Hypsilophodon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Hypsilophodon'' (; meaning "''Hypsilophus''-tooth") is a

The first specimen of ''Hypsilophodon'' was recovered in 1849, when workers dug up the soon-called Mantell-Bowerbank block from an outcrop of the

The first specimen of ''Hypsilophodon'' was recovered in 1849, when workers dug up the soon-called Mantell-Bowerbank block from an outcrop of the  Huxley first announced the new species in 1869 in a lecture; the text of this, published the same year, forms the official naming article, because it contained a sufficient description. The species was named ''Hypsilophodon foxii'', and the

Huxley first announced the new species in 1869 in a lecture; the text of this, published the same year, forms the official naming article, because it contained a sufficient description. The species was named ''Hypsilophodon foxii'', and the  Immediate reception to Huxley's proposal of a new genus, distinct from ''Iguanodon'', was mixed. The issue of distinctiveness was seen as important as more information on the form of ''Iguanodon'' was in demand, and the cranial anatomy in particular was of importance. If the Cowleaze Chine material was a distinct genus, it ceased being useful in this respect. William Boyd Dawkins saw the differences in the two genera (in particular focusing on a differing number of digits) as being as significant as those between '' Equus'' and '' Hipparion'', which is to say that they were quite sufficient for distinction. Harry Seeley gave consideration to the differences in the skulls, and took Huxley's side. Fox, on the other hand, rejected Huxley's proposal of a distinct genus for his material, and subsequently took back his skull and gave it to Owen to study, along with some other fragments.

In attempt to clarify the situation,

Immediate reception to Huxley's proposal of a new genus, distinct from ''Iguanodon'', was mixed. The issue of distinctiveness was seen as important as more information on the form of ''Iguanodon'' was in demand, and the cranial anatomy in particular was of importance. If the Cowleaze Chine material was a distinct genus, it ceased being useful in this respect. William Boyd Dawkins saw the differences in the two genera (in particular focusing on a differing number of digits) as being as significant as those between '' Equus'' and '' Hipparion'', which is to say that they were quite sufficient for distinction. Harry Seeley gave consideration to the differences in the skulls, and took Huxley's side. Fox, on the other hand, rejected Huxley's proposal of a distinct genus for his material, and subsequently took back his skull and gave it to Owen to study, along with some other fragments.

In attempt to clarify the situation,

Later, the number of specimens was increased by

Later, the number of specimens was increased by  Fossils from other locations, especially from the mainland of southern Great Britain,

Fossils from other locations, especially from the mainland of southern Great Britain,

''Hypsilophodon'' was a relatively small dinosaur, though not quite so small as, for example, ''

''Hypsilophodon'' was a relatively small dinosaur, though not quite so small as, for example, ''

Huxley originally assigned ''Hypsilophodon'' to the Iguanodontidae. In 1882

Huxley originally assigned ''Hypsilophodon'' to the Iguanodontidae. In 1882

Due to its small size, ''Hypsilophodon'' fed on low-growing vegetation, in view of the pointed snout most likely preferring high quality plant material, such as young shoots and roots, in the manner of modern

