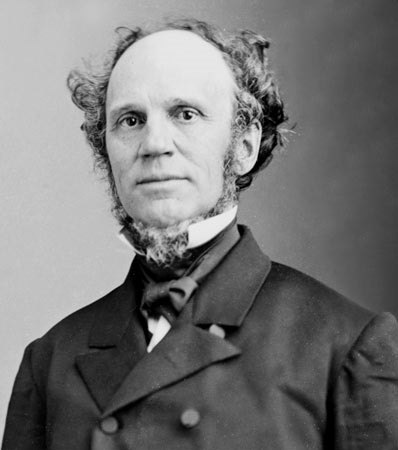

Horatio Seymour on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as

Norwich University, 1819–1911

' Seymour read for the law in the offices of Greene Bronson and

In 1862, the sitting governor, Republican Edwin D. Morgan, announced that he would not run for an additional term. Recognizing the symbolic importance of a victory in the Empire State, the Democratic Party nominated Seymour as the strongest candidate available. Though Seymour accepted the nomination with reluctance, he threw himself into the election, campaigning across the state in the hope that a Democratic victory would restrain the actions of the

In 1862, the sitting governor, Republican Edwin D. Morgan, announced that he would not run for an additional term. Recognizing the symbolic importance of a victory in the Empire State, the Democratic Party nominated Seymour as the strongest candidate available. Though Seymour accepted the nomination with reluctance, he threw himself into the election, campaigning across the state in the hope that a Democratic victory would restrain the actions of the

Seymour continued as a prominent figure in national Democratic politics both during and immediately after his second term as governor. In 1864, he served as permanent chairman at the Democratic National Convention, where the opposition of many delegates to the two frontrunners, General

Seymour continued as a prominent figure in national Democratic politics both during and immediately after his second term as governor. In 1864, he served as permanent chairman at the Democratic National Convention, where the opposition of many delegates to the two frontrunners, General

With the nomination forced upon him, Seymour committed himself to the campaign. He faced considerable challenges; his opponent, General

With the nomination forced upon him, Seymour committed himself to the campaign. He faced considerable challenges; his opponent, General

There is a memorial to Seymour at the

There is a memorial to Seymour at the

excerpt

* *

online edition

* , a standard scholarly biography. * Murdock, Eugene C. "Horatio Seymour and the 1863 draft." ''Civil War History'' 11.2 (1965): 117-141

excerpt

* , thin *

online

Mr. Lincoln and New York: Horatio Seymour

*First Edition 1862 Report o

Winning New York Governor's Race.

''Speeches of Hon. Horatio Seymour : at the conventions held at Albany, January 31, 1861 and September 10, 1862''

Political Graveyard , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Seymour, Horatio 1810 births 1886 deaths American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law American Protestants Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees Democratic Party governors of New York (state) Governors of New York (state) Mayors of Utica, New York New York (state) lawyers Norwich University alumni People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Speakers of the New York State Assembly Democratic Party members of the New York State Assembly Union (American Civil War) political leaders Union (American Civil War) state governors Candidates in the 1868 United States presidential election Seymour family (U.S.) 19th-century American lawyers 19th-century American businesspeople Burials at Forest Hill Cemetery (Utica, New York)

Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor h ...

from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential election

The 1868 United States presidential election was the 21st quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1868. In the first election of the Reconstruction Era, Republican nominee Ulysses S. Grant defeated Horatio Seymour of the ...

, losing to Republican Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

.

Born in Pompey, New York

Pompey is a town in the southeast part of Onondaga County, New York. The population was 7,080 at the time of the 2010 census. The town was named after the Roman general and political leader Pompey by a late 18th-century clerk interested in the Cla ...

, Seymour was admitted to the New York bar in 1832. He primarily focused on managing his family's business interests. After serving as a military secretary to Governor William L. Marcy

William Learned Marcy (December 12, 1786July 4, 1857) was an American lawyer, politician, and judge who served as U.S. Senator, Governor of New York, U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of State. In the latter office, he negotiated the Ga ...

, Seymour won election to the New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Ass ...

. He was elected that body's speaker in 1845 and aligned with Marcy's "Softshell Hunker" faction. Seymour was nominated for governor in 1850 but narrowly lost to the Whig candidate, Washington Hunt

Washington Hunt (August 5, 1811 – February 2, 1867) was an American lawyer and politician.

