The history of the

island of Taiwan dates back tens of thousands of years to the earliest known evidence of human habitation. The sudden appearance of a culture based on

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

around 3000 BC is believed to reflect the arrival of the ancestors of today's

Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Taiwanese indigenous peoples (formerly Taiwanese aborigines), also known as Formosan people, Austronesian Taiwanese, Yuanzhumin or Gaoshan people, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 5 ...

. From the late 13th to early 17th centuries,

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctiv ...

gradually came into contact with Taiwan and started settling there. Named

Formosa by

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

explorers, the south of the island was

colonized by the Dutch in the 17th century whilst the Spanish built a

settlement in the north which lasted until 1642. These European settlements were followed by an influx of

Hoklo and

Hakka immigrants from the

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

and

Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

areas of

mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

, across the

Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself a ...

.

In 1662,

Koxinga

Zheng Chenggong, Prince of Yanping (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), better known internationally as Koxinga (), was a Ming loyalist general who resisted the Qing conquest of China in the 17th century, fighting them on China's southeastern ...

, a loyalist of the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

who had lost control of mainland China in 1644, defeated the Dutch and established a

base of operations on the island. His descendants were defeated by the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

in 1683 and their territory in Taiwan was

annexed by the Qing dynasty. The Qing dynasty gradually extended its control over the western plains and northeast of Taiwan in the following two centuries. Under Qing rule, Taiwan's population became majority

Han due to migration from mainland China. The Qing

ceded Taiwan and

Penghu to the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

after losing the

First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. Taiwan experienced industrial growth and became a productive rice and sugar exporting Japanese colony. During the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

it served as a base for launching invasions of China, and later

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainlan ...

and

the Pacific during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

Japanese imperial education was implemented in Taiwan and many Taiwanese fought for Japan in the last years of the war.

In 1945, following the end hostilities in World War II, the

nationalist government of the

Republic of China (ROC), led by the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

(KMT), took control of Taiwan. The legality and nature of its control of Taiwan, including transfer of sovereignty is debated, with the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

saying there was no transfer of sovereignty. In 1949, after losing control of

mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

in the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

, the ROC government under the KMT

withdrew to Taiwan where

Chiang Kai-shek declared

martial law. The KMT ruled Taiwan (along with the islands of

Kinmen

Kinmen, alternatively known as Quemoy, is a group of islands governed as a county by the Republic of China (Taiwan), off the southeastern coast of mainland China. It lies roughly east of the city of Xiamen in Fujian, from which it is separat ...

,

Wuqiu and the

Matsu on the opposite side of the

Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself a ...

) as a

single-party state for forty years until democratic reforms in the 1980s. The first-ever

direct presidential election was held in 1996. During the post-war period, Taiwan experienced rapid industrialization and economic growth known as the "

Taiwan Miracle

The Taiwan Miracle () or Taiwan Economic Miracle refers to the rapid industrialization and economic growth of Taiwan during the latter half of the twentieth century.

As it developed alongside Singapore, South Korea and Hong Kong, Taiwan became ...

", and was known as one of the "

Four Asian Tigers

The Four Asian Tigers (also known as the Four Asian Dragons or Four Little Dragons in Chinese and Korean) are the developed East Asian economies of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Between the early 1960s and 1990s, they underwent ...

".

Prehistory

In the

Late Pleistocene, sea levels were about 140 m lower than in the present day, exposing the floor of the shallow

Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself a ...

as a land bridge that was crossed by mainland fauna. A concentration of

vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with c ...

fossils has been found in the channel between the Penghu Islands and Taiwan, including a partial jawbone designated

Penghu 1, apparently belonging to a previously unknown species of genus ''

Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus '' Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely relat ...

''.

These fossils are dated 450,000 to 190,000 years ago. The oldest evidence of modern human presence on Taiwan consists of three cranial fragments and a molar tooth found at Chouqu and Gangzilin, in

Zuojhen District

Zuojhen District, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency () is a rural district of about 4,410 residents in Tainan, Taiwan.

History

After the handover of Taiwan from Japan to the Republic of China in 1945, Zuojhen was organi ...

, Tainan. These are estimated to be between 20,000 and 30,000 years old. The oldest artefacts are chipped-pebble tools of the

Paleolithic Changbin culture found in four caves in

Changbin, Taitung, dated 15,000 to 5,000 years ago, and similar to contemporary sites in Fujian. The same culture is found at sites at

Eluanbi

Cape Eluanbi or Oluanpi, also known by other names, is the southernmost point on the island of Taiwan. It is located in within the Hengchun Township in Pingtung County.

Names

''Éluánbí'' is the pinyin romanization of the Mandarin pr ...

on the southern tip of Taiwan, persisting until 5,000 years ago. Analysis of

spores and

pollen grains in

sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sa ...

of

Sun Moon Lake

Sun Moon Lake (; Thao: ''Zintun'') is a lake in Yuchi Township, Nantou County, Taiwan. It is the largest body of water in Taiwan. The area around the lake is home to the Thao tribe, one of aboriginal tribes of Taiwan. Sun Moon Lake surrou ...

suggests that traces of

slash-and-burn

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a farming method that involves the cutting and burning of plants in a forest or woodland to create a field called a swidden. The method begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The downed veget ...

agriculture started in the area since 11,000 years ago, and ended 4,200 years ago, when abundant remains of

rice cultivation

The history of rice cultivation is an interdisciplinary subject that studies archaeological and documentary evidence to explain how rice was first domesticated and cultivated by humans, the spread of cultivation to different regions of the planet, ...

were found in such period.

At the beginning of the

Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

10,000 years ago, sea levels rose, forming the Taiwan Strait and cutting off the island from the Asian mainland.

In December 2011, the ~8,000 year old Liangdao Man skeleton was found on

Liang Island. In 2014, the mitochondrial DNA of the skeleton was found to belong to

Haplogroup E, with two of the four mutations characteristic of the E1 subgroup.

The only Paleolithic burial that has been found on Taiwan was in Xiaoma cave in

Chenggong in the southeast of the island, dating from about 4000 BC, of a male similar in type to

Negrito

The term Negrito () refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations often described as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples (including the Great Andamanese, the O ...

s found in the Philippines.

There are also references in Chinese texts and Taiwanese aboriginal oral traditions to pygmies on the island at some time in the past.

Around 3,000 BC, the Neolithic

Dapenkeng culture abruptly appeared and quickly spread around the coast of the island. Their sites are characterised by corded-ware pottery, polished stone adzes and slate points. The inhabitants cultivated rice and millet, but were also heavily reliant on marine shells and fish. Most scholars believe this culture is not derived from the Changbin culture, but was brought across the Strait by the ancestors of today's

Taiwanese aborigines

Taiwanese may refer to:

* Taiwanese language, another name for Taiwanese Hokkien

* Something from or related to Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China ...

, speaking early

Austronesian languages. Some of these people later migrated from Taiwan to the islands of Southeast Asia and thence throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Malayo-Polynesian languages

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages, with approximately 385.5 million speakers. The Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by the Austronesian peoples outside of Taiwan, in the island nations of Southeas ...

are now spoken across a huge area from

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

to

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

,

Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its ne ...

and

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, but form only one branch of the Austronesian family, the rest of whose branches are found only on Taiwan.

Trade links with the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

continued from the early 2nd millennium BC, including the use of

jade from eastern Taiwan in the

Philippine jade culture.

The Dapenkeng culture was succeeded by a variety of cultures throughout the island, including the

Tahu and

Yingpu cultures.

Iron appeared at the beginning of the current era in such cultures as the

Niaosung Culture The Niaosung Culture () was an archaeological culture in southern Taiwan. It distributed around the region of Tainan and Kaohsiung. The culture existed in the Iron Age of Taiwan island. Some evidences suggested that Niaosung Culture was directly rel ...

.

The earliest metal artifacts were trade goods, but by around 400 AD

wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

was being produced locally using

bloomeries, a technology possibly introduced from the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

.

Chinese contact and settlement

Early Chinese histories refer to visits to eastern islands that some historians identify with Taiwan. Troops of the

Three Kingdoms

The Three Kingdoms () from 220 to 280 AD was the tripartite division of China among the dynastic states of Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu. The Three Kingdoms period was preceded by the Eastern Han dynasty and was followed by the West ...

state of

Eastern Wu are recorded visiting an island known as

Yizhou in the spring of 230. They brought back several thousand natives but 80 to 90 percent of the soldiers died to unknown diseases. Some scholars have identified this island as Taiwan while others do not. The ''

Book of Sui

The ''Book of Sui'' (''Suí Shū'') is the official history of the Sui dynasty. It ranks among the official Twenty-Four Histories of imperial China. It was written by Yan Shigu, Kong Yingda, and Zhangsun Wuji, with Wei Zheng as the lead author. ...

'' relates that

Emperor Yang of the

Sui dynasty sent three expeditions to a place called "

Liuqiu" early in the 7th century. They brought back captives, cloth, and armour. The Liuqiu described by the ''Book of Sui'' had pigs and chicken but no cows, sheep, donkeys, or horses. It produced little iron, had no writing system, taxation, or penal code, and was ruled by a king with four or five commanders. The natives used stone blades and practiced

slash-and-burn

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a farming method that involves the cutting and burning of plants in a forest or woodland to create a field called a swidden. The method begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The downed veget ...

agriculture to grow rice, millet, sorghum, and beans. Later the name Liuqiu (whose characters are read in Japanese as "

Ryukyu

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonagu ...

") referred to the island chain to the northeast of Taiwan, but some scholars believe it may have referred to Taiwan in the Sui period.

Okinawa Island was referred to by the Chinese as "Great Liuqiu" and Taiwan as "Lesser Liuqiu".

During the

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

(1271–1368),

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctiv ...

people started visiting Taiwan. The Yuan emperor

Kublai Khan sent officials to the

Ryukyu Kingdom

The Ryukyu Kingdom, Middle Chinese: , , Classical Chinese: (), Historical English names: ''Lew Chew'', ''Lewchew'', ''Luchu'', and ''Loochoo'', Historical French name: ''Liou-tchou'', Historical Dutch name: ''Lioe-kioe'' was a kingdom in the ...

in 1292 to demand its loyalty to the Yuan dynasty, but the officials ended up in Taiwan and mistook it for Ryukyu. After three soldiers were killed, the delegation immediately retreated to

Quanzhou in China. Another expedition was sent in 1297.

