History of Sudan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Sudan refers to both the territory of the Republic of the Sudan, including what became in 2011 the independent state of

The history of Sudan refers to both the territory of the Republic of the Sudan, including what became in 2011 the independent state of

Sudan A Country Study

. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991. During the fifth millennium BCE, migrations from the drying

Northern Sudan's earliest historical record comes from ancient Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream as ''Kush''. For more than two thousand years, the

Northern Sudan's earliest historical record comes from ancient Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream as ''Kush''. For more than two thousand years, the  Around 1720 BC,

Around 1720 BC,

On the turn of the fifth century, the

On the turn of the fifth century, the  From the mid 8th-mid 11th century Christian Nubia went through its

From the mid 8th-mid 11th century Christian Nubia went through its

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the  The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the

In 1896, a Belgian expedition claimed portions of southern Sudan that became known as the Lado Enclave. The Lado Enclave was officially part of the

In 1896, a Belgian expedition claimed portions of southern Sudan that became known as the Lado Enclave. The Lado Enclave was officially part of the

In February 1953, the

In February 1953, the

An agreement for the restoration of harmony between Chad and Sudan, signed January 15, 2010, marked the end of a five-year war between them. The Sudanese government and the JEM signed a ceasefire agreement ending the Darfur conflict in February, 2010.

In January 2011, a referendum on independence for Southern Sudan was held, and the South voted overwhelmingly to secede later that year as the Republic of South Sudan, with its capital at Juba and Kiir Mayardit as its first president. Al-Bashir announced that he accepted the result, but violence soon erupted in the disputed region of

An agreement for the restoration of harmony between Chad and Sudan, signed January 15, 2010, marked the end of a five-year war between them. The Sudanese government and the JEM signed a ceasefire agreement ending the Darfur conflict in February, 2010.

In January 2011, a referendum on independence for Southern Sudan was held, and the South voted overwhelmingly to secede later that year as the Republic of South Sudan, with its capital at Juba and Kiir Mayardit as its first president. Al-Bashir announced that he accepted the result, but violence soon erupted in the disputed region of

Europe External Programme with Africa An EEPA report stated that on 18 December 2020, the Sudanese government has accused the Ethiopian government of using artillery against Sudanese troops conducting operations in the border area. Tensions have been rising between the two countries in recent weeks after Sudan reoccupied land that it said was occupied by Ethiopian farmers. The government of Ethiopia has so far not commented on the matter. On 18 December 2020, Sudanese authorities were instructing recently arrived Tigrayan refugees in Hamadyat camp to dismantle and go to the mainland of Sudan in fear of potential war between Ethiopia and Sudan. On 19 December 2020, tension between Ethiopia and Sudan was increasing. Sudan has sent more troops, including Rapid Support Forces, and equipment to the border area. Support from the

Europe External Programme with Africa On 20 December 2020, the Sudanese army had regained control of Jabal Abu Tayyur, in the disputed land on the Ethiopia-Sudan border. Heavy fighting broke out between the Sudanese military and the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) and Amhara militia in Metemma near the Ethiopian-Sudanese border.

Photographs from the Sudan

LIFE Visits Sudan in 1947

– slideshow by ''

South Sudan: A History of Political Domination – A Case of Self-Determination, (Riek Machar)

excerpt and text search

* * Vezzadini, Elena, Seri-Hersch, I., Revilla, L., Poussier, A. and Abdul Jalil, M. (2023). ''Ordinary Sudan, 1504–2019: From Social History to Politics from Below: Volume 1: Towards a New Social History of Sudan. Volume 2: Power from Below – Ordinary doing and undoing of the Establishment''. Berlin: De Gruyter. * Warburg, Gabriel. ''Sudan Under Wingate: Administration in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1916)'' (1971) * Woodward, Peter. ''Sudan 1898–1989 the Unstable State'' (1990) * Woodward, Peter, ed. ''Sudan After Nimeiri'' (2013); since 198

excerpt and text search

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Sudan

South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of th ...

. The territory of Sudan is geographically part of a larger African region, also known by the term "Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

". The term is derived from ar, بلاد السودان ''bilād as-sūdān'', or "land of the black people", and has sometimes been used more widely referring to the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

belt of West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

and Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Co ...

.

The modern Republic of the Sudan was formed in 1956 and inherited its boundaries from Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

, established in 1899. For times predating 1899, usage of the term "Sudan" mainly applied to the Turkish Sudan and the Mahdist State, and a wider and changing territory between Egypt in the North and regions in the South adjacent to modern Uganda, Kenia and Ethiopia.

The early history of the Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush (; Egyptian: 𓎡𓄿𓈙 𓈉 ''kꜣš'', Assyrian: ''Kûsi'', in LXX grc, Κυς and Κυσι ; cop, ''Ecōš''; he, כּוּשׁ ''Kūš'') was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in wh ...

, located along the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

region in northern Sudan, is intertwined with the history of ancient Egypt

The history of ancient Egypt spans the period from the early prehistoric settlements of the northern Nile valley to the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The pharaonic period, the period in which Egypt was ruled by a pharaoh, is dated from the ...

