Introduction to evolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

In the 19th century,

In the 19th century,  Darwin gained extensive experience as he collected and studied the natural history of life forms from distant places. Through his studies, he formulated the idea that each species had developed from ancestors with similar features. In 1838, he described how a process he called natural selection would make this happen.

The size of a population depends on how much and how many resources are able to support it. For the population to remain the same size year after year, there must be an equilibrium or balance between the population size and available resources. Since organisms produce more offspring than their environment can support, not all individuals can survive out of each generation. There must be a competitive struggle for resources that aid in survival. As a result, Darwin realised that it was not chance alone that determined survival. Instead, survival of an organism depends on the differences of each individual organism, or "traits," that aid or hinder survival and reproduction. Well-adapted individuals are likely to leave more offspring than their less well-adapted competitors. Traits that hinder survival and reproduction would ''disappear'' over generations. Traits that help an organism survive and reproduce would ''accumulate'' over generations. Darwin realised that the unequal ability of individuals to survive and reproduce could cause gradual changes in the population and used the term ''natural selection'' to describe this process.

Observations of variations in

Darwin gained extensive experience as he collected and studied the natural history of life forms from distant places. Through his studies, he formulated the idea that each species had developed from ancestors with similar features. In 1838, he described how a process he called natural selection would make this happen.

The size of a population depends on how much and how many resources are able to support it. For the population to remain the same size year after year, there must be an equilibrium or balance between the population size and available resources. Since organisms produce more offspring than their environment can support, not all individuals can survive out of each generation. There must be a competitive struggle for resources that aid in survival. As a result, Darwin realised that it was not chance alone that determined survival. Instead, survival of an organism depends on the differences of each individual organism, or "traits," that aid or hinder survival and reproduction. Well-adapted individuals are likely to leave more offspring than their less well-adapted competitors. Traits that hinder survival and reproduction would ''disappear'' over generations. Traits that help an organism survive and reproduce would ''accumulate'' over generations. Darwin realised that the unequal ability of individuals to survive and reproduce could cause gradual changes in the population and used the term ''natural selection'' to describe this process.

Observations of variations in

A

A

The

The

Strong evidence for evolution comes from the analysis of homologous structures: structures in different species that no longer perform the same task but which share a similar structure. Such is the case of the forelimbs of

Strong evidence for evolution comes from the analysis of homologous structures: structures in different species that no longer perform the same task but which share a similar structure. Such is the case of the forelimbs of  However, anatomical comparisons can be misleading, as not all anatomical similarities indicate a close relationship. Organisms that share similar environments will often develop similar physical features, a process known as ''

However, anatomical comparisons can be misleading, as not all anatomical similarities indicate a close relationship. Organisms that share similar environments will often develop similar physical features, a process known as ''

Every living organism (with the possible exception of

Every living organism (with the possible exception of

"Evolution and the Nature of Science"

/ref> On the other hand, the more distantly related two organisms are, the more differences they will have. For example, brothers are closely related and have very similar DNA, while cousins share a more distant relationship and have far more differences in their DNA. Similarities in DNA are used to determine the relationships between species in much the same manner as they are used to show relationships between individuals. For example, comparing chimpanzees with gorillas and humans shows that there is as much as a 96 percent similarity between the DNA of humans and chimps. Comparisons of DNA indicate that humans and chimpanzees are more closely related to each other than either species is to gorillas. The field of molecular systematics focuses on measuring the similarities in these molecules and using this information to work out how different types of organisms are related through evolution. These comparisons have allowed biologists to build a ''relationship tree'' of the evolution of life on Earth. They have even allowed scientists to unravel the relationships between organisms whose common ancestors lived such a long time ago that no real similarities remain in the appearance of the organisms.

''

''

Given the right circumstances, and enough time, evolution leads to the emergence of new species. Scientists have struggled to find a precise and all-inclusive definition of ''species''. Ernst Mayr defined a species as a population or group of populations whose members have the potential to interbreed naturally with one another to produce viable, fertile offspring. (The members of a species cannot produce viable, fertile offspring with members of ''other'' species). Mayr's definition has gained wide acceptance among biologists, but does not apply to organisms such as

Given the right circumstances, and enough time, evolution leads to the emergence of new species. Scientists have struggled to find a precise and all-inclusive definition of ''species''. Ernst Mayr defined a species as a population or group of populations whose members have the potential to interbreed naturally with one another to produce viable, fertile offspring. (The members of a species cannot produce viable, fertile offspring with members of ''other'' species). Mayr's definition has gained wide acceptance among biologists, but does not apply to organisms such as

A common unit of selection in evolution is the organism. Natural selection occurs when the reproductive success of an individual is improved or reduced by an inherited characteristic, and reproductive success is measured by the number of an individual's surviving offspring. The organism view has been challenged by a variety of biologists as well as philosophers. Evolutionary biologist

A common unit of selection in evolution is the organism. Natural selection occurs when the reproductive success of an individual is improved or reduced by an inherited characteristic, and reproductive success is measured by the number of an individual's surviving offspring. The organism view has been challenged by a variety of biologists as well as philosophers. Evolutionary biologist

In

In biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, evolution is the process of change in all forms of life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

over generations, and evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes such as natural selection, common descent, and speciation that produced the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biolo ...

is the study of how evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

occurs. Biological population

Population is a set of humans or other organisms in a given region or area. Governments conduct a census to quantify the resident population size within a given jurisdiction. The term is also applied to non-human animals, microorganisms, and pl ...

s evolve through genetic changes that correspond to changes in the organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s' observable traits. Genetic changes include mutations

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitosi ...

, which are caused by damage or replication errors in organisms' DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. As the genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations among the same species. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources ...

of a population drifts randomly over generations, natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

gradually leads traits to become more or less common based on the relative reproductive success

Reproductive success is an individual's production of offspring per breeding event or lifetime. This is not limited by the number of offspring produced by one individual, but also the reproductive success of these offspring themselves.

Reproduct ...

of organisms with those traits.

The age of the Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion (astrophysics), accretion, or Internal structure of Earth, core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating ...

is about 4.5 billion years. The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 billion years ago. Evolution does not attempt to explain the origin of life (covered instead by abiogenesis

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life arises from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to living entities on Earth was not a single even ...

), but it does explain how early lifeforms evolved into the complex ecosystem that we see today. Based on the similarities between all present-day organisms, all life on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

is assumed to have originated through common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

from a last universal ancestor from which all known species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

have diverged through the process of evolution.

All individuals have hereditary material in the form of gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s received from their parents, which they pass on to any offspring. Among offspring there are variations of genes due to the introduction of new genes via random changes called mutations or via reshuffling of existing genes during sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

. The offspring differs from the parent in minor random ways. If those differences are helpful, the offspring is more likely to survive and reproduce. This means that more offspring in the next generation will have that helpful difference and individuals will not have equal chances of reproductive

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are al ...

success. In this way, traits that result in organisms being better adapted to their living conditions become more common in descendant populations. These differences accumulate resulting in changes within the population. This process is responsible for the many diverse life forms in the world.

