The history of slavery in the Muslim world began with institutions inherited from

pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Informatio ...

;

[Lewis 1994]

Ch.1

and the practice of keeping

slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

subsequently developed in radically different ways, depending on social-political factors such as the

Arab slave trade

History of slavery in the Muslim world refers to various periods in which a slave trade has been carried out under the auspices of Arab peoples or Arab countries. Examples include:

* Trans-Saharan slave trade

* Indian Ocean slave trade

* Barbary s ...

. Any

non-Muslim could be enslaved.

Throughout Islamic history, slaves served in various social and economic roles, from powerful

emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

s to harshly treated manual laborers. Early on in Muslim history slaves provided

plantation labor similar to that in the early-modern Americas, but this practice was abandoned after harsh treatment led to destructive slave revolts,

[ the most notable being the ]Zanj Rebellion

The Zanj Rebellion ( ar, ثورة الزنج ) was a major revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate, which took place from 869 until 883. Begun near the city of Basra in present-day southern Iraq and led by one Ali ibn Muhammad, the insurrection invol ...

of 869–883. Slaves were widely employed in irrigation, mining, and animal husbandry, but most commonly as soldiers, guards, domestic workers,[ ]concubines

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

(sex slaves).standing armies

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

) and on slaves in administration – to such a degree that the slaves could sometimes seize power. Among black slaves, there were roughly two females to every one male.[ Two rough estimates by scholars of the numbers of just one group – black slaves held over twelve centuries in the Muslim world – are 11.5 million

and 14 million,][

]

while other estimates indicate a number between 12 and 15 million African slaves prior to the 20th century.[

]

Islam encouraged the manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

of Muslim slaves as a way of expiating sins.[Gordon 1987, p. 40.] Many early converts to Islam, such as Bilal __NOTOC__

Bilal may refer to:

People

* Bilal (name) (a list of people with the name)

* Bilal ibn Rabah, a companion of Muhammad

* Bilal (American singer)

* Bilal (Lebanese singer)

Places

* Bilal Colony, a neighbourhood of Korangi Town in Karac ...

, were former slaves. In theory, slavery in Islamic law does not have a racial or color basis, although this has not always been the case in practice. In 1990 the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam

The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (CDHRI) is a declaration of the member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) first adopted in Cairo, Egypt, on 5 August 1990, (Conference of Foreign Ministers, 9–14 Muharram ...

declared that "no one has the right to enslave" another human being. Many slaves were imported from outside the Muslim world.

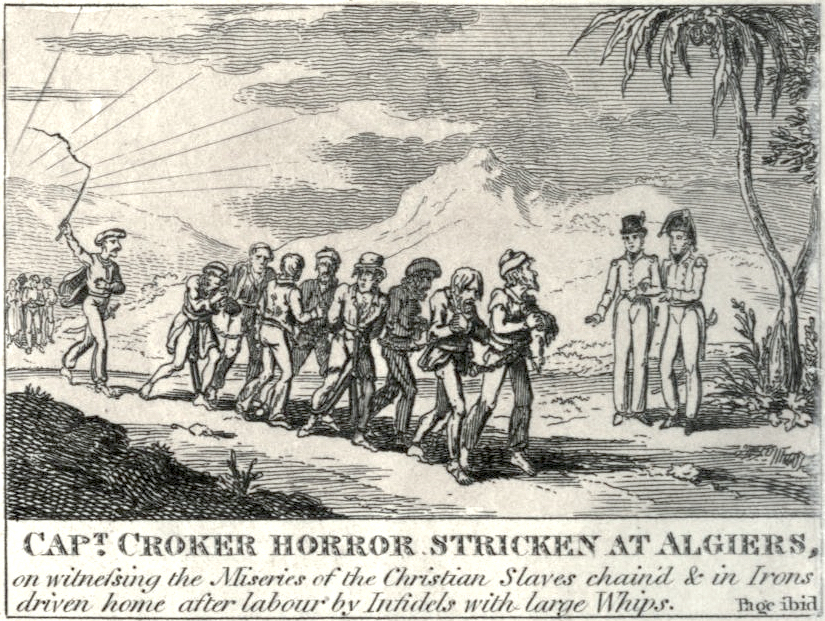

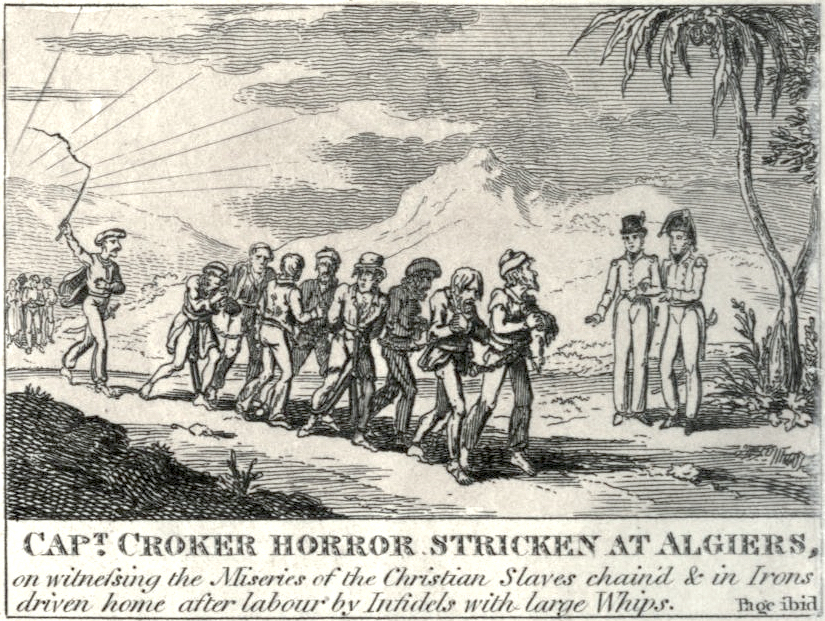

The Arab slave trade was most active in West Asia, North Africa, and Southeast Africa. The Ottoman slave trade exploited the human resources of eastern and central Europe and the Caucasus; the Barbary Coast slave traders

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of ens ...

raided the Mediterranean coasts of Europe and as far afield as the British Isles and Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. In the early 20th century (post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

), authorities gradually outlawed and suppressed slavery in Muslim lands, largely due to pressure exerted by Western nations such as Britain and France.[Brunschvig. 'Abd; '']Encyclopedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is an encyclopaedia of the academic discipline of Islamic studies published by Brill. It is considered to be the standard reference work in the field of Islamic studies. The first edition was published ...

'' Slavery in the Ottoman Empire was abolished in 1924 when the new Turkish Constitution disbanded the Imperial Harem and made the last concubines and eunuchs free citizens of the newly proclaimed republic. Slavery in Iran was abolished in 1929. Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

became the last state to abolish slavery – in 1905, 1981, and again in August 2007. Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

abolished slavery in 1970, and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the Ara ...

and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

abolished slavery in 1962 under pressure from Britain. However, slavery claiming the sanction of Islam is documented at present in the predominantly Islamic countries of the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of Ecotone, transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-a ...

,[ Segal, ''Islam's Black Slaves'', 1568: p.206][ Segal, ''Islam's Black Slaves'', 2001: p.222] and is also practiced by ISIS

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

and Boko Haram

Boko Haram, officially known as ''Jamā'at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād'' ( ar, جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد, lit=Group of the People of Sunnah for Dawah and Jihad), is an Islamic terrorist organization ...

. It is also practiced in countries like Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

and Mauritania – despite being outlawed.

Slavery in pre-Islamic Arabia

Slavery was widely practiced in pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Informatio ...

