The present day

Republic of Tunisia, ''al-Jumhuriyyah at-Tunisiyyah'', is situated in Northern Africa. Geographically situated between

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

to the east,

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

to the west and the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to the north.

Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

is the capital and the largest city (population over 800,000); it is near the ancient site of the city of

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

.

Throughout its recorded history, the physical features and environment of the land of Tunisia have remained fairly constant, although during ancient times more abundant forests grew in the north, and earlier in prehistory the

Sahara to the south was not an arid desert.

The weather is temperate in the north, which enjoys a

Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

with mild rainy winters and hot dry summers, the terrain being wooded and fertile. The

Medjerda river valley (Wadi Majardah, northeast of Tunis) is currently valuable farmland. Along the eastern coast the central plains enjoy a moderate climate with less rainfall but significant precipitation in the form of heavy dews; these coastlands are currently used for orchards and grazing. Near the mountainous Algerian border rises ''

Jebel ech Chambi'', the highest point in the country at 1544 meters. In the near south, a belt of

salt lakes running east–west cuts across the country. Further south lies the

Sahara desert, including the sand dunes of the ''

Grand Erg Oriental

The Grand Erg Oriental (English: 'Great Eastern Sand Sea') is a large ''erg'' or "field of sand dunes" in the Sahara Desert. Situated for the most part in Saharan lowlands of northeast Algeria, the Grand Erg Oriental covers an area some 600 k ...

''.

[''The World Factbook'' on "Tunisia"](_blank)

Early history

First peoples

Stone age tools dating from the

Middle Stone Age (around 200,000 years ago) found near

Kelibia

Kelibia (Kélibia) ( ar, قليبية, link=no '), often referred to as Klibia or Gallipia by European writers, is a coastal town on the Cap Bon peninsula, Nabeul Governorate in the far north-eastern part of Tunisia. Its sand beaches are consider ...

are the earliest evidence of human activity in the region. Finds have been made of stone blades, tools, and small figurines of the

Capsian culture

The Capsian culture was a Mesolithic and Neolithic culture centered in the Maghreb that lasted from about 8,000 to 2,700 BC. It was named after the town of Gafsa in Tunisia, which was known as Capsa in Roman times.

Capsian industry was concen ...

(named after

Gafsa

Gafsa ( aeb, ڨفصة '; ar, قفصة qafṣah), originally called Capsa in Latin, is the capital of Gafsa Governorate of Tunisia. It lends its Latin name to the Mesolithic Capsian culture. With a population of 111,170, Gafsa is the ninth-la ...

in Tunisia), which lasted from around 10,000 to 6,000 BC (the

Mesolithic period). Seasonal migration routes evidence their ancient journeys.

Saharan rock art

Saharan rock art is a significant area of archaeological study focusing on artwork carved or painted on the natural rocks of the central Sahara desert. The rock art dates from numerous periods starting years ago, and is significant because it sh ...

, consisting of inscriptions and paintings that show design patterns as well as figures of animals and of humans, are attributed to the Berbers and also to black Africans from the south. Dating these outdoor art works has proven difficult and unsatisfactory. Egyptian influence is thought very unlikely. Among the animals depicted, alone or in staged scenes, are large-horned buffalo (the extinct ''

bubalus antiquus''), elephants, donkeys, colts, rams, herds of cattle, a lion and lioness with three cubs, leopards or cheetahs, hogs, jackals, rhinoceroses, giraffes, hippopotamus, a hunting dog, and various antelope. Human hunters may wear animal masks and carry their weapons. Herders are shown with elaborate head ornamentation; a few other human figures are shown dancing, while others are driving chariots or riding camels.

By five thousand years ago, a

neolithic culture was evolving among the sedentary proto-Berbers of the

Maghrib

The Maghrib Prayer ( ar, صلاة المغرب ', "sunset prayer") is one of the five mandatory salah (Islamic prayer). As an Islamic day starts at sunset, the Maghrib prayer is technically the first prayer of the day. If counted from midni ...

in northwest Africa, characterized by the practice of agriculture and animal domestication, as well as the making of pottery and finely chipped stone arrowheads. They planted wheat, barley, beans and chick peas in their fields, and used ceramic bowls and basins, goblets, plates, and large cooking dishes daily. These were stored by hanging on the walls of their domiciles. Archaeological evidence shows these proto-Berbers were already "farmers with a strong pastoral element in their economy and fairly elaborate cemeteries," well over a thousand years before the

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

arrived to found

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

.

Individual wealth was measured among the nomadic herders of the south by the number of sheep, goats, and cattle a man possessed. Finds of scraps of cloth woven in stripes of different colors indicate that these groups wove fabrics.

The

religion of the ancient Berbers is undocumented and only funerary rites can be reconstructed from archaeological evidence. Burial sites provide an early indication of religious beliefs; almost sixty thousand tombs are located in the

Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

alone, according to the Italian scholar Giacomo Caputo.

[ A more recent tomb, the ''Medracen'' in eastern Algeria, still stands. Built for a Berber king and traditionally assigned to ]Masinissa

Masinissa ( nxm, , ''MSNSN''; ''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ult ...

(r. 202–149 BC), it may have belonged instead to his father Gala (or Gaia). The architecture of the elegant tower tomb of his contemporary Syphax shows Greek or Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

influence. Most other information about Berber religious beliefs comes from later, classical times. The Libyans believed that divine power showed itself in the natural world, and could, for example, inhabit bodies of water or reside in stones, which were objects of worship. Procreative power was symbolized by the bull, the lion, and the ram. Among the proto-Berbers in the area that is now Tunisia, images of fish, often found in mosaics excavated there, were phallic symbols that fended off the evil eye, while sea shells signified the female sex. Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

mentions that Libyans of the Nasamone tribe slept on the graves of their ancestors in order to induce dreams for divination. Libyans sacrificed to the sun and to the moon (Ayyur). Eventually supernatural entities became personalized as gods, perhaps influenced by Egyptian or Punic practice; yet the Berbers seemed to be "drawn more to the sacred than to the gods." Often only a little more than the names of the Berber deities are known, e.g., ''Bonchar'', a leading god. Eventually, Berbero-Libyans came to adopt elements from ancient Egyptian religion. Herodotus writes of the divine oracle sourced in the Egyptian god Ammon

Ammon ( Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in ...

located among the Libyans, at the oasis of Siwa. Later, Berber beliefs influenced the Punic religion of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

, the city-state founded by the Phoenicians.

Egyptian hieroglyphs from the early dynasties also testify to Libyans, the Berbers of the "western desert". First mentioned as the Tehenou during the pre-dynastic reigns of Scorpion II

Scorpion II ( Ancient Egyptian: possibly Selk or Weha), also known as King Scorpion, was a ruler during the Protodynastic Period of Upper Egypt (c. ).