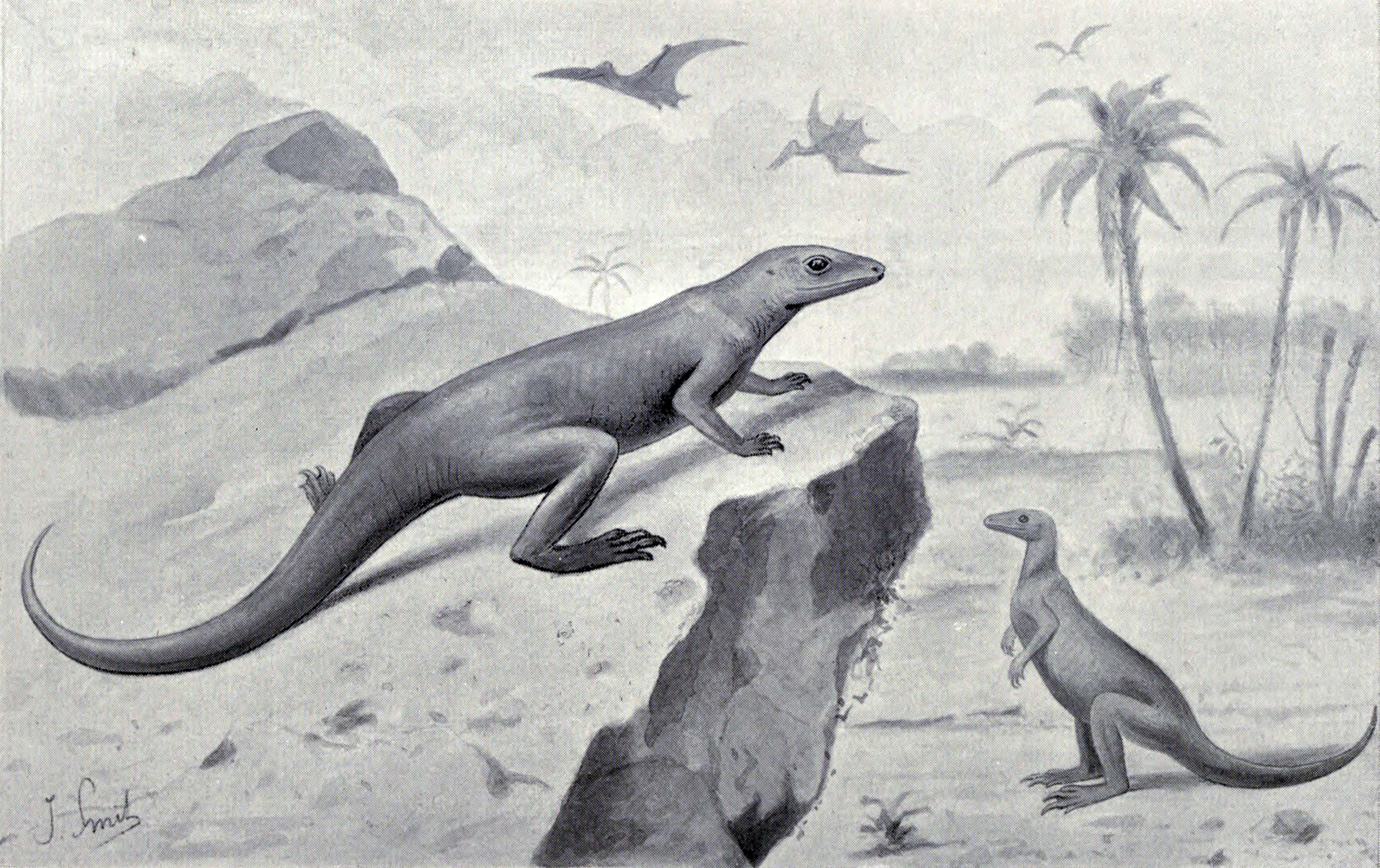

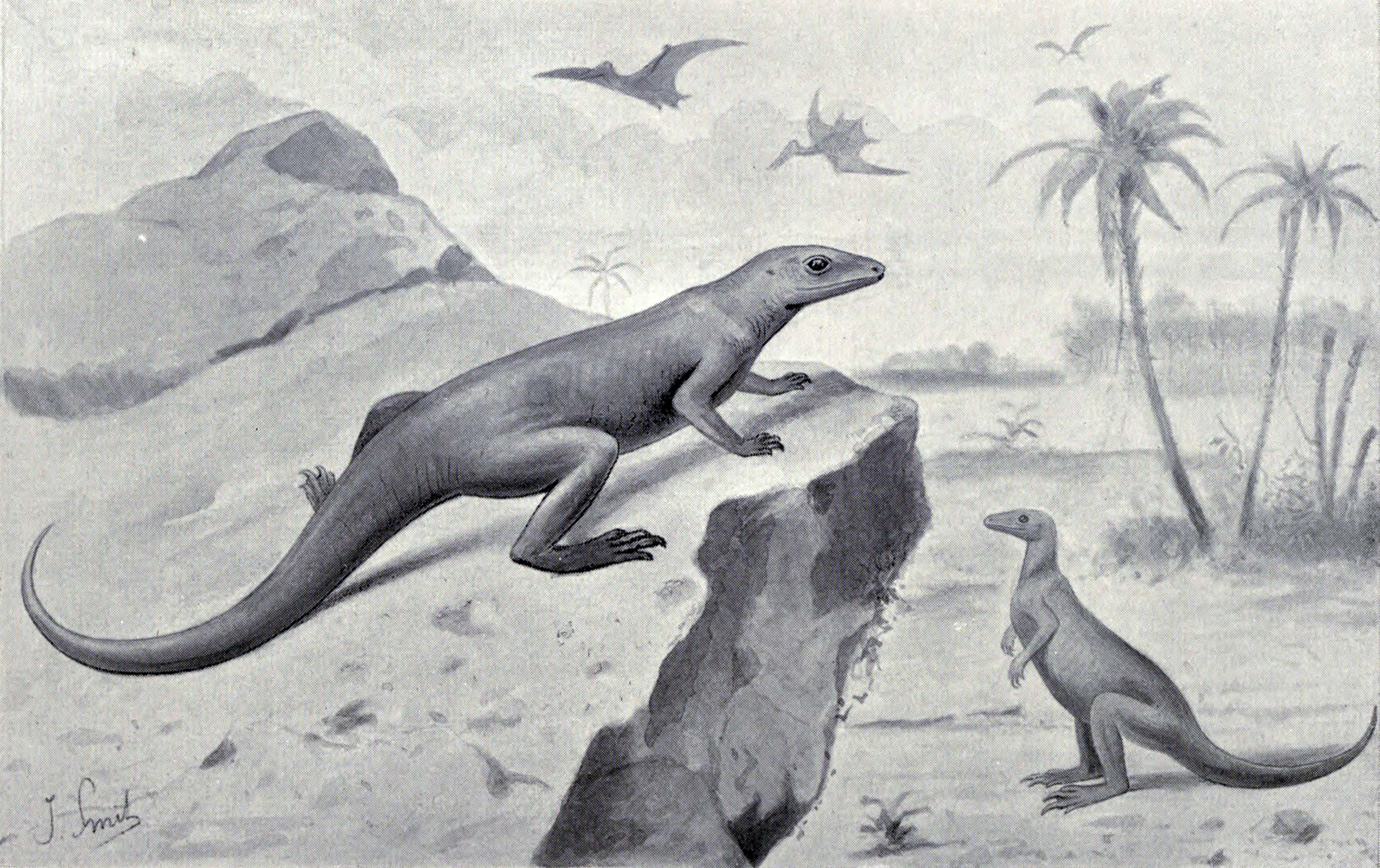

Due to its small size, ''Hypsilophodon'' fed on low-growing vegetation, in view of the pointed snout most likely preferring high quality plant material, such as young shoots and roots, in the manner of modern  Early paleontologists modelled the body of this small, bipedal, herbivorous dinosaur in various ways. In 1882 Hulke suggested that ''Hypsilophodon'' was quadrupedal but also, in view of its grasping hand, able to climb rocks and trees in order to seek shelter. In 1912 this line of thought was further pursued by Austrian paleontologist

Early paleontologists modelled the body of this small, bipedal, herbivorous dinosaur in various ways. In 1882 Hulke suggested that ''Hypsilophodon'' was quadrupedal but also, in view of its grasping hand, able to climb rocks and trees in order to seek shelter. In 1912 this line of thought was further pursued by Austrian paleontologist

neornithischia

Neornithischia ("new ornithischians") is a clade of the dinosaur order Ornithischia. It is the sister group of the Thyreophora within the clade Genasauria. Neornithischians are united by having a thicker layer of asymmetrical enamel on the ins ...

n dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

from the Early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period of England. It has traditionally been considered an early member of the group Ornithopoda

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (), that started out as small, bipedal running grazers and grew in size and numbers until they became one of the most successful groups of herbivores in the Cretaceous worl ...

, but recent research has put this into question.

The first remains of ''Hypsilophodon'' were found in 1849; the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

, ''Hypsilophodon foxii'', was named in 1869. Abundant fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

discoveries were made on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

, giving a good impression of the build of the species. It was a small, agile biped

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

al animal with an herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

or possibly omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nut ...

diet, measuring long and weighing . It had a pointed head equipped with a sharp beak used to bite off plant material, much like modern day parrots.

Older studies have given rise to a number of misconceptions about ''Hypsilophodon'' that it was an armored, arboreal animal and that it could be found in areas outside of Wight. During the past decades, new researches have gradually shown this to be incorrect.

Discovery and history