, with which it was politically allied over several regnal eras. By virtue of its proximity to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Sudan participated in the wider history of the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

, with the important 25th dynasty of Egypt and the Christianization of the three Nubian kingdoms Nobatia, Makuria

Makuria (Old Nubian: , ''Dotawo''; gr, Μακουρία, Makouria; ar, المقرة, al-Muqurra) was a Nubians, Nubian monarchy, kingdom located in what is today Northern Sudan and Southern Egypt. Makuria originally covered the area along the N ...

and Alodia

Alodia, also known as Alwa ( grc-gre, Aρουα, ''Aroua''; ar, علوة, ''ʿAlwa''), was a medieval kingdom in what is now central and southern Sudan. Its capital was the city of Soba, located near modern-day Khartoum at the confluence of t ...

in the sixth century. As a result of Christianization, the Old Nubian language stands as the oldest recorded Nilo-Saharan language (earliest records dating to the eighth century in an adaptation of the Coptic alphabet

The Coptic alphabet is the script used for writing the Coptic language. The repertoire of glyphs is based on the Greek alphabet augmented by letters borrowed from the Egyptian Demotic and is the first alphabetic script used for the Egyptian ...

).

While Islam was already present on the Sudanese Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

coast and the adjacent territories since the 7th century, the Nile Valley did not undergo Islamization

Islamization, Islamicization, or Islamification ( ar, أسلمة, translit=aslamāh), refers to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occurr ...

until the 14th-15th century, following the decline of the Christian kingdoms. These kingdoms were succeeded by the Sultanate of Sennar in the early 16th century, which controlled large parts of the Nile Valley and the Eastern Desert, while the kingdoms of Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju ...

controlled the western part of Sudan. Two small kingdoms arose in the southern regions, the Shilluk Kingdom of 1490, and Taqali of 1750, near modern-day South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of th ...

, but both northern and southern regions were seized by Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, also known as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and the Sudan ( sq, Mehmet Ali Pasha, ar, محمد علي باشا, ; ota, محمد علی پاشا المسعود بن آغا; ; 4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849), was ...

during the 1820s. The oppressive rule of Muhammad Ali and his immediate successors is credited for stirring up resentment against the Turco-Egyptian and British rulers and led to the establishment of the Mahdist State, founded by Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, ...

in 1881.

Since independence in 1956, the history of Sudan has been plagued by internal conflict, such as the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972), the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005), the War in Darfur

The War in Darfur, also nicknamed the Land Cruiser War, is a major armed conflict in the Darfur region of Sudan that began in February 2003 when the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebel groups beg ...

(2003–2010), culminating in the secession of South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of th ...

on 9 July 2011.

Prehistory

Nile Valley

By the eighth millennium BCE, people of aNeolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mud-brick

A mudbrick or mud-brick is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of loam, mud, sand and water mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE, though since 4000 BCE, bricks have also been f ...

villages, where they supplemented hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

and fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from fish stocking, stocked bodies of water such as fish pond, ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. ...

on the Nile with grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit ( caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legum ...

gathering and cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

herding."Early History", Helen Chapin Metz, edSudan A Country Study

. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991. During the fifth millennium BCE, migrations from the drying

Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

brought neolithic people into the Nile Valley along with agriculture. The population that resulted from this cultural and genetic mixing developed social hierarchy over the next centuries become the Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush (; Egyptian: 𓎡𓄿𓈙 𓈉 ''kꜣš'', Assyrian: ''Kûsi'', in LXX grc, Κυς and Κυσι ; cop, ''Ecōš''; he, כּוּשׁ ''Kūš'') was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in wh ...

(with the capital at Kerma

Kerma was the capital city of the Kerma culture, which was located in present-day Sudan at least 5,500 years ago. Kerma is one of the largest archaeological sites in ancient Nubia. It has produced decades of extensive excavations and research, ...

) at 1700 BCE. Anthropological and archaeological research indicate that during the pre-dynastic period Lower Nubia and Magadan Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient E ...

were ethnically, and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of Pharaonic kingship by 3300 BCE. Together with other countries on Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

, Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

is considered the most likely location of the land known to the ancient Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

as '' Punt'' (or "Ta Netjeru", meaning "God's Plan"), whose first mention dates to the 10th century BCE.

Eastern Sudan

In eastern Sudan, the Butana Group appears around 4000 BC. These people produced simple decorated pottery, lived in round huts and were most likely herdsmen, hunters, but also consumed land snails and there is evidence for some agriculture. The Gash Group started around 3000 BC and is another prehistory culture known from several places. These people produced decorated pottery and lived from farming and cattle breeding. Mahal Teglinos was an important place about 10 hectare large. In the center were excavated mud brick built houses. Seals and seal impressions attest a higher level of administration. Burials in an elite cemetery were marked with rough tomb stones. In the second millennium followed the Jebel Mokram Group. They produced pottery with simple incised decoration and lived in simple round huts. Cattle breeding was most likely the economical base.Antiquity

Kingdom of Kush

Northern Sudan's earliest historical record comes from ancient Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream as ''Kush''. For more than two thousand years, the

Northern Sudan's earliest historical record comes from ancient Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream as ''Kush''. For more than two thousand years, the Old Kingdom of Egypt

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

( 2700–2180 BC) had a dominating and significant influence over its southern neighbour, and even afterward, the legacy of Egyptian cultural and religious introductions remained important.

Over the centuries, trade developed. Egyptian caravans carried grain to Kush and returned to Aswan with ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

, incense

Incense is aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremony. It may also b ...

, hides, and carnelian (a stone prized both as jewellery

Jewellery ( UK) or jewelry ( U.S.) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a w ...

and for arrowheads) for shipment downriver. Egyptian governors particularly valued gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

in Nubia and soldiers in the pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

's army. Egyptian military expeditions penetrated Kush periodically during the Old Kingdom. Yet there was no attempt to establish a permanent presence in the area until the Middle Kingdom (c. 2100–1720 BC), when Egypt constructed a network of forts along the Nile as far south as Samnah in Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, ...

to guard the flow of gold from mines in Wawat, the area between the First and Second Cataracts.

Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ite nomads called the Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC).

T ...

took over Egypt, ended the Middle Kingdom, severed links with Kush, and destroyed the forts along the Nile River. To fill the vacuum left by the Egyptian withdrawal, a culturally distinct indigenous Kushite kingdom emerged at al-Karmah, near present-day Dongola. After Egyptian power revived during the New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

(c. 1570–1100 BC), the pharaoh Ahmose I incorporated Kush as an Egyptian ruled province governed by a viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

. Although Egypt's administrative control of Kush extended only down to the Fourth Cataract, Egyptian sources list tributary districts reaching to the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

and upstream to the confluence of the Blue Nile

The Blue Nile (; ) is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It travels for approximately through Ethiopia and Sudan. Along with the White Nile, it is one of the two major tributaries of the Nile and supplies about 85.6% of the water to ...

and White Nile

The White Nile ( ar, النيل الأبيض ') is a river in Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile, the other being the Blue Nile. The name comes from the clay sediment carried in the water that changes the water to a pale color ...

rivers. Egyptian authorities ensured the loyalty of local chiefs by drafting their children to serve as pages at the pharaoh's court. Egypt also expected tribute in gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

and workers from local Kushite chiefs.

Once Egypt had established political and military mastery over Kush, officials, priests, merchants, and artisans settled in the region. The Egyptian language

The Egyptian language or Ancient Egyptian ( ) is a dead Afro-Asiatic language that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts which were made accessible to the modern world following the deciphe ...

became widely used in everyday activities. Many rich Kushites took to worshipping Egyptian gods and built temples for them. The temples remained centres of official religious worship until the coming of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

to the region during the sixth century. When Egyptian influence declined or succumbed to foreign domination, the Kushite elite regarded themselves as central powers and believed themselves as idols of Egyptian culture and religion.

By the 11th century BC, the authority of the New Kingdom dynasties had diminished, allowing divided rule in Egypt, and ending Egyptian control of Kush. With the withdrawal of the Egyptians, there ceased to be any written record or information from Kush about the region's activities over the next three hundred years. In the early eighth century BC, however, Kush emerged as an independent kingdom ruled from Napata by an aggressive line of monarchs who slowly extended their influence into Egypt. Around 750 BC, a Kushite king called Kashta

Kashta was an 8th century BC king of the Kushite Dynasty in ancient Nubia and the successor of Alara. His nomen ''k3š-t3'' (transcribed as Kashta, possibly pronounced /kuʔʃi-taʔ/) "of the land of Kush" is often translated directly as "The K ...

conquered Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient E ...

and became ruler of Thebes until approximately 740 BC. His successor, Piye, subdued the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

and conquered Egypt, thus initiating the Twenty-fifth Dynasty

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXV, alternatively 25th Dynasty or Dynasty 25), also known as the Nubian Dynasty, the Kushite Empire, the Black Pharaohs, or the Napatans, after their capital Napata, was the last dynasty of t ...

. Piye founded a line of kings who ruled Kush and Thebes for about a hundred years. The dynasty's interference with Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

's sphere of influence in the Near East caused a confrontation between Egypt and the powerful Assyrian state, which controlled a vast empire comprising much of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

and the Eastern Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

from their homeland in Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the region has been ...

.

Taharqa (688–663 BC), the last Kushite pharaoh, was defeated and driven out of the Near East by Sennacherib of Assyria. Sennacherib's successor Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of hi ...

went further, launching a full-scale invasion of Egypt in 674 BC, defeating Taharqa and quickly conquering the land. Taharqa fled back to Nubia, and native Egyptian princes were installed by the Assyrians as vassals of Esarhaddon. However, Taharqa was able to return some years later and wrest back control of a part of Egypt as far as Thebes from the Egyptian vassal princes of Assyria. Esarhaddon died in his capital Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ba ...

while preparing to return to Egypt and once more eject the Kushites.

Esarhaddon's successor Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Inheriting the throne a ...

sent a general with a small army which again defeated and ejected Taharqa from Egypt. Taharqa died in Nubia two years later. His successor, Tantamani

Tantamani ( egy, tnwt-jmn, Neo-Assyrian: , grc, Τεμένθης ), also known as Tanutamun or Tanwetamani (d. 653 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan, and the last pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. His p ...

, attempted to regain Egypt. He successfully defeated Necho I, the puppet ruler installed by Ashurbanipal, taking Thebes in the process. The Assyrians then sent a powerful army southwards. Tantamani

Tantamani ( egy, tnwt-jmn, Neo-Assyrian: , grc, Τεμένθης ), also known as Tanutamun or Tanwetamani (d. 653 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan, and the last pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. His p ...

was heavily routed, and the Assyrian army sacked Thebes to such an extent it never truly recovered. A native ruler, Psamtik I was placed on the throne, as a vassal of Ashurbanipal, thus ending the Kushite/Nubian Empire.

Meroë

Egypt's succeeding dynasty failed to reassert full control over Kush. Around 590 BC, however, an Egyptian army sacked Napata, compelling the Kushite court to move to a more secure location further south at Meroë near the Sixth Cataract. For several centuries thereafter, the Meroitic kingdom developed independently of Egyptian influence and domination, which passed successively underIran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

ian, Greek, and, finally, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

domination. During the height of its power in the second and third centuries BC, Meroë extended over a region from the Third Cataract in the north to Soba

Soba ( or , "buckwheat") is a thin Japanese noodle made from buckwheat. The noodles are served either chilled with a dipping sauce, or hot in a noodle soup. The variety ''Nagano soba'' includes wheat flour.

In Japan, soba noodles can be found ...

