History of Newfoundland and Labrador on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The province of

The first European contact with North America was that of the medieval Norse settlers arriving via Greenland. For several years after AD 1000 they lived in a village on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula at

The first European contact with North America was that of the medieval Norse settlers arriving via Greenland. For several years after AD 1000 they lived in a village on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula at

This was changed back after some agitation in 1848 to two separate chambers. After this, a movement for

This was changed back after some agitation in 1848 to two separate chambers. After this, a movement for

In the 1850s newly formed local banks became a source of credit, replacing the haphazard system of credit from local merchants. Prosperity brought immigration, especially Catholics from Ireland who soon composed 40 per cent of the residents. Small-scale seasonal farming became widespread, and mines began to exploit abundant reserves of lead, copper, zinc, iron, and coal. Railways were opened in the 1880s, with the link from St. John's to Port aux Basques open in 1898. In 1895 Newfoundland again rejected the possibility of joining Canada.

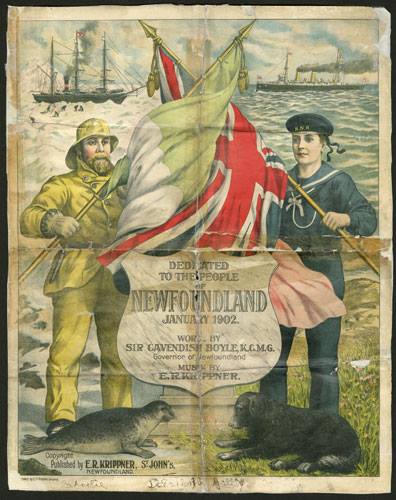

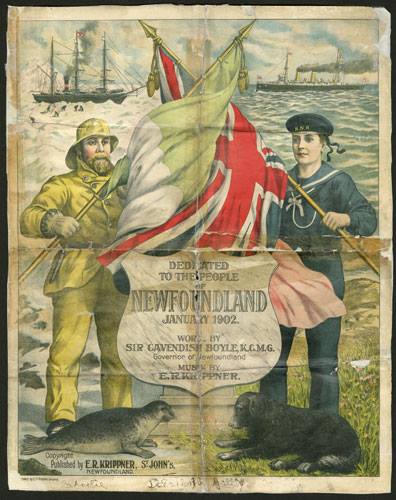

Seal hunting off the coast of Labrador, for the fur, became a small specialty in the late 18th century. It began with nets and traps, which gave way to the versatility of sail-driven ships around 1800. Sailing ships gave way to the greater range, power, and reliability of steam-driven vessels after 1863.

In the 1850s newly formed local banks became a source of credit, replacing the haphazard system of credit from local merchants. Prosperity brought immigration, especially Catholics from Ireland who soon composed 40 per cent of the residents. Small-scale seasonal farming became widespread, and mines began to exploit abundant reserves of lead, copper, zinc, iron, and coal. Railways were opened in the 1880s, with the link from St. John's to Port aux Basques open in 1898. In 1895 Newfoundland again rejected the possibility of joining Canada.

Seal hunting off the coast of Labrador, for the fur, became a small specialty in the late 18th century. It began with nets and traps, which gave way to the versatility of sail-driven ships around 1800. Sailing ships gave way to the greater range, power, and reliability of steam-driven vessels after 1863.

As part of the Anglo-French

As part of the Anglo-French

During the great

During the great

In 1940

In 1940

Canada issued an invitation to join it on generous financial terms. Smallwood was elected to the convention where he became the leading proponent of confederation with Canada, insisting, "Today we are more disposed to feel that our very manhood, our very creation by God, entitles us to standards of life no lower than our brothers on the mainland." Displaying a mastery of propaganda technique, courage and ruthlessness, he succeeded in having the Canada option on the referendum. His main opponents were

Canada issued an invitation to join it on generous financial terms. Smallwood was elected to the convention where he became the leading proponent of confederation with Canada, insisting, "Today we are more disposed to feel that our very manhood, our very creation by God, entitles us to standards of life no lower than our brothers on the mainland." Displaying a mastery of propaganda technique, courage and ruthlessness, he succeeded in having the Canada option on the referendum. His main opponents were

Considerable attention was paid to the infrastructure for Labrador, especially building railway systems to transport the minerals and raw materials from Labrador to Quebec, and an electricity grid. In the 1960s, the province developed the Churchill Falls hydro-electric facility in order to sell electricity to the United States. An agreement with Quebec was required to secure permission to transport the electricity across Quebec territory. Quebec drove a hard bargain with Newfoundland, resulting in a 75-year deal that Newfoundlanders now believe to be unfair to the province because of the low and unchangeable rate that it receives for the electricity. In addition to energy production, iron mining did not begin in Labrador until the 1950s. By 1990, the Quebec-Labrador area had become an important supplier of iron ore to the United States.

In the late 1980s, the federal government, along with its

Considerable attention was paid to the infrastructure for Labrador, especially building railway systems to transport the minerals and raw materials from Labrador to Quebec, and an electricity grid. In the 1960s, the province developed the Churchill Falls hydro-electric facility in order to sell electricity to the United States. An agreement with Quebec was required to secure permission to transport the electricity across Quebec territory. Quebec drove a hard bargain with Newfoundland, resulting in a 75-year deal that Newfoundlanders now believe to be unfair to the province because of the low and unchangeable rate that it receives for the electricity. In addition to energy production, iron mining did not begin in Labrador until the 1950s. By 1990, the Quebec-Labrador area had become an important supplier of iron ore to the United States.

In the late 1980s, the federal government, along with its

However, the situation changed in the 1990s as a result of the

However, the situation changed in the 1990s as a result of the

In October 2003, the Liberals lost the provincial election to the Progressive Conservative Party, led by Danny Williams. In 2004, Premier Williams has argued that Prime Minister

In October 2003, the Liberals lost the provincial election to the Progressive Conservative Party, led by Danny Williams. In 2004, Premier Williams has argued that Prime Minister

Nationalist sentiment in the 21st century has become a powerful force in Newfoundland politics and culture, layered on top of a traditional culture deeply embedded in the outports. Gregory (2004) sees it as a development of the late 20th century, for in the 1940s it was not strong enough to stop confederation with Canada, and the people in the cities adopted a