, as well as in the rest of the ancient and early medieval

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

world. The minority were European and Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

slaves of foreign extraction, likely brought in by Arab caravaners (or the product of Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

captures) stretching back to biblical times. Native Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

slaves had also existed, a prime example being Zayd ibn Harithah

Zayd ibn Haritha ( ar, زَيْد ٱبْن حَارِثَة, ') (), was an early Muslim, sahabah and the adopted son of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. He is commonly regarded as the fourth person to have accepted Islam, after Muhammad's wife Kha ...

, later to become Muhammad's adopted son. Arab slaves, however, usually obtained as captives, were generally ransomed off amongst nomad tribes.child abandonment

Child abandonment is the practice of relinquishing interests and claims over one's offspring in an illegal way, with the intent of never resuming or reasserting guardianship. The phrase is typically used to describe the physical abandonment of a ...

(see also infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of resou ...

), and by the kidnapping or sale of small children.Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

.prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

for the benefit of their masters, in accordance with Near Eastern customs.[John L Esposito (1998) p. 79]

Slavery in Islamic Arabia

Early Islamic history

W. Montgomery Watt points out that Muhammad's expansion of Pax Islamica to the Arabian peninsula reduced warfare and raiding, and therefore cut off the basis for enslaving freemen. According to Patrick Manning, Islamic legislations against abuse of slaves limited the extent of enslavement in the Arabian peninsula and, to a lesser degree, for the area of the entire Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

, where slavery had existed since the most ancient times.[Manning (1990) p. 28]

According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

, the growth of internal slave populations through natural increase was insufficient to maintain slave numbers through to modern times, which contrasts markedly with rapidly rising slave populations in the New World. He writes that

# Liberation by freemen of their own offspring born by slave mothers was "the primary drain".

# Liberation of slaves as an act of piety, was a contributing factor. Other factors include:

# Castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharm ...

: A fair proportion of male slaves were imported as eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

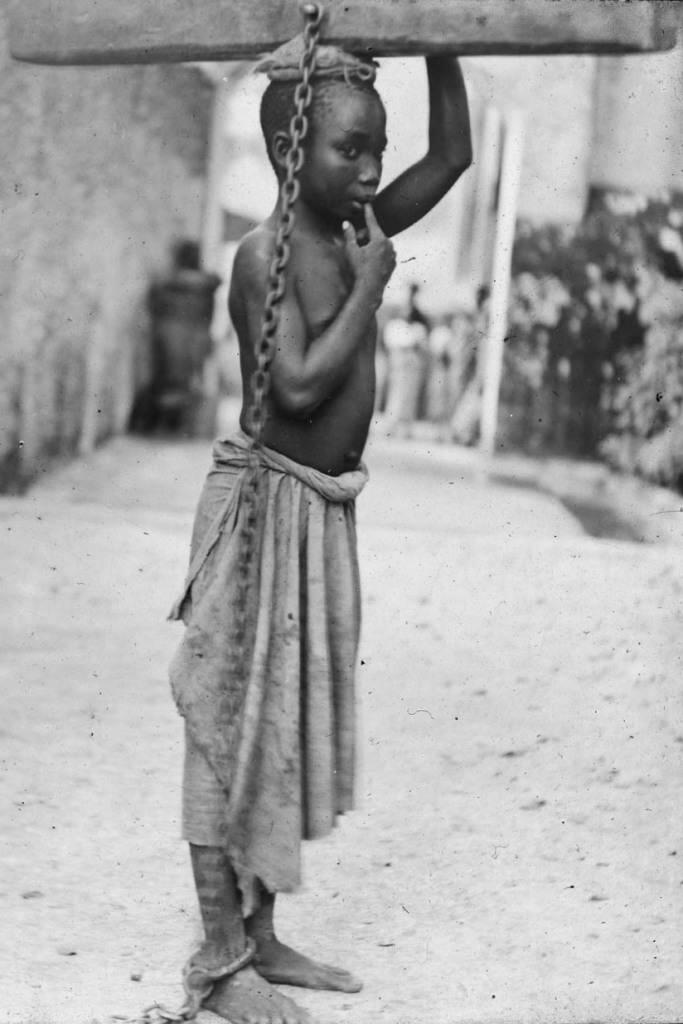

s. Levy states that according to the Quran and Islamic traditions, such emasculation was objectionable. Some jurists such as [al-Baydawi considered castration to be mutilation, stipulating laws to prevent it. However, in practice, emasculation was frequent.[ Segal, ''Islam's Black Slaves'', 2001: p.62] Children were especially at risk, and the Islamic market demand for children was much greater than the American one. Many black slaves lived in conditions conducive to malnutrition and disease, with effects on their own life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

, the fertility of women, and the infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of young children under the age of 1. This death toll is measured by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the probability of deaths of children under one year of age per 1000 live births. The under-five morta ...

rate.[ As late as the 19th century, Western travellers in North Africa and Egypt noted the high ]death rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

among imported black slaves.

# Another factor was the Zanj Rebellion

The Zanj Rebellion ( ar, ثورة الزنج ) was a major revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate, which took place from 869 until 883. Begun near the city of Basra in present-day southern Iraq and led by one Ali ibn Muhammad, the insurrection invol ...

against the plantation economy

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash ...

of ninth-century southern Iraq. Due to fears of a similar uprising among slave gangs occurring elsewhere, Muslims came to realize that large concentrations of slaves were not a suitable organization of labour and that slaves were best employed in smaller concentrations. As such, large-scale employment of slaves for manual labour became the exception rather than the norm, and the medieval Islamic world did not need to import vast numbers of slaves.[

]

Arab slave trade

Bernard Lewis writes: "In one of the sad paradoxes of human history, it was the humanitarian reforms brought by Islam that resulted in a vast development of the

Bernard Lewis writes: "In one of the sad paradoxes of human history, it was the humanitarian reforms brought by Islam that resulted in a vast development of the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

inside, and still more outside, the Islamic empire." He notes that the Islamic injunctions against the enslavement of Muslims led to the massive importation of slaves from the outside.[ According to Patrick Manning, Islam by recognizing and codifying slavery seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse.][

The 'Arab' slave trade was part of the broader 'Islamic' slave trade. Bernard Lewis writes that "polytheists and idolaters were seen primarily as sources of slaves, to be imported into the Islamic world and molded-in Islamic ways, and, since they possessed no religion of their own worth the mention, as natural recruits for Islam." Patrick Manning states that religion was hardly the point of this slavery.][Manning (1990) p.10] Also, this term suggests comparison between Islamic slave trade and Christian slave trade. Propagators of Islam in Africa often revealed a cautious attitude towards proselytizing because of its effect in reducing the potential reservoir of slaves.

In the 8th century, Africa was dominated by

In the 8th century, Africa was dominated by Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

-Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

and along the desert trails. One supply of slaves was the Solomonic dynasty

The Solomonic dynasty, also known as the House of Solomon, was the ruling dynasty of the Ethiopian Empire formed in the thirteenth century. Its members claim lineal descent from the biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Tradition asser ...

of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

which often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces, or from newly conquered or reconquered Muslim provinces. Native Muslim Ethiopian sultanates

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

exported slaves as well, such as the sometimes independent sultanate of Adal.

For a long time, until the early 18th century, the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the long ...

maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and the Middle East. Between 1530 and 1780 there were almost certainly 1 million and quite possibly as many as 1.25 million white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast of North Africa.