, near present-day Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

, in the south. An Egyptian-influenced pharaonic tradition persisted among a line of rulers at Meroë, who raised stelae to record the achievements of their reigns and erected Nubian pyramids

The Nubian pyramids were built by the rulers of the ancient Kushite kingdoms. The area of the Nile valley known as Nubia, which lies within the north of present-day Sudan, was the site of three Kushite kingdoms during antiquity. The capital of t ...

to contain their tombs. These objects and the ruins of palaces, temples, and baths at Meroë attest to a centralized political system that employed artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art ...

s' skills and commanded the labour of a large work force. A well-managed irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been devel ...

system allowed the area to support a higher population density than was possible during later periods. By the first century BC, the use of Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

gave way to a Meroitic alphabet

The Meroitic script consists of two alphasyllabic scripts developed to write the Meroitic language at the beginning of the Meroitic Period (3rd century BC) of the Kingdom of Kush. The two scripts are Meroitic Cursive, derived from Demotic Eg ...

adapted for the Nubian-related language spoken by the region's people.

Meroë's succession system was not necessarily hereditary; the matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

royal family member deemed most worthy often became king. The kandake

Kandake, kadake or kentake ( Meroitic: 𐦲𐦷𐦲𐦡 ''kdke''),Kirsty

Rowan"Revising the Sound Value of Meroitic D: A Phonological Approach,"''Beitrage zur Sudanforschung'' 10 (2009). often Latinised as Candace ( grc, Κανδάκη, ''Kandak� ...

or queen mother's role in the selection process was crucial to a smooth succession. The crown appears to have passed from brother to brother (or sister) and only when no siblings remained from father to son.

Although Napata remained Meroë's religious centre, northern Kush eventually fell into disorder as it came under pressure from the Blemmyes

The Blemmyes ( grc, Βλέμμυες, Latin: ''Blemmyae'') were an Eastern Desert people who appeared in written sources from the 7th century BC until the 8th century AD.. By the late 4th century, they had occupied Lower Nubia and established a ...

, predatory nomads from east of the Nile. However, the Nile continued to give the region access to the Mediterranean world. Additionally, Meroë maintained contact with Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

n traders along the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

coast and incorporated Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

n cultural influences into its daily life. Inconclusive evidence suggests that metallurgical technology may have been transmitted westward across the savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland- grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground ...

belt to West Africa from Meroë's iron smelteries.

Relations between Meroë and Egypt were not always peaceful. As a response to Meroë's incursions into Upper Egypt, a Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval contin ...

moved south and razed Napata in 23 BC. The Roman commander quickly abandoned the area, however, deeming it too poor to warrant colonization.

In the second century AD, the Nobatia occupied the Nile's west bank in northern Kush. They are believed to have been one of several well-armed bands of horse- and camel-borne warriors who sold their skills to Meroë for protection; eventually they intermarried and established themselves among the Meroitic people as a military aristocracy. Until nearly the fifth century, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

subsidized the Nobatia and used Meroë as a buffer between Egypt and the Blemmyes.

Meanwhile, the old Meroitic kingdom contracted because of the expansion of the powerful Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in w ...

to the east. By 350, King Ezana of Axum

Ezana ( gez, ዔዛና ''‘Ezana'', unvocalized ዐዘነ ''‘zn''; also spelled Aezana or Aizan) was ruler of the Kingdom of Axum, an ancient kingdom located in what is now Eritrea and Ethiopia. (320s – c. 360 AD). He himself employed the ...

had captured and destroyed the capital of Meroë, ending the kingdom's independent existence and conquering its territory.

Medieval Nubia (c. 350–1500)

On the turn of the fifth century, the

On the turn of the fifth century, the Blemmyes

The Blemmyes ( grc, Βλέμμυες, Latin: ''Blemmyae'') were an Eastern Desert people who appeared in written sources from the 7th century BC until the 8th century AD.. By the late 4th century, they had occupied Lower Nubia and established a ...

established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, probably centered around Talmis (Kalabsha

New Kalabsha is a promontory located near Aswan in Egypt.

Created during the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, it houses several important temples, structures, and other remains that have been relocated here from the site ...

), but before 450 they were already driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians. The latter eventually founded a kingdom on their own, Nobatia. By the 6th century there were in total three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, which had its capital at Pachoras ( Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria

Makuria (Old Nubian: , ''Dotawo''; gr, Μακουρία, Makouria; ar, المقرة, al-Muqurra) was a Nubians, Nubian monarchy, kingdom located in what is today Northern Sudan and Southern Egypt. Makuria originally covered the area along the N ...

centred at Tungul ( Old Dongola), about south of modern Dongola; and Alodia

Alodia, also known as Alwa ( grc-gre, Aρουα, ''Aroua''; ar, علوة, ''ʿAlwa''), was a medieval kingdom in what is now central and southern Sudan. Its capital was the city of Soba, located near modern-day Khartoum at the confluence of t ...

, in the heartland of the old Kushitic kingdom, which had its capital at Soba

Soba ( or , "buckwheat") is a thin Japanese noodle made from buckwheat. The noodles are served either chilled with a dipping sauce, or hot in a noodle soup. The variety ''Nagano soba'' includes wheat flour.

In Japan, soba noodles can be found ...

(now a suburb of modern-day Khartoum). Still in the sixth century they converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

. In the seventh century, probably at some point between 628 and 642, Nobatia was incorporated into Makuria.