The modern understanding of evolution began with the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''. In addition, Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

's work with plants, between 1856 and 1863, helped to explain the hereditary patterns of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

. Fossil discoveries in palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

, advances in population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and among populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as Adaptation (biology), adaptation, s ...

and a global network of scientific research have provided further details into the mechanisms of evolution. Scientists now have a good understanding of the origin of new species (speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

) and have observed the speciation process in the laboratory and in the wild. Evolution is the principal scientific theory

A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the universe, natural world that can be or that has been reproducibility, repeatedly tested and has corroborating evidence in accordance with the scientific method, using accepted protocol (s ...

that biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

s use to understand life and is used in many disciplines, including medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, conservation biology

Conservation biology is the study of the conservation of nature and of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction and the erosion of biotic interactions. It is an i ...

, anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, forensics

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

, agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

and other social-cultural applications.

Simple overview

The main ideas ofevolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

may be summarised as follows:

* Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

forms reproduce

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. There are two forms of reproduction: asexual and sexual.

In asexual reprod ...

and therefore have a tendency to become more numerous.

* Factors such as predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

and competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indi ...

work against the survival of individuals.

* Each offspring differs from their parent(s) in minor, random ways.

* If these differences are beneficial, the offspring is more likely to survive and reproduce.

* This makes it likely that more offspring in the next generation will have beneficial differences and fewer will have detrimental differences.

* These differences accumulate over generations, resulting in changes within the population.

* Over time, populations can split or branch off into new species.

* These processes, collectively known as evolution, are responsible for the many diverse life forms seen in the world.

