Indian inventions on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This list of Indian inventions and discoveries details the inventions, scientific discoveries and contributions of India, including the ancient, classical and post-classical nations in the subcontinent historically referred to as India and the modern Indian state. It draws from the whole

Antentop

', Vol.2, No.3, p.87-96, Belgorod, Russia *

* BharatNet(National Optical Fibre Network) is establishment, management, and operation of the National Optical Fibre Network as an Infrastructure to provide a minimum of 100 Mbit/s broadband connectivity to all rural and remote areas. BBNL was established in 2012 to lay the optical fiber.

*

* BharatNet(National Optical Fibre Network) is establishment, management, and operation of the National Optical Fibre Network as an Infrastructure to provide a minimum of 100 Mbit/s broadband connectivity to all rural and remote areas. BBNL was established in 2012 to lay the optical fiber.

*

''Pachisi''

The earliest evidence of this game in India is the depiction of boards on the caves of Ajanta. A variant of this game, called Ludo, made its way to England during the British Raj. *

* 2G-Ethanol technology, which produces ethanol from agricultural residue feedstock, has the potential to significantly reduce emissions from the transportation and agricultural sectors in India.The IP belongs to Praj Industries.

* High ash coal gasification(Coal to Methanol), The Central Government gave the country world's first 'coal to methanol' (CTM) plant built by the Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL). The plant was inaugurated in BHEL's Hyderabad unit, The pilot project is the first that uses the gasification method for converting high-ash coal into methanol. Handling of high ash and heat required to melt this high amount of ash is a challenge in the case of Indian coal, which generally has high ash content. Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited has developed the fluidized bed gasification technology suitable for high ash Indian coals to produce syngas and then convert syngas to methanol with 99% purity.

* CBM in Blast Furnace, Tata Steel has initiated the trial for continuous injection of Coal Bed Methane (CBM) gas in one of the Blast Furnaces at its Jamshedpur Works, making it the first such instance in the world where a steel company has used CBM as injectant. This process is expected to reduce coke rate by 10 kg/thm, which will be equivalent to reducing 33 kg of per tonne of crude steel.

*

* 2G-Ethanol technology, which produces ethanol from agricultural residue feedstock, has the potential to significantly reduce emissions from the transportation and agricultural sectors in India.The IP belongs to Praj Industries.

* High ash coal gasification(Coal to Methanol), The Central Government gave the country world's first 'coal to methanol' (CTM) plant built by the Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL). The plant was inaugurated in BHEL's Hyderabad unit, The pilot project is the first that uses the gasification method for converting high-ash coal into methanol. Handling of high ash and heat required to melt this high amount of ash is a challenge in the case of Indian coal, which generally has high ash content. Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited has developed the fluidized bed gasification technology suitable for high ash Indian coals to produce syngas and then convert syngas to methanol with 99% purity.

* CBM in Blast Furnace, Tata Steel has initiated the trial for continuous injection of Coal Bed Methane (CBM) gas in one of the Blast Furnaces at its Jamshedpur Works, making it the first such instance in the world where a steel company has used CBM as injectant. This process is expected to reduce coke rate by 10 kg/thm, which will be equivalent to reducing 33 kg of per tonne of crude steel.

*

cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.T ...

and technological history of India, during which architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

, metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, metrology

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to standardise units in Fran ...

and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

were among the branches of study pursued by its scholars. During recent times science and technology in the Republic of India

After independence, Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, initiated reforms to promote higher education and science and technology in India. The Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)—conceived by a 22-member committee of scho ...

has also focused on automobile engineering

Automotive engineering, along with aerospace engineering and naval architecture, is a branch of vehicle engineering, incorporating elements of mechanical, electrical, electronic, software, and safety engineering as applied to the design, manufac ...

, information technology

Information technology (IT) is the use of computers to create, process, store, retrieve, and exchange all kinds of data . and information. IT forms part of information and communications technology (ICT). An information technology syste ...

, communications

Communication (from la, communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with") is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inquir ...

as well as research into space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consi ...

and polar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

Polar may refer to:

* Geographical pole, either of two fixed points on the surface of a rotating body or planet, at 90 degrees from the equator, based on the axis around which a body rotates

*Polar climate, the cli ...

technology.

For the purpose of this list, the invention

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

s are regarded as technological firsts developed in India, and as such does not include foreign technologies which India acquired through contact. It also does not include technologies or discoveries developed elsewhere and later invented separately in India, nor inventions by Indian emigres in other places. Changes in minor concepts of design or style and artistic innovations do not appear in the lists.

Inventions

Administration

*Janapada

The Janapadas () (c. 1500–600 BCE) were the realms, republics (ganapada) and kingdoms (saamarajya) of the Vedic period on the Indian subcontinent. The Vedic period reaches from the late Bronze Age into the Iron Age: from about 1500 BCE to ...

(democratic republic system) (1100-500 BCE)

* Local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loc ...

: presence of municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the ...

in Indus Valley Civilization is characterised by rubbish bins and drainage system throughout urban areas. Megasthenes also mentions presence of a local government in the Mauryan city of Pataliputra

Pataliputra (IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at t ...

.

* Passport

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that contains a person's identity. A person with a passport can travel to and from foreign countries more easily and access consular assistance. A passport certifies the personal ...

: Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

() make mentions of passes issued at the rate of one '' masha'' per pass to enter and exit the country. Chapter 34 of the Second Book of Arthashastra concerns with the duties of the () who must issue sealed passes before a person could enter or leave the countryside. This constitutes first passports and passbooks in world history

Communication

*Crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers that consists of a piece of crystalline mineral which rectifies the alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector (dem ...

by Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contribution ...

. Crystals were first used as radio wave detectors in 1894 by Bose in his microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

experiments. Bose first patented a crystal detector in 1901.

* Horn antenna

A horn antenna or microwave horn is an antenna that consists of a flaring metal waveguide shaped like a horn to direct radio waves in a beam. Horns are widely used as antennas at UHF and microwave frequencies, above 300 MHz. They are ...

or microwave horn, One of the first horn antennas was constructed by Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contribution ...

in 1897. reprinted in Igor Grigorov, Ed., Antentop

', Vol.2, No.3, p.87-96, Belgorod, Russia *

Microwave Communication

Microwave transmission is the transmission of information by electromagnetic waves with wavelengths in the microwave frequency range of 300MHz to 300GHz(1 m - 1 mm wavelength) of the electromagnetic spectrum. Microwave signals are normally limi ...

