Information Research Department on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Information Research Department (IRD) was a secret

To further promote ''Animal Farm'', the IRD commissioned cartoon strips to be planted in newspapers across the globe. The foreign rights to distribute these cartoons were acquired by the IRD for Cyprus, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Nigeria, Trinidad, Jamaica, Fiji, British Guiana and British Honduras.

To further promote ''Animal Farm'', the IRD commissioned cartoon strips to be planted in newspapers across the globe. The foreign rights to distribute these cartoons were acquired by the IRD for Cyprus, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Nigeria, Trinidad, Jamaica, Fiji, British Guiana and British Honduras.

The existence of Orwell's List, also known as Foreign Office File "FO/111/189", was made public in 1996. The names included on the list were not made public until 2003. The list came into possession of the IRD in 1949, after being collected by IRD agent Celia Kirwan. Kirwan was a close friend of Orwell, she was also Arthur Koestler's sister-in-law and the secretary for fellow IRD agent Robert Conquest. Guy Burgess was based in the next office to her own. The list itself was divided into three columns headed "Name" "Job" and "Remarks", and referred to those listed as "FTs" meaning Fellow Travelers, and labelled people he believed of being suspected of being secret Marxists as "cryptos". Some of the names listed by Orwell included filmmaker

The existence of Orwell's List, also known as Foreign Office File "FO/111/189", was made public in 1996. The names included on the list were not made public until 2003. The list came into possession of the IRD in 1949, after being collected by IRD agent Celia Kirwan. Kirwan was a close friend of Orwell, she was also Arthur Koestler's sister-in-law and the secretary for fellow IRD agent Robert Conquest. Guy Burgess was based in the next office to her own. The list itself was divided into three columns headed "Name" "Job" and "Remarks", and referred to those listed as "FTs" meaning Fellow Travelers, and labelled people he believed of being suspected of being secret Marxists as "cryptos". Some of the names listed by Orwell included filmmaker

Facsimile of page (PDF)

* * * * * * * * * {{cite journal , last=Wilford , first=Hugh , date=1998 , title=The Information Research Department: Britain's Secret Cold War Weapon Revealed , url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097531 , journal=Review of International Studies , volume=24 , issue=3 , pages=353–369 , doi=10.1017/S0260210598003532 , jstor=20097531, s2cid=145286473 , via=JSTORE , url-access=subscription Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Cold War propaganda Government agencies established in 1948 1977 disestablishments in the United Kingdom British propaganda organisations Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations 1948 establishments in the United Kingdom George Orwell Anti-communist propaganda Anti-communist organizations in the United Kingdom News agencies based in the United Kingdom Defunct United Kingdom intelligence agencies

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

propaganda department of the British Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

, created to publish anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

propaganda, including black propaganda, provide support and information to anti-communist politicians, academics, and writers, and to use weaponised information, but also disinformation and "fake news

Fake news or information disorder is false or misleading information (misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and hoaxes) claiming the aesthetics and legitimacy of news. Fake news often has the aim of damaging the reputation of a person ...

", to attack not only its original targets but also certain socialists and anti-colonial movements. Soon after its creation, the IRD broke away from focusing solely on Soviet matters and began to publish pro-colonial propaganda intended to suppress pro-independence revolutions in Asia, Africa, Ireland, and the Middle East. The IRD was heavily involved in the publishing of books, newspapers, leaflets and journals, and even created publishing houses to act as propaganda fronts, such as Ampersand Limited. Operating for 29 years, the IRD is known as the longest-running covert government propaganda department in British history, the largest branch of the Foreign Office, and the first major anglophone propaganda offensive against the USSR since the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. By the 1970s, the IRD was performing military intelligence tasks for the British Military in Northern Ireland during The Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

.

