The history of Lithuania dates back to settlements founded many thousands of years ago, but the first written record of the name for the country dates back to 1009 AD.

Lithuanians

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Unite ...

, one of the

Baltic peoples, later conquered neighboring lands and established the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was Partitions of Poland, partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire, Habsburg Empire of ...

in the 13th century (and also a short-lived

Kingdom of Lithuania). The Grand Duchy was a successful and lasting warrior state. It remained fiercely independent and was one of the last areas of Europe to

adopt Christianity (beginning in the 14th century). A formidable power, it became the largest state in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

in the 15th century through the conquest of large groups of

East Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert ...

who resided in

Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

. In 1385, the Grand Duchy formed a

dynastic union with

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

through the

Union of Krewo. Later, the

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

(1569) created the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

that lasted until 1795, when the last of the

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

erased both Lithuania and Poland from the political map. After the

dissolution, Lithuanians lived under the rule of the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

until the 20th century, although there were several major rebellions, especially in

1830–1831 and

1863.

On 16 February 1918,

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

was re-established as a democratic state. It remained independent until the outset of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, when it was occupied by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

under the terms of the

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

. Following a brief occupation by

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

after the Nazis

waged war on the Soviet Union, Lithuania was again

absorbed into the Soviet Union for nearly 50 years. In 1990–1991, Lithuania restored its sovereignty with the

Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania

The Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania or Act of March 11 ( lt, Aktas dėl Lietuvos nepriklausomos valstybės atstatymo) was an independence declaration by Lithuania adopted on March 11, 1990, signed by all members of the ...

. Lithuania joined the

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

alliance in 2004 and the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

as part of

its enlargement in 2004.

Before statehood

Early settlement

The first humans arrived on the territory of modern Lithuania in the second half of the 10th millennium BC after the glaciers receded at the end of the

last glacial period. According to the historian

Marija Gimbutas

Marija Gimbutas ( lt, Marija Gimbutienė, ; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994) was a Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist known for her research into the Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of " Old Europe" and for her Kurgan hypothesis ...

, these people came from two directions: the

Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

Peninsula and from present-day

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. They brought two different cultures, as evidenced by the tools they used. They were traveling hunters and did not form stable settlements. In the 8th millennium BC, the climate became much warmer, and forests developed. The inhabitants of what is now Lithuania then traveled less and engaged in local hunting, gathering and fresh-water fishing. During the 6th–5th millennium BC, various animals were domesticated and dwellings became more sophisticated in order to shelter larger families. Agriculture did not emerge until the 3rd millennium BC due to a harsh climate and terrain and a lack of suitable tools to cultivate the land. Crafts and trade also started to form at this time.

Speakers of North-Western

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

might have arrived with the

Corded Ware culture around 3200/3100 BC.

Baltic tribes

The first

Lithuanian people were a branch of an ancient group known as the

Balts

The Balts or Baltic peoples ( lt, baltai, lv, balti) are an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak the Baltic languages of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages.

One of the features of Baltic languages is the number ...

. The main tribal divisions of the Balts were the West Baltic

Old Prussians and

Yotvingians, and the East Baltic Lithuanians and

Latvians

Latvians ( lv, latvieši) are a Baltic ethnic group and nation native to Latvia and the immediate geographical region, the Baltics. They are occasionally also referred to as Letts, especially in older bibliography. Latvians share a common L ...

. The Balts spoke forms of the

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, D ...

.

[ Krzysztof Baczkowski – ''Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506)'' istory of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506) pp. 55–61; Fogra, Kraków 1999, ] Today, the only remaining Baltic nationalities are the Lithuanians and Latvians, but there were more Baltic groups or tribes in the past. Some of these merged into Lithuanians and Latvians (

Samogitians,

Selonians

The Selonians ( lv, sēļi; lt, sėliai, from liv, sälli – "highlanders") were a tribe of Baltic peoples. They lived until the 15th century in Selonia, located in southeastern Latvia and northeastern Lithuania. They eventually merged wit ...

,

Curonians

:''The Kursenieki are also sometimes known as Curonians.''

The Curonians or Kurs ( lv, kurši; lt, kuršiai; german: Kuren; non, Kúrir; orv, кърсь) were a Baltic tribe living on the shores of the Baltic Sea in what are now the western ...

,

Semigallians), while others no longer existed after they were conquered and assimilated by the

State of the Teutonic Order

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Cent ...

(Old Prussians, Yotvingians,

Sambians,

Skalvians, and

Galindians).

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 23]

The

Baltic tribes did not maintain close cultural or political contacts with the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, but they did maintain trade contacts (see

Amber Road

The Amber Road was an ancient trade route for the transfer of amber from coastal areas of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Prehistoric trade routes between Northern and Southern Europe were defined by the amber trade.

...

).

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, in his study ''

Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north-c ...

'', described the

Aesti people, inhabitants of the south-eastern

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

shores who were probably Balts, around the year 97 AD.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 22] The Western Balts differentiated and became known to outside chroniclers first.

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

in the 2nd century AD knew of the Galindians and Yotvingians, and

early medieval chroniclers mentioned Prussians, Curonians and Semigallians.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 26]

Lithuania, located along the lower and middle

Neman River

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ; ...

basin, comprised mainly the culturally different regions of

Samogitia (known for its early medieval skeletal burials), and further east

Aukštaitija

Aukštaitija (; literally in Lithuanian: ''Upper lands'') is the name of one of five ethnographic regions of Lithuania. The name comes from lands being in upper basin of Nemunas River or being relative to Lowlands up to Šiauliai.