Nationalist sentiment in the 21st century has become a powerful force in Newfoundland politics and culture, layered on top of a traditional culture deeply embedded in the outports. Gregory (2004) sees it as a development of the late 20th century, for in the 1940s it was not strong enough to stop confederation with Canada, and the people in the cities adopted a

online

* Fay, C. R.; ''Life and Labour in Newfoundland'' University of Toronto Press, 1956 * Greene, John P. ''Between Damnation and Starvation: Priests and Merchants in Newfoundland Politics, 1745–1855.''McGill-Queen's U. Press, 2000. 340 pp. * Guy, Raymond W. ''Memory is a Fickle Jade: A Collection of Historical Essays about Newfoundland and Her People.'' St. John's, : Creative Book Publ., 1996. 202 pp. * Hale, David. "The Newfoundland Lesson," ''The International Economy.'' v17#3 (Summer 2003). pp 52+

online edition

* Handcock, W. Gordon. ''Newfoundland Origins and Patterns of Migration: A Statistical and Cartographic Summary.'' (St. John's: Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1977). * Handcock, W. Gordon. ''Soe Longe as There Comes Noe Women: Origins of English Settlement in Newfoundland.'' (Milton Ontario: Global Heritage Press, 2003). * Harris, Leslie. ''Newfoundland and Labrador: A Brief History'' (1968) * Hollett, Calvin. ''Shouting, Embracing, and Dancing with Ecstasy: The Growth of Methodism in Newfoundland, 1774–1874'' (2010) * Jackson, Lawrence. ''Newfoundland & Labrador'' Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd; (1999) ; * Kealey, Linda, ed. ''Pursuing Equality: Historical Perspectives on Women in Newfoundland and Labrador.'' St. John's: Institute of Social and Economic Research, 1993. 310 pp. * Gene Long, ''Suspended State: Newfoundland Before Canada'' Breakwater Books Ltd; ; (1999) * R. A. MacKay; ''Newfoundland; Economic, Diplomatic, and Strategic Studies'' Oxford University Press, (1946) * McCann, Phillip. ''Schooling in a Fishing Society: Education and Economic Conditions in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1836–1986.'' St. John's: Inst. of Social and Econ. Res., 1994. 277 pp. *Neary, Peter. . ''Newfoundland in the North Atlantic world, 1929–1949''. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996 * O'Flaherty, Patrick. ''Old Newfoundland: A History to 1843.'' St John's: Long Beach, 1999. 284 pp. * Pope, Peter E. ''Fish into Wine: The Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century.'' U. of North Carolina Press, 2004. 464 pp. * * Rowe, Frederick. ''History of Newfoundland and Labrador'' (1980). * Whitcomb, Dr. Ed. ''A Short History of Newfoundland and Labrador''. Ottawa. From Sea To Sea Enterprises, 2011. . 64 pp. * Wright, Miriam. ''A Fishery for Modern Times: The State and the Industrialization of the Newfoundland Fishery, 1934–1968.'' Oxford U. Press, 2001. 176 pp.

edition

* Moyles, Robert Gordon, ed. ''"Complaints is Many and Various, But the Odd Divil Likes It": Nineteenth Century Views of Newfoundland'' (1975). * Neary, Peter, and Patrick O'Flaherty, eds. ''By Great Waters: A Newfoundland and Labrador Anthology'' (1974) * O'Flaherty, Patrick ed. ''The Rock Observed: Literary Responses to Newfoundland and Its People'' (1979) * Rompkey, Ronald, ed. ''Terre-Neuve: Anthologie des Voyageurs Français, 1814–1914'' ewfoundland: anthology of French travelers, 1814–1914 Presse University de Rennes, 2004. 304 pp. * Smallwood, Joseph R. ''I Chose Canada: The Memoirs of the Honourable Joseph R. "Joey" Smallwood.'' (1973). 600 pp.

edition

* Joseph Hatton and Moses Harvey, ''Newfoundland: Its History and Present Condition'', (London, 1883

complete text online

* Millais, John Guille. '' The Newfoundland Guide Book, 1911: Including Labrador and St. Pierre'' (1911

online edition; also reprinted 2009

* D. W. Prowse, ''A History of Newfoundland'' (1895), current edition 2002, Boulder Publications, Portugal Cove, Newfoundland

text online

* Pedley, Charles. ''History of Newfoundland'', (London, 1863

complete text online

* Tocque, Philip. ''Newfoundland as it Was and Is'', (London, 1878

complete text online

* Kennedy, Arnold. ''Sport and Adventure in Newfoundland and West Indies'', (London, 1885

complete text online

* Moses Harvey, ''Newfoundland, England's Oldest Colony'', (London, 1897

complete text online

* J. P. Howley, ''Mineral Resources of Newfoundland'', (St. John's, 1909) * P. T. McGrath, ''Newfound in 1911'', (London, 1911) * ''Year Book and Almanac of Newfoundland'' edited by J.W. Withers *

1896 edition

*

1905 edition

*

1910 edition

*

1914 edition

*

1917 edition

*

1919 edition

*

other editions

with a large number of quotations

Government of Newfoundland and LabradorCentre for Newfoundland Studies

by scholar; containing biographies and primary sources, * Rollmann, Hans

"Religion, Society and Culture in Newfoundland and Labrador."

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Newfoundland And Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

covers the period from habitation by Archaic peoples thousands of years ago to the present day.

Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

were inhabited for millennia by different groups of Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. The first brief European contact with Newfoundland and Labrador came around 1000 AD when the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

briefly settled in L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows ( lit. Meadows Cove) is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland in the C ...

. In 1497, European explorers and fishermen from England, Portugal, Spain (mainly Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Ba ...

), France and Holland began exploration. Fishing expeditions came seasonally; the first small permanent settlements appeared around 1630. Catholic-Protestant religious tensions were high but mellowed after 1860. The British colony voted against joining Canada in 1869 and became an independent dominion in 1907. After the economy collapsed in the 1930s, responsible government was suspended in 1934, and Newfoundland was governed through the Commission of Government. Prosperity and self-confidence returned during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, and after the intense debate, the people voted to join Canada in 1948. Newfoundland was formally admitted into Canadian Confederation in 1949.

Poverty and emigration have remained significant themes in Newfoundland history, despite efforts to modernize since entering Confederation. Over the second half of the 20th century, the historic cultural and political tensions between British Protestants and Irish Catholics faded, and a new spirit of a unified Newfoundland identity has recently emerged through songs and popular culture. During the 1990s, the province was severely impacted by the sudden collapse of the Atlantic cod fishing industry. The 2000s brought an renewed interest in the oil sector, which helped to revitalize the economy of the province.

Early history

Human habitation in Newfoundland and Labrador can be traced back about 9000 years to the Maritime Archaic people. They were gradually displaced by people of theDorset Culture

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from to between and , that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset (now Kinngait) in ...

—Thule

Thule ( grc-gre, Θούλη, Thoúlē; la, Thūlē) is the most northerly location mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman literature and cartography. Modern interpretations have included Orkney, Shetland, northern Scotland, the island of Saar ...

and finally by the Innu

The Innu / Ilnu ("man", "person") or Innut / Innuat / Ilnuatsh ("people"), formerly called Montagnais from the French colonial period ( French for "mountain people", English pronunciation: ), are the Indigenous inhabitants of territory in the ...

and Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

in Labrador and the Beothuks on Newfoundland.