Natural selection

In the 19th century,

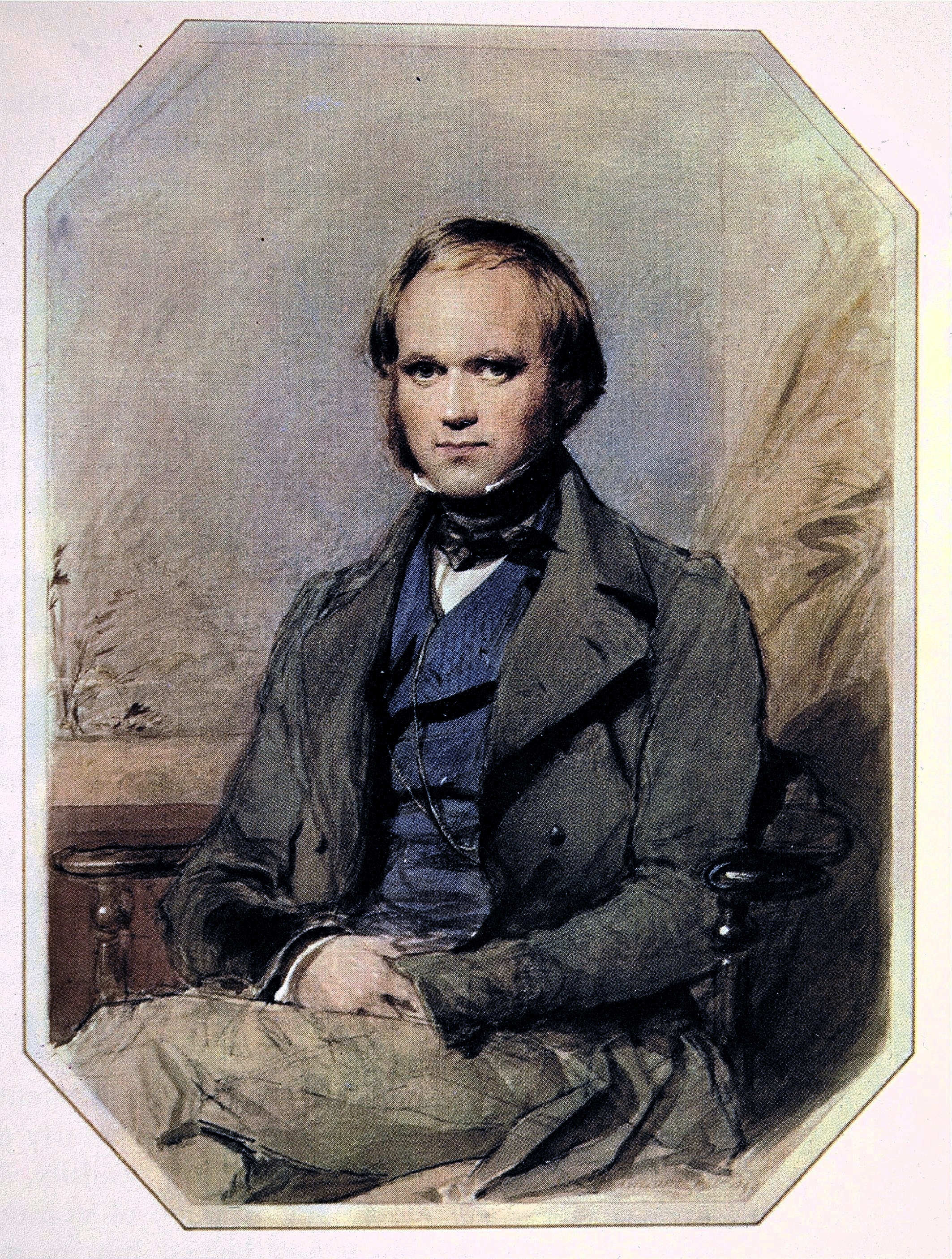

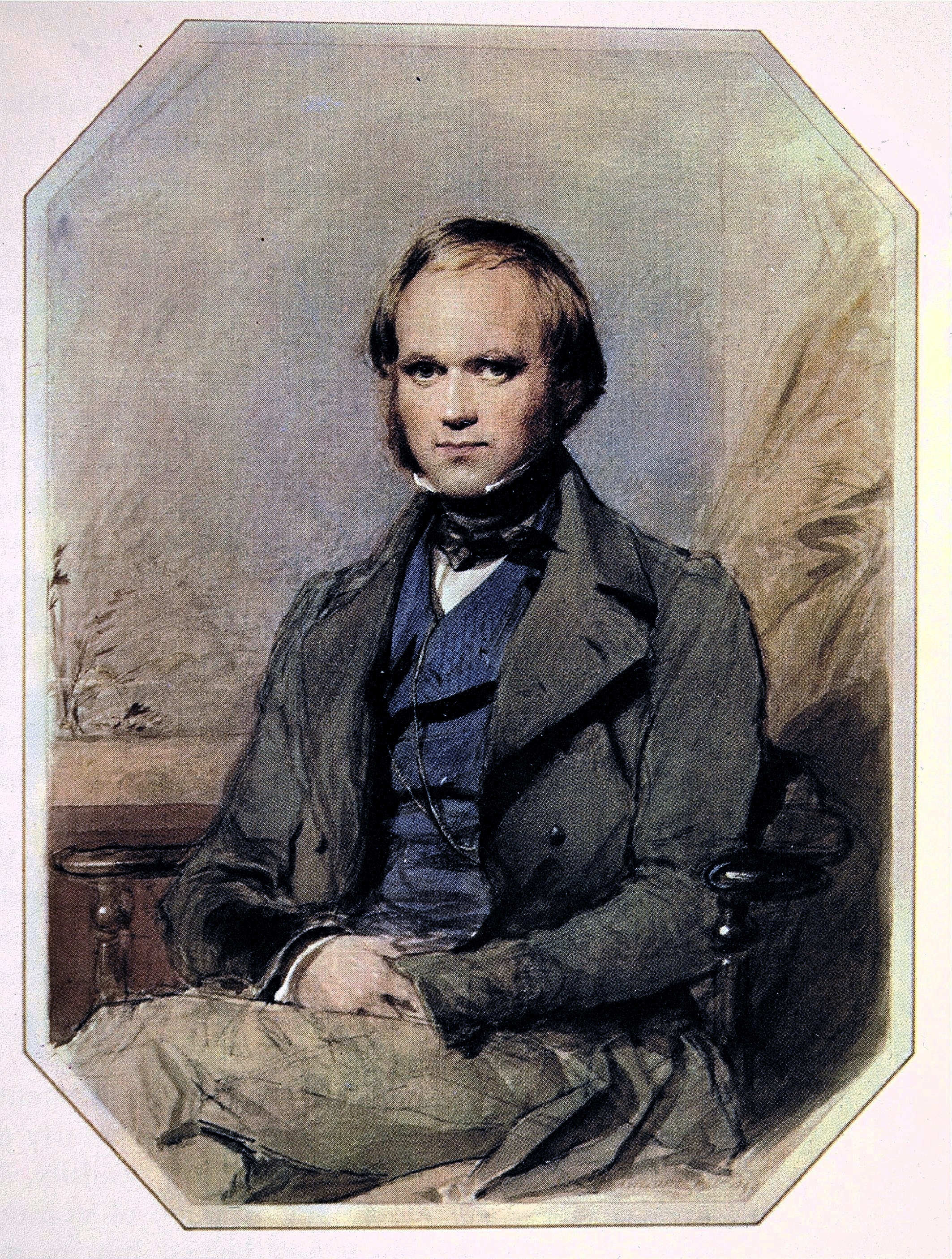

In the 19th century, natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

collections and museums were popular. The European expansion and naval expeditions employed naturalists, while curator

A curator (from , meaning 'to take care') is a manager or overseer. When working with cultural organizations, a curator is typically a "collections curator" or an "exhibitions curator", and has multifaceted tasks dependent on the particular ins ...

s of grand museums showcased preserved and live specimens of the varieties of life. Charles Darwin was an English graduate, educated and trained in the disciplines of natural history. Such natural historians would collect, catalogue, describe and study the vast collections of specimens stored and managed by curators at these museums. Darwin served as a ship's naturalist on board HMS ''Beagle'', assigned to a five-year research expedition around the world. During his voyage, he observed and collected an abundance of organisms, being very interested in the diverse forms of life along the coasts of South America and the neighbouring Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands () are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the equator, west of the mainland of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of sli ...

.

Darwin gained extensive experience as he collected and studied the natural history of life forms from distant places. Through his studies, he formulated the idea that each species had developed from ancestors with similar features. In 1838, he described how a process he called natural selection would make this happen.

The size of a population depends on how much and how many resources are able to support it. For the population to remain the same size year after year, there must be an equilibrium or balance between the population size and available resources. Since organisms produce more offspring than their environment can support, not all individuals can survive out of each generation. There must be a competitive struggle for resources that aid in survival. As a result, Darwin realised that it was not chance alone that determined survival. Instead, survival of an organism depends on the differences of each individual organism, or "traits," that aid or hinder survival and reproduction. Well-adapted individuals are likely to leave more offspring than their less well-adapted competitors. Traits that hinder survival and reproduction would ''disappear'' over generations. Traits that help an organism survive and reproduce would ''accumulate'' over generations. Darwin realised that the unequal ability of individuals to survive and reproduce could cause gradual changes in the population and used the term ''natural selection'' to describe this process.

Observations of variations in

Darwin gained extensive experience as he collected and studied the natural history of life forms from distant places. Through his studies, he formulated the idea that each species had developed from ancestors with similar features. In 1838, he described how a process he called natural selection would make this happen.

The size of a population depends on how much and how many resources are able to support it. For the population to remain the same size year after year, there must be an equilibrium or balance between the population size and available resources. Since organisms produce more offspring than their environment can support, not all individuals can survive out of each generation. There must be a competitive struggle for resources that aid in survival. As a result, Darwin realised that it was not chance alone that determined survival. Instead, survival of an organism depends on the differences of each individual organism, or "traits," that aid or hinder survival and reproduction. Well-adapted individuals are likely to leave more offspring than their less well-adapted competitors. Traits that hinder survival and reproduction would ''disappear'' over generations. Traits that help an organism survive and reproduce would ''accumulate'' over generations. Darwin realised that the unequal ability of individuals to survive and reproduce could cause gradual changes in the population and used the term ''natural selection'' to describe this process.