Geography

Auk ...

, or Lithuania proper (known for its early medieval cremation burials).

[Ochmański (1982), p. 37] The area was remote and unattractive to outsiders, including traders, which accounts for its separate linguistic, cultural and religious identity and delayed integration into general European patterns and trends.

The

Lithuanian language

Lithuanian ( ) is an Eastern Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is the official language of Lithuania and one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.8 mill ...

is considered to be very

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

for its close connection to Indo-European roots. It is believed to have differentiated from the

Latvian language

Latvian ( ), also known as Lettish, is an Eastern Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family, spoken in the Baltic region. It is the language of Latvians and the official language of Latvia as well ...

, the most closely related existing language, around the 7th century.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 13] Traditional

Lithuanian pagan customs and mythology, with many archaic elements, were long preserved. Rulers' bodies were cremated up until the

Christianization of Lithuania: the descriptions of the cremation ceremonies of the grand dukes

Algirdas

Algirdas ( be, Альгерд, Alhierd, uk, Ольгерд, Ольґерд, Olherd, Olgerd, pl, Olgierd; – May 1377) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania. He ruled the Lithuanians and Ruthenians from 1345 to 1377. With the help of his br ...

and

Kęstutis have survived.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 24–25]

The Lithuanian tribe is thought to have developed more recognizably toward the end of the first

millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannus, kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting ...

.

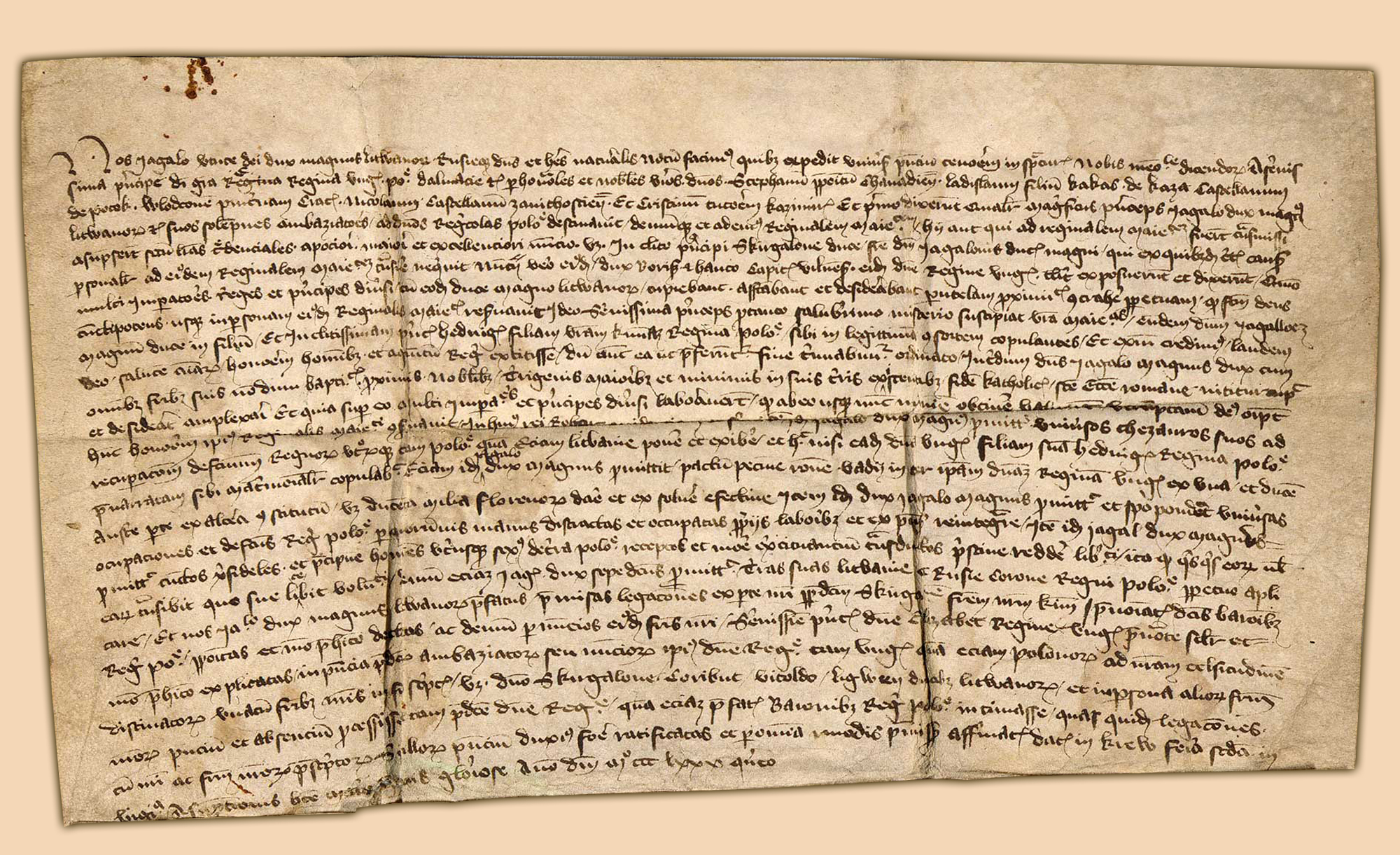

The first known reference to Lithuania as a nation ("Litua") comes from the

Annals of the Quedlinburg monastery, dated 9 March 1009. In 1009, the missionary

Bruno of Querfurt arrived in Lithuania and baptized the Lithuanian ruler "King Nethimer."