First specimens and the debate of distinctiveness

The first specimen of ''Hypsilophodon'' was recovered in 1849, when workers dug up the soon-called Mantell-Bowerbank block from an outcrop of the

The first specimen of ''Hypsilophodon'' was recovered in 1849, when workers dug up the soon-called Mantell-Bowerbank block from an outcrop of the Wessex Formation

The Wessex Formation is a fossil-rich English geological formation that dates from the Berriasian to Barremian stages (about 145–125 million years ago) of the Early Cretaceous. It forms part of the Wealden Group and underlies the younger Vect ...

, part of the Wealden Group

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of paralic to continental (freshwater) facies sedimenta ...

, about one hundred yards west of Cowleaze Chine, on the south-west coast of Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

. The larger half of the block (including seventeen vertebrae, parts of ribs and a coracoid, some of the pelvis, and assorted hindleg remains) was given to naturalist James Scott Bowerbank, and the remainder (including eleven caudal vertebrae and most of the rest of hindlegs) to Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

. After his death, Mantell's portion was acquired by the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

; Bowerbank's was acquired later, bringing both halves back together. Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

studied both halves and, in 1855, published a short article on the specimen, considering it to be a young ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning ' iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, ...

'' rather than a new taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

. This was unquestioned until 1867, when Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stori ...

compared the vertebrae and metatarsals of the specimen more closely to those of known ''Iguanodon'', and concluded that it must be a different animal entirely. The next year, he saw a fossil skull discovered by William Fox on exhibition at the Norwich Meeting of the British Associations. Fox, who had also found his fossil in the Cowleaze Chine area, along with several other specimens, considered it to belong to a juvenile ''Iguanodon'', or to represent a new, small species in the genus. Huxley noticed its unique dentition and edentulous premaxilla, reminiscent of but obviously distinct from that of ''Iguanodon''. He concluded this specimen, too, represented a distinct animal from ''Iguanodon''. After losing track of the specimen for some months, Huxley requested Fox grant him permission to study the specimen to a more extensive degree. The request was granted, and Huxley began work on his new species.