Identity

Name

King Scorpion's name and title are of great dispute in modern Egyptol ...

(c. 3050) and of Narmer (on an ivory cylinder), their appearance is later disclosed in a bas relief of the Fifth Dynasty temple of Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Re") was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2465 – c. 2325 BC). He reigned for about 13 years in the early 25th century BC during the Old Kingdom Period. ...

. Ramses II

Ramesses II ( egy, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded as t ...

(r. 1279–1213) placed Libyan contingents in his army. Tombs of the 13th century BC show paintings of ''Libu'' leaders wearing fine robes, with ostrich feathers in their "dreadlocks", short pointed beards, and tattoos on their shoulders and arms.[ Evidently, Osorkon the Elder (Akheperre setepenamun), a Berber of the Meshwesh tribe, became the first Libyan pharaoh. Several decades later, his nephew Shoshenq I (r. 945–924) became ]Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

of Egypt, and the founder of its Twenty-second Dynasty (945–715). In 926 Shoshenq I (thought to be Shishak of the Bible) successfully campaigned to Jerusalem then ruled by Solomon's heir. For several centuries Egypt was governed by a decentralized system based on the Libyan tribal organization of the Meshwesh. Becoming acculturated, Libyans also served as high priests at Egyptian religious centers. Hence during the classical era of the Mediterranean, all of the Berber peoples of Northwest Africa were often known collectively as Libyans.

Farther west, foreigners knew some Berbers as Gaetulians (who lived in remote areas), and those Bebers more familiar as the Numidians

The Numidians were the Berber population of Numidia (Algeria and in smaller parts of Tunisia and Morocco). The Numidians were one of the earliest Berber tribes to trade with Carthaginian settlers. As Carthage grew, the relationship with the Nu ...

, and as the Mauri or Maurisi (later the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

). These Berber peoples interacted with Phoenicia and Carthage (who also used the name "Libyphoenicians"), and later with Rome. Yet prior to this era of history, sedentary rural Berbers apparently lived in semi-independent farming villages, composed of small tribal units under a local leader. Yet seasonally they might leave to find pasture for their herds and flocks. Modern conjecture is that robust feuding between neighborhood clans kept Berber political organization from rising above the village

A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town (although the word is often used to describe both hamlets and smaller towns), with a population typically ranging from a few hundred ...

level, yet the military threat from the city-state of Carthage would inspire Berber villages to join together in order to marshall large-scale armed forces under a strong leader. Social techniques from the nearby polity of Carthage were adopted and modified for Berber use.[

A bilingual (Punic and Berber) urban inscription of the 2nd century BC from Berber Numidia, specifically from the city of ]Thugga

Dougga or Thugga or TBGG was a Berber, Punic and Roman settlement near present-day Téboursouk in northern Tunisia. The current archaeological site covers . UNESCO qualified Dougga as a World Heritage Site in 1997, believing that it represents " ...

(modern Dougga, Tunisia), indicates a complex city administration, with the Berber title GLD (corresponding to modern Berber ''Aguellid'', or paramount tribal chief) being the ruling municipal office of the city government; this office apparently rotated among the members of leading Berber families.[ Circa 220 BC, in the early light given us by historical accounts, three large kingdoms had arisen among the Berbers of Northwest Africa (west to east): (1) the '']Mauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the part of North Africa west of Numidia, in present-day northern Morocco and northwestern Algeria.

Name

''Mauri'' ...

'' (in modern Morocco) under king Baga; (2) the ''Masaesyli

The Masaesyli were a Berber tribe of western Numidia (present day Algeria) and the main antagonists of the Massylii in eastern Numidia.

During the Second Punic War the Masaesyli initially supported the Roman Republic and were led by Syphax ag ...

'' (in northern Algeria) under Syphax who ruled from two capitals, Siga (near modern Oran) and to the east Cirta

Cirta, also known by various other names in antiquity, was the ancient Berber and Roman settlement which later became Constantine, Algeria.

Cirta was the capital city of the Berber kingdom of Numidia; its strategically important port city ...

(modern Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

); and (3) the ''Massyli The Massylii or Maesulians were a Berber federation in eastern Numidia, which was formed by an amalgamation of smaller tribes during the 4th century BC.Nigel Bagnall, The Punic Wars, p. 270. They were ruled by a king. On their loosely defined wester ...

'' (south of Cirta, west and south of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

) ruled by Gala

Gala may refer to:

Music

* ''Gala'' (album), a 1990 album by the English alternative rock band Lush

*'' Gala – The Collection'', a 2016 album by Sarah Brightman

*GALA Choruses, an association of LGBT choral groups

*''Gala'', a 1986 album by T ...

, father of Masinissa

Masinissa ( nxm, , ''MSNSN''; ''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ult ...

. Later Masinissa would receive full honors befitting an important leader from both Roman and Hellenic states.[ Berber ethnic identities were maintained during the long periods of dominance by Carthage and Rome.

During the first centuries of the Islamic era, it was said that the Berber tribes were divided into two blocs, the Butr (Zanata and allies) and the Baranis (Sanhaja, Masmuda, and others).]etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

of these names is unclear, perhaps deriving from tribal customs for clothing ("abtar" and "burnous"), or perhaps distinguishing the nomad (Butr) from the farmer (Baranis). The Arabs drew most of their early recruits from the Butr. Later, legends arose of an obscure, ancient invasion of Northwest Africa by the Himyarite

The Himyarite Kingdom ( ar, مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, he, ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar ( ar, حِمْيَر, ''Ḥimyar'', / 𐩹𐩧𐩺𐩵𐩬) (fl. 110 BCE–520s CE), historically referred to as the Homerite ...

Arabs of Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, from which a prehistoric ancestry was evidently fabricated: Berber descent from two brothers, Burnus and Abtar, who were sons of Barr, the grandson of Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

[ (]Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

being the grandson of Noah through his son Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term "ham ...

). Both Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) and Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

(994–1064) as well as Berber genealogists

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

held that the Himyarite Arab ancestry was totally unacceptable. This legendary ancestry, however, played a role in the long Arabization process that. continued for centuries among the Berber peoples.[

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the ]Sanhaja

The Sanhaja ( ber, Aẓnag, pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen; ar, صنهاجة, ''Ṣanhaja'' or زناگة ''Znaga'') were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Ma ...

, and the Masmuda

The Masmuda ( ar, المصمودة, Berber: ⵉⵎⵙⵎⵓⴷⵏ) is a Berber tribal confederation of Morocco and one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and the Sanhaja. They were composed of several sub-tribes: Berghouat ...

