Iron curtain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing

In the 19th century, iron safety curtains were installed on theater stages to slow the spread of fire.

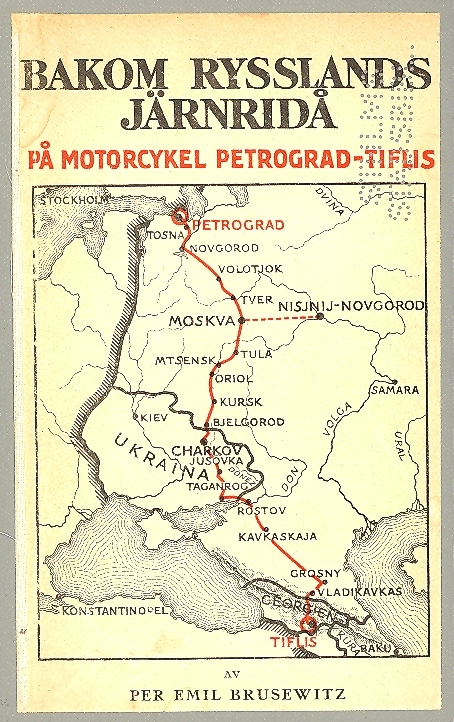

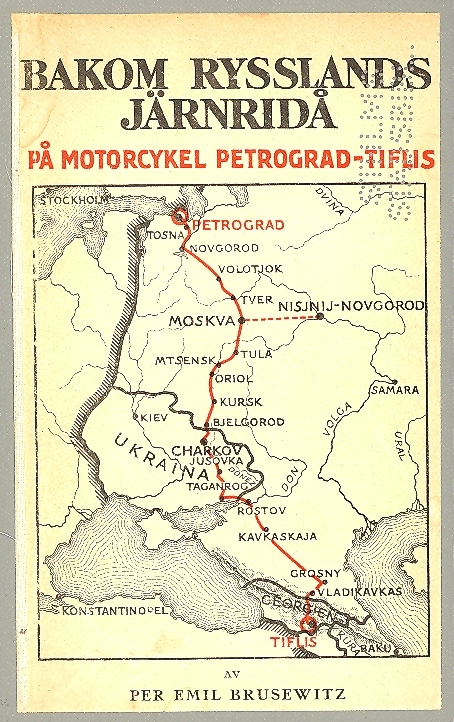

Perhaps the first recorded application of the term "iron curtain" to

In the 19th century, iron safety curtains were installed on theater stages to slow the spread of fire.

Perhaps the first recorded application of the term "iron curtain" to

The antagonism between the Soviet Union and the West that came to be described as the "iron curtain" had various origins.

During the summer of 1939, after conducting negotiations both with a British-French group and with

The antagonism between the Soviet Union and the West that came to be described as the "iron curtain" had various origins.

During the summer of 1939, after conducting negotiations both with a British-French group and with

Much of the Western public still regarded the

Much of the Western public still regarded the

While the Iron Curtain remained in place, much of Eastern Europe and parts of Central Europe (except

While the Iron Curtain remained in place, much of Eastern Europe and parts of Central Europe (except

To the west of the Iron Curtain, the countries of Western Europe, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe – along with

To the west of the Iron Curtain, the countries of Western Europe, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe – along with

One of the conclusions of the

One of the conclusions of the

The inner German border was marked in rural areas by double fences made of steel mesh (expanded metal) with sharp edges, while near urban areas a high concrete barrier similar to the Berlin Wall was built. The installation of the Wall in 1961 brought an end to a decade during which the divided capital of divided Germany was one of the easiest places to move west across the Iron Curtain.

The barrier was always a short distance inside East German territory to avoid any intrusion into Western territory. The actual borderline was marked by posts and signs and was overlooked by numerous watchtowers set behind the barrier. The strip of land on the West German side of the barrier – between the actual borderline and the barrier – was readily accessible but only at considerable personal risk, because it was patrolled by both East and West German border guards.

Several villages, many historic, were destroyed as they lay too close to the border, for example Erlebach. Shooting incidents were not uncommon, and several hundred civilians and 28 East German border guards were killed between 1948 and 1981 (some may have been victims of "

The inner German border was marked in rural areas by double fences made of steel mesh (expanded metal) with sharp edges, while near urban areas a high concrete barrier similar to the Berlin Wall was built. The installation of the Wall in 1961 brought an end to a decade during which the divided capital of divided Germany was one of the easiest places to move west across the Iron Curtain.

The barrier was always a short distance inside East German territory to avoid any intrusion into Western territory. The actual borderline was marked by posts and signs and was overlooked by numerous watchtowers set behind the barrier. The strip of land on the West German side of the barrier – between the actual borderline and the barrier – was readily accessible but only at considerable personal risk, because it was patrolled by both East and West German border guards.