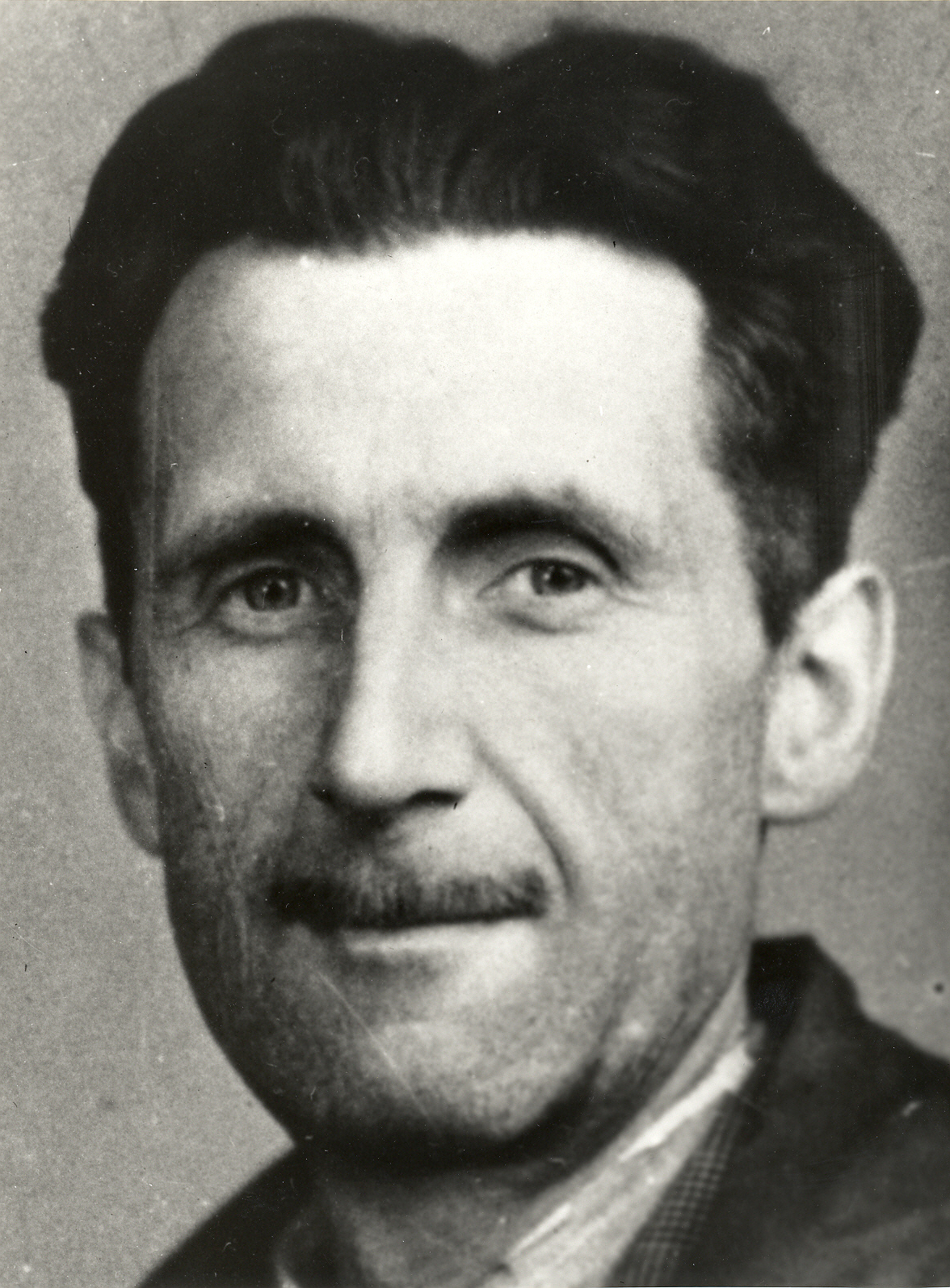

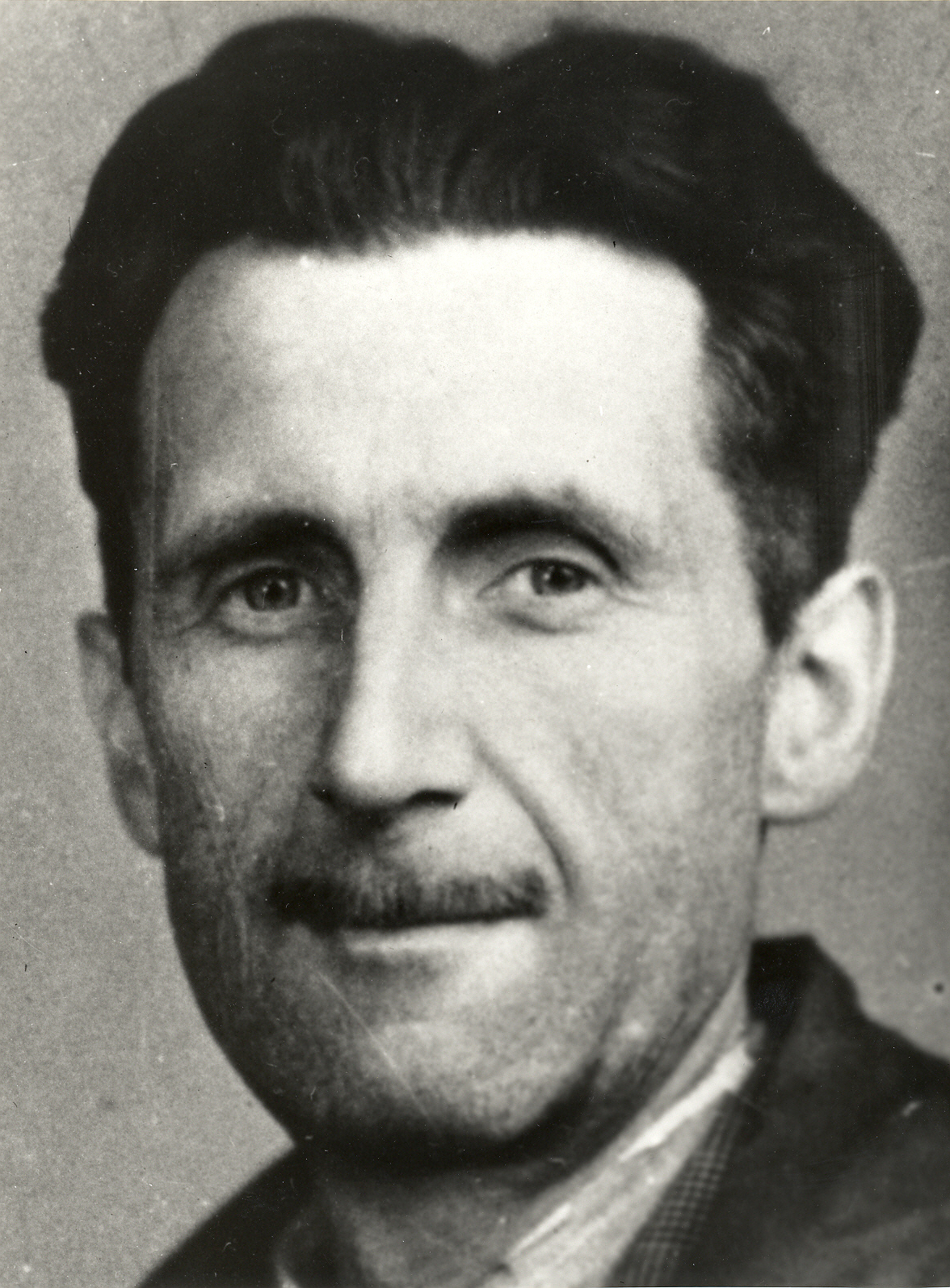

The IRD promoted works by many presumably anti-communist authors including George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler (, ; ; ; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest, and was educated in Austria, apart from his early school years. In 1931, Koestler j ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, and Robert Conquest.

Internationally, the IRD took part in many historic events, including Britain's entry into the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

, the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

, the Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War, was a guerrilla warfare, guerrilla war fought in Federation of Malaya, Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Arm ...

, The Troubles, the Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960), also known as the Mau Mau uprising, Mau Mau revolt, or Kenya Emergency, was a war in the British Kenya Colony (1920–1963) between the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), also known as the Mau Mau, and the ...

, Cyprus Emergency

The Cyprus Emergency was a conflict fought in British Cyprus between April 1955 and March 1959.

The National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA), a Greek Cypriot right-wing nationalist guerrilla organisation, began an armed campaign in s ...

, and the Sino-Indian War. Other IRD activities included forging letters and posters, conducting smear attacks against British trade unionists, and attacking opponents of the British military by planting fake news stories in the British press. Some of the fabricated stories the IRD created included accusations that Irish republicans were killing dogs by setting them on fire and falsely accusing members of EOKA, also anti-communist, of raping schoolgirls.

Although the existence of the IRD was successfully kept hidden from the British public until the 1970s, the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

had always been aware of its existence, for Guy Burgess had been posted to the IRD for a period of two months in 1948. Burgess was later sacked by the IRD's founder Christopher Mayhew, who accused him of being "dirty, drunk and idle". The IRD closed its operations in 1977 after its existence was discovered by British journalists after an investigation into a heavy amount of anti-Soviet propaganda being published by academics belonging to St Antony's College, Oxford. An exposé by David Leigh published in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', entitled "Death of the Department that Never Was", became the first public acknowledgement of the IRD's existence.