Huxley first announced the new species in 1869 in a lecture; the text of this, published the same year, forms the official naming article, because it contained a sufficient description. The species was named ''Hypsilophodon foxii'', and the

Huxley first announced the new species in 1869 in a lecture; the text of this, published the same year, forms the official naming article, because it contained a sufficient description. The species was named ''Hypsilophodon foxii'', and the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

was the Fox skull (which today has the inventory number NHM R197). The next year, Huxley published the expanded full description article. Within the same block of stone as the Fox skull, the centrum of a dorsal vertebra had been preserved. This allowed comparison with the Mantell-Bowerbank block, confirming it to belong to the same species. Further supporting this, Fox had confirmed that the block was found in the same geological bed as his material. As such, Huxley described this specimen in addition to the skull and centrum. It would become the paratype

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype nor a syntype). O ...

; its two pieces are now registered in the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

as specimen NHM 28707, 39560–1. Later in the same year, Huxley classified ''Hypsilophodon'' taxonomically

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

, considering it to belong to the family Iguanodontidae, related to ''Iguanodon'' and '' Hadrosaurus''. There would later be a persistent misunderstanding as to the meaning of the generic name, which is often translated directly from the Greek as "high-ridged tooth". In reality Huxley, analogous to the way the name of the related genus ''Iguanodon'' (" iguana-tooth") had been formed, intended to name the animal after an extant herbivorous lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia altho ...

, choosing for this role '' Hypsilophus'' and combining its name with Greek ὀδών, ''odon'', "tooth". ''Hypsilophodon'' thus means "''Hypsilophus''-tooth". The Greek ὑψίλοφος, ''hypsilophos'', means "high-crested" and refers to the back frill of the lizard, not to the teeth of ''Hypsilophodon'' itself, which are not high-ridged in any case.P.M. Galton, 2009, "Notes on Neocomian (Lower Cretaceous) ornithopod dinosaurs from England - ''Hypsilophodon'', ''Valdosaurus'', "Camptosaurus", "Iguanodon" - and referred specimens from Romania and elsewhere", ''Revue de Paléobiologie'', Genève 28(1): 211-273 The specific name ''foxii'' honours Fox.

Immediate reception to Huxley's proposal of a new genus, distinct from ''Iguanodon'', was mixed. The issue of distinctiveness was seen as important as more information on the form of ''Iguanodon'' was in demand, and the cranial anatomy in particular was of importance. If the Cowleaze Chine material was a distinct genus, it ceased being useful in this respect. William Boyd Dawkins saw the differences in the two genera (in particular focusing on a differing number of digits) as being as significant as those between '' Equus'' and '' Hipparion'', which is to say that they were quite sufficient for distinction. Harry Seeley gave consideration to the differences in the skulls, and took Huxley's side. Fox, on the other hand, rejected Huxley's proposal of a distinct genus for his material, and subsequently took back his skull and gave it to Owen to study, along with some other fragments.

In attempt to clarify the situation,

Immediate reception to Huxley's proposal of a new genus, distinct from ''Iguanodon'', was mixed. The issue of distinctiveness was seen as important as more information on the form of ''Iguanodon'' was in demand, and the cranial anatomy in particular was of importance. If the Cowleaze Chine material was a distinct genus, it ceased being useful in this respect. William Boyd Dawkins saw the differences in the two genera (in particular focusing on a differing number of digits) as being as significant as those between '' Equus'' and '' Hipparion'', which is to say that they were quite sufficient for distinction. Harry Seeley gave consideration to the differences in the skulls, and took Huxley's side. Fox, on the other hand, rejected Huxley's proposal of a distinct genus for his material, and subsequently took back his skull and gave it to Owen to study, along with some other fragments.

In attempt to clarify the situation, John Whitaker Hulke

John Whitaker Hulke FRCS FRS FGS (6 November 1830 – 19 February 1895) was a British surgeon, geologist and fossil collector. He was the son of a physician in Deal, who became a Huxleyite despite being deeply religious.

Hulke became Huxley's ...

returned to the ''Hypsilophodon'' fossil bed on the Isle of Wight to obtain more material, with particular focus on teeth. He remarked that the whole of the skeleton seemed to be represented there, but the fragility of many elements greatly impeded excavation. He published a description of his new specimens in 1873, and based on his examination of the new teeth fossils echoed Fox's sentiments of doubt about the differences from ''Iguanodon''. He commented that Owen was due to argue for the taxon as a distinct species, but within the genus ''Iguanodon''. This came to pass, and Owen compared at length the teeth of known ''Iguanodon'' and those from Fox's specimens. He agreed there were differences, but found them lacking in sufficient distinctiveness to be considered a distinct genus. Regarding Boyd Dawkins' comparison, he acknowledged it, but it did not sway him. As such, he renamed the species ''Iguanodon foxii''.

