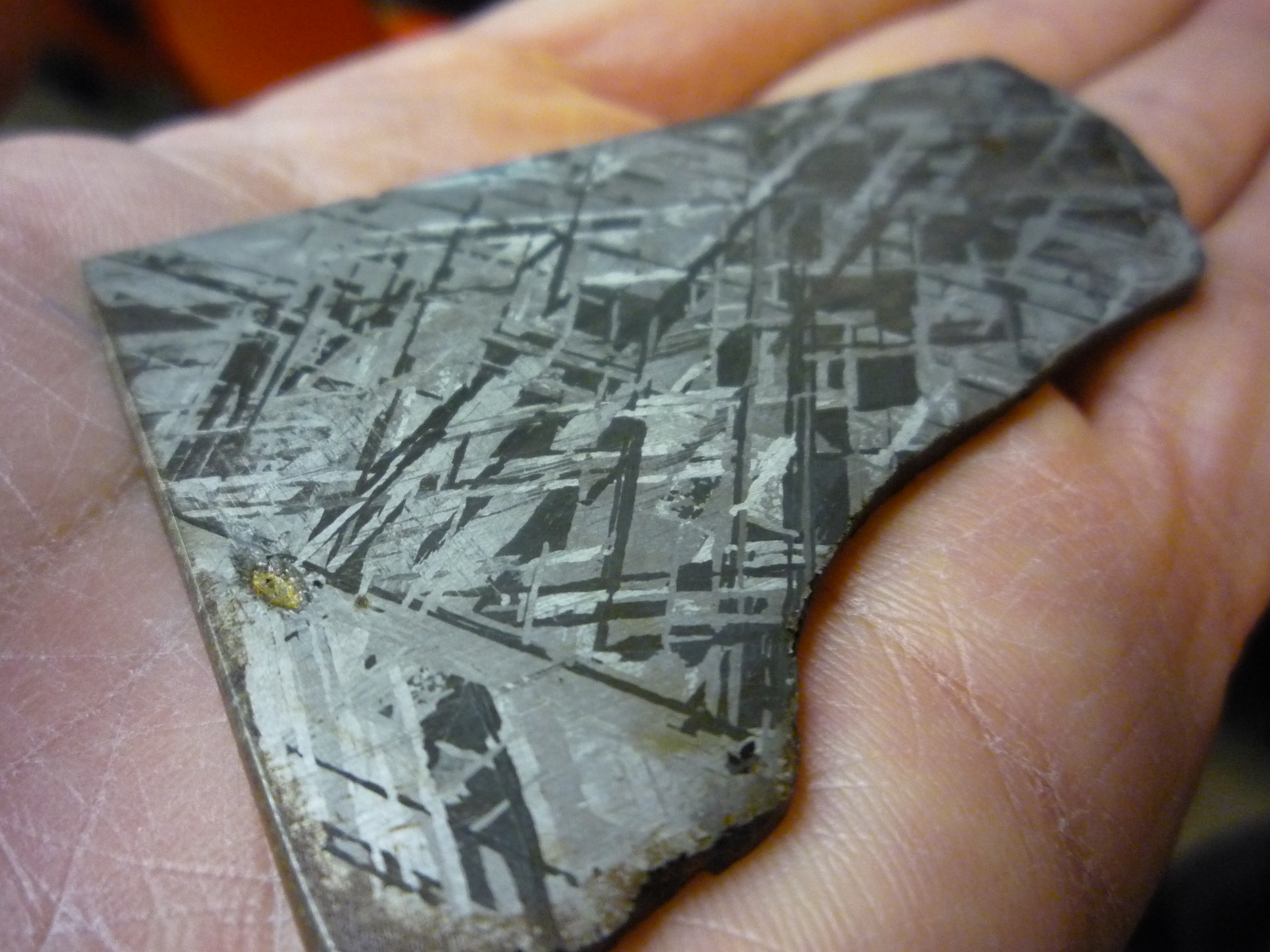

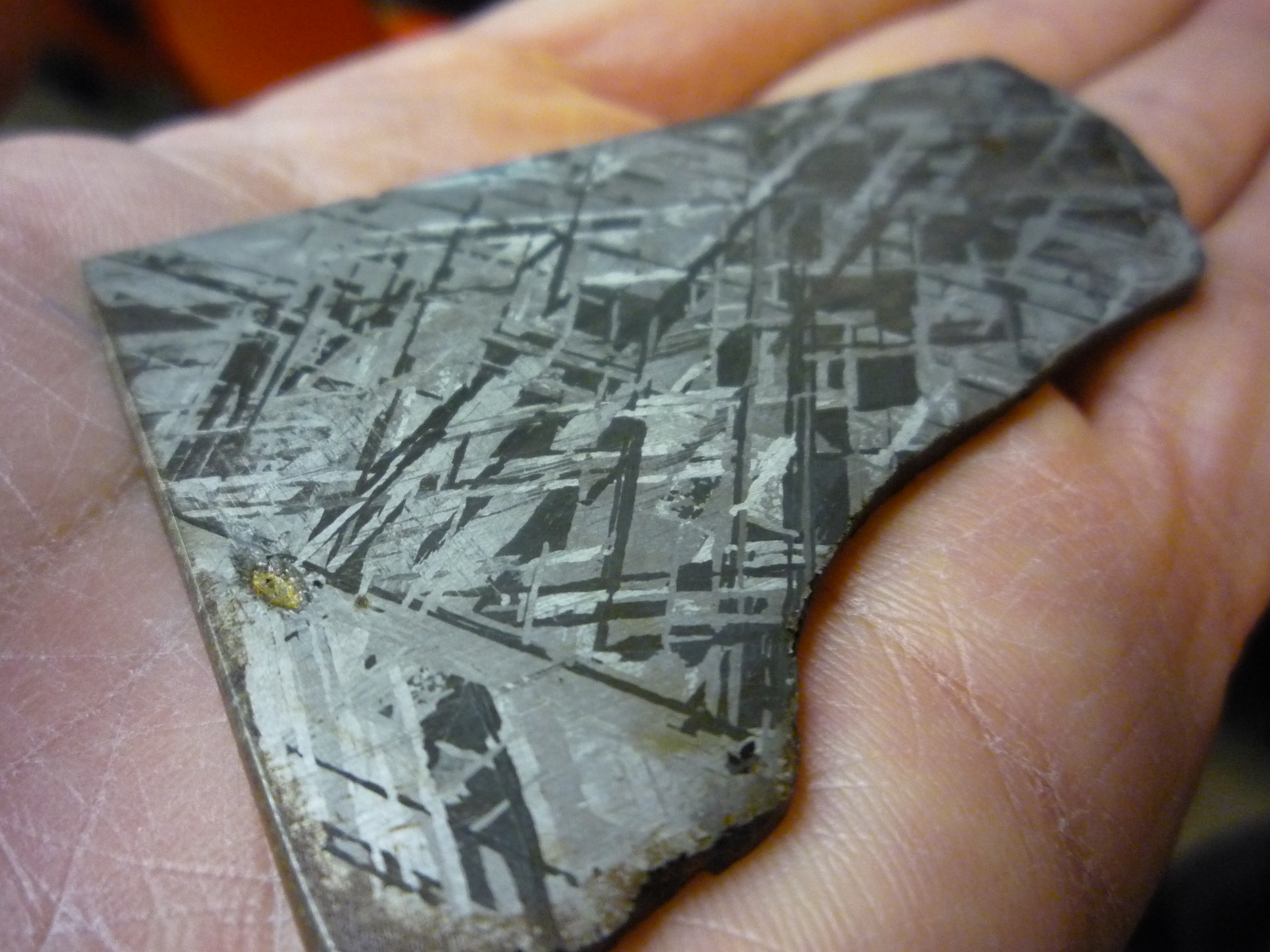

Beads made from meteoric iron in 3500 BC or earlier were found in

Beads made from meteoric iron in 3500 BC or earlier were found in

The first iron production started in the Middle Bronze Age, but it took several centuries before iron displaced bronze. Samples of smelted iron from Asmar, Mesopotamia and Tall Chagar Bazaar in northern Syria were made sometime between 3000 and 2700 BC. The Hittites established an empire in north-central Anatolia around 1600 BC. They appear to be the first to understand the production of iron from its ores and regard it highly in their society. The Hittites began to smelt iron between 1500 and 1200 BC and the practice spread to the rest of the Near East after their empire fell in 1180 BC. The subsequent period is called the Iron Age.