: The first public demonstration of microwave transmission was made by Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contribution ...

, in Calcutta, in 1895, two years before a similar demonstration by Marconi in England, and just a year after Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge, (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was a British physicist and writer involved in the development of, and holder of key patents for, radio. He identified electromagnetic radiation independent of Hertz's proof and at his ...

's commemorative lecture on Radio communication, following Hertz's death. Bose's revolutionary demonstration forms the foundation of the technology used in mobile telephony, radars, satellite communication, radios, television broadcast, WiFi, remote controls and countless other applications.

Computers and programming languages

*J Sharp

Visual J# (pronounced "jay-sharp") is a discontinued implementation of the J# programming language that was a transitional language for programmers of Java and Visual J++ languages, so they could use their existing knowledge and applications wi ...

: Visual J# programming language

A programming language is a system of notation for writing computer programs. Most programming languages are text-based formal languages, but they may also be graphical. They are a kind of computer language.

The description of a programming ...

was a transitional language for programmers of Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

and Visual J++

Visual J++ is Microsoft's discontinued implementation of Java. Syntax, keywords, and grammatical conventions were the same as Java's. It was introduced in 1996 and discontinued in January 2004, replaced to a certain extent by J# and C#.

The i ...

languages, so they could use their existing knowledge and applications on .NET Framework

The .NET Framework (pronounced as "''dot net"'') is a proprietary software framework developed by Microsoft that runs primarily on Microsoft Windows. It was the predominant implementation of the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) until bein ...

. It was developed by the Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern Indi ...

-based Microsoft India Development Center at HITEC City in India.

*Julia

Julia is usually a feminine given name. It is a Latinate feminine form of the name Julio and Julius. (For further details on etymology, see the Wiktionary entry "Julius".) The given name ''Julia'' had been in use throughout Late Antiquity (e.g ...

is a high-level, dynamic programming language. Its features are well suited for numerical analysis and computational science. Viral B. Shah

Viral B Shah ( hi, वीराल बी. शाह, link=no) is an Indian computer scientist, best known for being a co-creator of the Julia programming language. He was also actively involved in the initial design of the Aadhaar project in Ind ...

an Indian computer scientist contributed to the development of the language in Bangalore while also actively involved in the initial design of the Aadhaar project in India using India Stack

India Stack refers to the ambitious project of creating a unified software platform to bring India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh- ...

.

* Kojo: Kojo is a programming language

A programming language is a system of notation for writing computer programs. Most programming languages are text-based formal languages, but they may also be graphical. They are a kind of computer language.

The description of a programming ...

and integrated development environment

An integrated development environment (IDE) is a software application that provides comprehensive facilities to computer programmers for software development. An IDE normally consists of at least a source code editor, build automation tools ...

(IDE) for computer programming and learning. Kojo is an open-source software

Open-source software (OSS) is computer software that is released under a license in which the copyright holder grants users the rights to use, study, change, and distribute the software and its source code to anyone and for any purpose. ...

. It was created, and is actively developed, by Lalit Pant, a computer programmer and teacher living in Dehradun

Dehradun () is the capital and the List of cities in Uttarakhand by population, most populous city of the Indian state of Uttarakhand. It is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous Dehradun district, district and is governed by the Dehr ...

, India.

* RISC-V

RISC-V (pronounced "risk-five" where five refers to the number of generations of RISC architecture that were developed at the University of California, Berkeley since 1981) is an open standard instruction set architecture (ISA) based on est ...

ISA (microprocessor) implementations:

** SHAKTI

In Hinduism, especially Shaktism (a theological tradition of Hinduism), Shakti (Devanagari: शक्ति, IAST: Śakti; lit. "Energy, ability, strength, effort, power, capability") is the primordial cosmic energy, female in aspect, and r ...

- Open Source, Bluespec System Verilog

Verilog, standardized as IEEE 1364, is a hardware description language (HDL) used to model electronic systems. It is most commonly used in the design and verification of digital circuits at the register-transfer level of abstraction. It is als ...

definitions, for FinFET implementations of the ISA, have been created at IIT Madras

Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT Madras) is a public technical university located in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. As one of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), it is recognized as an Institute of National Importance and has b ...

, and are hosted on GitLab

GitLab Inc. is an open-core company that operates GitLab, a DevOps software package which can develop, secure, and operate software. The open source software project was created by Ukrainian developer Dmitriy Zaporozhets and Dutch developer ...

.

** VEGA Microprocessors

VEGA Microprocessors are a portfolio of indigenous processors developed by C-DAC. The portfolio includes several 32-bit/64-bit Single/Multi-core Superscalar In-order/Out-of-Order high performance processors based on the RISC-V ISA. Also featur ...

: India's first indigenous 64-bit, superscalar, out-of-order, multi-core RISC-V Processor design, developed by C-DAC.

Construction, civil engineering and architecture

* BharatNet(National Optical Fibre Network) is establishment, management, and operation of the National Optical Fibre Network as an Infrastructure to provide a minimum of 100 Mbit/s broadband connectivity to all rural and remote areas. BBNL was established in 2012 to lay the optical fiber.

*

* BharatNet(National Optical Fibre Network) is establishment, management, and operation of the National Optical Fibre Network as an Infrastructure to provide a minimum of 100 Mbit/s broadband connectivity to all rural and remote areas. BBNL was established in 2012 to lay the optical fiber.

*English Bond

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called ''courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by siz ...

: The English bond is a form of brickwork with alternating stretching and heading courses

Course may refer to:

Directions or navigation

* Course (navigation), the path of travel

* Course (orienteering), a series of control points visited by orienteers during a competition, marked with red/white flags in the terrain, and corresponding ...

, with the headers centred over the midpoint of the stretchers, and perpends in each alternate course aligned. Harappan architecture

Harappan architecture is the architecture of the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization, an ancient society of people who lived during circa 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE in the Indus Valley of modern-day Pakistan and India.

The civilization's cities were ...

in South Asia was the first to use the so-called English bond in building with bricks.

* Dedicated Freight Corridors is an electric high speed and high capacity railway corridor that is exclusively meant for the transportation of double stack freight cargo.It will help in freeing up the passenger corridor.

*Dockyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

: The world's earliest enclosed dockyard was built in the Harappan port city of Lothal circa 2600 BC in Gujarat, India. *Genome Valley

Genome Valley is an Indian high-technology business district spread across /(3.1 sq mi) in Hyderabad, India. It is located across the suburbs, Turakapally, Shamirpet, Medchal, Uppal, Patancheru, Jeedimetla, Gachibowli and Keesara. The Geno ...

is world's first organized cluster for Life Sciences R&D and Clean Manufacturing activities, with world-class infrastructure facilities in the form of Industrial / Knowledge Parks, Special Economic Zones (SEZs), Multi-tenanted dry and wet laboratories and incubation facilities.

* Light Gauge Steel framing is a construction technology using cold-formed steel as the construction material. It can be used for roof systems, floor systems, wall systems, roof panels, decks, or the entire buildings.

* Multi-Modal Logistics Parks (MMLPs) defined as a freight-handling facility with a minimum area of 100 acres (40.5 hectares), with various modes of transport access, mechanized warehouses, specialized storage solutions such as cold storage, facilities for mechanized material handling and inter-modal transfer container terminals, and bulk and break-bulk cargo terminals.

* Plumbing

Plumbing is any system that conveys fluids for a wide range of applications. Plumbing uses pipes, valves, plumbing fixtures, tanks, and other apparatuses to convey fluids. Heating and cooling (HVAC), waste removal, and potable water delive ...

: Standardized earthen plumbing pipes with broad flanges making use of asphalt

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term ...

for preventing leakages appeared in the urban settlements of the Indus Valley Civilization by 2700 BC. Earthen pipes were used in the Indus Valley c. 2700 BC for a city-scale urban drainage system,

* Plastic road are made entirely of plastic or of composites of plastic with other materials. Plastic roads are different from standard roads in the respect that standard roads are made from asphalt concrete, which consists of mineral aggregates and asphalt. Most plastic roads sequester plastic waste within the asphalt as an aggregate. Plastic roads first developed by Rajagopalan Vasudevan in 2001

* Chenab Bridge

The Chenab Rail Bridge is a steel and concrete arch bridge between Bakkal and Kauri and just 42 km from main Reasi town in the Reasi district of Jammu and Kashmir, India. The bridge spans the Chenab River at a height of above the river, mak ...

is world's highest rail bridge and world's first blast-proof steel bridge.The bridge is built using 63mm-thick special blast-proof steel.

* Squat toilet: Toilet platforms above drains, in the proximity of wells, are found in several houses of the cities of Mohenjodaro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a ...

from the 3rd millennium BCE.

* Soil Health Card under the scheme, the government plans to issue soil cards to farmers which will carry crop-wise recommendations of nutrients and fertilisers required for the individual farms to help farmers to improve productivity through judicious use of inputs. All soil samples are to be tested in various soil test

Soil test may refer to one or more of a wide variety of soil analysis conducted for one of several possible reasons. Possibly the most widely conducted soil tests are those done to estimate the plant-available concentrations of plant nutrients, i ...

ing labs across the country.

* Stepwell

Stepwells (also known as vavs or baori) are wells or ponds with a long corridor of steps that descend to the water level. Stepwells played a significant role in defining subterranean architecture in western India from 7th to 19th century. So ...

: Earliest clear evidence of the origins of the stepwell is found in the Indus Valley Civilisation's archaeological site at Mohenjodaro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Dholavira

Dholavira ( gu, ધોળાવીરા) is an archaeological site at Khadirbet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch District, in the state of Gujarat in western India, which has taken its name from a modern-day village south of it. This village is ...

in India. The three features of stepwells in the subcontinent are evident from one particular site, abandoned by 2500 BCE, which combines a bathing pool, steps leading down to water, and figures of some religious importance into one structure. The early centuries immediately before the common era saw the Buddhists and the Jains of India adapt the stepwells into their architecture. Both the wells and the form of ritual bathing reached other parts of the world with Buddhism. Rock-cut step wells in the subcontinent date from 200 to 400 CE. Subsequently, the wells at Dhank (550625 CE) and stepped ponds at Bhinmal

Bhinmal (previously Shrimal Nagar) is an ancient town in the Jalore District of Rajasthan, India. It is south of Jalore. Bhinmal was the capital of the Bhil king, then the capital of Gurjaradesa, comprising modern-day southern Rajasthan and n ...

(850950 CE) were constructed.Livingston & Beach, page xxiii

* Stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circum ...

: The origin of the stupa can be traced to 3rd-century BCE India.Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). ''Pagoda''. It was used as a commemorative monument associated with storing sacred relics. The stupa architecture was adopted in Southeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

and East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

, where it evolved into the pagoda

A pagoda is an Asian tiered tower with multiple eaves common to Nepal, India, China, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia. Most pagodas were built to have a religious function, most often Buddhist but sometimes Taoist, ...

, a Buddhist monument used for enshrining sacred relics.

Finance and banking

*Cheque

A cheque, or check (American English; see spelling differences) is a document that orders a bank (or credit union) to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The pers ...

: There is early evidence of using cheques. In India, during the Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until ...

(from 321 to 185 BC), a commercial instrument called the adesha was in use, which was an order on a banker desiring him to pay the money of the note to a third person.

* Direct Benefit Transfer, This program aims to transfer subsidies directly to the people through their bank accounts. It is hoped that crediting subsidies into bank accounts will reduce leakages, delays, etc.

* Digital Banking Unit(DBU) is a specialised fixed point business unit/hub housing certain minimum digital infrastructure for delivering digital banking products and services as well as servicing existing financial products & services digitally, in both self-service and assisted mode.

* Payments bank

Payments banks are new model of banks, conceptualised by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which cannot issue credit. These banks can accept a restricted deposit, which is currently limited to ₹200,000 per customer and may be increased further. ...

is an Indian new model of banks conceptualised by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) without issuing credit.

* Small Finance Bank are a type of niche banks in India. Banks with a small finance bank (SFB) license can provide basic banking service of acceptance of deposits and lending. The aim behind these is to provide financial inclusion to sections of the economy not being served by other banks,

* Micro Finance Institutions(MFI) is an organization that offers financial services to low income populations.

Games

*Badminton

Badminton is a racquet sport played using racquets to hit a shuttlecock across a net. Although it may be played with larger teams, the most common forms of the game are "singles" (with one player per side) and "doubles" (with two players p ...