Life and career

Hunt was born in Windham, New York. He moved to Lockport, New York in 1828 to study law, was admitted to the bar in 1834, and opene ...

. He defeated Hunt in the 1852 gubernatorial election, and spent much of his tenure trying to reunify the fractured Democratic Party, losing his 1854 re-election campaign in part due to this disunity.

Despite this defeat, Seymour emerged as a prominent national figure within the party. As several Southern states threatened secession, Seymour supported the Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator J ...

as a way to avoid civil war. He supported the Union war effort during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

but criticized President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's leadership. He won election to another term as governor in 1862 and continued to oppose many of Lincoln's policies. Several delegates at the 1864 Democratic National Convention

The 1864 Democratic National Convention was held at The Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois.

The Convention nominated Major General George B. McClellan from New Jersey for president, and Representative George H. Pendleton of Ohio for vice presid ...

hoped to nominate Seymour for president, but Seymour declined to seek the nomination. Beset by various issues, he narrowly lost re-election in 1864. After the war, Seymour supported President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

's Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policies.

As the 1868 Democratic National Convention

The 1868 Democratic National Convention was held at Tammany Hall in New York City between July 4, and July 9, 1868. The first Democratic convention after the conclusion of the American Civil War, the convention was notable for the return of Democr ...

opened, there was no clear front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, but Seymour remained widely popular. Serving as the chairman of the convention, as he had in 1864, Seymour refused to seek the nomination for himself. After twenty-two indecisive ballots, the convention nominated Seymour, who finally relented on his opposition to running for president. Seymour faced General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, the widely popular Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

nominee, in the 1868 election. Grant won a strong majority of the electoral vote, though his margin in the popular vote was not as overwhelming. Seymour never again sought public office but remained active in politics and supported Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's 1884 campaign for president.

Early life and education

Seymour was born in Pompey Hill,Onondaga County

Onondaga County ( ) is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 476,516. The county seat is Syracuse.

Onondaga County is the core of the Syracuse, NY MSA.

History

The name ''Onondaga'' derives from ...

, New York. His father was Henry Seymour, a merchant and politician; his mother, Mary Ledyard Forman (1785–1859), of Matawan, New Jersey, was the daughter of General Jonathan Forman and Mary Ledyard. He was one of six children, and his sister Julia Catherine became the wife of Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

. At the age of 10 he moved with the rest of his family to Utica, where he attended a number of local schools, including Geneva College (later Hobart College). In the autumn of 1824 he was sent to the American Literary, Scientific & Military Academy (Norwich University). Upon his return to Utica after graduating in 1828,Norwich University, 1819–1911

' Seymour read for the law in the offices of Greene Bronson and

Samuel Beardsley

Samuel Beardsley (February 6, 1790 – May 6, 1860) was an American attorney, judge and legislator from New York. During his career he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York Attorney General, United States ...

. Though admitted to the bar in 1832, he did not enjoy work as an attorney and was primarily preoccupied with politics and managing his family's business interests.Stewart Mitchell, ''Horatio Seymour of New York'' (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938). He married Mary Bleecker in 1835.

Political career

Entry into politics

Seymour's first role in politics came in 1833, when he was named military secretary to the state's newly elected Democratic governor,William L. Marcy

William Learned Marcy (December 12, 1786July 4, 1857) was an American lawyer, politician, and judge who served as U.S. Senator, Governor of New York, U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of State. In the latter office, he negotiated the Ga ...

with the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

. The six years in that position gave Seymour an invaluable education in the politics of the state, and established a firm friendship between the two men. In 1839 he returned to Utica to take over the management of his family's estate in the aftermath of his father's suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

two years earlier, investing profitably in real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

, banks

A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital markets.

Becaus ...

, mines, railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

, and other ventures. In 1841 he won election to the New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Ass ...

, and he served simultaneously as mayor of Utica from 1842 to 1843. He won election to the Assembly again in 1843 to 1844, and thanks in part to massive turnover in the ranks of the Democratic caucus he was elected speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

in 1845.

When, in the late 1840s, the New York Democratic Party split between the two factions of Hunkers and Barnburners, Seymour was among those identified with the more conservative Hunker faction, led by Marcy and Senator Daniel S. Dickinson

Daniel Stevens Dickinson (September 11, 1800April 12, 1866) was an American politician and lawyer, most notable as a United States senator from 1844 to 1851.