Several villages, many historic, were destroyed as they lay too close to the border, for example Erlebach. Shooting incidents were not uncommon, and several hundred civilians and 28 East German border guards were killed between 1948 and 1981 (some may have been victims of "

File:Grensovergang-helmstedt-marienborn-paspoortcontrole-personenautos-04.JPG

File:Grensovergang-helmstedt-marienborn-paspoortcontrole-vrachtautos.JPG

File:Grensovergang-helmstedt-marienborn-lichtmast-commandotoren-brug.JPG

File:Grensovergang-helmstedt-marienborn-lichtmast-02.JPG

p.221

Speaking at the Berlin Wall on 12 June 1987, Reagan challenged Gorbachev to go further, saying "General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!" In February 1989, the Hungarian

Google Print, p.4

/ref> The opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on 19 August 1989 then set in motion a chain reaction, at the end of which there was no longer a GDR and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated. The idea of opening the border at a ceremony came from

File:Oliver Mark - Otto Habsburg-Lothringen, Pöcking 2006.jpg,

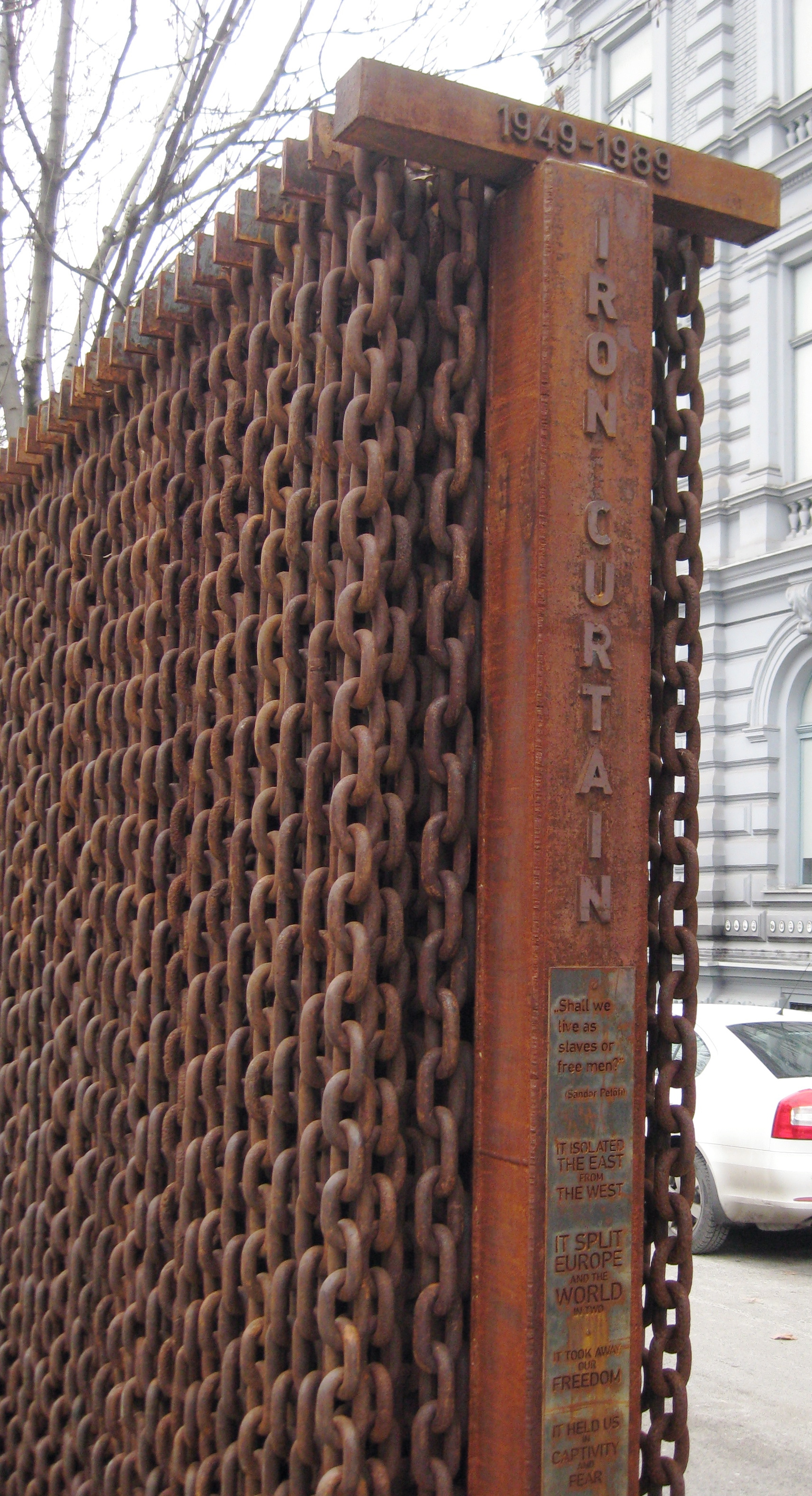

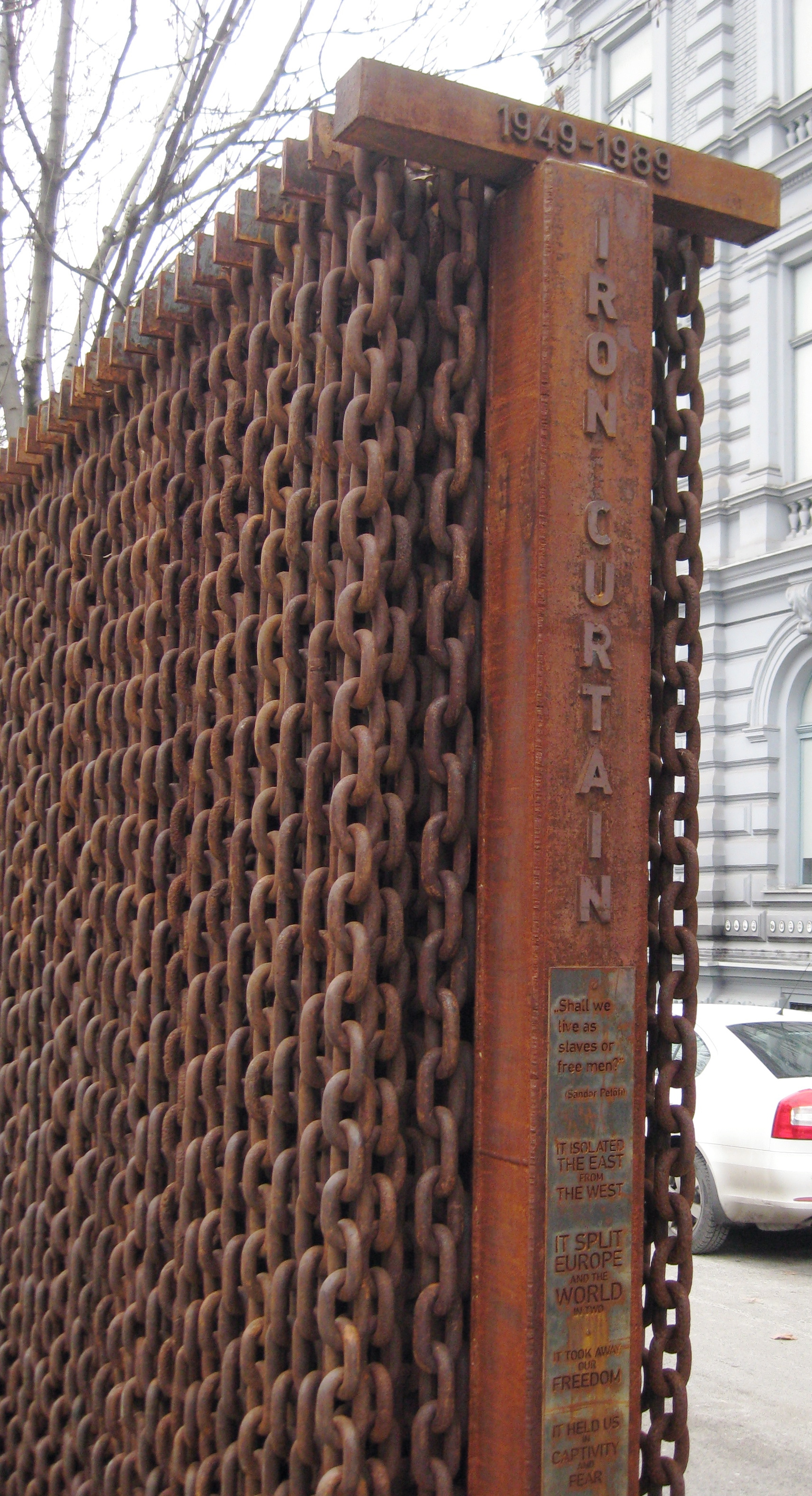

There is an Iron Curtain monument in the southern part of the Czech Republic at approximately . A few hundred meters of the original fence, and one of the guard towers, has remained installed. There are interpretive signs in Czech and English that explain the history and significance of the Iron Curtain. This is the only surviving part of the fence in the Czech Republic, though several guard towers and bunkers can still be seen. Some of these are part of the Communist Era defences, some are from the never-used Czechoslovak border fortifications in defence against

There is an Iron Curtain monument in the southern part of the Czech Republic at approximately . A few hundred meters of the original fence, and one of the guard towers, has remained installed. There are interpretive signs in Czech and English that explain the history and significance of the Iron Curtain. This is the only surviving part of the fence in the Czech Republic, though several guard towers and bunkers can still be seen. Some of these are part of the Communist Era defences, some are from the never-used Czechoslovak border fortifications in defence against

Freedom Without Walls: German Missions in the United States

��Looking Back at the Fall of the Berlin Wall – official homepage in English

