Ion Antonescu (; ; – 1 June 1946) was a

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n military officer and

marshal who presided over two successive

wartime dictatorships as

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

and ''

Conducător

''Conducător'' (, "Leader") was the title used officially by Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu during World War II, also occasionally used in official discourse to refer to Carol II and Nicolae Ceaușescu.

History

The word is derived from the Ro ...

'' during most of World War II.

A

Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

career officer who made his name during the

1907 peasants' revolt and the

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

Romanian Campaign

The Kingdom of Romania was neutral for the first two years of World War I, entering on the side of the Allied powers from 27 August 1916 until Central Power occupation led to the Treaty of Bucharest in May 1918, before reentering the war on 1 ...

, the antisemitic Antonescu sympathized with the

far-right and

fascist National Christian and

Iron Guard groups for much of the interwar period. He was a

military attaché to France and later

Chief of the General Staff, briefly serving as

Defense Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in s ...

in the National Christian cabinet of

Octavian Goga as well as the subsequent

First Cristea cabinet, in which he also served as Air and Marine Minister. During the late 1930s, his political stance brought him into conflict with King

Carol II and led to his detainment. Antonescu nevertheless rose to political prominence during the political crisis of 1940, and established the

National Legionary State, an uneasy partnership with the Iron Guard's leader

Horia Sima. After entering Romania into an alliance with

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and ensuring

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

's confidence, he eliminated the Guard during the

Legionary Rebellion

Between 21 and 23 January 1941, a rebellion of the Iron Guard paramilitary organization, whose members were known as Legionnaires, occurred in Bucharest, Romania. As their privileges were being gradually removed by the ''Conducător'' Ion An ...

of 1941. In addition to being Prime Minister, he served as his own Foreign Minister and Defense Minister. Soon after Romania joined the Axis in

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, recovering

Bessarabia and

Northern Bukovina, Antonescu also became

Marshal of Romania.

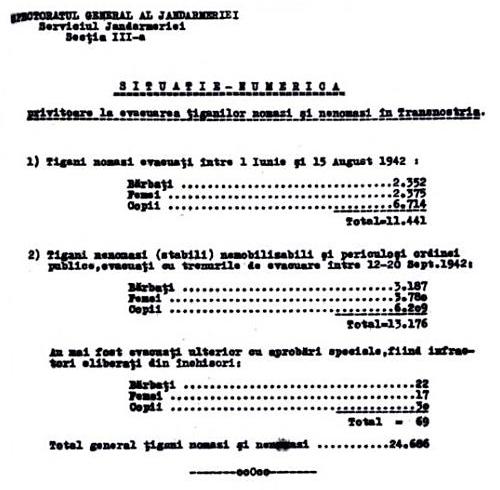

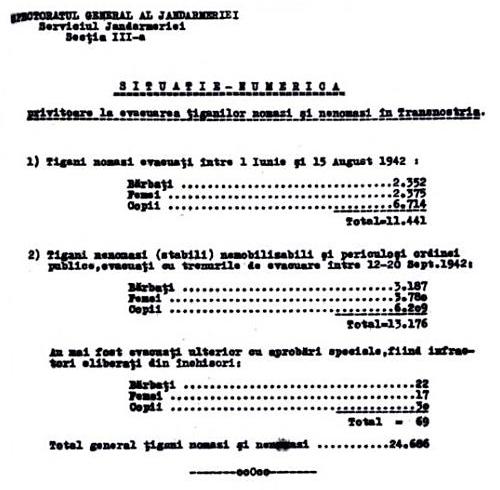

An atypical figure among

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

perpetrators, Antonescu enforced policies independently responsible for the deaths of as many as 400,000 people, most of them

Bessarabian,

Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

and

Romanian Jews, as well as

Romanian Romani. The regime's

complicity in the Holocaust combined pogroms and mass murders such as the

Odessa massacre with

ethnic cleansing, and systematic deportations to occupied

Transnistria. The system in place was nevertheless characterized by singular inconsistencies, prioritizing plunder over killing, showing leniency toward most Jews in the

Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

, and ultimately refusing to adopt the

Final Solution as applied throughout

Nazi-occupied Europe. This was made possible by the fact that Romania, as a junior ally of Nazi Germany, was able to avoid being occupied by the

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

and preserve a degree of political autonomy.

Aerial attacks on Romania by the Allies occurred in 1944 and Romanian troops suffered heavy casualties on the

Eastern Front, prompting Antonescu to open peace negotiations with the Allies, ending with inconclusive results. On 23 August 1944, the king

Michael I led

a coup d'état against Antonescu, who was arrested; after the war he was convicted of war crimes, and executed in June 1946. His involvement in the Holocaust was officially reasserted and condemned following the 2003

Wiesel Commission report.

Biography

Early life and career

Born in the town of

Pitești, north-west of the capital

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

, Antonescu was the

scion of an

upper-middle class Romanian Orthodox family with some military tradition.

[Deletant, p. 37] He was especially close to his mother, Lița Baranga, who survived his death. His father, an army officer, wanted Ion to follow in his footsteps and thus sent him to attend the Infantry and Cavalry School in

Craiova.

[ During his childhood, his father divorced his mother to marry a woman who was a Jewish convert to Orthodoxy.][Ancel, Jean "Antonescu and the Jews" pp. 463–479 from ''The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Reexamined'' edited by Michael Berenbaum and Abraham Peck, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998 p. 465.] The breakup of his parents' marriage was a traumatic event for the young Antonescu, and he made no secret of his dislike of his stepmother, whom he always depicted as a ''femme fatale'' who destroyed what he saw as his parents' happy marriage.Wilhelm Filderman

Wilhelm Filderman (last name also spelled Fieldermann; 14 November 1882 – 1963) was a lawyer and the leader of the Romanian-Jewish community between 1919 and 1947; in addition, he was a representative of the Jews in the Romanian parliament.

Ea ...

, the future Romanian Jewish community activist whose interventions with ''Conducător'' Antonescu helped save a number of his coreligionists. After graduation, in 1904, Antonescu joined the Romanian Army with the rank of Second Lieutenant. He spent the following two years attending courses at the Special Cavalry Section in Târgoviște

Târgoviște (, alternatively spelled ''Tîrgoviște''; german: Tergowisch) is a city and county seat in Dâmbovița County, Romania. It is situated north-west of Bucharest, on the right bank of the Ialomița River.

Târgoviște was one of ...

.[ Reportedly, Antonescu was a zealous and goal-setting student, upset by the slow pace of promotions, and compensated for his diminutive stature through toughness.][Delia Radu]

"Serialul 'Ion Antonescu și asumarea istoriei' (1)"

BBC, Romanian edition, 1 August 2008. In time, the reputation of being a tough and ruthless commander, together with his reddish hair, earned him the nickname ''Câinele Roșu'' ("The Red Dog").[ Antonescu also developed a reputation for questioning his commanders and for appealing over their heads whenever he felt they were wrong.][

During the repression of the 1907 peasants' revolt, he headed a cavalry unit in ]Covurlui County

Covurlui County is one of the historic counties of Moldavia, Romania. The county seat was Galați.

In 1938, the county was disestablished and incorporated into the newly formed Ținutul Dunării, but it was re-established in 1940 after the fall o ...