Wang Dayuan Wang Dayuan (, fl. 1311–1350), courtesy name Huanzhang (), was a Chinese traveller of the Yuan dynasty from Quanzhou in the 14th century. He is known for his two major ship voyages.

Wang Dayuan was born around 1311 at Hongzhou (present-day Nan ...

visited Taiwan in 1349 and noted that he did not find any Chinese there and the people were different from Penghu's population. He mentioned the presence of Chuhou pottery from present day

Lishui,

Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , Chinese postal romanization, also romanized as Chekiang) is an East China, eastern, coastal Provinces of China, province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable citie ...

, suggesting that Chinese merchants had already visited the island by the 1340s.

By the early 16th century, increasing numbers of Chinese fishermen, traders and pirates were visiting the southwestern part of the island. Some merchants from

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

were familiar enough with the indigenous peoples of Taiwan to speak

Formosan languages

The Formosan languages are a geographic grouping comprising the languages of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, all of which are Austronesian. They do not form a single subfamily of Austronesian but rather nine separate subfamilies. The Taiwa ...

. The people of Fujian sailed closer to Taiwan and the Ryukyus in the mid-16th century to trade with Japan while evading Ming authorities. Chinese who traded in Southeast Asia also began taking an East Sea Compass Course (''dongyang zhenlu'') that passed southwestern and southern Taiwan. Some of them traded with the Taiwanese aborigines. During this period, Taiwan was referred to as ''Xiaodong dao'' ("little eastern island") and ''Dahui guo'' ("the country of Dahui"), a corruption of Tayouan, a tribe that lived on an islet near modern

Tainan

Tainan (), officially Tainan City, is a special municipality in southern Taiwan facing the Taiwan Strait on its western coast. Tainan is the oldest city on the island and also commonly known as the "Capital City" for its over 200 years of his ...

from which the name "Taiwan" is derived. By the late 16th century, Chinese from Fujian were settling in southwestern Taiwan. The Chinese pirates

Lin Daoqian

Lin Daoqian (, Malay: Tok Kayan, th, ลิ้มโต๊ะเคี่ยม), also written as Lim Toh Khiam and Vintoquián, was a Chinese pirate of Teochew origin active in the 16th century. He led pirate attacks along the coast of Guangd ...

and

Lin Feng visited Taiwan in 1563 and 1574 respectively. Lin Daoqian was a pirate from

Chaozhou who fled to

Beigang

Beigang, Hokkō or Peikang is an Township (Taiwan), urban township in Yunlin County, Taiwan. It is primarily known for its Chaotian Temple, one of the most prominent temples of Mazu, Temples of Lin Moniang, Mazu on Taiwan. It has a population of ...

in southwestern Taiwan and left shortly after. Lin Feng moved his pirate forces to Wankan (in modern

Chiayi County

Chiayi County ( Mandarin pinyin: ''jiā yì xiàn''; Hokkien POJ: ''Ka-gī-koān'') is a county in southwestern Taiwan surrounding but not including Chiayi City. It is the sixth largest county in Taiwan.

Name

The former Chinese placename wa ...

) in Taiwan on 3 November 1574 and used it as a base to launch raids. They left for Penghu after being attacked by natives and the Ming navy dislodged them from their bases. He later returned to Wankan on 27 December 1575 but left for Southeast Asia after losing a naval encounter with Ming forces on 15 January 1576. The pirate

Yan Siqi also used Taiwan as a base. In 1593,

Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

officials started issuing ten licenses each year for Chinese junks to trade in northern Taiwan. Chinese records show that after 1593, each year five licenses were granted for trade in

Keelung and five licenses for

Tamsui

Tamsui District (Hokkien POJ: ''Tām-chúi''; Hokkien Tâi-lô: ''Tām-tsuí''; Mandarin Pinyin: ''Dànshuǐ'') is a seaside district in New Taipei, Taiwan. It is named after the Tamsui River; the name means "fresh water". The town is popul ...

. However these licenses merely acknowledged already existing illegal trade at these locations.

Initially Chinese merchants arrived in northern Taiwan and sold iron and textiles to the aboriginal peoples in return for coal, sulfur, gold, and venison. Later the southwestern part of Taiwan surpassed northern Taiwan as the destination for Chinese traders. The southwest had mullet fish, which drew more than a hundred fishing junks from Fujian each year during winter. The fishing season lasted six to eight weeks. Some of them camped on Taiwan's shores and many began trading with the indigenous people for deer products. The southwestern Taiwanese trade was of minor importance until after 1567 when it was used as a way to circumvent the ban on Sino-Japanese trade. The Chinese bought deerskins from the aborigines and sold them to the Japanese for a large profit.

When a Portuguese ship sailed past southwestern Taiwan in 1596, several of its crew members who had been shipwrecked there in 1582 noticed that the land had become cultivated and now had people working it, presumably by Chinese settlers from Fujian. When the Dutch arrived in 1623, they found about 1,500 Chinese visitors and residents. Most of them were engaged in seasonal fishing, hunting, and trading. The population fluctuated throughout the year peaking during winter. A small minority brought Chinese plants with them and grew crops such as apples, oranges, bananas, watermelons. Some estimates of the Chinese population put it at 2,000. There were two Chinese villages. The larger one was located on an island that formed the Bay of Tayouan. It was inhabited year-round. The smaller village was located on the mainland and would eventually become the city of Tainan. In the early 17th century, a Chinese man described it as being inhabited by pirates and fishermen. One Dutch visitor noted that an aboriginal village near the Sino-Japanese trade center had a large number of Chinese and there was "scarcely a house in this village . . . that does not have one or two or three, or even five or six Chinese living there." The villagers' speech contained many Chinese words and sounded like "a mixed and broken language."

Chinese descriptions of Taiwan

Wang Dayuan

In 1349,

Wang Dayuan Wang Dayuan (, fl. 1311–1350), courtesy name Huanzhang (), was a Chinese traveller of the Yuan dynasty from Quanzhou in the 14th century. He is known for his two major ship voyages.

Wang Dayuan was born around 1311 at Hongzhou (present-day Nan ...

provided the first written account of a visit to Taiwan. He found no Chinese settlers there but many on

Penghu.

Wang called different regions of Taiwan ''Liuqiu'' and ''Pisheye''. According to Wang, Liuqiu was a vast land of huge trees and mountains named Cuilu, Zhongman, Futou, and Dazhi. A mountain could be seen from Penghu. He climbed the mountain and could see the coasts. Wang described a rich land with fertile fields that was hotter than Penghu. Its people had different customs from Penghu. They did not have boats and oars but only rafts. The men and women bound their hair and wore colored garments. They obtained salt from boiled sea water and liquor from fermented sugarcane juice. There were barbarian lords and chiefs that were respected by the people and they had a bone-and-flesh relationship between father and son. They practiced cannibalism against their enemies. The land's products included gold, beans, millet, sulphur, beeswax, deer hide, leopards, and moose. They accepted pearls, agates, gold, beads, dishware, and pottery as items of trade.

According to Wang, Pisheye was located to the east. It had extensive mountains and plains but the people did not engage in much agriculture or produce any products. The weather was hotter than Liuqiu. Its people wore their hair in tufts, tattooed their bodies with black juice, and wrapped red silk and yellow cloth around their heads. Pisheye had no chief. Its people hid in wild mountains and solitary valleys. They practiced raiding and plundering by boat. Kidnapping and slave trading were common. The historian Efren B. Isorena, through analysis of historical accounts and wind currents in the Pacific side of East and Southeast Asia, concluded that the Pisheye of Taiwan and the Bisaya of the

Visayas islands in the Philippines, were closely related people as Visayans were recorded to have travelled to Taiwan from the Philippines via the northward windcurrents before they raided China and returned south after the southwards monsoon during summer.

Chen Di

In the winter of 1602–1603,

Chen Di visited Taiwan on an expedition against the

Wokou

''Wokou'' (; Japanese: ''Wakō''; Korean: 왜구 ''Waegu''), which literally translates to "Japanese pirates" or "dwarf pirates", were pirates who raided the coastlines of China and Korea from the 13th century to the 16th century. pirates. General Shen of Wuyu defeated the wokou and met with the chieftain Damila, who presented gifts of deer and liquor as thanks for getting rid of the pirates. Chen witnessed these events and wrote an account of Taiwan known as ''Dongfanji'' (An Account of the Eastern Barbarians).

According to Chen, the Eastern Barbarians lived on an island beyond Penghu. They lived in Wanggang, Jialaowan, Dayuan (variation of Taiwan), Yaogang, Dagouyu, Xiao Danshui, Shuangqikou, Jialilin, Shabali, and Dabangkeng. Their land extended several thousand ''li'' covering villages where people lived separately in groups of five hundred to a thousand people. They had no chief but the one with the most children, who was considered a hero and obeyed by the populace. The people liked to fight and run in their free time so that the soles of their feet were very thick, able to tread on thorny brushes. They ran as fast as a horse. Chen figured they could cover several hundred ''li'' in a day. During quarrels between villages, they sent warriors to kill each other on an agreed upon date, but the conflicts ended without any enmity between them. They practiced headhunting. Thieves were killed at the village altar.

The land was warm to the point that people wore no clothes during winter. Women wore plait grass skirts that only covered their lower body. The men cut their hair while the women did not. The men pierced their ears while the women decorated their teeth. Chen considered the women to be sturdy and active, working constantly, while the men usually idled. They did not bow or kneel. They had no knowledge of a calendar or writing and understood a full moon cycle as a month with a year being ten months. They eventually forgot the count and lost track of their own age.

Their houses were made with thatch and bamboo, which grew tall and thick in abundance. Tribes had a common-house where all the unmarried boys lived. Matters of deliberation were discussed at the common-house. When a boy saw a girl he wished to marry, he sent her a pair of agate beads. If the girl accepted them, the boy went to her house at night and played an instrument called the ''kouqin''. Upon acknowledgement by the girl, the boy stayed the night. When a child was born, she went to the man's home to fetch him back as a son-in-law and he would live with her family supporting them for the rest of their lives. Girls were preferred because of this. Men could remarry upon their wives' death but not women. Corpses were dried and buried beneath their families' houses when they needed to be rebuilt.