Artifacts of smelted iron are found in India dating from 1800 to 1200 BC, and in the Levant from about 1500 BC (suggesting smelting in Anatolia or the Caucasus). Alleged references (compare

The first iron production started in the Middle Bronze Age, but it took several centuries before iron displaced bronze. Samples of smelted iron from Asmar, Mesopotamia and Tall Chagar Bazaar in northern Syria were made sometime between 3000 and 2700 BC. The Hittites established an empire in north-central Anatolia around 1600 BC. They appear to be the first to understand the production of iron from its ores and regard it highly in their society. The Hittites began to smelt iron between 1500 and 1200 BC and the practice spread to the rest of the Near East after their empire fell in 1180 BC. The subsequent period is called the Iron Age.

Artifacts of smelted iron are found in India dating from 1800 to 1200 BC, and in the Levant from about 1500 BC (suggesting smelting in Anatolia or the Caucasus). Alleged references (compare

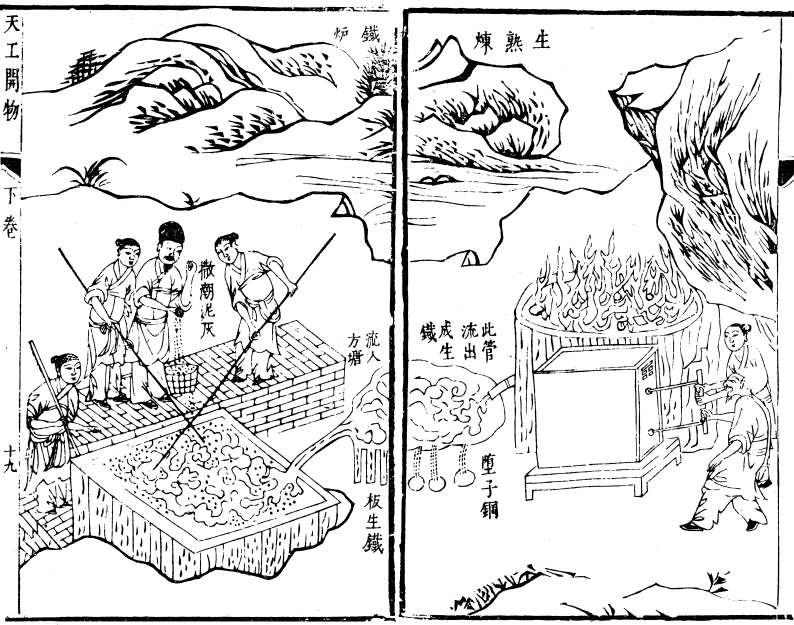

Medieval

Medieval

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every ...

26. It is a metal

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typica ...

that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 Group 8 may refer to:

* Group 8 element, a series of elements in the Periodic Table

* Group 8 Rugby League, a rugby league competition

* Group 8 (Sweden), a feminist movement in Sweden

* Group VIII, former nomenclature for the noble gas

The n ...

of the periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the (chemical) elements, is a rows and columns arrangement of the chemical elements. It is widely used in chemistry, physics, and other sciences, and is generally seen as an icon of ch ...

. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in front of oxygen (32.1% and 30.1%, respectively), forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust.

In its metallic state, iron is rare in the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

, limited mainly to deposition by meteorites. Iron ores, by contrast, are among the most abundant in the Earth's crust, although extracting usable metal from them requires kilns or furnaces capable of reaching or higher, about higher than that required to smelt

Smelt may refer to:

* Smelting, chemical process

* The common name of various fish:

** Smelt (fish), a family of small fish, Osmeridae

** Australian smelt in the family Retropinnidae and species ''Retropinna semoni''

** Big-scale sand smelt ''A ...

copper. Humans started to master that process in Eurasia during the 2nd millennium BCE and the use of iron tools and weapons began to displace copper alloys, in some regions, only around 1200 BCE. That event is considered the transition from the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

to the Iron Age. In the modern world, iron alloys, such as steel, stainless steel, cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

and special steels, are by far the most common industrial metals, because of their mechanical properties and low cost. The iron and steel industry

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in fro ...

is thus very important economically, and iron is the cheapest metal, with a price of a few dollars per kilogram or per pound (see Metal#uses).

Pristine and smooth pure iron surfaces are mirror-like silvery-gray. However, iron reacts readily with oxygen and water to give brown to black hydrated iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which ...

s, commonly known as rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO(OH) ...

. Unlike the oxides of some other metals that form passivating layers, rust occupies more volume than the metal and thus flakes off, exposing more fresh surfaces for corrosion. Although iron readily reacts, high purity iron, called electrolytic iron, has better corrosion resistance.

The body of an adult human contains about 4 grams (0.005% body weight) of iron, mostly in hemoglobin and myoglobin. These two proteins play essential roles in vertebrate metabolism, respectively oxygen transport

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the cir ...

by blood and oxygen storage in muscles. To maintain the necessary levels, human iron metabolism requires a minimum of iron in the diet. Iron is also the metal at the active site of many important redox enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. ...

dealing with cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

and oxidation and reduction in plants and animals.

Chemically, the most common oxidation states of iron are iron(II) and iron(III)

In chemistry, iron(III) refers to the element iron in its +3 oxidation state. In ionic compounds (salts), such an atom may occur as a separate cation (positive ion) denoted by Fe3+.

The adjective ferric or the prefix ferri- is often used to sp ...

. Iron shares many properties of other transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that can ...

s, including the other group 8 element

Group 8 is a group (column) of chemical elements in the periodic table. It consists of iron (Fe), ruthenium (Ru), osmium (Os) and hassium (Hs).Leigh, G. J. ''Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry: Recommendations 1990''. Blackwell Science, 1990. ...

s, ruthenium

Ruthenium is a chemical element with the symbol Ru and atomic number 44. It is a rare transition metal belonging to the platinum group of the periodic table. Like the other metals of the platinum group, ruthenium is inert to most other chemicals ...

and osmium. Iron forms compounds in a wide range of oxidation states, −2 to +7. Iron also forms many coordination compound

A coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the ''coordination centre'', and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ''ligands'' or complexing agents. Many ...

s; some of them, such as ferrocene, ferrioxalate

Ferrioxalate or trisoxalatoferrate(III) is a trivalent anion with formula . It is a transition metal complex consisting of an iron atom in the +3 oxidation state and three bidentate oxalate ions anions acting as ligands.