Biography

Born in Goshen, Connecticut, he moved with his parents to Guilford, Chenan ...

. After this split led to disaster in the election of 1848, when the division between the Hunkers, who supported Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

, and the Barnburners, who supported their leader, former President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, Seymour became identified with Marcy's faction within the Hunkers, the so-called "Softshell Hunkers," who hoped to reunite with the Barnburners so as to be able to bring back Democratic dominance within the state.

First term as governor

In 1850, Seymour was the gubernatorial candidate of the reunited Democratic Party, but he narrowly lost to the Whig candidate,Washington Hunt

Washington Hunt (August 5, 1811 – February 2, 1867) was an American lawyer and politician.

Life and career

Hunt was born in Windham, New York. He moved to Lockport, New York in 1828 to study law, was admitted to the bar in 1834, and opene ...

. Seymour and the Softs supported the candidacy of their leader, Marcy, for the presidency in 1852, but when he was defeated they enthusiastically campaigned for Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

in 1852. That year proved a good one for the Softs, as Seymour, again supported by a unified Democratic Party, narrowly defeated Hunt in a gubernatorial rematch, while Pierce, overwhelmingly elected president, appointed Marcy as his Secretary of State.

Seymour's first term as governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor h ...

proved turbulent. He won approval of a measure to finance the enlargement of the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing ...

via a $10.5 million loan in a special election in February 1854. But much of his tenure was plagued by factional chaos within the state Democratic Party. The Pierce administration's use of the patronage power alienated the Hards, who determined to run their own gubernatorial candidate against Seymour in 1854. Furthermore, the administration's support of the unpopular Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

, with which Seymour was associated indirectly through his friendship with Marcy, cost him many votes. Whigs controlling the state legislature also sought to injure him further politically by responding to his call for action on the problem of alcohol abuse

Alcohol abuse encompasses a spectrum of unhealthy alcohol drinking behaviors, ranging from binge drinking to alcohol dependence, in extreme cases resulting in health problems for individuals and large scale social problems such as alcohol-rela ...

with a bill establishing a statewide prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

, which Seymour vetoed as unconstitutional. Yet for all his troubles Seymour's prospects for reelection looked promising, as the divisions of the Democrats' opponents between the regular Whig candidate, Myron H. Clark, and the Know-Nothing Daniel Ullman appeared to be more dangerous to the Democrats' opponents than the candidacy of the Hard Greene C. Bronson

Greene Carrier Bronson (November 17, 1789 in Simsbury, Hartford County, Connecticut – September 3, 1863 in Saratoga, New York) was an American lawyer and politician from New York.

Life

He was the son of Oliver Bronson (1746–1815, a music tea ...

looked to Democratic unity. In the end, however, the anti-Democratic tide was too strong, and in the four-way race Clark, who received only one-third of the vote, defeated Seymour by 309 votes.

Interlude

Despite his defeat, as a former governor of the largest state of the Union, Seymour emerged as a prominent figure in party politics at the national level. In 1856, he was considered a possible compromise presidential candidate in the event of a deadlock betweenFranklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

and James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

until he wrote a letter definitively ruling himself out. In 1860, some considered Seymour a compromise candidate for the Democratic nomination at the reconvening convention in Baltimore. Seymour wrote a letter to the editor of his local newspaper declaring unreservedly that he was not candidate for either president or vice president. Seymour supported the candidacy of Stephen A. Douglas for the presidency in both 1856 and 1860. In 1861, he accepted nomination as the Democratic candidate for the United States Senate, which was largely an empty honor as the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

majorities in the state legislature rendered a Republican victory a foregone conclusion.

In the secession crisis

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

following Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's election in 1860

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The discovery of a hypothetical planet Vulcan is announced at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris, France.

* January 10 – The Pemberton Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts ...

, Seymour strongly endorsed the proposed Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator J ...

. After the start of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Seymour took a cautious middle position within his party, supporting the war effort but criticizing Lincoln's conduct of the war. Seymour was especially critical of Lincoln's wartime centralization of power and restrictions on civil liberties, as well as his support for emancipation.