European exploration

The first European contact with North America was that of the medieval Norse settlers arriving via Greenland. For several years after AD 1000 they lived in a village on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula at

The first European contact with North America was that of the medieval Norse settlers arriving via Greenland. For several years after AD 1000 they lived in a village on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula at L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows ( lit. Meadows Cove) is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland in the C ...

. Remnants and artifacts of the occupation is present at L'Anse aux Meadows, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

. The island was inhabited by the Beothuks (known as the ''Skræling

''Skræling'' (Old Norse and Icelandic: ''skrælingi'', plural ''skrælingjar'') is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America (Canada and Greenland). In surviving sources, it is first applied to the ...

'' in Greenlandic Norse

Greenlandic Norse is an extinct North Germanic language that was spoken in the Norse settlements of Greenland until their demise in the late 15th century. The language is primarily attested by runic inscriptions found in Greenland. The limited ...

) and later by the Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the no ...

.

From the late 15th Century, European explorers like John Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal Nor ...

, João Fernandes Lavrador

João Fernandes Lavrador (1453-1501) () was a Portuguese explorer of the late 15th century. He was one of the first modern explorers of the Northeast coasts of North America, including the large Labrador peninsula, which was named after him b ...

, Gaspar Corte-Real

Gaspar Corte-Real (1450–1501) was a Portuguese explorer who, alongside his father João Vaz Corte-Real and brother Miguel, participated in various exploratory voyages sponsored by the Portuguese Crown. These voyages are said to have been some o ...

, Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French- Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of ...

and others began exploration.

European fishing expeditions

Fishing vessels with Basque, English, Portuguese, French, Dutch and Spanish crews started to make seasonal expeditions. Basque vessels had been fishing cod shoals off Newfoundland's coasts since the beginning of the 16th century, and their crews used the natural harbour at Placentia. French fishermen also began to use the area.Colony of Newfoundland

John Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 – 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal Nor ...

(1450–1499), commissioned by King Henry VII of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, landed on the North East coast of North America in 1497. The exact location of his landing is unknown but the 500th anniversary of his landing was commemorated in Bonavista. The 1497 voyage has generated much debate among historians, with various points in Newfoundland, and Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, most often identified as the likely landing place. Sir Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an English adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America ...

, provided with letters patent from Queen Elizabeth I, landed in St John's in August 1583, and formally took possession of the island.

17th and 18th centuries

From 1616, EnglishProprietary Governor

A proprietary colony was a type of English colony mostly in North America and in the Caribbean in the 17th century. In the British Empire, all land belonged to the monarch, and it was his/her prerogative to divide. Therefore, all colonial propert ...

s were also appointed, to establish colonial settlements on the island. John Guy was governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of the first settlement at Cuper's Cove

Cuper's Cove, on the southwest shore of Conception Bay on Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula was an early English settlement in the New World, and the third one after Harbour Grace, Newfoundland (1583) and Jamestown, Virginia (1607) to endure for lo ...

. Other settlements were Bristol's Hope, Renews, New Cambriol, South Falkland and Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in the ...

which became a province in 1623. The first governor given jurisdiction over all of Newfoundland was Sir David Kirke

Sir David Kirke ( – 1654), also spelt David Ker, was an adventurer, privateer and colonial governor. He is best known for his successful capture of Québec in 1629 during the Thirty Years' War and his subsequent governorship of lands in Ne ...

in 1638.

From the 1770s to the late 19th century, Moravian missionaries, Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

agents, and other pioneer settlers along central Labrador's coastline learned to adapt to its rocky terrain, brutal winters, and its thin soil and scant sunshine. To maintain good health, to avoid the monotony of dried, salted, and tinned foods, and to reduce reliance on expensive imported food, they created gardens and succeeded after much experimentation in growing hardy vegetables and even some fragile crops.

Fishing

Explorers soon realized that the waters around Newfoundland had the best fishing in the North Atlantic. By 1620, 300 fishing boats worked the Grand Bank, employing some 10,000 sailors; many were French or Basques from Spain. They dried and salted the cod on the coast and sold it to Spain and Portugal. Heavy investment by SirGeorge Calvert

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (; 1580 – 15 April 1632), was an English politician and colonial administrator. He achieved domestic political success as a member of parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I. He lost m ...

, 1st Baron Baltimore, in the 1620s in wharves, warehouses, and fishing stations failed to pay off. French raids hurt the business, and the weather was terrible, so he redirected his attention to his other colony in Maryland. After Calvert left small-scale entrepreneurs such as Sir David Kirke

Sir David Kirke ( – 1654), also spelt David Ker, was an adventurer, privateer and colonial governor. He is best known for his successful capture of Québec in 1629 during the Thirty Years' War and his subsequent governorship of lands in Ne ...

made good use of the facilities. Kirke became the first governor in 1639. A triangular trade with New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, the West Indies, and Europe gave Newfoundland an important economic role. By the 1670s there were 1700 permanent residents and another 4500 in the summer months.

Newfoundland cod formed one leg of a triangular trade that sent cod to Spain and the Mediterranean, and wine, fruit, olive oil, and cork to England. Dutch ships were especially active during the time between 1620–1660 in what was called the "sack trade." A ship of 250 tons could earn 14% profit on the Newfoundland to Spain leg, and about the same on goods it then took from Spain to England. The journey across the Atlantic was stormy and risky; the risk was spread mostly by selling shares.

Before 1700 the "admiral" system provided the government. The first captain arriving in a particular bay was in charge of allocating suitable shoreline sites for curing fish. The system faded away after 1700. Fishing-boat captains competed to arrive first from Europe in an attempt to become the admiral; soon merchants left crewmen behind at the prime shoreline locations to lay claim to the sites. This led to "bye-boat" fishing: local, small-boat crews fished certain areas in the summer, claimed a strip of land as their own, and sold their catches to the migratory fishermen. Bye-boat fishing thus became dominant, giving the island a semi-permanent population, and proved more profitable than migratory fishing.

The fishing admirals system ended in 1729 when the Royal Navy sent in its officers to govern during the fishing season.

International disputes

In 1655, France appointed a governor at ''Plaisance'', as Placentia was known in French, thus starting the French colonization of Newfoundland. In 1697, during the devastating Avalon Peninsula Campaign,Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

almost claimed the English settlements for New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

. However, the French failed to defend their conquest of the English portion of the island. The French colonization period lasted until the conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

in 1713. In the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

, France ceded its claims to Newfoundland to the British (as well as its claims to the shores of Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

). In addition, the French possessions in Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

were also yielded to Britain. Afterward, under the supervision of the last French governor, the French population of Plaisance moved to Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

), part of Acadia which remained then under French control.