.[ Opinions on his role in the events diverge: while some historians believe Antonescu was a particularly violent participant in quelling the revolt,][Veiga, p. 301] others equate his participation with that of regular officers[ or view it as outstandingly tactful.][ In addition to restricting peasant protests, Antonescu's unit subdued ]socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

activities in Galați port.[ His handling of the situation earned him praise from ]King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Carol I

Carol I or Charles I of Romania (20 April 1839 – ), born Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, was the monarch of Romania from 1866 to his death in 1914, ruling as Prince (''Domnitor'') from 1866 to 1881, and as King from 1881 to 1914. He w ...

, who sent Crown Prince (future monarch) Ferdinand to congratulate him in front of the whole garrison.[ The following year, Antonescu was promoted to Lieutenant, and, between 1911 and 1913, he attended the Advanced War School, receiving the rank of Captain upon graduation.][ In 1913, during the ]Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

against Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, Antonescu served as a staff officer in the First Cavalry Division in Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; bg, Добруджа, Dobrudzha or ''Dobrudža''; ro, Dobrogea, or ; tr, Dobruca) is a historical region in the Balkans that has been divided since the 19th century between the territories of Bulgaria and Romania. I ...

.[

]

World War I

After 1916, when Romania entered World War I on the Allied side, Ion Antonescu acted as chief of staff for General Constantin Prezan.

After 1916, when Romania entered World War I on the Allied side, Ion Antonescu acted as chief of staff for General Constantin Prezan.[ When enemy troops crossed the mountains from ]Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

into Wallachia, Antonescu was ordered to design a defense plan for Bucharest.[

The Romanian royal court, army, and administration were subsequently forced to retreat into ]Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

. Antonescu took part in an important decision involving defensive efforts, an unusual promotion which probably stoked his ambitions.[ In December, as Prezan became the Chief of the General Staff, Antonescu, who was by now a major, was named the head of operations, being involved in the defence of Moldavia. He contributed to the tactics used during the Battle of Mărășești (July–August 1917), when Romanians under General ]Eremia Grigorescu

Eremia Teofil Grigorescu (28 November 1863 – 21 July 1919) was a Romanian artillery general during World War I, and Minister of War in the Constantin Coandă cabinet (October–November 1918).

Early life

Born in 1863 in the village Golășe ...

managed to stop the advance of German forces under the command of Field Marshal August von Mackensen

Anton Ludwig Friedrich August von Mackensen (born Mackensen; 6 December 1849 – 8 November 1945), ennobled as "von Mackensen" in 1899, was a German field marshal. He commanded successfully during World War I of 1914–1918 and became one of ...

. Being described as "a talented if prickly individual", Antonescu lived in Prezan's proximity for the remainder of the war and influenced his decisions.[Deletant, p. 38] Such was the influence of Antonescu on General Prezan that General Alexandru Averescu used the formula "Prezan (Antonescu)" in his memoirs to denote Prezan's plans and actions.

That autumn, Romania's main ally, the Russian Provisional Government, left the conflict. Its successor, Bolshevik Russia, made peace with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

, leaving Romania the only enemy of the Central Powers on the Eastern Front. In these conditions, the Romanian government made its own peace treaty with the Central Powers. Romania broke the treaty later in the year, on the grounds that King Ferdinand I had not signed it. During the interval, Antonescu, who viewed the separate peace as "the most rational solution," was assigned command over a cavalry regiment.[ The renewed offensive played a part in ensuring the union of Transylvania with Romania. After the war, Antonescu's merits as an operations officer were noticed by, among others, politician Ion G. Duca, who wrote that "his ntonescu'sintelligence, skill and activity, brought credit on himself and invaluable service to the country."][ Another event occurring late in the war is also credited with having played a major part in Antonescu's life: in 1918, Crown Prince Carol (the future King Carol II) left his army posting to a commoner. This outraged Antonescu, who developed enduring contempt for the future king.][

]

Diplomatic assignments and General Staff positions

Lieutenant Colonel Ion Antonescu retained his visibility in the public eye during the interwar period. He participated in the political campaign to earn recognition at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 for Romania's gains in Transylvania. His nationalist argument about a future state was published as the essay ''Românii. Origina, trecutul, sacrificiile și drepturile lor'' ("The Romanians. Their Origin, Their Past, Their Sacrifices and Their Rights"). The booklet advocated extension of Romanian rule beyond the confines of

Lieutenant Colonel Ion Antonescu retained his visibility in the public eye during the interwar period. He participated in the political campaign to earn recognition at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 for Romania's gains in Transylvania. His nationalist argument about a future state was published as the essay ''Românii. Origina, trecutul, sacrificiile și drepturile lor'' ("The Romanians. Their Origin, Their Past, Their Sacrifices and Their Rights"). The booklet advocated extension of Romanian rule beyond the confines of Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creatio ...

, and recommended, at the risk of war with the emerging Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

, the annexation of all Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of ...

areas and the Timok Valley. Antonescu was known for his frequent and erratic changes of mood, going from being extremely angry to being calm to angry again to being calm again within minutes, behaviour that often disoriented those who had to work with him.Jean Ancel

Jean Ancel (1940 – 30 April 2008) was a Romanian-born Israeli author and historian; with specialty in the history of the Jews in Romania between the two World wars, and the Holocaust of the Jews of Romania.

Biography

Jean Ancel was born to Je ...

wrote that Antonescu's frequent changes of mood were due to the syphilis he contracted as a young man, a condition he suffered from for the rest of his life.Nicolae Titulescu

Nicolae Titulescu (; 4 March 1882 – 17 March 1941) was a Romanian diplomat, at various times government minister, finance and foreign minister, and for two terms president of the General Assembly of the League of Nations (1930–32).

Early ...

; the two became personal friends.[Deletant, p. 39.] He was also in contact with the Romanian-born conservative aristocrat and writer Marthe Bibesco

Princess Martha Bibescu (Martha Lucia; ''née'' Lahovary; 28 January 1886 – 28 November 1973) also known outside of Romania as Marthe Bibesco, was a celebrated Romanian-French writer, socialite, style icon and political hostess. She spent her c ...

, who introduced Antonescu to the ideas of Gustave Le Bon, a researcher of crowd psychology who had an influence on Fascism.[ Jaap van Ginneken, ''Crowds, Psychology, and Politics, 1871–1899'', ]Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

, Cambridge, 1992, p. 186. . Bibesco saw Antonescu as a new version of 19th century nationalist Frenchman Georges Boulanger, introducing him as such to Le Bon.[ In 1923, he made the acquaintance of lawyer Mihai Antonescu, who was to become his close friend, legal representative and political associate.

After returning to Romania in 1926, Antonescu resumed his teaching in Sibiu, and, in the autumn of 1928, became Secretary-General of the Defense Ministry in the ]Vintilă Brătianu

Vintilă Ion Constantin Brătianu (16 September 1867 – 22 December 1930) was a Romanian politician who served as Prime Minister of Romania between 24 November 1927 and 9 November 1928. He and his brothers Ion I. C. Brătianu and Dinu Brătianu ...

cabinet.[ He married Maria Niculescu, for long a resident of France, who had been married twice before: first to a Romanian Police officer, with whom she had a son, Gheorghe (died 1944), and then to a Frenchman of Jewish origin. After a period as Deputy Chief of the General Staff,][ he was appointed its Chief (1933–1934). These assignments coincided with the rule of Carol's underage son Michael I and his regents, and with Carol's seizure of power in 1930. During this period Antonescu first grew interested in the Iron Guard, an antisemitic and fascist-related movement headed by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. In his capacity as Deputy Chief of Staff, he ordered the Army's intelligence unit to compile a report on the faction, and made a series of critical notes on Codreanu's various statements.][

As Chief of Staff, Antonescu reportedly had his first confrontation with the political class and the monarch. His projects for weapon modernization were questioned by Defense Minister Paul Angelescu, leading Antonescu to present his resignation.][ According to another account, he completed an official report on the embezzlement of Army funds which indirectly implicated Carol and his '']camarilla

A camarilla is a group of courtiers or favourites who surround a king or ruler. Usually, they do not hold any office or have any official authority at the royal court but influence their ruler behind the scenes. Consequently, they also escape havi ...