The ferrioxalate anio ...

, and Prussian blue, have substantial industrial, medical, or research applications.

Characteristics

Allotropes

The first three forms are observed at ordinary pressures. As molten iron cools past its freezing point of 1538 °C, it crystallizes into its δ allotrope, which has a

The first three forms are observed at ordinary pressures. As molten iron cools past its freezing point of 1538 °C, it crystallizes into its δ allotrope, which has a body-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties ...

(bcc) crystal structure. As it cools further to 1394 °C, it changes to its γ-iron allotrope, a face-centered cubic (fcc) crystal structure, or austenite

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a metallic, non-magnetic allotrope of iron or a solid solution of iron with an alloying element. In plain-carbon steel, austenite exists above the critical eutectoid temperature of 1000 K ...

. At 912 °C and below, the crystal structure again becomes the bcc α-iron allotrope.

The physical properties of iron at very high pressures and temperatures have also been studied extensively, because of their relevance to theories about the cores of the Earth and other planets. Above approximately 10 GPa and temperatures of a few hundred kelvin or less, α-iron changes into another hexagonal close-packed

In geometry, close-packing of equal spheres is a dense arrangement of congruent spheres in an infinite, regular arrangement (or lattice). Carl Friedrich Gauss proved that the highest average density – that is, the greatest fraction of space occ ...

(hcp) structure, which is also known as ε-iron. The higher-temperature γ-phase also changes into ε-iron, but does so at higher pressure.

Some controversial experimental evidence exists for a stable β phase at pressures above 50 GPa and temperatures of at least 1500 K. It is supposed to have an orthorhombic or a double hcp structure. (Confusingly, the term "β-iron" is sometimes also used to refer to α-iron above its Curie point, when it changes from being ferromagnetic to paramagnetic, even though its crystal structure has not changed.)

The inner core of the Earth is generally presumed to consist of an iron- nickel alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductility, ...

with ε (or β) structure.

Melting and boiling points

The melting and boiling points of iron, along with itsenthalpy of atomization

In chemistry, the enthalpy of atomization (also atomisation in British English) is the enthalpy change that accompanies the total separation of all atoms in a chemical substance (either an element or a compound). This is often represented by t ...

, are lower than those of the earlier 3d elements from scandium to chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

, showing the lessened contribution of the 3d electrons to metallic bonding as they are attracted more and more into the inert core by the nucleus;Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1116 however, they are higher than the values for the previous element manganese because that element has a half-filled 3d sub-shell and consequently its d-electrons are not easily delocalized. This same trend appears for ruthenium but not osmium.

The melting point of iron is experimentally well defined for pressures less than 50 GPa. For greater pressures, published data (as of 2007) still varies by tens of gigapascals and over a thousand kelvin.

Magnetic properties

Curie point

In physics and materials science, the Curie temperature (''T''C), or Curie point, is the temperature above which certain materials lose their permanent magnetic properties, which can (in most cases) be replaced by induced magnetism. The Cur ...

of , α-iron changes from paramagnetic to ferromagnetic: the spins of the two unpaired electrons in each atom generally align with the spins of its neighbors, creating an overall magnetic field. This happens because the orbitals of those two electrons (d''z''2 and d''x''2 − ''y''2) do not point toward neighboring atoms in the lattice, and therefore are not involved in metallic bonding.

In the absence of an external source of magnetic field, the atoms get spontaneously partitioned into magnetic domains, about 10 micrometers across, such that the atoms in each domain have parallel spins, but some domains have other orientations. Thus a macroscopic piece of iron will have a nearly zero overall magnetic field.

Application of an external magnetic field causes the domains that are magnetized in the same general direction to grow at the expense of adjacent ones that point in other directions, reinforcing the external field. This effect is exploited in devices that need to channel magnetic fields to fulfill design function, such as electrical transformer

A transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces a varying magnetic flux in the transformer's c ...

s, magnetic recording

Magnetic storage or magnetic recording is the storage of data on a magnetized medium. Magnetic storage uses different patterns of magnetisation in a magnetizable material to store data and is a form of non-volatile memory. The information is ac ...

heads, and electric motors. Impurities, lattice defect

A crystallographic defect is an interruption of the regular patterns of arrangement of atoms or molecules in crystalline solids. The positions and orientations of particles, which are repeating at fixed distances determined by the unit cell par ...

s, or grain and particle boundaries can "pin" the domains in the new positions, so that the effect persists even after the external field is removed – thus turning the iron object into a (permanent) magnet.

Similar behavior is exhibited by some iron compounds, such as the ferrites including the mineral magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the ...

, a crystalline form of the mixed iron(II,III) oxide (although the atomic-scale mechanism, ferrimagnetism, is somewhat different). Pieces of magnetite with natural permanent magnetization ( lodestones) provided the earliest compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

es for navigation. Particles of magnetite were extensively used in magnetic recording media such as core memories, magnetic tapes, floppies

A floppy disk or floppy diskette (casually referred to as a floppy, or a diskette) is an obsolescent type of disk storage composed of a thin and flexible disk of a magnetic storage medium in a square or nearly square plastic enclosure lined wi ...

, and disks, until they were replaced by cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pro ...

-based materials.

Isotopes

Iron has four stable isotopes: 54Fe (5.845% of natural iron), 56Fe (91.754%), 57Fe (2.119%) and 58Fe (0.282%). 20-30 artificial isotopes have also been created. Of these stable isotopes, only 57Fe has a nuclear spin (−). Thenuclide

A nuclide (or nucleide, from nucleus, also known as nuclear species) is a class of atoms characterized by their number of protons, ''Z'', their number of neutrons, ''N'', and their nuclear energy state.

The word ''nuclide'' was coined by Truman ...

54Fe theoretically can undergo double electron capture to 54Cr, but the process has never been observed and only a lower limit on the half-life of 3.1×1022 years has been established.

60Fe is an extinct radionuclide of long half-life

Half-life (symbol ) is the time required for a quantity (of substance) to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo radioactive decay or how long stable ato ...

(2.6 million years). It is not found on Earth, but its ultimate decay product is its granddaughter, the stable nuclide 60Ni. Much of the past work on isotopic composition of iron has focused on the nucleosynthesis of 60Fe through studies of meteorites and ore formation. In the last decade, advances in mass spectrometry have allowed the detection and quantification of minute, naturally occurring variations in the ratios of the stable isotope

The term stable isotope has a meaning similar to stable nuclide, but is preferably used when speaking of nuclides of a specific element. Hence, the plural form stable isotopes usually refers to isotopes of the same element. The relative abundanc ...

s of iron. Much of this work is driven by the Earth and planetary science communities, although applications to biological and industrial systems are emerging.

In phases of the meteorites ''Semarkona'' and ''Chervony Kut,'' a correlation between the concentration of 60Ni, the granddaughter of 60Fe, and the abundance of the stable iron isotopes provided evidence for the existence of 60Fe at the time of formation of the Solar System

The formation of the Solar System began about 4.6 billion years ago with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the Sun, while the rest flattened into a ...

. Possibly the energy released by the decay of 60Fe, along with that released by 26Al, contributed to the remelting and differentiation of asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere.

...

s after their formation 4.6 billion years ago. The abundance of 60Ni present in extraterrestrial material may bring further insight into the origin and early history of the Solar System.