. The Zanata early on allied more closely with the Arabs and consequently became more Arabized, although Znatiya Berber is still spoken in small islands across Algeria and in northern Morocco (the Rif

The Rif or Riff (, ), also called Rif Mountains, is a geographic region in northern Morocco. This mountainous and fertile area is bordered by Cape Spartel and Tangier to the west, by Berkane and the Moulouya River to the east, by the Mediterrane ...

and north Middle Atlas

The Middle Atlas (Amazigh: ⴰⵟⵍⴰⵙ ⴰⵏⴰⵎⵎⴰⵙ, ''Atlas Anammas'', Arabic: الأطلس المتوسط, ''al-Aṭlas al-Mutawassiṭ'') is a mountain range in Morocco. It is part of the Atlas mountain range, a mountainous region ...

). The Sanhaja are also widely dispersed throughout the Maghrib, among which are: the sedentary Kabyle on the coast west of modern Algiers, the nomadic Zanaga

Zanaga is a town and capital of Zanaga District in the Lékoumou Department of northeastern Republic of the Congo.

It lies near the Ogooue River, which flows north into Gabon.

Mining

The city is near Zanaga mine, a potential 3 billion tonn ...

of southern Morocco (the south Anti-Atlas) and the western Sahara to Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

, and the Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern Alg ...

(al-Tawarik), the well-known camel breeding nomads of the central Sahara. The descendants of the Masmuda are sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soci ...

Berbers of Morocco, in the High Atlas

High Atlas, also called the Grand Atlas ( ar, الأطلس الكبير, Al-Aṭlas al-Kabīr; french: Haut Atlas; shi, ⴰⴷⵔⴰⵔ ⵏ ⴷⵔⵏ ''Adrar n Dern''), is a mountain range in central Morocco, North Africa, the highest part of t ...

, and from Rabat inland to Azru and Khanifra, the most populous of the modern Berber regions.[Generally, Jamil M. Abun-Nasr, ''A History of the Maghrib'' (Cambridge Univ. 1971) pp. 8–9.]