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 22, 26–28]

Formation of a Lithuanian state

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, coastal Balts were subjected to raids by the

Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

, and the kings of

Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

collected tribute at times. During the 10–11th centuries, Lithuanian territories were among the lands paying tribute to

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

, and

Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav the Wise or Yaroslav I Vladimirovich; russian: Ярослав Мудрый, ; uk, Ярослав Мудрий; non, Jarizleifr Valdamarsson; la, Iaroslaus Sapiens () was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death. He was al ...

was among the

Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

n rulers who invaded Lithuania (from 1040). From the mid-12th century, it was the Lithuanians who were invading Ruthenian territories. In 1183,

Polotsk and

Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=pskov-ru.ogg, p=pskof; see also names in other languages) is a city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, located about east of the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population ...

were ravaged, and even the distant and powerful

Novgorod Republic

The Novgorod Republic was a medieval state that existed from the 12th to 15th centuries, stretching from the Gulf of Finland in the west to the northern Ural Mountains in the east, including the city of Novgorod and the Lake Ladoga regions of mod ...

was repeatedly threatened by the excursions from the emerging Lithuanian war machine toward the end of the 12th century.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 39–42]

In the 12th century and afterwards, mutual raids involving Lithuanian and Polish forces took place sporadically, but the two countries were separated by the lands of the

Yotvingians. The late 12th century brought an eastern expansion of German settlers (the

Ostsiedlung

(, literally "East-settling") is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration-period when ethnic Germans moved into the territories in the eastern part of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire (that Germans had a ...

) to the mouth of the

Daugava River

, be, Заходняя Дзвіна (), liv, Vēna, et, Väina, german: Düna

, image = Fluss-lv-Düna.png

, image_caption = The drainage basin of the Daugava

, source1_location = Valdai Hills, Russia

, mouth_location = Gulf of Riga, Baltic S ...

area. Military confrontations with Lithuanians followed at that time and at the turn of the century, but for the time being the Lithuanians had the upper hand.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 43–45]

From the late 12th century, an organized Lithuanian military force existed; it was used for external raids, plundering and the gathering of slaves. Such military and pecuniary activities fostered social differentiation and triggered a struggle for power in Lithuania. This initiated the formation of early statehood, from which the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was Partitions of Poland, partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire, Habsburg Empire of ...

developed.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania (13th century–1569)

13th–14th century Lithuanian state

Mindaugas and his kingdom

From the early 13th century, frequent foreign military excursions became possible due to the increased cooperation and coordination among the Baltic tribes.

Forty such expeditions took place between 1201 and 1236 against Ruthenia, Poland, Latvia and Estonia, which were then being conquered by the

Livonian Order

The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order,

formed in 1237. From 1435 to 1561 it was a member of the Livonian Confederation.

History

The order was formed from the remnants of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword after th ...

.

Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=pskov-ru.ogg, p=pskof; see also names in other languages) is a city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, located about east of the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population ...

was pillaged and burned in 1213.

In 1219, twenty-one Lithuanian chiefs signed a peace treaty with the state of

Galicia–Volhynia. This event is widely accepted as the first proof that the Baltic tribes were uniting and consolidating.

From the early 13th century, two German crusading

military orders, the

Livonian Brothers of the Sword

The Livonian Brothers of the Sword ( la, Fratres militiæ Christi Livoniae, german: Schwertbrüderorden) was a Catholic military order established in 1202 during the Livonian Crusade by Albert, the third bishop of Riga (or possibly by Theoderi ...

and the

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

, became established at the mouth of the

Daugava River

, be, Заходняя Дзвіна (), liv, Vēna, et, Väina, german: Düna

, image = Fluss-lv-Düna.png

, image_caption = The drainage basin of the Daugava

, source1_location = Valdai Hills, Russia

, mouth_location = Gulf of Riga, Baltic S ...

and in

Chełmno Land

Chełmno land ( pl, ziemia chełmińska, or Kulmerland, Old Prussian: ''Kulma'', lt, Kulmo žemė) is a part of the historical region of Pomerelia, located in central-northern Poland.

Chełmno land is named after the city of Chełmno (hist ...

respectively. Under the pretense of converting the population to Christianity, they proceeded to conquer much of the area that is now Latvia and

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

, in addition to parts of Lithuania.

In response, a number of small Baltic tribal groups united under the rule of

Mindaugas. Mindaugas, originally a ''kunigas'' or major chief, one of the five

senior dukes listed in the treaty of 1219, is referred to as the ruler of all Lithuania as of 1236 in the

Livonian Rhymed Chronicle.

In 1236 the pope declared a crusade against the Lithuanians.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 29–30] The

Samogitians, led by

Vykintas, Mindaugas' rival,

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 46–47] soundly defeated the Livonian Brothers and their allies in the

Battle of Saule

The Battle of Saule ( lt, Saulės mūšis / Šiaulių mūšis; german: Schlacht von Schaulen; lv, Saules kauja) was fought on 22 September 1236, between the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and pagan troops of Samogitians and Semigallians. Betwe ...

in 1236, which forced the Brothers to merge with the Teutonic Knights in 1237.