The most abundant iron isotope 56Fe is of particular interest to nuclear scientists because it represents the most common endpoint of nucleosynthesis. Since 56Ni (14 alpha particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay, but may also be produce ...

s) is easily produced from lighter nuclei in the alpha process

The alpha process, also known as the alpha ladder, is one of two classes of nuclear fusion reactions by which stars convert helium into heavier elements, the other being the triple-alpha process.

The triple-alpha process consumes only helium, an ...

in nuclear reaction

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, a nuclear reaction is a process in which two nuclei, or a nucleus and an external subatomic particle, collide to produce one or more new nuclides. Thus, a nuclear reaction must cause a transformation o ...

s in supernovae (see silicon burning process), it is the endpoint of fusion chains inside extremely massive stars, since addition of another alpha particle, resulting in 60Zn, requires a great deal more energy. This 56Ni, which has a half-life of about 6 days, is created in quantity in these stars, but soon decays by two successive positron emissions within supernova decay products in the supernova remnant gas cloud, first to radioactive 56Co, and then to stable 56Fe. As such, iron is the most abundant element in the core of red giant

A red giant is a luminous giant star of low or intermediate mass (roughly 0.3–8 solar masses ()) in a late phase of stellar evolution. The outer atmosphere is inflated and tenuous, making the radius large and the surface temperature around or ...

s, and is the most abundant metal in iron meteorites and in the dense metal cores of planets such as Earth.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 12 It is also very common in the universe, relative to other stable metals

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typicall ...

of approximately the same atomic weight

Relative atomic mass (symbol: ''A''; sometimes abbreviated RAM or r.a.m.), also known by the deprecated synonym atomic weight, is a dimensionless physical quantity defined as the ratio of the average mass of atoms of a chemical element in a giv ...

. Iron is the sixth most abundant element in the universe, and the most common refractory element.

Although a further tiny energy gain could be extracted by synthesizing 62Ni, which has a marginally higher binding energy than 56Fe, conditions in stars are unsuitable for this process. Element production in supernovas and distribution on Earth greatly favor iron over nickel, and in any case, 56Fe still has a lower mass per nucleon than 62Ni due to its higher fraction of lighter protons. Hence, elements heavier than iron require a supernova for their formation, involving rapid neutron capture by starting 56Fe nuclei.

In the far future of the universe, assuming that proton decay does not occur, cold fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

occurring via quantum tunnelling would cause the light nuclei in ordinary matter to fuse into 56Fe nuclei. Fission and alpha-particle emission would then make heavy nuclei decay into iron, converting all stellar-mass objects to cold spheres of pure iron.

Origin and occurrence in nature

Cosmogenesis

Iron's abundance in rocky planets like Earth is due to its abundant production during the runaway fusion and explosion of type Ia supernovae, which scatters the iron into space.Metallic iron

Metallic or

Metallic or native iron

Telluric iron, also called native iron, is iron that originated on Earth, and is found in a metallic form rather than as an ore. Telluric iron is extremely rare, with only one known major deposit in the world, located in Greenland.

Introduction

Wi ...

is rarely found on the surface of the Earth because it tends to oxidize. However, both the Earth's inner and outer core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and e ...

, that account for 35% of the mass of the whole Earth, are believed to consist largely of an iron alloy, possibly with nickel. Electric currents in the liquid outer core are believed to be the origin of the Earth's magnetic field. The other terrestrial planets ( Mercury, Venus, and Mars) as well as the Moon are believed to have a metallic core consisting mostly of iron. The M-type asteroids are also believed to be partly or mostly made of metallic iron alloy.

The rare iron meteorites are the main form of natural metallic iron on the Earth's surface. Items made of cold-worked meteoritic iron have been found in various archaeological sites dating from a time when iron smelting had not yet been developed; and the Inuit in Greenland have been reported to use iron from the Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite, also known as the Innaanganeq meteorite, is one of the largest known iron meteorites, classified as a medium octahedrite in chemical group IIIAB. In addition to many small fragments, at least eight large fragments with a ...

for tools and hunting weapons. About 1 in 20 meteorites consist of the unique iron-nickel minerals taenite

Taenite is a mineral found naturally on Earth mostly in iron meteorites. It is an alloy of iron and nickel, with a chemical formula of and nickel proportions of 20% up to 65%.

The name is derived from the Greek ταινία for "band, ribbon" ...

(35–80% iron) and kamacite (90–95% iron). Native iron is also rarely found in basalts that have formed from magmas that have come into contact with carbon-rich sedimentary rocks, which have reduced the oxygen fugacity sufficiently for iron to crystallize. This is known as Telluric iron

Telluric iron, also called native iron, is iron that originated on Earth, and is found in a metallic form rather than as an ore. Telluric iron is extremely rare, with only one known major deposit in the world, located in Greenland.

Introduction

Wi ...

and is described from a few localities, such as Disko Island

Disko Island ( kl, Qeqertarsuaq, da, Diskoøen) is a large island in Baffin Bay, off the west coast of Greenland. It has an area of ,

in West Greenland, Yakutia

Sakha, officially the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia),, is the largest republic of Russia, located in the Russian Far East, along the Arctic Ocean, with a population of roughly 1 million. Sakha comprises half of the area of its governing Far E ...

in Russia and Bühl in Germany.

Mantle minerals

Ferropericlase

Ferropericlase or magnesiowüstite is a magnesium/iron oxide with the chemical formula that is interpreted to be one of the main constituents of the Earth's lower mantle together with the silicate perovskite (), a magnesium/iron silicate with a ...

, a solid solution of periclase (MgO) and wüstite

Wüstite ( Fe O) is a mineral form of iron(II) oxide found with meteorites and native iron. It has a grey colour with a greenish tint in reflected light. Wüstite crystallizes in the isometric-hexoctahedral crystal system in opaque to transluc ...

(FeO), makes up about 20% of the volume of the lower mantle

The lower mantle, historically also known as the mesosphere, represents approximately 56% of Earth's total volume, and is the region from 660 to 2900 km below Earth's surface; between the transition zone and the outer core. The preliminary ...

of the Earth, which makes it the second most abundant mineral phase in that region after silicate perovskite ; it also is the major host for iron in the lower mantle. At the bottom of the transition zone of the mantle, the reaction γ- transforms γ-olivine into a mixture of silicate perovskite and ferropericlase and vice versa. In the literature, this mineral phase of the lower mantle is also often called magnesiowüstite.FerropericlaseMindat.org Silicate perovskite may form up to 93% of the lower mantle, and the magnesium iron form, , is considered to be the most abundant mineral in the Earth, making up 38% of its volume.

Earth's crust

Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

only amounts to about 5% of the overall mass of the crust and is thus only the fourth most abundant element in that layer (after oxygen, silicon, and aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It has ...

).

Most of the iron in the crust is combined with various other elements to form many iron minerals. An important class is the iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which ...

minerals such as hematite (Fe2O3), magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the ...

(Fe3O4), and siderite (FeCO3), which are the major ores of iron. Many igneous rocks also contain the sulfide minerals pyrrhotite

Pyrrhotite is an iron sulfide mineral with the formula Fe(1-x)S (x = 0 to 0.2). It is a nonstoichiometric variant of FeS, the mineral known as troilite.

Pyrrhotite is also called magnetic pyrite, because the color is similar to pyrite and it is ...

and pentlandite

Pentlandite is an iron–nickel sulfide with the chemical formula . Pentlandite has a narrow variation range in Ni:Fe but it is usually described as having a Ni:Fe of 1:1. It also contains minor cobalt, usually at low levels as a fraction of wei ...