In the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

(1713), France acknowledged British ownership of the island. However, in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

(1756–63), control of Newfoundland became a major source of conflict between Britain, France and Spain who all pressed for a share in the valuable fishery there. Britain's victories around the globe led William Pitt to insist that no other power might have access to Newfoundland. In 1762, a French force landed in Newfound and initially succeeded in occupying eastern portions of the island including the important port of St. John's. However, French ambitions of conquering the island ended in defeat at the Battle of Signal Hill. In 1796 a Franco-Spanish expedition succeeded in raiding the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador.

By the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), French fishermen were given the right to land and cure fish on the "French Shore

The French Shore (French: ''Côte française de Terre-Neuve''), also called The Treaty Shore, resulted from the 1713 ratifications of the Treaty of Utrecht. The provisions of the treaty allowed the French to fish in season along the north coast of ...

" on the western coast. They had a permanent base on nearby St. Pierre and Miquelon islands; the French gave up their rights in 1904. In 1783, the British signed the Treaty of Paris with the United States that gave American fishermen similar rights along the coast. These rights were reaffirmed by treaties in 1818, 1854 and 1871 and confirmed by arbitration in 1910.

During the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

, a combined Franco-Spanish force conducted a series of maritime maneuvers and raids on Newfoundland in 1796.

19th century

Newfoundland received a colonial assembly in1832

Events

January–March

* January 6 – Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison founds the New-England Anti-Slavery Society.

* January 13 – The Christmas Rebellion of slaves is brought to an end in Jamaica, after the island's white plant ...

, which was and still is referred to as the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony adm ...

, after a fight led by reformers William Carson

Sir William Carson (baptised 4 June 1770 – 26 February 1843), often called "The Great Reformer", was a medical doctor and businessman in Newfoundland. Carson's primary contribution to Newfoundland was the application of modern agricultural ...

, Patrick Morris and John Kent. The establishment of a colonial assembly was partly due to Scottish physician William Carson

Sir William Carson (baptised 4 June 1770 – 26 February 1843), often called "The Great Reformer", was a medical doctor and businessman in Newfoundland. Carson's primary contribution to Newfoundland was the application of modern agricultural ...

(1770–1843), who came to the island in 1808. He called for the replacement of the system of arbitrary rule by naval commanders, seeking instead to have a resident governor and an elective legislature. Carson's systematic agitation helped win London's recognition of Newfoundland as a colony (1824) and the grant of an elective house (1832). Carson was the reform leader in the House of Assembly (1834–1843, speaker 1837–1841). He served on the Executive Council (1842–1843).

This was changed back after some agitation in 1848 to two separate chambers. After this, a movement for

This was changed back after some agitation in 1848 to two separate chambers. After this, a movement for responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

began. Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

obtained a "responsible" government in 1848 (whereby the assembly had the final word, not the royal governor), and Newfoundland followed in 1855. Self-government was now a reality. The Liberal Party, based on the Irish Catholic vote, alternated with the Conservatives, with its base among the merchant class and Protestants. With a prosperous population of 120,000, Newfoundlanders decided to pass in 1869 on joining the new confederation of Canada.

In 1861 the Protestant governor dismissed the Catholic Liberals from office and the ensuing election was marked by riot and disorder with both bishop Edward Feild

Edward Feild (7 June 1801 at Worcester, England – 8 June 1876 at Hamilton, Bermuda) was a university tutor, university examiner, Anglican clergyman, inspector of schools and second Bishop of Newfoundland.

Early years

Born in Worcester, E ...

of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and Catholic bishop Thomas Mullock taking partisan stances. The Protestants narrowly elected Hugh Hoyles

Sir Hugh Hoyles (October 17, 1814 – February 1, 1888) was a politician and lawyer who served as the third premier of the colony of Newfoundland. Hoyles was the first premier of Newfoundland to have been born in the colony, and served from 18 ...

as the Conservative Prime Minister. Hoyles suddenly reversed his long record of militant Protestant activism and worked to defuse tensions. He shared patronage and power with the Catholics; all jobs and patronage were split between the various religious bodies on a per capita basis. This 'denominational compromise' was further extended to education when all religious schools were put on the basis which the Catholics had enjoyed since the 1840s. Alone in North America Newfoundland had a state-funded system of denominational schools. The compromise worked and politics ceased to be about religion and became concerned with purely political and economic issues.

By the 1890s St John's was no longer regarded in England as akin to Belfast, and ''Blackwood's Magazine'' was using developments there as an argument for Home Rule for Ireland. Newfoundland rejected confederation with Canada in the 1869 general election. Sir Robert Bond

Sir Robert Bond (25 February 1857 – 16 March 1927) was the last Premier of Newfoundland Colony from 1900 to 1907 and the first prime minister of the Dominion of Newfoundland from 1907 to 1909 after the 1907 Imperial Conference conferred ...

(1857–1927) was a Newfoundland nationalist who insisted upon the colony's equality of status with Canada, and opposed joining the confederation. Bond promoted the completion of a railway across the island (started in 1881) because it would open access to valuable minerals and timber and reduce the almost total dependence on the cod fisheries. He advocated closer economic ties with the United States, and distrusted London for ignoring the island's viewpoint on the controversial issue of allowing French fisherman to process lobsters on the French Coast, and for blocking a trade deal with the U.S. Bond became Liberal Party leader in 1899 and premier in 1900.

Economy

In the 1850s newly formed local banks became a source of credit, replacing the haphazard system of credit from local merchants. Prosperity brought immigration, especially Catholics from Ireland who soon composed 40 per cent of the residents. Small-scale seasonal farming became widespread, and mines began to exploit abundant reserves of lead, copper, zinc, iron, and coal. Railways were opened in the 1880s, with the link from St. John's to Port aux Basques open in 1898. In 1895 Newfoundland again rejected the possibility of joining Canada.

Seal hunting off the coast of Labrador, for the fur, became a small specialty in the late 18th century. It began with nets and traps, which gave way to the versatility of sail-driven ships around 1800. Sailing ships gave way to the greater range, power, and reliability of steam-driven vessels after 1863.

In the 1850s newly formed local banks became a source of credit, replacing the haphazard system of credit from local merchants. Prosperity brought immigration, especially Catholics from Ireland who soon composed 40 per cent of the residents. Small-scale seasonal farming became widespread, and mines began to exploit abundant reserves of lead, copper, zinc, iron, and coal. Railways were opened in the 1880s, with the link from St. John's to Port aux Basques open in 1898. In 1895 Newfoundland again rejected the possibility of joining Canada.