'' (''see Škoda Affair'').[ The king consequently ordered him out of office, provoking indignation among sections of the political mainstream.][ On Carol's orders, Antonescu was placed under surveillance by the '' Siguranța Statului'' intelligence service, and closely monitored by the Interior Ministry Undersecretary Armand Călinescu.][Deletant, p. 40] The officer's political credentials were on the rise, as he was able to establish and maintain contacts with people on all sides of the political spectrum, while support for Carol plummeted. Among these were contacts with the two main democratic groups, the National Liberal and the National Peasants', parties known respectively as PNL and PNȚ.[ He was also engaged in discussions with the rising far right, antisemitic and fascist movements; although in competition with each other, both the National Christian Party (PNC) of Octavian Goga and the Iron Guard sought to attract Antonescu to their side.][ In 1936, to the authorities' alarm, Army General and Iron Guard member ]Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Grănicerul

Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Grănicerul was a Romanian landowner, general and far-right politician who was a member of the Iron Guard, and a member of the Legionary Senate.

Biography

Gheorghe Cantacuzino was born in Paris as the son of engineer I.G. C ...

arranged a meeting between Ion Antonescu and the movement's leader, Corneliu Codreanu. Antonescu is reported to have found Codreanu arrogant, but to have welcomed his revolutionizing approach to politics.[

]

Defense portfolio and the Codreanu trials

In late 1937, after the December general election came to an inconclusive result, Carol appointed Goga Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

over a far right cabinet that was the first executive to impose racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

in its treatment of the Jewish community. Goga's appointment was meant to curb the rise of the more popular and even more radical Codreanu. Initially given the Communications portfolio by his rival, Interior Minister Armand Călinescu, Antonescu repeatedly demanded the office of Defense Minister, which he was eventually granted. His mandate coincided with a troubled period, and saw Romania having to choose between its traditional alliance with France, Britain, the crumbling Little Entente

The Little Entente was an alliance formed in 1920 and 1921 by Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (since 1929 Yugoslavia) with the purpose of common defense against Hungarian revanchism and the prospect of a ...

and the League of Nations or moving closer to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and its Anti-Comintern Pact. Antonescu's own contribution is disputed by historians, who variously see him as either a supporter of the Anglo-French alliance or, like the PNC itself, more favourable to cooperation with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

's Germany.[ At the time, Antonescu viewed Romania's alliance with the Entente as insurance against Hungarian and ]Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

revanchism, but, as an anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

, he was suspicious of the Franco-Soviet rapprochement. Particularly concerned about Hungarian demands in Transylvania, he ordered the General Staff to prepare for a western attack. However, his major contribution in office was in relation to an internal crisis: as a response to violent clashes between the Iron Guard and the PNC's own fascist militia, the '' Lăncieri'', Antonescu extended the already imposed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

.

The Goga cabinet ended when the tentative rapprochement between Goga and Codreanu prompted Carol to overthrow the democratic system and proclaim his own authoritarian regime (''see 1938 Constitution of Romania, National Renaissance Front''). The deposed Premier died in 1938, while Antonescu remained a close friend of his widow, Veturia Goga.[Deletant, p. 70.] By that time, revising his earlier stance, Antonescu had also built a close relationship with Codreanu, and was even said to have become his confidant.[Deletant, p. 42][ Ilarion Țiu]

"Relațiile regimului autoritar al lui Carol al II-lea cu opoziția. Studiu de caz: arestarea conducerii Mișcării Legionare"

i

''Revista Erasmus''

14/2003-2005, at the University of Bucharest Faculty of History On Carol's request, he had earlier asked the Guard's leader to consider an alliance with the king, which Codreanu promptly refused in favour of negotiations with Goga, coupled with claims that he was not interested in political battles, an attitude supposedly induced by Antonescu himself.

Soon afterward, Călinescu, acting on indications from the monarch, arrested Codreanu and prosecuted him in two successive trials. Antonescu, whose mandate of Defense Minister had been prolonged under the premiership of Miron Cristea, resigned in protest of Codreanu's arrest.[Deletant, p. 44] Antonescu's mandate ended on 30 March 1938. He also served as Air and Marine Minister between 2 February and his resignation on 30 March. He was a celebrity defense witness at the latter's first[ and second trials.][ During the latter, which resulted in Codreanu's conviction for ]treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, Antonescu vouched for his friend's honesty while shaking his hand in front of the jury.[ Upon the conclusion of the trial, the king ordered his former minister interned at Predeal, before assigning him to command the Third Army in the remote eastern region of Bessarabia (and later removing him after Antonescu expressed sympathy for Guardists imprisoned in Chișinău). Attempting to discredit his rival, Carol also ordered Antonescu's wife to be tried for ]bigamy

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. ...

, based on a false claim that her divorce had not been finalized. Defended by Mihai Antonescu, the officer was able to prove his detractors wrong. Codreanu himself was taken into custody and discreetly killed by the Gendarmes acting on Carol's orders (November 1938).

Carol's regime slowly dissolved into crisis, a dissolution accelerated after the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, when the military success of the core Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

and the non-aggression pact signed by Germany and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

saw Romania isolated and threatened (''see Romania during World War II

Following the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, the Kingdom of Romania under King Carol II officially adopted a position of neutrality. However, the rapidly changing situation in Europe during 1940, as well as domestic political up ...

''). In 1940, two of Romania's regions, Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, were lost to a Soviet occupation consented to by the king. This came as Romania, exposed by the Fall of France, was seeking to align its policies with those of Germany. Ion Antonescu himself had come to value a pro-Axis alternative after the 1938 Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, when Germany imposed demands on Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

with the acquiescence of France and the United Kingdom, leaving locals to fear that, unless reoriented, Romania would follow. Angered by the territorial losses of 1940, General Antonescu sent Carol a general note of protest, and, as a result, was arrested and interned at Bistrița Monastery.[ While there, he commissioned Mihai Antonescu to establish contacts with Nazi German officials, promising to advance German economic interest, particularly in respect to the local oil industry, in exchange for endorsement. Commenting on Ion Antonescu's ambivalent stance, Hitler's minister to Romania, Wilhelm Fabricius, wrote to his superiors: "I am not convinced that he is a safe man."