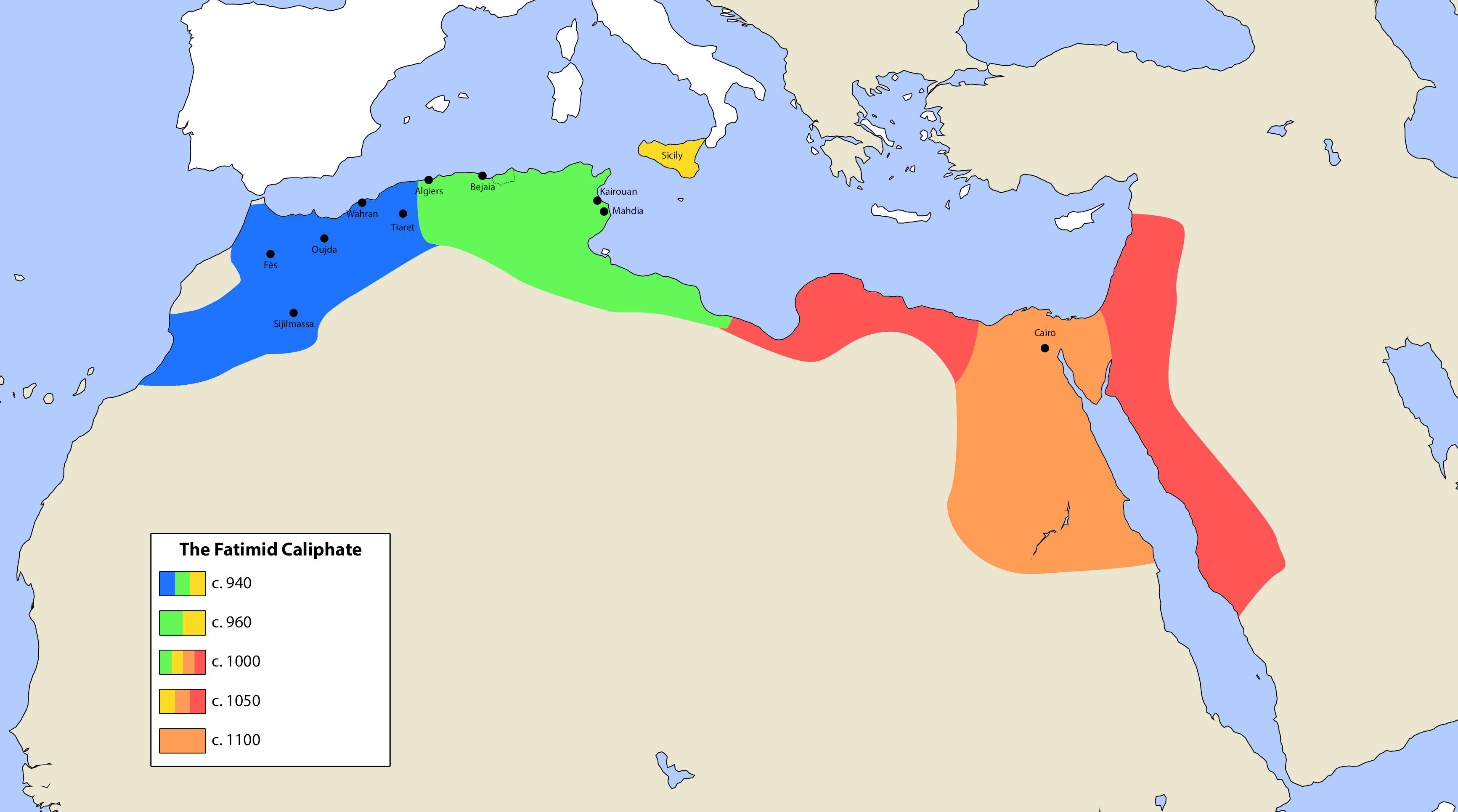

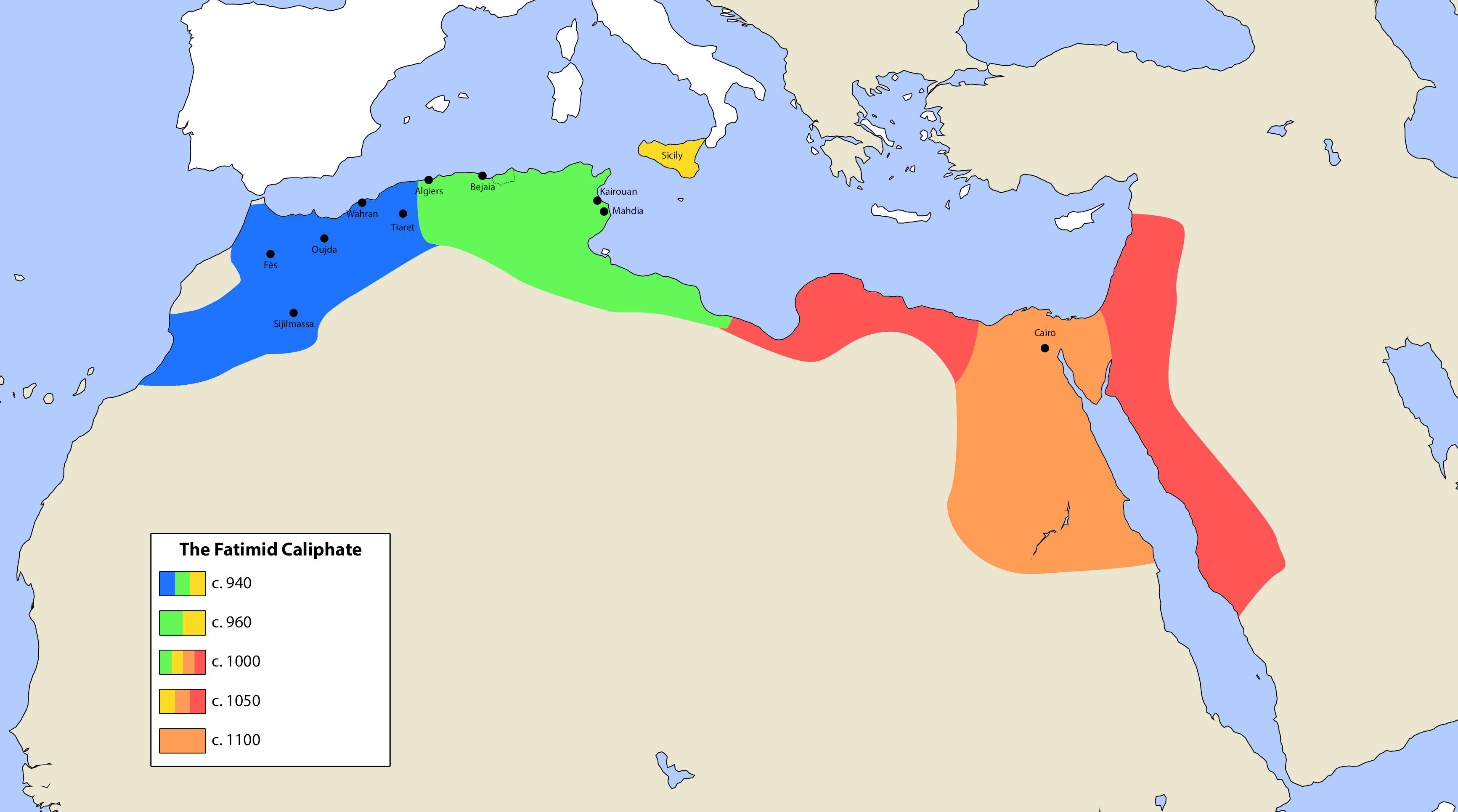

Medieval events in Ifriqiya and al-Maghrib often have tribal associations. Linked to the Kabyle ''Sanhaja'' were the Kutama

The Kutama ( Berber: ''Ikutamen''; ar, كتامة) was a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form ''Koidamousii'' by the Greek geographer Ptolemy. ...

tribes, whose support helped to establish the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171, only until 1049 in Ifriqiya); their vassals and later successors in Ifriqiya the Zirids

The Zirid dynasty ( ar, الزيريون, translit=az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri ( ar, بنو زيري, translit=banū zīrī), or the Zirid state ( ar, الدولة الزيرية, translit=ad-dawla az-zīriyya) was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from ...

(973–1160) were also ''Sanhaja''. The Almoravids (1056–1147) first began far south of Morocco, among the Lamtuna ''Sanhaja''.[ From the ''Masmuda'' came ]Ibn Tumart

Abu Abd Allah Amghar Ibn Tumart (Berber: ''Amghar ibn Tumert'', ar, أبو عبد الله امغار ابن تومرت, ca. 1080–1130 or 1128) was a Muslim Berber religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern Mor ...

and the Almohad movement (1130–1269), later supported by the ''Sanhaja''. Accordingly, it was from among the ''Masmuda'' that the Hafsid dynasty (1227–1574) of Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

originated.

Migrating peoples

The historical era opens with the advent of traders coming by sea from the eastern Mediterranean. Eventually they were followed by a stream of colonists, landing and settling along the coasts of Africa and Iberia, and on the islands of the western seas.

Technological innovations and economic development in the eastern Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, and along the Nile, increased the demand for various metals not found locally in sufficient quantity. Phoenician traders recognized the relative abundance and low cost of the needed metals among the goods offered for trade by local merchants in Hispania, which spurred trade. In the Phoenician city-state of Tyre, much of this Mediterranean commerce, as well as the corresponding trading settlements located at coastal stops along the way to the west, were directed by the kings, e.g., Hiram of Tyre (969–936).

By three thousand years ago the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and Hellas had enjoyed remarkable prosperity, resulting in population growth in excess of their economic base. On the other hand, political instability from time to time caused disruption of normal business and resulted in short-term economic distress. City-states started organizing their youth to migrate in groups to locations where the land was less densely settled. Importantly, the number of colonists coming from Greece was much larger than those coming from Phoenicia.

To these migrants, lands in the western Mediterranean presented an opportunity and could be reached relatively easily by ship, without marching through foreign territory. Colonists sailed westward following in the wake of their commercial traders. The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

arrived later, coming to (what is now) southern France, southern Italy including Sicily, and eastern Libya. Earlier the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns had settled in (what is now) Sardinia, Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Sicily, and Tunisia. In Tunisia the city of Carthage was founded, which would come to rule all the other Phoenician settlements.

Tunisia in its history has seen the arrival of many peoples. By three thousand years ago the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and Hellas had prospered, resulting in an excess of population for their economic base. Consequently, city-states started organizing their youth to migrate in groups to where land was less densely settled. To these migrants the western Mediterranean presented an opportunity and could be reached relatively easily by ship, without marching through foreign territory. Such colonists sailed westward across the seas, following the lead of their commercial traders. The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

arrived later, coming to (what is now) southern France, southern Italy including Sicily, and Libya. Earlier the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns had settled in (what is now) Sardinia, Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Sicily, and of course, Tunisia.

Throughout Tunisia's history many peoples have arrived among the Berbers to settle: most recently the French along with many Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

, before them came the Ottoman Turks with their multi-ethnic rule, yet earlier the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

who brought their language and the religion of Islam, and its calendar; before them arrived the Byzantines, and the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area betw ...