: The game may have originally developed among expatriate officers in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

*Blindfold Chess

Blindfold chess, also known as ''sans voir'', is a form of chess play wherein the players do not see the positions of the pieces and do not touch them. This forces players to maintain a mental model of the positions of the pieces. Moves are commu ...

: Games prohibited by Buddha includes a variant of ashtapada game played on imaginary boards. ''Akasam astapadam'' was an ''ashtapada'' variant played with no board, literally "astapadam played in the sky". A correspondent in the American Chess Bulletin identifies this as likely the earliest literary mention of a blindfold chess variant.

*Carrom

Carrom is a tabletop game of Indian origin in which players flick discs, attempting to knock them to the corners of the board. The game is very popular in the Indian subcontinent, and is known by various names in different languages. In Sou ...

: The game of carrom originated in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

. One carrom board with its surface made of glass is still available in one of the palaces in Patiala, India. It became very popular among the masses after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. State-level competitions were being held in the different states of India during the early part of the twentieth century. Serious carrom tournaments may have begun in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

in 1935 but by 1958, both India and Sri Lanka had formed official federations of carrom clubs, sponsoring tournaments and awarding prizes.

* Chaturanga

Chaturanga ( sa, चतुरङ्ग; ') is an ancient Indian strategy game. While there is some uncertainty, the prevailing view among chess historians is that it is the common ancestor of the board games chess (European), xiangqi (Chines ...

: The precursor of chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

originated in India during the Gupta dynasty

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed from the early 4th century CE to late 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period is considered as the Gold ...

(c. 280550 CE).Murray (1913)Forbes (1860)Jones, William (1807). "On the Indian Game of Chess". pages 323333Linde, Antonius (1981) Both the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian. ...

and Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

s ascribe the origins of the game of Chess to the Indians.Wilkinson, Charles K (May 1943)Bird (1893), page 63 The words for "chess" in Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as ( ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

are ''chatrang'' and ''shatranj

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as i ...

'' respectively – terms derived from '' caturaṅga'' in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

,Hooper & Whyld (1992), page 74Sapra, Rahul (2000). "Sports in India". Students' Britannica India (Vol. 6). Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. p. 106. . which literally means an ''army of four divisions'' or ''four corps''.Meri (2005), page 148Basham (2001), page 208 Chess spread throughout the world and many variants of the game soon began taking shape.Encyclopædia Britannica (2002). ''Chess: Ancient precursors and related games''. This game was introduced to the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

from India and became a part of the princely or courtly education of Persian nobility. Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

pilgrims, Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

traders and others carried it to the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The t ...

where it was transformed and assimilated into a game often played on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares. Chaturanga reached Europe through Persia, the Byzantine empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the expanding Arabian

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

empire.Encyclopædia Britannica (2007). ''Chess: Introduction to Europe''. Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

carried Shatranj to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and Spain by the 10th century where it took its final modern form of chess.

* Kabaddi

Kabaddi is a contact team sport. Played between two teams of seven players, the objective of the game is for a single player on offence, referred to as a "raider", to run into the opposing team's half of the court, touch out as many of their ...

: The game of ''kabaddi'' originated in India during prehistory.Alter, page 88 Suggestions on how it evolved into the modern form range from wrestling exercises, military drills, and collective self-defence but most authorities agree that the game existed in some form or the other in India during the period between 1500 and 400 BCE.

*Kalaripayattu

Kalaripayattu (; also known simply as Kalari) is an Indian martial art that originated in modern-day Kerala, a state on the southwestern coast of India. Kalaripayattu is known for its long-standing history within Indian martial arts, and i ...

: One of the world's oldest form of martial arts is Kalaripayattu

Kalaripayattu (; also known simply as Kalari) is an Indian martial art that originated in modern-day Kerala, a state on the southwestern coast of India. Kalaripayattu is known for its long-standing history within Indian martial arts, and i ...

that developed in the southwest state of Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South Ca ...

in India. It is believed to be the oldest surviving martial art in India, with a history spanning over 3,000 years.

* Ludo: Pachisi

Pachisi (, Hindustani: əˈtʃiːsiː is a cross and circle board game that originated in Ancient India. It is described in the ancient text ''Mahabharata'' under the name of "Pasha". It is played on a board shaped like a symmetrical cross. A ...

originated in India by the 6th century.MSN Encarta (2008)''Pachisi''

The earliest evidence of this game in India is the depiction of boards on the caves of Ajanta. A variant of this game, called Ludo, made its way to England during the British Raj. *

Mallakhamba

Mallakhamba or mallakhamb is a traditional sport, originating from the Indian subcontinent, in which a gymnast performs aerial yoga or gymnastic postures and wrestling grips in concert with a vertical stationary or hanging wooden pole, cane, o ...

: It is a traditional sport, originating from the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

, in which a gymnast

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, sh ...

performs aerial yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciou ...

or gymnastic

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, sh ...

postures and wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat s ...

grips in concert with a vertical stationary or hanging wooden pole, cane, or rope.The earliest literary known mention of Mallakhamb is in the 1135 CE Sanskrit classic '' Manasollasa'', written by Someshvara III

Someshvara III (; ) was a Western Chalukya king (also known as the Kalyani Chalukyas), the son and successor of Vikramaditya VI. He ascended the throne of the Western Chalukya Kingdom in 1126 CE, or 1127 CE.

Someshvara III, the third king in t ...

. It has been thought to be the ancestor of Pole Dancing

Pole dance combines dance and acrobatics centered on a vertical pole. This performance art form takes place not only in gentleman's clubs as erotic dance, but also as a mainstream form of fitness, practiced in gyms and dedicated dance studios ...

.

* Nuntaa, also known as Kutkute.

* Seven Stones: An Indian subcontinent game also called Pitthu is played in rural areas has its origins in the Indus Valley Civilization.

* Snakes and ladders: Vaikunta pali Snakes and ladders originated in India as a game based on morality.Augustyn, pages 2728 During British rule of India, this game made its way to England, and was eventually introduced in the United States of America by game-pioneer Milton Bradley

Milton Bradley (November 8, 1836 – May 30, 1911) was an American business magnate, game pioneer and publisher, credited by many with launching the board game industry, with his eponymous enterprise, which was purchased by Hasbro in 1984, and ...

in 1943.