Between 639 and 641 the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

of the Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate ( ar, اَلْخِلَافَةُ ٱلرَّاشِدَةُ, al-Khilāfah ar-Rāšidah) was the first caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was ruled by the first four successive caliphs of Muhammad after his ...

conquered Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Egypt. In 641 or 642 and again in 652 they invaded Nubia but were repelled, making the Nubians one of the few who managed to defeat the Arabs during the Islamic expansion

The spread of Islam spans about 1,400 years. Muslim conquests following Muhammad's death led to the creation of the caliphates, occupying a vast geographical area; conversion to Islam was boosted by Arab Muslim forces conquering vast territories ...

. Afterwards the Makurian king and the Arabs agreed on a unique non-aggression pact that also included an annual exchange of gifts, thus acknowledging Makuria's independence. While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia they began to settle east of the Nile, where they eventually founded several port towns and intermarried with the local Beja.

From the mid 8th-mid 11th century Christian Nubia went through its

From the mid 8th-mid 11th century Christian Nubia went through its Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

, when its political power and cultural development peaked. In 747 Makuria invaded Egypt, which at this time belonged to the declining Umayyads, and it did so again in the early 960s, when it pushed as far north as Akhmim

Akhmim ( ar, أخميم, ; Akhmimic , ; Sahidic/Bohairic cop, ) is a city in the Sohag Governorate of Upper Egypt. Referred to by the ancient Greeks as Khemmis or Chemmis ( grc, Χέμμις) and Panopolis ( grc, Πανὸς πόλις and Π ...

. Makuria maintained close dynastic ties with Alodia, perhaps resulting in the temporary unification of the two kingdoms into one state. The culture of the Medieval Nubians has been described as "''Afro-Byzantine''", with the significance of the "African" component increasing over time. Increasing Arab influence has also been noted. The state organization was extremely centralized, being based on the Byzantine bureaucracy of the 6th and 7th centuries. Arts flourished in the form of pottery paintings and especially wall paintings. The Nubians developed an own alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin, basing it on the Coptic alphabet

The Coptic alphabet is the script used for writing the Coptic language. The repertoire of glyphs is based on the Greek alphabet augmented by letters borrowed from the Egyptian Demotic and is the first alphabetic script used for the Egyptian ...

, while also utilizing Greek, Coptic and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. Women enjoyed high social status: they had access to education, could own, buy and sell land and often used their wealth to endow churches and church paintings. Even the royal succession was matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

, with the son of the king's sister being the rightful heir.

Since the late 11th/12th century, Makuria's capital Dongola was in decline, and Alodia's capital declined in the 12th century as well. In the 14th (the earliest recorded migration from Egypt to the Sudanese Nile Valley dates to 1324) and 15th century Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

tribes overran most of Sudan, migrating to the Butana

The Butana (Arabic: البطانة, ''Buṭāna''), historically called the Island of Meroë, is the region between the Atbara and the Nile in the Sudan. South of Khartoum it is bordered by the Blue Nile and in the east by Lake Tana in Ethiopia. ...

, the Gezira, Kordofan and Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju ...

. In 1365 a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda

Gebel Adda (also Jebel Adda) was a mountain and archaeological site on the right bank of the Nubian Nile in what is now southern Egypt. The settlement on its crest was continuously inhabited from the late Meroitic period (2nd century AD–4th cent ...

in Lower Nubia, while Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. Afterwards Makuria continued to exist only as a petty kingdom.

The last known Makurian king was Joel, who is attested for the years 1463 and 1484 and under whom Makuria probably witnessed a brief renaissance. After his death the kingdom probably collapsed.

To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either the Arabs, commanded by tribal leader Abdallah Jamma, or the Funj, an African people originating from the south. Datings range from the 9th century after the Hijra ( 1396–1494), the late 15th century, 1504 to 1509. An Alodian rump state might have survived in the form of the kingdom of Fazughli, lasting until 1685.

Islamic kingdoms (c. 1500–1821)

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the kingdom of Sennar

The Funj Sultanate, also known as Funjistan, Sultanate of Sennar (after its capital Sennar) or Blue Sultanate due to the traditional Sudanese convention of referring to black people as blue () was a monarchy in what is now Sudan, northwestern E ...

, in which Abdallah Jamma's realm was incorporated. By 1523, when Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

traveller David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already extended as far north as Dongola. Meanwhile, Islam began to be preached on the Nile by Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

holymen who settled there in the 15th and 16th centuries and by David Reubeni's visit king Amara Dunqas, previously a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim. However, the Funj would retain un-Islamic customs like the divine kingship or the consummation of alcohol until the 18th century. Sudanese folk Islam preserved many rituals stemming from Christian traditions until the recent past.

Soon the Funj came in conflict with the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, who had occupied Suakin around 1526 and eventually pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area in 1583/1584. A subsequent Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola was repelled by the Funj in 1585. Afterwards, Hannik, located just south of the third cataract, would mark the border between the two states. The aftermath of the Ottoman invasion saw the attempted usurpation of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. While the Funj eventually killed him in 1611/12, his successors, the Abdallab, were granted the authority to govern everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Niles with considerable autonomy.

During the 17th century the Funj state reached its widest extend, but in the following century it began to decline. A coup in 1718 brought a dynastic change, while another one in 1761-1762 resulted in the Hamaj regency The Hamaj Regency ( ar, وصاية ٱلهمج ) was a political order in the region of modern-day central Sudan from 1762 to 1821. During this period the ruling family of the Funj Sultanate of Sennar continued to reign, while actual power was exerc ...

, where the Hamaj (a people from the Ethiopian borderlands) effectively ruled while the Funj sultans were their mere puppets. Shortly afterwards the sultanate began to fragment; by the early 19th century it was essentially restricted to the Gezira.