.Klein, Cornelis and Cornelius S. Hurlbut, Jr. (1985) ''Manual of Mineralogy,'' Wiley, 20th ed, pp. 278–79 During weathering, iron tends to leach from sulfide deposits as the sulfate and from silicate deposits as the bicarbonate. Both of these are oxidized in aqueous solution and precipitate in even mildly elevated pH as iron(III) oxide.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1071

Large deposits of iron are

Large deposits of iron are banded iron formations

Banded iron formations (also known as banded ironstone formations or BIFs) are distinctive units of sedimentary rock consisting of alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. They can be up to several hundred meters in thickness a ...

, a type of rock consisting of repeated thin layers of iron oxides alternating with bands of iron-poor shale and chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a c ...

. The banded iron formations were laid down in the time between and .

Materials containing finely ground iron(III) oxides or oxide-hydroxides, such as ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

, have been used as yellow, red, and brown pigments since pre-historical times. They contribute as well to the color of various rocks and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay parti ...

s, including entire geological formations like the Painted Hills

The Painted Hills is a geologic site in Wheeler County, Oregon that is one of the three units of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument along with Sheep Rock and Clarno. It totals and is located northwest of Mitchell, Oregon. The Painted H ...

in Oregon and the Buntsandstein

The Buntsandstein (German for ''coloured'' or ''colourful sandstone'') or Bunter sandstone is a lithostratigraphic and allostratigraphic unit (a sequence of rock strata) in the subsurface of large parts of west and central Europe. The Buntsandst ...

("colored sandstone", British Bunter). Through ''Eisensandstein'' (a jurassic 'iron sandstone', e.g. from Donzdorf

Donzdorf is a town in the district of Göppingen in Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany.

It is located 12 km east of Göppingen, and 13 km south of Schwäbisch Gmünd. The town is home to Nuclear Blast Records, one of the biggest h ...

in Germany) and Bath stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City ...

in the UK, iron compounds are responsible for the yellowish color of many historical buildings and sculptures. The proverbial red color of the surface of Mars is derived from an iron oxide-rich regolith.

Significant amounts of iron occur in the iron sulfide mineral pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

(FeS2), but it is difficult to extract iron from it and it is therefore not exploited. In fact, iron is so common that production generally focuses only on ores with very high quantities of it.

According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report

The report Metal Stocks in Society: Scientific Synthesis was the first of six scientific assessments on global metals to be published by the International Resource Panel (IRP) of the United Nations Environment Programme. The IRP provides independe ...

, the global stock of iron in use in society is 2,200 kg per capita. More-developed countries differ in this respect from less-developed countries (7,000–14,000 vs 2,000 kg per capita).

Oceans

Ocean science demonstrated the role of the iron in the ancient seas in both marine biota and climate.Chemistry and compounds

Iron shows the characteristic chemical properties of thetransition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that can ...

s, namely the ability to form variable oxidation states differing by steps of one and a very large coordination and organometallic chemistry: indeed, it was the discovery of an iron compound, ferrocene, that revolutionalized the latter field in the 1950s.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 905 Iron is sometimes considered as a prototype for the entire block of transition metals, due to its abundance and the immense role it has played in the technological progress of humanity. Its 26 electrons are arranged in the configuration

Configuration or configurations may refer to:

Computing

* Computer configuration or system configuration

* Configuration file, a software file used to configure the initial settings for a computer program

* Configurator, also known as choice board ...

rd64s2, of which the 3d and 4s electrons are relatively close in energy, and thus it can lose a variable number of electrons and there is no clear point where further ionization becomes unprofitable.

Iron forms compounds mainly in the oxidation states +2 ( iron(II), "ferrous") and +3 (iron(III)

In chemistry, iron(III) refers to the element iron in its +3 oxidation state. In ionic compounds (salts), such an atom may occur as a separate cation (positive ion) denoted by Fe3+.

The adjective ferric or the prefix ferri- is often used to sp ...

, "ferric"). Iron also occurs in higher oxidation states, e.g. the purple potassium ferrate

Potassium ferrate is the chemical compound with the formula . This purple salt is paramagnetic, and is a rare example of an iron(VI) compound. In most of its compounds, iron has the oxidation state +2 or +3 ( or ). Reflecting its high oxidation st ...

(K2FeO4), which contains iron in its +6 oxidation state. Although iron(VIII) oxide (FeO4) has been claimed, the report could not be reproduced and such a species from the removal of all electrons of the element beyond the preceding inert gas configuration (at least with iron in its +8 oxidation state) has been found to be improbable computationally. However, one form of anionic eO4sup>– with iron in its +7 oxidation state, along with an iron(V)-peroxo isomer, has been detected by infrared spectroscopy at 4 K after cocondensation of laser-ablated Fe atoms with a mixture of O2/Ar. Iron(IV) is a common intermediate in many biochemical oxidation reactions. Numerous organoiron compounds contain formal oxidation states of +1, 0, −1, or even −2. The oxidation states and other bonding properties are often assessed using the technique of Mössbauer spectroscopy. Many mixed valence compound

Mixed valence complexes contain an element which is present in more than one oxidation state. Well-known mixed valence compounds include the Creutz–Taube complex, Prussian blue, and molybdenum blue. Many solids are mixed-valency including in ...

s contain both iron(II) and iron(III) centers, such as magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the ...

and Prussian blue (). The latter is used as the traditional "blue" in blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets. Introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842, the process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited numbe ...

s.

Iron is the first of the transition metals that cannot reach its group oxidation state of +8, although its heavier congeners ruthenium and osmium can, with ruthenium having more difficulty than osmium. Ruthenium exhibits an aqueous cationic chemistry in its low oxidation states similar to that of iron, but osmium does not, favoring high oxidation states in which it forms anionic complexes. In the second half of the 3d transition series, vertical similarities down the groups compete with the horizontal similarities of iron with its neighbors cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pro ...

and nickel in the periodic table, which are also ferromagnetic at room temperature and share similar chemistry. As such, iron, cobalt, and nickel are sometimes grouped together as the iron triad

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in fro ...

.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1070

Unlike many other metals, iron does not form amalgams with mercury. As a result, mercury is traded in standardized 76 pound flasks (34 kg) made of iron.

Iron is by far the most reactive element in its group; it is pyrophoric

A substance is pyrophoric (from grc-gre, πυροφόρος, , 'fire-bearing') if it ignites spontaneously in air at or below (for gases) or within 5 minutes after coming into contact with air (for liquids and solids). Examples are organolith ...

when finely divided and dissolves easily in dilute acids, giving Fe2+. However, it does not react with concentrated nitric acid and other oxidizing acids due to the formation of an impervious oxide layer, which can nevertheless react with hydrochloric acid. High purity iron, called electrolytic iron, is considered to be resistant to rust, due to its oxide layer.