On the coast of the

On the coast of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

too, slave-trading posts were set up by Muslim Arabs.[Holt ''et al.'' (1970) p. 391] The archipelago of Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

, along the coast of present-day Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

, is undoubtedly the most notorious example of these trading colonies. Southeast Africa and the Indian Ocean continued as an important region for the Oriental slave trade up until the 19th century.Congo basin

The Congo Basin (french: Bassin du Congo) is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It con ...

and to discover the scale of slavery there.Tippu Tib

Tippu Tip, or Tippu Tib (1832 – June 14, 1905), real name Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī ( ar, حمد بن محمد بن جمعة بن رجب بن محمد بن سعيد المرجبي), ...

extended his influence and made many people slaves.Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is i ...

, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed. The rest of Africa had no direct contact with Muslim slave-traders.

Roles

While slaves were employed for manual labour

Manual labour (in Commonwealth English, manual labor in American English) or manual work is physical work done by humans, in contrast to labour by machines and working animals. It is most literally work done with the hands (the word ''manual ...

during the Arab slave trade, although most agricultural labor in the medieval Islamic world consisted of paid labour. Exceptions include the plantation economy

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash ...

of southern Iraq (which led to the Zanj Revolt

The Zanj Rebellion ( ar, ثورة الزنج ) was a major revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate, which took place from 869 until 883. Begun near the city of Basra in present-day southern Iraq and led by one Ali ibn Muhammad, the insurrection invol ...

), in 9th-century Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna ( ar, المغرب الأدنى), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (today's western Libya). It included all of what had previously ...

(modern-day Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

), and in 11th-century Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

(during the Karmatian state).

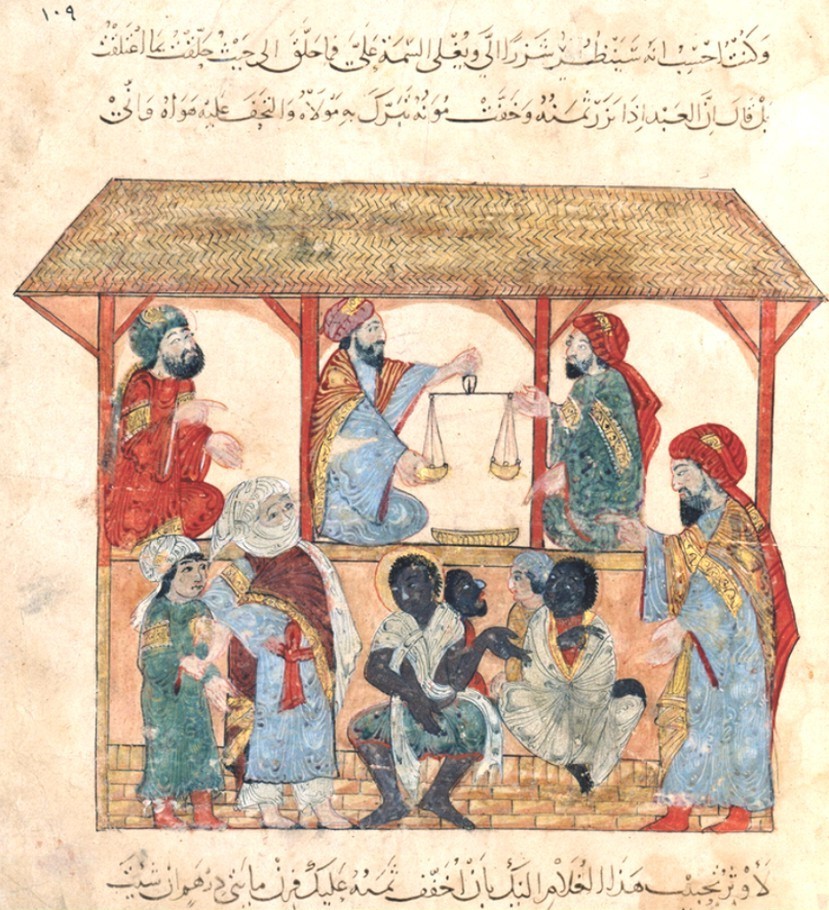

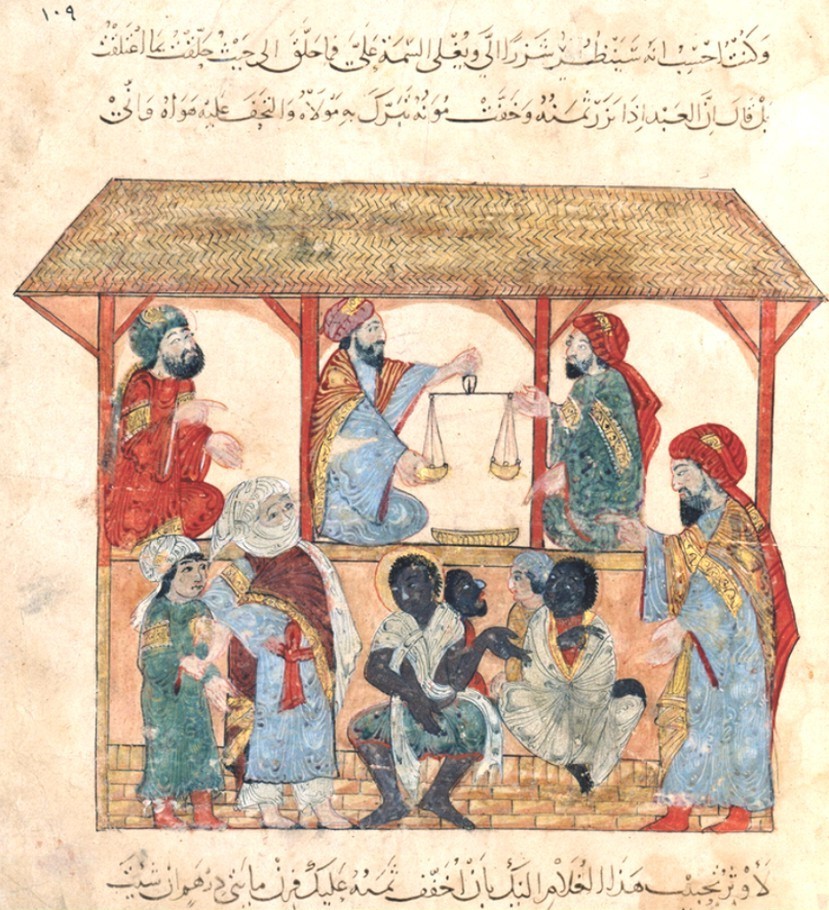

Roles of slaves

A system of plantation labor, much like that which would emerge in the Americas, developed early on, but with such dire consequences that subsequent engagements were relatively rare and reduced.[ Segal, ''Islam's Black Slaves'', 2001: p.4] Slaves in Islam were mainly directed at the service sector concubines and cooks, porters and soldiers with slavery itself primarily a form of consumption rather than a factor of production.[ The most telling evidence for this is found in the gender ratio; among slaves traded in Islamic empire across the centuries, there were roughly two females to every male.][

Outside of explicit sexual slavery, most female slaves had domestic occupations. Often, this also included sexual relations with their masters – a lawful motive for their purchase and the most common one.][Brunschvig. 'Abd; Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 13.]

Arab views on African peoples

Though the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

expresses no racial prejudice against black Africans, Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

argues that ethnocentric prejudice later developed among Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

s, for a variety of reasons:slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

; the influence of Aristotelian ideas regarding slavery, which some Muslim philosophers directed towards Zanj

Zanj ( ar, زَنْج, adj. , ''Zanjī''; fa, زنگی, Zangi) was a name used by medieval Muslim geographers to refer to both a certain portion of Southeast Africa (primarily the Swahili Coast) and to its Bantu inhabitants. This word is als ...

(Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to ...