]

Rise to power

Romania's elite had been intensely Francophile ever since Romania had won its independence in the 19th century, indeed so Francophile that the defeat of France in June 1940 had the effect of discrediting the entire elite. Antonescu's internment ended in August, during which interval, under Axis pressure, Romania had ceded Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria (''see Treaty of Craiova'') and Northern Transylvania to

Romania's elite had been intensely Francophile ever since Romania had won its independence in the 19th century, indeed so Francophile that the defeat of France in June 1940 had the effect of discrediting the entire elite. Antonescu's internment ended in August, during which interval, under Axis pressure, Romania had ceded Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria (''see Treaty of Craiova'') and Northern Transylvania to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

(''see Second Vienna Award''). The latter grant caused consternation among large sections of Romania's population, causing Carol's popularity to fall to a record low and provoking large-scale protests in Bucharest, the capital. These movements were organized competitively by the pro- Allied PNȚ, headed by Iuliu Maniu, and the pro-Nazi Iron Guard.[ The latter group had been revived under the leadership of Horia Sima, and was organizing a '']coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

''. In this troubled context, Antonescu simply left his assigned residence. He may have been secretly helped in this by German intercession, but was more directly aided to escape by socialite Alice Sturdza, who was acting on Maniu's request.[Deletant, p. 48] Antonescu subsequently met with Maniu in Ploiești

Ploiești ( , , ), formerly spelled Ploești, is a city and county seat in Prahova County, Romania. Part of the historical region of Muntenia, it is located north of Bucharest.

The area of Ploiești is around , and it borders the Blejoi commun ...

, where they discussed how best to manage the political situation.[ While these negotiations were carried out, the monarch himself was being advised by his entourage to recover legitimacy by governing in tandem with the increasingly popular Antonescu, while creating a new political majority from the existing forces.][ On 2 September 1940, Valer Pop, a courtier and an important member of the ''camarilla'', first advised Carol to appoint Antonescu as Prime Minister as the solution to the crisis. Pop's reasons for advising Carol to appoint Antonescu as Prime Minister were partly because Antonescu, who was known to be friendly with the Iron Guard and who had been imprisoned under Carol, was believed to have enough of an oppositional background to Carol's regime to appease the public and partly because Pop knew that Antonescu, for all his Legionary sympathies, was a member of the elite and believed he would never turn against it. When Carol proved reluctant to make Antonescu Prime Minister, Pop visited the German legation to meet with Fabricius on the night of 4 September 1940 to ask that the German minister phone Carol to tell him that the ''Reich'' wanted Antonescu as Prime Minister, and Fabricius's promptly did just that. Carol and Antonescu accepted the proposal, Antonescu being ordered to approach political party leaders Maniu of the PNȚ and Dinu Brătianu of the PNL.][ They all called for Carol's abdication as a preliminary measure,][ while Sima, another leader sought after for negotiations, could not be found in time to express his opinion.][ Antonescu partly complied with the request but also asked Carol to bestow upon him the reserve powers for Romanian heads of state.][ Carol yielded and, on 5 September 1940, the general became Prime Minister, and Carol transferred most of his dictatorial powers to him.][ The latter's first measure was to curtail potential resistance within the Army by relieving Bucharest Garrison chief Gheorghe Argeșanu of his position and replacing him with ]Dumitru Coroamă

Dumitru Coroamă (July 19, 1885 – 1956) was a Romanian soldier and fascist activist, who held the rank of major general of the Romanian Army during World War II.

He was especially known for his contribution to the 1940 establishment of the Nati ...

. Shortly afterward, Antonescu heard rumours that two of Carol's loyalist generals, Gheorghe Mihail

Gheorghe Mihail (March 13, 1887 – January 31, 1982) was a Romanian career army officer.

Born in Brăila, he completed primary school in 1902 and passed an examination to enter the school for soldiers' sons in Iași, taking years 7 and 8 there.N ...

and Paul Teodorescu, were planning to have him killed. In reaction, he forced Carol to abdicate, while General Coroamă was refusing to carry out the royal order of shooting down Iron Guardist protesters.

Michael ascended the throne for the second time, while Antonescu's dictatorial powers were confirmed and extended.[ On 6 September, the day Michael formally assumed the throne, he issued a royal decree declaring Antonescu '']Conducător

''Conducător'' (, "Leader") was the title used officially by Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu during World War II, also occasionally used in official discourse to refer to Carol II and Nicolae Ceaușescu.

History

The word is derived from the Ro ...

'' (leader) of the state. The same decree relegated the monarch to a ceremonial role. Among Antonescu's subsequent measures was ensuring the safe departure into self-exile of Carol and his mistress Elena Lupescu, granting protection to the royal train when it was attacked by armed members of the Iron Guard.[ The regime of King Carol had been notorious for being the most corrupt regime in Europe during the 1930s, and when Carol fled Romania, he took with him the better part of the Romanian treasury, leaving the new government with enormous financial problems.][Crampton, Richard ''Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century and After'', London: Routledge, 1997 pp. 117–118.] Antonescu had expected, perhaps naïvely, that Carol would take with him enough money to provide for a comfortable exile, and was surprised that Carol had cleared out almost the entire national treasury. For the next four years, a major concern of Antonescu's government was attempting to have the Swiss banks where Carol had deposited the assets return the money to Romania; this effort did not meet with success.[ and opted instead for a ]coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

between a military dictatorship lobby and the Iron Guard.[ He later justified his choice by stating that the Iron Guard "represented the political base of the country at the time." Right from the outset, Antonescu clashed with Sima over economic questions, with Antonescu's main concern being to get the economy growing so as to provide taxes for a treasury looted by Carol, while Sima favored populist economic measures that Antonescu insisted there was no money for.

]

Antonescu-Sima partnership

The resulting regime, deemed the '' National Legionary State'', was officially proclaimed on 14 September. On that date, the Iron Guard was remodelled into the only legally permitted party in Romania. Antonescu continued as Premier and ''Conducător'', and was named as the Guard's honorary commander. Sima became Deputy Premier and leader of the Guard.

The resulting regime, deemed the '' National Legionary State'', was officially proclaimed on 14 September. On that date, the Iron Guard was remodelled into the only legally permitted party in Romania. Antonescu continued as Premier and ''Conducător'', and was named as the Guard's honorary commander. Sima became Deputy Premier and leader of the Guard.[Peter Davies, Derek Lynch, ''The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right'', ]Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law ...

, London, 2002, p. 196. .Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

. Germans troops entered the country in stages, in order to defend the local oil industry and help instruct their Romanian counterparts on '' Blitzkrieg'' tactics. On 23 November, Antonescu was in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, where his signature sealed Romania's commitment to the main Axis instrument, the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

.[ Two days later, the country also adhered to the Nazi-led Anti-Comintern Pact. Other than these generic commitments, Romania had no treaty binding it to Germany, and the Romanian-German alliance functioned informally. Speaking in 1946, Antonescu claimed to have followed the pro-German path in continuation of earlier policies, and for fear of a Nazi ]protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

in Romania.

During the National Legionary State period, earlier antisemitic legislation was upheld and strengthened, while the " Romanianization" of Jewish-owned enterprises became standard official practice.[ Immediately after coming into office, Antonescu himself expanded the anti-Jewish and Nuremberg law-inspired legislation passed by his predecessors Goga and ]Ion Gigurtu

Ion Gigurtu (; 24 June 1886 – 24 November 1959) was a far-right Romanian politician, Land Forces officer, engineer and industrialist who served a brief term as Prime Minister from 4 July to 4 September 1940, under the personal regime of King Car ...

, while tens of new anti-Jewish regulations were passed in 1941–1942. This was done despite his formal pledge to Wilhelm Filderman

Wilhelm Filderman (last name also spelled Fieldermann; 14 November 1882 – 1963) was a lawyer and the leader of the Romanian-Jewish community between 1919 and 1947; in addition, he was a representative of the Jews in the Romanian parliament.