. Over two thousand years ago came the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, whose Empire long governed the region. The Phoenicians founded Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

close to three thousand years ago. Also came migrations from the Sahel region of Africa. Perhaps eight millennia ago, already there were peoples established among whom the proto-Berbers (coming from the east) mingled, and from whom the Berbers would spring, during an era of their ethno-genesis.[

]

Carthage

Foundation

The city of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

(site of its ruins near present-day Tunis) was founded by Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns coming from the eastern Mediterranean coast. Its name, pronounced ''Qart Hadesht'' in the Punic language

The Punic language, also called Phoenicio-Punic or Carthaginian, is an extinct variety of the Phoenician language, a Canaanite language of the Northwest Semitic branch of the Semitic languages. An offshoot of the Phoenician language of coastal W ...

that meant "new city" (It's cognate with Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, "Qarya Ħadītha", lit: "Modern Village/City). The Punic idiom is a Canaanite language

The Canaanite languages, or Canaanite dialects, are one of the three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Ugaritic, all originating in the Levant and Mesopotamia. They are attested in Canaanite inscriptions ...

, in the group of Northwest Semitic languages.

Timaeus of Taormina, a third century BC Greek historian from Sicily, gives the date of the founding of Carthage as thirty-eight years before the first Olympiad

An olympiad ( el, Ὀλυμπιάς, ''Olympiás'') is a period of four years, particularly those associated with the ancient and modern Olympic Games.

Although the ancient Olympics were established during Greece's Archaic Era, it was not unti ...

(776 BC), which in today's calendar would be the year 814 BC. Timaeus in Sicily was proximous to Cathaginians and their version of the city's foundation; his date is generally accepted as approximate. Ancient authors, such as Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (; 86 – ), was a Roman historian and politician from an Italian plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became during the 50s BC a partisan ...

and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, give founding dates several hundred years earlier for other Phoenician cities in the western Mediterranean, such as Utica and Gades, but recent archeology has been unable to verify these earlier dates.

It was Tyre, a major maritime city-state of Phoenicia, which first settled Carthage, probably in order to enjoy a permanent station there for its ongoing trade. Legends alive in the African city for centuries assigned its foundation to a queen of Tyre, Elissa, also called Dido

Dido ( ; , ), also known as Elissa ( , ), was the legendary founder and first queen of the Phoenician city-state of Carthage (located in modern Tunisia), in 814 BC.

In most accounts, she was the queen of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre (t ...

. The Roman historian Pompeius Trogus

Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus also anglicized as was a Gallo-Roman historian from the Celtic Vocontii tribe in Narbonese Gaul who lived during the reign of the emperor Augustus. He was nearly contemporary with Livy.

Life

Pompeius Trogus's grandfat ...

, a near contemporary of Virgil, describes a sinister web of court intrigue which caused Queen Elissa (Dido) to flee the city of Tyre westward with a fleet of ships. The Roman poet Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

(70–19 BC) portrays Dido as the tragic, admirable heroine of his epic the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of th ...

'', which contains many inventions loosely based on legendary history, and includes the story about how the Phoenician queen acquired the Byrsa

Byrsa was a walled citadel above the Phoenician harbour in ancient Carthage, Tunisia, as well as the name of the hill it rested on.

Legend

In Virgil's account of Dido's founding of Carthage, when Dido and her party were encamped at Byrsa, the l ...

.

Sovereignty

By the middle of the sixth century BC, Carthage had grown into a fully independent thalassocracy

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy sometimes also maritime empire, is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples ...

. Under Mago (r., c.550–530) and later his Magonid

The Magonids were a political dynasty of Ancient Carthage from 550 BCE to 340 BCE. The dynasty was first established under Mago I, under whom Carthage became pre-eminent among the Phoenician colonies in the western Mediterranean. Under the Magon ...

family, Carthage became preeminent among the Phoenician colonies in the western Mediterranean, which included nearby Utica.

Trading partnerships were established among the Numidian Berbers to the west along the African coast as well as to the east in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

; other stations were located in southern Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

and western Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Ibiza in the Balearics

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

, Lixus Lixus may refer to:

* ''lixus'', the Latin word for "boiled"

* Lixus (ancient city) in Morocco

* ''Lixus (beetle)'', a genus of true weevils

* Lixus, one of the sons of Aegyptus and Caliadne

Caliadne (; Ancient Greek: Καλιάδνης ) or Cali ...

south of the straits, and Gades north of the straits, with additional trading stations in the south and east of Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. Also, Carthage enjoyed an able ally in the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

, who then ruled a powerful state to the north of the infant city of Rome.

A merchant sailor of Carthage, Himilco, explored in the Atlantic to the north of the straits, along the coast of the Lusitanians

The Lusitanians ( la, Lusitani) were an Indo-European speaking people living in the west of the Iberian Peninsula prior to its conquest by the Roman Republic and the subsequent incorporation of the territory into the Roman province of Lusitania. ...

and perhaps as far as Oestrymnis (modern Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

), circa 500 BC. Carthage would soon supplant the Iberian city of Tartessus in carrying the tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

trade from Oestrymnis. Another, Hanno the Navigator explored the Atlantic to the south, along the African coast well past the River Gambia. The traders of Carthage were known to be secretive about business and particularly about trade routes; it was their practice to keep the straits to the Atlantic closed to the Greeks.

In the 530s there had been a three sided naval struggle between the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and the Etrusco-Punic allies; the Greeks lost Corsica to the Etruscans and Sardinia to Carthage. Then the Etruscans attacked Greek colonies in the Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

south of Rome, but unsuccessfully. As an eventual result, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

threw off their Etruscan kings of the Tarquin dynasty. The Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and Carthage in 509 entered into a treaty which set out to define their commercial zones.

Greek rivalry

The energetic presence of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

traders and their emporia in the Mediterranean region led to disputes over commercial spheres of influence, especially in Sicily. This Greek threat, plus the foreign conquest of Phoenicia in the Levant, had caused many Phoenician colonies to come under the leadership of Carthage. In 480 BC (concurrent with Persia's invasion of Greece), Mago's grandson Hamilcar __NOTOC__

Hamilcar ( xpu, 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤊 , ,. or , , "Melqart is Gracious"; grc-gre, Ἁμίλκας, ''Hamílkas'';) was a common Carthaginian masculine given name. The name was particularly common among the ruling families of ancient Carthage. ...

landed a large army in Sicily in order to confront Syracuse (a colony of Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

) on the island's eastern coast, but the Greeks prevailed at the Battle of Himera. A long struggle ensued with intermittent warfare between Syracuse led by e.g., the tyrant Dionysius I (r.405–367), and Carthage led by e.g., Hanno I the Great Hanno I the Great ( xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤀, ) was a Carthaginian politician and military leader of the 4th century BC.

