History Of Immigration To The United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of immigration to the United States details the movement of people to the

European immigrants joined the Prior to 1890, the individual states, rather than the Federal government, regulated immigration into the United States. The Immigration Act of 1891 established a Commissioner of Immigration in the Treasury Department. The

Prior to 1890, the individual states, rather than the Federal government, regulated immigration into the United States. The Immigration Act of 1891 established a Commissioner of Immigration in the Treasury Department. The  The

The  Over two million

Over two million

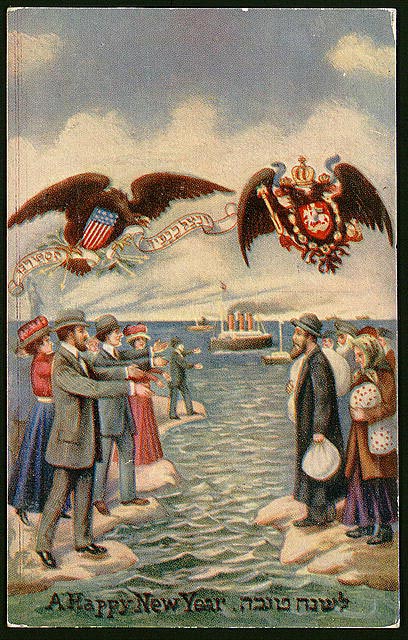

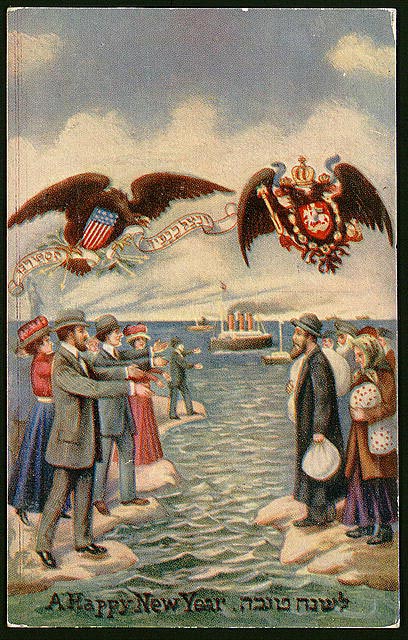

"New immigration" was a term from the late 1880s that refers to the influx of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (areas that previously sent few immigrants). The great majority came through

"New immigration" was a term from the late 1880s that refers to the influx of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (areas that previously sent few immigrants). The great majority came through

At the end of World War II, "regular" immigration almost immediately increased under the official national origins quota system as refugees from war-torn Europe began immigrating to the U.S. After the war, there were jobs for nearly everyone who wanted one, when most women employed during the war went back into the home. From 1941 to 1950, 1,035,000 people immigrated to the U.S., including 226,000 from Germany, 139,000 from the UK, 171,000 from Canada, 60,000 from Mexico, and 57,000 from Italy.

The

At the end of World War II, "regular" immigration almost immediately increased under the official national origins quota system as refugees from war-torn Europe began immigrating to the U.S. After the war, there were jobs for nearly everyone who wanted one, when most women employed during the war went back into the home. From 1941 to 1950, 1,035,000 people immigrated to the U.S., including 226,000 from Germany, 139,000 from the UK, 171,000 from Canada, 60,000 from Mexico, and 57,000 from Italy.

The

excerpt

* Barkan, Elliott Robert. ''And Still They Come: Immigrants and American Society, 1920 to the 1990s'' (1996), by leading historian * Barkan, Elliott Robert, ed. ''A Nation of Peoples: A Sourcebook on America's Multicultural Heritage'' (1999), 600 pp; essays by scholars on 27 groups * Barone, Michael. ''The New Americans: How the Melting Pot Can Work Again'' (2006) * Bayor, Ronald H., ed. ''The Oxford Handbook of American Immigration and Ethnicity'' (2015) * Bodnar, John. ''The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America'' (1985) * Dassanowsky, Robert, and Jeffrey Lehman, eds. ''Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America'' (2nd ed. 3 vol 2000), anthropological approach to 150 culture groups; 1974 pp * Gerber, David A. ''American immigration: A very short introduction'' (2021)

excerpt

* Gjerde, Jon, ed. ''Major Problems in American Immigration and Ethnic History'' (1998) primary sources and excerpts from scholars. * Kenny, Kevin. "Mobility and Sovereignty: The Nineteenth-Century Origins of Immigration Restriction." ''Journal of American History'' 109.2 (2022): 284-297. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaac233 * Levinson, David and Melvin Ember, eds. ''American Immigrant Cultures'' 2 vol (1997) covers all major and minor groups * Meier, Matt S. and Gutierrez, Margo, eds. ''The Mexican American Experience: An Encyclopedia'' (2003) () * Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar, eds

''Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups''

Harvard University Press, , the standard reference, covering all major groups and most minor group

online

* Wyman, Mark. ''Round-Trip to America: The Immigrants Return to Europe, 1880–1930'' (Cornell UP, 1993).

"Does Immigration Grease the Wheels of the Labor Market?"

''Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2001'' * Fragomen Jr, Austin T. "The illegal immigration reform and immigrant responsibility act of 1996: An overview." ''International Migration Review'' 31.2 (1997): 438–60. * Hernández, Kelly Lytle. "The Crimes and Consequences of Illegal Immigration: A Cross-Border Examination of Operation Wetback, 1943 to 1954," ''Western Historical Quarterly'', 37 (Winter 2006), 421–44. * Kemp, Paul. ''Goodbye Canada?'' (2003), from Canada to U.S. * Khadria, Binod. ''The Migration of Knowledge Workers: Second-Generation Effects of India's Brain Drain'', (2000) * Mullan, Fitzhugh

"The Metrics of the Physician Brain Drain."

''New England Journal of Medicine'', Volume 353:1810–18 October 27, 2005 Number 17 * Odem, Mary and William Brown

Living Across Borders: Guatemala Migrants in the U.S. South

''Southern Spaces'', 2011. * Palmer, Ransford W

''In Search of a Better Life: Perspectives on Migration from the Caribbean''

Praeger, 1990. * Skeldon, Ronald, and Wang Gungwu

''Reluctant Exiles? Migration from Hong Kong and the New Overseas Chinese''

1994. * Smith, Michael Peter, and Adrian Favell. ''The Human Face of Global Mobility: International Highly Skilled Migration in Europe, North America and the Asia-Pacific'', (2006) * Wong, Tom K. ''The politics of immigration: Partisanship, demographic change, and American national identity'' (Oxford UP, 2017).

Emigration Across the Atlantic: Irish, Italians and Swedes compared, 1800–1950

''Distant Magnets: Expectations and Realities in the Immigrant Experience, 1840–1930''

1993. 312 pp * Hourwich, Isaac

''Immigration and Labor: The Economic Aspects of European Immigration to the United States''

(1912), argues immigrants were beneficial to natives by pushing them upward * Hutchinson, Edward P. ''Legislative history of American immigration policy, 1798–1965'' (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). * Jenks, Jeremiah W. and W. Jett Lauck

''The Immigrant Problem''

(1912; 6th ed. 1926) based on 1911 Immigration Commission report, with additional data * Kulikoff, Allan; ''From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers'' (2000), details on colonial immigration * LeMay, Michael, and Elliott Robert Barkan

''U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Issues: A Documentary History''

(1999) * Miller, Kerby M. ''Emigrants and Exiles'' (1985), influential scholarly interpretation of Irish immigration * Motomura, Hiroshi. ''Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States'' (2006), legal history * Wittke, Carl

''We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant''

(1939), 552 pp good older history that covers major groups

online

* Archdeacon, Thomas J. "Problems and Possibilities in the Study of American Immigration and Ethnic History", ''International Migration Review'' Vol. 19, No. 1 (Spring, 1985), pp. 112–3

in JSTOR

* Diner, Hasia. "American Immigration and Ethnic History: Moving the Field Forward, Staying the Course", ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' 25#4 (2006), pp. 130–41 * Gabaccia, Donna. "Immigrant Women: Nowhere at Home?" ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' Vol. 10, No. 4 (Summer, 1991), pp. 61–8

in JSTOR

* Gabaccia, Donna R. "Do We Still Need Immigration History?", ''Polish American Studies'' Vol. 55, No. 1 (Spring, 1998), pp. 45–6

in JSTOR

* Gerber, David A. “Immigration Historiography at the Crossroads.” ''Reviews in American History,'' 39#1 (2011), pp. 74–86

online

* Gerber, David A. "What's Wrong with Immigration History?" ''Reviews in American History'' v 36 (December 2008): 543–56. * Gerber, David, and Alan Kraut, eds. ''American immigration and ethnicity: a reader'' (Springer, 2016), escerpts from scholar

excerpts

* Gjerde, Jon. "New Growth on Old Vines – The State of the Field: The Social History of Ethnicity and Immigration in the United States", ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' 18 (Summer 1999): 40–65

in JSTOR

* Harzig, Christiane, and Dirk Hoerder. ''What is Migration History'' (2009

excerpt and text search

* Hollifield, James F. "American Immigration Politics: An Unending Controversy." ''Revue europeenne des migrations internationales'' 32.3 et 4 (2016): 271–96

online

* Joranger, Terje, and Mikael Hasle. "A Historiographical Perspective on the Social History of Immigration to and Ethnicity in the United States", '' Swedish-American Historical Quarterly'', (2009) 60#1, pp. 5–24 * Jung, Moon-Ho. "Beyond These Mythical Shores: Asian American History and the Study of Race", ''History Compass'', (2008) 6#2 pp. 627–38 * Kazal, Russell A. "Revisiting Assimilation: The Rise, Fall, and Reappraisal of a Concept in American Ethnic History", ''American Historical Review'' (1995) 100#2, pp. 437–7

in JSTOR

* Kenny, Kevin. "Twenty Years of Irish American Historiography", ''Journal of American Ethnic History'', (2009), 28#4 pp. 67–75 * Lederhendler, Eli. "The New Filiopietism, or Toward a New History of Jewish Immigration to America", ''American Jewish History'', (2007) 93#1 pp. 1–20 * Lee, Erika. "A part and apart: Asian American and immigration history." ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' 34.4 (2015): 28–42

online

* Meagher, Timothy J. "From the World to the Village and the Beginning to the End and After: Research Opportunities in Irish American History", ''Journal of American Ethnic History'', Summer 2009, Vol. 28 Issue 4, pp. 118–3

in JSTOR

* Obinna, Denise N. "Lessons in Democracy: America's Tenuous History with Immigrants." ''Journal of Historical Sociology'' 31.3 (2018): 238-252

online

* Persons, Stow. ''Ethnic Studies in Chicago, 1905–1945'' (1987), on Chicago school of sociology * * Ross, Dorothy. ''