Ea ...

and the Jewish Communities Federation that, unless engaged in "sabotage," "the Jewish population will not suffer." Antonescu did not reject the application of Legionary policies, but was offended by Sima's advocacy of paramilitarism

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

and the Guard's frequent recourse to street violence.[ He drew much hostility from his partners by extending some protection to former dignitaries whom the Iron Guard had arrested. One early incident opposed Antonescu to the Guard's magazine '' Buna Vestire'', which accused him of leniency and was subsequently forced to change its editorial board. By then, the Legionary press was routinely claiming that he was obstructing revolution and aiming to take control of the Iron Guard, and that he had been transformed into a tool of ]Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

(''see Anti-Masonry''). The political conflict coincided with major social challenges, including the influx of refugees from areas lost earlier in the year and a large-scale earthquake affecting Bucharest.

Disorder peaked in the last days of November 1940, when, after uncovering the circumstances of Codreanu's death, the fascist movement ordered retaliations against political figures previously associated with Carol, carrying out the Jilava Massacre, the assassinations of Nicolae Iorga and Virgil Madgearu, and several other acts of violence.[ As retaliation for this insubordination, Antonescu ordered the Army to resume control of the streets, unsuccessfully pressured Sima to have the assassins detained, ousted the Iron Guardist prefect of Bucharest ]Police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

Ștefan Zăvoianu, and ordered Legionary ministers to swear an oath to the ''Conducător''. His condemnation of the killings was nevertheless limited and discreet, and, the same month, he joined Sima at a burial ceremony for Codreanu's newly discovered remains. The widening gap between the dictator and Sima's party resonated in Berlin. When, in December, Legionary Foreign Minister Mihail R. Sturdza obtained the replacement of Fabricius with Manfred Freiherr von Killinger

Manfred Freiherr von Killinger (July 14, 1886 – September 2, 1944) was a German naval officer, ''Freikorps'' leader, military writer and Nazi politician. A veteran of World War I and member of the ''Marinebrigade Ehrhardt'' during the Germa ...

, perceived as more sympathetic to the Iron Guard, Antonescu promptly took over leadership of the ministry, with the compliant diplomat Constantin Greceanu

Constantin is an Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Romanian male given name. It can also be a surname.

For a list of notable people called Constantin, see Constantine (name).

See also

* Constantine (name)

* Konstantin

The first name Konsta ...

as his right hand. In Germany, such leaders of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

as Heinrich Himmler, Baldur von Schirach

Baldur Benedikt von Schirach (9 May 1907 – 8 August 1974) was a German politician who is best known for his role as the Nazi Party national youth leader and head of the Hitler Youth from 1931 to 1940. He later served as ''Gauleiter'' and ''Re ...

and Joseph Goebbels threw their support behind the Legionaries,[ whereas Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and the ]Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

stood by Antonescu.[ The latter group was concerned that any internal conflict would threaten Romania's oil industry, vital to the German war effort.][ The German leadership was by then secretly organizing '']Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

'', the attack on the Soviet Union.[Delia Radu]

"Serialul 'Ion Antonescu și asumarea istoriei' (2)"

BBC, Romanian edition, 1 August 2008.

Legionary Rebellion and Operation Barbarossa

Antonescu's plan to act against his coalition partners in the event of further disorder hinged on Hitler's approval,

Antonescu's plan to act against his coalition partners in the event of further disorder hinged on Hitler's approval,[D. S. Lewis, ''Illusions of Grandeur: Mosley, Fascism and British Society, 1931–81'', Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1987, p. 228. .] a vague signal of which had been given during ceremonies confirming Romania's adherence to the Tripartite Pact.[ A decisive turn occurred when Hitler invited Antonescu and Sima both over for discussions: whereas Antonescu agreed, Sima stayed behind in Romania, probably plotting a ''coup d'état''.][ While Hitler did not produce a clear endorsement for clamping down on Sima's party, he made remarks interpreted by their recipient as oblique blessings. On 14 January 1941 during a German-Romanian summit, Hitler informed Antonescu of his plans to invade the Soviet Union later that year and asked Romania to participate.][Ancel, Jean "Antonescu and the Jews" pp. 463–479 from ''The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Reexamined'' edited by Michael Berenbaum and Abraham Peck, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998 p. 466.] By this time, Hitler had come to the conclusion that while Sima was ideologically closer to him, Antonescu was the more competent leader capable of ensuring stability in Romania while being committed to aligning his country with the Axis.

The Antonescu-Sima dispute erupted into violence in January 1941, when the Iron Guard instigated a series of attacks on public institutions and a pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

, incidents collectively known as the "Legionary Rebellion

Between 21 and 23 January 1941, a rebellion of the Iron Guard paramilitary organization, whose members were known as Legionnaires, occurred in Bucharest, Romania. As their privileges were being gradually removed by the ''Conducător'' Ion An ...

."[ This came after the mysterious assassination of Major Döring, a German agent in Bucharest, which was used by the Iron Guard as a pretext to accuse the ''Conducător'' of having a secret anti-German agenda, and made Antonescu oust the Legionary Interior Minister, ]Constantin Petrovicescu

Constantin Petrovicescu (; October 22, 1883 – September 8, 1949) was a Romanian soldier and politician, who served as Interior Minister from September 14, 1940 to January 21, 1941 during the National Legionary State.

A sympathizer and sec ...

, while closing down all of the Legionary-controlled "Romanianization" offices. Various other clashes prompted him to demand the resignation of all Police commanders who sympathized with the movement. After two days of widespread violence, during which Guardists killed some 120 Bucharest Jews,[ Antonescu sent in the Army, under the command of General Constantin Sănătescu.][ German officials acting on Hitler's orders, including the new Ambassador ]Manfred Freiherr von Killinger

Manfred Freiherr von Killinger (July 14, 1886 – September 2, 1944) was a German naval officer, ''Freikorps'' leader, military writer and Nazi politician. A veteran of World War I and member of the ''Marinebrigade Ehrhardt'' during the Germa ...

, helped Antonescu eliminate the Iron Guardists, but several of their lower-level colleagues actively aided Sima's subordinates. Goebbels was especially upset by the decision to support Antonescu, believing it to have been advantageous to "the Freemasons."

After the purge of the Iron Guard, Hitler kept his options open by granting political asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another entit ...

to Sima—whom Antonescu's courts sentenced to death—and to other Legionaries in similar situations. The Guardists were detained in special conditions at Buchenwald and Dachau

Dachau () was the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents which consisted of: communists, social democrats, and other dissidents. It is lo ...

concentration camps. In parallel, Antonescu publicly obtained the cooperation of ''Codreanists'', members of an Iron Guardist wing which had virulently opposed Sima, and whose leader was Codreanu's father Ion Zelea Codreanu. Antonescu again sought backing from the PNȚ and PNL to form a national cabinet, but his rejection of parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of t ...

made the two groups refuse him.