* Suits game: Kridapatram is an early suits game, made of painted rags, invented in Ancient India. The term ''kridapatram'' literally means "painted rags for playing." Paper playing cards first appeared in East Asia during the 9th century. The medieval Indian game of ''ganjifa

Ganjifa, Ganjapa or Gânjaphâ, is a card game and type of playing cards that are most associated with Persia and India. After Ganjifa cards fell out of use in Iran before the twentieth century, India became the last country to produce them. The f ...

'', or playing cards, is first recorded in the 16th century.

* Table Tennis

Table tennis, also known as ping-pong and whiff-whaff, is a sport in which two or four players hit a lightweight ball, also known as the ping-pong ball, back and forth across a table using small solid rackets. It takes place on a hard table div ...

: It has been suggested that makeshift versions of the game were developed by British military officers in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

around the 1860s or 1870s, who brought it back with them.

* Vajra-mushti: refers to a wrestling where knuckleduster like weapon is employed.The first literary mention of vajra-musti comes from the ''Manasollasa'' of the Chalukya

The Chalukya dynasty () was a Classical Indian dynasty that ruled large parts of southern and central India between the 6th and the 12th centuries. During this period, they ruled as three related yet individual dynasties. The earliest dynast ...

king Someswara III (1124–1138), although it has been conjectured to have existed since as early as the Maurya dynasty

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

Genetics

*Amrapali

Āmrapālī, also known as "Ambapālika", "Ambapali", or "Amra" was a celebrated '' nagarvadhu'' (royal courtesan) of the republic of Vaishali (located in present-day Bihar) in ancient India around 500 BC. Following the Buddha's teachings, she ...

mango is a named mango cultivar introduced in 1971 by Dr. Pijush Kanti Majumdar at the Indian Agriculture Research Institute in Delhi.

* Synthetic genes and decoding of protein synthesising gene: Indian-American biochemist Har Gobind Khorona, created the first synthetic gene and uncovered how a DNA's genetic code determines protein synthesis – which dictates how a cell functions. That discovery earned Khorana, along with his two colleagues, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1968.

*''Pseudomonas putida

''Pseudomonas putida'' is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, saprotrophic soil bacterium.

Based on 16S rRNA analysis, ''P. putida'' was taxonomically confirmed to be a ''Pseudomonas'' species (''sensu stricto'') and placed, along with several other ...

'': Indian (Bengali) inventor and microbiologist Ananda Mohan Chakrabarty created a variety of man-made microorganism to break down crude oil. He genetically engineered a new variety of ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative, Gammaproteobacteria, belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae and containing 191 described species. The members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able t ...

'' bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

("the oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

-eating bacteria") in 1971. In ''Diamond v. Chakrabarty

''Diamond v. Chakrabarty'', 447 U.S. 303 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court case dealing with whether living organisms can be patented. Writing for a five-justice majority, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger held that human-made bacteria could ...

'', the United States Supreme Court granted Chakrabarty's invention patent, even though it was a living organism. The court ruling decreed that Chakrabarty's discovery was "not nature's handiwork, but his own..." Chakrabarty secured his patent in 1980.

* Mynvax is world's first "warm" COVID-19 vaccine, developed by IISc

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in science, engineering, design, and management. It is located in Bengaluru, in the Indian state of Karnataka. The institute was ...

, capable of withstanding 37C for a month and neutralise all coronavirus variants of concern.

* ZyCoV-D

ZyCoV-D is a DNA plasmid-based COVID-19 vaccine developed by Indian pharmaceutical company Cadila Healthcare, with support from the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council. It is approved for emergency use in India.

Technolo ...

vaccine, World's First DNA Based Covid-19 Vaccine.

Metallurgy and manufacturing

Crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

: Perhaps as early as 300 BCE—although certainly by 200 BCE—high quality steel was being produced in southern India, by what Europeans would later call the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon.

* Diamond drills: in the 12th century BCE or 7th century BCE, Indians not only innovated use of diamond tipped drills but also invented double diamond tipped drills for bead manufacturing.

* Diamond cutting and polishing: The technology of cutting and polishing diamonds was invented in India, Ratnapariksha, a text dated to 6th century talks about diamond cutting and Al-Beruni speaks about the method of using lead plate for diamond polishing in the 11th century CE.

* DMR grade steels for several high-technology applications, such as military hardware and aerospace, need to possess ultrahigh strength (UHS; minimum yield strength of 1380 MPa (200 ksi)) coupled with high fracture toughness in order to meet the requirement of minimum weight while ensuring high reliability.

* Etched Carnelian beads: are a type of ancient decorative beads made from carnelian

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semi-precious gemstone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker (the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often used ...

with an etched design in white. They were made according to a technique of alkaline-etching developed by the Harappans during the 3rd millennium BCE and were widely disperced from China in the east to Greece in the west.

* Fortified Cabin, is a car designing technique by TATA Motors such that the high-strength steel structure absorbs impact energy and protects the passenger during an unfortunate collision.Tata Nexon has the fortified cabin design for achieving full 5 star safety ratings.

* Glass blowing: Rudimentary form of glass blowing from Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

is attested earlier than Western Asian counterparts(where it is attested not earlier than 1st century BCE) in the form of Indo-Pacific beads which uses glass blowing to make cavity before being subjected to tube drawn technique for bead making dated more than 2500 BP. Beads are made by attaching molten glass gather to the end of a blowpipe, a bubble is then blown into the gather. The glass blown vessels were rarely attested and were imported commodity in 1st millennium CE though.

* Iron pillar of Delhi: The world's first iron pillar was the Iron pillar of Delhi—erected at the time of Chandragupta II

Chandragupta II (r.c. 376-415), also known by his title Vikramaditya, as well as Chandragupta Vikramaditya, was the third ruler of the Gupta Empire in India, and was one of the most powerful emperors of the Gupta dynasty.

Chandragupta continue ...

Vikramaditya (375413). The pillar has attracted attention of archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes ...

and materials scientists and has been called "a testament to the skill of ancient Indian blacksmiths" because of its high resistance to corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engi ...

.

* Lost-wax casting

Lost-wax casting (also called "investment casting", "precision casting", or ''cire perdue'' which has been adopted into English from the French, ) is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass, or bronze) is ...