* * Stolarik, M. Mark. "From Field to Factory: The Historiography of Slovak Immigration to the United States", ''International Migration Review'', Spring 1976, Vol. 10 Issue 1, pp. 81–10

in JSTOR

* * Vecoli, Rudolph J. "Contadini in Chicago: A Critique of The Uprooted", ''Journal of American History'' 5 (December 1964): 404–17, critique of Handli

in JSTOR

* Vecoli, Rudolph J. "'Over the Years I Have Encountered the Hazards and Rewards that Await the Historian of Immigration,' George M. Stephenson and the Swedish American Community", ''Swedish American Historical Quarterly'' 51 (April 2000): 130–49. * Weinberg, Sydney Stahl, et al. "The Treatment of Women in Immigration History: A Call for Change" ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' 11#4 (Summer, 1992), pp. 25–6

in JSTOR

* Yans-McLaughlin, Virginia ed. ''Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics'' (1990)

(1911) complete set of reports *

''Abstracts of Reports,''

2 vols. (1911); summary of the full 42-volume report; see also Jenks and Lauck *

''Reports of the Immigration Commission: Statements''

(1911) text of statements pro and con

Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey: English translations of 120,000 pages of newspaper articles from Chicago's foreign language press from 1855 to 1938.

{{Immigration to the United States Articles containing video clips History of the United States by topic

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, from the colonial era to the present. The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

experienced successive waves of immigration, particularly from Europe, and later from Asia and Latin America. Colonial era immigrants often repaid the cost of transoceanic transportation by becoming indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

where the new employer paid the ship's captain. Starting in the late 19th century, immigration was restricted from China and Japan. In the 1920s, restrictive immigration quotas were imposed, although political refugees had special status. Numerical restrictions ended in 1965. In recent years, the largest numbers have come from Asia and Central America.

Attitudes towards new immigrants have cycled between favorable and hostile since the 1790s. Recent debates focus on the Southern border, and on the status of "dreamers" who have lived almost their entire life in the U.S. after being brought in without papers as children.

Colonial era

In 1607, the first successful English colony settled inJamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James (Powhatan) River about southwest of the center of modern Williamsburg. It was ...

. Once tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

was found to be a profitable cash crop

A cash crop or profit crop is an agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") in subsist ...

, many plantations were established along the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

.

Thus began the first and longest era of immigration, lasting until the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

in 1775; during this time settlements grew from initial English toe-holds from the New World to British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas fro ...

. It brought Northern European immigrants, primarily of British, German, and Dutch extraction. The British ruled from the mid-17th century and they were by far the largest group of arrivals, remaining within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Over 90% of these early immigrants became farmers.

Large numbers of young men and women came alone as indentured servants. Their passage was paid by employers in the colonies who needed help on the farms or in shops. Indentured servants were provided food, housing, clothing and training but they did not receive wages. At the end of the indenture (usually around age 21, or after a service of seven years) they were free to marry and start their own farms.

New England

Seeking religious freedom in the New World, one hundred English Pilgrims established a small settlement nearPlymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth (; historically known as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklore, and culture, and is known ...

in 1620. Tens of thousands of English Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

arrived, mostly from the East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

n parts of England (Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

, East Sussex

East Sussex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England on the English Channel coast. It is bordered by Kent to the north and east, West Sussex to the west, and Surrey to the north-west. The largest settlement in East ...

., and settled in Boston, Massachusetts and adjacent areas from around 1629 to 1640 to create a land dedicated to their religion. The earliest New English colonies, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

, and New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, were established along the northeast coast. Large scale immigration to this region ended before 1700, though a small but steady trickle of later arrivals continued.

The New English colonists were the most urban and educated of all their contemporaries, and they had many skilled farmers, tradesmen and craftsmen among them. They started the first university

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

, Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, in 1635 in order to train their ministers. They mostly settled in small villages for mutual support (nearly all of them had their own militias) and common religious activities. Shipbuilding, commerce, agriculture, and fishing were their main sources of income. New England's healthy climate (the cold winters killed the mosquitoes and other disease-bearing insects), small widespread villages (minimizing the spread of disease), and an abundant food supply resulted in the lowest death rate and the highest birth rate of any of the colonies. The Eastern and Northern frontier around the initial New England settlements was mainly settled by the descendants of the original New Englanders. Immigration to the New England colonies after 1640 and the start of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

decreased to less than 1% (about equal to the death rate) in nearly all of the years prior to 1845. The rapid growth of the New England colonies (approximately 900,000 by 1790) was almost entirely due to the high birth rate (>3%) and the low death rate (<1%) per year.

Dutch

The Dutch colonies, organized by the United East Indian Company, were first established along theHudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

in present-day New York state starting about 1626. Wealthy Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

patroons set up large landed estates along the Hudson River and brought in farmers who became renters. Others established rich trading posts to trade with Native Americans and started cities such as New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

(now New York City) and Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

. After the British seized the colony and renamed it New York, Germans (from the Palatinate) and Yankees (from New England) began arriving.