Binary compounds

Oxides and hydroxides

Iron forms various oxide and hydroxide compounds; the most common are iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4), and iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3). Iron(II) oxide also exists, though it is unstable at room temperature. Despite their names, they are actually all non-stoichiometric compounds whose compositions may vary. These oxides are the principal ores for the production of iron (seebloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom''. ...

and blast furnace). They are also used in the production of ferrites, useful magnetic storage media in computers, and pigments. The best known sulfide is iron pyrite (FeS2), also known as fool's gold owing to its golden luster. It is not an iron(IV) compound, but is actually an iron(II) polysulfide containing Fe2+ and ions in a distorted sodium chloride structure.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1079

Halides

The binary ferrous and ferric

The binary ferrous and ferric halide

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a fluor ...

s are well-known. The ferrous halides typically arise from treating iron metal with the corresponding hydrohalic acid

In chemistry, hydrogen halides (hydrohalic acids when in the aqueous phase) are diatomic, inorganic compounds that function as Arrhenius acids. The formula is HX where X is one of the halogens: fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, or astatine. A ...

to give the corresponding hydrated salts.

:Fe + 2 HX → FeX2 + H2 (X = F, Cl, Br, I)

Iron reacts with fluorine, chlorine, and bromine to give the corresponding ferric halides, ferric chloride being the most common.

:2 Fe + 3 X2 → 2 FeX3 (X = F, Cl, Br)

Ferric iodide is an exception, being thermodynamically unstable due to the oxidizing power of Fe3+ and the high reducing power of I−:

:2 I− + 2 Fe3+ → I2 + 2 Fe2+ (E0 = +0.23 V)

Ferric iodide, a black solid, is not stable in ordinary conditions, but can be prepared through the reaction of iron pentacarbonyl

Iron pentacarbonyl, also known as iron carbonyl, is the compound with formula . Under standard conditions Fe( CO)5 is a free-flowing, straw-colored liquid with a pungent odour. Older samples appear darker. This compound is a common precursor to ...

with iodine and carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

in the presence of hexane

Hexane () is an organic compound, a straight-chain alkane with six carbon atoms and has the molecular formula C6H14.

It is a colorless liquid, odorless when pure, and with boiling points approximately . It is widely used as a cheap, relatively ...

and light at the temperature of −20 °C, with oxygen and water excluded. Complexes of ferric iodide with some soft bases are known to be stable compounds.

Solution chemistry

The standard reduction potentials in acidic aqueous solution for some common iron ions are given below:Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1075–79

The red-purple tetrahedral

The standard reduction potentials in acidic aqueous solution for some common iron ions are given below:Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1075–79

The red-purple tetrahedral ferrate Ferrate loosely refers to a material that can be viewed as containing anionic iron complexes. Examples include tetrachloroferrate ( eCl4sup>2−), oxyanions ( ), tetracarbonylferrate ( e(CO)4sup>2−), the organoferrates. The term ferrate derives f ...

(VI) anion is such a strong oxidizing agent that it oxidizes nitrogen and ammonia at room temperature, and even water itself in acidic or neutral solutions:Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1082–84

:4 + 10 → 4 + 20 + 3 O2

The Fe3+ ion has a large simple cationic chemistry, although the pale-violet hexaquo ion is very readily hydrolyzed when pH increases above 0 as follows:Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1088–91

As pH rises above 0 the above yellow hydrolyzed species form and as it rises above 2–3, reddish-brown hydrous iron(III) oxide precipitates out of solution. Although Fe3+ has a d5 configuration, its absorption spectrum is not like that of Mn2+ with its weak, spin-forbidden d–d bands, because Fe3+ has higher positive charge and is more polarizing, lowering the energy of its ligand-to-metal charge transfer absorptions. Thus, all the above complexes are rather strongly colored, with the single exception of the hexaquo ion – and even that has a spectrum dominated by charge transfer in the near ultraviolet region. On the other hand, the pale green iron(II) hexaquo ion does not undergo appreciable hydrolysis. Carbon dioxide is not evolved when

As pH rises above 0 the above yellow hydrolyzed species form and as it rises above 2–3, reddish-brown hydrous iron(III) oxide precipitates out of solution. Although Fe3+ has a d5 configuration, its absorption spectrum is not like that of Mn2+ with its weak, spin-forbidden d–d bands, because Fe3+ has higher positive charge and is more polarizing, lowering the energy of its ligand-to-metal charge transfer absorptions. Thus, all the above complexes are rather strongly colored, with the single exception of the hexaquo ion – and even that has a spectrum dominated by charge transfer in the near ultraviolet region. On the other hand, the pale green iron(II) hexaquo ion does not undergo appreciable hydrolysis. Carbon dioxide is not evolved when carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate g ...

anions are added, which instead results in white iron(II) carbonate being precipitated out. In excess carbon dioxide this forms the slightly soluble bicarbonate, which occurs commonly in groundwater, but it oxidises quickly in air to form iron(III) oxide that accounts for the brown deposits present in a sizeable number of streams.Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1091–97

Coordination compounds

Due to its electronic structure, iron has a very large coordination and organometallic chemistry.tetrakis(methylammonium) hexachloroferrate(III) chloride

Tetrakis(methylammonium) hexachloroferrate(III) chloride is a chemical compound with the formula (CH3NH3)4 eCl6l.

Properties

The compound has the form of hygroscopic orange crystals. The hexachloroferrate(III) anion is a coordination complex ce ...

. Complexes with multiple bidentate ligands have geometric isomers. For example, the ''trans''-chlorohydridobis(bis-1,2-(diphenylphosphino)ethane)iron(II)

Chlorobis(dppe)iron hydride is a coordination complex with the formula HFeCl(dppe)2, where dppe is the bidentate ligand 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane. It is a red-violet solid. The compound has attracted much attention as a precursor to dihyd ...

complex is used as a starting material for compounds with the moiety

Moiety may refer to:

Chemistry

* Moiety (chemistry), a part or functional group of a molecule

** Moiety conservation, conservation of a subgroup in a chemical species

Anthropology

* Moiety (kinship), either of two groups into which a society is ...

. The ferrioxalate ion with three oxalate ligands (shown at right) displays helical chirality

Helical may refer to:

* Helix

A helix () is a shape like a corkscrew or spiral staircase. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is for ...

with its two non-superposable geometries labelled ''Λ'' (lambda) for the left-handed screw axis and ''Δ'' (delta) for the right-handed screw axis, in line with IUPAC conventions. Potassium ferrioxalate is used in chemical actinometry

Actinometers are instruments used to measure the heating power of radiation. They are used in meteorology to measure solar radiation as pyranometers, pyrheliometers and net radiometers.

An actinometer is a chemical system or physical device which ...

and along with its sodium salt

Sodium salts are salts composed of a sodium cation and the conjugate base anion of some inorganic or organic acids. They can be formed by the neutralization of such acids with sodium hydroxide.

Categorization

Sodium salts can be categorized in ...

undergoes photoreduction applied in old-style photographic processes. The dihydrate

In chemistry, a hydrate is a substance that contains water or its constituent elements. The chemical state of the water varies widely between different classes of hydrates, some of which were so labeled before their chemical structure was understo ...

of iron(II) oxalate

Ferrous oxalate, or iron(II) oxalate, is an inorganic compound with the formula FeC2O4 where is typically 2. These are orange compounds, poorly soluble in water.

Structure

The dihydrate FeC2O4 is a coordination polymer, consisting of chains of ...

has a polymeric structure with co-planar oxalate ions bridging between iron centres with the water of crystallisation located forming the caps of each octahedron, as illustrated below.

Iron(III) complexes are quite similar to those of

Iron(III) complexes are quite similar to those of chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

(III) with the exception of iron(III)'s preference for ''O''-donor instead of ''N''-donor ligands. The latter tend to be rather more unstable than iron(II) complexes and often dissociate in water. Many Fe–O complexes show intense colors and are used as tests for phenols or enol

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene (olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The ter ...

s. For example, in the ferric chloride test The ferric chloride test is used to determine the presence of phenols in a given sample or compound (for instance natural phenols in a plant extract). Enols, hydroxamic acids, oximes, and sulfinic acids give positive results as well. The bromine te ...

