Ian Sinclair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ian McCahon Sinclair (born 10 June 1929) is a former Australian politician who served as leader of the National Party from 1984 to 1989. He was a government minister under six prime ministers, and later Speaker of the House of Representatives from March to November 1998.

Sinclair was born in

In 1965, Sinclair was appointed

In 1965, Sinclair was appointed

Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

and studied law at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

. He later bought a farming property near Tamworth. Sinclair was elected to parliament in 1963, and added to the ministry in 1965 as part of the Menzies Government. Over the following six years, he held various portfolios under four other prime ministers. Sinclair was elected deputy leader of his party in 1971, under Anthony. He was a senior member of the Fraser Government, spending periods as Minister for Primary Industry (1975–1979), Minister for Communications (1980–1982), and Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

(1982–1983). In 1984, Sinclair replaced Anthony as leader of the Nationals. He led the party to two federal elections, in 1984 and 1987, but was replaced by Charles Blunt

Charles William Blunt (born 19 January 1951) is a former Australian politician who served as leader of the National Party of Australia from 1989 to 1990.

Early life

Blunt was born in Sydney and graduated from the University of Sydney with a de ...

in 1989. Sinclair was father of the parliament from 1990 until his retirement at the 1998 election. He spent his last months in parliament as Speaker of the House of Representatives, following the sudden resignation of Bob Halverson; he is the only member of his party to have held the position. He also served as co-chair of the 1998 constitutional convention, alongside Barry Jones.

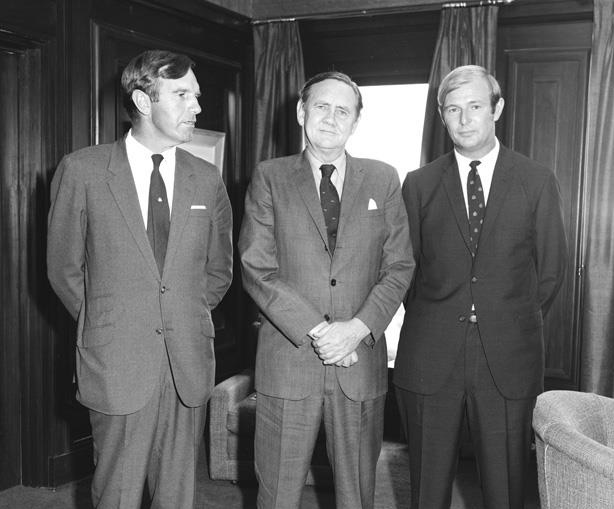

Along with Peter Nixon

Peter James Nixon AO (born 22 March 1928) is a former Australian politician and businessman. He served in the House of Representatives from 1961 to 1983, representing the Division of Gippsland as a member of the National Country Party (NCP). H ...

, Sinclair is one of two Country/Nationals MPs elected in the 1960s still alive, and he is the last surviving minister who served in the Menzies Government and the First Holt Ministry. He is entitled to the Right Honourable prefix as one of the few surviving Australian members of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

of the UK.

Early life

Sinclair was born inSydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

on 10 June 1929. He was the son of Gertrude Hazel (née Smith) and George McCahon Sinclair. His father was a chartered accountant who also served as deputy mayor of Ku-ring-gai Council

Ku-ring-gai Council is a local government area in Northern Sydney (Upper North Shore), in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The area is named after the Guringai Aboriginal people who were thought to be the traditional owners of the are ...

, chairman of Knox Grammar School, and an elder of the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

.

Sinclair attended Knox Grammar before going on to the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

, where he graduated Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

in 1949 and Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Ch ...

in 1952. He served in the No. 22 Squadron RAAF from 1950 to 1952, as part of the Citizen Air Force

The Air Force Reserve or RAAF Reserve is the common, collective name given to the reserve units of the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, ma ...

. Sinclair served his articles of clerkship with Norton Smith & Co., but did not pursue a legal career. He instead took up a grazing property near Bendemeer

Bendemeer () is a village of 485 people on the Macdonald River in the New England region of New South Wales, Australia. It is situated at the junction of the New England and Oxley Highways. Bendemeer is also famous for producing the numbe ...

and set up the Sinclair Pastoral Company, of which he became managing director. He was a director of the Farmers and Graziers' Co-operative Limited from 1962 to 1965.