;Ethiopians

Ethiopians are the native inhabitants of Ethiopia, as well as the global diaspora of Ethiopia. Ethiopians constitute several component ethnic groups, many of which are closely related to ethnic groups in neighboring Eritrea and other parts o ...

. By the 14th century, a significant number of slaves came from sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

; Lewis argues that this led to the likes of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

ian historian Al-Abshibi (1388–1446) writing that " is said that when the lackslave is sated, he fornicates, when he is hungry, he steals."

In 2010, at the Second Afro-Arab summit Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by '' The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

apologized for Arab involvement in the African slave trade, saying: "I regret the behavior of the Arabs... They brought African children to North Africa, they made them slaves, they sold them like animals, and they took them as slaves and traded them in a shameful way. I regret and I am ashamed when we remember these practices. I apologize for this."

Women and slavery

In Classical Arabic terminology, female slaves were generally called '' jawāri'' ( ar, جَوار, s. ''jāriya'' ar, جارِية). Slave-girls specifically might be called ''imā’'' ( ar, اِماء, s. ''ama'' ar, اَمة), while female slaves who had been trained as entertainers or courtesans were usually called '' qiyān'' ( ar, قِيان, IPA /qi'jaːn/; singular ''qayna'', ar, قَينة, IPA /'qaina/).

In Classical Arabic terminology, female slaves were generally called '' jawāri'' ( ar, جَوار, s. ''jāriya'' ar, جارِية). Slave-girls specifically might be called ''imā’'' ( ar, اِماء, s. ''ama'' ar, اَمة), while female slaves who had been trained as entertainers or courtesans were usually called '' qiyān'' ( ar, قِيان, IPA /qi'jaːn/; singular ''qayna'', ar, قَينة, IPA /'qaina/).

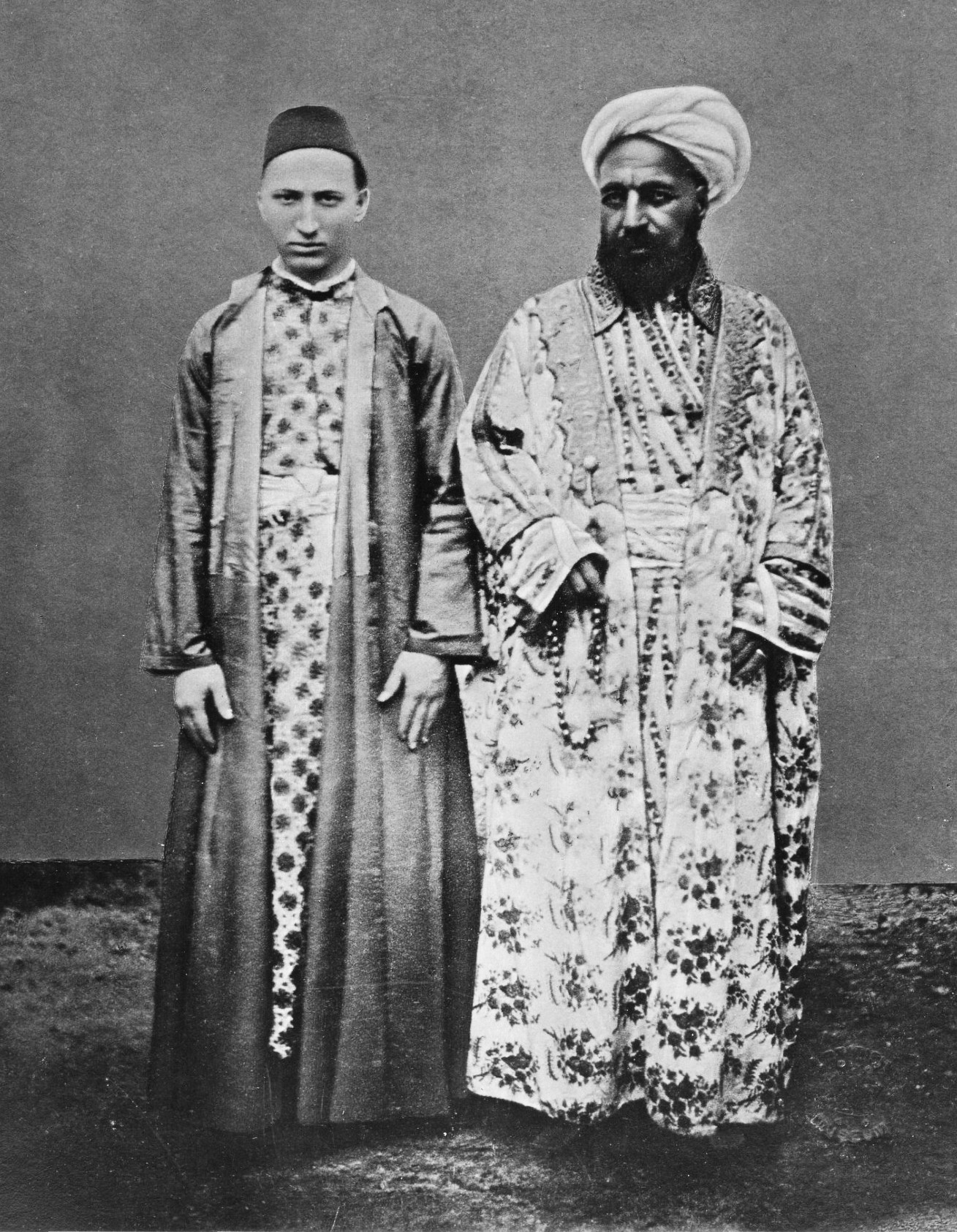

Choosing elite slaves for the grooming process

Choosing slaves to undergo the grooming process was highly selective in the Moroccan empire. There are many attributes and skills slaves can possess to win the favour and trust of their masters. When examining master/slave relationships we are able to understand that slaves with white skin were especially valued in Islamic societies. Mode of acquisition, as well as age when acquired heavily influenced slave value, as well as fostering trusting master-slave relationships. Many times, slaves acquired as adolescents or even young adults became trusted aides and confidants of their masters. Furthermore, acquiring a slave during adolescence typically leads to opportunities for education and training, as slaves acquired in their adolescent years were at an ideal age to begin military training. In Islamic societies, it was normal to begin this process at the age of ten, lasting until the age of fifteen, at which point these young men would be considered ready for military service. Slaves with specialised skills were highly valued in Islamic slave societies. Christian slaves were often required to speak and write in Arabic. Having slaves fluent in English and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

was a highly valued tool for diplomatic affairs. Bi-lingual slaves like Thomas Pellow

Thomas Pellow (1704 – 45), son of Thomas Pellow of Penryn and his wife Elizabeth (née Lyttleton), was a Cornish author best known for the extensive captivity narrative entitled ''The History of the Long Captivity and Adventures of Thomas P ...

used their translating ability for important matters of diplomacy. Pellow himself worked as a translator for the ambassador in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

.

Rebellion

In some cases, slaves would join domestic rebellions or even rise up against governors. The most renowned of these rebellions was the Zanj Rebellion

The Zanj Rebellion ( ar, ثورة الزنج ) was a major revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate, which took place from 869 until 883. Begun near the city of Basra in present-day southern Iraq and led by one Ali ibn Muhammad, the insurrection invol ...

.

The Zanj Revolt took place near the city of Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

, located in southern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, over a period of fifteen years (869–883 AD). It grew to involve over 500,000 slaves imported from across the Muslim empire, and claimed over “tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq”.Ali ibn Abu Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

.Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

central government.

Political power

Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s were slave-soldiers who were converted to Islam, and served the Muslim caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

s and the Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

sultans during the Middle Ages. Over time, they became a powerful military caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultur ...