, used to determine the presence of phenols, iron(III) chloride

Iron(III) chloride is the inorganic compound with the formula . Also called ferric chloride, it is a common compound of iron in the +3 oxidation state. The anhydrous compound is a crystalline solid with a melting point of 307.6 °C. The colo ...

reacts with a phenol to form a deep violet complex:

:3 ArOH + FeCl3 → Fe(OAr)3 + 3 HCl (Ar = aryl

In organic chemistry, an aryl is any functional group or substituent derived from an aromatic ring, usually an aromatic hydrocarbon, such as phenyl and naphthyl. "Aryl" is used for the sake of abbreviation or generalization, and "Ar" is used as ...

)

Among the halide and pseudohalide complexes, fluoro complexes of iron(III) are the most stable, with the colorless eF5(H2O)sup>2− being the most stable in aqueous solution. Chloro complexes are less stable and favor tetrahedral coordination as in eCl4sup>−; eBr4sup>− and eI4sup>− are reduced easily to iron(II). Thiocyanate is a common test for the presence of iron(III) as it forms the blood-red e(SCN)(H2O)5sup>2+. Like manganese(II), most iron(III) complexes are high-spin, the exceptions being those with ligands that are high in the spectrochemical series such as cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a ...

. An example of a low-spin iron(III) complex is e(CN)6sup>3−. The cyanide ligands may easily be detached in e(CN)6sup>3−, and hence this complex is poisonous, unlike the iron(II) complex e(CN)6sup>4− found in Prussian blue, which does not release hydrogen cyanide except when dilute acids are added. Iron shows a great variety of electronic spin states, including every possible spin quantum number value for a d-block element from 0 (diamagnetic) to (5 unpaired electrons). This value is always half the number of unpaired electrons. Complexes with zero to two unpaired electrons are considered low-spin and those with four or five are considered high-spin.

Iron(II) complexes are less stable than iron(III) complexes but the preference for ''O''-donor ligands is less marked, so that for example is known while is not. They have a tendency to be oxidized to iron(III) but this can be moderated by low pH and the specific ligands used.

Organometallic compounds

Organoiron chemistry

Organoiron chemistry is the chemistry of iron compounds containing a carbon-to-iron chemical bond. Organoiron compounds are relevant in organic synthesis as reagents such as iron pentacarbonyl, diiron nonacarbonyl and disodium tetracarbonylferrate ...

is the study of organometallic compound

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

s of iron, where carbon atoms are covalently bound to the metal atom. They are many and varied, including cyanide complexes, carbonyl complex

Metal carbonyls are coordination complexes of transition metals with carbon monoxide ligands. Metal carbonyls are useful in organic synthesis and as catalysts or catalyst precursors in homogeneous catalysis, such as hydroformylation and Reppe ch ...

es, sandwich and half-sandwich compounds.

Prussian blue or "ferric ferrocyanide", Fe4 e(CN)6sub>3, is an old and well-known iron-cyanide complex, extensively used as pigment and in several other applications. Its formation can be used as a simple wet chemistry test to distinguish between aqueous solutions of Fe2+ and Fe3+ as they react (respectively) with potassium ferricyanide and potassium ferrocyanide to form Prussian blue.

Another old example of an organoiron compound is

Prussian blue or "ferric ferrocyanide", Fe4 e(CN)6sub>3, is an old and well-known iron-cyanide complex, extensively used as pigment and in several other applications. Its formation can be used as a simple wet chemistry test to distinguish between aqueous solutions of Fe2+ and Fe3+ as they react (respectively) with potassium ferricyanide and potassium ferrocyanide to form Prussian blue.

Another old example of an organoiron compound is iron pentacarbonyl

Iron pentacarbonyl, also known as iron carbonyl, is the compound with formula . Under standard conditions Fe( CO)5 is a free-flowing, straw-colored liquid with a pungent odour. Older samples appear darker. This compound is a common precursor to ...

, Fe(CO)5, in which a neutral iron atom is bound to the carbon atoms of five carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

molecules. The compound can be used to make carbonyl iron Carbonyl iron is a highly pure (97.5% for grade S, 99.5+% for grade R) iron, prepared by chemical decomposition of purified iron pentacarbonyl. It usually has the appearance of grey powder, composed of spherical microparticles. Most of the impuriti ...

powder, a highly reactive form of metallic iron. Thermolysis

Thermal decomposition, or thermolysis, is a chemical decomposition caused by heat. The decomposition temperature of a substance is the temperature at which the substance chemically decomposes. The reaction is usually endothermic as heat is re ...

of iron pentacarbonyl gives triiron dodecacarbonyl

Triiron dodecarbonyl is the organoiron compound with the formula Fe3(CO)12. It is a dark green solid that sublimes under vacuum. It is soluble in nonpolar organic solvents to give intensely green solutions. Most low-nuclearity clusters are pale ...

, , a complex with a cluster of three iron atoms at its core. Collman's reagent, disodium tetracarbonylferrate

Disodium tetracarbonylferrate is the organoiron compound with the formula Na2 e(CO)4 It is always used as a solvate, e.g., with tetrahydrofuran or dimethoxyethane, which bind to the sodium cation. An oxygen-sensitive colourless solid, it is a reag ...

, is a useful reagent for organic chemistry; it contains iron in the −2 oxidation state. Cyclopentadienyliron dicarbonyl dimer

Cyclopentadienyliron dicarbonyl dimer is an organometallic compound with the formula ''η''5-C5H5)Fe(CO)2sub>2, often abbreviated to Cp2Fe2(CO)4, pFe(CO)2sub>2 or even Fp2, with the colloquial name "fip dimer". It is a dark reddish-purple crysta ...

contains iron in the rare +1 oxidation state.

A landmark in this field was the discovery in 1951 of the remarkably stable sandwich compound

In organometallic chemistry, a sandwich compound is a chemical compound featuring a metal bound by haptic, covalent bonds to two arene (ring) ligands. The arenes have the formula , substituted derivatives (for example ) and heterocyclic derivat ...

ferrocene , by Pauson and Kealy and independently by Miller and colleagues, whose surprising molecular structure was determined only a year later by Woodward and Wilkinson and Fischer.

Ferrocene is still one of the most important tools and models in this class.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1104

Iron-centered organometallic species are used as catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the reaction rate, rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the ...

s. The Knölker complex, for example, is a transfer hydrogenation

In chemistry, transfer hydrogenation is a chemical reaction involving the addition of hydrogen to a compound from a source other than molecular . It is applied in laboratory and industrial organic synthesis to saturate organic compounds and reduc ...

catalyst for ketones.

Industrial uses

The iron compounds produced on the largest scale in industry areiron(II) sulfate

Iron(II) sulfate (British English: iron(II) sulphate) or ferrous sulfate denotes a range of salts with the formula Fe SO4·''x''H2O. These compounds exist most commonly as the heptahydrate (''x'' = 7) but several values for x are know ...

(FeSO4·7 H2O) and iron(III) chloride

Iron(III) chloride is the inorganic compound with the formula . Also called ferric chloride, it is a common compound of iron in the +3 oxidation state. The anhydrous compound is a crystalline solid with a melting point of 307.6 °C. The colo ...