: Metal casting by the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900& ...

began around 3500 BC in the Mohenjodaro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';dancing girl" that dates back nearly 5,000 years to the Harappan period (c. 3300–1300 BC). Other examples include the buffalo, bull and dog found at Mohenjodaro and

Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a ...

,Kenoyer, J. M. & H. M.-L. Miller, (1999). Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India., in ''The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World''., ed. V. C. Pigott. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum. two copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

figures found at the Harappan site Lothal

Lothal () was one of the southernmost sites of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation, located in the Bhāl region of the modern state of Gujarāt. Construction of the city is believed to have begun around 2200 BCE.

Archaeological Survey of ...

in the district of Ahmedabad of Gujarat, and likely a covered cart with wheels missing and a complete cart with a driver found at Chanhudaro

Chanhu-daro is an archaeological site belonging to the Indus Valley civilization. The site is located south of Mohenjo-daro, in Sindh, Pakistan. The settlement was inhabited between 4000 and 1700 BCE, and is considered to have been a cen ...

.

* Lost wax

Lost-wax casting (also called "investment casting", "precision casting", or ''cire perdue'' which has been adopted into English from the French, ) is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass, or bronze) is ...

Casting: It is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass or bronze) is cast from an original sculpture. Intricate works can be achieved by this method.The oldest known example of this technique is a 6,000-year old amulet from the Indus Valley Civilization. * Seamless celestial globe

Celestial globes show the apparent positions of the stars in the sky. They omit the Sun, Moon, and planets because the positions of these bodies vary relative to those of the stars, but the ecliptic, along which the Sun moves, is indicated.

...

: Considered one of the most remarkable feats in metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

, it was invented in India in between 1589 and 1590 CE.Kamarustafa (1992), page 48 Before they were rediscovered in the 1980s, it was believed by modern metallurgists to be technically impossible to produce metal globes without any seams

Seam may refer to:

Science and technology

* Seam (geology), a stratum of coal or mineral that is economically viable; a bed or a distinct layer of vein of rock in other layers of rock

* Seam (metallurgy), a metalworking process the joins the end ...

, even with modern technology.

* HIsarna a new process for production of steel, one it says "results in enormous efficiency gains" and reduces energy use and carbon dioxide emissions by a fifth of that in the conventional blast furnace route.It's IP belongs to TATA Steel.

* Spray-drying Buffalo milk, The collective consensus of dairy experts worldwide was that buffalo milk could not be spray-dried due to its high fat content. Harichand Megha Dalaya & his invention of the spray dry equipment, led to the world's first buffalo milk spray-dryer, at Amul Dairy in Gujarat.

*Stoneware

Stoneware is a rather broad term for pottery or other ceramics fired at a relatively high temperature. A modern technical definition is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic made primarily from stoneware clay or non-refractory fire clay. Whether vi ...

: Earliest stonewares, predecessors of porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

have been recorded at Indus Valley Civilization sites of Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a ...

and Mohenjo Daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Tube drawn technology: Indians used tube drawn technology for glass bead manufacturing which was first developed in the 2nd century BCE.

* Tumble polishing: Indians innvoted polishing method in the 10th century BCE for mass production of polished stone beads.

*

*

*

*

*  *

*

''From Milo to Milo: A History of Barbells, Dumbells, and Indian Clubs''

Accessed in September 2008. Hosted on the LA84 Foundation Sports Library. During the

*

*

''PRIMES is in P''

Crandall & Pomerance (2005), pages 200201 Commenting on the impact of this discovery,

Trigonometric functions

.

* Ancient Dentistry: The

* Ancient Dentistry: The

''The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 19011951''

/ref> Brahmachari's cure for Visceral leishmaniasis was the urea salt of para-amino-phenyl stibnic acid which he called Urea Stibamine.

Vigyan Prasar: Government of India Following the discovery of Urea Stibamine, Visceral leishmaniasis was largely eradicated from the world, except for some underdeveloped regions. *

''Diamond''Archived

1 November 2009. The ''

*Early concept of

*Early concept of

. Vigyan Prasar: Government of India. *

''Planck's Law and the Light Quantum Hypothesis''

seeking Einstein's influence to get it published after it was rejected by the prestigious journal ''

(November 2004), Science Popularisation and Public Outreach Committee,

, Viyan Prasar, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. The discovery contributed as a base for significant future research in the field of chemistry. *

Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry

. ''Nature''. Volume 440. 6 April 2006. * Craddock, P.T. et al. (1983). ''Zinc production in medieval India'', World Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 2, Industrial Archaeology. * Crandall, R. & Papadopoulos, J. (18 March 2003).

On the Implementation of AKS-Class Primality Tests

* Crandall, Richard E. & Pomerance, Carl (2005). ''Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective'' (second edition). New York: Springer. . * * * Daryaee, Touraj (2006) in "Backgammon" in ''Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia'' ed. Meri, Josef W. & Bacharach, Jere L, pp. 8889. Taylor & Francis. * Dauxois, Thierry & Peyrard, Michel (2006). ''Physics of Solitons''. England: Cambridge University Press. . * Davreu, Robert (1978). "Cities of Mystery: The Lost Empire of the Indus Valley". ''The World's Last Mysteries''. (second edition). Sydney: Reader's Digest. * Dickinson, Joan Y. (2001). ''The Book of Diamonds''. Dover Publications. . * Drewes, F. (2006). ''Grammatical Picture Generation: A Tree-based Approach''. New York: Springer. * Durant, Will (1935). ''Our Oriental Heritage''. New York: Simon and Schuster. * Dutfield, Graham (2003). ''Intellectual Property Rights and the Life Science Industries: A Twentieth Century History''. Ashgate Publishing. . * Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007)

''History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence''

National Informatics Centre (Government of India). * ''Encyclopedia of Indian Archaeology'' (Volume 1). Edited by Amalananda Ghosh (1990). Massachusetts: Brill Academic Publishers. . * Emerson, D.T. (1998).