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070927185810/http://opal.kent.ac.uk/cartoonx-cgi/ccc.py?mode=single&start=1&search=iron%20curtain "Peep under the Iron Curtain" a cartoon first published on 6 March 1946 in the ''

Field research along the northern sections of the former German-German border, with detailed maps, diagrams, and photos

* S-175 "Gardina (The Curtain)"—Main type of electronic security barrier on the Soviet borders

Remnants of the Iron Curtain along the Greek-Bulgarian border, the Iron Curtain's Southernmost part

Iron Curtain

at the ''

The Berlin Wall: A Secret History

at History Today

Historic film footage of Winston Churchill's "Iron Curtain" speech (from "Sinews of Peace" address) at Westminster College, 1946

''DIE NARBE DEUTSCHLAND''

��A 16-hour-long experimental single shot documentary showing the former Iron Curtain running through Germany in its entirety from above, 2008–2014 * 03"On This Day: Berlin Wall falls"; 04"Untangling 5 myths about the Berlin Wall". Chicago Tribune. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014; 05"In Photos: 25 years ago today the Berlin Wall Fell". TheJournal.i.e. 9 November 2014. {{Authority control 1940s neologisms Aftermath of World War II Cold War terminology Joseph Stalin Cold War speeches Speeches by Winston Churchill Political metaphors Eastern Bloc Foreign relations of the Soviet Union 1946 in international relations 1991 disestablishments Cold War in popular culture 1946 speeches 1946 introductions

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

into two separate areas from the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR) to block itself and its satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbitin ...

s from open contact with the West, its allies and neutral states. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were the countries that were connected to or influenced by the Soviet Union, while on the west side were the countries that were NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

members, or connected to or influenced by the United States; or nominally neutral. Separate international economic and military alliances were developed on each side of the Iron Curtain. It later became a term for the physical barrier of fences, walls, minefields, and watchtowers that divided the "east" and "west". The Berlin Wall was also part of this physical barrier.