They did not have irrigated fields and cleared areas by fire before planting their crop. Once the mountain flowers bloomed they plowed their fields and once the grain ripened they were plucked. Their grains included soya bean, lentil, sesame, pearl-barley, but no wheat. For vegetables they had onions, ginger, sweet potatoes, and taro. For fruits they had coconuts, persimmons, citron and sugarcane. Rice grains were longer and tastier than the grains Chen was accustomed to. They gathered herbs and mixed them with fermented rice to make liquor. During banquets they drank the liquor by pouring it into a bamboo tube. No food was served during these occasions. They danced and sang songs to music. For domesticated animals they had cats, dogs, pigs, and chicken, but not horses, donkeys, cattle, sheep, geese, or deer. There were wild tigers, bears, leopards, and deer. Deer inhabited the mountains and moved in herds of a hundred or a thousand. Men hunted deer using spears made of bamboo shafts and iron points. They also hunted tigers. Deer hunts only occurred in the winter when they came out in herds. They ate deer meat and pig meat but not chicken.

Although they lived on an island they did not have boats and feared the sea. They only fished in small streams. They had no contact with any of the non-Chinese peoples outside Taiwan. During the

Yongle period (1403-1424),

Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferr ...

carried an Imperial Edict to the Eastern Barbarians, but the indigenous people of Taiwan remained hidden and would not be coerced. Their families were given brass bells to hang around their necks to symbolize their status as dogs, but they kept the bells and handed them down as treasures. During the 1560s the wokou attacked the indigenous people of Taiwan with firearms, forcing them into the mountains. Afterwards they came into contact with China. Chinese from the harbors of Huimin, Chonglong, and Lieyu in

Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou (), alternately romanized as Changchow, is a prefecture-level city in Fujian Province, China. The prefecture around the city proper comprises the southeast corner of the province, facing the Taiwan Strait and surrounding the prefect ...

and Quanzhou learned their languages to trade with them. The Chinese traded things like agate beads, porcelain, cloth, salt, and brass in return for deer meat, skins, and horns. They obtained Chinese clothing that they only put on while dealing with the Chinese and took them off for storage afterwards. Chen saw their way of life, without hat or shoe, going about naked, to be easy and simple.

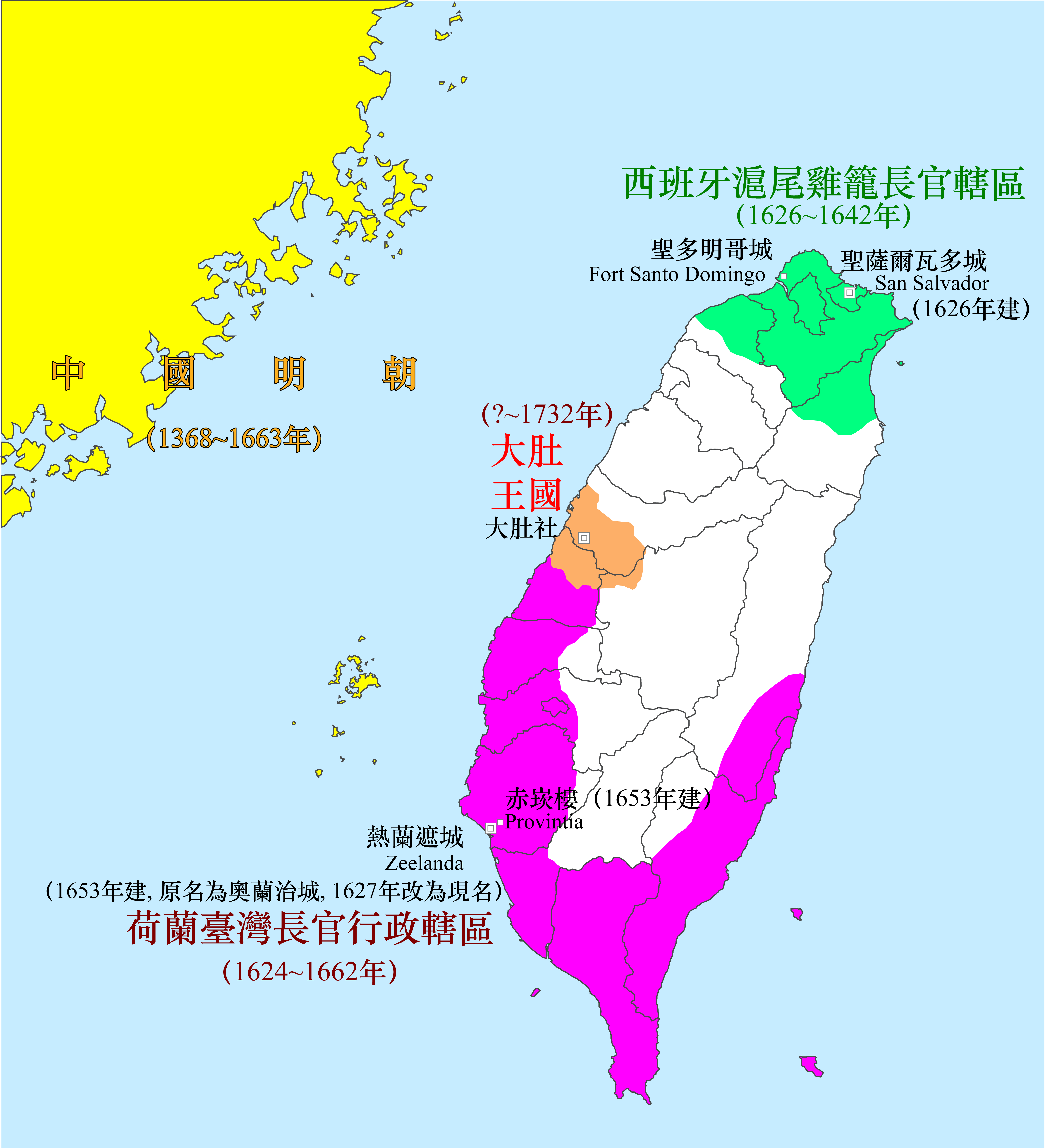

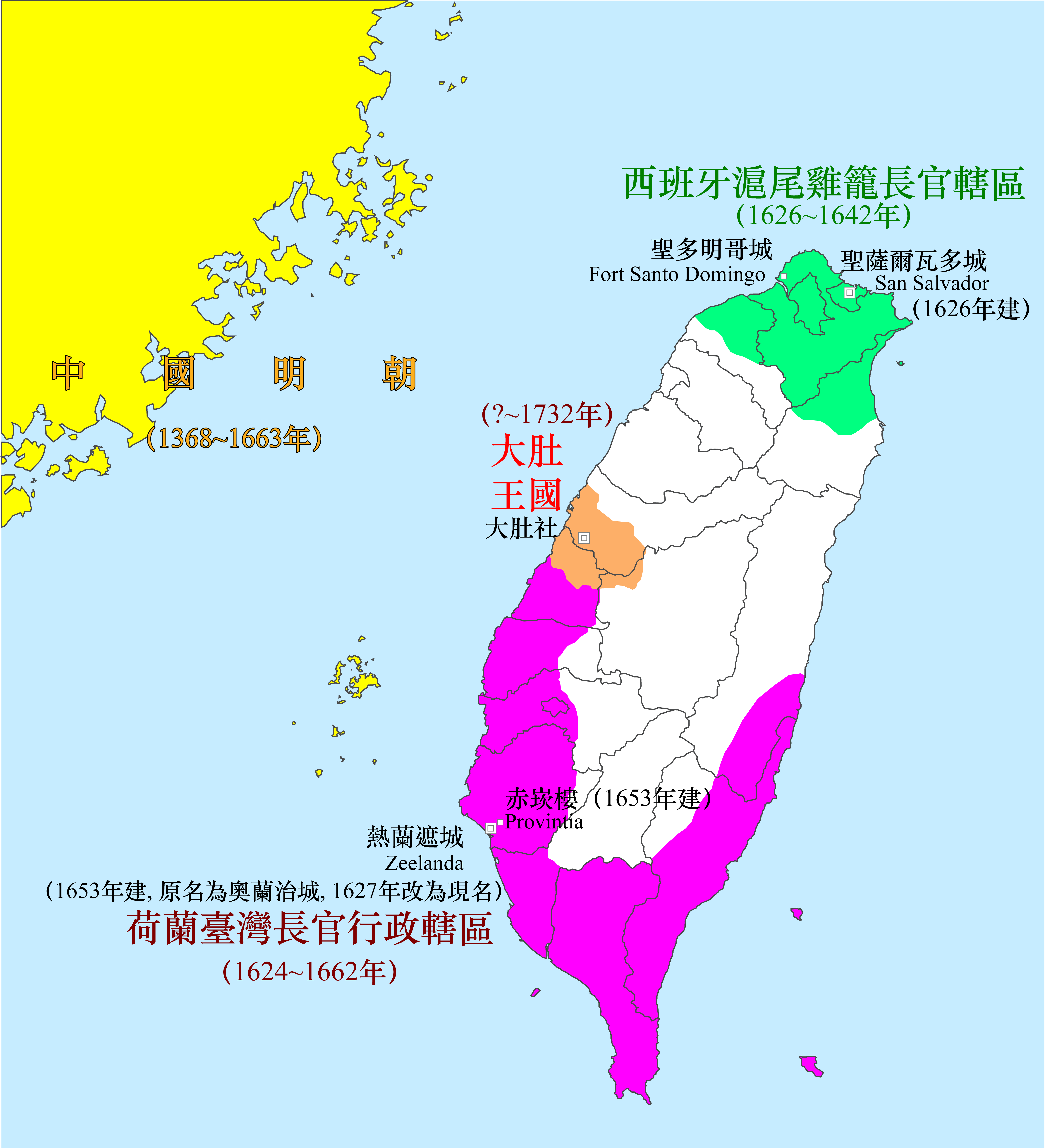

Dutch and Spanish colonies (1624–1668)

Contact and establishment

Portuguese sailors, passing Taiwan in 1544, first jotted in a ship's log the name of the island ''Ilha Formosa'', meaning "Beautiful Island". In 1582, the survivors of a Portuguese shipwreck spent 45 days battling

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

and aborigines before returning to

Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a p ...

on a raft. When they returned to Taiwan's southwestern coast in 1596, some of the crew members who had been shipwrecked in 1582 noticed that the land had been cultivated and now had people working it, presumably by Chinese settlers from Fujian.