Sinclair married Margaret Anne Tarrant in 1956, with whom he had one son and two daughters. She died of brain cancer in December 1967. He remarried on 14 February 1970 to Rosemary Fenton, who had been Miss Australia in 1960; they had one son together. His daughter Fiona married Liberal politician Peter King.

Political career

A member of the Country Party, Sinclair was appointed to theNew South Wales Legislative Council

The New South Wales Legislative Council, often referred to as the upper house, is one of the two chambers of the parliament of the Australian state of New South Wales. The other is the Legislative Assembly. Both sit at Parliament House in t ...

in 1961. He resigned in order to seek election to the House of Representatives at the 1963 federal election, retaining the Division of New England for the Country Party after the retirement of David Drummond.

Government minister

In 1965, Sinclair was appointed

In 1965, Sinclair was appointed Minister for Social Services

The Minister for Social Services is the Australian federal government minister who oversees Australian Government social services, including mental health, families and children's policy, and support for carers and people with disabilities, and ...

in the Menzies Government, replacing Hugh Roberton

Hugh Stevenson Roberton (18 December 1900 – 13 March 1987) was an Australian politician. A member of the Country Party, he served as Minister for Social Services in the Menzies government from 1956 to 1965. He later served as Ambassador ...

. He stood for the deputy leadership of the Country Party after the 1966 federal election, but was defeated by Doug Anthony

John Douglas Anthony, (31 December 192920 December 2020) was an Australian politician. He served as leader of the National Party of Australia from 1971 to 1984 and was the second and longest-serving Deputy Prime Minister, holding the position ...

. In 1968, he became Minister for Shipping and Transport in the Gorton Government. When Country Party leader John McEwen

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Australia, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt. He was the ...

retired in February 1971, Anthony was elected as his replacement and Sinclair defeated Peter Nixon

Peter James Nixon AO (born 22 March 1928) is a former Australian politician and businessman. He served in the House of Representatives from 1961 to 1983, representing the Division of Gippsland as a member of the National Country Party (NCP). H ...

for the deputy leadership. He was appointed Minister for Primary Industry. A month later, William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, ...

replaced John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

as Liberal leader and prime minister. McMahon wanted Sinclair to become Minister for Foreign Affairs, but for various reasons had to keep him in the primary industry portfolio and appoint Les Bury as foreign minister instead. Sinclair did later serve as acting foreign minister in Bury's absence.

In 1973, Sinclair was one of the six Country MPs to vote in favour of John Gorton's motion calling for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. After spending the three years of the Whitlam Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

government in opposition, he again became Minister for Primary Industry in 1975, in the Fraser Government. In 1977, Sinclair was appointed to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

.

In 1978, New South Wales Attorney-General Frank Walker appointed Michael Finnane to inquire into the financial dealings of Sinclair's father George, who had died in January 1976. The Finnane Report, which was tabled in the Parliament of New South Wales on 27 September 1979, alleged that Ian Sinclair had improperly loaned himself money from companies he controlled, attempted to conceal the loans, and forged his father's signature on company returns. As a result, Sinclair resigned from the ministry. His supporters criticised the report on several grounds, including that the inquiry was conducted in secret, that its release prejudiced Sinclair's right to a fair trial, and that it was politically biased as both Walker and Finnane were members of the ALP.

In April 1980, Sinclair was charged with nine counts of fraud, relating to forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which ...

, uttering

Uttering is a crime involving a person with the intent to defraud that knowingly sells, publishes or passes a forged or counterfeited document. More specifically, forgery creates a falsified document and uttering is the act of knowingly passing ...

, and making false statements on company returns. He was found not guilty on all charges on 15 August 1980, following a 23-day trial in the District Court of New South Wales.

Sinclair returned to the ministry in August 1980 as Minister for Special Trade Representations. After the 1980 election he was made Minister for Communications. He was finally made Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

in May 1982, holding the position until the government's defeat at the 1983 election.

Party leader

Doug Anthony announced his resignation as NCP leader in December 1983. Sinclair was elected as his replacement on 17 January 1984, defeating Stephen Lusher by an unspecified margin. In an interview with ''Australian Playboy

''Australian Playboy'' was an Australian imprint of ''Playboy'' magazine, running between 1979 and 2000, during which time 252 issues were published.

Content

In 1979 Kerry Packer's ACP Magazines secured the Australian rights to ''Playboy'' mag ...