Middle colonies

Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware formed the middle colonies. Pennsylvania was settled byQuakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

from Britain, followed by Ulster Scots (Northern Ireland) on the frontier and numerous German Protestant sects, including the German Palatines

Palatines (german: Pfälzer), also known as the Palatine Dutch, are the people and princes of Palatinates ( Holy Roman principalities) of the Holy Roman Empire. The Palatine diaspora includes the Pennsylvania Dutch and New York Dutch.

In 1709 ...

. The earlier colony of New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden f ...

had small settlements on the lower Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, before ...

, with immigrants of Swedes

Swedes ( sv, svenskar) are a North Germanic ethnic group native to the Nordic region, primarily their nation state of Sweden, who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countr ...

and Finns

Finns or Finnish people ( fi, suomalaiset, ) are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these ...

. These colonies were absorbed by 1676.

The middle colonies were scattered west of New York City (established 1626; taken over by the English in 1664) and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (established 1682). New Amsterdam/New York had the most diverse residents from different nations and prospered as a major trading and commercial center after about 1700. From around 1680 to 1725, Pennsylvania was controlled by the Quakers. The commercial center of Philadelphia was run mostly by prosperous Quakers, supplemented by many small farming and trading communities, with a strong German contingent located in villages in the Delaware River valley.

Starting around 1680, when Pennsylvania was founded, many more settlers arrived to the middle colonies. Many Protestant sects were attracted by freedom of religion and good, cheap land. They were about 60% British and 33% German. By 1780, New York's population were around 27% descendants of Dutch settlers, about 6% were African, and the remainder were mostly English with a wide mixture of other Europeans. New Jersey, and Delaware had a British majority, with 7–11% German-descendants, about 6% African population, and a small contingent of the Swedish descendants of New Sweden.

Frontier

The fourth major center of settlement was the western frontier, located in the inland parts of Pennsylvania and south colonies. It was mainly settled from about 1717 to 1775 byPresbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

farmers from North England border lands, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

, fleeing hard times and religious persecution. Between 250,000 and 400,000 Scots-Irish migrated to America in the 18th century. The Scots-Irish soon became the dominant culture of the Appalachians from Pennsylvania to Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Areas where 20th century censuses reported mostly 'American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

' ancestry were the places where, historically, northern English, Scottish and Scots-Irish Protestants settled: in the interior of the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, and the Appalachian region. Scots-Irish American immigrants, were made up of people from the southernmost counties of Scotland who had initially settled in Ireland. They were heavily Presbyterian, and largely self-sufficient. The Scots-Irish arrived in large numbers during the early 18th century and they often preferred to settle in the back country and the frontier from Pennsylvania to Georgia, where they mingled with second generation and later English settlers. They enjoyed the very cheap land and independence from established governments common to frontier settlements.

Southern colonies

The mostly agricultural Southern English colonies initially had very high death rates for new settlers due tomalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

, and other diseases as well as skirmishes with Native Americans. Despite this, a steady flow of new immigrants, mostly from Central England and the London area, kept up population growth. As early as 1630, initial areas of settlement had been largely cleared of Native Americans by major outbreaks of measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, and bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

beginning already decades before European settlers began arriving in large numbers. The leading killer was smallpox, which arrived in the New World around 1510–1530.

Initially, the plantations established in these colonies were mostly owned by friends (mostly minor aristocrats and gentry) of the British-appointed governors. A group of Gaelic-speaking Scottish Highlanders created a settlement at Cape Fear in North Carolina, which remained culturally distinct until the mid-18th century, at which point it was swallowed up by the dominant English-origin culture. Many settlers from Europe arrived as indentured servants, having had their passage paid for, in return for five to seven years of work, including free room and board, clothing, and training, but without cash wages. After their periods of indenture expired, many of these former servants founded small farms on the frontier.

By the early 18th century, the involuntary migration of African slaves was a significant component of the immigrant population in the Southern colonies. Between 1700 and 1740, a large majority of the net overseas migration to these colonies were Africans. In the third quarter of the 18th century, the population of that region amounted to roughly 55% British, 38% black, and 7% German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

. In 1790, 42% of the population in South Carolina and Georgia was of African origin. Before 1800, the growing of tobacco, rice and indigo in plantations in the Southern colonies relied heavily on the labor of slaves from Africa. The Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

to mainland North America stopped during the Revolution and was outlawed in most states by 1800 and the entire nation in 1808 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (, enacted March 2, 1807) is a United States federal law that provided that no new slaves were permitted to be imported into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest da ...

, although some slaves continued to be smuggled in illegally.

Characteristics

While the thirteen colonies differed in how they were settled and by whom, they had many similarities. Nearly all were settled and financed by privately organized British settlers or families using free enterprise without any significant Royal or Parliamentary government support. Nearly all commercial activity comprised small, privately owned businesses with good credit both in America and in England, which was essential since they were often cash poor. Most settlements were largely independent of British trade, since they grew or manufactured nearly everything they needed; the average cost of imports per household was 5–15pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

per year. Most settlements consisted of complete family groups with several generations present. The population was rural, with close to 80% owning the land on which they lived and farmed. After 1700, as the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

progressed, more of the population started to move to cities, as had happened in Britain. Initially, the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

settlers spoke languages brought over from Europe, but English was the main language of commerce. Governments and laws mainly copied English models. The only major British institution to be abandoned was the aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

, which was almost totally absent. The settlers generally established their own law-courts and popularly elected governments. This self-ruling pattern became so ingrained that for the next 200 years almost all new settlements had their own government up and running shortly after arrival.