Seal hunting off the coast of Labrador, for the fur, became a small specialty in the late 18th century. It began with nets and traps, which gave way to the versatility of sail-driven ships around 1800. Sailing ships gave way to the greater range, power, and reliability of steam-driven vessels after 1863.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, the population of the capital of St John's doubled from 15,000 in 1835 to 29,594 in 1901. The religious census of 1901 reported: Roman Catholics, 76,000; Church of England, 73,000; Methodists, 61,000; Presbyterians, 1,200; Congregationalists, 1,000; Salvationists, 6,600; Moravians, Baptists and others, 1,600. As part of the Anglo-French

As part of the Anglo-French Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

of 1904, France abandoned the `French Shore', or the west coast of the island, to which it had had rights since the Peace of Utrecht of 1713. Bond had helped negotiate the end of all French fishing rights, and was reelected in a landslide. Possession of Labrador was disputed by Quebec and Newfoundland until 1927, when the British Privy Council demarcated the western boundary, enlarged Labrador's land area, and confirmed Newfoundland's title to it.

The public education budget for Newfoundland in 1905 was $196,000, which covered 783 elementary schools and academies with 35,204 students. About 25% of the population, chiefly the older folk, were illiterate. The school system was denominational until the 1990s, with each church receiving grants in proportion to numerical strength.

Dominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland remained a colony until acquiringdominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

status on 26 September 1907, along with New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

. It successfully negotiated a trade agreement with the United States but the British government blocked it after objections from Canada. The Dominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland was a British dominion in eastern North America, today the modern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It was established on 26 September 1907, and confirmed by the Balfour Declaration of 1926 and the Statute of Westmi ...

reached its golden age under Prime Minister Sir Robert Bond

Sir Robert Bond (25 February 1857 – 16 March 1927) was the last Premier of Newfoundland Colony from 1900 to 1907 and the first prime minister of the Dominion of Newfoundland from 1907 to 1909 after the 1907 Imperial Conference conferred ...

of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

.

However, his efforts to restrict the rights of American fishermen failed, which led to his party to be badly defeated in 1909. Bond formed a coalition with the new Fishermen's Protective Union

The Fishermen's Protective Union (sometimes called the Fisherman's Protective Union, the FPU, The Union or the Union Party) was a workers' organisation and political party in the Dominion of Newfoundland. The development of the FPU mirrored that ...

(FPU), led by William Coaker

Sir William Ford Coaker (October 19, 1871 – October 26, 1938) was a Newfoundland union leader and politician and founder of the Fisherman's Protective Union, the Fishermen's Union Trading Co., and the town of Port Union. A polarizing figure ...

(1871–1938). Founded in 1908, the FPU worked to increase the incomes of fishermen by breaking the merchants' monopoly on the purchase and export of fish and the retailing of supplies, and tried to revitalize the fishery through state intervention. At its peak, it had more than 21,000 members in 206 councils across the island; more than half of Newfoundland's fishers. It appealed to Protestants and was opposed by Catholics. The FPU morphed into a political party in 1912, the Fisherman's Union party.

Bond was succeeded as premier by Edward Morris (1859–1935), a prominent Catholic and founder of the new People's Party. Morris began a grandiose program of building branch railways and adeptly handled the arbitration at the Hague tribunal on American fishing rights. He introduced old-age pensions and increased investment in education and rural infrastructure. In the prosperous and peaceful year of 1913 he was reelected. As a result of a wartime crisis over conscription, and the decline of his popularity due to accusations of wartime profiteering and conflict of interest, Morris set up an all-party war government in 1917 to oversee the duration of the war. He retired in 1917, moved to London, and was given a peerage as first Baron Morris, the only Newfoundlander ever so honored.

First World War

TheFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was supported with near unanimity in Newfoundland. Recruiting was brisk, with 6,240 men joining the Newfoundland Regiment

The Royal Newfoundland Regiment (R NFLD R) is a Primary Reserve infantry regiment of the Canadian Army. It is part of the 5th Canadian Division's 37 Canadian Brigade Group.

Predecessor units trace their origins to 1795, and since 1949 Royal New ...

for overseas duty, 1,966 joining the Royal Navy, 491 joined the Forestry Corps (which did lumberjack work at home), plus another 3,300 men joined Canadian units, and 40 women became war nurses. Without convening the legislature, Premier Morris and the royal governor, Sir Walter Davidson created the Newfoundland Patriotic Association, a non-partisan body involving both citizens and politicians, to supervise the war effort until 1917. With inflation soaring and corruption rampant, with the prohibition of liquor in effect and fears of conscription apparent, the Association gave way to an all-party National Government. The conscription issue was not as intense as in Canada, but it weakened the Fisherman's Union party, as its leaders supported conscription and most members opposed it. The Fisherman's party then merged into the Liberal-Unionist Party and faded away as an independent force.

During the great

During the great Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place be ...

in France in 1916, the British assaulted the German trenches near Beaumont Hamel. The 800-man Royal Newfoundland Regiment attacked as part of a British brigade. Most of the Newfoundlanders were killed or wounded without anyone in the regiment having fired a shot. The state, church, and press romanticized the sacrifice Newfoundlanders had made in the war effort through ceremonies, war literature, and memorials, the most important of which was the Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park, which opened in France in 1925. The story of the heroic sacrifice of the regiment in 1916 served as a cultural inspiration.

1919–1934

In 1919, the FPU joined with theLiberal Party of Newfoundland

The Liberal Party of Newfoundland and Labrador is a political party in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The party is the provincial branch, and affiliate of the federal Liberal Party of Canada. It has served as the Government ...

led by Richard Squires

Sir Richard Anderson Squires KCMG (January 18, 1880 – March 26, 1940) was the Prime Minister of Newfoundland from 1919 to 1923 and from 1928 to 1932.

As prime minister, Squires attempted to reform Newfoundland's fishing industry, but failed at ...

to form the Liberal Reform Party. The Liberal-Union coalition won 24 of 36 seats in the 1919 general election with half of the coalition's seats being won by Union candidates.

The 1920 Education Act set up a Department of Education, to oversee all state schools, including teacher training and certification. It provided for four grades of certificated teachers. There was also a category of other "ungraded" teachers, who were unqualified and employed on a temporary basis.

International capital was increasingly attracted by the island's natural resources. A Canadian firm opened iron mines in 1895 on Bell Island in Conception Bay. Paper mills were built at Grand Falls by the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company, a British firm, in 1909. British entrepreneurs set up a paper mill at Corner Brook in 1925 while the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company opened a lead-zinc mine on the Buchans River in 1927. In 1927, Britain awarded the vast, almost uninhabited hinterland of Labrador to Newfoundland rather than to Canada, adding potentially valuable new forest, hydroelectric, and mineral resources.

Politically the years from 1916 to 1925 were turbulent, as six successive governments failed, widespread corruption was uncovered, and the postwar boom ended in economic stagnation. Labour unions were active, as Joey Smallwood

Joseph Roberts Smallwood (December 24, 1900 – December 17, 1991) was a Newfoundlander and Canadian politician. He was the main force who brought the Dominion of Newfoundland into Canadian Confederation in 1949, becoming the first premier of ...