The Roman historian Justin calls him ''princeps Carthaginiensium'', prince of the Carthaginians. The title almost certain ...

. Later, near Syracuse Punic armies defeated the Greek leader Agathocles Agathocles ( Greek: ) is a Greek name, the most famous of which is Agathocles of Syracuse, the tyrant of Syracuse. The name is derived from , ''agathos'', i.e. "good" and , ''kleos'', i.e. "glory".

Other personalities named Agathocles:

*Agathocles ...

(r.317–289) in battle, who then attempted a bold strategic departure by leaving Sicily and landing his forces at Cape Bon near Carthage, frightening the city. Yet Carthage again defeated Agathocles (310–307). Greece, preoccupied with its conquest of the Persian Empire in the east, eventually became supplanted in the western Mediterranean by Rome, the new rival of Carthage.

All this while Carthage enlarged its commercial sphere, venturing south to develop the Saharan trade, augmenting its markets along the African coast, in southern Iberia, and among the Mediterranean islands, and exploring in the far Atlantic. Carthage also established its authority directly among the Numidian Berber peoples in the lands immediately surrounding the city, which grew ever more prosperous.

Religion of Carthage

The Phoenicians of Tyre brought their lifestyle and inherited customs with them to Northwest Africa. Their religious practices and beliefs were generally similar to those of their neighbors in Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

, which in turn shared characteristics common throughout the ancient Semitic world. Several aspects of Canaanite religion have been widely criticized, particularly temple prostitution and child sacrifice. Canaanite religious sense and mythology do not appear as elaborated or developed as those of Mesopotamia. In Canaan the supreme god was called ''El'', which means "god" in common Semitic. The important storm god was called ''Baal'', which means "master". Other gods were called after royalty, e.g., ''Melqart'' means "king of the city".

The gods of the Semitic pantheon that were worshipped would depend on the identity of the particular city-state or tribe. After being transplanted to Africa far from its regional origins, and after co-existing with the surrounding Berber tribes, the original Phoenician pantheon and ways of worship evolved distinctly over time at the city-state of Carthage.

Constitution of Carthage

The government of Carthage was undoubtedly patterned after the Phoenician, especially the mother city of Tyre, but Phoenician cities had kings and Carthage apparently did not. An important office was called in Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

the ''Suffets'' (a Semitic word agnate with the Old Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew (, or , ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an wikt:archaic, archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanite branch of Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the ...

''Shophet'' usually translated as Judges as in the Book of Judges

The Book of Judges (, ') is the seventh book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. In the narrative of the Hebrew Bible, it covers the time between the conquest described in the Book of Joshua and the establishment of a kingdom ...

). Yet the Suffet at Carthage was more the executive leader, but as well served in a judicial role. Birth and wealth were the initial qualifications. It appears that the Suffet was elected by the citizens, and held office for a one-year term; probably there were two of them at a time; hence quite comparable to the Roman Consulship. A crucial difference was that the Suffet had no military power. Carthaginian generals marshalled mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

armies and were separately elected. From about 550 to 450 the Magonid family monopolized the top military position; later the Barcid family acted similarly. Eventually it came to be that, after a war, the commanding general had to testify justifying his actions before a court of 104 judges.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

(384–322, Greek) discusses Carthage in his ''Politica'' describing the city as a "mixed constitution", a political arrangement with cohabiting elements of monarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

, aristocracy, and democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

. Later Polybus of Megalopolis (c.204–122, Greek) in his ''Histories'' would describe the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

as a mixed constitution in which the Consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

were the monarchy, the Senate the aristocracy, and the Assemblies the democracy.

Evidently Carthage also had an institution of elders who advised the Suffets, similar to the Roman Senate. We do not have a name for this body. At times members would travel with an army general on campaign. Members also formed permanent committees. The institution had several hundred members from the wealthiest class who held office for life. Vacancies were probably filled by co-option. From among its members were selected the 104 Judges mentioned above. Later the 104 would come to judge not only army generals but other office holders as well. Aristotle regarded the 104 as most important; he compared it to the ephorate of Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

with regard to control over security. In Hannibal's time, such a Judge held office for life. At some stage there also came to be independent self-perpetuating boards of five who filled vacancies and supervised (non-military) government administration.

Popular assemblies also existed at Carthage. When deadlocked the Suffets and the quasi-senatorial institution might request the assembly to vote, or in very crucial matters in order to achieve political coherence. The assembly members had no ''legal'' wealth or birth qualification. How its members were selected is unknown, e.g., whether by festival group or urban ward or another method.

The Greeks were favorably impressed by the constitution of Carthage; Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

had a study of it made which unfortunately is lost. In the brief approving review of it found in his ''Politica'' Aristotle saw one fault: that focus on pursuit of wealth led to oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

. So it was in Carthage. The people were politically passive; popular rights came late. Being a commercial republic fielding a mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

army, the people were not conscripted for military service, an experience which can foster the feel for popular political action. On the other hand, Carthage was very stable; there were few openings for tyrants. "The superiority of their constitution is proved by the fact that the common people remain loyal," noted Aristotle. Only after defeat by Rome devastated Carthage's imperial ambitions did the people express interest in reform.

In 196, following the Second Punic War, Hannibal, still greatly admired as a Barcid military leader, was elected Suffet. When his reforms were blocked by a financial official about to become a Judge for life, Hannibal rallied the populace against the 104 Judges. He proposed a one-year term for the 104, as part of a major civic overhaul. His political opponents cravenly went to Rome and charged Hannibal with conspiracy, with plotting war against Rome in league with Antiochus the Hellenic ruler of Syria. Although Scipio Africanus resisted such maneuver, eventually Roman intervention forced Hannibal to leave Carthage. Thus corrupt officials of Carthage efficiently blocked Hannibal's efforts at reform.

The above description of the constitution basically follows Warmington. Largely it is taken from descriptions by Greek foreigners who likely would see in Carthage reflections of their own institutions. How strong was the Hellenizing influence within Carthage? The basic difficulty is the lack of adequate writings due to the secretive nature of the Punic state as well as to the utter destruction of the capital city and its records. Another view of the constitution of Carthage is given by Charles-Picard as follows.

Mago (6th century) was ''King'' of Carthage, Punic ''MLK'' or ''malik'' (Greek ''basileus''), not merely a ''SFT'' or ''Suffet'', which then was only a minor official. Mago as ''MLK'' was head of state and war leader; being ''MLK'' was also a religious office. His family was considered to possess a sacred quality. Mago's office was somewhat similar to that of Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

, but although kept in a family it was not hereditary, it was limited by legal consent; however, the council of elders and the popular assembly are late institutions. Carthage was founded by the ''King'' of Tyre who had a royal monopoly on this trading venture. Accordingly, royal authority was the traditional source of power the ''MLK'' of Carthage possessed. Later, as other Phoenician ship companies entered the trading region, and so associated with the city-state, the ''MLK'' of Carthage had to keep order among a rich variety of powerful merchants in their negotiations over risky commerce across the seas. The office of ''MLK'' began to be transformed, yet it was not until the aristocrats of Carthage became landowners that a council of elders was institutionalized.