The

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

(VOC) came to the area in search of an Asian trade and military base. Defeated by the Portuguese at the

Battle of Macau

The Battle of Macau in 1622 was a conflict of the Dutch–Portuguese War fought in the Portuguese settlement of Macau, in southeastern China. The Portuguese, outnumbered and without adequate fortification, managed to repel the Dutch in a much-ce ...

in 1622, they attempted to occupy

Penghu, but were

driven off by the Ming authorities in 1624. They then built

Fort Zeelandia on the islet of Tayowan off the southwest coast of Taiwan. The site is now part of the main island, in modern

Anping,

Tainan

Tainan (), officially Tainan City, is a special municipality in southern Taiwan facing the Taiwan Strait on its western coast. Tainan is the oldest city on the island and also commonly known as the "Capital City" for its over 200 years of his ...

. On the adjacent mainland, they built a smaller brick fort,

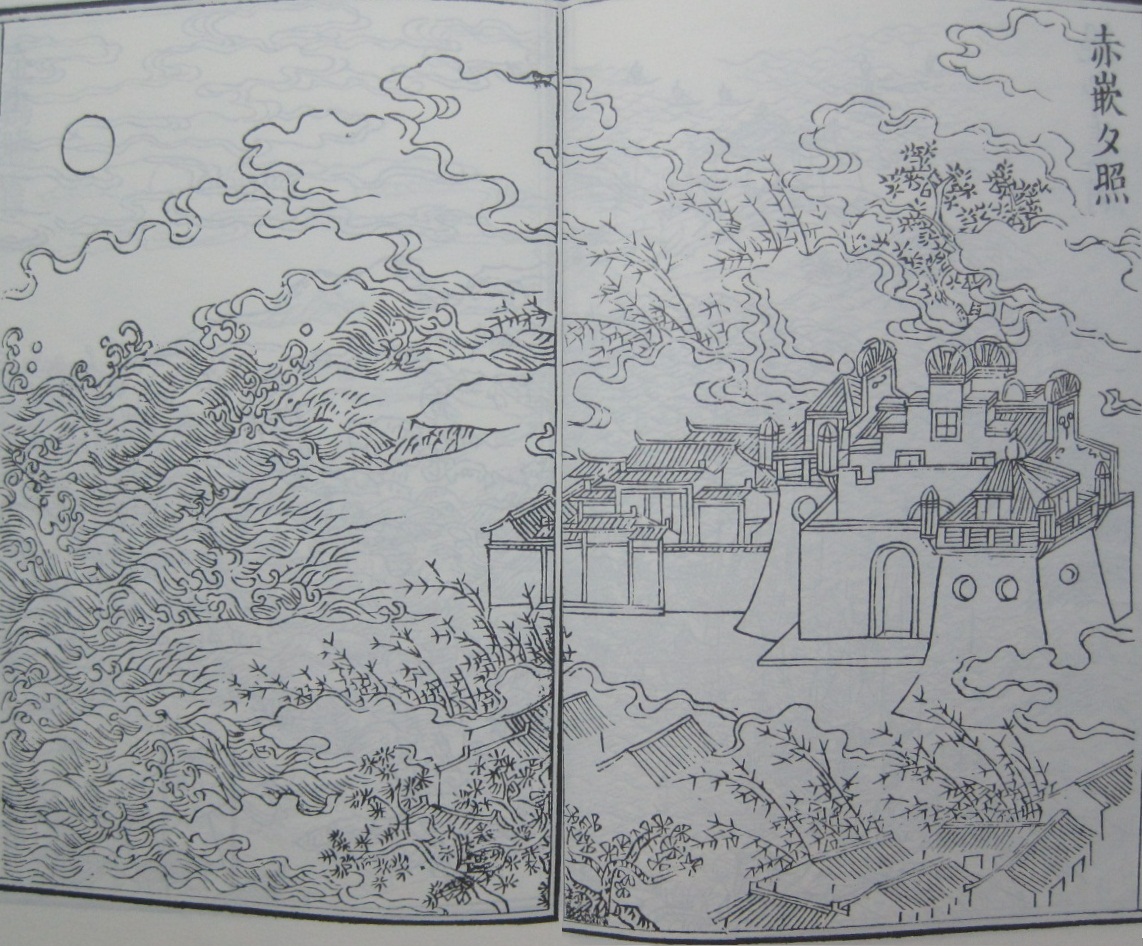

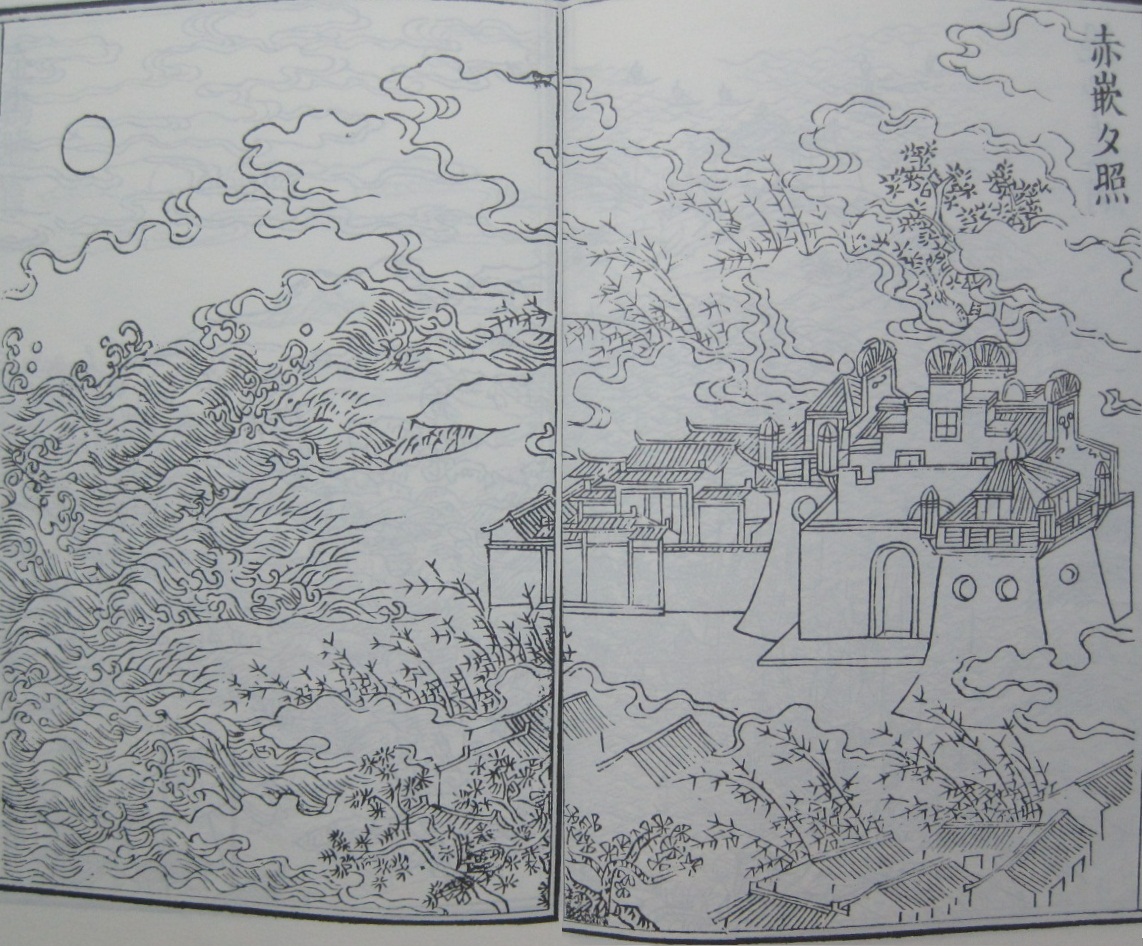

Fort Provintia. Local aboriginals called the area Pakan and on some old maps the island of Taiwan is named Pakan.

Piracy

The Europeans worked with and also fought against Chinese pirates. The pirate Li Dan was the mediator between Ming Chinese forces and the Dutch at Penghu. In 1625, VOC officials learned that he had kept gifts they had entrusted him with giving to Chinese officials. His men also tried pillaging junks on their way to trade in Taiwan. One Salvador Diaz acted as the pirates' informant and gave them inside information on where junks leaving Tayouan could be captured. Diaz collected protection money as well. A Chinese merchant named Xu Xinsu complained to Dutch officials that he was forced to pay 2,000 taels to Diaz. Li Dan's son, Li Guozhu, also collected collection money, known as "water taxes". Chinese fishermen paid 10 percent of their catch for a document guaranteeing their safety from pirates. This caused the VOC to also enter the protection business. They sent three junks to patrol a fishing fleet charging the same fee as the pirates, 10 percent of the catch. This was one of the first taxes the company levied on the colony.

In July 1626, the Council of Formosa ordered all Chinese living or trading in Taiwan to obtain a license to "distinguish the pirates from the traders and workers". This residence permit eventually became a head tax and major source of income for the Dutch.

Zheng Zhilong

After Li Dan died in 1625,

Zheng Zhilong

Zheng Zhilong, Marquis of Tong'an and Nan'an (; April 16, 1604 – November 24, 1661), baptismal name Nicholas Iquan Gaspard, was a Chinese admiral, merchant, military general, pirate, and politician of the late Ming dynasty who later defec ...

became the new pirate chief. The Dutch allowed him to pillage under their flag. In 1626, he sold a large junk to the company, and on another occasion he delivered nine captured junks as well as their cargos worth more than 20,000 taels. Chinese officials asked the Dutch for help against Zheng in return for trading rights. The company agreed and the Dutch lieutenant governor visited the officials in Fujian to inform them that the Dutch would drive Zheng from the coast. The Dutch failed and Zheng attacked the city of Xiamen, destroying hundreds of junks and setting fire to buildings and houses. In response, in 1628, the Chinese authorities awarded him with an official title and imperial rank. Zheng became the "Patrolling Admiral" responsible for clearing the coast of pirates. He used his official position to destroy his competitors and established himself in the port of Yuegang. In October 1628, Zheng agreed to supply silks, sugar, ginger, and other goods to the company in return for silver and spices at a fixed rate. Then the Dutch got angry at Zheng, who they were convinced was trying to monopolize trade to Taiwan. His promised "disappeared into smoke". In the summer of 1633, a Dutch fleet and the pirate Liu Xiang carried out a successful

sneak attack on Zheng's fleet. Zheng believed that he and the Dutch were on good terms and was caught off guard; his fleet was destroyed.