, often defeating the Crusaders and, on more than one occasion, they seized power for themselves, for example, ruling Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

in the Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16t ...

from 1250 to 1517.

European slaves

Saqaliba

Saqaliba ( ar, صقالبة, ṣaqāliba, singular ar, صقلبي, ṣaqlabī) is a term used in medieval Arabic sources to refer to Slavs and other peoples of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, or in a broad sense to European slaves. The t ...

is a term used in medieval Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

sources to refer to Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

and other peoples of Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

, Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

, and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

, or in a broad sense to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an slaves under Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

Islamic rule.

Through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

up until the early modern period, a major source of slaves sent to Muslim lands was Central and Eastern Europe. Slaves of Northwestern Europe

Northwestern Europe, or Northwest Europe, is a loosely defined subregion of Europe, overlapping Northern and Western Europe. The region can be defined both geographically and ethnographically.

Geographic definitions

Geographically, North ...

were also favored. The slaves captured were sent to Islamic lands like Spain and Egypt through France and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

served as a major centre for castration of Slavic captives. The Emirate of Bari

The Emirate of Bari was a short-lived Islamic state in Apulia ruled by non-Arabs, probably Berbers and Black Africans. Controlled from the South Italian city of Bari, it was established about 847 when the region was taken from the Byzantine Empire, ...

also served as an important port for trade of such slaves. After the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

blocked Arab merchants from European ports, Arabs started importing slaves from the Caucasus and Caspian Sea regions, shipping them off as far east as Transoxiana in Central Asia. Despite this, slaves taken in battle or from minor raids in continental Europe remained a steady resource in many regions. The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

used slaves from the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and Eastern Europe. The Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

were primarily composed of enslaved Europeans. Slaving raids by Barbary Pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe ...

on the coasts of Western Europe as far as Iceland remained a source of slaves until suppressed in the early 19th century. Common roles filled by European slaves ranged from laborers to concubines, and even soldiers.

Slavery in India

In the Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the 8th century, the armies of the Umayyad commander Muhammad bin Qasim

Muḥammad ibn al-Qāsim al-Thaqāfī ( ar, محمد بن القاسم الثقفي; –) was an Arab military commander in service of the Umayyad Caliphate who led the Muslim conquest of Sindh (part of modern Pakistan), inaugurating the Umayy ...

enslaved tens of thousands of Indian prisoners, including both soldiers and civilians. In the early 11th century Tarikh al-Yamini, the Arab historian Al-Utbi recorded that in 1001 the armies of Mahmud of Ghazna

Yamīn-ud-Dawla Abul-Qāṣim Maḥmūd ibn Sebüktegīn ( fa, ; 2 November 971 – 30 April 1030), usually known as Mahmud of Ghazni or Mahmud Ghaznavi ( fa, ), was the founder of the Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty, ruling from 998 to 1030. At th ...

conquered Peshawar

Peshawar (; ps, پېښور ; hnd, ; ; ur, ) is the sixth most populous city in Pakistan, with a population of over 2.3 million. It is situated in the north-west of the country, close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is ...

and Waihand

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

(capital of Gandhara) after the Battle of Peshawar in 1001, "in the midst of the land of Hindustan

''Hindūstān'' ( , from '' Hindū'' and ''-stān''), also sometimes spelt as Hindōstān ( ''Indo-land''), along with its shortened form ''Hind'' (), is the Persian-language name for the Indian subcontinent that later became commonly used b ...

", and captured some 100,000 youths. Later, following his twelfth expedition into India in 1018–19, Mahmud is reported to have returned with such a large number of slaves that their value was reduced to only two to ten ''dirham

The dirham, dirhem or dirhm ( ar, درهم) is a silver unit of currency historically and currently used by several Arab world, Arab and Arabization, Arab influenced states. The term has also been used as a related unit of mass.

Unit of ...

s'' each. This unusually low price made, according to Al-Utbi, "merchants omefrom distant cities to purchase them, so that the countries of Central Asia, Iraq and Khurasan were swelled with them, and the fair and the dark, the rich and the poor, mingled in one common slavery". Elliot and Dowson refer to "five hundred thousand slaves, beautiful men, and women.". Later, during the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526). period (1206–1555), references to the abundant availability of low-priced Indian slaves abound. Levi attributes this primarily to the vast human resources of India, compared to its neighbors to the north and west (India's Mughal population being approximately 12 to 20 times that of Turan and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

at the end of the 16th century).

The Delhi sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526). obtained thousands of slaves and eunuch servants from the villages of Eastern Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

(a widespread practice which Mughal emperor Jahangir

Nur-ud-Din Muhammad Salim (30 August 1569 – 28 October 1627), known by his imperial name Jahangir (; ), was the fourth Mughal Emperor, who ruled from 1605 until he died in 1627. He was named after the Indian Sufi saint, Salim Chishti.

Ear ...

later tried to stop). Wars, famines and pestilences drove many villagers to sell their children as slaves. The Muslim conquest of Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

in Western India had two main objectives. The conquerors demanded and more often forcibly wrested both Hindu women as well as land owned by Hindus. Enslavement of women invariably led to their conversion to Islam. In battles waged by Muslims against Hindus in Malwa

Malwa is a historical region of west-central India occupying a plateau of volcanic origin. Geologically, the Malwa Plateau generally refers to the volcanic upland north of the Vindhya Range. Politically and administratively, it is also sy ...

and the Deccan plateau

The large Deccan Plateau in southern India is located between the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, and is loosely defined as the peninsular region between these ranges that is south of the Narmada river. To the north, it is bounded by th ...

, a large number of captives were taken. Muslim soldiers were permitted to retain and enslave prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

as plunder.

The first Bahmani sultan, Alauddin Bahman Shah is noted to have captured 1,000 singing and dancing girls from Hindu temples after he battled the northern Carnatic chieftains. The later Bahmanis also enslaved civilian women and children in wars; many of them were converted to Islam in captivity.

During the rule of Shah Jahan

Shihab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram (5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), better known by his regnal name Shah Jahan I (; ), was the fifth emperor of the Mughal Empire, reigning from January 1628 until July 1658. Under his emperorship, the Mugha ...

, many peasants were compelled to sell their women and children into slavery to meet the land revenue demand.

Slavery in the Seljuk and Ottoman Empires

After the Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

conquered parts of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, they brought to the devastated lands Greek, Armenian and Syrian farmers after enslaving entire Byzantine and Armenian villages and towns.

Slavery was a legal and important part of the economy of the Ottoman Empire and Ottoman society until the slavery of Caucasians was banned in the early 19th century, although slaves from other groups were still permitted. In Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

(present-day Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

), the administrative and political center of the Empire, about a fifth of the population consisted of slaves in 1609. Even after several measures to ban slavery in the late 19th century, the practice continued largely uninterrupted into the early 20th century. As late as 1908, female slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire. Concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubin ...

was a central part of the Ottoman slave system throughout the history of the institution.[Madeline C. Zilfi ''Women and slavery in the late Ottoman Empire'' Cambridge University Press, 2010]