Antonescu traveled to Germany and met Hitler on eight more occasions between June 1941 and August 1944. Such close contacts helped cement an enduring relationship between the two dictators, and Hitler reportedly came to see Antonescu as the only trustworthy person in Romania,[Deletant, p. 62.] and the only foreigner to consult on military matters. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote that Hitler after first meeting Antonescu "...was greatly impressed by him; no other leader Hitler met other than Mussolini ever received such consistently favourable comments from the German dictator. Hitler even mustered the patience to listen to Antonescu's lengthy disquisitions on the glorious history of Romania and the perfidy of the Hungarians—a curious reversal for a man who was more accustomed to regaling visitors with tirades of his own." In later statements, Hitler offered praise to Antonescu's "breadth of vision" and "real personality."[Harvey, p. 498.] A remarkable aspect of the Hitler-Antonescu friendship was neither could speak others' language. Hitler only knew German while the only foreign language Antonescu knew was French, in which he was completely fluent. During their meetings, Antonescu spoke in French which was then translated into German by Hitler's translator Paul Schmidt and vice versa since Schmidt did not speak Romanian either. The German military presence increased significantly in early 1941, when, using Romania as a base, Hitler invaded the rebellious Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece ( grc, label= Greek, Βασίλειον τῆς Ἑλλάδος ) was established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople, wh ...

(''see Balkans Campaign''). In parallel, Romania's relationship with the United Kingdom, at the time the only major adversary of Nazi Germany, erupted into conflict: on 10 February 1941, British Premier Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

recalled His Majesty's Ambassador Reginald Hoare, and approved the blockade of Romanian ships in British-controlled ports. On 12 June 1941, during another summit with Hitler, Antonescu first learned of the "special" nature of Operation Barbarossa, namely, that the war against the Soviet Union was to be an ideological war to "annihilate" the forces of "Judeo-Bolshevism," a "war of extermination" to be fought without any mercy; Hitler even showed Antonescu a copy of the "Guidelines for the Conduct of the Troops in Russia" he had issued to his forces about the "special treatment" to be handed out to Soviet Jews.[Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, pp. 325–326] Besides anti-Semitism, there was an extremely strong current of anti-Slavic and anti-Asian racism to Antonescu's remarks about the "Asiatic hordes" of the Red Army.[Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, p. 325] The Asians Antonescu referred were the various Asian peoples of the Soviet Union, such as the Kazakhs, Kalmyks, Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, Uzbeks, Buryats, etc. During his summit with Hitler in June 1941, Antonescu told the ''Führer'' that he believed it was necessary to "once and for all" eliminate Russia as a power because the Russians were the most powerful Slavic nation and that as a Latin people, the Romanians had an inborn hatred of all Slavs and Jews. In June of that year, Romania joined the attack on the Soviet Union, led by Germany in coalition with Hungary,

In June of that year, Romania joined the attack on the Soviet Union, led by Germany in coalition with Hungary, Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

, the State of Slovakia, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, and the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

. Antonescu had been made aware of the plan by German envoys, and supported it enthusiastically even before Hitler extended Romania an offer to participate. On 18 June 1941, Antonescu gave orders to his generals about "cleansing the ground" of Jews when Romanian forces entered Bessarabia and Bukovina.[Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, p. 437.] Reflecting Antonescu's anti-Slavic feelings, despite the fact that the war was billed as a "crusade" in defence of Orthodoxy against "Judeo-Bolshevism", the war was not presented as a struggle to liberate the Orthodox Russians and Ukrainians from Communism; instead rule by "Judeo-Bolshevism" was portrayed as something brought about the innate moral inferiority of the Slavs, who thus needed to be ruled by the Germans and the Romanians.[ Antonescu had followed a generation of younger right-wing Romanian intellectuals led by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu who in the 1920s–30s had rejected the traditional Francophila of the Romanian elites and their adherence to Western notions of universal democratic values and human rights. Antonescu made it clear that his regime rejected the moral principles of the "demo-liberal world" and he saw the war as an ideological struggle between his spiritually pure "national-totalitarian regime" vs. "Jewish morality".][Ancel, Jean "Antonescu and the Jews" pp. 463–479 from ''The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Reexamined'' edited by Michael Berenbaum and Abraham Peck, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998 p. 467.] Antonescu believed that the liberal humanist-democratic-capitalist values of the West and Communism were both invented by the Jews to destroy Romania.[Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, pp. 438–439] Since the Jewish women were going to exterminated anyway, Antonescu felt there was nothing wrong about letting his soldiers and gendarmes have "some fun" before shooting them.Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

city of Berdychiv

Berdychiv ( uk, Берди́чів, ; pl, Berdyczów; yi, באַרדיטשעװ, Barditshev; russian: Берди́чев, Berdichev) is a historic city in the Zhytomyr Oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center ...

, Ion Antonescu was promoted to Marshal of Romania by royal decree on 22 August, in recognition for his role in restoring the eastern frontiers of Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creatio ...

.[Deletant, pp. 83, 86, 280, 305] In a report to Berlin, a German diplomat wrote that Marshal Antonescu had syphilis and that "among omaniancavalry officers this disease is as widespread as a common cold is among German officers. The Marshal suffers from severe attacks of it every several months."Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and t ...

—that is, beyond territory that had been part of Romania between the wars—and thrust deeper into Soviet territory, thus waging a war of aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor sanc ...

.[ On 30 August, Romania occupied a territory it deemed " Transnistria", formerly a part of the ]Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