Origins

Since 1946, many senior officials of both theForeign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

and the right of the Labour Party had proposed the creation of an anti-communist propaganda organ. Christopher Warner raised a formal proposal in April 1946, but Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs may refer to:

* Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (Spain)

*Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (UK)

The secretary of state for foreign, commonwealth and development affairs, also known as the fore ...

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union from 1922 to 1940 and ...

was reluctant to upset the pro-Soviet members of the Labour Party. Later in the summer, Bevin rejected another proposal by Ivone Kirkpatrick to set up an anti-communist propaganda unit. In 1947, Christopher Mayhew lobbied for the proposals, linking anti-communism with the concept of "Third Force", which was meant to be a progressive camp between the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. This framing, together with anti-British Soviet propaganda attacks during the same years, led Bevin to change his position and to start discussing the details for the creation of a propaganda unit. After sending a confidential paper to the foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, in 1947, Mayhew was summoned by Attlee to Chequers

Chequers ( ) is the English country house, country house of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. A 16th-century manor house in origin, it is near the village of Ellesborough in England, halfway betwee ...

to discuss it further.

On 8 January 1948, the Cabinet of the United Kingdom

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the senior decision-making body of the Government of the United Kingdom. A committee of the Privy Council (United Kingdom), Privy Council, it is chaired by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Prime M ...

adopted the ''Future Foreign Publicity'', memorandum drafted by Christopher Mayhew and signed by Ernest Bevin. The memorandum embraced anti-communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

and took upon the British Labour Government to lead anti-communist progressivism internationally, stating:

To achieve these goals, the memorandum called for the establishment of a Foreign Office department "to collect information" about Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and to "provide material for our anti-Communist publicity through our Missions and Information Services abroad". The department would collaborate with ministers, British delegates, the Labour Party, trade union representatives, the Central Office of Information, and the BBC Overseas Service. The new department was finally established as the Information Research Department. Mayhew ran the department with Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick until 1950. The original offices were in Carlton House Terrace

Carlton House Terrace is a street in the St James's district of the City of Westminster in London. Its principal architectural feature is a pair of terraces, the Western and Eastern terraces, of white stucco-faced houses on the south side of ...

, before moving to Riverwalk House, Millbank

Millbank is an area of central London in the City of Westminster. Millbank is located by the River Thames, east of Pimlico and south of Westminster. Millbank is known as the location of major government offices, Burberry headquarters, the Mill ...

, London.

Staff and collaborators

The IRD was once one of the largest and well-funded organisations of the UK Foreign Office, with an estimated 400-600 employees at its height. The IRD founded under Clement Attlee's post-WWII Labour Party government (1945-1951) was headed by career civil servants including Ralph Murray, John Rennie, and Ray Whitney who became a Conservative MP and minister. Although the vast majority of IRD staff were British subjects, the department also hired emigres from the Soviet Union, such as the rocket scientist Grigori Tokaty. Other staffers of note include Robert Conquest, whose secretary Celia Kirwan collected Orwell's list. Tracy Philipps was also based at the IRD, working to recruit emigres from Eastern Europe. Many IRD agents were former members of Britain's WWII propaganda department, the Political Warfare Executive (PWE), including former Daily Mirror journalist Leslie Sheridan. This high level of PWE veterans within the IRD, coupled with the similarities between how these two propaganda departments operated, has led some historians to describe the department as a "peacetime PWE". Outside of full-time agents, many historians, writers, and academics were either paid directly to publish anti-communist propaganda by the IRD or whose works were bought and distributed by the department using British embassies to both translate and distribute their works across the globe. Some of these authors includeGeorge Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler (, ; ; ; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest, and was educated in Austria, apart from his early school years. In 1931, Koestler j ...

, Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz ( , , ; 30 June 1911 – 14 August 2004) was a Polish Americans, Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. He primarily wrote his poetry in Polish language, Polish. Regarded as one of the great poets of the ...

, Brian Crozier, Richard Crossman, Will Lawther

Sir William Lawther (20 May 1889 – 1 February 1976) was a politician and trade union leader in the United Kingdom.

Born in Choppington, in Northumberland, Lawther was educated at Choppington Colliery School, then became a coal miner. He becam ...