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the Arabization

Arabization or Arabisation ( ar, تعريب, ') describes both the process of growing Arab influence on non-Arab populations, causing a language shift by the latter's gradual adoption of the Arabic language and incorporation of Arab culture, aft ...

of the state. In order to legitimize their rule over their Arab subjects the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descend. North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians would adopt the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin. Until the 19th century Arabic had succeeded in becoming the dominant language of central riverine Sudan and most of Kordofan.

West of the Nile, in Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju ...

, the Islamic period saw at first the rise of the Tunjur kingdom

The Tunjur kingdom was a Sahelian precolonial kingdom in Africa between the 15th and early 17th centuries.

Establishment

Local chronicles claim that the founder of the Tunjur dynasty became a "king in the island of Sennar". Origins of the Tunjur ...

, which replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 15th century and extended as far west as Wadai. The Tunjur people

__NOTOC__

The Tunjur (or Tungur) people are a Sunni Muslim ethnic group living in eastern Chad and western Sudan. In the 21st century, their number has been estimated at 175.000 people.

History

Based on linguistic and archaeological evidence, th ...

were probably Arabized Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

and, their ruling elite at least, Muslims. In the 17th century the Tunjur were driven from power by the Fur Keira sultanate. The Keira state, nominally Muslim since the reign of Sulayman Solong (r. 1660–1680), was initially a small kingdom in northern Jebel Marra, but expanded west- and northwards in the early 18th century and eastwards under the rule of Muhammad Tayrab

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

(r. 1751–1786), peaking in the conquest of Kordofan in 1785. The apogee of this empire, now roughly the size of present-day Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, would last until 1821.

19th century

Egyptian Conquest

From 1805, Egypt underwent a period of rapid modernisation under Muhammad Ali Pasha, who declared himselfKhedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"K ...

in defiance of his nominal suzerain, the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

. Within a matter of decades, Muhammad Ali transformed Egypt from a neglected Ottoman province to being a virtually independent state. Replicating the approach of his Mamluk predecessors in the medieval Sultanate of Egypt, Muhammad Ali sought to expand Egypt's frontiers southwards into Sudan, both as a means of guaranteeing Egypt's security, and to gain access to Sudan's natural resources. Between 1820–21, Egyptian forces under the command of Muhammad Ali's son conquered and unified the northern portion of the Sudan. Owing to Egypt's continuing de jure fealty to the Ottoman Sultan, the Egyptian administration was known as the ''Turkiyah

Turkish Sudan (), also known as Turkiyya ( ar, التركية, ''at-Turkiyyah''), describes the rule of the Eyalet and later Khedivate of Egypt over what is now Sudan and South Sudan. It lasted from 1820, when Muhammad Ali Pasha started his ...

.'' Historically, the pestilential swamps of the Sudd

The Sudd (' or ', Dinka: Toc) is a vast swamp in South Sudan, formed by the White Nile's '' Baḥr al-Jabal'' section. The Arabic word ' is derived from ' (), meaning "barrier" or "obstruction". The term "the sudd" has come to refer to any lar ...

discouraged expansion into the deeper south of the country. Although Egypt claimed all of present day Sudan during most of the 19th century, and established a province Equatoria

Equatoria is a region of southern South Sudan, along the upper reaches of the White Nile. Originally a province of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, it also contained most of northern parts of present-day Uganda, including Lake Albert and West Nile. It ...

in southern Sudan to further this aim, it was unable to establish effective control over all of the area. In the later years of the Turkiyah, British missionaries travelled from modern-day Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

into the Sudan to convert the local tribes to Christianity.

Mahdism and condominium

In 1881, a religious leader namedMuhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad ( ar, محمد أحمد ابن عبد الله; 12 August 1844 – 22 June 1885) was a Nubian Sufi religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, as a youth, studied Sunni Islam. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi, ...

proclaimed himself the Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad w ...

("guided one") and began a war to unify the tribes in western and central Sudan. His followers took the name " Ansars" ("followers") which they continue to use today, in association with the single largest political grouping, the Umma Party (once led by a descendant of the Mahdi, Sadiq al Mahdi). Taking advantage of conditions resulting from Ottoman-Egyptian exploitation and maladministration, the Mahdi led a nationalist revolt culminating in the fall of Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

on 26 January 1885. The interim governor-general of the Sudan, the British Major-General Charles George Gordon, and many of the fifty thousand inhabitants of Khartoum were massacred.

The Mahdi died in June 1885. He was followed by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, known as the Khalifa

Khalifa or Khalifah (Arabic: خليفة) is a name or title which means "successor", "ruler" or "leader". It most commonly refers to the leader of a Caliphate, but is also used as a title among various Islamic religious groups and others. Khalif ...

, who began an expansion of Sudan's area into Ethiopia. Following his victories in eastern Ethiopia, he sent an army to invade Egypt, where it was defeated by the British at Toshky. The British become aware of the weakness of the Sudan.

An Anglo-Egyptian force under Lord Kitchener in 1898 was sent to Sudan. Sudan was proclaimed a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

in 1899 under British-Egyptian administration. The Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

of the Sudan, for example, was appointed by "Khedival Decree", rather than simply by the British Crown, but while maintaining the appearance of joint administration, the British Empire formulated policies, and supplied most of the top administrators.

British control (1896–1955)

Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

. An 1896 agreement between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and Belgium saw the enclave turned over to the British after the death of King Leopold II in December 1909.

At the same time the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

claimed several areas: Bahr el Ghazal, and the Western Upper Nile up to Fashoda. By 1896 they had a firm administrative hold on these areas and they planned on annexing them to French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now B ...