The nations to the east of the Iron Curtain were Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

, East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

, Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the ...

, and the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

; however, East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

have since ceased to exist. Countries that made up the USSR were Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

, Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and t ...

, Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnist ...

, Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

, Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

, Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the ea ...

, Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

, Lithuania, Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

, and Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

. The events that demolished the Iron Curtain started with peaceful opposition in Poland, and continued into Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

, East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

, and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Romania became the only socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term ''communist state'' is ofte ...

in Europe to overthrow its government with violence.

The use of the term "Iron Curtain" as a metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide (or obscure) clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared wit ...

for strict separation goes back at least as far as the early 19th century. It originally referred to fireproof curtains in theaters. The author Alexander Campbell used the term metaphorically in his 1945 book ''It's Your Empire'', describing "an iron curtain of silence and censorship hichhas descended since the Japanese conquests of 1942". Its popularity as a Cold War symbol is attributed to its use in a speech Winston Churchill gave on 5 March 1946, in Fulton, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

.

On the one hand, the Iron Curtain was a separating barrier between the power blocs and, on the other hand, natural biotypes were formed here, as the European Green Belt shows today, or original cultural, ethnic or linguistic areas such as the area around Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into pr ...

were preserved.

Pre-Cold War usage

In the 19th century, iron safety curtains were installed on theater stages to slow the spread of fire.

Perhaps the first recorded application of the term "iron curtain" to

In the 19th century, iron safety curtains were installed on theater stages to slow the spread of fire.

Perhaps the first recorded application of the term "iron curtain" to Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

was in Vasily Rozanov

Vasily Vasilievich Rozanov (russian: Васи́лий Васи́льевич Рóзанов; – 5 February 1919) was one of the most controversial Russian writers and important philosophers in the symbolists' of the pre- revolutionary epoc ...

's 1918 polemic ''The Apocalypse of Our Time''. It is possible that Churchill read it there following the publication of the book's English translation in 1920. The passage runs:

In 1920, Ethel Snowden, in her book ''Through Bolshevik Russia'', used the term in reference to the Soviet border.

A May 1943 article in ''Signal

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The '' IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing' ...

'', a German propaganda periodical, discussed "the iron curtain that more than ever before separates the world from the Soviet Union". Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

commented in '' Das Reich'', on 25 February 1945, that if Germany should lose the war, "An iron curtain would fall over this enormous territory controlled by the Soviet Union, behind which nations would be slaughtered". German foreign minister Lutz von Krosigk

Johann Ludwig "Lutz" Graf Schwerin von Krosigk (Born Johann Ludwig von Krosigk; 22 August 18874 March 1977) was a German senior government official who served as the minister of Finance of Germany from 1932 to 1945 and ''de facto'' chancello ...

broadcast 2 May 1945: "In the East the iron curtain behind which, unseen by the eyes of the world, the work of destruction goes on, is moving steadily forward".

Churchill's first recorded use of the term "iron curtain" came in a 12 May 1945 telegram he sent to U.S. President Harry S. Truman regarding his concern about Soviet actions, stating " iron curtain is drawn down upon their front. We do not know what is going on behind".

He repeated it in another telegram to Truman on June 4, mentioning "...the descent of an iron curtain between us and everything to the eastward", and in a House of Commons speech on 16 August 1945, stating "it is not impossible that tragedy on a prodigious scale is unfolding itself behind the iron curtain which at the moment divides Europe in twain".

During the Cold War

Building antagonism

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

regarding potential military and political agreements, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the German–Soviet Commercial Agreement (which provided for the trade of certain German military and civilian equipment in exchange for Soviet raw materials) and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

(signed in late August 1939), named after the foreign secretaries of the two countries (Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February1890 – 8 November 1986) was a Russian politician and diplomat, an Old Bol ...

and Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

), which included a secret agreement to split Poland and Eastern Europe between the two states.

The Soviets thereafter occupied Eastern Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

(September 1939), Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

(June 1940), Lithuania (1940), northern Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

(Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of ...

and Northern Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berger ...

, late June 1940), Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and t ...

(1940) and eastern Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bo ...

(March 1940). From August 1939, relations between the West and the Soviets deteriorated further when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany engaged in an extensive economic relationship by which the Soviet Union sent Germany vital oil, rubber, manganese and other materials in exchange for German weapons, manufacturing machinery and technology. Nazi–Soviet trade ended in June 1941 when Germany broke the Pact and invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

.

In the course of World War II, Stalin determined to acquire a buffer area against Germany, with pro-Soviet states on its border in an Eastern bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. Stalin's aims led to strained relations at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

(February 1945) and the subsequent Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

(July–August 1945). People in the West expressed opposition to Soviet domination over the buffer states, and the fear grew that the Soviets were building an empire that might be a threat to them and their interests.

Nonetheless, at the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, the Allies assigned parts of Poland, Finland, Romania, Germany, and the Balkans to Soviet control or influence. In return, Stalin promised the Western Allies that he would allow those territories the right to national self-determination. Despite Soviet cooperation during the war, these concessions left many in the West uneasy. In particular, Churchill feared that the United States might return to its pre-war isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangle ...

, leaving the exhausted European states unable to resist Soviet demands. (President Franklin D. Roosevelt had announced at Yalta that after the defeat of Germany, U.S. forces would withdraw from Europe within two years.)

Churchill speech

Winston Churchill's "Sinews of Peace" address of 5 March 1946, at Westminster College inFulton, Missouri

Fulton is the largest city in and the county seat of Callaway County, Missouri, United States. Located about northeast of Jefferson City and the Missouri River and east of Columbia, the city is part of the Jefferson City, Missouri, Metropolita ...