(FeCl3). The former is one of the most readily available sources of iron(II), but is less stable to aerial oxidation than Mohr's salt

Ammonium iron(II) sulfate, or Mohr's salt, is the inorganic compound with the formula (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2(H2O)6. Containing two different cations, Fe2+ and NH4+, it is classified as a double salt of ferrous sulfate and ammonium sulfate. It is a comm ...

(). Iron(II) compounds tend to be oxidized to iron(III) compounds in the air.

History

Development of iron metallurgy

Iron is one of the elements undoubtedly known to the ancient world. It has been worked, or wrought, for millennia. However, iron artefacts of great age are much rarer than objects made of gold or silver due to the ease with which iron corrodes. The technology developed slowly, and even after the discovery of smelting it took many centuries for iron to replace bronze as the metal of choice for tools and weapons.Meteoritic iron

Beads made from meteoric iron in 3500 BC or earlier were found in

Beads made from meteoric iron in 3500 BC or earlier were found in Gerzeh

The Gerzeh culture, also called Naqada II, refers to the archaeological stage at Gerzeh (also Girza or Jirzah), a prehistoric Egyptian cemetery located along the west bank of the Nile. The necropolis is named after el-Girzeh, the nearby cont ...

, Egypt by G.A. Wainwright. The beads contain 7.5% nickel, which is a signature of meteoric origin since iron found in the Earth's crust generally has only minuscule nickel impurities.

Meteoric iron was highly regarded due to its origin in the heavens and was often used to forge weapons and tools. For example, a dagger made of meteoric iron was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, containing similar proportions of iron, cobalt, and nickel to a meteorite discovered in the area, deposited by an ancient meteor shower. Items that were likely made of iron by Egyptians date from 3000 to 2500 BC.

Meteoritic iron is comparably soft and ductile and easily cold forged but may get brittle when heated because of the nickel content.

Wrought iron

history of metallurgy in South Asia

The history of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent began prior to the 3rd millennium BCE and continued well into the British Raj. Metals and related concepts were mentioned in various early Vedic age texts. The Rigveda already uses the Sanskrit ...

) to iron in the Indian Vedas have been used for claims of a very early usage of iron in India respectively to date the texts as such. The rigveda term ''ayas'' (metal) refers to copper, while iron which is called as ''śyāma ayas'', literally "black copper", first is mentioned in the post-rigvedic Atharvaveda

The Atharva Veda (, ' from ' and ''veda'', meaning "knowledge") is the "knowledge storehouse of ''atharvāṇas'', the procedures for everyday life".Laurie Patton (2004), Veda and Upanishad, in ''The Hindu World'' (Editors: Sushil Mittal and G ...

.

Some archaeological evidence suggests iron was smelted in Zimbabwe and southeast Africa as early as the eighth century BC. Iron working was introduced to Greece in the late 11th century BC, from which it spread quickly throughout Europe.

The spread of ironworking in Central and Western Europe is associated with Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

expansion. According to Pliny the Elder, iron use was common in the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

era. In the lands of what is now considered China, iron appears approximately 700–500 BC. Iron smelting may have been introduced into China through Central Asia.Pigott, Vincent C. (1999). ''The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. , p. 8. The earliest evidence of the use of a blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

in China dates to the 1st century AD, and cupola furnaces were used as early as the Warring States period (403–221 BC).Pigott, Vincent C. (1999). ''The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. , p. 191. Usage of the blast and cupola furnace remained widespread during the Tang and Song dynasties.

During the Industrial Revolution in Britain, Henry Cort

Henry Cort (c. 1740 – 23 May 1800) was an English ironware producer although formerly a Navy pay agent. During the Industrial Revolution in England, Cort began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative produc ...

began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative production systems. In 1783 he patented the puddling process for refining iron ore. It was later improved by others, including Joseph Hall.

Cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

was first produced in China during 5th century BC, but was hardly in Europe until the medieval period. The earliest cast iron artifacts were discovered by archaeologists in what is now modern Luhe County, Jiangsu in China. Cast iron was used in ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the ''Book of Documents'' (early chapter ...

for warfare, agriculture, and architecture. During the medieval period, means were found in Europe of producing wrought iron from cast iron (in this context known as pig iron) using finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery ...

s. For all these processes, charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

was required as fuel.

Medieval

Medieval blast furnaces

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

were about tall and made of fireproof brick; forced air was usually provided by hand-operated bellows. Modern blast furnaces have grown much bigger, with hearths fourteen meters in diameter that allow them to produce thousands of tons of iron each day, but essentially operate in much the same way as they did during medieval times.

In 1709, Abraham Darby I

Abraham Darby, in his later life called Abraham Darby the Elder, now sometimes known for convenience as Abraham Darby I (14 April 1677 – 5 May 1717, the first and best known of several men of that name), was an English ironmaster and found ...

established a coke-fired blast furnace to produce cast iron, replacing charcoal, although continuing to use blast furnaces. The ensuing availability of inexpensive iron was one of the factors leading to the Industrial Revolution. Toward the end of the 18th century, cast iron began to replace wrought iron for certain purposes, because it was cheaper. Carbon content in iron was not implicated as the reason for the differences in properties of wrought iron, cast iron, and steel until the 18th century.

Since iron was becoming cheaper and more plentiful, it also became a major structural material following the building of the innovative first iron bridge in 1778. This bridge still stands today as a monument to the role iron played in the Industrial Revolution. Following this, iron was used in rails, boats, ships, aqueducts, and buildings, as well as in iron cylinders in steam engines.Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1072 Railways have been central to the formation of modernity and ideas of progress and various languages (e.g. French, Spanish, Italian and German) refer to railways as ''iron road''.

Steel

Steel (with smaller carbon content than pig iron but more than wrought iron) was first produced in antiquity by using abloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom''. ...

. Blacksmiths in Luristan in western Persia were making good steel by 1000 BC. Then improved versions, Wootz steel by India and Damascus steel

Damascus steel was the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by ...

were developed around 300 BC and AD 500 respectively. These methods were specialized, and so steel did not become a major commodity until the 1850s.

New methods of producing it by carburizing

Carburising, carburizing (chiefly American English), or carburisation is a heat treatment process in which iron or steel absorbs carbon while the metal is heated in the presence of a carbon-bearing material, such as charcoal or carbon monoxide. ...

bars of iron in the cementation process

The cementation process is an obsolete technology for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcote Steel F ...

were devised in the 17th century. In the Industrial Revolution, new methods of producing bar iron without charcoal were devised and these were later applied to produce steel. In the late 1850s, Henry Bessemer invented a new steelmaking process, involving blowing air through molten pig iron, to produce mild steel. This made steel much more economical, thereby leading to wrought iron no longer being produced in large quantities.

Foundations of modern chemistry

In 1774,Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

Iron plays a certain role in mythology and has found various usage

Iron plays a certain role in mythology and has found various usage

The pig iron produced by the blast furnace process contains up to 4–5% carbon (by mass), with small amounts of other impurities like sulfur, magnesium, phosphorus, and manganese. This high level of carbon makes it relatively weak and brittle. Reducing the amount of carbon to 0.002–2.1% produces

The pig iron produced by the blast furnace process contains up to 4–5% carbon (by mass), with small amounts of other impurities like sulfur, magnesium, phosphorus, and manganese. This high level of carbon makes it relatively weak and brittle. Reducing the amount of carbon to 0.002–2.1% produces