. An international conflict known as the Fashoda incident developed between France and the United Kingdom over these areas. In 1899, France agreed to cede the area to the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

.

From 1898, the United Kingdom and Egypt administered all of present-day Sudan as the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, but northern and southern Sudan were administered as separate province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

s of the condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

. In the very early 1920s, the British passed the Closed Districts Ordinances which stipulated that passports were required for travel between the two zones, and permits were required to conduct business from one zone into the other, and totally separate administrations prevailed.

In the south, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, Dinka, Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Ital ...

, Nuer, Latuko, Shilluk, Azande and Pari (Lafon) were official languages, while in the north, Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and English were used as official languages. Islam was discouraged by the British in the south, where Christian missionaries were permitted to work. Condominium governors of south Sudan attended colonial conferences in East Africa, not in Khartoum, and the British hoped to add south Sudan to their East African colonies.

Most of the British focus was on developing the economy and infrastructure of the north. Southern political arrangements were left largely as they had been prior to the arrival of the British. Until the 1920s, the British had limited authority in the south.

In order to establish their authority in the north, the British promoted the power of Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani, head of the Khatmiyya

The Khatmiyya is a Sufi order or tariqa founded by Sayyid Mohammed Uthman al-Mirghani al-Khatim.

The Khatmiyya is the largest Sufi order in Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. It also has followers in Egypt, Chad, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Uganda, Yemen ...

sect and Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, head of the Ansar sect. The Ansar sect essentially became the Umma party, and Khatmiyya became the Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. Currently led by J ...

.

In 1943, the British began preparing the north for self-government, establishing a North Sudan Advisory Council to advise on the governance of the six North Sudanese provinces: Khartoum, Kordofan, Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju ...

, and Eastern, Northern, and Blue Nile provinces. Then, in 1946, the British administration reversed its policy and decided to integrate north and south Sudan under one government. The South Sudanese authorities were informed at the Juba Conference of 1947 that they would in future be governed by a common administrative authority with the north. From 1948, 13 delegates, nominated by the British authorities, represented the south on the Sudan Legislative Assembly.

Many southerners felt betrayed by the British, because they were largely excluded from the new government. The language of the new government was Arabic, but the bureaucrats and politicians from southern Sudan had, for the most part, been trained in English. Of the eight hundred new governmental positions vacated by the British in 1953, only four were given to southerners.

Also, the political structure in the south was not as organized in the north, so political groupings and parties from the south were not represented at the various conferences and talks that established the modern state of Sudan. As a result, many southerners did not consider Sudan to be a legitimate state.

Independent Sudan (1956 to present)

Independence and the First Civil War

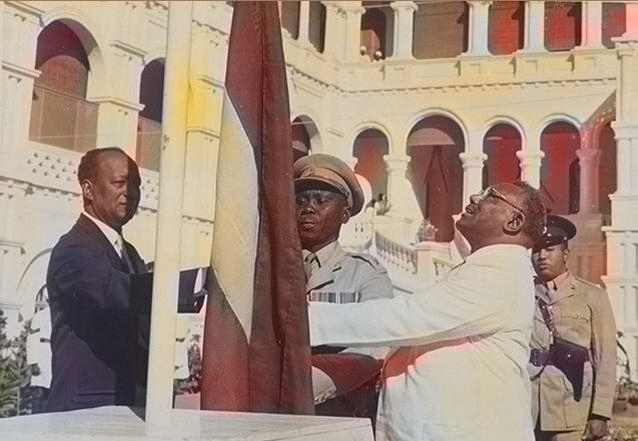

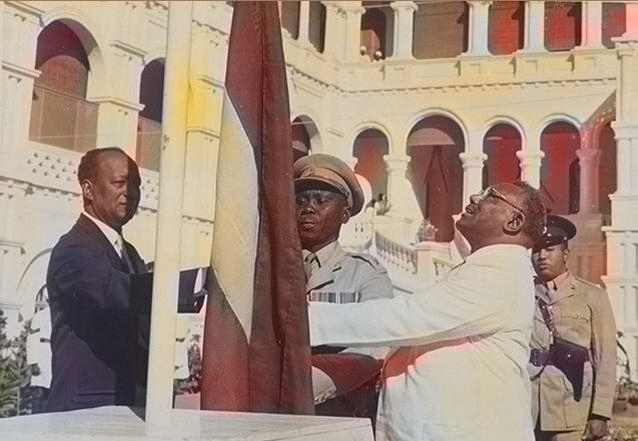

In February 1953, the

In February 1953, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and Egypt concluded an agreement providing for Sudanese self-government and self-determination. The transitional period toward independence began with the inauguration of the first parliament in 1954. On 18 August 1955 a revolt in the army in Torit Southern Sudan broke out, which although quickly suppressed, led to a low level guerrilla insurgency by former Southern rebels, and marked the beginning of the First Sudanese Civil War. On 15 December 1955 the Premier of Sudan Ismail al-Azhari

Ismail al-Azhari (October 20, 1900 – August 26, 1969) ( ar, إسماعيل الأزهري) was a Sudanese nationalist and political figure. He served as the first Prime Minister of Sudan between 1954 and 1956, and as President of Sudan from ...

announced that Sudan would unilaterally declare independence in four days time. On 19 December 1955 the Sudanese parliament, unilaterally and unanimously, declared Sudan's independence. The British and Egyptian governments recognized the independence of Sudan on 1 January 1956. The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

was among the first foreign powers to recognize the new state. However, the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

-led Khartoum government reneged on promises to southerners to create a federal system, which led to a mutiny by southern army officers that sparked seventeen years of civil war (1955–1972). In the early period of the war, hundreds of northern bureaucrats, teachers, and other officials, serving in the south were massacred.