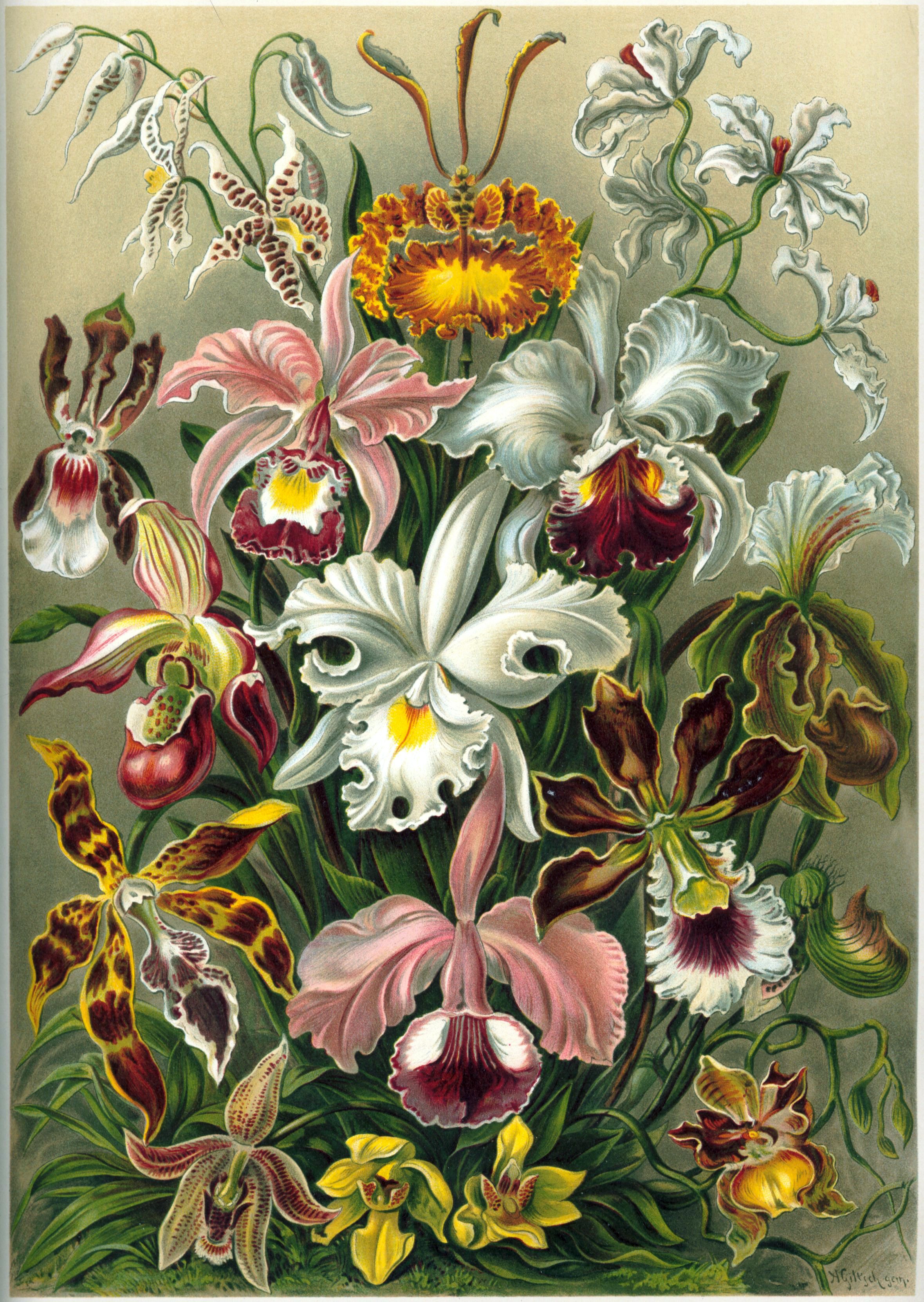

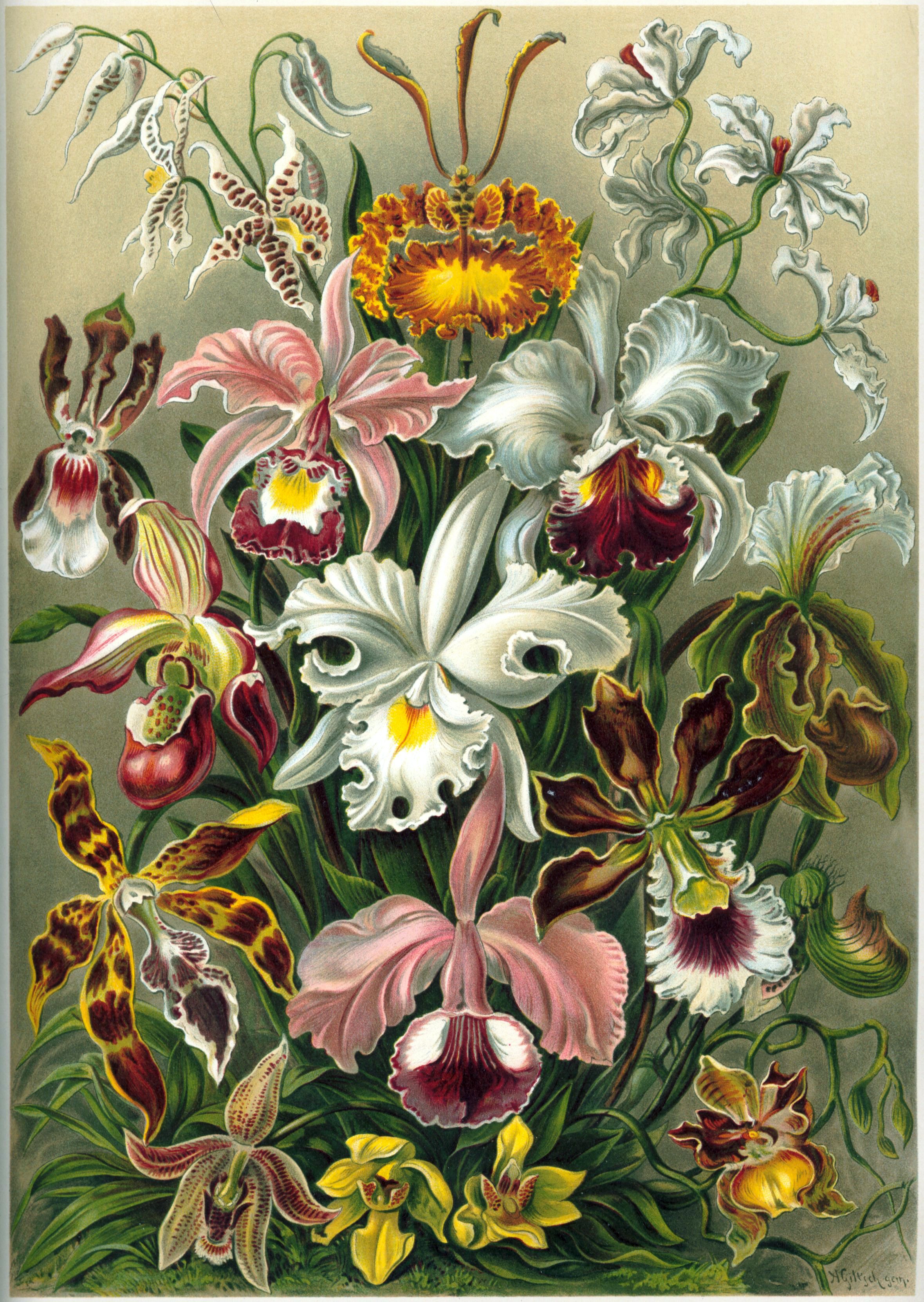

Observations of variations in animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s and plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s formed the basis of the theory of natural selection. For example, Darwin observed that orchids

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant. Orchids are cosmopolitan plants that are found in almost every habitat on Earth ...

and insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s have a close relationship that allows the pollination

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma (botany), stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, for example bees, beetles or bu ...

of the plants. He noted that orchids have a variety of structures that attract insects, so that pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by most types of flowers of seed plants for the purpose of sexual reproduction. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced Gametophyte#Heterospory, microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm ...

from the flower

Flowers, also known as blooms and blossoms, are the reproductive structures of flowering plants ( angiosperms). Typically, they are structured in four circular levels, called whorls, around the end of a stalk. These whorls include: calyx, m ...

s gets stuck to the insects' bodies. In this way, insects transport the pollen from a male to a female orchid. In spite of the elaborate appearance of orchids, these specialised parts are made from the same basic structures that make up other flowers. In his book, ''Fertilisation of Orchids

''Fertilisation of Orchids'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin published on 15 May 1862 under the full explanatory title ''On the Various Contrivances by Which British and Foreign Orchids Are Fertilised by Insects, and On the Good ...

'' (1862), Darwin proposed that the orchid flowers were adapted from pre-existing parts, through natural selection.

Darwin was still researching and experimenting with his ideas on natural selection when he received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

describing a theory very similar to his own. This led to an immediate joint publication of both theories. Both Wallace and Darwin saw the history of life like a family tree

A family tree, also called a genealogy or a pedigree chart, is a chart representing family relationships in a conventional tree structure. More detailed family trees, used in medicine and social work, are known as genograms.

Representations of ...

, with each fork in the tree's limbs being a common ancestor. The tips of the limbs represented modern species and the branches represented the common ancestors that are shared amongst many different species. To explain these relationships, Darwin said that all living things were related, and this meant that all life must be descended from a few forms, or even from a single common ancestor. He called this process ''descent with modification''.