But Lithuania was trapped between the two branches of the Order.

Around 1240, Mindaugas ruled over all of

Aukštaitija

Aukštaitija (; literally in Lithuanian: ''Upper lands'') is the name of one of five ethnographic regions of Lithuania. The name comes from lands being in upper basin of Nemunas River or being relative to Lowlands up to Šiauliai.

Geography

Auk ...

. Afterwards, he conquered the

Black Ruthenia

Black Ruthenia ( la, Ruthenia Nigra), or Black Rus' ( be, Чорная Русь, translit=Čornaja Ruś; lt, Juodoji Rusia; pl, Ruś Czarna), is a historical region on the Upper Nemunas, including Novogrudok (Naugardukas), Grodno (Gardinas) a ...

region (which consisted of

Grodno

Grodno (russian: Гродно, pl, Grodno; lt, Gardinas) or Hrodna ( be, Гродна ), is a city in western Belarus. The city is located on the Neman River, 300 km (186 mi) from Minsk, about 15 km (9 mi) from the Polish b ...

,

Brest,

Navahrudak

Novogrudok ( be, Навагрудак, Navahrudak; lt, Naugardukas; pl, Nowogródek; russian: Новогрудок, Novogrudok; yi, נאַוואַראַדאָק, Novhardok, Navaradok) is a town in the Grodno Region, Belarus.

In the Middle A ...

and the surrounding territories).

Mindaugas was in process of extending his control to other areas, killing rivals or sending relatives and members of rival clans east to Ruthenia so they could conquer and settle there. They did that, but they also rebelled. The Ruthenian duke

Daniel of Galicia sensed an occasion to recover Black Ruthenia and in 1249–1250 organized a powerful anti-Mindaugas (and "anti-pagan") coalition that included Mindaugas' rivals, Yotvingians, Samogitians and the

Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

n Teutonic Knights. Mindaugas, however, took advantage of the divergent interests in the coalition he faced.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 47–48]

In 1250, Mindaugas entered into an agreement with the Teutonic Order; he consented to receive baptism (the act took place in 1251) and relinquish his claim over some lands in western Lithuania, for which he was to receive a royal crown in return.

Mindaugas was then able to withstand a military assault from the remaining coalition in 1251, and, supported by the Knights, emerge as a victor to confirm his rule over Lithuania.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 48–50]

On 17 July 1251,

Pope Innocent IV signed two

papal bulls that ordered the Bishop of

Chełmno to crown Mindaugas as

King of Lithuania, appoint a bishop for Lithuania, and build a cathedral.

In 1253, Mindaugas was crowned and a

Kingdom of Lithuania was established for the first and only time in Lithuanian history.

[Lithuania profile: history.](_blank)

U.S. Department of State Background Notes. Last accessed on 02 June 2013 Mindaugas "granted" parts of Yotvingia and Samogitia that he did not control to the Knights in 1253–1259. A peace with Daniel of Galicia in 1254 was cemented by a marriage deal involving Mindaugas' daughter and Daniel's son

Shvarn. Mindaugas' nephew

Tautvilas returned to his

Duchy of Polotsk and Samogitia separated, soon to be ruled by another nephew,

Treniota.

In 1260, the Samogitians, victorious over the Teutonic Knights in the

Battle of Durbe

The Battle of Durbe ( lv, Durbes kauja, lt, Durbės mūšis, german: Schlacht an der Durbe) was a medieval battle fought near Durbe, east of Liepāja, in present-day Latvia during the Livonian Crusade. On 13 July 1260, the Samogitians sound ...

, agreed to submit themselves to Mindaugas' rule on the condition that he abandons the Christian religion; the king complied by terminating the emergent conversion of his country, renewed anti-Teutonic warfare (in the struggle for Samogitia)

and expanded further his Ruthenian holdings.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 50–53] It is not clear whether this was accompanied by his personal

apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 33] Mindaugas thus established the basic tenets of medieval Lithuanian policy: defense against the German Order expansion from the west and north and conquest of

Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

in the south and east.

Mindaugas was the principal founder of the Lithuanian state. He established for a while a Christian kingdom under the pope rather than the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, at a time when the remaining pagan peoples of Europe were no longer being converted peacefully, but conquered.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 30–33]

Traidenis, Teutonic conquests of Baltic tribes

Mindaugas was murdered in 1263 by

Daumantas of Pskov and

Treniota, an event that resulted in great unrest and civil war. Treniota, who took over the rule of the Lithuanian territories, murdered Tautvilas, but was killed himself in 1264. The rule of Mindaugas' son

Vaišvilkas

Vaišvilkas or Vaišelga (also spelled as ''Vaišvila'', ''Vojszalak'', ''Vojšalk'', ''Vaišalgas''; killed on 18 April 1267) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1264–1267). He was son of Mindaugas, the first and only Christian King of Lithu ...

followed. He was the first Lithuanian duke known to become an

Orthodox Christian and settle in Ruthenia, establishing a pattern to be followed by many others.