After the colonies were established, their population growth comprised almost entirely organic growth, with foreign-born immigrant populations rarely exceeding 10%. The last significant colonies to be settled primarily by immigrants were Pennsylvania (post-1680s), the Carolinas (post-1663), and Georgia (post-1732). Even here, the immigrants came mostly from England and Scotland, with the exception of Pennsylvania's large Germanic contingent. Elsewhere, internal American migration from other colonies provided nearly all of the settlers for each new colony or state. Populations grew by about 80% over a 20-year period, at a "natural" annual growth rate of 3%.

Over half of all new British immigrants in the South initially arrived as indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

, mostly poor young people who could not find work in England nor afford passage to America. In addition, about 60,000 British convicts guilty of minor offences were transported to the British colonies in the 18th century, with the "serious" criminals generally having been executed. Ironically, these convicts are often the only immigrants with nearly complete immigration records, as other immigrants typically arrived with few or no records.

Other colonies

Spanish

AlthoughSpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

set up a few forts in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

, notably San Agustín (present-day Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

) in 1565, they sent few settlers to Florida. Spaniards moving north from Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

founded the San Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John, may refer to:

Places Argentina

* San Juan Province, Argentina

* San Juan, Argentina, the capital of that province

* San Juan, Salta, a village in Iruya, Salta Province

* San Juan (Buenos Aires Underground), ...

on the Rio Grande in 1598 and Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe ( ; , Spanish for 'Holy Faith'; tew, Oghá P'o'oge, Tewa for 'white shell water place'; tiw, Hulp'ó'ona, label= Northern Tiwa; nv, Yootó, Navajo for 'bead + water place') is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. The name “S ...

in 1607–1608. The settlers were forced to leave temporarily for 12 years (1680–1692) by the Pueblo Revolt

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, also known as Popé's Rebellion or Popay's Rebellion, was an uprising of most of the indigenous Pueblo people against the Spanish colonizers in the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, larger than present-day New Mex ...

before returning.

Spanish Texas

Spanish Texas was one of the interior provinces of the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1690 until 1821. The term "interior provinces" first appeared in 1712, as an expression meaning "far away" provinces. It was only in 1776 that a leg ...

lasted from 1690 to 1821, when Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

was governed as a colony that was separate from New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

. In 1731, Canary Islanders

Canary Islanders, or Canarians ( es, canarios), are a Romance people and ethnic group. They reside on the Canary Islands, an autonomous community of Spain near the coast of northwest Africa, and descend from a mixture of European settlers and a ...

(or "Isleños") arrived to establish San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

. The majority of the few hundred Texan and New Mexican colonizers in the Spanish colonial period were Spaniards and criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

. California, New Mexico and Arizona all had Spanish settlements. In 1781, Spanish settlers founded Los Angeles.

At the time the former Spanish colonies joined the United States, Californios

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sinc ...

in California numbered about 10,000 and Tejanos

Tejanos (, ; singular: ''Tejano/a''; Spanish for "Texan", originally borrowed from the Caddo ''tayshas'') are the residents of the state of Texas who are culturally descended from the Mexican population of Tejas and Coahuila that lived in th ...

in Texas about 4,000. New Mexico had 47,000 Spanish settlers in 1842; Arizona was only thinly settled.

However, not all these settlers were of European descent. As in the rest of the American colonies, new settlements were based on the casta

() is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas it also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical f ...

system, and although all could speak Spanish, it was a melting pot of whites, natives, and mestizos.

French

In the late 17th century, French expeditions established a foothold on theSaint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

, Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

and Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

. Interior trading posts, forts and cities were thinly spread. The city of Detroit was the third-largest settlement in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

. expanded when several thousand French-speaking refugees from the region of Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

made their way to Louisiana following British expulsion, settling largely in the Southwest Louisiana region now called Acadiana

Acadiana (French and Louisiana French: ''L'Acadiane''), also known as the Cajun Country ( Louisiana French: ''Le Pays Cadjin'', es, País Cajún), is the official name given to the French Louisiana region that has historically contained ...

. Their descendants are now called Cajun

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

While Cajuns are usually described as ...

and still dominate the coastal areas. About 7,000 French-speaking immigrants settled in Louisiana during the 18th century.

Population in 1790

The following were the countries of origin for new arrivals to the United States before 1790. The regions marked with an asterisk were part of Great Britain. The ancestry of the 3.9 million population in 1790 has been estimated by various sources by sampling last names from the 1790 census and assigning them a country of origin. The Irish in the 1790 census were mostly Scots-Irish. The French were primarilyHuguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster B ...

. The total U.S. Catholic population in 1790 was probably less than 5%. The Native American population inside territorial U.S. boundaries was less than 100,000.

The 1790 population reflected the loss of approximately 46,000 Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

, or "Tories", who immigrated to Canada at the end of the American Revolution, 10,000 who went to England and 6,000 to the Caribbean.