Zheng immediately began preparing a new fleet. On 22 October 1633, the Zheng forces lured the Dutch fleet and their pirate allies into an ambush and

defeated them. The Dutch reconciled with Zheng, who offered them favorable terms, and he arranged for more Chinese trade in Taiwan. The Dutch believed this was because of Chinese fears of piracy. The pirate Liu Xiang still fought against Zheng, and when the Dutch refused to help him, Liu captured a Dutch junk and used its 30-man crew as human shields. Liu attacked Fort Zeelandia but some Chinese residents warned the company and they fought off the pirates without any trouble. In 1637, Liu was defeated by Zheng, who established primacy over the Fujianese trading world. He continued to have a hand in the affairs of Taiwan and aided the growth of the Chinese population there. He made plans with a Chinese official to relocate drought victims to Taiwan and to provide each person three silver taels and an ox for every three people. The plan was never carried out.

Japanese trade

The Japanese had been trading for Chinese products in Taiwan since before the Dutch arrived in 1624. In 1593,

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

planned to incorporate Taiwan into his empire and sent an envoy with a letter demanding tribute. The letter was never delivered since there was no authority to receive it. In 1609, the

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

sent

Harunobu Arima on an exploratory mission of the island. In 1616,

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

official

Murayama Tōan sent 13 vessels to conquer Taiwan. The fleet was dispersed by a typhoon and the one junk that reached Taiwan was ambushed by headhunters, after which the expedition left and raided the Chinese coast instead.

In 1625, Batavia ordered the governor of Taiwan to prevent the Japanese from trading. The Chinese silk merchants refused to sell to the company because the Japanese paid more. The Dutch also restricted Japanese trade with the Ming dynasty. In response, the Japanese took on board 16 inhabitants from the aboriginal village of Sinkan and returned to Japan. Suetsugu Heizō Masanao housed the Sinkanders in Nagasaki. Batavia sent a man named

Peter Nuyts

Pieter Nuyts or Nuijts (born 1598 – 11 December 1655) was a Dutch explorer, diplomat and politician.

He was part of a landmark expedition of the Dutch East India Company in 1626–27 which mapped the southern coast of Australia. He became th ...

to Japan, where learned about the Sinkanders. The shogun declined to meet the Dutch and gave the Sinkanders gifts. Nuyts arrived in Taiwan before the Sinkanders and refused to allow them to land before the Sinkanders were jailed and their gifts confiscated. The Japanese took Nuyts hostage and only released him in return for their safe passage back to Japan with 200 picols of silk as well as the Sinkanders' freedom and the return of their gifts. The Dutch blamed the Chinese for instigating the Sinkanders.

The Dutch dispatched a ship to repair relations with Japan but it was seized and its crew imprisoned upon arrival. The loss of the Japanese trade made the Taiwanese colony far less profitable and the authorities in Batavia considered abandoning it before the Council of Formosa urged them to keep it unless they wanted the Portuguese and Spanish to take over. In June 1630, Suetsugu died and his son, Masafusa, allowed the company officials to reestablish communication with the shogun. Nuyts was sent to Japan as a prisoner and remained there until 1636 when he returned to the Netherlands. After 1635, the shogun forbade Japanese from going abroad and eliminated the Japanese threat to the company. The VOC expanded into previous Japanese markets in Southeast Asia. In 1639, the shogun ended all contact with the Portuguese, the company's major silver trade competitor.

Descriptions of Taiwan

Captain Ripon was a French-speaking

Swiss soldier from

Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR ...

. In 1617 he left for the Netherlands and initially served on a whaling expedition to Greenland before signing up for the Dutch East India Company. He was sent to Taiwan in 1623 to construct a fortress on the island. Shortly after finishing the fortress, Ripon was ordered to destroy the fortress and leave Taiwan. He wrote an account of his experiences.

Ripon's diary describes how he was sent to Tayouan where a small fortress was built. At the end of March 1624, Ripon's superiors ordered him to demolish the fortress, named Fort Oranje, and concentrate his forces at Penghu. On 30 July, the Ming navy reached the Dutch fort at Penghu with 5,000-10,000 soldiers and 40-50 warships and forced the Dutch to sue for peace on 3 August. The Dutch retreated to Tayouan and established a more permanent presence there. Ripon stayed behind to oversee the dismantling of the Penghu fortress. He left Penghu on 16 September. In Taiwan, Ripon was tasked with finding food. He had a falling out with the governor and left for Batavia in December.

According to Ripon, Taiwan looked like three mountains on top of each other with the highest covered in snow for three months a year. The streets of villages appeared narrow except at public squares at the center of which stood large round buildings. Men slept in these buildings and trained in the squares. He saw headhunting activity which occurred between the time of harvest until the next planting season. The heads of enemies were held in these men's houses, where a lamp burned at all times. They held celebrations in these places after returning from war. Successful head hunters were treated with reverence.

During his time in Taiwan, Ripon's party befriended the people of Bacaloan (modern

Tainan

Tainan (), officially Tainan City, is a special municipality in southern Taiwan facing the Taiwan Strait on its western coast. Tainan is the oldest city on the island and also commonly known as the "Capital City" for its over 200 years of his ...

) by giving them small gifts. They led him to the woods where he was free to gather lumber and in return Ripon gave them Indian fabrics. His friendship with Bacaloan angered the neighboring Mattau people who didn't receive the same gifts. Ripon described the Mattau people as quite tall, "like big giants." They attacked Ripon's party. He blamed the Chinese for inciting the natives against them. A few months later both the Bacaloan and Mattau people attacked the Dutch fortress. Three hundred tried to storm the fort by night but were repelled by cannon fire.

Other descriptions of the indigenous people of Taiwan note that raids and ambushes were the common way of warfare. It was convention for villages to officially declare war and to pay restitution for former raids. Alliances and peace were requested by sending weapons to the other side while sending gifts of trees meant submission. In 1630, Mattau built "a sturdy double wall around their village, the inside filled with clay, as well as a moat and many demi-lunes." Fortified villages seem to have been common in Taiwan until the 19th and 20th centuries. Besides villages, the Dutch also encountered a proto-state that was ruled by someone they referred to as the "Prince

orstof Lonkjouw." He ruled some 16 villages and their chiefs. Succession was hereditary.

Judging by Dutch sources, Taiwan's population was probably around 100,000 in this period, with a density of around 3 to 5 persons per square kilometer depending on the region. The southwestern plains was more densely populated. The low population density led to a higher nutritional diet. Europeans visiting Taiwan noted that the aborigines looked tall and healthy. There was an abundance of animal protein in the form of deer meat.

Spanish Formosa

In 1626, the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, viewing the Dutch presence on Taiwan as a threat to

their colony in the Philippines, established a settlement at

Santísima Trinidad on the northeast coast of Taiwan (modern

Keelung), building Fort San Salvador. They also built

Fort Santo Domingo

Fort Santo Domingo is a historical fortress in Tamsui District, New Taipei City, Taiwan. It was originally a wooden fort built in 1628 by the Spanish Empire, who named it "Fort Santo Domingo". However, the fort was then destroyed by the Spani ...

in the northwest (modern

Tamsui

Tamsui District (Hokkien POJ: ''Tām-chúi''; Hokkien Tâi-lô: ''Tām-tsuí''; Mandarin Pinyin: ''Dànshuǐ'') is a seaside district in New Taipei, Taiwan. It is named after the Tamsui River; the name means "fresh water". The town is popul ...

) in 1629 but abandoned it by 1638 due to conflicts with the local population. The small colony was plagued by disease and a hostile locals, and received little support from

Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, who viewed the fortresses as a drain on their resources.

In August 1641, the Dutch and their native allies tried to take the Spanish fortresses but they did not have enough artillery and left. August 1642, the Dutch ejected the Spanish from the north of the island.

Dutch colonization

According to Salvador Diaz, initially there were only 320 Dutch soldiers and they were "short, miserable, and very dirty." In 1624, the Dutch ship ''Golden Lion'' crashed into the coral reefs of

Liuqiu Island

Liuqiu, also known by #Names, several other names, is a coral island in the Taiwan Strait about southwest of the main island of Taiwan. It has an area of and approximately 13,000 residents, the vast majority of whom share only 10 Chinese s ...

and its crew was killed by the natives. In 1631, another ship wrecked on the reefs and its survivors were also killed by the inhabitants of Liuqiu Island. In 1633, an expedition consisting of 250 Dutch soldiers, 40 Chinese pirates, and 250 Taiwanese natives were sent against Liuqiu Island but met with little success.

The Dutch allied with Sinkan, a small village that provided them with firewood, venison and fish. In 1625, they bought a piece of land from the Sinkanders and built the town of

Sakam for Dutch and Chinese merchants. Initially the other villages maintained peace with the Dutch but a series of events from 1625 to 1629 eroded this peace. In 1625, the Dutch attacked 170 Chinese pirates in Wankan but were driven off, damaging their reputation. Encouraged by the Dutch failure, Mattau warriors raided Sinkan, believing that the Dutch could not defend them. The Dutch returned with their ships and drove off the pirates later, restoring their reputation. Mattau was then forced to return the property stolen from Sinkan and make reparation. The people of Sinkan then attacked Mattau and Baccluan before seeking the Dutch for protection. Feeling that the Dutch could not sufficiently protect them, the people of Sinkan went to Japan for protection. In 1629,

Pieter Nuyts

Pieter Nuyts or Nuijts (born 1598 – 11 December 1655) was a Dutch explorer, diplomat and politician.

He was part of a landmark expedition of the Dutch East India Company in 1626–27 which mapped the southern coast of Australia. He became t ...

visited Sinkan with 60 musketeers. After leaving the next morning, the musketeers were killed in an ambush by Mattau and Soulang warriors while crossing a stream. Nuyts avoided the ambush since he left the evening prior.

On 23 November 1629, an expedition set out and burned most of Baccluan, killing many of its people, who the Dutch believed harbored proponents of the previous massacre. Baccluan, Mattau, and Soulang people continued to harass company employees in the following years. This changed in late 1633 when Mattau and Soulang went to war with each other. Mattau won the fight but the Dutch were able to exploit the division.