(1900–1991) founded the Newfoundland Federation of Labour

The Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Labour is the Newfoundland and Labrador provincial trade union federation for the Canadian Labour Congress. It was founded in 1937, and has a membership of 65,000.

The Newfoundland and Labrador Federati ...

in the early 1920s.

Newfoundland Commission of Government

Newfoundland's economic crash in theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, coupled with a profound distrust of politicians, led to the abandonment of self-government. Newfoundland remains the only nation that ever voluntarily relinquished democracy.

Economic collapse

Newfoundland's economy collapsed in theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, as prices plunged for fish, its main export. The population was 290,000, and the people and merchants were out of money. Since there was relatively little subsistence farming, people depended heavily on the meager supply of government relief, and as much emergency help with their friends, neighbors, and relatives could spare. There were no reports of starvation, but malnutrition was widespread.

The depression was hard on both the fishermen and merchants in Battle Harbour, Labrador, and they almost came to blows. The Baine, Johnston firm had to cut winter credit, whereupon poorer fishermen threatened the company with violence. Government relief payments were too scanty.

Political collapse

Baron Amulree

Baron Amulree, of Strathbraan in the County of Perth, was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 22 July 1929 for the lawyer and Labour politician Sir William Mackenzie. He was Secretary of State for Air

The Secre ...

, one of the three commissioners of the Newfoundland Royal Commission {{Short description, 1933 UK royal commission on Newfoundland finances

The Newfoundland Royal Commission or Amulree Commission (as it came to be known) was a royal commission established on February 17, 1933 by the Government of the United Kingdom ...

. Convened in 1933, the commission eventually recommended that the government be suspended for a period of time.

The government was bankrupt. It had borrowed heavily to construct and maintain a trans-island railway and to finance the country's regiment in the World War. By 1933, the public debt was over $100 million compared to a nominal national income of about $30 million. Interest payments on the debt absorbed 63% of government revenue and the budget deficit was $3.5 million or over 10 percent of the island's GDP. There was no more credit; a short-lived plan to sell Labrador to Canada fell through. The Richard Squires

Sir Richard Anderson Squires KCMG (January 18, 1880 – March 26, 1940) was the Prime Minister of Newfoundland from 1919 to 1923 and from 1928 to 1932.

As prime minister, Squires attempted to reform Newfoundland's fishing industry, but failed at ...

government was ineffective and when Squires was arrested for bribery in 1932 he fell from power.

A royal commission under Lord Amulree examined the causes of the financial disaster and concluded:

In return for British financial assistance, the newly elected government of Frederick Alderdice agreed to the appointment by London of a three-member royal commission, including British, Canadian, and Newfoundland nominees. The Newfoundland Royal Commission, chaired by Lord Amulree, recommended that Britain "assume general responsibility" for Newfoundland's finances. Newfoundland would give up self-government in favour of administration by an appointed governor and a six-member appointed Commission of Government, having both executive and legislative authority. The solution was designed to provide "a rest from politics" and a government free of corruption. The legislature accepted the deal, formalized when the British Parliament passed the Newfoundland Act, 1933. In 1934, the Commission of Government took control; its six appointed commissioners, who administered the country without elections. It lasted until 1949. "On 16 February 1934, Premier Alderdice signed the papers that surrendered Newfoundland's dominion status," reports historian Sean Cadigan.

Second World War

In 1940

In 1940 Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

and Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed to an exchange of American destroyers for access to British naval bases in the Atlantic, including Newfoundland. The result was sudden prosperity as American money flooded the island, where 25% of the people had recently been on relief. Some 20,000 men were employed in building military bases. The local and British governments persuaded the United States to keep wages low so as to not destroy the labor force for fishing, logging and other local industries, but the cost of living—already higher than in Canada or the United States—rose 58% between 1938 and 1945. Even more influential was the sudden impact of a large modern American population on a traditional society. American ideas regarding food, hygiene (and indoor plumbing), entertainment, clothing, living standards and pay scales swept the island. As during World War I, Newfoundland became vital to the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

. Each month dozens of naval ships protecting convoys stopped at St. John's.

Postwar

America retained and expanded its Newfoundland bases after the war, because the island was on the shortestGreat Circle

In mathematics, a great circle or orthodrome is the circular intersection of a sphere and a plane passing through the sphere's center point.

Any arc of a great circle is a geodesic of the sphere, so that great circles in spherical geome ...

air route between the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

, and Soviet bombers carrying nuclear weapons was the largest threat to American cities. Its five large American bases—four Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

and one Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

—were important to Newfoundland's economy, and many Americans intermarried with native residents.

Fears of a permanent American presence in Newfoundland caused the Canadian government to attempt to persuade the island to join the Canadian Confederation. This was not primarily due to economic reasons. In the 1940s Newfoundland was Canada's eighth-largest trading partner. The island primarily traded with Britain and the United States, especially the "Boston states

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provi ...

" of New England. Canada saw some value in Newfoundland's fisheries, raw materials, Labrador's hydroelectric potential, and 300,000 people of English and Irish descent, and expected that its location would remain important to trans-Atlantic aviation.

Canada's primary interest, however, was from the fear that an independent Newfoundland would join the United States due to their economic and military ties. With Newfoundland, the United States would block the Gulf of St. Lawrence and leave only about 500 km of Nova Scotia coastline open to the Atlantic. Because America already bordered Canada on the south

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

and controlled all but about 600 km of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

's western boundary, Canada would be almost surrounded on three sides. Both Britain and Canada wished to prevent this. Newfoundlanders had regained their prosperity and their self-confidence, but were uncertain whether they should be an independent nation with close ties to the United States, or become part of Canada.

Referendum

As soon as prosperity returned during the war, agitation began to end the Commission. Newfoundland, with a population of 313,000 (plus 5,200 in Labrador), seemed too small to be independent.Joey Smallwood

Joseph Roberts Smallwood (December 24, 1900 – December 17, 1991) was a Newfoundlander and Canadian politician. He was the main force who brought the Dominion of Newfoundland into Canadian Confederation in 1949, becoming the first premier of ...

was a well-known radio personality, writer, organizer, and nationalist who long had criticized British rule. In 1945 London announced that a Newfoundland National Convention would be elected to advise on what constitutional choices should to be voted on by referendum. Union with the United States was a possibility, but Britain rejected the option and offered instead two options, return to dominion status or continuation of the unpopular Commission. Canada cooperated with Britain to ensure that the option of closer ties with America was not on the referendum.

Canada issued an invitation to join it on generous financial terms. Smallwood was elected to the convention where he became the leading proponent of confederation with Canada, insisting, "Today we are more disposed to feel that our very manhood, our very creation by God, entitles us to standards of life no lower than our brothers on the mainland." Displaying a mastery of propaganda technique, courage and ruthlessness, he succeeded in having the Canada option on the referendum. His main opponents were

Canada issued an invitation to join it on generous financial terms. Smallwood was elected to the convention where he became the leading proponent of confederation with Canada, insisting, "Today we are more disposed to feel that our very manhood, our very creation by God, entitles us to standards of life no lower than our brothers on the mainland." Displaying a mastery of propaganda technique, courage and ruthlessness, he succeeded in having the Canada option on the referendum. His main opponents were Peter John Cashin

Major Peter John Cashin (March 8, 1890 – May 21, 1977) was a businessman, soldier and politician in Newfoundland.