Darwin published his theory of evolution by natural selection in ''On the Origin of Species'' in 1859. His theory means that all life, including human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

ity, is a product of continuing natural processes. The implication that all life on Earth has a common ancestor has been met with objections from some religious groups. Their objections are in contrast to the level of support for the theory by more than 99 percent of those within the scientific community

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "working group, sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional acti ...

today.

Natural selection is commonly equated with ''survival of the fittest'', but this expression originated in Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

's ''Principles of Biology'' in 1864, five years after Charles Darwin published his original works. ''Survival of the fittest'' describes the process of natural selection incorrectly, because natural selection is not only about survival and it is not always the fittest that survives.

Source of variation

Darwin's theory of natural selection laid the groundwork for modern evolutionary theory, and his experiments and observations showed that the organisms in populations varied from each other, that some of these variations were inherited, and that these differences could be acted on by natural selection. However, he could not explain the source of these variations. Like many of his predecessors, Darwin mistakenly thought that heritable traits were a product of use and disuse, and that features acquired during an organism's lifetime could be passed on to its offspring. He looked for examples, such as large ground feedingbird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s getting stronger legs through exercise, and weaker wings from not flying until, like the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

, they could not fly at all., "Effects of the increased Use and Disuse of Parts, as controlled by Natural Selection" This misunderstanding was called the inheritance of acquired characters and was part of the theory of transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

put forward in 1809 by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

. In the late 19th century this theory became known as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

. Darwin produced an unsuccessful theory he called pangenesis to try to explain how acquired characteristics could be inherited. In the 1880s August Weismann

August Friedrich Leopold Weismann (; 17 January 18345 November 1914) was a German evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist. Fellow German Ernst Mayr ranked him as the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Charl ...

's experiments indicated that changes from use and disuse could not be inherited, and Lamarckism gradually fell from favour.

The missing information needed to help explain how new features could pass from a parent to its offspring was provided by the pioneering genetics work of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

. Mendel's experiments with several generations of pea plants demonstrated that inheritance works by separating and reshuffling hereditary information during the formation of sex cells and recombining that information during fertilisation. This is like mixing different hands of playing cards

A playing card is a piece of specially prepared card stock, heavy paper, thin cardboard, plastic-coated paper, cotton-paper blend, or thin plastic that is marked with distinguishing motifs. Often the front (face) and back of each card has a Pap ...

, with an organism getting a random mix of half of the cards from one parent, and half of the cards from the other. Mendel called the information ''factors''; however, they later became known as genes. Genes are the basic units of heredity in living organisms. They contain the information that directs the physical development and behaviour of organisms.