Punic Wars with Rome

The emergence of the Roman Republic and its developing foreign interests led to sustained rivalry with Carthage for dominion of the western Mediterranean. As early as 509 BC Carthage and Rome had entered into treaty status, but eventually their opposing positions led to disagreement, alienation, and conflict.

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) started in Sicily. It developed into a naval war in which the Romans learned how to fight at sea and prevailed. Carthage lost Sardinia and its western portion of Sicily. Following their defeat, the Mercenary revolt threatened the social order of Carthage, which they survived under their opposing leaders Hanno II the Great

Hanno II the Great ( xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤀, ) was a wealthy Carthaginian aristocrat in the 3rd century BC.

Hanno's wealth was based on the land he owned in Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, and during the First Punic War he led the ...

, and Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas ( xpu, 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕𐤟𐤁𐤓𐤒, ''Ḥomilqart Baraq''; –228BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father- ...

, father of Hannibal.

The Second Punic War (218–201 BC) started over a dispute concerning Saguntum

Sagunto ( ca-valencia, Sagunt) is a municipality of Spain, located in the province of Valencia, Valencian Community. It belongs to the modern fertile ''comarca'' of Camp de Morvedre. It is located c. 30 km north of the city of Valencia, cl ...

(near modern Valencia) in Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hisp ...

, from whence Hannibal set out, leading his armies over the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

into Italy. At first Hannibal ("grace of Baal") won great military victories against Rome, at Trasimeno (217 BC) and at Cannae (216 BC), which came close to destroying Rome's ability to wage war. Yet the majority of Rome's Italian allies remained loyal; Rome drew on all her resources and managed to rebuild her military strength. For many years Hannibal remained on campaign in southern Italy. An attempt in 207 BC by his brother Hasdrubal to reinforce him failed. Meanwhile, Roman armies were contesting Carthage for the control of Hispania, in 211 BC the domain of armies under Hannibal's three brothers ( Hasdrubal and Mago), and Hasdrubal Gisco

Hasdrubal Gisco (died 202BC), a latinization of the name ʿAzrubaʿal son of Gersakkun ( xpu, 𐤏𐤆𐤓𐤁𐤏𐤋 𐤁𐤍 𐤂𐤓𐤎𐤊𐤍 ),. was a Carthaginian general who fought against Rome in Iberia (Hispania) and North Africa du ...

; by 206 BC the Roman general Cornelius Scipio (later Africanus) had defeated Punic power there. In 204 BC Rome landed armies at Utica near Carthage, which forced Hannibal's return. One Numidian king, Syphax, supported Carthage. Another, Masinissa

Masinissa ( nxm, , ''MSNSN''; ''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ult ...

, Rome. At the Battle of Zama

The Battle of Zama was fought in 202 BC near Zama, now in Tunisia, and marked the end of the Second Punic War. A Roman army led by Publius Cornelius Scipio, with crucial support from Numidian leader Masinissa, defeated the Carthaginian ...

in 202 BC the same Roman general Scipio Africanus defeated Hannibal, ending the long war. Carthage lost its trading cities in Hispania and elsewhere in the Western Mediterranean, and much of its influence over the Numidian Kingdoms in Northwest Africa. Carthage became reduced to its immediate surroundings. Also, it was required to pay a large indemnity to Rome. Carthage revived, causing great alarm in Rome.

The Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in modern northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 201 ...

(149–146 BC) began following the refusal by Carthage to alter the terms of its agreement with Rome. Roman armies again came to Africa and lay siege to the ancient and magnificent city of Carthage, which rejected negotiations. Eventually, the end came; Carthage was destroyed and its citizens enslaved.

Afterward The region (modern Tunisia) was annexed by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

as the Province of Africa. Carthage itself was eventually rebuilt by the Romans. Long after the fall of Rome, the city of Carthage would be again destroyed.

Roman Province of Africa

Republic and early Empire

The Province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

(basically what is now Tunisia and coastal regions to the east) became the scene of military campaigns directed by well known Romans during the last decades of the Republic. Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbric and Jugurthine wars, he held the office of consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his important refor ...

celebrated his ''triumph'' as a result of successfully finishing Rome's war against Jugurtha

Jugurtha or Jugurthen ( Libyco-Berber ''Yugurten'' or '' Yugarten'', c. 160 – 104 BC) was a king of Numidia. When the Numidian king Micipsa, who had adopted Jugurtha, died in 118 BC, Jugurtha and his two adoptive brothers, Hiempsal and A ...

, the Numidian king. A wealthy ''novus homo

''Novus homo'' or ''homo novus'' (Latin for 'new man'; ''novi homines'' or ''homines novi'') was the term in ancient Rome for a man who was the first in his family to serve in the Roman Senate or, more specifically, to be elected as consul. Whe ...

'' and populares, Marius was the first Roman general to enlist in his army '' proletari'' (landless citizens); he was chosen Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

an unprecedented seven times (107, 104–100, 86). The optimate

Optimates (; Latin for "best ones", ) and populares (; Latin for "supporters of the people", ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated academic dis ...

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla ha ...

, later Consul (88, 80), and Dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in tim ...

(82–79), had served as quaestor under the military command of Marius in Numidia. There in 106 Sulla persuaded Bocchus to hand over Jurgurtha, which ended the war.

In 47 BC Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

landed in Africa in pursuit of Pompey's remnant army, which was headquartered at Utica where they enjoyed the support of the Numidian King Juba I

Juba I of Numidia ( lat, IVBA, xpu, ywbʿy; –46BC) was a king of Numidia (reigned 60–46 BC). He was the son and successor to Hiempsal II.

Biography

In 81 BC Hiempsal had been driven from his throne; soon afterwards, Pompey was sent to Af ...

. Also present was Cato the Younger

Marcus Porcius Cato "Uticensis" ("of Utica"; ; 95 BC – April 46 BC), also known as Cato the Younger ( la, Cato Minor), was an influential conservative Roman senator during the late Republic. His conservative principles were focused on the ...

, a political leader of Caesar's republican opponents. Caesar's victory nearby at the Battle of Thapsus

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

almost put an end to at phase of the civil war. Cato committed suicide by his sword. Caesar then annexed Numidia (the eastern region of modern Algeria).

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

(ruled 31 BC to 14 AD) controlled the Roman state following the civil war that would mark the end of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

. He established a quasi-constitutional regime known as the ''Principate'', later to be called the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

.