Second term as governor

In 1862, the sitting governor, Republican Edwin D. Morgan, announced that he would not run for an additional term. Recognizing the symbolic importance of a victory in the Empire State, the Democratic Party nominated Seymour as the strongest candidate available. Though Seymour accepted the nomination with reluctance, he threw himself into the election, campaigning across the state in the hope that a Democratic victory would restrain the actions of the

In 1862, the sitting governor, Republican Edwin D. Morgan, announced that he would not run for an additional term. Recognizing the symbolic importance of a victory in the Empire State, the Democratic Party nominated Seymour as the strongest candidate available. Though Seymour accepted the nomination with reluctance, he threw himself into the election, campaigning across the state in the hope that a Democratic victory would restrain the actions of the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

in Washington. He won a close race against the Republican candidate James S. Wadsworth, one of a series of victories by the Democratic ticket in the state that year.

Seymour's second term proved to be even more tumultuous than his first one. As governor of the largest state in the Union from 1863 to 1864, Seymour was one of the most prominent Democratic opponents of the President. He opposed the Lincoln administration's institution of the military draft in 1863 on constitutional grounds, an act which led many to question his support for the war. He also opposed a bill giving votes to the soldiers on legal grounds, vetoing the bill when it reached his desk. While not opposed to the goal he preferred to establish voting provisions through a constitutional amendment that was working its way simultaneously through the state legislature; nonetheless, his veto was portrayed by opponents as hostility to the soldiers. His decision to pay the state's foreign creditors using gold rather than greenbacks alienated "easy money" supporters, while his veto of a bill granting traction rights on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

in Manhattan earned him the opposition of Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

. Finally, his efforts to conciliate the rioters during the New York Draft Riots

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week, were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of white working-cla ...

of July 1863 was used against him by the Republicans, who accused him of treason and support for the Confederacy.

The growing accumulation of problems steadily eroded Seymour's position as governor. In what was regarded as a rebuke of his policies, Republicans swept the 1863 state midterm elections, winning all of the major offices and taking control of the State Assembly. In the state elections the following year, Seymour himself was defeated for reelection in a close race by Republican Reuben Fenton.

Prominent Democrat

Seymour continued as a prominent figure in national Democratic politics both during and immediately after his second term as governor. In 1864, he served as permanent chairman at the Democratic National Convention, where the opposition of many delegates to the two frontrunners, General

Seymour continued as a prominent figure in national Democratic politics both during and immediately after his second term as governor. In 1864, he served as permanent chairman at the Democratic National Convention, where the opposition of many delegates to the two frontrunners, General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, a War Democrat

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the Con ...

, and Thomas H. Seymour (no relation to Horatio), a Copperhead, led many to seek out Seymour as a compromise candidate. He refused to be nominated, however, with the nomination ultimately going to McClellan. In the aftermath of the war Seymour joined other Democrats in supporting President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

's Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policies, and was a strong opponent of Radical Reconstruction

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, with its emphasis on guaranteeing civil and political rights for freed slaves.

1868 Presidential election

Nomination

As the 1868 presidential election approached, there was no clear candidate for the Democratic nomination. Of the numerous candidates in contention,George H. Pendleton

George Hunt Pendleton (July 19, 1825November 24, 1889) was an American politician and lawyer. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1864.

After study ...

, who had run as the Democratic vice-presidential nominee in 1864, enjoyed considerable support but alienated the fiscal conservatives in the party with his plan to pay off federal debt using greenbacks. When Seymour was approached about running for the nomination, he demurred again, preferring that either Indiana Senator Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until his ...

or U.S. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

receive the nomination instead.

At the convention, Seymour once again served as permanent chairman. Balloting began on June 7; on the fourth ballot, the chairman of the North Carolina delegation cast his state's votes for Seymour, whereupon the former governor again restated his refusal to accept the nomination. Two days later, as the twenty-second ballot was being taken, it appeared that Hendricks was in the process of winning the nomination until the leader of the Ohio delegation suddenly switched his delegation's votes to Seymour. Though Seymour reiterated his unwillingness to be the nominee, the delegations revised their votes and gave the nomination to him unanimously.