However, Hulke had, by then, shifted his opinion. He had obtained yet more material from the beds, namely two specimens, one he suspected of being fully grown, which he thought demonstrated the anatomy of the species more clearly than any of the previous ones. Building on Huxley's comments on the Mantell-Bowerbank block, he gave focus to vertebral characters. As a result of his study, he retained that ''Hypsilophodon'' was definitely a relative of ''Iguanodon'', but that it seemed to him too different to be retained in the same genus. He published these findings in a supplementary note, also in 1874. Finally, in 1882 he published a full osteology

Osteology () is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, func ...

of the species, considering it of great importance to properly document the taxon as such a wealth of specimens had been discovered and comparison with American dinosaurs was necessary (Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among ...

had by this point allied the genus to his taxa ''Nanosaurus

''Nanosaurus'' ("small or dwarf lizard") is the name given to a genus of neornithischian dinosaur that lived about 155 to 148 million years ago, during the Late Jurassic-age. Its fossils are known from the Morrison Formation of the south-weste ...

'', ''Laosaurus

''Laosaurus'' (meaning "stone or fossil lizard") is a genus of neornithischian dinosaur. The type species, ''Laosaurus celer'', was first described by O.C. Marsh in 1878 from remains from the Oxfordian-Tithonian-age Upper Jurassic Morrison Forma ...

'', and ''Camptosaurus

''Camptosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of plant-eating, beaked ornithischian dinosaurs of the Late Jurassic period of western North America and possibly also Europe. The name means 'flexible lizard' ( Greek (') meaning 'bent' and (') meaning 'li ...

'' from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

). Fox had by this point died, and no further argument against generic distinctiveness had occurred in the intervening time.

Later research

Reginald Walter Hooley

Reginald Walter Hooley (5 September 1865 – 5 May 1923) was a businessman and amateur paleontologist, collecting on the Isle of Wight. He is probably best remembered for describing the dinosaur ''Iguanodon atherfieldensis'', now ''Mantellisaurus ...

. In 1905, Baron Franz Nopcsa Franz may refer to:

People

* Franz (given name)

* Franz (surname)

Places

* Franz (crater), a lunar crater

* Franz, Ontario, a railway junction and unorganized town in Canada

* Franz Lake, in the state of Washington, United States – see Fran ...

dedicated a study to ''Hypsilophodon'', and in 1936 William Elgin Swinton did the same,Swinton, W.E., 1936, "Notes on the osteology of ''Hypsilophodon'', and on the family Hypsilophodontidae", ''Zoological Society of London, Proceedings'', 1936: 555-578 on the occasion of the mounting of two restored skeletons in the British Museum of Natural History. Most known ''Hypsilophodon'' specimens were discovered between 1849 and 1921 and are in the possession of the Natural History Museum that acquired the collections of Mantell, Fox, Hulke and Hooley. These represent about twenty individual animals. Apart from the holotype and paratype, the most significant specimens are: NHM R5829, the skeleton of a large animal; NHM R5830 and NHM R196/196a, both skeletons of juvenile animals; and NHM R2477, a block with a skull together with two separate vertebral columns. Although this was the largest find, new ones continue to be made.

Modern research of ''Hypsilophodon'' began with the studies of Peter Malcolm Galton

Peter Malcolm Galton (born 14 March 1942 in London) is a British vertebrate paleontologist who has to date written or co-written about 190 papers in scientific journals or chapters in paleontology textbooks, especially on ornithischian and prosaur ...

, starting with his thesis of 1967. He and James Jensen briefly described a left femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates ...

, AMNH

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 i ...

2585, in 1975, and in 1979 formally coined a second species, ''Hypsilophodon wielandi'', for the specimen. The femur was diagnosed with two supposed minor differences from that of ''H. foxii''. The specimen was found in 1900 in the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

, United States, by George Reber Wieland, who the species was named after. Geologically, it comes from the Lakota Sandstone. This species was seen at the time as indicative of a probable late land bridge between North America and Europe, and of the dinosaur fauna of both continents being similar. Spanish Palaeontologist José Ignacio Ruiz-Omeñaca proposed that ''H. wielandi'' was not a species of ''Hypsilophodon'' but instead related to or synonymous with "''Camptosaurus

''Camptosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of plant-eating, beaked ornithischian dinosaurs of the Late Jurassic period of western North America and possibly also Europe. The name means 'flexible lizard' ( Greek (') meaning 'bent' and (') meaning 'li ...