The 1790 census recorded 3.9 million inhabitants (not counting American Indians). Of the total white population of just under 3.2 million in 1790, approximately 86% was of British ancestry (60%, or 1.9 million, English, 4.3% Welsh, 5.4% Scots, 5.8% Irish (South), and 10.5% Scots-Irish. Among those whose ancestry was from outside of British Isles, Germans were 9%, Dutch 3.4%, French 2.1%, and Swedish 0.25%; blacks made up 19.3% (or 762,000) of the U.S. population. The number of Scots was 200,000; Irish and Scot-Irish 625,000. The overwhelming majority of Southern Irish were Protestant, as there were only 60,000 Catholics in the United States in 1790, 1.6% of the population. Many U.S. Catholics were descendants of English Catholic settlers in the 17th century; the rest were Irish, German and some Acadians who remained. In this era, the population roughly doubled every 23 years, mostly due to natural increase. Relentless population expansion pushed the U.S. frontier to the Pacific by 1848. Most immigrants came long distances to settle in the United States. However, many Irish left Canada for the United States in the 1840s. French Canadians

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

who moved south from Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

after 1860, and the Mexicans

Mexicans ( es, mexicanos) are the citizens of the United Mexican States.

The most spoken language by Mexicans is Spanish, but some may also speak languages from 68 different Indigenous linguistic groups and other languages brought to Mexi ...

who came north after 1911, found it easier to move back and forth.

1790 to 1860s

If one excludes enslaved Africans, there was relatively little immigration from 1770 to 1830; while there was significant emigration from the U.S. to Canada, including about 75,000 Loyalists as well as Germans and others looking for better farmland in what is now Ontario. Large-scale immigration in the 1830s to 1850s came from Britain, Ireland, Germany. Most were attracted by the cheap farmland. Some were artisans and skilled factory workers attracted by the first stage of industrialization. The Irish Catholics were primarily unskilled workers who built a majority of the canals and railroads, settling in urban areas. Many Irish went to the emerging textile mill towns of the Northeast, while others became longshoremen in the growing Atlantic and Gulf port cities. Half the Germans headed to farms, especially in the Midwest (with some to Texas), while the other half became craftsmen in urban areas. Nativism took the form of political anti-Catholicism directed mostly at the Irish (as well as Germans). It became important briefly in the mid-1850s in the guise of theKnow Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

party. Most of the Catholics and German Lutherans became Democrats, and most of the other Protestants joined the new Republican Party. During the Civil War, ethnic communities supported the war and produced large numbers of soldiers on both sides. Riots

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targeted ...

broke out in New York City and other Irish and German strongholds in 1863 when a draft was instituted, particularly in light of the provision exempting those who could afford payment.

Immigration totaled 8,385 in 1820, with immigration totals gradually increasing to 23,322 by the year 1830; for the 1820s decade immigration more than doubled to 143,000. Between 1831 and 1840, immigration more than quadrupled to a total of 599,000. These included about 207,000 Irish, starting to emigrate in large numbers following Britain's easing of travel restrictions, and about 152,000 Germans, 76,000 British, and 46,000 French, constituting the next largest immigrant groups of the decade.

Between 1841 and 1850, immigration nearly tripled again, totaling 1,713,000 immigrants, including at least 781,000 Irish, 435,000 Germans, 267,000 British, and 77,000 French. The Irish, driven by the Great Famine (1845–1849), emigrated directly from their homeland to escape poverty and death. The failed revolutions of 1848 brought many intellectuals and activists to exile in the U.S. Bad times and poor conditions in Europe drove people out, while land, relatives, freedom, opportunity, and jobs in the US lured them in.

Starting in 1820, some federal records, including ship passenger lists, were kept for immigration purposes, and a gradual increase in immigration was recorded; more complete immigration records provide data on immigration after 1830. Though conducted since 1790, the census of 1850 was the first in which place of birth was asked specifically. The foreign-born population in the U.S. likely reached its minimum around 1815, at approximately 100,000 or 1% of the population. By 1815, most of the immigrants who arrived before the American Revolution had died, and there had been almost no new immigration thereafter.

Nearly all population growth up to 1830 was by internal increase; around 98% of the population was native-born. By 1850, this shifted to about 90% native-born. The first significant Catholic immigration started in the mid-1840s, shifting the population from about 95% Protestant down to about 90% by 1850.

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, concluding the Mexican War, extended U.S. citizenship to approximately 60,000 Mexican residents of the New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomin ...

and 10,000 living in Mexican California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

. An additional approximate 2,500 foreign-born California residents also became U.S. citizens.

In 1849, the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

attracted 100,000 would-be miners from the Eastern U.S., Latin America, China, Australia, and Europe. California became a state in 1850 with a population of about 90,000.

1850 to 1930

Demography

Between 1850 and 1930, about 5 million Germans migrated to the United States, peaking between 1881 and 1885 when a million Germans settled primarily in theMidwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. Between 1820 and 1930, 3.5 million British and 4.5 million Irish entered America. Before 1845, most Irish immigrants were Protestants. After 1845, Irish Catholics began arriving in large numbers, largely driven by the Great Famine.