Campaign

With the nomination forced upon him, Seymour committed himself to the campaign. He faced considerable challenges; his opponent, General

With the nomination forced upon him, Seymour committed himself to the campaign. He faced considerable challenges; his opponent, General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, enjoyed the support of a unified Republican party and most of the nation's press. While he generally adhered to the tradition that presidential nominees did not actively campaign, Seymour did undertake a tour of the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic states in mid-October. In his campaign Seymour advocated a policy of conservative, limited government, and he opposed the Reconstruction policies of the Republicans in Congress. Seymour's campaign was also marked by pronounced appeals to racism with repeated attempts to brand General Grant as the "Nigger" candidate and Seymour as the "White Man's" candidate. The Republican campaign, by contrast, was the first in which they "waved the bloody shirt", highlighting Seymour's support for mob violence against African-Americans. Though Seymour ran fairly close to Grant in the popular vote, he was defeated decisively in the electoral vote by a count of 214 to 80. Subsequent to Seymour's loss, the Fifteenth Amendment to the federal Constitution was adopted which not only guaranteed the federal right to vote for recently emancipated slaves and others of African ancestry but also compelled New York State to reinstate voting rights for such citizens.

Later years

After the presidential election, Seymour remained involved in state politics, though primarily as an elder statesman rather than an active politician. He received a number of honors during this period, including the chancellorship ofUnion College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

in 1873. In 1874 he turned down almost certain election to the United States Senate, urging the nomination instead of the eventual choice, Francis Kernan. He refused two additional efforts to nominate him for the New York governorship, in 1876 and 1879, as well as a final attempt to select him as the Democratic presidential nominee in 1880.

Never enjoying robust health, Seymour suffered a permanent decline beginning in 1876. He made a final political effort in 1884 by campaigning for Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's election as president, but deteriorated physically the following year. On July 4, 1885, he was elected to represent his maternal grandfather Gen. Jonathan Forman in the Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

in the State of New Jersey. In January 1886 his wife Mary suffered an illness. Seymour's own health worsened further. Seymour died in February 1886 and was interred in Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica, New York

Utica () is a city in the Mohawk Valley and the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The tenth-most-populous city in New York State, its population was 65,283 in the 2020 U.S. Census. Located on the Mohawk River at the fo ...

; Mary died a month later and is buried next to him.

Legacy

Cathedral of All Saints (Albany, New York)

The Cathedral of All Saints, Albany, New York, is located on Elk Street in central Albany, New York, United States. It is the central church of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany and the seat of the Episcopal Bishop of Albany. Built in the 1880s ...

.

Seymour, Wisconsin

Seymour is a city in Outagamie County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 3,451 at the 2010 census. The city is located within the Town of Seymour and the Town of Osborn.

History

Seymour was founded in 1868 and named after Governo ...

was founded in 1868 and named after Horatio Seymour.

Seymour Avenue in the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New ...

, New York, was named for him.

Electoral history

Gubernatorial elections

1868 Presidential election

Notes

See also

*Seymour-Conkling family {{unref, date=November 2018

The Seymour-Conkling family is a family of politicians from the United States.

* Horatio Seymour 1778-1857, U.S. Senator from Vermont 1821-1833.

*Henry Seymour 1780-1837, New York State Senator 1815-1819, 1821-1822. Brot ...

References

Further reading

* Furniss, Jack. "To save the union “in behalf of conservative men”: Horatio Seymour and the democratic vision for war." in ''New Perspectives on the Union War'' (Fordham University Press, 2019) pp. 63-90. * Harris, William C. ''Two Against Lincoln: Reverdy Johnson and Horatio Seymour, Champions of the Loyal Opposition'' (2017excerpt

* *

online edition

* , a standard scholarly biography. * Murdock, Eugene C. "Horatio Seymour and the 1863 draft." ''Civil War History'' 11.2 (1965): 117-141

excerpt

* , thin *

Primary sources

* Seymour, Horatio. ''Public Record: Including Speeches, Messages, Proclamations, Official Correspondence, and Other Public Utterances of Horatio Seymour; from the Campaign of 1856 to the Present Time.'' (1868online

External links

*Mr. Lincoln and New York: Horatio Seymour

*First Edition 1862 Report o

Winning New York Governor's Race.

''Speeches of Hon. Horatio Seymour : at the conventions held at Albany, January 31, 1861 and September 10, 1862''

Political Graveyard , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Seymour, Horatio 1810 births 1886 deaths American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law American Protestants Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees Democratic Party governors of New York (state) Governors of New York (state) Mayors of Utica, New York New York (state) lawyers Norwich University alumni People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Speakers of the New York State Assembly Democratic Party members of the New York State Assembly Union (American Civil War) political leaders Union (American Civil War) state governors Candidates in the 1868 United States presidential election Seymour family (U.S.) 19th-century American lawyers 19th-century American businesspeople Burials at Forest Hill Cemetery (Utica, New York)