In 1634, Batavia sent reinforcements. In 1635, 475 soldiers from Batavia arrived in Taiwan. By this point even Sinkan was on bad terms with the Dutch. Soldiers were sent into the village and arrested those who plotted rebellion. In the winter of 1635 the Dutch defeated Mattau, who had been troubling them since 1623. Baccluan, north of the town of Sakam, was also defeated. In 1636, a large expedition was sent against Liuqiu Island. The Dutch and their allies chased about 300 inhabitants into caves, sealed the entrances, and killed them with poisonous fumes over eight days. The native population of 1100 was removed from the island. They were enslaved with the men sent to Batavia while the women and children became servants and wives for the Dutch officers. The Dutch planned to depopulate the outlying islands while working closely with allied natives. The villages of Taccariang, Soulang, and Tevorang were also pacified. In 1642, the Dutch massacred the people of Liuqiu island again.

Administration

The Dutch estimated in 1650 that there were around 50,000 natives in the western plains region. According to documents in 1650, the Dutch Formosa ruled around "315 tribal villages with a total population of around 68,600, estimated 40-50% of the entire indigenes of the island". Taiwanese aboriginals were frequently employed as foot soldiers by the Dutch. The Dutch tried to convince the natives to give up hunting and adopt sedentary farming but their efforts were unsuccessful.

The VOC administered the island and its predominantly aboriginal population until 1662, setting up a tax system, schools to teach

romanized script of aboriginal languages and

evangelizing Christianity. The native Taiwanese religion was primarily

animist and considered sinful and less civilized. Practices like mandatory abortion, marital infidelity, nakedness, and non-observation of the

Christian Sabbath

Sabbath in Christianity is the inclusion in Christianity of a Sabbath, a day set aside for rest and worship, a practice that was mandated for the Israelites in the Ten Commandments in line with God's blessing of the seventh day (Saturday) making it ...

were also considered sinful. The Bible was translated into the native languages. This was the first entrance of Christianity into Taiwan. The missionaries set up schools in villages to teach Christianity, reading, and writing. The natives did not have a writing system so the missionaries created a number of romanization schemes for the various

Formosan languages

The Formosan languages are a geographic grouping comprising the languages of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, all of which are Austronesian. They do not form a single subfamily of Austronesian but rather nine separate subfamilies. The Taiwa ...

.

[ They tried to teach the native children the ]Dutch language

Dutch ( ) is a West Germanic language spoken by about 25 million people as a first language and 5 million as a second language. It is the third most widely spoken Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-Europea ...

but the effort was abandoned after failing to produce good results.

The Dutch levied a tax on all imports and exports. There are no records of the rates of such taxation. A tax was also levied on every non-Dutch person above the age of six. This poll tax was highly unpopular and the cause the major insurrections in 1640 and 1652. A tax was imposed on hunting through licenses to dig pit-traps and for snaring.[Huang, C 2011, 'Taiwan under the Dutch' in A new history of Taiwan, The Central News Agency, Taipei, p. 71.] Although its control was mainly limited to the western plain of the island, the Dutch systems were adopted by succeeding occupiers.

The Dutch originally sought to use their castle Zeelandia at Tayowan as a trading base between Japan and China, but soon realized the potential of the huge deer populations that roamed in herds of thousands along the alluvial plains of Taiwan's western regions.

Chinese settlers

The VOC encouraged Chinese migration to Taiwan. The Dutch colony provided a military and administrative structure for Chinese immigration. It advertised to the Chinese through coastal entrepreneurs free land, freedom from taxes, the use of oxen, and loans. Sometimes they even paid the Chinese to move to Taiwan. As a result, thousands of Chinese crossed the strait and became rice and sugar planters. The Chinese settlers were of Hakka and Hokkien stock during the Dutch period. Most of them were young single men seeking to hide from Qing authorities or to hunt in Taiwan. They referred to Taiwan as ''The Gate of Hell'' for its reputation in taking the lives of sailors and explorers.

In 1625, the company started advertising Provintia to the Chinese as a site of settlement. The next year the town caught fire and shortly afterward it was beset by fever. The Chinese all fled and all the company employees grew sick. The company withdrew personnel from the town and destroyed the fortress. In 1629, the natives of Mattau and Soulang attacked Sakam and chased away the inhabitants of Provintia. In 1632, the company began encouraging Chinese to plant sugarcane in Sakam by providing them money and cattle. The efforts came to fruition and by 1634 there was sugar "as white as that of China." By 1635, Chinese entrepreneurs were preparing for larger plantations. In the spring, 300 Chinese laborers arrived. The Chinese also cultivated rice but access to water was difficult and by 1639 the Chinese had lost their desire to plant rice. This problem was addressed in the early 1640s and rice production began to grow again. Other industries began to spring up: butchers, blacksmiths, coopers, carpenters, curriers, cobblers, masons, tailors among them. In the 1640s the Dutch began to tax them, reaping large benefits, causing some Chinese to become discontent. After 1648, nearly all company revenue came from the Chinese.

The Chinese were allowed property rights in a limited area and the Dutch made efforts to prevent the Chinese from mingling with the natives. Initially the company policy was to protect the Chinese from the natives but later the policy shifted to trying to keep Chinese from influencing the natives. The native people traded meat and hides for salt, iron, and clothing from Chinese traders who sometimes stayed in their villages. In the interior, deer skins were traded by the aborigines. In 1634 the Dutch ordered the Chinese to sell deerskins to no one but the company since the Japanese offered better prices. By 1636, Chinese hunters were entering previously native-lands where the Dutch had removed the natives to greater profit from the deer economy. Commercial hunters replaced the natives and used the pitfall to increase deer products. By 1638 the future of the deer population was being questioned. Restrictions were put on hunting periods but this proved insufficient so the use of the pitfall was also restricted.

In 1636, Favorolang, the largest aboriginal village north of Mattau, killed three Chinese and wounded several others while harassing Chinese hunters and fishers. In August a large band of Favorolangers appeared at Wankan north of Fort Zeelandia. In November the Favorolangers captured a Chinese fishing vessel. The next year the Dutch and their native allies defeated Favorolang. The expedition was paid for by the Chinese populace. When peace negotiations failed, the Dutch blamed a group of Chinese at Favorolang. The Favorolangers continued to attack hunters even in fields belonging to other villages until 1638. In 1640 an incident involving the capture of a Favorolang leader and the ensuing death of three Dutch hunters near Favorolang resulted in the banning of Chinese hunters from Favorolang territory. The Dutch blamed the Chinese and orders were given from Batavia to restrict Chinese residency and travel. No Chinese vessel was allowed around Taiwan unless it carried a company license. An expedition was ordered to chase away the Chinese from the land and to subjugate the natives to the north. In November 1642, an expedition set out northward, killing 19 natives and 11 Chinese, and executing the Chinese and natives responsible for the murder of three Dutchmen. A policy banning any Chinese from living north of Mattau was implemented. In 1644 the Chinese were allowed to live in Favorolang to conduct trade if they purchased a permit. The Favorolangers were told that the Chinese "were despicable people uyle menschenwho sought to instill in them false opinions of us he Dutch and to capture any Chinese who did not possess a permit.

In the late 1630s, officials in Batavia started pressuring the authority in Taiwan to increase revenues. The Dutch started collecting voluntary donations from the Chinese but these donations were not reliable. In addition to a 10 percent tax on venison, beer, salt, mullet, arrack, bricks and mortar, and real estate sales, they also implemented a residency-permit tax (hoofdbrieven). In August and September 1640, some 3,568 Chinese were charged a quarter of a real per month, increasing to some 4,450 Chinese payments on average. All male Chinese were taxed for residency. Checks were made by soldiers at inspection points so that the Chinese could not move to another village without permission. Any transgression could be punished with a fine, beating, or imprisonment. Chinese settlers began protesting the residency tax, that the Dutch harassed them on roads for pay. In 1646, the Council informed the Chinese that they only had to answer to specific officials, however complaints continued. According to a report, "soldiers not only confiscate their hoofdbrieven, in order to prosecute them and demand a fine, but also take their meager possessions, seizing anything they can get their hands on, whether chickens, pigs, rice, clothing, bedding, or furniture.

The Dutch also auctioned off the collection of taxes for rice farming and sold the right to trade with aboriginal villages. However the Dutch thought the Chinese were exploiting the natives by selling at high prices: "for the Chinese . . . are even more deceptive and deceitful than the Jews, and will not sell their goods . . . for a more civil price unless he companystopped selling leases altogether." The sale of rights to trade with aborigines was not just a way to raise profits but to keep track of the Chinese and prevent them from mingling with the natives. Policing the rights to trade in aboriginal villages and alterations to the system eventually caused the reputation of the company to drop, gaining for them a reputation of tyranny.

Chinese rebellions

In the late 1640s, increased population, higher rice prices, and Dutch taxes pressured the Chinese population into violence. In 1643, a pirate named Kinwang began attacking aboriginal villages. For several months Kinwang and his followers sailed around Taiwan attacking inland aboriginal villages. In 1644 his junk stranded in the Bay of Lonkjauw and the natives captured him, handing him over to the Dutch. Although he was executed, a document in his possession was found appealing to the Chinese who chaffed under Dutch taxes and their restrictions on trading and hunting. The document said the pirates would protect them and kill any natives who sought to harm them.

On 7 September 1652, it was reported that a Chinese farmer, Guo Huaiyi, had gathered an army of peasants armed with bamboo spears and harvest knives to attack Sakam. They attacked the next morning. Most of the Dutch were able to find refuge in the company's horse stables but others were captured and executed. A company of 120 Dutch soldiers shot at a peasant army 4,000 strong and scattered them. The Dutch told the natives that they would be rewarded with Indian textiles if they helped fight the Chinese. Over the next two days, native warriors and Dutch warriors killed around 500 Chinese, most of whom were hiding in the sugarcane fields. On 11 September, four or five thousand Chinese rebels clashed with the company soldiers and their native allies. After suffering two thousand casualties, the rebels fled south, only to be killed by a large force of natives. In total some 4,000 Chinese were killed and Guo Huaiyi's head was displayed on a stake.

Although easily put down, the rebellion and its ensuing massacre of Chinese destroyed the rural labor force since most of the rebels were farmers. Although the crops were fairly unharmed, the company could not obtain the required labor to harvest them, resulting in a below average harvest for 1653. However thousands of Chinese migrated to Taiwan due to war on the mainland and a modest recovery of agriculture occurred the next year. Measure were taken to suppress the Chinese and anti-Chinese rhetoric increased. Natives were reminded to keep an eye on the Chinese and not to engage in unnecessary contact with them. The Dutch portrayed themselves as protectors of aboriginal land against Chinese encroachment. In terms of military preparations, little was done except to build a small thinly walled fort. The Dutch did not feel threatened because most of the rebels were agriculturalists while the rich Chinese had sided with the Dutch and warned them of the rebellion.