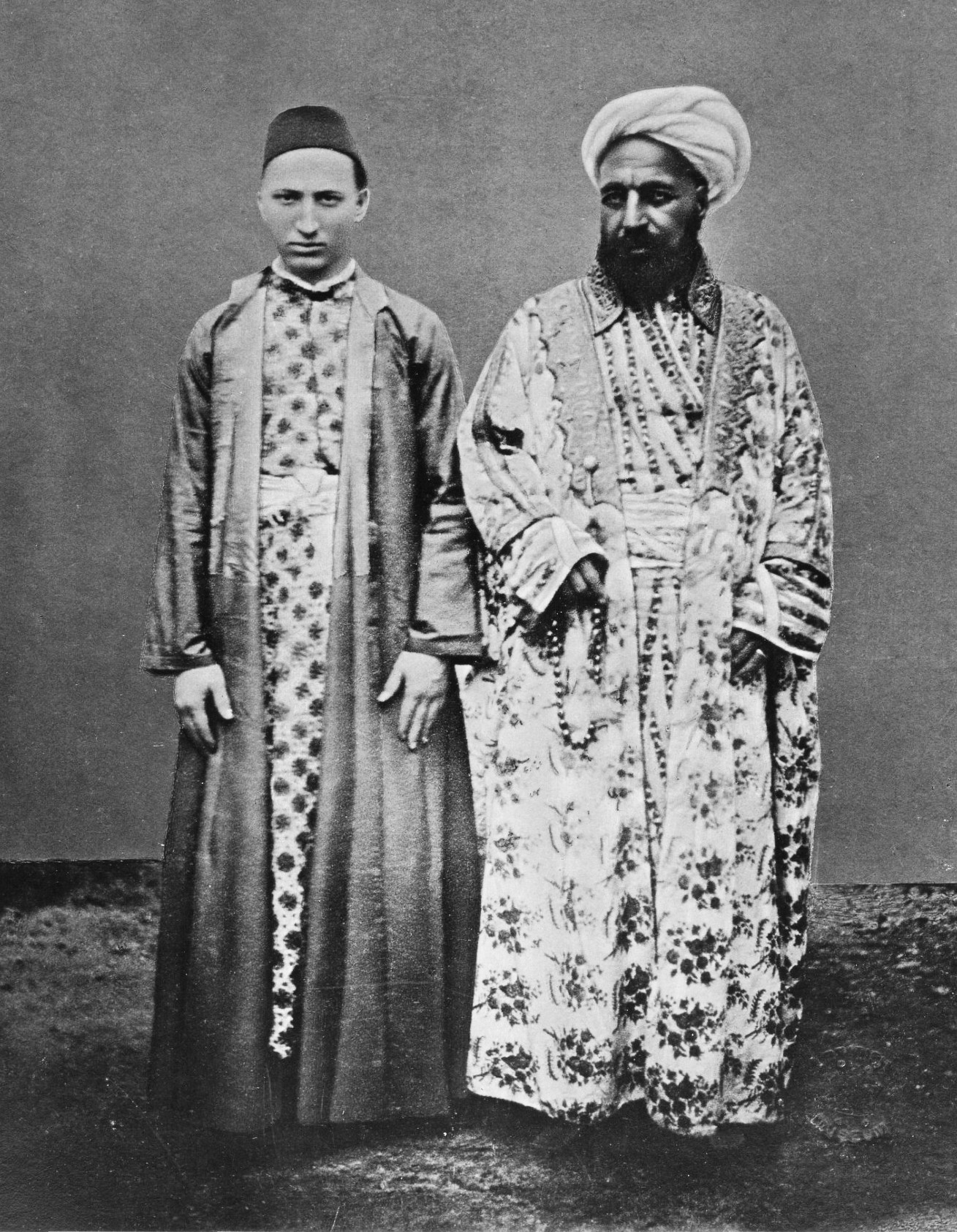

A member of the Ottoman slave class, called a '' kul'' in Turkish, could achieve high status. Black castrated slaves, were tasked to guard the imperial harems, while white castrated slaves filled administrative functions.

A member of the Ottoman slave class, called a '' kul'' in Turkish, could achieve high status. Black castrated slaves, were tasked to guard the imperial harems, while white castrated slaves filled administrative functions. Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

were the elite soldiers of the imperial armies, collected in childhood as a " blood tax", while galley slaves

A galley slave was a slave rowing in a galley, either a convicted criminal sentenced to work at the oar (''French'': galérien), or a kind of human chattel, often a prisoner of war, assigned to the duty of rowing.

In the ancient Mediterranean ...

captured in slave raids or as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, manned the imperial vessels. Slaves were often to be found at the forefront of Ottoman politics. The majority of officials in the Ottoman government were bought slaves, raised free, and integral to the success of the Ottoman Empire from the 14th century into the 19th. Many officials themselves owned a large number of slaves, although the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

himself owned by far the largest number.devşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

'', a sort of "blood tax" or "child collection", young Christian boys from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

were taken from their homes and families, brought up as Muslims, and enlisted into the most famous branch of the '' Kapıkulu'', the Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

, a special soldier class of the Ottoman army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

that became a decisive faction in the Ottoman invasions of Europe. Most of the military commanders of the Ottoman forces, imperial administrators, and ''de facto'' rulers of the Empire, such as Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha

Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha ("Ibrahim Pasha of Parga"; c. 1495 – 15 March 1536), also known as Frenk Ibrahim Pasha ("the Westerner"), Makbul Ibrahim Pasha ("the Favorite"), which later changed to Maktul Ibrahim Pasha ("the Executed") after his ex ...

and Sokollu Mehmed Pasha

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha ( ota, صوقوللى محمد پاشا, Ṣoḳollu Meḥmed Pașa, tr, Sokollu Mehmet Paşa; ; ; 1506 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in ...

, were recruited in this way.

Slavery in Sultanates of Southeast Asia

In the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

, slavery was common until the end of the 19th century. The slave trade was centered on the Muslim Sultanates in the Sulu Sea

The Sulu Sea ( fil, Dagat Sulu; Tausug: ''Dagat sin Sūg''; Chavacano: ''Mar de Sulu''; Cebuano: ''Dagat sa Sulu''; Hiligaynon: ''Dagat sang Sulu''; Karay-a: ''Dagat kang Sulu''; Cuyonon: ''Dagat i'ang Sulu''; ms, Laut Sulu) is a body o ...

: the Sultanate of Sulu

The Sultanate of Sulu ( Tausūg: ''Kasultanan sin Sūg'', كاسولتانن سين سوڬ; Malay: ''Kesultanan Sulu''; fil, Sultanato ng Sulu; Chavacano: ''Sultanato de Sulu/Joló''; ar, سلطنة سولك) was a Muslim state that ruled ...

, the Sultanate of Maguindanao

The Sultanate of Maguindanao ( Maguindanaon: ''Kasultanan nu Magindanaw''; Old Maguindanaon: كاسولتانن نو ماڬينداناو; Jawi: کسلطانن ماڬيندناو; Iranun: ''Kesultanan a Magindanao''; ms, Kesultanan Magindan ...

, and the Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao (the modern Moro people

The Moro people or Bangsamoro people are the 13 Muslim-majority ethnolinguistic Austronesian groups of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan, native to the region known as the Bangsamoro (lit. ''Moro nation'' or ''Moro country''). As Muslim-majorit ...

). Also the Aceh Sultanate

The Sultanate of Aceh, officially the Kingdom of Aceh Darussalam ( ace, Keurajeuën Acèh Darussalam; Jawoë: كاورجاون اچيه دارالسلام), was a sultanate centered in the modern-day Indonesian province of Aceh. It was a major ...

on Sumatra took part in the slave trade. The economies of these sultanates relied heavily on the slave trade.Banguingui

Banguingui, also known as Sama Banguingui or Samal Banguingui (alternative spellings include Bangingi’, Bangingi, Banguingui, Balanguingui, and Balangingi) is a distinct ethnolinguistic group native to Balanguingui Island but also dispersed ...

slavers. These were taken by piracy from passing ships as well as coastal raids on settlements as far as the Malacca Strait, Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, the southern coast of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and the islands beyond the Makassar Strait

Makassar Strait is a strait between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi in Indonesia. To the north it joins the Celebes Sea, while to the south it meets the Java Sea. To the northeast, it forms the Sangkulirang Bay south of the Mangkalihat Pen ...