The Work of Jagdish Chandra Bose: 100 years of mm-wave research

'. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. * Emsley, John (2003). ''Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements''. England: Oxford University Press. . * Finger, Stanley (2001). ''Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations into Brain Function''. England: Oxford University Press. . * Flegg, Graham (2002). ''Numbers: Their History and Meaning''. Courier Dover Publications. . * Forbes, Duncan (1860). ''The History of Chess: From the Time of the Early Invention of the Game in India Till the Period of Its Establishment in Western and Central Europe''. London: W. H. Allen & co. * * Fraser, Gordon (2006). ''The New Physics for the Twenty-first Century''. England: Cambridge University Press. . * Gangopadhyaya, Mrinalkanti (1980). ''Indian Atomism: history and sources''. New Jersey: Humanities Press. . * Geddes, Patrick (2000). ''The life and work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose''. Asian Educational Services. . * Geyer, H. S. (2006), ''Global Regionalization: Core Peripheral Trends''. England: Edward Elgar Publishing. . * Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). ''An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology''. Brill. . * Ghosh, S.; Massey, Reginald; and Banerjee, Utpal Kumar (2006). ''Indian Puppets: Past, Present and Future''. Abhinav Publications. . * Gottsegen, Mark E. (2006). ''The Painter's Handbook: A Complete Reference''. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. . * Goonatilake, Susantha (1998). ''Toward a Global Science: Mining Civilizational Knowledge''. Indiana: Indiana University Press. . * Guillain, Jean-Yves (2004). ''Badminton: An Illustrated History''. Paris: Editions Publibook * Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (1998). ''Textiles, Costumes, and Ornaments of the Western Himalaya''. Indus Publishing. . * Hayashi, Takao (2005). ''Indian Mathematics'' in Flood, Gavin, ''The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism'', Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 616 pages, pp. 360375, 360375, . * Hershey, J. Willard (2004). ''The Book of Diamonds: Their Curious Lore, Properties, Tests and Synthetic Manufacture 1940''

''On the Use of Series in Hindu Mathematics''

Osiris 1: 606628. * Singh, Manpal (2005). ''Modern Teaching of Mathematics''. Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. * Singh, P. (1985). ''The So-called Fibonacci numbers in ancient and medieval India.'' Historia Mathematica 12(3), 22944. * Sircar, D.C. (1996).''Indian epigraphy''. Motilal Banarsidass. . * Sivaramakrishnan, V. M. (2001). ''Tobacco and Areca Nut''.

''Wootz Steel: An Advanced Material of the Ancient World''. Bangalore: Indian Institute of Science.

* Srinivasan, S. ''Wootz crucible steel: a newly discovered production site in South India''. Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 5 (1994), pp. 4961. * Srinivasan, S. and Griffiths, D. ''South Indian wootz: evidence for high-carbon steel from crucibles from a newly identified site and preliminary comparisons with related finds''. Material Issues in Art and Archaeology-V, Materials Research Society Symposium Proceedings Series Vol. 462. * * * Stein, Burton (1998). ''A History of India''. Blackwell Publishing. . * Stepanov, Serguei A. (1999). ''Codes on Algebraic Curves''. Springer. . * Stillwell, John (2004). ''Mathematics and its History (2 ed.)''. Berlin and New York: Springer. . * Taguchi, Genichi & Jugulum, Rajesh (2002). ''The Mahalanobis-taguchi Strategy: A Pattern Technology System''. John Wiley and Sons. . * Teresi, Dick; et al. (2002). ''Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science—from the Babylonians to the Maya''. New York: Simon & Schuster. . * Thomas, Arthur (2007) ''Gemstones: Properties, Identification and Use''. London: New Holland Publishers. * Thrusfield, Michael (2007). ''Veterinary Epidemiology''. Blackwell Publishing. . * Upadhyaya, Bhagwat Saran (1954). ''The Ancient World''. Andhra Pradesh: The Institute of Ancient Studies Hyderabad. * Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (2005). ''History of Indian Theatre''. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. . * Wenk, Hans-Rudolf; et al. (2003). ''Minerals: Their Constitution and Origin''. England: Cambridge University Press. . * * * Whitelaw, Ian (2007). ''A Measure of All Things: The Story of Man and Measurement''.

Ancient India's Inventions In Science And Technology

Essays on Indian Science and Technology.

P. K. Ray, SCIENCE, CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT – A CONNECTED PHENOMENA, Everyman's Science Vol.

* ''History of Science in South Asia''

hssa-journal.org

. HSSA is a peer-reviewed, open-access, online journal for the history of science in India. {{DEFAULTSORT:Indian Inventions And Discoveries Inventions Lists of inventions or discoveries India science and technology-related lists Inventions and discoveries

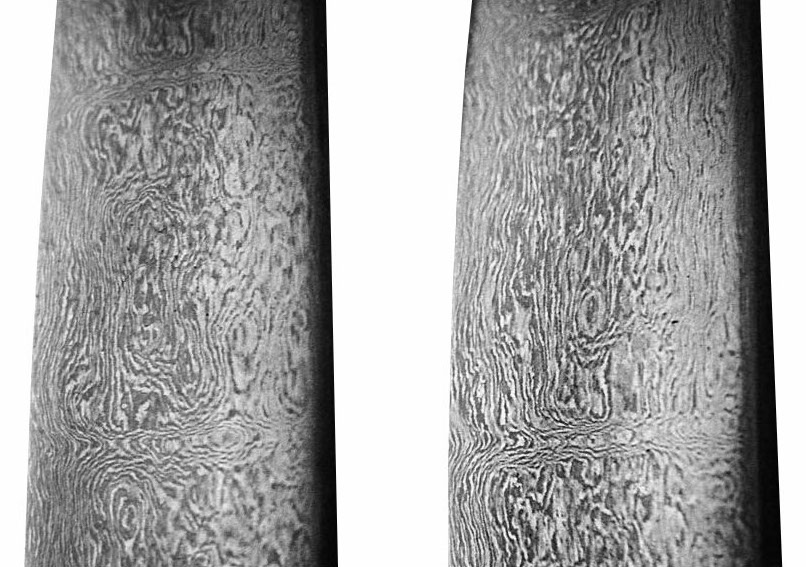

Wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon ...

: Wootz steel is an ultra-high carbon steel and the first form of crucible steel manufactured by the applications and use of nanomaterials

*

Nanomaterials describe, in principle, materials of which a single unit is sized (in at least one dimension) between 1 and 100 nm (the usual definition of nanoscale).