Vaišvilkas was killed in 1267. A power struggle between Shvarn and

Traidenis resulted; it ended in a victory for the latter. Traidenis' reign (1269–1282) was the longest and most stable during the period of unrest. Tradenis reunified all Lithuanian lands, repeatedly raided Ruthenia and Poland with success, defeated the Teutonic Knights in Prussia and in Livonia at the

Battle of Aizkraukle in 1279. He also became the ruler of Yotvingia, Semigalia and eastern Prussia. Friendly relations with Poland followed, and in 1279, Tradenis' daughter

Gaudemunda of Lithuania

Gaudemunda Sophia of Lithuania (also Gaudimantė; c. 1260 – 1288 or 1313) was the daughter of Traidenis, Grand Duke of Lithuania (c. 1270–1282). In 1279 she married Duke of Masovia Bolesław II (c. 1254–1313) of the Piast dynasty. He was th ...

married

Bolesław II of Masovia

Bolesław II of Masovia or Bolesław II of Płock (pl: ''Bolesław II mazowiecki (płocki)''; ca. 1253/58 – 20 April 1313), was a Polish prince, member of the House of Piast, Duke of Masovia during 1262-1275 jointly with his brother, after 1 ...

, a

Piast duke.

Pagan Lithuania was a target of

northern Christian crusades of the Teutonic Knights and the

Livonian Order

The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order,

formed in 1237. From 1435 to 1561 it was a member of the Livonian Confederation.

History

The order was formed from the remnants of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword after th ...

.

In 1241, 1259 and 1275, Lithuania was also ravaged by raids from the

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmen ...

, which earlier (1237–1240)

debilitated Kievan Rus'.

After Traidenis' death, the German Knights finalized their conquests of Western Baltic tribes, and they could concentrate on Lithuania,

especially on Samogitia, to connect the two branches of the Order.

A particular opportunity opened in 1274 after the conclusion of the

Great Prussian Rebellion

The Prussian uprisings were two major and three smaller uprisings by the Old Prussians, one of the Baltic tribes, against the Teutonic Knights that took place in the 13th century during the Prussian Crusade. The crusading military order, suppor ...

and the conquest of the Old Prussian tribe. The Teutonic Knights then proceeded to conquer other Baltic tribes: the

Nadruvians

The Nadruvians were a now-extinct Prussian tribe. They lived in Nadruvia (alternative spellings include: ''Nadruva'', ''Nadrowite'', ''Nadrovia'', ''Nadrauen'', ''Nadravia'', ''Nadrow'' and ''Nadra''), a large territory in northernmost Prussia. Th ...

and

Skalvians in 1274–1277 and the

Yotvingians in 1283. The Livonian Order completed its conquest of Semigalia, the last Baltic ally of Lithuania, in 1291.

Vytenis, Lithuania's great expansion under Gediminas

The

family of Gediminas, whose members were about to form Lithuania's

great native dynasty,

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 34] took over the rule of the Grand Duchy in 1285 under

Butigeidis

Butigeidis (''Budikid''; be, Будзікід) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1285 to 1290/1291, assuming power after the death of Daumantas. He is the first known and undisputed member of the Gediminids.

He started his rule when the Li ...

.

Vytenis (r. 1295–1315) and

Gediminas (r. 1315–1341), after whom the

Gediminid dynasty is named, had to deal with constant raids and incursions from the Teutonic orders that were costly to repulse. Vytenis fought them effectively around 1298 and at about the same time was able to ally Lithuania with the German burghers of

Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the ...

. For their part, the Prussian Knights instigated a rebellion in Samogitia against the Lithuanian ruler in 1299–1300, followed by twenty incursions there in 1300–15.

Gediminas also fought the Teutonic Knights, and besides that made shrewd diplomatic moves by cooperating with the government of Riga in 1322–23 and taking advantage of the conflict between the Knights and Archbishop Friedrich von Pernstein of Riga.

Gediminas expanded Lithuania's international connections by conducting correspondence with Pope

John XXII as well as with rulers and other centers of power in Western Europe, and he invited German colonists to settle in Lithuania.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 34–35] Responding to Gediminas' complaints about the aggression from the Teutonic Order, the pope forced the Knights to observe a four-year peace with Lithuania in 1324–1327.

Opportunities for the Christianization of Lithuania were investigated by the pope's legates, but they met with no success.

From the time of Mindaugas, the country's rulers attempted to break Lithuania's cultural isolation, join

Western Christendom and thus be protected from the Knights, but the Knights and other interests had been able to block the process.

In the 14th century, Gediminas' attempts to become baptized (1323–1324) and establish Catholic Christianity in his country were thwarted by the Samogitians and Gediminas' Orthodox courtiers.

In 1325,

Casimir, the son of the Polish king

Władysław I, married Gediminas' daughter

Aldona

Aldona is a village in the Taluka of Bardez in the Indian state of Goa. It is known for producing several prominent Goans.

Geography

Aldona is located at at an average elevation of .

Aldona, as a comunidade-village, comprises around 16 w ...

, who became queen of Poland when Casimir ascended the Polish throne in 1333. The marriage confirmed the prestige of the Lithuanian state under Gediminas, and a defensive alliance with Poland was concluded the same year. Yearly incursions of the Knights resumed in 1328–1340, to which the Lithuanians responded with raids into Prussia and Latvia.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 53–55]

The reign of Grand Duke Gediminas constituted the first period in Lithuanian history in which the country was recognized as a great power, mainly due to the extent of its territorial expansion into Ruthenia.