''" ''valdensis'' from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, both species being dryosaurid

Dryosaurids were primitive iguanodonts. They are known from Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous rocks of Africa, Europe, and North America.

Phylogeny

Until recently many dryosaurids have been regarded as dubious ('' Callovosaurus'' and ''Kangn ...

s. Galton refuted this in his contribution to a 2012 book, noting the femurs of the two species to be quite different, and that of ''H. wielandi'' to be unlike those of dryosaurs. He, as well as other studies before and after Ruiz-Omeñaca's proposal, considered ''H. wielandi'' a dubious

Doubt is a mental state in which the mind remains suspended between two or more contradictory propositions, unable to be certain of any of them.

Doubt on an emotional level is indecision between belief and disbelief. It may involve uncertainty ...

basal ornithopod, with ''H. foxii'' the only species in the genus. Galton elaborated on the invalidity of the species in 2009, noting that the two supposed diagnostic characters were variable in both ''H. foxii'' and '' Orodromeus makelai'', making the species dubious. He speculated that it may belong to ''Zephyrosaurus

''Zephyrosaurus'' (meaning "westward wind lizard") is a genus of orodromine ornithischian dinosaur. It is based on a partial skull and postcranial fragments discovered in the Aptian-Albian-age Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Carbon Count ...

'', from a similar time and place, as no femur was known from that taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

.

Fossils from other locations, especially from the mainland of southern Great Britain,

Fossils from other locations, especially from the mainland of southern Great Britain, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

and Spain, have once been referred to ''Hypsilophodon''. However, in 2009 Galton concluded that the specimens from Great Britain proper were either indeterminable or belonged to ''Valdosaurus

''Valdosaurus'' ("Weald Lizard") is a genus of bipedal herbivorous iguanodont ornithopod dinosaur found on the Isle of Wight and elsewhere in England, Spain and possibly also Romania. It lived during the Early Cretaceous.

Discovery and naming

...

'', and that the fossils from the rest of Europe were those of related but different species. This leaves the finds on Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

, off the south coast of England, as the only known authentic ''Hypsilophodon'' fossils. The fossils have been found in the ''Hypsilophodon'' Bed, a one-metre thick marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part ...

layer surfacing in a 1200 metre long strip along the Cowleaze Chine parallel to the southwest coast of Wight, part of the upper Wessex Formation

The Wessex Formation is a fossil-rich English geological formation that dates from the Berriasian to Barremian stages (about 145–125 million years ago) of the Early Cretaceous. It forms part of the Wealden Group and underlies the younger Vect ...

and dating to the late Barremian

The Barremian is an age in the geologic timescale (or a chronostratigraphic stage) between 129.4 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago) and 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma). It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous Epoch (or Lower Cretaceous Series). It is preceded ...

, about 126 million years old. Reports that ''Hypsilophodon'' would be present in the later Vectis Formation

The Vectis Formation is a geological formation on the Isle of Wight and Swanage, England whose strata were formed in the lowermost Aptian, approximately 125 million years ago."Magnetostratigraphy of the Lower Cretaceous Vectis Formation (Wealden ...

, Galton in 2009 considered as unsubstantiated.

Description

Compsognathus

''Compsognathus'' (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''kompsos''/κομψός; "elegant", "refined" or "dainty", and ''gnathos''/γνάθος; "jaw") is a genus of small, bipedalism, bipedal, carnivore, carnivorous theropoda, theropod dinosaur. Members o ...

''. For ''Hypsilophodon'' often a maximum length of is stated. This has its origin in a study of 1974 by Galton, in which he extrapolated a length of based on specimen BMNH R 167, a thigh bone.Galton, P.M., 1974, ''The ornithischian dinosaur ''Hypsilophodon'' from the Wealden of the Isle of Wight''. British Museum (Natural History), Bulletin, Geology, London, 25: 1‑152c However, in 2009, Galton concluded that this femur in fact belonged to ''Valdosaurus'' and downsized ''Hypsilophodon'' to a maximum known length of , the largest specimen being NHM R5829 with a femur length of 202 millimetres. Typical specimens are about long. In 2010, Gregory S. Paul estimated a weight of for an animal in length.

Like most small dinosaurs, ''Hypsilophodon'' was bipedal: it ran on two legs. Its entire body was built for running. Numerous anatomical features aided this, such as: light-weight, minimized skeleton, low, aerodynamic

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

posture, long legs, and stiff tail — immobilized by ossified tendons for balance. In light of this, Galton in 1974 concluded it would have been among the ornithischians best adapted to running. Despite living in the last of the periods in which non-avian dinosaurs walked the earth, the Cretaceous, ''Hypsilophodon'' had a number of seemingly " primitive" features. For example, there were five digits on each hand and four on each foot. With ''Hypsilophodon'' the fifth finger had gained a specialised function: being opposable it could serve to grasp food items.