Early life

Cashin, a son of Sir Michael Cashin, joined the Newfoundland Regiment during World War I and ultimately served in th ...

and Chesley Crosbie. Cashin, a former finance minister, led the Responsible Government League, warning against cheap Canadian imports and the high Canadian income tax. Crosbie, a leader of the fishing industry, led the Party for Economic Union with the United States, seeking responsible government first, to be followed by closer ties with the United States, which could be a major source of capital.

Smallwood's side was victorious in a referendum and a runoff in June–July 1948, as the choice of joining Canada defeated becoming an independent dominion, 78,323 (52.3%) to 71,334 (47.7%). A strong rural vote in favour of Canada exceeded the pro-independence vote in St. John's. The Irish Catholics in the city desired independence in order to protect their parochial schools, leading to a Protestant backlash in rural areas. The promise of cash family allowances from Canada proved decisive.

Not everyone was satisfied with the results, however. Cashin, an outspoken anti-Confederate, questioned the validity of the votes. He claimed that it was the 'unholy union between London and Ottawa' that brought about confederation.

Post-Confederation history

AfterICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons ...

s replaced the bomber threat in the late 1950s, the American Air Force bases closed by the early 1960s and Naval Station Argentia

Naval Station Argentia is a former base of the United States Navy that operated from 1941 to 1994. It was established in the community of Argentia in what was then the Dominion of Newfoundland, which later became the tenth Canadian province, Ne ...

in the 1980s. In 1959, a local controversy arose when the provincial government pressured the Moravian Church

The Moravian Church ( cs, Moravská církev), or the Moravian Brethren, formally the (Latin: "Unity of the Brethren"), is one of the oldest Protestantism, Protestant Christian denomination, denominations in Christianity, dating back to the Bohem ...

to abandon its mission station at Hebron, Labrador, resulting in the relocation southward of the area's Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

population, who had lived there since the mission was established in 1831.

Mid- to late-20th century economy

Considerable attention was paid to the infrastructure for Labrador, especially building railway systems to transport the minerals and raw materials from Labrador to Quebec, and an electricity grid. In the 1960s, the province developed the Churchill Falls hydro-electric facility in order to sell electricity to the United States. An agreement with Quebec was required to secure permission to transport the electricity across Quebec territory. Quebec drove a hard bargain with Newfoundland, resulting in a 75-year deal that Newfoundlanders now believe to be unfair to the province because of the low and unchangeable rate that it receives for the electricity. In addition to energy production, iron mining did not begin in Labrador until the 1950s. By 1990, the Quebec-Labrador area had become an important supplier of iron ore to the United States.

In the late 1980s, the federal government, along with its

Considerable attention was paid to the infrastructure for Labrador, especially building railway systems to transport the minerals and raw materials from Labrador to Quebec, and an electricity grid. In the 1960s, the province developed the Churchill Falls hydro-electric facility in order to sell electricity to the United States. An agreement with Quebec was required to secure permission to transport the electricity across Quebec territory. Quebec drove a hard bargain with Newfoundland, resulting in a 75-year deal that Newfoundlanders now believe to be unfair to the province because of the low and unchangeable rate that it receives for the electricity. In addition to energy production, iron mining did not begin in Labrador until the 1950s. By 1990, the Quebec-Labrador area had become an important supplier of iron ore to the United States.

In the late 1980s, the federal government, along with its Crown corporation

A state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a government entity which is established or nationalised by the ''national government'' or ''provincial government'' by an executive order or an act of legislation in order to earn profit for the government ...

Petro-Canada

Petro-Canada is a retail and wholesale marketing brand subsidiary of Suncor Energy. Until 1991, it was a federal Crown corporation (a state-owned enterprise). In August 2009, Petro-Canada merged with Suncor Energy, with Suncor shareholders rec ...

and other private sector petroleum exploration companies, committed to developing the oil and gas resources of the Hibernia

''Hibernia'' () is the Classical Latin name for Ireland. The name ''Hibernia'' was taken from Greek geographical accounts. During his exploration of northwest Europe (c. 320 BC), Pytheas of Massalia called the island ''Iérnē'' (written ). ...

oil field on the northeast portion of the Grand Banks

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, sword ...

. Throughout the mid-1990s, thousands of Newfoundlanders were employed on offshore exploration platforms, as well as in the construction of the Hibernia Gravity Base Structure (GBS) and Hibernia topsides.

Fishing

Around 1900 the average annual export of dried cod-fish over a term of years was about 120,000,000 kilograms, with a value between five and six million dollars. The cod were caught on the shores of the island, along the Labrador coast and especially on "the Banks." These Banks stretch for about 300 m. in a south-east direction towards the centre of the North Atlantic; depths range from 15 to 80 fathoms (25–150 meters). In 1901, 28% of the labor force was engaged in the catching and curing of fish, compared to 31% in 1857. They used 1550 small boats, with a tonnage of 54,500. The cod were taken by the hook-and-line, the seine, the cod-net or gill-net, the cod-trap and the bultow; Brazil and Spain were the largest customers. Cod, supplemented by herring and lobster, remained an economic mainstay until the late 20th century. After 1945, the fishing economy was transformed from a predominantly labor-intensive inshore, household-based, saltfish-producing enterprise into an industrialized economy dominated by vertically integrated frozen fish companies. These efficient companies needed fewer workers, so about 300 fishing villages, or outports, were abandoned by their residents between 1954 and 1975 as part of a Canadian government-sponsored program known as the Resettlement. Some areas lost 20% of their population, and enrollment in schools dropped even more. In the 1960s some 2 billion pounds of cod were harvested annually from the Grand Bank off Newfoundland, the world's largest source of fish. Then disaster hit. The northern cod practically vanished—they were reduced to 1% of their historic spawning biomass. In 1992, the cod fishery was shut down by the Canadian government; cod fishing as a way of life came to an end for 19,000 workers after a 500-year history as a main industry. However, the situation changed in the 1990s as a result of the

However, the situation changed in the 1990s as a result of the collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery

In 1992, Northern Cod populations fell to 1% of historical levels, due in large part to decades of overfishing. The Canadian Federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, John Crosbie, declared a moratorium on the Northern Cod fishery, which fo ...