, used the term "iron curtain" in the context of Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe:

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

as a close ally in the context of the recent defeat of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and of Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent for ...

. Although not well received at the time, the phrase ''iron curtain'' gained popularity as a shorthand reference to the division of Europe as the Cold War strengthened. The Iron Curtain served to keep people in, and information out. People throughout the West eventually came to accept and use the metaphor.

Churchill's "Sinews of Peace" address strongly criticised the Soviet Union's exclusive and secretive tension policies along with the Eastern Europe's state form, Police State

A police state describes a state where its government institutions exercise an extreme level of control over civil society and liberties. There is typically little or no distinction between the law and the exercise of political power by the ...

(''Polizeistaat''). He expressed the Allied Nations' distrust of the Soviet Union after the World War II. In September 1946, US-Soviet cooperation collapsed due to the US disavowal of the Soviet Union's opinion on the German problem in the Stuttgart Council, and then followed the announcement by US President Harry S. Truman of a hard line anti-Soviet, anticommunist policy. After that the phrase became more widely used as an anti-Soviet term in the West.

Additionally, Churchill mentioned in his speech that regions under the Soviet Union's control were expanding their leverage and power without any restriction. He asserted that in order to put a brake on this ongoing phenomenon, the commanding force and strong unity between the UK and the US was necessary.

Stalin took note of Churchill's speech and responded in ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' soon afterward. He accused Churchill of warmongering, and defended Soviet "friendship" with eastern European states as a necessary safeguard against another invasion. Stalin further accused Churchill of hoping to install right-wing governments in eastern Europe with the goal of agitating those states against the Soviet Union. Andrei Zhdanov

Andrei Aleksandrovich Zhdanov ( rus, Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Жда́нов, p=ɐnˈdrej ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐdanəf, links=yes; – 31 August 1948) was a Soviet politician and cultural ideologist. After World War ...

, Stalin's chief propagandist, used the term against the West in an August 1946 speech:

Political, economic, and military realities

Eastern Bloc

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German language, German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constit ...

, Switzerland, and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

) found themselves under the hegemony of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. The Soviet Union annexed:

* Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and t ...

* Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

Senn, Alfred Erich, ''Lithuania 1940: Revolution from Above'', Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007

* Lithuania

as Soviet Socialist Republics within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

.

Germany effectively gave Moscow a free hand in much of these territories in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

of 1939, signed before Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

Other Soviet-annexed territories included:

* Eastern Poland

Eastern Poland is a macroregion in Poland comprising the Lublin, Podkarpackie, Podlaskie, Świętokrzyskie, and Warmian-Masurian voivodeships.

The make-up of the distinct macroregion is based not only of geographical criteria, but also economic ...

(incorporated into the Ukrainian and Byelorussian SSRs),

* Part of eastern Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bo ...

(became part of the Karelo-Finnish SSR

The Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic (Karelo-Finnish SSR; fi, ; rus, Каре́ло-Фи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респу́блика, r=Karelo-Finskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Resp ...

)Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline, ''Stalin's Cold War'', New York: Manchester University Press, 1995,

* Northern Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

(part of which became the Moldavian SSR

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic ( ro, Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească, Moldovan Cyrillic: ) was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union which existed from 1940 to 1991. The republic was formed on 2 August 1940 ...

).

*Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and admini ...

, the northern half of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1 ...

, taken in 1945.

*Part of eastern Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

(Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

, incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR).

Between 1945 and 1949 the Soviets converted the following areas into satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbitin ...

s:

* The German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

* The People's Republic of Bulgaria

The People's Republic of Bulgaria (PRB; bg, Народна Република България (НРБ), ''Narodna Republika Balgariya, NRB'') was the official name of Bulgaria, when it was a socialist republic from 1946 to 1990, ruled by the ...

* The People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

* The Hungarian People's Republic

The Hungarian People's Republic ( hu, Magyar Népköztársaság) was a one-party socialist state from 20 August 1949

to 23 October 1989.

It was governed by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which was under the influence of the Soviet U ...

Granville, Johanna, ''The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956'', Texas A&M University Press, 2004.

* The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

* The People's Republic of Romania

The Socialist Republic of Romania ( ro, Republica Socialistă România, RSR) was a Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state that existed officially in Romania from 1947 to 1989. From 1947 to 1965, the state was known as the Romanian Peop ...

* The People's Republic of Albania

The People's Socialist Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë, links=no) was the Marxist–Leninist one party state that existed in Albania from 1946 to 1992 (the official name of the country was the People's R ...

(which re-aligned itself in the 1950s and early 1960s away from the Soviet Union towards the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, sli ...

(PRC) and split from the PRC towards a strongly isolationist worldview in the late 1970s)

Soviet-installed governments ruled the Eastern Bloc countries, with the exception of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Y ...

, which changed its orientation away from the Soviet Union in the late 1940s to a progressively independent worldview.

The majority of European states to the east of the Iron Curtain developed their own international economic and military alliances, such as Comecon

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (, ; English abbreviation COMECON, CMEA, CEMA, or CAME) was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along wi ...

and the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

.

West of the Iron Curtain

To the west of the Iron Curtain, the countries of Western Europe, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe – along with

To the west of the Iron Curtain, the countries of Western Europe, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe – along with Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German language, German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constit ...

and Switzerland – operated market economies

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers a ...

. With the exception of a period of fascism in Spain

Falangism ( es, falangismo) was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS) and afterwards the F ...