In May 1654, Fort Zeelandia was afflicted by a swarm of locusts, then a plague that killed thousands of natives, Dutch, and Chinese, and then an earthquake that destroyed homes and buildings with aftershocks lasting seven weeks.

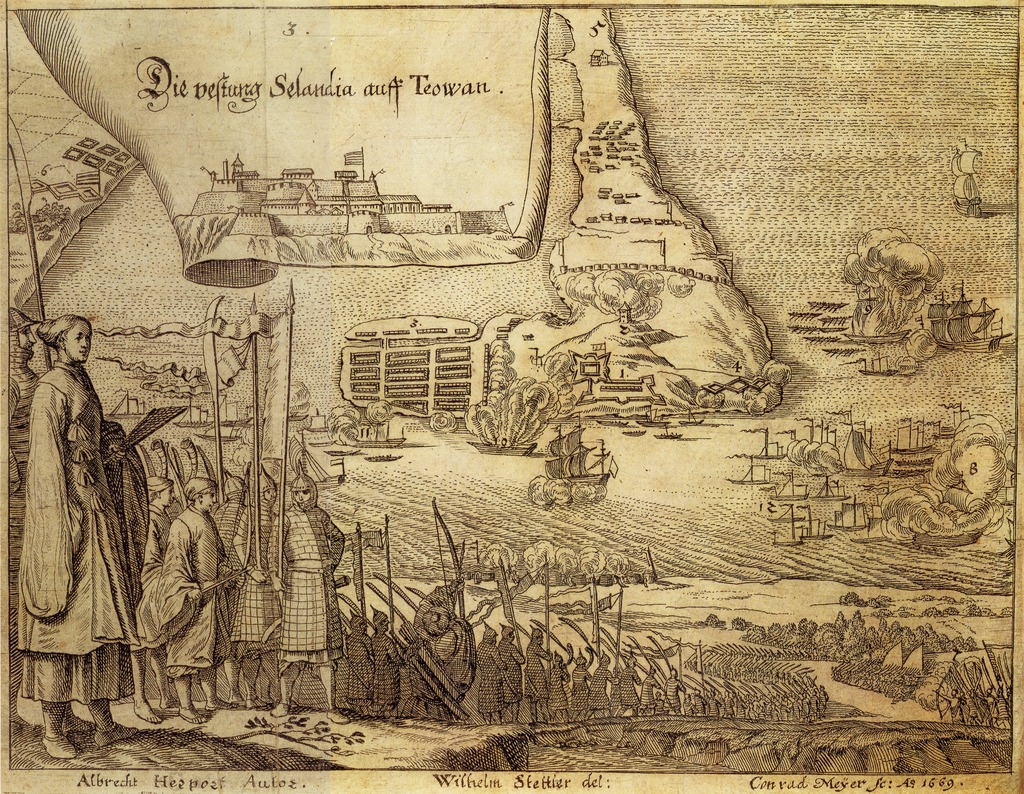

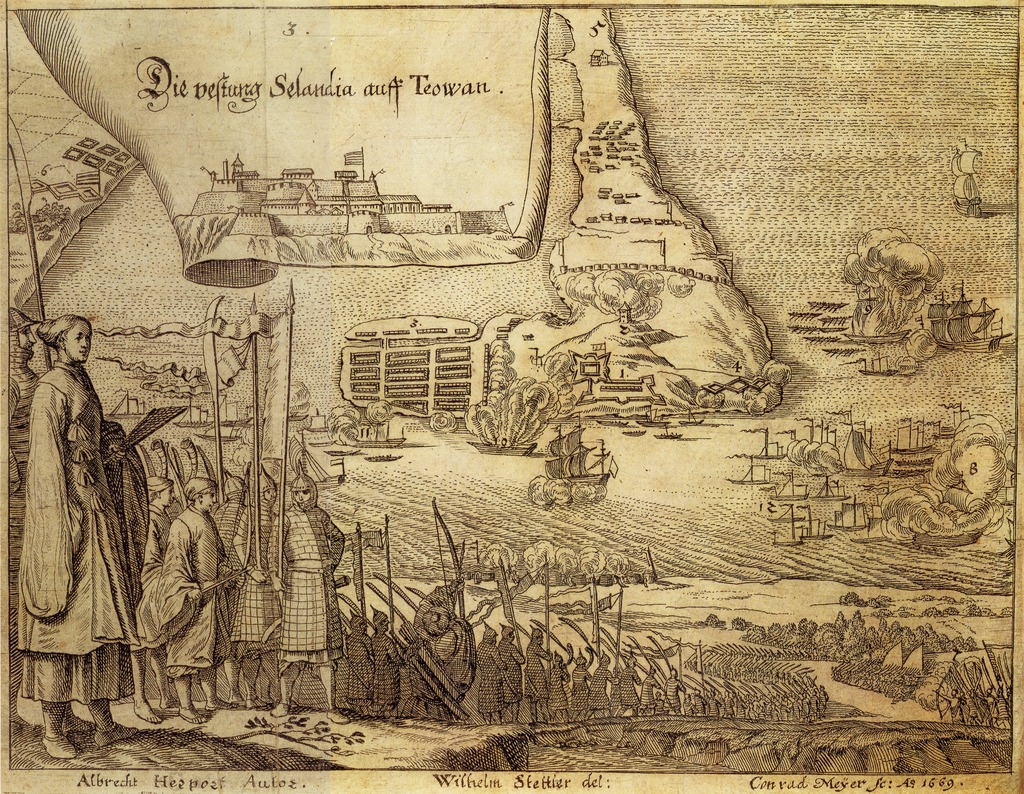

Zheng Chenggong

Ming-Qing war

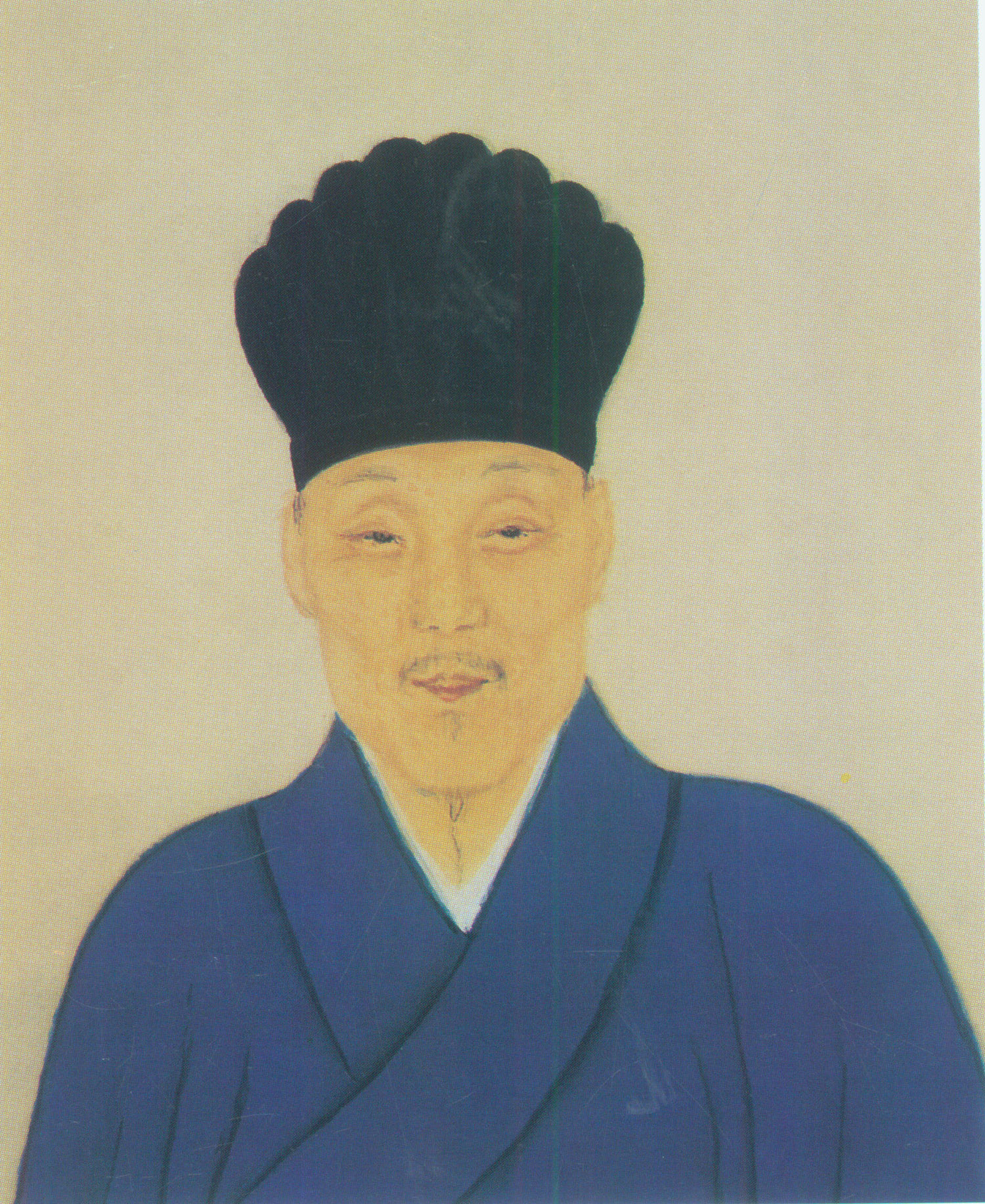

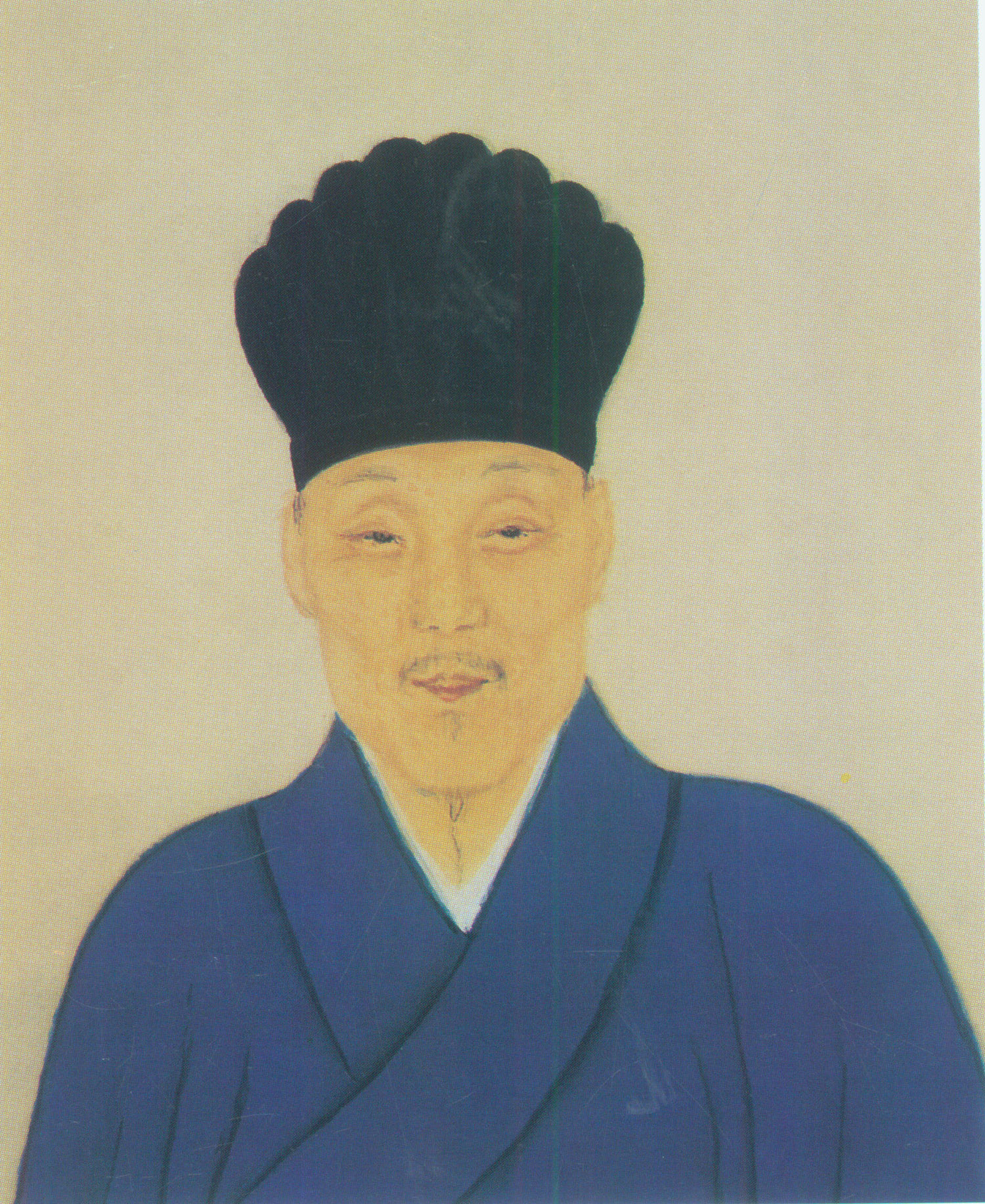

Zheng Chenggong

Zheng Chenggong, Prince of Yanping (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), better known internationally as Koxinga (), was a Ming loyalist general who resisted the Qing conquest of China in the 17th century, fighting them on China's southeastern ...

, known in Dutch sources as Koxinga, was the son of Zheng Zhilong

Zheng Zhilong, Marquis of Tong'an and Nan'an (; April 16, 1604 – November 24, 1661), baptismal name Nicholas Iquan Gaspard, was a Chinese admiral, merchant, military general, pirate, and politician of the late Ming dynasty who later defec ...

. By 1640, Zhilong had become military commander of Fujian Province

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

. He spent the first seven years of his life in Japan with his mother and then went to school in Fujian, obtaining a county-level licentiate at the age of 15. Afterwards he left for Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

to study at the Imperial Academy. After Beijing fell in 1644 to rebels, Chenggong and his followers declared their loyalty to the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

and he was bestowed the title Guoxingye, or Lord of the Imperial surname, pronounced "Kok seng ia" in southern Fujianese, from which Koxinga is derived. His father Zhilong aided the Longwu Emperor

Zhu Yujian (; 1602 – 6 October 1646), nickname Changshou (長壽), originally the Prince of Tang, later reigned as the Longwu Emperor () of the Southern Ming from 18 August 1645, when he was enthroned in Fuzhou, to 6 October 1646, when he wa ...

in a military expedition in 1646, but Longwu was captured and executed. In November 1646, Zhilong declared his loyalty to the Qing and lived out the rest of his life under house arrest in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

. Chenggong continued the resistance against the Qing from Xiamen

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong'an ...

, which was named "Memorial Prefecture for the Ming" in 1654. In 1649, Chenggong gained control over Quanzhou but then lost it. Further attacks further afield resulted in even less success. In 1650 he planned a major northward offensive from Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

in conjunction with a Ming loyalist in Guangxi. The Qing deployed a large army to the area and Chenggong decided to take his chances by ferrying his army along the coast but a storm hindered his movements. The Qing launched a surprise attack on Xiamen, forcing him to return to protect it. From 1656 to 1658 he planned to take Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

. In the summer of 1658 he completed his preparations and set sail with his fleet but a storm turned him back. On July 7, 1659, Chenggong's fleet set sail again and his army encircled Nanjing on 24 August. Qing reinforcements arrived and broke Chenggong's army, forcing them to retreat to Xiamen with many of the veterans and thousands of soldiers killed or captured. In 1660 the Qing embarked on a coastal evacuation policy to starve Chenggong of his source of livelihood.

Trade war

Chenggong had cordial relations with the VOC during most of the 1640s and early 1650s. However some of the rebels during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion had expected Chenggong to come to their aid. Some company officials believed that the rebellion had been inciteded by Chenggong. A Jesuit priest told the Dutch that Chenggong was looking at Taiwan as a new base of operations. In 1654, he sent a letter to Taiwan to have a Dutch surgeon sent to Xiamen for medical assistance. In the spring of 1655 no silk junks arrived in Taiwan. Company officials suspected that this was caused by the Ming-Qing war but others felt it was a deliberate plan by Chenggong to cause them harm. The company sent a junk to Penghu to see whether Chenggong was preparing forces there but they found nothing. Defenses at Fort Zeelandia were strengthened. According to European and Chinese traders, Chenggong had 300,000 men and 3,000 junks. In 1655, the governor of Taiwan received a letter