Augustus circa 27 BC restored Juba II

Juba II or Juba of Mauretania (Latin: ''Gaius Iulius Iuba''; grc, Ἰóβας, Ἰóβα or ;Roller, Duane W. (2003) ''The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene'' "Routledge (UK)". pp. 1–3. . c. 48 BC – AD 23) was the son of Juba I and client ...

to the throne as King of Mauretania (to the east of the Province of Africa). Educated at Rome and obviously a client king, Juba also wrote books about the culture and history of Africa, and a best seller about Arabia, writings unfortunately lost. He married Cleopatra Selene, the daughter of Anthony and Cleopatra. After his reign, his kingdom and other lands of the Maghrib

The Maghrib Prayer ( ar, صلاة المغرب ', "sunset prayer") is one of the five mandatory salah (Islamic prayer). As an Islamic day starts at sunset, the Maghrib prayer is technically the first prayer of the day. If counted from midni ...

were annexed as the Roman Provinces of Mauritania Caesaria and Mauritania Tingitana (approximately the western coast of modern Algeria and northern Morocco).[

]

Renaissance of Carthage

Rebuilding of the city of Carthage began under Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

and, notwithstanding reported ill omens, Carthage flourished during the 1st and 2nd centuries. The capital of the Province of Africa, where a Roman ''praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

'' or ''proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ...

'' resided, was soon moved from nearby Utica back to Carthage. Its rich agriculture made the province wealthy; olives and grapes were important products, but by its large exports of wheat. it became famous. Marble, wood, and mules were also important exports. New towns were founded, especially in the Majarda valley near Carthage; many prior Punic and Berber settlements prospered.

Expeditions ventured south into the Sahara. Cornelius Balbus, Roman governor at Utica, in 19 BC occupied Gerama, desert capital of the Garamantes

The Garamantes ( grc, Γαράμαντες, translit=Garámantes; la, Garamantes) were an ancient civilisation based primarily in present-day Libya. They most likely descended from Iron Age Berber tribes from the Sahara, although the earliest kn ...

in the Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

. These Berber Garamantes had long-time, unpredictable, off-and-on contacts with the Mediterranean. Extensive trade across the Sahara directly with the lands to the south had not yet developed.[Richard W. Bulliet, ''The Camel and the Wheel'' (Harvard Univ. 1975) pp. 113, 138.][A. Bathily, "Relations between the different regions of Africa" pp. 348–357, 350, in ''General History of Africa, volume III, Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century'' (UNESCO 1992).]

People from all over the Empire began to migrate into Africa Province, e.g., veterans

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in a particular occupation or field. A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in a military.

A military veteran that h ...

in early retirement settled in Africa on farming plots promised for their military service. A sizable Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

speaking population at was multinational developed, which shared the region with those speaking the Punic and Berber languages. The local population began eventually to provide the Roman security forces. That the Romans "did not display any racial exclusiveness and were remarkably tolerant of Berber religious cults" facilitated local acceptance of their rule. Here the Romans evidently governed well enough that the Province of Africa became integrated into the economy and culture of the Empire, with Carthage as one of its major cities.

Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern- ...

(c.125–c.185) managed to thrive in the professional and literary communities of Latin-speaking Carthage. A full Berber (Numidian

Numidia (Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisi ...

and Gaetulian) of Madaura whose father was a provincial magistrate, he studied at Carthage, and later at Athens (philosophy) and at Rome (oratory), where he evidently served as a legal advocate. He also traveled to Asia Minor and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

. Returning to Carthage he married an older, wealthy widow; he then was prosecuted for using magic to gain her affections. His speech in defense makes up his ''Apology''; apparently he was acquitted. His celebrated work ''Metamorphosus, or the Golden Ass'' is an urbane, extravagant, inventive novel of the ancient world. at Carthage he wrote philosophy, rhetoric, and poetry; several statues were erected in his honor. St. Augustine discusses Apuleius in his ''The City of God

''On the City of God Against the Pagans'' ( la, De civitate Dei contra paganos), often called ''The City of God'', is a book of Christian philosophy written in Latin by Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD. The book was in response ...

''. Apuleius used a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

style at registered as "New Speech" recognized by his literary contemporaries. It expressed the everyday language used by the educated, along with embedded archaisms, which transformed the more formal, classical grammar favored by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

(106–43), and pointed toward the development of modern Romance idioms. Apuleius was drawn to the mystery religions, particularly the cult of Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

.

Many native Berbers adopted to the Mediterranean-wide influences operating in the province, eventually intermarrying, or entering into the local aristocracy. Yet the majority did not. There remained a social hierarchy of the Romanized, the partly assimilated, and the unassimilated, many of whom were Berbers. These imperial distinctions overlay the preexisting stratification of economic classes, e.g., there continued the practice of slavery, and there remained a co-opted remnant of the wealthy Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

aristocracy. The stepped-up pace and economic demands of a cosmopolitan urban life could have a very negative impact on the welfare of the rural poor. Large estates (''latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious" and ''fundus'', "farm, estate") is a very extensive parcel of privately owned land. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, o ...

'') at produced crops for export, often were managed for absentee owners and used slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

; these occupied lands previously tilled by small local farmers. On another interface, tensions increased between pastoral nomads, who had their herds to graze, and sedentary farmers, with the best land being appropriated for planting, usually by the better-connected. These social divisions would manifest in various ways, e.g., the collateral revolt in 238, and the radical edge to the Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and the ...

schism.

Emperors from Africa

Septimus Severus (145–211, r.193–211) was born of mixed Punic Ancestry in Lepcis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was great ...

, Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

(now Libya), where he spent his youth. Although he was said to speak with a Northwest African accent, he and his family were long members of the Roman cosmopolitan elite. His eighteen-year reign was noted for frontier military campaigns. His wife Julia Domna

Julia Domna (; – 217 AD) was Roman empress from 193 to 211 as the wife of Emperor Septimius Severus. She was the first empress of the Severan dynasty. Domna was born in Emesa (present-day Homs) in Roman Syria to an Arab family of priests ...

of Emesa

ar, حمصي, Himsi

, population_urban =

, population_density_urban_km2 =

, population_density_urban_sq_mi =

, population_blank1_title = Ethnicities

, population_blank1 =

, population_blank2_t ...

, Syria, was from a prominent family of priestly rulers there; as empress in Rome she cultivated a salon which may have included Ulpian

Ulpian (; la, Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus; c. 170223? 228?) was a Roman jurist born in Tyre. He was considered one of the great legal authorities of his time and was one of the five jurists upon whom decisions were to be based according to ...

of Tyre, the jurist of Roman Law. After Severus (whose reign was well regarded), his son Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor S ...