(until 1975

It was also declared the ''International Women's Year'' by the United Nations and the European Architectural Heritage Year by the Council of Europe.

Events

January

* January 1 - Watergate scandal (United States): John N. Mitchell, H. R. ...

) and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

(until 1974

Major events in 1974 include the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis and the resignation of President of the United States, United States President Richard Nixon following the Watergate scandal. In the Middle East, the aftermath of the 1973 Yom K ...

) and a military dictatorship in Greece (1967–1974), democratic governments ruled these countries.

Most of the states of Europe to the west of the Iron Curtain – with the exception of neutral Switzerland, Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German language, German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constit ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Sweden, Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bo ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern ...

– allied themselves with Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

within NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

was a unique anomaly in that it stayed neutral and non-aligned until 1982, when, following democracy's return, it joined NATO. Economically, the European Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

(EC) and the European Free Trade Association

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is a regional trade organization and free trade area consisting of four European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. The organization operates in parallel with the European ...

represented Western counterparts to COMECON

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (, ; English abbreviation COMECON, CMEA, CEMA, or CAME) was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along wi ...

. Most of the nominally neutral states were economically closer to the United States than they were to the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

.

Further division in the late 1940s

In January 1947,Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Frankli ...

appointed General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

as Secretary of State, scrapped Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) directive 1067 (which embodied the Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan was a proposal to eliminate Germany following World War II and eliminating its arms industry and removing or destroying other key industries basic to military strength. This included the removal or destruction of all industri ...

), and supplanted it with JCS 1779, which decreed that an orderly and prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany." Officials met with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February1890 – 8 November 1986) was a Russian politician and diplomat, an Old Bol ...

and others to press for an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, goods and infrastructure already removed by the Soviets.

After five and a half weeks of negotiations, Molotov refused the demands and the talks were adjourned. Marshall was particularly discouraged after personally meeting with Stalin, who expressed little interest in a solution to German economic problems. The United States concluded that a solution could not wait any longer. In a 5 June 1947 speech,Marshall, George C, ''The Marshal Plan Speech'', 5 June 1947 Marshall announced a comprehensive program of American assistance to all European countries wanting to participate, including the Soviet Union and those of Eastern Europe, called the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

.

Stalin opposed the Marshall Plan. He had built up the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

protective belt of Soviet-controlled nations on his Western border, and wanted to maintain this buffer zone of states combined with a weakened Germany under Soviet control. Fearing American political, cultural and economic penetration, Stalin eventually forbade Soviet Eastern bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

countries of the newly formed Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist-Leninist communist parties in Europe during the early Cold War that was formed in part as a replacement of the ...

from accepting Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

aid. In Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, that required a Soviet-backed Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repub ...

,''Airbridge to Berlin'', "Eye of the Storm" chapter the brutality of which shocked Western powers more than any event so far and set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.

Relations further deteriorated when, in January 1948, the U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

also published a collection of documents titled ''Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939 – 1941: Documents from the Archives of The German Foreign Office'', which contained documents recovered from the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

revealing Soviet conversations with Germany regarding the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, including its secret protocol dividing eastern Europe, the 1939 German-Soviet Commercial Agreement, and discussions of the Soviet Union potentially becoming the fourth Axis Power. In response, one month later, the Soviet Union published '' Falsifiers of History'', a Stalin-edited and partially re-written book attacking the West.

After the Marshall Plan, the introduction of a new currency to Western Germany to replace the debased Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

and massive electoral losses for communist parties, in June 1948, the Soviet Union cut off surface road access to Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

, initiating the Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, ro ...

, which cut off all non-Soviet food, water and other supplies for the citizens of the non-Soviet sectors of Berlin. Because Berlin was located within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, the only available methods of supplying the city were three limited air corridors. A massive aerial supply campaign was initiated by the United States, Britain, France, and other countries, the success of which caused the Soviets to lift their blockade in May 1949.

Emigration restrictions

One of the conclusions of the

One of the conclusions of the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

was that the western Allies would return all Soviet citizens who found themselves in their zones to the Soviet Union. This affected the liberated Soviet prisoners of war (branded as traitors), forced laborers, anti-Soviet collaborators with the Germans, and anti-communist refugees.

Migration from east to west of the Iron Curtain, except under limited circumstances, was effectively halted after 1950. Before 1950, over 15 million people (mainly ethnic Germans) emigrated from Soviet-occupied eastern European countries to the west in the five years immediately following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. However, restrictions implemented during the Cold War stopped most east–west migration, with only 13.3 million migrations westward between 1950 and 1990. More than 75% of those emigrating from Eastern Bloc countries between 1950 and 1990 did so under bilateral agreements for "ethnic migration."

About 10% were refugees permitted to emigrate under the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conv ...

of 1951. Most Soviets allowed to leave during this time period were ethnic Jews permitted to emigrate to Israel after a series of embarrassing defections in 1970 caused the Soviets to open very limited ethnic emigrations. The fall of the Iron Curtain was accompanied by a massive rise in European East-West migration.

Physical barrier

The Iron Curtain took physical shape in the form of border defences between the countries of western and eastern Europe. There were some of the most heavily militarised areas in the world, particularly the so-called "inner German border

The inner German border (german: Innerdeutsche Grenze or ; initially also ) was the border between the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany) and the West Germany, Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) from 1949 to 1990. Not ...

" – commonly known as ''die Grenze'' in German – between East and West Germany.

Elsewhere along the border between West and East, the defence works resembled those on the intra-German border. During the Cold War, the border zone in Hungary started from the border. Citizens could only enter the area if they lived in the zone or had a passport valid for traveling out. Traffic control points and patrols enforced this regulation.