from Chenggong insulting the Dutch, calling them "more like animals than Christians," and referring to the Chinese in Taiwan as his subjects. He commanded them to stop trading with the Spanish. Chenggong sent a letter directly to the Chinese leaders in Taiwan, rather than Dutch authorities, stating that he would withhold his junks from trading in Taiwan if the Dutch would not guarantee his junks safety from Dutch depredations in Southeast Asia. To raise funds for his war effort, Chenggong had increased foreign trade by sending junks to Japan, Tonkin, Cambodia, Palembang, and Malaka. Batavia was wary of this competition and wrote that this would "undermine our profits." Batavia sent a small fleet to Southeast Asian ports to intercept Chenggong's junks. One junk was captured and its cargo of peppers confiscated but another junk managed to escape. The Dutch realized this would be received badly by Chenggong and thus offered an alliance with the

Chenggong had cordial relations with the VOC during most of the 1640s and early 1650s. However some of the rebels during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion had expected Chenggong to come to their aid. Some company officials believed that the rebellion had been inciteded by Chenggong. A Jesuit priest told the Dutch that Chenggong was looking at Taiwan as a new base of operations. In 1654, he sent a letter to Taiwan to have a Dutch surgeon sent to Xiamen for medical assistance. In the spring of 1655 no silk junks arrived in Taiwan. Company officials suspected that this was caused by the Ming-Qing war but others felt it was a deliberate plan by Chenggong to cause them harm. The company sent a junk to Penghu to see whether Chenggong was preparing forces there but they found nothing. Defenses at Fort Zeelandia were strengthened. According to European and Chinese traders, Chenggong had 300,000 men and 3,000 junks. In 1655, the governor of Taiwan received a letter from Chenggong insulting the Dutch, calling them "more like animals than Christians," and referring to the Chinese in Taiwan as his subjects. He commanded them to stop trading with the Spanish. Chenggong sent a letter directly to the Chinese leaders in Taiwan, rather than Dutch authorities, stating that he would withhold his junks from trading in Taiwan if the Dutch would not guarantee his junks safety from Dutch depredations in Southeast Asia. To raise funds for his war effort, Chenggong had increased foreign trade by sending junks to Japan, Tonkin, Cambodia, Palembang, and Malaka. Batavia was wary of this competition and wrote that this would "undermine our profits." Batavia sent a small fleet to Southeast Asian ports to intercept Chenggong's junks. One junk was captured and its cargo of peppers confiscated but another junk managed to escape. The Dutch realized this would be received badly by Chenggong and thus offered an alliance with the Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and ...

in Beijing, however nothing came of the negotiations.

The Taiwanese trade slowed and for several months in late 1655 and early 1656 not a single Chinese vessel arrived in Tayouan. Even low-cost goods grew scarce and as demand for them rose, the value of aboriginal products fell. Chinese merchants in Taiwan suffered because they could not take their products to China to sell. The system of selling Chinese merchants the right to trade in aboriginal villages fell apart as did many of the other revenue systems supporting the company's profits. On 9 July 1656, a junk flying Chenggong's flag arrived at Fort Zeelandia. It carried an edit instructed to be handed over to the Chinese leaders of Taiwan. Chenggong wrote that he was angry with the Dutch but since Chinese people lived in Taiwan, he would allow them to trade on the Chinese coast for 100 days so long as only Taiwanese products were sold. The Dutch confiscated the letter but the damage had been done. Chinese merchants who depended on trade of foreign wares began leaving with their families. Chenggong made good on his edict and confiscated a Chinese junk from Tayouan trading pepper in Xiamen, causing Chinese merchants to abort their trade voyages. A Chinese official arrived in Tayouan carrying a document with Chenggong's seal demanding to inspect all the junks in Tayouan and their cargoes. It referred to the Chinese in Taiwan as his subjects. Chinese merchants refused to buy the company's foreign wares and even sold their own foreign wares, causing prices to collapse. Soon, Tayouan was devoid of junks.