. In 1992, the federal government declared a moratorium on the Atlantic cod fishery, because of severely declining catches in the late 1980s. The consequences of this decision reverberated throughout the provincial economy of Newfoundland in the 1990s, particularly as once-vibrant rural communities faced a sudden exodus. The economic impact of the closure of the Atlantic cod fishery on Newfoundland has been compared to the effect of closing every manufacturing plant in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

. The cod fishery which had provided Newfoundlanders on the south and east coasts with a livelihood for over 200 years was gone, although the federal government helped fishermen and fish plant workers make the adjustment with a multibillion-dollar program named "The Atlantic Groundfish Strategy" (''TAGS'').

Tourism

Starting in the 1990s tourism was promoted by many local development, heritage and archaeological organisations as a way of restoring the economic base of many outports and villages. Limited, short-term funding for some tourism-related projects came from government programs designed to maintain morale and find a new economic role.Whale hunting

Whale hunting became an important industry around 1900. At first slow whales were caught by men hurling harpoons from small open boats. Mechanization copied from Norway brought in cannon-fired harpoons, strong cables, and steam winches mounted on maneuverable, steam-powered catcher boats. They made possible the targeting of large and fast-swimming whale species that were taken to shore-based stations for processing. The invention of the harpoon cannon in the 1860s and the westward expansion of the Scandinavian industry that resulted from the rapid depletion of their local stocks resulted in the emergence of the modern whaling industry off Newfoundland and Labrador. The industry was highly cyclical, with well-defined catch peaks in 1903–05, 1925–30, 1945–51, and 1966–72, after which world-wide bans shut it down. When Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, it relinquished jurisdiction over its fisheries to Ottawa; the Supreme Court ruled in 1983 that the federal government also has jurisdiction over offshore oil drilling.Politics in the mid- to late-20th century

Neary (1980) identifies three postwar political eras, each marked by a dramatic opening event. A first period began with confederation, with Smallwood in power. A second period of politics started with the Progressive Conservative victory in the federal general election of 1957. A third period began with the sweeping Conservative victory in Newfoundland in the federal election of 1968. There was a common theme in each era, involving the continuing decline of the traditional, stable, subsistence, outport economy by the forces of urbanism and industrialism. Politics was dominated by theLiberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, led by Premier Smallwood, from confederation until 1972.Frederick W. Rowe, ''The Smallwood Era'' (1985) His main program was economic growth, and creating new jobs to encourage young people to stay in Newfoundland. Smallwood made major efforts to modernize the fishing industry, to create a new energy industry, and to attract factories. He vigorously promoted economic development through the Economic Development Plan of 1951, championed the welfare state (paid for by Ottawa), and attracted favorable attention across Canada. He emphasized modernisation of education and transportation in order to attract outsiders, such as German industrialists, because the local economic elite would not invest in industrial development. Smallwood dropped his youthful socialism and collaborated with bankers, and became hostile to the militant unions that sponsored numerous strikes. His efforts to promote industrialization were partially successful, with great success primarily in hydroelectricity, iron mining, and paper mills. Smallwood also upgraded the small Memorial University College in St John's, founded in 1925, to Memorial University of Newfoundland

Memorial University of Newfoundland, also known as Memorial University or MUN (), is a public university in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, based in St. John's, with satellite campuses in Corner Brook, elsewhere in Newfoundland and ...

(MUN) in 1949, with free tuition and a cash stipend for students.

Smallwood's style was autocratic and highly personalized, as he totally controlled his party. Meanwhile, the demoralized anti-confederates became the provincial wing of the Progressive Conservative Party. An extension of the Trans-Canada Highway

The Trans-Canada Highway (Canadian French, French: ; abbreviated as the TCH or T-Can) is a transcontinental federal–provincial highway system that travels through all ten provinces of Canada, from the Pacific Ocean on the west coast to the A ...

became the first paved road across the island in 1966. That year Smallwood's government heavily advertised a "Come Home" program to attract as tourists Newfoundland expatriates, such as war brides in the United States and those who had left for work. The goal was to demonstrate the changes during the Smallwood era in the province's economy and infrastructure.

In 1972, the Smallwood government was replaced by the Progressive Conservative administration of Frank Moores

Frank Duff Moores (February 18, 1933 – July 10, 2005) served as the second premier of Newfoundland. He served as leader of the Progressive Conservatives from 1972 until his retirement in 1979. Moores was also a successful businessman in bo ...

. In 1979, Brian Peckford

Alfred Brian Peckford (born August 27, 1942) is a Canadian politician who served as the third premier of Newfoundland from March 26, 1979 to March 22, 1989. A member of the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party, Peckford was first elected as the ...

, another Progressive Conservative, became Premier. During this time, Newfoundland was involved in a dispute with the federal government for control of offshore oil resources. In the end, the dispute was decided by compromise. In 1989, Clyde Wells and the Liberal Party returned to power ending 17 years of Conservative government.

The fishing crisis of the 1990s saw the already precarious economic base of the many towns further eroded. The situation was made worse by both federal and provincial pursuit of programs of economic liberalization that sought to limit the role of the state in economic and social affairs. As the effects of the crisis were felt, and established state supports were weakened, tourism was embraced by a growing body of local development and heritage organizations as a way of restoring the shattered economic base of many communities. Limited, short-term funding for some tourism-related projects was provided mostly from government programs, largely as a means of politically managing the structural adjustment that was being pursued.James Overton, "'A Future in the Past'? Tourism Development, Outport Archaeology, and the Politics of Deindustrialization in Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1990s." ''Urban History Review'' 2007 35(2): 60–74.

In 1996, the former federal minister of fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, ...

, Brian Tobin

Brian Vincent Tobin (born October 21, 1954) is a Canadian businessman and former politician. Tobin served as the sixth premier of Newfoundland from 1996 to 2000. Tobin was also a prominent Member of Parliament and served as a cabinet minister ...

, was successful in winning the leadership of the provincial Liberal Party following the retirement of premier Clyde Wells. Tobin rode the waves of economic good fortune as the downtrodden provincial economy was undergoing a fundamental shift, largely as a result of the oil and gas industry's financial stimulus, although the effects of this were mainly felt only in communities on the Avalon Peninsula. Good fortune also fell on Tobin following the discovery of a world class nickel deposit at Voisey's Bay, Labrador. Tobin committed to negotiating a better royalty deal for the province with private sector mining interests than previous governments had done with the Churchill Falls hydroelectric development deal in the 1970s. Following Tobin's return to federal politics in 2000, the provincial Liberal Party devolved into internal battling for the leadership, leaving its new leader, Roger Grimes

Roger D. Grimes (born May 2, 1950) is a Canadian politician from Newfoundland and Labrador. Grimes was born and raised in the central Newfoundland town of Grand Falls-Windsor.

Grimes is a former leader of the province's Liberal Party and was its ...

, in a weakened position as premier.

21st century

The pressure of the oil and gas industry to explore offshore in Atlantic Canada saw Newfoundland andNova Scotia