Those who lived within the border-zone needed special permission to enter the area within of the border. The area was very difficult to approach and heavily fortified. In the 1950s and 1960s, a double barbed-wire fence was installed from the border. The space between the two fences was laden with land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automatic ...

s. The minefield was later replaced with an electric signal fence (about from the border) and a barbed wire fence, along with guard towers and a sand strip to track border violations. Regular patrols sought to prevent escape attempts. They included cars and mounted units. Guards and dog patrol units watched the border 24/7 and were authorised to use their weapons to stop escapees. The wire fence nearest the actual border was irregularly displaced from the actual border, which was marked only by stones. Anyone attempting to escape would have to cross up to before they could cross the actual border. Several escape attempts failed when the escapees were stopped after crossing the outer fence.

The creation of these highly militarised no-man's lands led to ''de facto'' nature reserves and created a wildlife corridor

A wildlife corridor, habitat corridor, or green corridor is an area of habitat (ecology), habitat connecting wildlife populations separated by human activities or structures (such as roads, development, or logging). This allows an exchange of i ...

across Europe; this helped the spread of several species to new territories. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, several initiatives are pursuing the creation of a European Green Belt nature preserve area along the Iron Curtain's former route. In fact, a long-distance cycling route

Long-distance cycling routes are designated cycling routes in various countries around the world for bicycle tourism. These routes include anything from longer rail trails, to national cycling route networks like the Dutch LF-routes,the French ...

along the length of the former border called the Iron Curtain Trail (ICT) exists as a project of the European Union and other associated nations. The trail is long and spans from Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bo ...

to Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

.

The term "Iron Curtain" was only used for the fortified borders in Europe; it was not used for similar borders in Asia between socialist and capitalist states (these were, for a time, dubbed the Bamboo Curtain). The border between North Korea and South Korea is very comparable to the former inner German border, particularly in its degree of militarisation, but it has never conventionally been considered part of any Iron Curtain.

Norway and Finland-Soviet Union

The Soviet Union built a fence along the entire border towardsNorway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

and Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bo ...

. It is located one or a few kilometres from the border, and has automatic alarms detecting if someone climbs over it.

Federal Republic of Germany-German Democratic Republic

The inner German border was marked in rural areas by double fences made of steel mesh (expanded metal) with sharp edges, while near urban areas a high concrete barrier similar to the Berlin Wall was built. The installation of the Wall in 1961 brought an end to a decade during which the divided capital of divided Germany was one of the easiest places to move west across the Iron Curtain.

The barrier was always a short distance inside East German territory to avoid any intrusion into Western territory. The actual borderline was marked by posts and signs and was overlooked by numerous watchtowers set behind the barrier. The strip of land on the West German side of the barrier – between the actual borderline and the barrier – was readily accessible but only at considerable personal risk, because it was patrolled by both East and West German border guards.

Several villages, many historic, were destroyed as they lay too close to the border, for example Erlebach. Shooting incidents were not uncommon, and several hundred civilians and 28 East German border guards were killed between 1948 and 1981 (some may have been victims of "

The inner German border was marked in rural areas by double fences made of steel mesh (expanded metal) with sharp edges, while near urban areas a high concrete barrier similar to the Berlin Wall was built. The installation of the Wall in 1961 brought an end to a decade during which the divided capital of divided Germany was one of the easiest places to move west across the Iron Curtain.

The barrier was always a short distance inside East German territory to avoid any intrusion into Western territory. The actual borderline was marked by posts and signs and was overlooked by numerous watchtowers set behind the barrier. The strip of land on the West German side of the barrier – between the actual borderline and the barrier – was readily accessible but only at considerable personal risk, because it was patrolled by both East and West German border guards.

Several villages, many historic, were destroyed as they lay too close to the border, for example Erlebach. Shooting incidents were not uncommon, and several hundred civilians and 28 East German border guards were killed between 1948 and 1981 (some may have been victims of "friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while e ...

" by their own side).

The Helmstedt–Marienborn border crossing (german: Grenzübergang Helmstedt-Marienborn), named ''Grenzübergangsstelle Marienborn'' (GÜSt) by the German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

(GDR), was the largest and most important border crossing on the Inner German border

The inner German border (german: Innerdeutsche Grenze or ; initially also ) was the border between the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany) and the West Germany, Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) from 1949 to 1990. Not ...

during the division of Germany. Due to its geographical location, allowing for the shortest land route between West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

and West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under m ...

, most transit traffic to and from West Berlin used the Helmstedt-Marienborn crossing. Most travel routes from West Germany to East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

also used this crossing. The border crossing existed from 1945 to 1990 and was situated near the East German village of Marienborn

Marienborn is a village and a former municipality in the Börde district in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Since 1 January 2010, it has been part of the municipality of Sommersdorf. It is about southwest of Haldensleben. The historic pilgrimage centre n ...

at the edge of the Lappwald. The crossing interrupted the Bundesautobahn 2 (A 2) between the junctions ''Helmstedt

Helmstedt (; Eastphalian: ''Helmstidde'') is a town on the eastern edge of the German state of Lower Saxony. It is the capital of the District of Helmstedt. The historic university and Hanseatic city conserves an important monumental heritage o ...

-Ost'' and '' Ostingersleben''.

Austria and Germany-Czechoslovakia

In parts ofCzechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, the border strip became hundreds of meters wide, and an area of increasing restrictions was defined as the border was approached. Only people with the appropriate government permissions were allowed to get close to the border.