, A. J. P. Taylor, Baron Wyatt of Weeford, Leonard Schapiro, Denis Healey

Denis Winston Healey, Baron Healey (30 August 1917 – 3 October 2015) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974 to 1979 and as Secretary of State for Defence from 1964 to 1970; he remains the lo ...

, Douglas Hyde

Douglas Ross Hyde (; 17 January 1860 – 12 July 1949), known as (), was an Irish academic, linguist, scholar of the Irish language, politician, and diplomat who served as the first president of Ireland from June 1938 to June 1945. He was a l ...

, Margarete Buber, Victor Kravchenko, W.N. Ewer, Victor Feather, and hundreds (possibly thousands) of others. Some authors such as Bertrand Russell were fully aware of the funding for their books, while others such as the philosopher Bryan Magee

Bryan Edgar Magee (; 12 April 1930 – 26 July 2019) was a British philosopher, broadcaster, politician and author, best known for bringing philosophy to a popular audience.

Early life

Born of working-class parents in Hoxton, London, in 1930, ...

were outraged when they found out.

Bertrand Russell

As part of its remit "to collect and summarize reliable information about Soviet and communist misdoings, to disseminate it to friendly journalists, politicians, and trade unionists, and to support, financially and otherwise, anti-communist publications", it subsidised the publication of books by 'Background Books', including three by Bertrand Russell, ''Why Communism Must Fail'', ''What Is Freedom?'', and ''What Is Democracy?'' The IRD bulk-ordered thousands of copies of Russell's books, including his work ''Why Communism Must Fail'', and worked with the United States government to distribute them using embassies as cover. Working closely with theBritish Council

The British Council is a British organisation specialising in international cultural and educational opportunities. It works in over 100 countries: promoting a wider knowledge of the United Kingdom and the English language (and the Welsh lang ...

, the IRD built Russell's reputation as an anti-communist writer, and to use his works to project power overseas.

Arthur Koestler

Koestler enjoyed strong personal relationships with IRD agents from 1949 onwards and was supportive of the department's anti-communist goals. Koestler's relationship with the British government was so strong that he had become a de facto advisor to British propagandists, urging them to create a popular series of anti-communist left-wing literature to rival the success of the Left Book Club. In return for his services to British propaganda, the IRD assisted Koestler by purchasing thousands of copies of his book ''Darkness at Noon

''Darkness at Noon'' (, ) is a novel by Austrian-Hungarian-born novelist Arthur Koestler, first published in 1940. His best known work, it is the tale of Rubashov, an Old Bolshevik who is arrested, imprisoned, and tried for treason against the ...

'' and distributing them throughout Germany.

Propaganda

The IRD created, sponsored, and distributed a wide range of propaganda publications both fiction and non-fiction, in the form of books, magazines, pamphlets, newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, and cartoons. Books which the IRD believed could be used for British propaganda purposes were translated into dozens of languages and then distributed using British embassies. Most IRD material targeted the Soviet Union, but much IRD work also attacked socialist and anti-colonial revolutionaries inCyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Malaya (now Malaysia), Singapore, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, and Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

. In Britain, the department used its propaganda to spread smear stories targeting trade union leaders and human rights activists, but was also used by the Labour Party to conduct internal purges against socialist members.

British introductions to IRD were made discreetly, with journalists being told as little as possible about the department. Propaganda material was sent to their homes under plain cover as correspondence marked "personal" carried no departmental identification or reference. They were told documents were "prepared" in the FCO primarily for members of the diplomatic service, but that it was allowed to give them on a personal basis to a few people outside the service who might find them of interest. As such, they were not statements of official policy and should not be attributed to HMG, nor should the titles themselves be quoted in discussion or in print. The papers should not be shown to anyone else and they were to be destroyed when no longer needed.

''Animal Farm'' - George Orwell

''Animal Farm

''Animal Farm'' (originally ''Animal Farm: A Fairy Story'') is a satirical allegorical novella, in the form of a beast fable, by George Orwell, first published in England on 17 August 1945. It tells the story of a group of anthropomorphic far ...