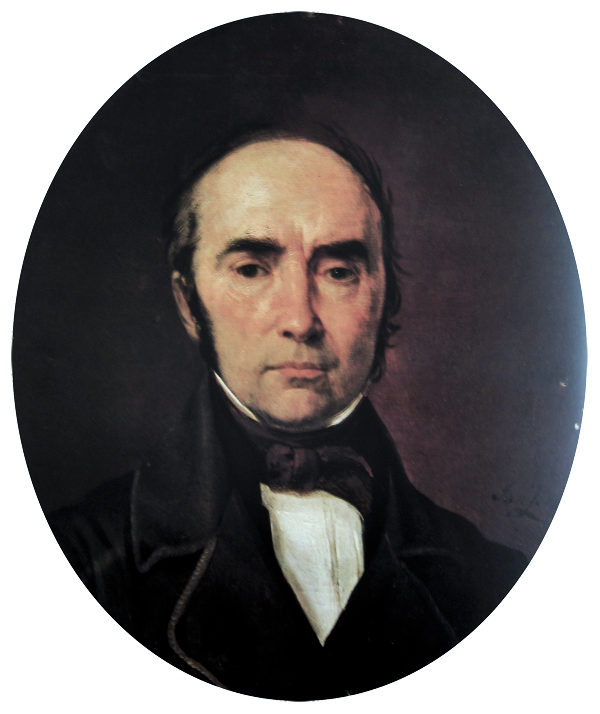

Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor a ...

, '' Europe: A History'', p. 392, 1998 New York, HarperPerennial, Lithuania was unique in Europe as a pagan-ruled "kingdom" and fast-growing military power suspended between the worlds of

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

Christianity. To be able to afford the extremely costly defense against the Teutonic Knights, it had to expand to the east. Gediminas accomplished Lithuania's eastern expansion by challenging the

Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, who from the 1230s sponsored a

Mongol invasion of Rus'

The Mongol Empire invaded and conquered Kievan Rus' in the 13th century, destroying numerous southern cities, including the largest cities, Kiev (50,000 inhabitants) and Chernihiv (30,000 inhabitants), with the only major cities escaping de ...

.

[''A Concise History of Poland'', by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki. Cambridge: ]Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

, 2nd edition 2006, , pp. 38–39 The collapse of the political structure of

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

created a partial regional power vacuum that Lithuania was able to exploit.

Through alliances and conquest, in competition with the

Principality of Moscow,

the Lithuanians eventually gained control of vast expanses of the western and southern portions of the former Kievan Rus'.

Gediminas' conquests included the western

Smolensk region, southern

Polesia

Polesia, Polesie, or Polesye, uk, Полісся (Polissia), pl, Polesie, russian: Полесье (Polesye) is a natural and historical region that starts from the farthest edge of Central Europe and encompasses Eastern Europe, including East ...

and (temporarily)

Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, which was ruled around 1330 by Gediminas' brother

Fiodor.

The Lithuanian-controlled area of Ruthenia grew to include most of modern

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

and

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

(the

Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

basin) and comprised a massive state that stretched from the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

to the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

in the 14th and 15th centuries.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 37–39]

In the 14th century, many Lithuanian princes installed to govern the Ruthenia lands accepted

Eastern Christianity

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent an ...

and assumed Ruthenian custom and names in order to appeal to the culture of their subjects. Through this means, integration into the Lithuanian state structure was accomplished without disturbing local ways of life.

The Ruthenian territories acquired were vastly larger, more densely populated and more highly developed in terms of church organization and literacy than the territories of core Lithuania. Thus the Lithuanian state was able to function because of the contributions of the

Ruthenian culture representatives.

Historical territories of the former Ruthenian dukedoms were preserved under the Lithuanian rule, and the further they were from Vilnius, the more autonomous the localities tended to be.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 41] Lithuanian soldiers and Ruthenians together defended Ruthenian strongholds, at times paying tribute to the

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmen ...

for some of the outlying localities.

Ruthenian lands may have been ruled jointly by Lithuania and the Golden Horde as

condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

s until the time of

Vytautas

Vytautas (c. 135027 October 1430), also known as Vytautas the Great ( Lithuanian: ', be, Вітаўт, ''Vitaŭt'', pl, Witold Kiejstutowicz, ''Witold Aleksander'' or ''Witold Wielki'' Ruthenian: ''Vitovt'', Latin: ''Alexander Vitoldus'', O ...

, who stopped paying tribute.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), p. 40] Gediminas' state provided a counterbalance against the influence of Moscow and enjoyed good relations with the Ruthenian principalities of

Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=pskov-ru.ogg, p=pskof; see also names in other languages) is a city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, located about east of the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population ...

,

Veliky Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

and

Tver

Tver ( rus, Тверь, p=tvʲerʲ) is a city and the administrative centre of Tver Oblast, Russia. It is northwest of Moscow. Population:

Tver was formerly the capital of a powerful medieval state and a model provincial town in the Russi ...

. Direct military confrontations with the Principality of Moscow under

Ivan I occurred around 1335.

Algirdas and Kęstutis

Around 1318, Gediminas' elder son

Algirdas

Algirdas ( be, Альгерд, Alhierd, uk, Ольгерд, Ольґерд, Olherd, Olgerd, pl, Olgierd; – May 1377) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania. He ruled the Lithuanians and Ruthenians from 1345 to 1377. With the help of his br ...

married

Maria of Vitebsk Maria of Vitebsk (died before 1349) was the first wife of Algirdas, future Grand Duke of Lithuania (marriage took place around 1318). Very little is known about her life. The only child of a Russian prince Yaroslav, Maria was the only heir to the P ...