Cranial anatomy

In an example of primitive anatomy, although it had a beak like mostornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

ns, ''Hypsilophodon'' still had five pointed triangular teeth in the front of the upper jaw, the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

. Most herbivorous dinosaurs had, by the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145& ...

, become sufficiently specialized that the front teeth had been altogether lost (although there is some debate as to whether these teeth may have had a specialized function in ''Hypsilophodon''). More to the back, the upper jaw carried up to eleven teeth in the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

; the lower jaw had up to sixteen teeth. The number was variable, depending on the size of the animal. The teeth to the back were fan-shaped.

The skull of ''Hypsilophodon'' was short and relatively large. The snout was triangular in outline and sharply pointed, ending in an upper beak of which the cutting edge was markedly lower than the maxillary tooth row. The eye socket was very large. A palpebral

An eyelid is a thin fold of skin that covers and protects an eye. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle retracts the eyelid, exposing the cornea to the outside, giving vision. This can be either voluntarily or involuntarily. The human eye ...

with a length equal to half the diameter of the eye socket overshadowed its top section. A sclerotic ring

Sclerotic rings are rings of bone found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates, except for mammals and crocodilians. They can be made up of single bones or multiple segments and take their name from the sclera. They are bel ...

of fifteen small bone plates supported the outer eye surface. The back of the skull was rather high, with a very large and high jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

and quadratojugal The quadratojugal is a skull bone present in many vertebrates, including some living reptiles and amphibians.

Anatomy and function

In animals with a quadratojugal bone, it is typically found connected to the jugal (cheek) bone from the front and ...

closing off a highly positioned small infratemporal fenestra.

Postcranial anatomy

Thevertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

consisted of nine cervical vertebrae, fifteen or sixteen dorsal vertebrae, six of five sacral vertebrae and about forty-eight vertebrae of the tail. Much of the back and the tail was stiffened by long ossified tendons connecting the spines on top of the vertebrae. The processes on the underside of the tail vertebrae, the chevrons, were also connected by ossified tendons, which however were of a different form: they were shorter and split and frayed at one end, with the point of the sharp other end laying within the diverging end of the subsequent tendon. Furthermore, there were several counterdirectional rows of these, resulting in a herring-bone pattern completely immobilising the tail end.

A long-lived misconception concerning the anatomy of ''Hypsilophodon'' has been that it was armoured. This was first suggested by Hulke in 1874, after the find of a bone plate in the neck region.Hulke, J.W., 1874, "Supplemental note on the anatomy of ''Hypsilophodon foxii''", ''Geological Society of London, Quarterly Journal'', 30: 18-23 If so, ''Hypsilophodon'' would have been the only known armoured ornithopod. As Galton pointed out in 2008, the putative armour instead appears to be from the torso, an example of internal intercostal plates associated with the rib cage. It consists of thin mineralized circular plates growing from the back end of the middle rib shaft and overlapping the front edge of the subsequent rib. Such plates are better known from ''Talenkauen

''Talenkauen'' is a genus of basal iguanodont dinosaur from the Campanian or Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous Cerro Fortaleza Formation, formerly known as the Pari Aike Formation of Patagonian Lake Viedma, in the Austral Basin of Sa ...

'' and ''Thescelosaurus

''Thescelosaurus'' ( ; ancient Greek - (''-'') meaning "godlike", "marvellous", or "wondrous" and (') "lizard") was a genus of small neornithischian dinosaur that appeared at the very end of the Late Cretaceous period in North America. It was ...

'', and were probably cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck a ...

in origin.

Phylogeny

Huxley originally assigned ''Hypsilophodon'' to the Iguanodontidae. In 1882

Huxley originally assigned ''Hypsilophodon'' to the Iguanodontidae. In 1882 Louis Dollo

Louis Antoine Marie Joseph Dollo (Lille, 7 December 1857 – Brussels, 19 April 1931) was a Belgian palaeontologist, known for his work on dinosaurs. He also posited that evolution is not reversible, known as Dollo's law. Together with the Austria ...

named a separate Hypsilophodontidae. By the middle of the twentieth century that had become the accepted classification but in the early twenty-first century it became clear through cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analysis that hypsilophodontids formed an unnatural, paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

group of successive off-shoots from throughout Neornithischia

Neornithischia ("new ornithischians") is a clade of the dinosaur order Ornithischia. It is the sister group of the Thyreophora within the clade Genasauria. Neornithischians are united by having a thicker layer of asymmetrical enamel on the ins ...

. ''Hypsilophodon'' in the modern view thus simply is a basal ornithopod. In 2017, Daniel Madzia, Clint Boyd, and Martin Mazuch removed ''Hypsilophodon'' itself from Ornithopoda altogether, placing it as the sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to the Cerapoda, in a more basal position; several other "hypsilophodontids" have undergone similar reclassifications. The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

is reproduced from this study:

Paleobiology

Due to its small size, ''Hypsilophodon'' fed on low-growing vegetation, in view of the pointed snout most likely preferring high quality plant material, such as young shoots and roots, in the manner of modern

Due to its small size, ''Hypsilophodon'' fed on low-growing vegetation, in view of the pointed snout most likely preferring high quality plant material, such as young shoots and roots, in the manner of modern deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the re ...