'' was republished, distributed, translated, and promoted for many years by IRD agents. Of all the propaganda works ever supported by the IRD, ''Animal Farm'' was given more attention and support by IRD agents than any publication in the department's history and arguably given more support from the British and American governments than any other propaganda book in the Cold War. The IRD gained the translation rights to ''Animal Farm'' in Chinese, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Finnish, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Indonesian, Latvian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, and Swedish. The Chinese version of ''Animal Farm'' was created in a joint operation between British and American government propagandists, which also included a pictorial version. To further promote ''Animal Farm'', the IRD commissioned cartoon strips to be planted in newspapers across the globe. The foreign rights to distribute these cartoons were acquired by the IRD for Cyprus, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Nigeria, Trinidad, Jamaica, Fiji, British Guiana and British Honduras.

To further promote ''Animal Farm'', the IRD commissioned cartoon strips to be planted in newspapers across the globe. The foreign rights to distribute these cartoons were acquired by the IRD for Cyprus, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Nigeria, Trinidad, Jamaica, Fiji, British Guiana and British Honduras.

''Encounter'' magazine

In a joint operation with the CIA, '' Encounter'' magazine was established. Published in theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, it was a largely Anglo-American intellectual and cultural journal, originally associated with the anti-Stalinist left

The anti-Stalinist left encompasses various kinds of Left-wing politics, left-wing political movements that oppose Joseph Stalin, Stalinism, neo-Stalinism and the History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), system of governance that Stalin impleme ...

, intended to counter the idea of cold war

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

neutralism. The magazine was rarely critical of American foreign policy, but beyond this editors had considerable publishing freedom. It was edited by Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed U.S. Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry ...

from 1953 to 1966. Spender resigned after it emerged that the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which published the magazine, was being covertly funded by the CIA.

Activities

Italy

In 1948, fearing a victory of theItalian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

in the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

, the IRD instructed the Embassy of the United Kingdom in Rome to disseminate anti-communist propaganda. Ambassador Victor Mallet chaired a small ''ad hoc'' committee to circulate IRD propaganda material to anti-communist journalists and Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

and Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

politicians.

Indonesia

Following the abortive Indonesian Communist coup attempt of 1965 and the subsequent mass killings, the IRD's South East Asia Monitoring Unit in Singapore assisted theIndonesian Army

The Indonesian Army ( (TNI-AD), ) is the army, land branch of the Indonesian National Armed Forces. It has an estimated strength of 300,400 active personnel. The history of the Indonesian Army has its roots in 1945 when the (TKR) "People's Se ...

's destruction of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) by circulating anti-PKI propaganda through several radio channels including the British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public broadcasting, public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved in ...

, Radio Malaysia, Radio Australia, and the Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA or VoA) is an international broadcasting network funded by the federal government of the United States that by law has editorial independence from the government. It is the largest and oldest of the American internation ...

, and through newspapers like ''The Straits Times

''The Straits Times'' (also known informally by its abbreviation ''ST'') is a Singaporean daily English-language newspaper owned by the SPH Media Trust. Established on 15 July 1845, it is the most-widely circulated newspaper in the country and ...

''. The same anti-PKI message was repeated by an anti-Sukarno radio station called Radio Free Indonesia and the IRD's own newsletter. Recurrent themes emphasised by the IRD included the alleged brutality of PKI members in murdering the Indonesian generals and their families, Chinese intervention in the Communist attempt to overthrow the government, and the PKI subverting Indonesian on behalf of foreign powers. The IRD's propaganda efforts were aided by the United States, Australian and Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

n governments which had an interest in supporting the Army's anti-communist mass murder and opposing President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

. The IRD's information efforts helped corroborate the Indonesia Army's propaganda efforts against the PKI. In addition, the Harold Wilson Labour Government and its Australian counterpart gave the Indonesian Army leadership an assurance that British and Commonwealth forces would not step up the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation.

British trade unions

In 1969Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

requested actions that would hinder the careers of two "politically motivated" trade unionists

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

, Jack Jones of the Transport and General Workers Union and Hugh Scanlon of the Amalgamated Engineering Union. This issue was raised in the cabinet and further discussed with Secretary of State for Employment Barbara Castle

Barbara Anne Castle, Baroness Castle of Blackburn, (''née'' Betts; 6 October 1910 – 3 May 2002) was a British Labour Party politician who was a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament from 1945 United Kingdom general elec ...

. A plan for detrimental leaks to the media was placed in the IRD files, and the head of the IRD prepared a briefing paper. Information about how this was effected has not been released under the thirty-year rule under a section of the Public Records Act permitting national security exemptions.