, the daughter of Prince Yaroslav of

Vitebsk, and settled in

Vitebsk to rule the principality.

Of Gediminas' seven sons, four remained pagan and three converted to Orthodox Christianity.

Upon his death, Gediminas divided his domains among the seven sons, but Lithuania's precarious military situation, especially on the Teutonic frontier, forced the brothers to keep the country together.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 55–56] From 1345, Algirdas took over as the Grand Duke of Lithuania. In practice, he ruled over Lithuanian Ruthenia only, whereas

Lithuania proper was the domain of his equally able brother

Kęstutis. Algirdas fought the Golden Horde Tatars and the Principality of Moscow; Kęstutis took upon himself the demanding struggle with the Teutonic Order.

The warfare with the Teutonic Order continued from 1345, and in 1348, the Knights defeated the Lithuanians at the

Battle of Strėva. Kęstutis requested King

Casimir of Poland to mediate with the pope in hopes of converting Lithuania to Christianity, but the result was negative, and Poland took from Lithuania in 1349 the

Halych area and some Ruthenian lands further north. Lithuania's situation improved from 1350, when Algirdas formed an alliance with the

Principality of Tver. Halych was ceded by Lithuania, which brought peace with Poland in 1352. Secured by those alliances, Algirdas and Kęstutis embarked on the implementation of policies to expand Lithuania's territories further.

Bryansk

Bryansk ( rus, Брянск, p=brʲansk) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Bryansk Oblast, Russia, situated on the Desna (river), River Desna, southwest of Moscow. Population:

Geography Urban la ...

was taken in 1359, and in 1362, Algirdas captured Kyiv after defeating the Mongols at the

Battle of Blue Waters

The Battle of Blue Waters ( lt, Mūšis prie Mėlynųjų Vandenų, be, Бітва на Сініх Водах, uk, Битва на Синіх Водах) was a battle fought at some time in autumn 1362 or 1363 on the banks of the Syniukha river, ...

.

Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

,

Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-centra ...

and

left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine ( uk, Лівобережна Україна, translit=Livoberezhna Ukrayina; russian: Левобережная Украина, translit=Levoberezhnaya Ukraina; pl, Lewobrzeżna Ukraina) is a historic name of the part of Ukrain ...

were also incorporated. Kęstutis heroically fought for the survival of ethnic Lithuanians by attempting to repel about thirty incursions by the Teutonic Knights and their European guest fighters.

Kęstutis also attacked the Teutonic possessions in Prussia on numerous occasions, but the Knights took

Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Traka ...

in 1362.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 56–58] The dispute with Poland renewed itself and was settled by the peace of 1366, when Lithuania gave up a part of Volhynia including

Volodymyr. A peace with the Livonian Knights was also accomplished in 1367. In 1368, 1370 and 1372, Algirdas invaded the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

and each time approached

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

itself. An "eternal" peace (the

Treaty of Lyubutsk) was concluded after the last attempt, and it was much needed by Lithuania due to its involvement in heavy fighting with the Knights again in 1373–1377.

The two brothers and Gediminas' other offspring left many ambitious sons with inherited territory. Their rivalry weakened the country in the face of the Teutonic expansion and the newly assertive Grand Duchy of Moscow, buoyed by the 1380 victory over the Golden Horde at the

Battle of Kulikovo

The Battle of Kulikovo (russian: Мамаево побоище, Донское побоище, Куликовская битва, битва на Куликовом поле) was fought between the armies of the Golden Horde, under the command ...

and intent on the unification of all Rus' lands under its rule.

Jogaila's conflict with Kęstutis, Vytautas

Algirdas died in 1377, and his son

Jogaila became grand duke while Kęstutis was still alive. The Teutonic pressure was at its peak, and Jogaila was inclined to cease defending Samogitia in order to concentrate on preserving the Ruthenian empire of Lithuania. The Knights exploited the differences between Jogaila and Kęstutis and procured a separate armistice with the older duke in 1379. Jogaila then made overtures to the Teutonic Order and concluded the secret

Treaty of Dovydiškės with them in 1380, contrary to Kęstutis' principles and interests. Kęstutis felt he could no longer support his nephew and in 1381, when Jogaila's forces were preoccupied with quenching a rebellion in

Polotsk, he entered Vilnius in order to remove Jogaila from the throne. A

Lithuanian civil war ensued. Kęstutis' two raids against Teutonic possessions in 1382 brought back the tradition of his past exploits, but Jogaila retook Vilnius during his uncle's absence. Kęstutis was captured and died in Jogaila's custody. Kęstutis' son

Vytautas

Vytautas (c. 135027 October 1430), also known as Vytautas the Great ( Lithuanian: ', be, Вітаўт, ''Vitaŭt'', pl, Witold Kiejstutowicz, ''Witold Aleksander'' or ''Witold Wielki'' Ruthenian: ''Vitovt'', Latin: ''Alexander Vitoldus'', O ...

escaped.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 58–60]

Jogaila agreed to the

Treaty of Dubysa

The Treaty of Dubysa or Treaty of Dubissa ( lt, Dubysos sutartys) consisted of three legal acts formulated on 31 October 1382 between Jogaila, Grand Duke of Lithuania, with his brother Skirgaila and Konrad von Wallenrode, Marshal of the Teutonic ...

with the Order in 1382, an indication of his weakness. A four-year truce stipulated Jogaila's conversion to Catholicism and the cession of half of Samogitia to the Teutonic Knights. Vytautas went to Prussia in seek of the support of the Knights for his claims, including the

Duchy of Trakai, which he considered inherited from his father. Jogaila's refusal to submit to the demands of his cousin and the Knights resulted in their joint invasion of Lithuania in 1383. Vytautas, however, having failed to gain the entire duchy, established contacts with the grand duke. Upon receiving from him the areas of

Grodno

Grodno (russian: Гродно, pl, Grodno; lt, Gardinas) or Hrodna ( be, Гродна ), is a city in western Belarus. The city is located on the Neman River, 300 km (186 mi) from Minsk, about 15 km (9 mi) from the Polish b ...