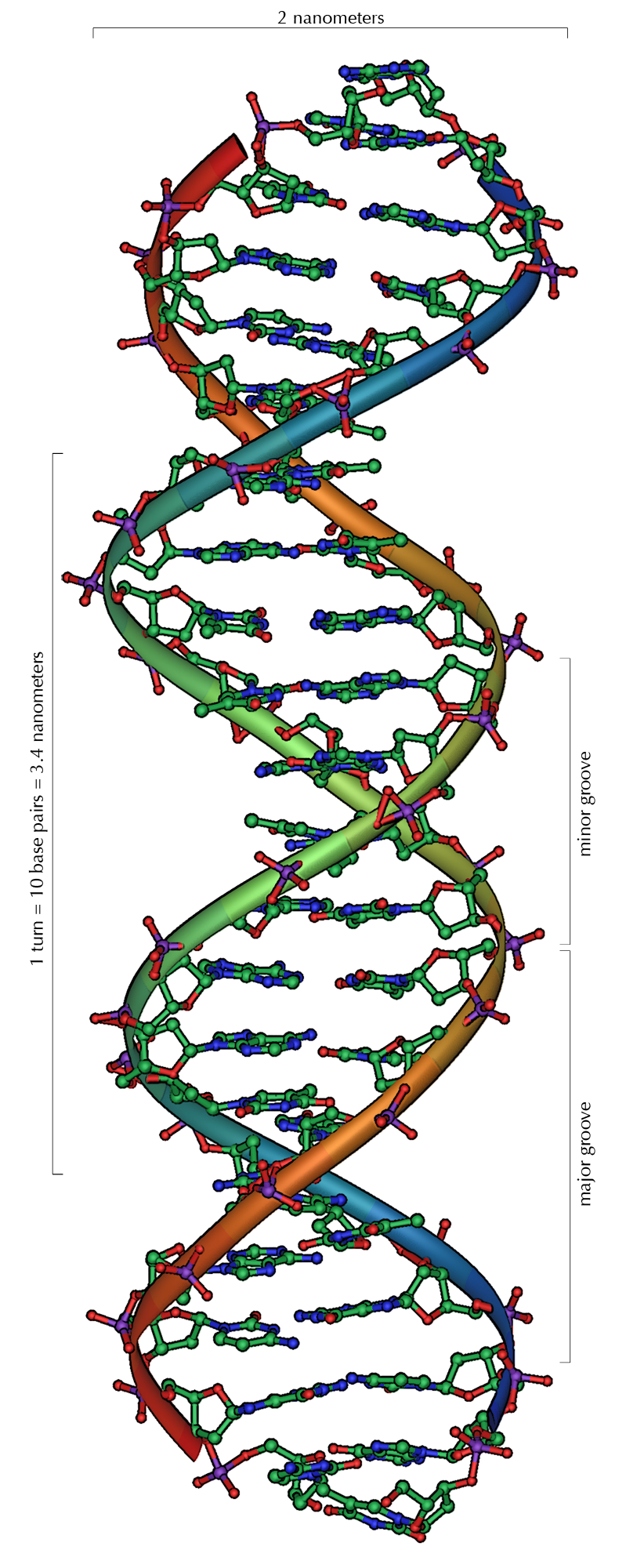

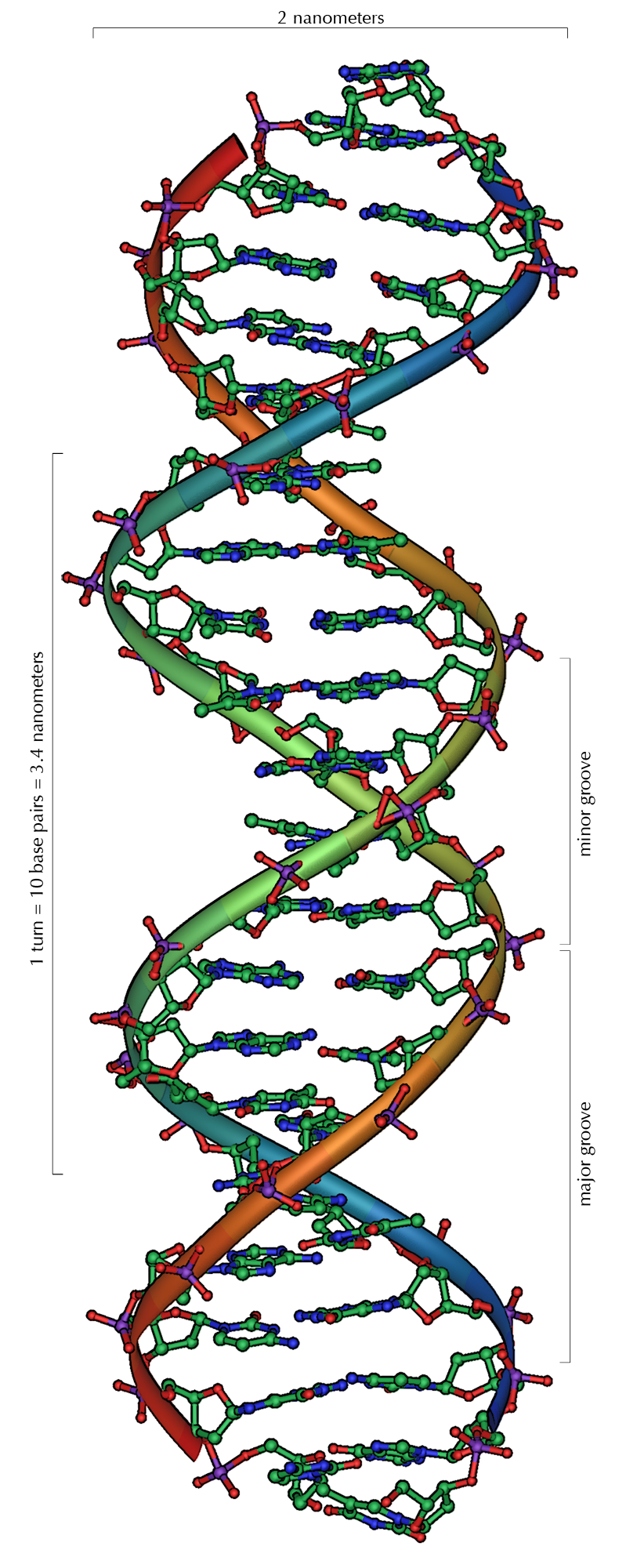

Genes are made of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. DNA is a long molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

made up of individual molecules called nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s. Genetic information is encoded in the sequence of nucleotides, that make up the DNA, just as the sequence of the letters in words carries information on a page. The genes are like short instructions built up of the "letters" of the DNA alphabet. Put together, the entire set of these genes gives enough information to serve as an "instruction manual" of how to build and run an organism. The instructions spelled out by this DNA alphabet can be changed, however, by mutations, and this may alter the instructions carried within the genes. Within the cell, the genes are carried in chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

s, which are packages for carrying the DNA. It is the reshuffling of the chromosomes that results in unique combinations of genes in offspring. Since genes interact with one another during the development of an organism, novel combinations of genes produced by sexual reproduction can increase the genetic variability of the population even without new mutations. The genetic variability of a population can also increase when members of that population interbreed with individuals from a different population causing gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as migration and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic variation, genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent ...

between the populations. This can introduce genes into a population that were not present before.

Evolution is not a random process. Although mutations in DNA are random, natural selection is not a process of chance: the environment determines the probability of reproductive success. Evolution is an inevitable result of imperfectly copying, self-replicating organisms reproducing over billions of years under the selective pressure of the environment. The outcome of evolution is not a perfectly designed organism. The end products of natural selection are organisms that are adapted to their present environments. Natural selection does not involve progress towards an ultimate goal. Evolution does not strive for more advanced, more intelligent, or more sophisticated life forms. For example, flea

Flea, the common name for the order (biology), order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by hematophagy, ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult f ...

s (wingless parasites) are descended from a winged, ancestral scorpionfly, and snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s are lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s that no longer require limbs—although pythons still grow tiny structures that are the remains of their ancestor's hind legs. Organisms are merely the outcome of variations that succeed or fail, dependent upon the environmental conditions at the time.

Rapid environmental changes typically cause extinctions. Of all species that have existed on Earth, 99.9 percent are now extinct. Since life began on Earth, five major mass extinctions have led to large and sudden drops in the variety of species. The most recent, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

, occurred 66 million years ago.

Genetic drift

Genetic drift is a cause of allelic frequency change within populations of a species.Allele

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or Locus (genetics), locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), ...

s are different variations of specific genes. They determine things like hair colour, skin tone, eye colour and blood type

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is based on the presence and absence of antibody, antibodies and Heredity, inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycop ...

; in other words, all the genetic traits that vary between individuals. Genetic drift does not introduce new alleles to a population, but it can reduce variation within a population by removing an allele from the gene pool. Genetic drift is caused by random sampling of alleles. A truly random sample is a sample in which no outside forces affect what is selected. It is like pulling marbles of the same size and weight but of different colours from a brown paper bag. In any offspring, the alleles present are samples of the previous generation's alleles, and chance plays a role in whether an individual survives to reproduce and to pass a sample of their generation onward to the next. The allelic frequency of a population is the ratio of the copies of one specific allele that share the same form compared to the number of all forms of the allele present in the population.

Genetic drift affects smaller populations more than it affects larger populations.

Hardy–Weinberg principle

TheHardy–Weinberg principle

In population genetics, the Hardy–Weinberg principle, also known as the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, model, theorem, or law, states that Allele frequency, allele and genotype frequencies in a population will remain constant from generation ...

states that under certain idealised conditions, including the absence of selection pressures, a large population will have no change in the frequency of alleles as generations pass. A population that satisfies these conditions is said to be in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. In particular, Hardy and Weinberg showed that dominant and recessive alleles do not automatically tend to become more and less frequent respectively, as had been thought previously.

The conditions for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium include that there must be no mutations, immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

, or emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

, all of which can directly change allelic frequencies. Additionally, mating must be totally random, with all males (or females in some cases) being equally desirable mates. This ensures a true random mixing of alleles. A population that is in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium is analogous to a deck of cards; no matter how many times the deck is shuffled, no new cards are added and no old ones are taken away. Cards in the deck represent alleles in a population's gene pool.

In practice, no population can be in perfect Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The population's finite size, combined with natural selection and many other effects, cause the allelic frequencies to change over time.

Population bottleneck

A

A population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as genocide, speciocide, wid ...

occurs when the population of a species is reduced drastically over a short period of time due to external forces. In a true population bottleneck, the reduction does not favour any combination of alleles; it is totally random chance which individuals survive. A bottleneck can reduce or eliminate genetic variation from a population. Further drift events after the bottleneck event can also reduce the population's genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

. The lack of diversity created can make the population at risk to other selective pressures.

A common example of a population bottleneck is the Northern elephant seal. Due to excessive hunting throughout the 19th century, the population of the northern elephant seal was reduced to 30 individuals or less. They have made a full recovery, with the total number of individuals at around 100,000 and growing. The effects of the bottleneck are visible, however. The seals are more likely to have serious problems with disease or genetic disorders, because there is almost no diversity in the population.

Founder effect

founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, us ...

occurs when a small group from one population splits off and forms a new population, often through geographic isolation. This new population's allelic frequency is probably different from the original population's, and will change how common certain alleles are in the populations. The founders of the population will determine the genetic makeup, and potentially the survival, of the new population for generations.

One example of the founder effect is found in the Amish

The Amish (, also or ; ; ), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, church fellowships with Swiss people, Swiss and Alsace, Alsatian origins. As they ...

migration to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

in 1744. Two of the founders of the colony in Pennsylvania carried the recessive allele for Ellis–van Creveld syndrome. Because the Amish tend to be religious isolates, they interbreed, and through generations of this practice the frequency of Ellis–van Creveld syndrome in the Amish people is much higher than the frequency in the general population.