The National Unionist Party (NUP), under Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari

Ismail al-Azhari (October 20, 1900 – August 26, 1969) ( ar, إسماعيل الأزهري) was a Sudanese nationalist and political figure. He served as the first Prime Minister of Sudan between 1954 and 1956, and as President of Sudan from ...

, dominated the first cabinet, which was soon replaced by a coalition of conservative political forces. In 1958, following a period of economic difficulties and political manoeuvring that paralysed public administration, Chief of Staff Major General Ibrahim Abboud overthrew the parliamentary regime in a bloodless coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

.

Gen. Abboud did not carry out his promises to return Sudan to civilian government, however, and popular resentment against army rule led to a wave of riots and strikes in late October 1964 that forced the military to relinquish power.

The Abboud regime was followed by a provisional government until parliamentary elections in April 1965 led to a coalition government of the Umma and National Unionist Parties under Prime Minister Muhammad Ahmad Mahjoub. Between 1966 and 1969, Sudan had a series of governments that proved unable either to agree on a permanent constitution or to cope with problems of factionalism, economic stagnation, and ethnic dissidence. The succession of early post-independence governments were dominated by Arab Muslims

Arab Muslims ( ar, العرب المسلمون) are adherents of Islam who identify linguistically, culturally, and genealogically as Arabs. Arab Muslims greatly outnumber other ethnoreligious groups in the Middle East and North Africa. Arab M ...

who viewed Sudan as a Muslim Arab state. Indeed, the Umma/NUP proposed 1968 constitution was arguably Sudan's first Islamic-oriented constitution.

The Nimeiry Era

Dissatisfaction culminated in a second coup d'état on May 25, 1969. The coup leader, Col. Gaafar Nimeiry, became prime minister, and the new regime abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties. Disputes betweenMarxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

and non-Marxist elements within the ruling military coalition resulted in a briefly successful coup in July 1971, led by the Sudanese Communist Party. Several days later, anti-communist military elements restored Nimeiry to power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a cessation of the north–south civil war and a degree of self-rule. This led to ten years hiatus in the civil war.

Until the early 1970s, Sudan's agricultural output was mostly dedicated to internal consumption. In 1972, the Sudanese government became more pro-Western, and made plans to export food and cash crop

A cash crop or profit crop is an agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") in subsist ...

s. However, commodity prices declined throughout the 1970s causing economic problems for Sudan. At the same time, debt servicing costs, from the money spent mechanizing agriculture, rose. In 1978, the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glo ...

(IMF) negotiated a Structural Adjustment Program with the government. This further promoted the mechanized export agriculture sector. This caused great economic problems for the pastoralists of Sudan (See Nuba Peoples).

In 1976, the Ansars mounted a bloody but unsuccessful coup attempt. In July 1977, President Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, opening the way for reconciliation. Hundreds of political prisoners were released, and in August a general amnesty was announced for all opponents of Nimeiry's government.

Arms suppliers

Sudan relied on a variety of countries for its arms supplies. Since independence the army had been trained and supplied by the British, but relations were cut off after the Arab-IsraelSix-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

in 1967. At this time relations with the US and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

were also cut off. From 1968 to 1971, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and eastern bloc nations sold large numbers of weapons and provided technical assistance and training to Sudan. At this time the army grew from a strength of 18,000 to roughly 60,000 men. Large numbers of tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

s, aircraft, and artillery were acquired at this time, and they dominated the army until the late 1980s. Relations cooled between the two sides after the coup in 1971, and the Khartoum government sought to diversify its suppliers. Egypt was the most important military partner in the 1970s, providing missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket ...

s, personnel carriers, and other military hardware.

Western countries began supplying Sudan again in the mid 1970s. The United States began selling Sudan a great deal of equipment around 1976. Military sales peaked in 1982 at US$101 million. The alliance with the United States was strengthened under the administration of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

. American aid increased from $5 million in 1979 to $200 million in 1983 and then to $254 million in 1985, mainly for military programs. Sudan thus became the second largest recipient of US aid to Africa (after Egypt). The construction of four air bases to house Rapid Deployment Force units and a powerful listening station for the CIA near Port Sudan was decided.

Second Civil War

In 1983, the civil war in the South was reignited following the government's Islamification policy which would have instituted Islamic law, among other things. After several years of fighting, the government compromised with southern groups. In 1984 and 1985; after a period of drought, several million people were threatened by famine, particularly in western Sudan. The regime is trying to hide the situation internationally. In March 1985, the announcement of the increase in the prices of basic necessities, at the request of the IMF with which the regime was negotiating, triggered the first demonstrations. On April 2, eight unions called for mobilization and a "general political strike until the abolition of the current regime". On the 3rd, massive demonstrations shook Khartoum, but also the country's main cities; the strike paralysed institutions and the economy. On April 6, 1985, a group of military officers, led by Lieutenant General Abd ar Rahman Siwar adh Dhahab, overthrew Nimeiri, who took refuge in Egypt. Three days later, Dhahab authorized the creation of a fifteen-man Transitional Military Council (TMC) to rule Sudan. In June 1986, Sadiq al Mahdi formed a coalition government with Umma Party, theDemocratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. Currently led by J ...

(DUP), the National Islamic Front

The National Islamic Front ( ar, الجبهة الإسلامية القومية; transliterated: ''al-Jabhah al-Islamiyah al-Qawmiyah'') was an Islamist political organization founded in 1976 and led by Dr. Hassan al-Turabi that influenced th ...