'' in July 1984, Sinclair acknowledged a previous extramarital relationship with socialite Glen-Marie North. Copies of the interview were distributed in his electorate during the 1984 election campaign. In the lead-up to the election, Sinclair controversially attributed the spread of HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ...

in Australia to the Labor Party's recognition of de facto relationships and normalisation of homosexuality. After the deaths of three babies from HIV-contaminated blood transfusions, he stated that "if it wasn't for the promotion of homosexuality as a norm by Labor, I am quite confident that the very tragic and sad passing on of the AIDS disease ..to those three poor babies would not have occurred.

In 1985, Sinclair came into conflict with the National Farmers' Federation over his claims that the organisation did not have the support of farmers. He also came into conflict with the Liberal Party on a number of occasions. He publicly rejected calls for a Liberal–National party merger

The Liberal–National Coalition, commonly known simply as "the Coalition" or informally as the LNP, is an alliance of centre-right political parties that forms one of the two major groupings in Australian federal politics. The two partners in ...

, citing the incompatibility of the National Party's conservatism and the "small-l liberal" wing of the Liberal Party. In March 1986, he accused Liberals of undermining the leadership of John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

and thereby harming the Coalition's chances of victory. He denounced former Liberal prime minister Malcolm Fraser's support of sanctions against apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

South Africa, accusing him of "prejudice against Southern Africa and the whites there". Sinclair proclaimed a "deep abhorrence" of apartheid, but believed the sanctions were too "heavy-handed". He supported the re-admission of South Africa to the United Nations, the lifting of the sporting boycott, the re-establishment of an Australian trade commission, and direct flights between Australia and South Africa.

In addition to his leadership of the National Party, Sinclair continued to be the opposition spokesman on defence. In August 1986, he suggested the formation of a Pacific trade bloc at a meeting of the International Democrat Union in Sydney. The proposal, also supported by shadow foreign minister Andrew Peacock, was designed to "minimise the harmful policies of major protectionist trading nations" like the U.S. and the European Communities

The European Communities (EC) were three international organizations that were governed by the same set of institutions. These were the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom), and the ...

. Later in the year, Sinclair questioned the value of ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS or ANZUS Treaty) is a 1951 non-binding collective security agreement between Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States, to co-operate on milita ...

, stating that Australia should reconsider its commitments to New Zealand as it had become too isolationist. He also believed Australia should adopt a more assertive role than provided for in the Dibb Report The Dibb Report (Review of Australia's Defence Capabilities) was an influential review of Australia's defence plans. While the report's recommendations were not fully accepted by the Hawke government, they led to significant changes in Australia's ...

. He opposed trade sanctions on Fiji following the 1987 coups d'état and was accused by foreign minister Bill Hayden

William George Hayden (born 23 January 1933) is an Australian politician who served as the 21st governor-general of Australia from 1989 to 1996. He was Leader of the Labor Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1977 to 1983, and served as ...

of sympathising with the perpetrators.

In the lead-up to the 1987 election, Sinclair dealt with the "Joh for Canberra

The Joh for Canberra campaign, initially known as the Joh for PM campaign, was an attempt by Queensland National Party premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen to become Prime Minister of Australia. The campaign was announced in January 1987 and drew sub ...

" campaign, an ambitious bid by Queensland premier and state National leader Joh Bjelke-Petersen to enter federal politics and become prime minister. The campaign "derailed any semblance of non-Labor unity from the beginning of 1987", and resulting in the Coalition splitting. After the election, the Queensland branch continued its efforts to oust Sinclair from the leadership.

In the late 1980s, Sinclair was drawn into the debate over the levels of Asian immigration to Australia, favouring a reduction in the number of Asians allowed into the country. In August 1988, he said:

"What we are saying is that if there is any risk of an undue build-up of Asians as against others in the community, then you need to control it ... I certainly believe, that at the moment we need ... to reduce the number of Asians ... We don't want the divisions of South Africa, we don't want the divisions of London. We really don't want the colour divisions of the United States."A few days later he "toned down his statements" at the request of Howard and denied that he had specifically targeted Asians. The following month, following pressure from Howard, he sacked National Senate leader John Stone from the shadow ministry for making similar comments, "with regret". This was seen by many in his party as a capitulation to the Liberals. In May 1989, there were simultaneous leadership challenges in both Coalition parties, with Peacock displacing Howard as Liberal leader and

Charles Blunt

Charles William Blunt (born 19 January 1951) is a former Australian politician who served as leader of the National Party of Australia from 1989 to 1990.