Stokeley Carmichael

In 2022 declassified documents showed that the IRD attacked the U.S. Black Power movement with covert disinformation in the 1960s. Civil rights leader Stokeley Carmichael, who had fled to Africa, was targeted; he was claimed to be a foreigner in Africa who was contemptuous of Africans, rather than a Communist stooge. The IRD created a fake west African organisation called ''The Black Power – Africa's Heritage Group'', which criticised Carmichael as an "unbidden prophet from America" who had abandoned the U.S. Black Power cause, with no place in Africa, who was "weaving a bloody trail of chaos in the name of Pan-Africanism", controlled byKwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

, the independence leader and former president of Ghana deposed by a coup in 1966.

Reuters

In 1969Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide writing in 16 languages. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency ...

agreed to open a reporting service in the Middle East as part of an IRD plan to influence the international media. To protect the reputation of Reuters, which might have been damaged if the funding from the British government became known, the BBC paid Reuters "enhanced subscriptions" for access to its news service and was in turn compensated by the British government for the extra expense. The BBC paid Reuters £350,000 over four years.

Chile

The IRD conducted a propaganda programme to preventSalvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 1970 until Death of Salvador Allende, his death in 1973 Chilean coup d'état, 1973. As a ...

from being elected president of Chile in the 1964 election. Allende's nationalisation policy threatened British and US interests since Chile's copper mines were largely owned by US companies. In the lead up to the election, the IRD was told by a British Cabinet Office unit called the "Counter-subversion Committee's Working Group on Latin America" that "it will be important to prevent significant gains by the extreme left". The IRD supported Allende's opponent Eduardo Frei Montalva

Eduardo Nicanor Frei Montalva (; 16 January 1911 – 22 January 1982) was a Chileans, Chilean political leader. In his long political career, he was Minister of Public Works, president of his Christian Democratic Party (Chile), Christia ...

in the lead up to the election by distributing material to its reliable contacts that was critical of Allende, and favourable to Frei.

The distribution of propaganda material by the IRD diminished after Allende was elected president in 1970, but increased again after the 1973 coup. The material was passed "to the Chilean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government information organisations" and the dictatorship's "military intelligence" services. The IRD helped Pinochet's government to develop a counter-insurgency strategy in order to stabilise it against domestic opposition. The counter insurgency techniques provided to Chile by the IRD were developed by Britain during its colonial interventions in Southeast Asia. The Chilean authorities were told not to reveal that the information came from the British government.

Controversies

The ethical objection raised by IRD's critics was that the public did not know the source of the information and could therefore not make allowances for the possible bias. It differed thus from straightforward propaganda from the British point of view. This was countered by saying that the information was given to those who were already sympathetic to democracy and the West, and who had arrived at these positions independently.Unattributed use by authors

Some writers who worked for the IRD have since been found to have used IRD material and presented it to the academic community as though it were their own work. Robert Conquest's book '' The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties'' "drew heavily from IRD files", and multiple volumes of Soviet history which Conquest edited had also contained IRD material.Orwell's List

The IRD became the subject of heavy controversy in the UK after it was revealed that George Orwell had given the department a list of 38 people he suspected of being secret Communists or " fellow travellers". The existence of Orwell's List, also known as Foreign Office File "FO/111/189", was made public in 1996. The names included on the list were not made public until 2003. The list came into possession of the IRD in 1949, after being collected by IRD agent Celia Kirwan. Kirwan was a close friend of Orwell, she was also Arthur Koestler's sister-in-law and the secretary for fellow IRD agent Robert Conquest. Guy Burgess was based in the next office to her own. The list itself was divided into three columns headed "Name" "Job" and "Remarks", and referred to those listed as "FTs" meaning Fellow Travelers, and labelled people he believed of being suspected of being secret Marxists as "cryptos". Some of the names listed by Orwell included filmmaker

The existence of Orwell's List, also known as Foreign Office File "FO/111/189", was made public in 1996. The names included on the list were not made public until 2003. The list came into possession of the IRD in 1949, after being collected by IRD agent Celia Kirwan. Kirwan was a close friend of Orwell, she was also Arthur Koestler's sister-in-law and the secretary for fellow IRD agent Robert Conquest. Guy Burgess was based in the next office to her own. The list itself was divided into three columns headed "Name" "Job" and "Remarks", and referred to those listed as "FTs" meaning Fellow Travelers, and labelled people he believed of being suspected of being secret Marxists as "cryptos". Some of the names listed by Orwell included filmmaker Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

, writer J. B. Priestley, actor Michael Redgrave, historian E. H. Carr, ''New Statesman

''The New Statesman'' (known from 1931 to 1964 as the ''New Statesman and Nation'') is a British political and cultural news magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first c ...