. The structure of its skull, with the teeth set far back into the jaw, strongly suggests that it had cheeks, an advanced feature that would have facilitated the chewing of food. There were twenty-three to twenty-seven maxillary and dentary teeth with vertical ridges in the animal's upper and lower jaws which, due to the fact that the tooth row of the lower jaw, its teeth curving outwards, fitted within that of the upper jaw, with its teeth curving inwards, appear to have been self-sharpening, the occlusion wearing down the teeth and providing for a simple chewing mechanism. As in almost all dinosaurs and certainly all the ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

ns, the teeth were continuously replaced in an alternate arrangement, with the two replacement waves moving from the back to the front of the jaw. The Zahnreihen-spacing, the average distance in tooth position between teeth of the same eruption stage, was rather low with ''Hyspilophodon'', about 2,3. Such a dentition would have allowed to process relatively tough plants.

Early paleontologists modelled the body of this small, bipedal, herbivorous dinosaur in various ways. In 1882 Hulke suggested that ''Hypsilophodon'' was quadrupedal but also, in view of its grasping hand, able to climb rocks and trees in order to seek shelter. In 1912 this line of thought was further pursued by Austrian paleontologist

Early paleontologists modelled the body of this small, bipedal, herbivorous dinosaur in various ways. In 1882 Hulke suggested that ''Hypsilophodon'' was quadrupedal but also, in view of its grasping hand, able to climb rocks and trees in order to seek shelter. In 1912 this line of thought was further pursued by Austrian paleontologist Othenio Abel

Othenio Lothar Franz Anton Louis Abel (June 20, 1875 – July 4, 1946) was an Austrian paleontologist and evolutionary biologist. Together with Louis Dollo, he was the founder of "paleobiology" and studied the life and environment of fossilized or ...

. Concluding that the first toe of the foot could function as an opposable hallux

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being ''digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being ''plan ...

, Abel stated that ''Hypsilophodon'' was a fully arboreal animal and even that an arboreal lifestyle was primitive for the dinosaurs as a whole. Though this hypothesis was doubted by Nopcsa, it was adopted by the Danish researcher Gerhard Heilmann

Gerhard Heilmann (later sometimes spelt "Heilman") (25 June 1859 – 26 March 1946) was a Danish artist and paleontologist who created artistic depictions of ''Archaeopteryx'', '' Proavis'' and other early bird relatives apart from writing the 19 ...

who in 1916 proposed that a quadrupedal ''Hypsilophodon'' lived like the modern tree-kangaroo '' Dendrolagus''. In 1926 Heilmann had again changed his mind, denying that the first toe was opposable because the first metatarsal was firmly connected to the second, but in 1927 Abel refused to accept this. In this he was in 1936 supported by Swinton who claimed that even a forward pointing first metatarsal might carry a movable toe. As Swinton was a very influential populariser of dinosaurs, this remained the accepted view for over three decades, most books typically illustrating ''Hypsilophodon'' sitting on a tree branch. However, Peter M. Galton in 1969 performed a more accurate analysis of the musculo-skeletal structure, showing that the body posture was horizontal. In 1971 Galton in detail refuted Abel's arguments, showing that the first toe had been incorrectly reconstructed and that neither the curvature of the claws, nor the level of mobility of the shoulder girdle or the tail could be seen as adaptations for climbing, concluding that ''Hypsilophodon'' was a bipedal running form.Galton, P.M., 1971, "The mode of life of ''Hypsilophodon'', the supposedly arboreal ornithopod dinosaur", ''Lethaia'', 4: 453-465 This convinced the paleontological community that ''Hypsilophodon'' remained firmly on the ground.

The level of parental care in this dinosaur has not been defined, nests not having been found, although neatly arranged nests are known from related species, suggesting that some care was taken before hatching. The ''Hypsilophodon'' fossils were probably accumulated in a single mass mortality event, so it has been considered likely that the animals moved in large groups. For these reasons, the hypsilophodonts, particularly ''Hypsilophodon'', have often been referred to as the "deer of the Mesozoic". Some indications about the reproductive habits are provided by the possibility of sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

: Galton considered it likely that exemplars with five instead of six sacral vertebrae — with some specimens the vertebra that should normally count as the first of the sacrum has a rib not touching the pelvis — represented female individuals.

References

Bibliography

* {{Taxonbar, from=Q131086 Ornithischian genera Barremian life Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of Europe Cretaceous England Fossils of England Fossil taxa described in 1869 Taxa named by Thomas Henry Huxley