Modern synthesis

The modern evolutionary synthesis is based on the concept that populations of organisms have significant genetic variation caused by mutation and by the recombination of genes during sexual reproduction. It defines evolution as the change in allelic frequencies within a population caused by genetic drift, gene flow between sub populations, and natural selection. Natural selection is emphasised as the most important mechanism of evolution; large changes are the result of the gradual accumulation of small changes over long periods of time. The modern evolutionary synthesis is the outcome of a merger of several different scientific fields to produce a more cohesive understanding of evolutionary theory. In the 1920s,Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

, J.B.S. Haldane and Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright ForMemRS

HonFRSE (December 21, 1889March 3, 1988) was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. He was a founder of population genetics alongside ...

combined Darwin's theory of natural selection with statistical models of Mendelian genetics

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularized ...

, founding the discipline of population genetics. In the 1930s and 1940s, efforts were made to merge population genetics, the observations of field naturalists on the distribution of species and sub species, and analysis of the fossil record into a unified explanatory model. The application of the principles of genetics to naturally occurring populations, by scientists such as Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Grigorievich Dobzhansky (; ; January 25, 1900 – December 18, 1975) was a Russian-born American geneticist and evolutionary biologist. He was a central figure in the field of evolutionary biology for his work in shaping the modern ...

and Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

, advanced the understanding of the processes of evolution. Dobzhansky's 1937 work ''Genetics and the Origin of Species

''Genetics and the Origin of Species'' is a 1937 book by the Ukrainian-American evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky. It is regarded as one of the most important works of Modern synthesis (20th century), modern synthesis and was one of the ...

'' helped bridge the gap between genetics and field biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

by presenting the mathematical work of the population geneticists in a form more useful to field biologists, and by showing that wild populations had much more genetic variability with geographically isolated subspecies and reservoirs of genetic diversity in recessive genes than the models of the early population geneticists had allowed for. Mayr, on the basis of an understanding of genes and direct observations of evolutionary processes from field research, introduced the biological species concept, which defined a species as a group of interbreeding or potentially interbreeding populations that are reproductively isolated from all other populations. Both Dobzhansky and Mayr emphasised the importance of subspecies reproductively isolated by geographical barriers in the emergence of new species. The palaeontologist George Gaylord Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson (June 16, 1902 – October 6, 1984) was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the modern synthesis, contributing '' Tempo ...

helped to incorporate palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

with a statistical analysis of the fossil record that showed a pattern consistent with the branching and non-directional pathway of evolution of organisms predicted by the modern synthesis.

Evidence for evolution

Scientific evidence

Scientific evidence is evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis, although scientists also use evidence in other ways, such as when applying theories to practical problems. "Discussions about empirical ev ...

for evolution comes from many aspects of biology and includes fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s, homologous structures, and molecular similarities between species' DNA.

Fossil record

Research in the field ofpalaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

, the study of fossils, supports the idea that all living organisms are related. Fossils provide evidence that accumulated changes in organisms over long periods of time have led to the diverse forms of life we see today. A fossil itself reveals the organism's structure and the relationships between present and extinct species, allowing palaeontologists to construct a family tree for all of the life forms on Earth.

Modern palaeontology began with the work of Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

. Cuvier noted that, in sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock formed by the cementation (geology), cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or de ...

, each layer contained a specific group of fossils. The deeper layers, which he proposed to be older, contained simpler life forms. He noted that many forms of life from the past are no longer present today. One of Cuvier's successful contributions to the understanding of the fossil record was establishing extinction as a fact. In an attempt to explain extinction, Cuvier proposed the idea of "revolutions" or catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow inc ...

in which he speculated that geological catastrophes had occurred throughout the Earth's history, wiping out large numbers of species. Cuvier's theory of revolutions was later replaced by uniformitarian theories, notably those of James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

who proposed that the Earth's geological changes were gradual and consistent. However, current evidence in the fossil record supports the concept of mass extinctions. As a result, the general idea of catastrophism has re-emerged as a valid hypothesis for at least some of the rapid changes in life forms that appear in the fossil records.

A very large number of fossils have now been discovered and identified. These fossils serve as a chronological record of evolution. The fossil record provides examples of transitional species that demonstrate ancestral links between past and present life forms. One such transitional fossil is ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird'') is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaîos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'', an ancient organism that had the distinct characteristics of a reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

(such as a long, bony tail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

and conical teeth

A tooth (: teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

) yet also had characteristics of birds (such as feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and an exa ...

s and a wishbone). The implication from such a find is that modern reptiles and birds arose from a common ancestor.

Comparative anatomy

The comparison of similarities between organisms of their form or appearance of parts, called theirmorphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

, has long been a way to classify life into closely related groups. This can be done by comparing the structure of adult organisms in different species or by comparing the patterns of how cells grow, divide and even migrate during an organism's development.

Taxonomy

Taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

is the branch of biology that names and classifies all living things. Scientists use morphological and genetic similarities to assist them in categorising life forms based on ancestral relationships. For example, orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

s, gorilla

Gorillas are primarily herbivorous, terrestrial great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or five su ...

s, chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of Hominidae, great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close rel ...

s and human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s all belong to the same taxonomic grouping referred to as a family—in this case the family called Hominidae

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic Family (biology), family of primates that includes eight Neontology#Extant taxa versus extinct taxa, extant species in four Genus, genera: ''Orangutan ...

. These animals are grouped together because of similarities in morphology that come from common ancestry (called '' homology'').

Strong evidence for evolution comes from the analysis of homologous structures: structures in different species that no longer perform the same task but which share a similar structure. Such is the case of the forelimbs of

Strong evidence for evolution comes from the analysis of homologous structures: structures in different species that no longer perform the same task but which share a similar structure. Such is the case of the forelimbs of mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. The forelimbs of a human, cat, whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

, and bat

Bats are flying mammals of the order Chiroptera (). With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their very long spread-out ...

all have strikingly similar bone structures. However, each of these four species' forelimbs performs a different task. The same bones that construct a bat's wings, which are used for flight, also construct a whale's flippers, which are used for swimming. Such a "design" makes little sense if they are unrelated and uniquely constructed for their particular tasks. The theory of evolution explains these homologous structures: all four animals shared a common ancestor, and each has undergone change over many generations. These changes in structure have produced forelimbs adapted for different tasks.

However, anatomical comparisons can be misleading, as not all anatomical similarities indicate a close relationship. Organisms that share similar environments will often develop similar physical features, a process known as ''

However, anatomical comparisons can be misleading, as not all anatomical similarities indicate a close relationship. Organisms that share similar environments will often develop similar physical features, a process known as ''convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

''. Both shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

s and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s have similar body forms, yet are only distantly related—sharks are fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

and dolphins are mammals. Such similarities are a result of both populations being exposed to the same selective pressures. Within both groups, changes that aid swimming have been favoured. Thus, over time, they developed similar appearances (morphology), even though they are not closely related.