'' editor Kingsley Martin, ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''s Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty, historian Isaac Deutscher, Labour Party MP Tom Driberg and the novelist Naomi Mitchison

Naomi Mary Margaret Mitchison, Baroness Mitchison (; 1 November 1897 – 11 January 1999) was a List of Scottish novelists, Scottish novelist and poet. Often called a doyenne of Scottish literature, she wrote more than 90 books of historical an ...

, as well as lesser-known writers and journalists. Only one of the people named by Orwell, Peter Smollett, was ever revealed to have been a real Soviet agent. Peter Smollett, who Orwell claimed "...gives strong impression of being some kind of Russian agent. Very slimy person." Smollett had been the head of the Soviet section in the British Ministry of Information, while in fact being a Soviet agent who had been recruited by Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963, he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring that had divulged British secr ...

.

Reactions to Orwell's list have been mixed, with some people crediting Orwell's actions to mental illness, others labelling him a "snitch" and theorising that Orwell's suspicion of numerous African, homosexual, and Jewish people within his list signified bigotry, and others minimising the significance the list. Academic Norman MacKenzie, who knew Orwell personally and considered him a friend, lived long enough to discover that Orwell had reported him to the British secret service on suspicion of being a secret Communist. MacKenzie responded to learning that Orwell had reported him, and credited Orwell's actions to his degrading mental state caused by tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. Alexander Cockburn was far less sympathetic, labelling Orwell a "snitch" and a bigot for the information included in Orwell's notebook, another list of suspected Communists that came into the possession of the IRD. This notebook created by Orwell which contained 135 names, was also found to have been held by the Foreign Office. Within this document, Orwell describes African-American Civil Rights leader Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

as a "very anti-white...U.S Negro".

On the other hand, Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British and American author and journalist. He was the author of Christopher Hitchens bibliography, 18 books on faith, religion, culture, politics, and literature. He was born ...

wrote in 1996 that the list only names people already publicly known as left-leaning. Citing Kirwan's account of the event, Hitchens noted that Orwell "was only giving irwanthe names of various people who were already very well known to anybody who studied Communism. It wasn't as if he was revealing the names of spies." Hitchens further noted, "Nothing that Orwell discussed with his old flame was ever used for a show trial or a bullying "hearing" or a blacklist or a witch-hunt. He wasn't interested in unearthing heresy or in getting people fired or in putting them under the discipline of a loyalty oath. He just wanted to keep a clear accounting in the battle of ideas."

Fabricated rape and paedophilia allegations

During the Cyprus Emergency, IRD agents used newspaper journalists to spread fabricated stories that guerrillas belonging to the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters ( EOKA), had raped schoolgirls. These propaganda stories were manufactured as a part of 'Operation TEA-PARTY', a black propaganda operation in which IRD agents created pamphlets accusing EOKA guerrillas of forcing schoolgirls to have sex with them, and alleging that the youngest of these schoolgirls was 12 years old. Among other fabricated stories, IRD agents attempted to convince American journalists that EOKA had links to Communism in an attempt to gain American support, citing "secret documents" and "classified intelligence reports" which said journalists were never allowed to view.Discovery and closure

The department was said to be closed down by then Foreign Secretary, David Owen, in 1977. Its existence was not made public until 1978.See also

* Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), part of the United States CIA * Research, Information and Communications Unit, part of the UK Home OfficeReferences

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Facsimile of page (PDF)

* * * * * * * * * {{cite journal , last=Wilford , first=Hugh , date=1998 , title=The Information Research Department: Britain's Secret Cold War Weapon Revealed , url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097531 , journal=Review of International Studies , volume=24 , issue=3 , pages=353–369 , doi=10.1017/S0260210598003532 , jstor=20097531, s2cid=145286473 , via=JSTORE , url-access=subscription Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Cold War propaganda Government agencies established in 1948 1977 disestablishments in the United Kingdom British propaganda organisations Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations 1948 establishments in the United Kingdom George Orwell Anti-communist propaganda Anti-communist organizations in the United Kingdom News agencies based in the United Kingdom Defunct United Kingdom intelligence agencies