Austria-Hungary

The Hungarian outer fence became the first part of the Iron Curtain to be dismantled. After the border fortifications were dismantled, a section was rebuilt for a formal ceremony. On 27 June 1989, the foreign ministers of Austria and Hungary, Alois Mock andGyula Horn

Gyula János Horn (5 July 1932 – 19 June 2013) was a Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1994 to 1998.

Horn is remembered as the last Communist Minister of Foreign Affairs who played a major role in the demolishi ...

, ceremonially cut through the border defences separating their countries.

Yugoslavia-Romania

Yugoslavia-Bulgaria

The Yugoslav-Bulgarian border became closed in 1948 after theTito–Stalin split

The Tito–Stalin split or the Yugoslav–Soviet split was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, respectively, in the years following World W ...

. The area around the border was restructured, with land ownership on both sides no longer legal. Loudspeakers were installed for spreading propaganda and insults. The installations were not as impressive as the one on for example the inner-German border, but they resembled the same system. In the GDR, there was a long time rumor that the border of Bulgaria was easier to cross than the inner German border for escaping the East Bloc.

Greece-Bulgaria

InGreece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

, a highly militarized area called the "Επιτηρούμενη Ζώνη" ("Surveillance Area") was created by the Greek Army along the Greek-Bulgarian border, subject to significant security-related regulations and restrictions. Inhabitants within this wide strip of land were forbidden to drive cars, own land bigger than , and had to travel within the area with a special passport issued by Greek military authorities. Additionally, the Greek state used this area to encapsulate and monitor a non-Greek ethnic minority, the Pomaks

Pomaks ( bg, Помаци, Pomatsi; el, Πομάκοι, Pomáki; tr, Pomaklar) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting northwestern Turkey, Bulgaria and northeastern Greece. The c. 220,000 strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is ...

, a Muslim and Bulgarian-speaking minority which was regarded as hostile to the interests of the Greek state during the Cold War because of its familiarity with their fellow Pomaks living on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

Fall

Following a period of economic and political stagnation under Brezhnev and his immediate successors, the Soviet Union decreased its intervention inEastern Bloc politics

Eastern Bloc politics followed the Red Army's occupation of much of Central and Eastern Europe at the end of World War II and the Soviet Union's installation of Soviet-controlled Marxist–Leninist governments in the region that would be later cal ...

. Mikhail Gorbachev (General Secretary from 1985) decreased adherence to the Brezhnev Doctrine, which held that if socialism were threatened in any state then other socialist governments had an obligation to intervene to preserve it, in favor of the "Sinatra Doctrine

The Sinatra Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy under Mikhail Gorbachev for allowing member states of the Warsaw Pact to determine their own internal affairs. The name jokingly alluded to the song My Way popularized by Frank Sinatra—the ...

". He also initiated the policies of ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

'' (openness) and '' perestroika'' (economic restructuring). A wave of revolutions occurred throughout the Eastern Bloc in 1989.E. Szafarz, "The Legal Framework for Political Cooperation in Europe" in ''The Changing Political Structure of Europe: Aspects of International Law'', Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p.221

Speaking at the Berlin Wall on 12 June 1987, Reagan challenged Gorbachev to go further, saying "General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!" In February 1989, the Hungarian

politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contractio ...

recommended to the government led by Miklós Németh to dismantle the iron curtain. Nemeth first informed Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n chancellor Franz Vranitzky. He then received an informal clearance from Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Comm ...

(who said "there will not be a new 1956

Events

January

* January 1 – The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium ends in Sudan.

* January 8 – Operation Auca: Five U.S. evangelical Christian missionaries, Nate Saint, Roger Youderian, Ed McCully, Jim Elliot and Pete Fleming, are kille ...

") on 3 March 1989, on 2 May of the same year the Hungarian government announced and started in Rajka

Rajka (german: Ragendorf, sk, Rajka, hr, Rakindrof ) is a village in Győr-Moson-Sopron County, Hungary. The village has large Slovak and German minorities.

Etymology

The name comes from the Slavic personal name ''Rajko'', ''Rajka'' (deriv ...

(in the locality known as the "city of three borders", on the border with Austria and Czechoslovakia) the destruction of the Iron Curtain. For public relation Hungary reconstructed 200m of the iron curtain so it could be cut during an official ceremony by Hungarian foreign minister Gyula Horn, and Austrian foreign minister Alois Mock, on 27 June 1989, which had the function of calling all European peoples still under the yoke of the national-communist regimes to freedom. However, the dismantling of the old Hungarian border facilities did not open the borders, nor did the previous strict controls be removed, and the isolation by the Iron Curtain was still intact over its entire length. Despite dismantling the already technically obsolete fence, the Hungarians wanted to prevent the formation of a green border by increasing the security of the border or to technically solve the security of their western border in a different way. After the demolition of the border facilities, the stripes of the heavily armed Hungarian border guards were tightened and there was still a firing order.

In April 1989, the People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

legalised the Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

organisation, which captured 99% of available parliamentary seats in June. These elections, in which anti-communist candidates won a striking victory, inaugurated a series of peaceful anti-communist revolutions in Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and Eastern Europe that eventually culminated in the fall of communism

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

.Padraic Kenney

Padraic Jeremiah Kenney (born March 29, 1963) is an American writer, historian, and educator. He is a professor of history and International Studies at Indiana University. He currently serves as an Associate Dean for Social and Historical Sciences ...

, ''Rebuilding Poland: Workers and Communists, 1945 – 1950'', Cornell University Press, 1996, Google Print, p.4