Embryology

In some cases, anatomical comparison of structures in theembryo

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sp ...

s of two or more species provides evidence for a shared ancestor that may not be obvious in the adult forms. As the embryo develops, these homologies can be lost to view, and the structures can take on different functions. Part of the basis of classifying the vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

group (which includes humans), is the presence of a tail (extending beyond the anus

In mammals, invertebrates and most fish, the anus (: anuses or ani; from Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is the external body orifice at the ''exit'' end of the digestive tract (bowel), i.e. the opposite end from the mouth. Its function is to facil ...

) and pharyngeal slits. Both structures appear during some stage of embryonic development but are not always obvious in the adult form.

Because of the morphological similarities present in embryos of different species during development, it was once assumed that organisms re-enact their evolutionary history as an embryo. It was thought that human embryos passed through an amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

then a reptilian stage before completing their development as mammals. Such a re-enactment, often called ''recapitulation theory

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an ...

'', is not supported by scientific evidence. What does occur, however, is that the first stages of development are similar in broad groups of organisms. At very early stages, for instance, all vertebrates appear extremely similar, but do not exactly resemble any ancestral species. As development continues, specific features emerge from this basic pattern.

Vestigial structures

Homology includes a unique group of shared structures referred to as '' vestigial structures''. ''Vestigial'' refers to anatomical parts that are of minimal, if any, value to the organism that possesses them. These apparently illogical structures are remnants of organs that played an important role in ancestral forms. Such is the case in whales, which have small vestigial bones that appear to be remnants of the leg bones of their ancestors which walked on land. Humans also have vestigial structures, including the ear muscles, thewisdom teeth

The third molar, commonly called wisdom tooth, is the most posterior of the three molars in each quadrant of the human dentition. The age at which wisdom teeth come through ( erupt) is variable, but this generally occurs between late teens a ...

, the appendix, the tail bone, body hair (including goose bumps

Goose bumps, goosebumps or goose pimples are the bumps on a person's skin at the base of body hairs which may involuntarily develop when a person is Tickling, tickled, cold or experiencing strong emotions such as fear, euphoria or sexual arousa ...

), and the semilunar fold in the corner of the eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

.

Biogeography

Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities o ...

is the study of the geographical distribution of species. Evidence from biogeography, especially from the biogeography of oceanic islands, played a key role in convincing both Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace that species evolved with a branching pattern of common descent. Islands often contain endemic species, species not found anywhere else, but those species are often related to species found on the nearest continent. Furthermore, islands often contain clusters of closely related species that have very different ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s, that is have different ways of making a living in the environment. Such clusters form through a process of adaptive radiation where a single ancestral species colonises an island that has a variety of open ecological niches and then diversifies by evolving into different species adapted to fill those empty niches. Well-studied examples include Darwin's finches

Darwin's finches (also known as the Galápagos finches) are a group of about 18 species of passerine birds. They are well known for being a classic example of adaptive radiation and for their remarkable diversity in beak form and function. They ...

, a group of 13 finch species endemic to the Galápagos Islands, and the Hawaiian honeycreepers, a group of birds that once, before extinctions caused by humans, numbered 60 species filling diverse ecological roles, all descended from a single finch like ancestor that arrived on the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

some 4 million years ago. Another example is the Silversword alliance, a group of perennial plant species, also endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, that inhabit a variety of habitats and come in a variety of shapes and sizes that include trees, shrubs, and ground hugging mats, but which can be hybridised with one another and with certain tarweed species found on the west coast of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

; it appears that one of those tarweeds colonised Hawaii in the past, and gave rise to the entire Silversword alliance.

Molecular biology

Every living organism (with the possible exception of

Every living organism (with the possible exception of RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es) contains molecules of DNA, which carries genetic information. Genes are the pieces of DNA that carry this information, and they influence the properties of an organism. Genes determine an individual's general appearance and to some extent their behaviour. If two organisms are closely related, their DNA will be very similar. NAS 1998"Evolution and the Nature of Science"

/ref> On the other hand, the more distantly related two organisms are, the more differences they will have. For example, brothers are closely related and have very similar DNA, while cousins share a more distant relationship and have far more differences in their DNA. Similarities in DNA are used to determine the relationships between species in much the same manner as they are used to show relationships between individuals. For example, comparing chimpanzees with gorillas and humans shows that there is as much as a 96 percent similarity between the DNA of humans and chimps. Comparisons of DNA indicate that humans and chimpanzees are more closely related to each other than either species is to gorillas. The field of molecular systematics focuses on measuring the similarities in these molecules and using this information to work out how different types of organisms are related through evolution. These comparisons have allowed biologists to build a ''relationship tree'' of the evolution of life on Earth. They have even allowed scientists to unravel the relationships between organisms whose common ancestors lived such a long time ago that no real similarities remain in the appearance of the organisms.

Artificial selection

''

''Artificial selection

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant ...

'' is the controlled breeding of domestic plants and animals. Humans determine which animal or plant will reproduce and which of the offspring will survive; thus, they determine which genes will be passed on to future generations. The process of artificial selection has had a significant impact on the evolution of domestic animals. For example, people have produced different types of dogs by controlled breeding. The differences in size between the Chihuahua and the Great Dane

The Great Dane is a German list of dog breeds, breed of large mastiff-sighthound, which descends from hunting dogs of the Middle Ages used to hunt bears, wild boar, and deer. They were also used as guardian dogs of German nobility. It is one o ...

are the result of artificial selection. Despite their dramatically different physical appearance, they and all other dogs evolved from a few wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

domesticated by humans in what is now China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

less than 15,000 years ago.

Artificial selection has produced a wide variety of plants. In the case of maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

(corn), recent genetic evidence suggests that domestication occurred 10,000 years ago in central Mexico. Prior to domestication, the edible portion of the wild form was small and difficult to collect. Today ''The Maize Genetics Cooperation • Stock Center'' maintains a collection of more than 10,000 genetic variations of maize that have arisen by random mutations and chromosomal variations from the original wild type.

In artificial selection the new breed or variety that emerges is the one with random mutations attractive to humans, while in natural selection the surviving species is the one with random mutations useful to it in its non-human environment. In both natural and artificial selection the variations are a result of random mutations, and the underlying genetic processes are essentially the same. Darwin carefully observed the outcomes of artificial selection in animals and plants to form many of his arguments in support of natural selection. Much of his book ''On the Origin of Species'' was based on these observations of the many varieties of domestic pigeons arising from artificial selection. Darwin proposed that if humans could achieve dramatic changes in domestic animals in short periods, then natural selection, given millions of years, could produce the differences seen in living things today.

Coevolution

Coevolution is a process in which two or more species influence the evolution of each other. All organisms are influenced by life around them; however, in coevolution there is evidence that genetically determined traits in each species directly resulted from the interaction between the two organisms. An extensively documented case of coevolution is the relationship between '' Pseudomyrmex'', a type ofant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

, and the ''acacia

''Acacia'', commonly known as wattles or acacias, is a genus of about of shrubs and trees in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the pea family Fabaceae. Initially, it comprised a group of plant species native to Africa, South America, and Austral ...

'', a plant that the ant uses for food and shelter. The relationship between the two is so intimate that it has led to the evolution of special structures and behaviours in both organisms. The ant defends the acacia against herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat ...

s and clears the forest floor of the seed