. Most of the slaves were Tagalogs

The Tagalog people ( tl, Mga Tagalog; Baybayin: ᜋᜅ ᜆᜄᜎᜓᜄ᜔) are the largest ethnolinguistic group in the Philippines, numbering at around 30 million. An Austronesian people, the Tagalog have a well developed society due to their cu ...

, Visayans

Visayans ( Visayan: ''mga Bisaya''; ) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. When taken as a single ethnic group ...

, and "Malays" (including Bugis

The Bugis people (pronounced ), also known as Buginese, are an ethnicity—the most numerous of the three major linguistic and ethnic groups of South Sulawesi (the others being Makassar and Toraja), in the south-western province of Sulawesi ...

, Mandarese, Iban

IBAN or Iban or Ibán may refer to:

Banking

* International Bank Account Number

Ethnology

* Iban culture

* Iban language

* Iban people

Given name

Cycling

* Iban Iriondo (born 1984)

* Iban Mayo (born 1977)

* Iban Mayoz (born 1981)

Football

* ...

, and Makassar

Makassar (, mak, ᨆᨀᨔᨑ, Mangkasara’, ) is the capital of the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, Surabaya, Meda ...

). There were also occasional European and Chinese captives who were usually ransomed off through Tausug intermediaries of the Sulu Sultanate

The Sultanate of Sulu ( Tausūg: ''Kasultanan sin Sūg'', كاسولتانن سين سوڬ; Malay: ''Kesultanan Sulu''; fil, Sultanato ng Sulu; Chavacano: ''Sultanato de Sulu/Joló''; ar, سلطنة سولك) was a Muslim state that ruled ...

. The scale of this activity was so massive that the word for "pirate" in Malay became ''Lanun'', an

The scale of this activity was so massive that the word for "pirate" in Malay became ''Lanun'', an exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group ...

of the Iranun people. Male captives of the Iranun and the Banguingui were treated brutally, even fellow Muslim captives were not spared. They were usually forced to serve as galley slave

A galley slave was a slave rowing in a galley, either a convicted criminal sentenced to work at the oar (''French'': galérien), or a kind of human chattel, often a prisoner of war, assigned to the duty of rowing.

In the ancient Mediterranean ...

s on the ''lanong

''Lanong'' were large outrigger warships used by the Iranun and the Banguingui people of the Philippines. They could reach up to in length and had two biped shear masts which doubled as boarding ladders. They also had one to three banks of oars ...

'' and '' garay'' warships of their captors. Within a year of capture, most of the captives of the Iranun and Banguingui would be bartered off in Jolo

Jolo ( tsg, Sūg) is a volcanic island in the southwest Philippines and the primary island of the province of Sulu, on which the capital of the same name is situated. It is located in the Sulu Archipelago, between Borneo and Mindanao, and has ...

usually for rice, opium, bolts of cloth, iron bars, brassware, and weapons. The buyers were usually Tausug ''datu

''Datu'' is a title which denotes the rulers (variously described in historical accounts as chiefs, sovereign princes, and monarchs) of numerous indigenous peoples throughout the Philippine archipelago. The title is still used today, especial ...

'' from the Sultanate of Sulu

The Sultanate of Sulu ( Tausūg: ''Kasultanan sin Sūg'', كاسولتانن سين سوڬ; Malay: ''Kesultanan Sulu''; fil, Sultanato ng Sulu; Chavacano: ''Sultanato de Sulu/Joló''; ar, سلطنة سولك) was a Muslim state that ruled ...

who had preferential treatment, but buyers also included European (Dutch and Portuguese) and Chinese traders as well as Visayan pirates (''renegados'').slave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets became a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Slave markets in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire during the mid-14th century, slaves were traded in special ...

s. By the 1850s, slaves constituted 50% or more of the population of the Sulu archipelago.alipin

The ''alipin'' refers to the lowest social class among the various cultures of the Philippines before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the Visayan languages, the equivalent social classes were known as the ''oripu ...

'' elsewhere in the Philippines). The bondsmen were natives enslaved to pay off debt or crime. They were slaves only in terms of their temporary service requirement to their master, but retained most of the rights of the freemen, including protection from physical harm and the fact that they could not be sold. The ''banyaga'', on the other hand, had little to no rights. Spanish authorities and native Christian Filipinos responded to the Moro slave raids by building watchtowers and forts across the Philippine archipelago, many of which are still standing today. Some provincial capitals were also moved further inland. Major command posts were built in

Spanish authorities and native Christian Filipinos responded to the Moro slave raids by building watchtowers and forts across the Philippine archipelago, many of which are still standing today. Some provincial capitals were also moved further inland. Major command posts were built in Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

, Cavite

Cavite, officially the Province of Cavite ( tl, Lalawigan ng Kabite; Chavacano: ''Provincia de Cavite''), is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region in Luzon. Located on the southern shores of Manila Bay and southw ...

, Cebu

Cebu (; ceb, Sugbo), officially the Province of Cebu ( ceb, Lalawigan sa Sugbo; tl, Lalawigan ng Cebu; hil, Kapuroan sang Sugbo), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and 16 ...

, Iloilo

Iloilo (), officially the Province of Iloilo ( hil, Kapuoran sang Iloilo; krj, Kapuoran kang Iloilo; tl, Lalawigan ng Iloilo), is a province in the Philippines located in the Western Visayas region. Its capital is the City of Iloilo, the ...

, Zamboanga, and Iligan

Iligan, officially the City of Iligan ( ceb, Dakbayan sa Iligan; fil, Lungsod ng Iligan; Maranao: ''Inged a Iligan''), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in the region of Northern Mindanao, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it ha ...

. Defending ships were also built by local communities, especially in the Visayas Islands, including the construction of war "''barangayanes''" (''balangay

A Balangay, or barangay is a type of lashed-lug boat built by joining planks edge-to-edge using pins, dowels, and fiber lashings. They are found throughout the Philippines and were used largely as trading ships up until the colonial era. The ...

'') that were faster than the Moro raiders' ships and could give chase. As resistance against raiders increased, ''Lanong

''Lanong'' were large outrigger warships used by the Iranun and the Banguingui people of the Philippines. They could reach up to in length and had two biped shear masts which doubled as boarding ladders. They also had one to three banks of oars ...

'' warships of the Iranun were eventually replaced by the smaller and faster '' garay'' warships of the Banguingui in the early 19th century. The Moro raids were eventually subdued by several major naval expeditions by the Spanish and local forces from 1848 to 1891, including retaliatory bombardment and capture of Moro settlements. By this time, the Spanish had also acquired steam gunboats (''vapor''), which could easily overtake and destroy the native Moro warships.Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely surrounded by th ...

, Sulu, and Maguindanao. This eventually led to the collapse of the latter two states and contributed to the widespread poverty of the Moro region in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

today. By the 1850s, most slaves were local-born from slave parents as the raiding became more difficult. By the end of the 19th century and the conquest of the Sultanates by the Spanish and the Americans, the slave population was largely integrated into the native population as citizens under the Philippine government.Sultanate of Gowa

The Sultanate of Gowa (sometimes written as ''Goa''; not to be confused with Goa in India) was one of the great kingdoms in the history of Indonesia and the most successful kingdom in the South Sulawesi region. People of this kingdom come fr ...

of the Bugis people

The Bugis people (pronounced ), also known as Buginese, are an ethnicity—the most numerous of the three major linguistic and ethnic groups of South Sulawesi (the others being Makassar and Toraja), in the south-western province of Sulawesi ...

also became involved in the Sulu slave trade. They purchased slaves (as well as opium and Bengali cloth) from the Sulu Sea sultanates, then re-sold the slaves in the slave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets became a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Slave markets in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire during the mid-14th century, slaves were traded in special ...

s in the rest of Southeast Asia. Several hundred slaves (mostly Christian Filipinos) were sold by the Bugis annually in Batavia, Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has bee ...