After 1880, larger steam-powered oceangoing ships replaced sailing ships, which resulted in lower fares and greater immigrant mobility. In addition, the expansion of a railroad system in Europe made it easier for people to reach oceanic ports to board ships. Meanwhile, farming improvements in Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alb ...

and the Russian Empire created surplus labor. Young people between the ages of 15 to 30 were predominant among newcomers. This wave of migration, constituting the third episode in the history of U.S. immigration, may be better referred to as a flood of immigrants, as nearly 25 million Europeans made the long trip. Italians, Greeks, Hungarians, Poles, and others speaking Slavic languages made up the bulk of this migration. 2.5 to 4 million Jews were among them.

Destinations

Each group evinced a distinctive migration pattern in terms of the gender balance within the migratory pool, the permanence of their migration, their literacy rates, the balance between adults and children, and the like. But they shared one overarching characteristic: they flocked to urban destinations and made up the bulk of the U.S. industrial labor pool, making possible the emergence of such industries as steel, coal, automotive, textile, and garment production, enabling the United States to leap into the front ranks of the world's economic giants. Their urban destinations, numbers, and perhaps an antipathy towards foreigners, led to the emergence of the second wave of organized xenophobia. By the 1890s, many Americans, particularly from the ranks of the well-off, white, and native-born, considered immigration to pose a serious danger to the nation's health and security. In 1893 a group formed the Immigration Restriction League, and it, along with other similarly inclined organizations, began to press Congress for severe curtailment of foreign immigration. Irish and German Catholic immigration was opposed in the 1850s by thenativist movement

Nativism is the political policy of promoting or protecting the interests of native or indigenous inhabitants over those of immigrants, including the support of immigration-restriction measures.

In scholarly studies, ''nativism'' is a standard ...

, originating in New York in 1843 as the American Republican Party

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP ("Grand Old Party"), is one of the Two-party system, two Major party, major contemporary political parties in the United States. The GOP was founded in 1854 by Abolitionism in the United Stat ...

(not to be confused with the modern Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

). It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to American values and controlled by the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Active mainly from 1854 to 1856, it strove to curb immigration and naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

, though its efforts met with little success. There were few prominent leaders, and the largely middle-class and Protestant membership fragmented over the issue of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, most often joining the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

by the time of the 1860 presidential election.Welcome to The American PresidencyEuropean immigrants joined the

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

in large numbers, including 177,000 born in Germany and 144,000 born in Ireland, a full 16% of the Union Army. Many Germans could see the parallels between slavery and serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

in the old fatherland.

Between 1840 and 1930, about 900,000 French Canadians

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

left Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

in order to immigrate to the United States and work mainly in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. About half returned. Considering the fact that the population of Quebec was only 892,061 in 1851, this was a massive exodus. 13.6 million Americans claimed to have French ancestry in the 1980 census. A large portion of them have ancestors who emigrated from French Canada

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

, since immigration from France was low throughout the history of the United States. The communities established by these immigrants became known as Little Canada.

Shortly after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, some states started to pass their own immigration laws, which prompted the U.S. Supreme Court to rule in 1875 that immigration was a federal responsibility.

In 1875, the nation passed its first immigration law, the Page Act of 1875

The Page Act of 1875 (Sect. 141, 18 Stat. 477, 3 March 1875) was the first restrictive federal immigration law in the United States, which effectively prohibited the entry of Chinese women, marking the end of open borders. Seven years later, th ...

, also known as the Asian Exclusion Act, outlawing the importation of Asian contract laborers, any Asian woman who would engage in prostitution, and all people considered to be convicts in their own countries.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

. By excluding all Chinese laborers from entering the country, the Chinese Exclusion Act severely curtailed the number of immigrants of Chinese descent allowed into the United States for 10 years. The law was renewed in 1892 and 1902. During this period, Chinese migrants illegally entered the United States through the loosely guarded U.S.–Canadian border. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed with the passage of the Magnuson Act in 1943.

Prior to 1890, the individual states, rather than the Federal government, regulated immigration into the United States. The Immigration Act of 1891 established a Commissioner of Immigration in the Treasury Department. The

Prior to 1890, the individual states, rather than the Federal government, regulated immigration into the United States. The Immigration Act of 1891 established a Commissioner of Immigration in the Treasury Department. The Canadian Agreement The Canadian Agreement was an 1894 agreement between the United States and signatory transportation companies that prohibited transportation companies from landing immigrants who were barred from entry in the U.S. into Canadian ports.

Background

Du ...

of 1894 extended U.S. immigration restrictions to Canadian ports.

The

The Dillingham Commission

The United States Immigration Commission (also known as the Dillingham Commission after its chairman, Republican Senator William P. Dillingham of Vermont) was a bipartisan special committee formed in February 1907 by the United States Congress, P ...

was set up by Congress in 1907 to investigate the effects of immigration on the country. The Commission's 40-volume analysis of immigration during the previous three decades led it to conclude that the major source of immigration had shifted from Central, Northern, and Western Europeans to Southern Europeans and Russians. It was, however, apt to make generalizations about regional groups that were subjective and failed to differentiate between distinct cultural attributes.

The 1910s marked the high point of Italian immigration to the United States. Over two million Italians immigrated in those years, with a total of 5.3 million between 1880 and 1920. About half returned to Italy, after working an average of five years in the U.S.