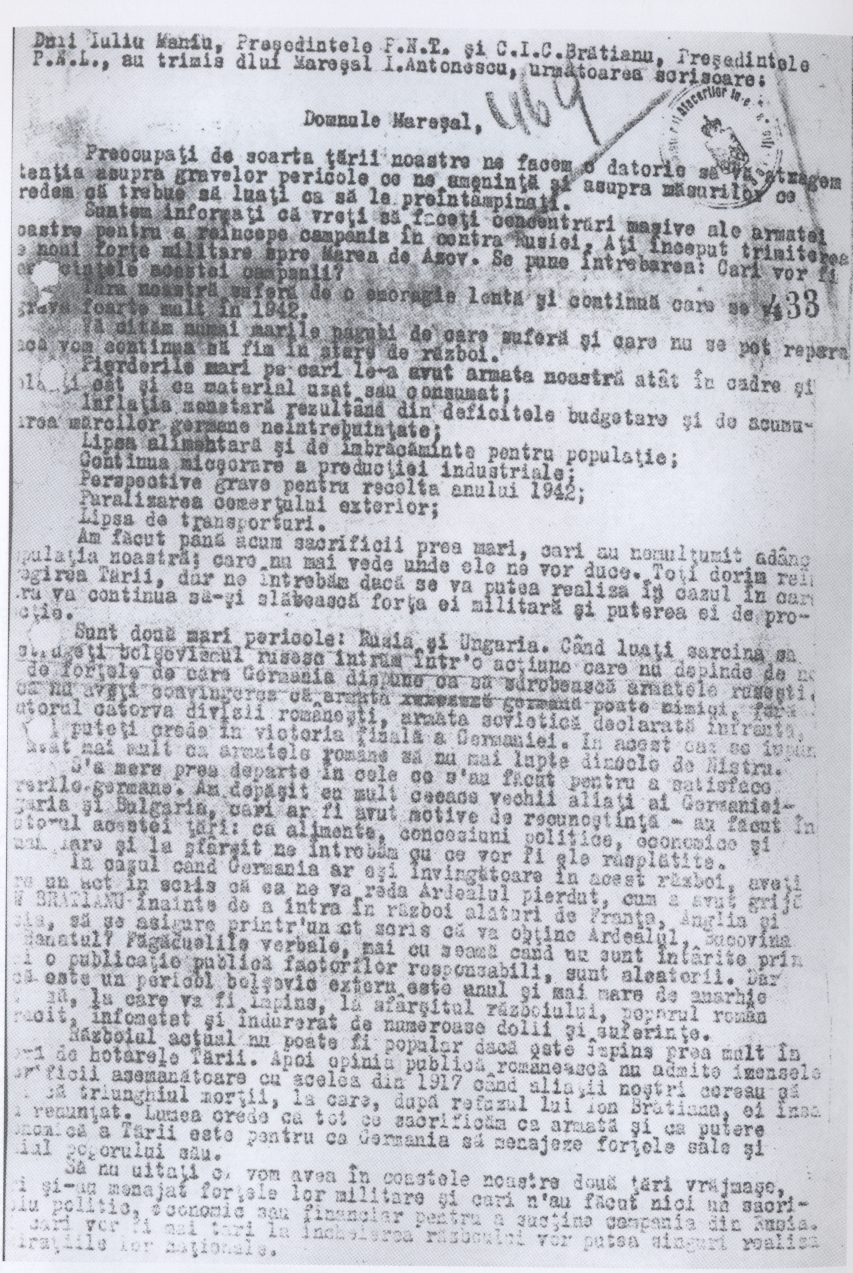

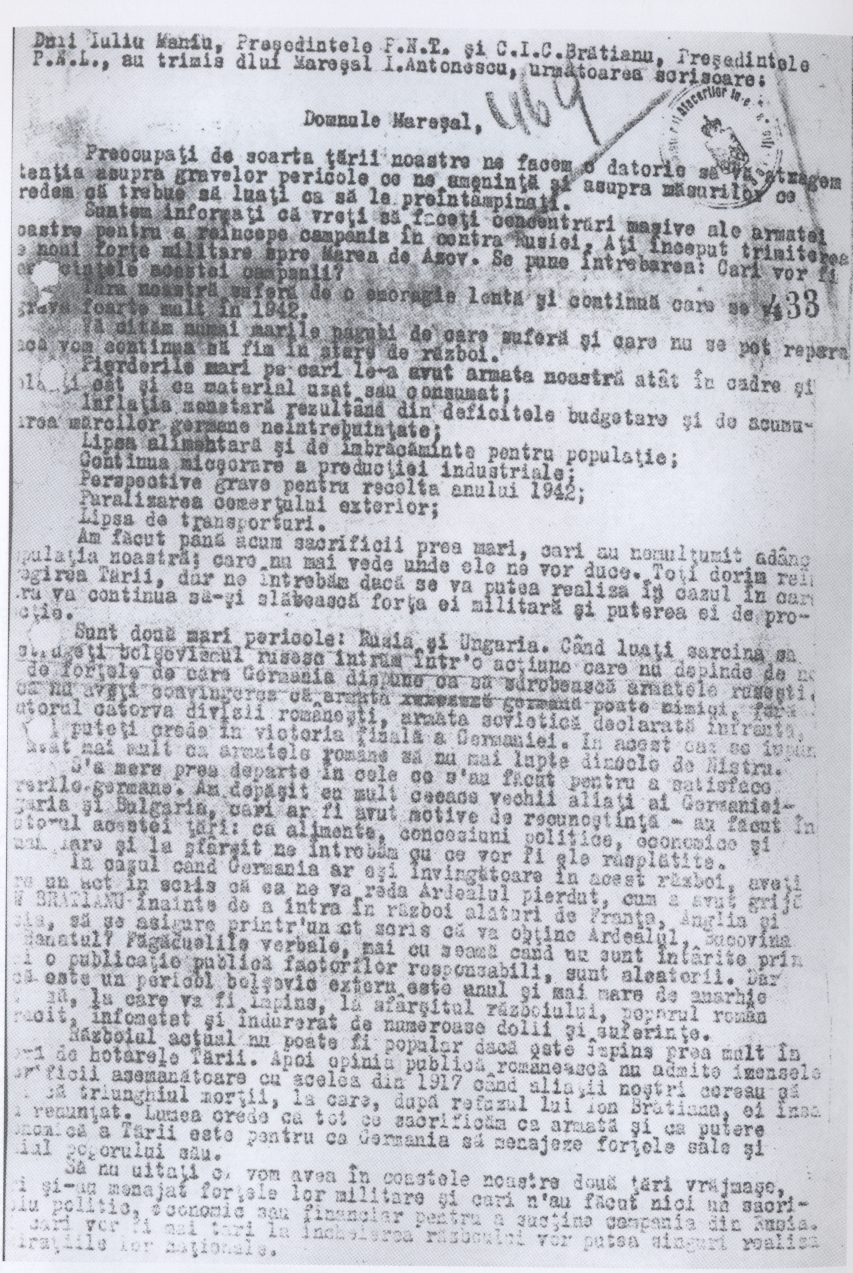

(including the entire Moldavian ASSR and further territories).[ Like the decision to continue the war beyond Bessarabia, this earned Antonescu much criticism from the semi-clandestine PNL and PNȚ.][ Insofar as the war against the Soviet Union was a war to recover Bessarabia and northern Bukovina – both regions that been a part of Romania until June 1940 and that had Romanian majorities – the conflict had been very popular with the Romanian public opinion.][Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, pp. 334–335.] But the idea of conquering Transnistria was not as that region had never been part of Romania, and a minority of the people were ethnic Romanian.Gheorghe Alexianu

Gheorghe Alexianu (born January 1, 1897, Străoane, Putna County; died 1 June 1946, Jilava) was a lawyer, high school teacher and associate professor who served as governor of Transnistria between 1941 and 1944. In 1946, he was accused and co ...

and became the site for the main component of the Holocaust in Romania

The history of the Jews in Romania concerns the Jews both of Romania and of Romanian origins, from their first mention on what is present-day Romanian territory. Minimal until the 18th century, the size of the Jewish population increased after ...

: a mass deportation of the Bessarabian and Ukrainian Jews, followed later by transports of Romani Romanians and Jews from Moldavia proper (that is, the portions of Moldavia west of the Prut).

The accord over Transnistria's administration, signed in Tighina

Bender (, Moldovan Cyrillic: Бендер) or Bendery (russian: Бендеры, , uk, Бендери), also known as Tighina ( ro, Tighina), is a city within the internationally recognized borders of Moldova under ''de facto'' control of the un ...

, also placed areas between the Dniester and the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

under Romanian military occupation, while granting control over all resources to Germany. In September 1941, Antonescu ordered Romanian forces to take Odessa, a prize he badly wanted for reasons of prestige. Russians had traditionally been seen in Romania as brutal aggressors, and for Romanian forces to take a major Soviet city and one of the largest Black Sea ports like Odessa would be a sign of how far Romania had been "regenerated" under Antonescu's leadership. Much to Antonescu's intense fury, the Red Army were able to halt the Romanian offensive on Odessa and 24 September 1941 Antonescu had to reluctantly ask for the help of the Wehrmacht with the drive on Odessa.[Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, p. 335.] On 16 October 1941 Odessa fell to the German-Romanian forces. The Romanian losses had been so heavy that the area around Odessa was known to the Romanian Army as the Vale of Tears.Wilhelm Filderman

Wilhelm Filderman (last name also spelled Fieldermann; 14 November 1882 – 1963) was a lawyer and the leader of the Romanian-Jewish community between 1919 and 1947; in addition, he was a representative of the Jews in the Romanian parliament.