, Bantam, Cirebon

Cirebon (, formerly rendered Cheribon or Chirebon in English) is a port city on the northern coast of the Indonesian island of Java. It is the only coastal city of West Java, located about 40 km west of the provincial border with Central J ...

, Banjarmasin

)

, translit_lang1 = Other

, translit_lang1_type1 = Jawi

, translit_lang1_info1 = بنجر ماسين

, settlement_type = City

, motto = ''Kayuh Baimbai'' ( Banjare ...

, and Palembang

Palembang () is the capital city of the Indonesian province of South Sumatra. The city proper covers on both banks of the Musi River on the eastern lowland of southern Sumatra. It had a population of 1,668,848 at the 2020 Census. Palembang ...

by the Bugis. The slaves were usually sold to Dutch and Chinese families as servants, sailors, laborers, and concubines. The sale of Christian Filipinos (who were Spanish subjects) in Dutch-controlled cities led to formal protests by the Spanish Empire to the Netherlands and its prohibition in 1762 by the Dutch, but it had little effect due to lax or absent enforcement. The Bugis slave trade was only stopped in the 1860s, when the Spanish navy from Manila started patrolling Sulu waters to intercept Bugis slave ships and rescue Filipino captives. Also contributing to the decline was the hostility of the Sama-Bajau raiders in Tawi-Tawi

Tawi-Tawi, officially the Province of Tawi-Tawi ( tl, Lalawigan ng Tawi-Tawi; Tausug: ''Wilaya' sin Tawi-Tawi''; Sinama: ''Jawi Jawi/Jauih Jauih''), is an island province in the Philippines located in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim ...

who broke off their allegiance to the Sultanate of Sulu in the mid-1800s and started attacking ships trading with the Tausug ports.Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

as late as 1891, there was a regular trade in Chinese slaves by Muslim slaveowners, with girls and women sold for concubinage. However, the buying of Chinese girls in Singapore was forbidden for Muslims by a Batavia (Jakarta) based Arab Muslim Mufti, Usman bin Yahya

Usman bin Yahya, Utsman ibn Yahya or Othman bin Yahya ( ar-at, عثمان بن يحيى , ‘Uthmān bin Yahyā; full name: ( ar-at, سيد عثمان بن عبد الله بن عقيل بن يحيى العلوي, Sayyid ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Abda ...

in a fatwa because he ruled that in Islam it was illegal to buy free non-Muslims or marry non-Muslim slave girls during peace time from slave dealers and non-Muslims could only be enslaved and purchased during holy war (jihad).

A Chinese non-Muslim man had a female concubine who was of Muslim Arab Hadhrami Sayyid origin in Solo

Solo or SOLO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Comics

* ''Solo'' (DC Comics), a DC comics series

* Solo, a 1996 mini-series from Dark Horse Comics

Characters

* Han Solo, a ''Star Wars'' character

* Jacen Solo, a Jedi in the non-canonical ''S ...

, the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, in 1913 which was scandalous in the eyes of Ahmad Surkati

Ahmad Surkati ( ar, احمد بن محمد السركتي; ; ; 1875 CE – 6 September 1943) was the founder of the organization Jam'iyat al-Islah wa Al-Irsyad al-Arabiyah (''Arab Association for Reform and Guidance''), which later transformed i ...

and his Al-Irshad Al-Islamiya

Al-Irshad Al-Islamiya Association ( ar-at, جمعية الإصلاح والإرشاد الإسلاميه, Jam'iyat al-Ishlah wal Irshad al-Islamiyya) is an organization in Indonesia engaged in educational and religious activities. The organizati ...

.Jeddah

Jeddah ( ), also spelled Jedda, Jiddah or Jidda ( ; ar, , Jidda, ), is a city in the Hejaz region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and the country's commercial center. Established in the 6th century BC as a fishing village, Jeddah's pro ...

, Kingdom of Hejaz

The Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz ( ar, المملكة الحجازية الهاشمية, ''Al-Mamlakah al-Ḥijāziyyah Al-Hāshimiyyah'') was a state in the Hejaz region in the Middle East that included the western portion of the Arabian Penins ...

on the Arabian peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

, the Arab king Ali bin Hussein, King of Hejaz

Ali bin Hussein, GBE ( ar, علي بن الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, translit=Alī ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Alī el-Hâşimî; 18791935), was King of Hejaz and Grand Sharif of Mecca from October 1924 until he was deposed by Abdulaziz bin ...

had in his palace 20 young pretty Javanese girls from Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

(modern day Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

).

19th and 20th centuries

The strong abolitionist movement in the 19th century in England and later in other Western countries

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. influenced slavery in Muslim lands. Appalling loss of life and hardships often resulted from the processes of acquisition and transportation of slaves to Muslim lands and this drew the attention of European opponents of slavery. Continuing pressure from European countries eventually overcame the strong resistance of religious conservatives who were holding that forbidding what God permits is just as great an offense as to permit what God forbids. Slavery, in their eyes, was "authorized and regulated by the holy law". Even masters persuaded of their own piety and benevolence sexually exploited their concubines, without a thought of whether this constituted a violation of their humanity.[ Segal, ''Islam's Black Slaves'', 2001: p. 5] There were also many pious Muslims who refused to have slaves and persuaded others not to do so. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire's orders against the traffic of slaves were issued and put into effect.sex slaves

Sexual slavery and sexual exploitation is an attachment of any ownership right over one or more people with the intent of coercing or otherwise forcing them to engage in sexual activities. This includes forced labor, reducing a person to a ...

, and even chattel exists even today in some Muslim countries (though some have questioned the use of the term slavery as an accurate description).[James R. Lewis and Carl Skutsch, ''The Human Rights Encyclopedia'', v.3, p. 898-904]

According to a March 1886 article in ''The New York Times'', the Ottoman Empire allowed a slave trade in girls to thrive during the late 1800s, while publicly denying it. Girl sexual slaves sold in the Ottoman Empire were mainly of three ethnic groups: Circassian,

According to a March 1886 article in ''The New York Times'', the Ottoman Empire allowed a slave trade in girls to thrive during the late 1800s, while publicly denying it. Girl sexual slaves sold in the Ottoman Empire were mainly of three ethnic groups: Circassian, Syrian

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

, and Nubian

Nubian may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Nubia, a region along the Nile river in Southern Egypt and northern Sudan.

*Nubian people

*Nubian languages

*Anglo-Nubian goat, a breed of goat

* Nubian ibex

* , several ships of the Britis ...

. Circassian girls were described by the American journalist as fair and light-skinned. They were frequently sent by Circassian leaders as gifts to the Ottomans. They were the most expensive, reaching up to 500 Turkish lira

The lira ( tr, Türk lirası; sign: ₺; ISO 4217 code: TRY; abbreviation: TL) is the official currency of Turkey and Northern Cyprus. One lira is divided into one hundred '' kuruş''.

History

Ottoman lira (1844–1923)

The lira, along wi ...

and the most popular with the Turks. The next most popular slaves were Syrian girls, with "dark eyes and hair", and light brown skin. Their price could reach to thirty ''lira''. They were described by the American journalist as having "good figures when young". Throughout coastal regions in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Syrian girls were sold. The ''New York Times'' journalist stated Nubian girls were the cheapest and least popular, fetching up to 20 lira.