About 1.5 million Swedes and Norwegians immigrated to the United States within this period, due to opportunity in America and poverty and religious oppression in united Sweden–Norway

Sweden and Norway or Sweden–Norway ( sv, Svensk-norska unionen; no, Den svensk-norske union(en)), officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, and known as the United Kingdoms, was a personal union of the separate kingdoms of Sweden ...

. This accounted for around 20% of the total population of the kingdom at that time. They settled mainly in the Midwest, especially Minnesota and the Dakotas. Danes had comparably low immigration rates due to a better economy; after 1900 many Danish immigrants were Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into se ...

converts who moved to Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

.

Over two million

Over two million Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

ans, mainly Catholics and Jews, immigrated between 1880 and 1924. People of Polish ancestry are the largest Central European ancestry group in the United States after Germans. Immigration of Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

ethnic groups was much lower.

Lebanese and Syrian

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

immigrants started to settle in large numbers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The vast majority of the immigrants from Lebanon and Syria were Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ� ...

, but smaller numbers of Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, and Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

also settled. Many lived in New York City's Little Syria

Little Syria ( ar, سوريا الصغيرة) was a diverse neighborhood that existed in the New York City borough of Manhattan from the late 1880s until the 1940s., pp.76-77; Two other sections of New York were singled out as particularly Syrian ...

and in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. In the 1920s and 1930s, a large number of these immigrants set out West, with Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

getting a large number of Middle Eastern immigrants, as well as many Midwestern areas where the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

worked as farmers.

Congress passed a literacy requirement in 1917 to curb the influx of low-skilled immigrants from entering the country.

Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the larg ...

in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

, which supplanted earlier acts to effectively ban all immigration from Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

and set quotas for the Eastern Hemisphere so that no more than 2% of nationalities as represented in the 1890 census were allowed to immigrate to America.

New Immigration

"New immigration" was a term from the late 1880s that refers to the influx of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (areas that previously sent few immigrants). The great majority came through

"New immigration" was a term from the late 1880s that refers to the influx of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (areas that previously sent few immigrants). The great majority came through Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mil ...

in New York, thus making the Northeast a major target of settlement. However there were a few efforts, such as the Galveston Movement, to redirect immigrants to other ports and disperse some of the settlement to other areas of the country.

Nativists feared the new arrivals lacked the political, social, and occupational skills needed to successfully assimilate into American culture. This raised the issue of whether the U.S. was still a "melting pot

The melting pot is a monocultural metaphor for a heterogeneous society becoming more homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative being a homogeneous society becoming more heterogeneous throu ...

", or if it had just become a "dumping ground", and many old-stock Americans worried about negative effects on the economy, politics, and culture. A major proposal was to impose a literacy test, whereby applicants had to be able to read and write in their own language before they were admitted. In Southern and Eastern Europe, literacy was low because the governments did not invest in schools.

1920 to 2000

Restriction proceeded piecemeal over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but immediately after the end of World War I (1914–1918) and into the early 1920s, Congress changed the nation's basic policy about immigration. TheNational Origins Formula

National Origins Formula is an umbrella term for a series of qualitative immigration quotas in America used from 1921 to 1965, which restricted immigration from the Eastern Hemisphere on the basis of national origin. These restrictions included l ...

of 1921 (and its final form in 1924) not only restricted the number of immigrants who might enter the United States but also assigned slots according to quotas based on national origins. The bill was so limiting that the number of immigrants coming to the U.S. between 1921 and 1922 decreased by nearly 500,000. A complicated piece of legislation, it essentially gave preference to immigrants from Central, Northern, and Western Europe, limiting the numbers from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, and gave zero quotas to Asia. However close family members could come.

The legislation excluded Latin America from the quota system. Immigrants could and did move quite freely from Mexico, the Caribbean (including Jamaica, Barbados, and Haiti), and other parts of Central and South America.

The era of the 1924 legislation lasted until 1965. During those 40 years, the United States began to admit, case by case, limited numbers of refugees. Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

before World War II, Jewish Holocaust survivors after the war, non-Jewish displaced persons fleeing communist rule in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, Hungarians seeking refuge after their failed uprising in 1956, and Cubans after the 1959 revolution managed to find haven in the United States when their plight moved the collective conscience of America, but the basic immigration law remained in place.

Equal Nationality Act of 1934

This law allowed foreign-born children of American mothers andalien

Alien primarily refers to:

* Alien (law), a person in a country who is not a national of that country

** Enemy alien, the above in times of war

* Extraterrestrial life, life which does not originate from Earth

** Specifically, intelligent extrater ...

fathers who had entered America before the age of 18 and had lived in America for five years to apply for American citizenship for the first time. It also made the naturalization process quicker for the alien husbands of American wives. This law equalized expatriation, immigration, naturalization, and repatriation between women and men. However, it was not applied retroactively, and was modified by later laws, such as the Nationality Act of 1940.

Filipino immigration

In 1934, theTydings–McDuffie Act

The Tydings–McDuffie Act, officially the Philippine Independence Act (), is an Act of Congress that established the process for the Philippines, then an American territory, to become an independent country after a ten-year transition period. ...

provided independence of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

on July 4, 1946. Until 1965, national origin quotas strictly limited immigration from the Philippines. In 1965, after revision of the immigration law, significant Filipino immigration began, totaling 1,728,000 by 2004.

Postwar immigration