Early life

Blunt was born in Sydney and graduated from the University of Sydney with a de ...

replacing Sinclair. The immediate trigger for Sinclair's defeat was dissatisfaction with his conditional support for the Hawke Government's deregulation of the wheat industry. However, there was also a sense that it was time for a generational change in the party leadership. When Blunt lost his seat at the 1990 election, Sinclair made an attempt to regain the NPA leadership, but was defeated by Tim Fischer

Timothy Andrew Fischer (3 May 1946 – 22 August 2019) was an Australian politician and diplomat who served as leader of the National Party from 1990 to 1999. He was Deputy Prime Minister in the Howard Government from 1996 to 1999.

Fischer ...

, and retired to the back bench. He was thus the first NPA leader since the formation of the Coalition to have never served as Deputy Prime Minister of Australia

The deputy prime minister of Australia is the deputy chief executive and the second highest ranking officer of the Australian Government. The office of deputy prime minister was officially created as a ministerial portfolio in 1968, althoug ...

.

Post-leadership

Sinclair underwent a double heart bypass surgery in September 1991. On 23 March 1993, ten days after the Coalition lost the 1993 federal election, Sinclair unsuccessfully challengedTim Fischer

Timothy Andrew Fischer (3 May 1946 – 22 August 2019) was an Australian politician and diplomat who served as leader of the National Party from 1990 to 1999. He was Deputy Prime Minister in the Howard Government from 1996 to 1999.

Fischer ...

for the party leadership.

By 1993, Sinclair was the Father of the House

Father of the House is a title that has been traditionally bestowed, unofficially, on certain members of some legislatures, most notably the House of Commons in the United Kingdom. In some legislatures the title refers to the longest continuously ...

, the only sitting MP to have served with Robert Menzies, and "the last of the Right Honourables" (MPs with membership in the Privy Council). He was seen as a candidate for the speakership if the Coalition won the 1993 election, however this did not eventuate. Aged nearly 70, Sinclair announced his intention to retire from parliament at the 1998 election. In February 1998 Howard appointed Sinclair as Chairman of the Constitutional Convention, which debated the possibility of Australia becoming a republic. When Speaker Bob Halverson suddenly resigned in March, Sinclair was elected to replace him. He served as speaker for the last seven months of his term, during which he usually wore an academic-style gown. At the time of his retirement, he was the last parliamentary survivor of the Menzies, Holt

Holt or holte may refer to:

Natural world

*Holt (den), an otter den

* Holt, an area of woodland

Places Australia

* Holt, Australian Capital Territory

* Division of Holt, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives in Vic ...

, Gorton and McMahon

McMahon, also spelled MacMahon (older Irish orthography: ; reformed Irish orthography: ), is a surname of Irish origin. It is derived from the Gaelic ''Mac'' ''Mathghamhna'' meaning 'son of the bear'.

The surname came into use around the 11th ce ...

governments.

As a result of his election as Speaker, Sinclair wanted to remain in Parliament, in the event of the re-election of the Howard Government, in order to continued as Speaker.

However Sinclair had announced his retirement before Halverson's resignation as Speaker and the National Party had since selected Stuart St. Clair as his replacement in New England.

Sinclair's retirement could not be reversed and St. Clair refused to stand aside for him. St. Clair ultimately succeeded Sinclair at the 1998 election.

After politics

In January 2001, he was appointed a Companion of theOrder of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Go ...

(AC). As of 2009, Sinclair was the President of AUSTCARE, an international, non-profit, independent aid organisation. In 2000, Sinclair became the inaugural chairman of the Foundation for Rural and Regional Renewal (FRRR), a non-profit organisation which issues grants to regional communities. He retired in June 2019 and was succeeded by Tim Fairfax. Sinclair also served for several years as the Honorary President of the Scout Association of Australia, New South Wales Branch, retiring in 2019. He received Scouts’ National Presidents Award on World Scout Day 2020.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sinclair, Ian 1929 births Living people Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Members of the Cabinet of Australia Companions of the Order of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for New England Members of the Australian House of Representatives Leaders of the Australian House of Representatives People educated at Knox Grammar School Speakers of the Australian House of Representatives People from Tamworth, New South Wales National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of New South Wales Members of the New South Wales Legislative Council Defence ministers of Australia Leaders of the National Party of Australia 20th-century Australian politicians Government ministers of Australia