Nanomaterials research takes a materials science-based approach to n ...

in its microstructure and is characterised by its ultra-high carbon content exhibiting properties such as superplasticity and high impact hardness. Archaeological and Tamil language

Tamil (; ' , ) is a Dravidian language natively spoken by the Tamil people of South Asia. Tamil is an official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, the sovereign nations of Sri Lanka and Singapore, and the Indian territory o ...

literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to includ ...

evidence suggests that this manufacturing process was already in existence in South India well before the common era, with wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon ...

exported from the Chera dynasty and called ''Seric Iron'' in Rome, and later known as Damascus steel

Damascus steel was the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by ...

in Europe.Srinivasan 1994Srinivasan & Griffiths Reproduction research is undertaken by scientists Dr. Oleg Sherby and Dr. Jeff Wadsworth and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

have all attempted to create steels with characteristics similar to Wootz, but without success. J.D Verhoeven and Al Pendray attained some success in the reconstruction methods of production, proved the role of impurities of ore in the pattern creation, and reproduced Wootz steel with patterns microscopically and visually identical to one of the ancient blade patterns.

Music

*Musical Notation

Music notation or musical notation is any system used to visually represent aurally perceived music played with instruments or sung by the human voice through the use of written, printed, or otherwise-produced symbols, including notation f ...

: Samaveda

The Samaveda (, from ' "song" and ' "knowledge"), is the Veda of melodies and chants. It is an ancient Vedic Sanskrit text, and part of the scriptures of Hinduism. One of the four Vedas, it is a liturgical text which consists of 1,875 verses. A ...

text (1200 BC – 1000 BC) contains notated melodies, and these are probably the world's oldest surviving ones.Bruno Nettl, Ruth M. Stone, James Porter and Timothy Rice (1999), The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Routledge, , pages 242–245

Metrology

Crescograph

A crescograph is a device for measuring growth in plants. It was invented in the early 20th century by Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose.

The Bose crescograph uses a series of clockwork gears and a smoked glass plate to record the movement of the tip of ...

: The crescograph, a device for measuring growth in plants, was invented in the early 20th century by the Bengali scientist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contribution ...

.

* Incense clock: The incense clock is a timekeeping device used to measure minutes, hours, or days, incense clocks were commonly used at homes and temples in dynastic times. Although popularly associated with China the incense clock is believed to have originated in India, at least in its fundamental form if not function.Schafer (1963), pages 160161Bedini (1994), pages 6980 Early incense clocks found in China between the 6th and 8th centuries CE—the period it appeared in China all seem to have Devanāgarī

Devanagari ( ; , , Sanskrit pronunciation: ), also called Nagari (),Kathleen Kuiper (2010), The Culture of India, New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, , page 83 is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental writing system), based on the ...

carvings on them instead of Chinese seal characters. Incense itself was introduced to China from India in the early centuries CE, along with the spread of Buddhism by travelling monks.Bedini (1994), page 25Seiwert (2003), page 96Kumar, Yukteshwar (2005), page 65 Edward Schafer asserts that incense clocks were probably an Indian invention, transmitted to China, which explains the Devanāgarī inscriptions on early incense clocks found in China. Silvio Bedini

Silvio A. Bedini (January 17, 1917 – November 14, 2007) was an American historian, specialising in early scientific instruments. He was Historian Emeritus of the Smithsonian Institution, where he served on the professional staff for twenty-fiv ...

on the other hand asserts that incense clocks were derived in part from incense seals mentioned in Tantric Buddhist scriptures, which first came to light in China after those scriptures from India were translated into Chinese, but holds that the time-telling function of the seal was incorporated by the Chinese.

* Shearing Interferometer: Invented by M.V.R.K. Murty, a type of Lateral Shearing Interferometer utilises a laser source for measuring refractive index.

Science and technology

*Fibonacci number

In mathematics, the Fibonacci numbers, commonly denoted , form a sequence, the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the sum of the two preceding ones. The sequence commonly starts from 0 and 1, although some authors start the sequence from ...

: The Fibonacci numbers were first described in Indian mathematics, as early as 200 BC in work by Pingala on enumerating possible patterns of Sanskrit poetry formed from syllables of two lengths.

* Bipyrazole Organic Crystals, the piezoelectric molecules developed by IISER scientists recombine following mechanical fracture without any external intervention, autonomously self-healing in milliseconds with crystallographic precision.

* Digital

Digital usually refers to something using discrete digits, often binary digits.

Technology and computing Hardware

*Digital electronics, electronic circuits which operate using digital signals

** Digital camera, which captures and stores digital ...

vaccines

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified.

: Developed based on fundamental neurocognitive

Neurocognitive functions are cognitive functions closely linked to the function of particular areas, neural pathways, or cortical networks in the brain, ultimately served by the substrate of the brain's neurological matrix (i.e. at the cellular ...

computing

Computing is any goal-oriented activity requiring, benefiting from, or creating computing machinery. It includes the study and experimentation of algorithmic processes, and development of both hardware and software. Computing has scientific, ...

and immunological

Immunology is a branch of medicineImmunology for Medical Students, Roderick Nairn, Matthew Helbert, Mosby, 2007 and biology that covers the medical study of immune systems in humans, animals, plants and sapient species. In such we can see the ...

modulation

In electronics and telecommunications, modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform, called the '' carrier signal'', with a separate signal called the ''modulation signal'' that typically contains informat ...

discoveries in pediatric

Pediatrics ( also spelled ''paediatrics'' or ''pædiatrics'') is the branch of medicine that involves the medical care of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. In the United Kingdom, paediatrics covers many of their youth until the ...

and young adult populations, this sub field of digital therapeutics was invented by Bhargav Sri Prakash, through work led by his team at Carnegie Mellon University

Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) is a private research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. One of its predecessors was established in 1900 by Andrew Carnegie as the Carnegie Technical Schools; it became the Carnegie Institute of Technology ...

.

* e-mode HEMT, In 2019 scientists from Bangalore have developed a highly reliable, High Electron Mobility Transistor (HEMTs) that is a normally OFF device and can switch currents up to 4A and operates at 600V. This first-ever indigenous HEMT device made from gallium nitride (GaN). Such transistors are called e-mode or enhancement mode transistors.

* Nano Urea, the size of one nano urea liquid particle is 30 nanometre and compared to the conventional granular urea it has about 10,000 times more surface area to volume size. Due to the ultra-small size and surface properties, the nano urea liquid gets absorbed by plants more effectively when sprayed on their leaves.Ramesh Raliya of IFFCO is the inventor of nano urea.

* Locomotive