Ea ...

wrote a letter to Antonescu complaining about the murder of Jews in Odessa, Antonescu wrote back: "Your Jews, who have become Soviet commissars, are driving Soviet soldiers in the Odessa region into a futile bloodbath, through horrendous terror techniques as the Russian prisoners themselves have admitted, simply to cause us heavy losses".[Ancel, Jean ''The History of the Holocaust in Romania'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011, pp. 459–460.] This veto was largely motivated by bureaucratic politics, namely if Antonescu exterminated all of the Jews of Romania himself, there would be nothing for the SS and the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' to do.

Reversal of fortunes

The Romanian Army's inferior arms, insufficient armour and lack of training had been major concerns for the German commanders since before the start of the operation. One of the earliest major obstacles Antonescu encountered on the Eastern Front was the resistance of Odessa, a Soviet port on the

The Romanian Army's inferior arms, insufficient armour and lack of training had been major concerns for the German commanders since before the start of the operation. One of the earliest major obstacles Antonescu encountered on the Eastern Front was the resistance of Odessa, a Soviet port on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

. Refusing any German assistance, he ordered the Romanian Army to maintain a two-month siege on heavily fortified and well-defended positions.[ The ill-equipped 4th Army suffered losses of some 100,000 men. Antonescu's popularity again rose in October, when the fall of Odessa was celebrated triumphantly with a parade through Bucharest's '']Arcul de Triumf

The Arcul de Triumf (Romanian; "Triumphal Arch") is a triumphal arch located in the northern part of Bucharest, Romania, on the Kiseleff Road.

The first, wooden, triumphal arch was built hurriedly, after Romania gained its independence (18 ...

'', and when many Romanians reportedly believed the war was as good as won.[ In Odessa itself, the aftermath included a large-scale massacre of the Jewish population, ordered by the Marshal as retaliation for a bombing which killed a number of Romanian officers and soldiers (General Ioan Glogojeanu among them).][ The city subsequently became the administrative capital of Transnistria.][ According to one account, the Romanian administration planned to change Odessa's name to ''Antonescu''. Antonescu's planned that once the war against the Soviet Union was won to invade Hungary to take back Transylvania and Bulgaria to take back the Dobruja with Antonescu being especially keen on the former.][Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 p. 521.] Antonescu planned on attacking Hungary to recover Transylvania at the first opportunity and regarded Romanian involvement on the Eastern Front in part as a way of proving to Hitler that Romania was a better German ally than Hungary, and thus deserving of German support when the planned Romanian-Hungarian war began.Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

and Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

.

As the Soviet Union recovered from the initial shock and slowed down the Axis offensive at the Battle of Moscow (October 1941 – January 1942), Romania was asked by its allies to contribute a larger number of troops.[Delia Radu]

"Serialul 'Ion Antonescu și asumarea istoriei' (3)"

BBC, Romanian edition, 1 August 2008. A decisive factor in Antonescu's compliance with the request appears to have been a special visit to Bucharest by Wehrmacht chief of staff Wilhelm Keitel, who introduced the ''Conducător'' to Hitler's plan for attacking the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

(''see Battle of the Caucasus'').[ The Romanian force engaged in the war reportedly exceeded German demands.][ It came to around 500,000 troops][Deletant, p. 2] and thirty actively involved divisions. As a sign of his satisfaction, Hitler presented his Romanian counterpart with a luxury car.[ On 7 December 1941, after reflecting on the possibility for Romania, Hungary and Finland to change their stance, the British government responded to repeated Soviet requests and declared war on all three countries. Following ]Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

's attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

and in compliance with its Axis commitment, Romania declared war on the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

within five days. These developments contrasted with Antonescu's own statement of 7 December: "I am an ally of the erman Erman Rašiti may refer to:

Given name

* Erman Bulucu (born 1989), Turkish footballer

* Erman Eltemur (born 1993), Turkish karateka

* Erman Güraçar (born 1974), Turkish footballer

* Erman Kılıç (born 1983), Turkish footballer

* Erman Kunter (b ...

Reich against he Soviet Union I am neutral in the conflict between Great Britain and Germany. I am for America against the Japanese."[Deletant, p. 92]

A crucial change in the war came with the Battle of Stalingrad in June 1942 – February 1943, a major defeat for the Axis. Romania's armies alone lost some 150,000 men (either dead, wounded or captured)[ and more than half of the country's divisions were wiped out.

The loss of two entire Romanian armies who all either killed or captured by the Soviets produced a major crisis in German-Romanian relations in the winter of 1943 with many people in the Romanian government for the first time questioning the wisdom of fighting on the side of the Axis.][Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 pp. 460–461.] Outside of the elites, by 1943 the continuing heavy losses on the Eastern Front, anger at the contempt which the Wehrmacht treated their Romanian allies and declining living standards within Romania made the war unpopular with the Romanian people, and consequently the ''Conducător'' himself. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote that: "The string of broken German promises of equipment and support, the disregard of warnings about Soviet offensive preparations, the unfriendly treatment of retreating Romanian units by German officers and soldiers and the general German tendency to blame their own miscalculations and disasters on their allies all combined to produce a real crisis in German-Romanian relations."syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

he had contracted earlier in life. He is known to have been suffering from digestive problems, treating himself with food prepared by Marlene von Exner, an Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n-born dietitian

A dietitian, medical dietitian, or dietician is an expert in identifying and treating disease-related malnutrition and in conducting medical nutrition therapy, for example designing an enteral tube feeding regimen or mitigating the effects of ...

who moved into Hitler's service after 1943.

Upon his return, Antonescu blamed the Romanian losses on German overseer Arthur Hauffe, whom Hitler agreed to replace. In parallel with the military losses, Romania was confronted with large-scale economic problems. Romania's oil was the ''Reichs only source of natural oil after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 to August 1944 (Germany also had synthetic oil plants operating from 1942 onwards), and as such for economic reasons, Romania was always treated as a major ally by Hitler.

Upon his return, Antonescu blamed the Romanian losses on German overseer Arthur Hauffe, whom Hitler agreed to replace. In parallel with the military losses, Romania was confronted with large-scale economic problems. Romania's oil was the ''Reichs only source of natural oil after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 to August 1944 (Germany also had synthetic oil plants operating from 1942 onwards), and as such for economic reasons, Romania was always treated as a major ally by Hitler.Operation Tidal Wave

Operation Tidal Wave was an air attack by bombers of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) based in Libya on nine oil refineries around Ploiești, Romania on 1 August 1943, during World War II. It was a strategic bombing mission and part o ...

''). Official sources from the following period amalgamate military and civilian losses of all kinds, which produces a total of 554,000 victims of the war. To improve the Romanian army's effectiveness, the Mareșal tank destroyer was developed starting in late 1942. Marshal Antonescu, after whom the vehicle was named, was involved in the project himself. The vehicle later influenced the development of the German Hetzer.

In this context, the Romanian leader acknowledged that Germany was losing the war, and he therefore authorized his Deputy Premier and new Foreign Minister Mihai Antonescu to set up contacts with the Allies.[ In early 1943, Antonescu authorized his diplomats to contact British and American diplomats in Portugal and Switzerland to see if were possible for Romania to sign an armistice with the Western powers.][Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 p. 461.] The Romanian diplomats were informed that no armistice was possible until an armistice was signed with the Soviet Union, a condition Antonescu rejected.[ The discussions were strained by the Western Allies' call for an unconditional surrender, over which the Romanian envoys bargained with Allied diplomats in ]Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...