,

Podlasie

Podlachia, or Podlasie, ( pl, Podlasie, , be, Падляшша, translit=Padliašša, uk, Підляшшя, translit=Pidliashshia) is a historical region in the north-eastern part of Poland. Between 1513 and 1795 it was a voivodeship with the c ...

and

Brest, Vytautas switched sides in 1384 and destroyed the border strongholds entrusted to him by the Order. In 1384, the two Lithuanian dukes, acting together, waged a successful expedition against the lands ruled by the Order.

By that time, for the sake of its long-term survival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had initiated the processes leading to its imminent acceptance of European

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

.

The Teutonic Knights aimed at a territorial unification of their Prussian and Livonian branches by conquering Samogitia and all of Lithuania proper, following the earlier subordination of the Prussian and Latvian tribes. To dominate the neighboring Baltic and Slavic people and expand into a great Baltic power, the Knights used German and other volunteer fighters. They unleashed 96 onslaughts in Lithuania during the period 1345–1382, against which the Lithuanians were able to respond with only 42 retributive raids of their own. Lithuania's Ruthenian empire in the east was also threatened by both the unification of Rus' ambitions of Moscow and the centrifugal activities pursued by the rulers of some of the more distant provinces.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 70–74]

13th–14th century Lithuanian society

The Lithuanian state of the later 14th century was primarily binational, Lithuanian and Ruthenian (in territories that correspond to the modern Belarus and Ukraine). Of its 800,000 square kilometers total area, 10% comprised ethnic Lithuania, probably populated by no more than 300,000 inhabitants. Lithuania was dependent for its survival on the human and material resources of the Ruthenian lands.

[Ochmański (1982), p. 60]

The increasingly differentiated Lithuanian society was led by princes of the

Gediminid

The House of Gediminid or simply the Gediminids ( lt, Gediminaičiai, sgs, Gedėmėnātē, be, Гедзімінавічы, pl, Giedyminowicze, uk, Гедиміновичі;) were a dynasty of monarchs in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that rei ...

and

Rurik

Rurik (also Ryurik; orv, Рюрикъ, Rjurikŭ, from Old Norse '' Hrøríkʀ''; russian: Рюрик; died 879); be, Рурык, Ruryk was a semi-legendary Varangian chieftain of the Rus' who in the year 862 was invited to reign in Novgor ...

dynasties and the descendants of former ''kunigas'' chiefs from families such as the

Giedraitis,

Olshanski Olshanski or Olshansky is a Ukrainian or Belorussian habitational name for someone from Olshana or Olshanka in Ukraine or Olshany in Belarus or a americanized form of Polish and Jewish (from Poland) Olszanski. Notable people with the name include:

...

and Svirski. Below them in rank was the regular

Lithuanian nobility (or

boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

s), in Lithuania proper strictly subjected to the princes and generally living on modest family farms, each tended by a few feudal subjects or, more often, slave workers if the boyar could afford them. For their military and administrative services, Lithuanian boyars were compensated by exemptions from public contributions, payments, and Ruthenian land grants. The majority of the ordinary rural workers were free. They were obligated to provide crafts and numerous contributions and services; for not paying these types of debts (or for other offences), one could be forced into slavery.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 60–62]

The Ruthenian princes were Orthodox, and many Lithuanian princes also converted to

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonic ...

, even some who resided in Lithuania proper, or at least their wives. The masonry Ruthenian churches and monasteries housed learned monks, their writings (including

Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

translations such as the

Ostromir Gospels) and collections of religious art. A Ruthenian quarter populated by Lithuania's Orthodox subjects, and containing their church, existed in Vilnius from the 14th century. The grand dukes' chancery in Vilnius was staffed by Orthodox churchmen, who, trained in the

Church Slavonic language

Church Slavonic (, , literally "Church-Slavonic language"), also known as Church Slavic, New Church Slavonic or New Church Slavic, is the conservative Slavic liturgical language used by the Eastern Orthodox Church in Belarus, Bosnia and Her ...

, developed

Chancery Slavonic, a Ruthenian written language useful for official record keeping. The most important of the Grand Duchy's documents, the

Lithuanian Metrica

The Lithuanian Metrica or the Metrica of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ( la, Acta Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae, lt, Lietuvos Metrika, pl, Metryka Litewska, or ''Metryka Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego''; be, Літоўская Метрыка, uk, ...

, the

Lithuanian Chronicles The Lithuanian Chronicles ( lt, Lietuvos metraščiai, also called Belarusian-Lithuanian Chronicles) are three redactions of chronicles compiled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. All redactions were written in the Ruthenian language and served the ...

and the

Statutes of Lithuania, were all written in that language.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 41–44]

German,

Jewish and

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

n settlers were invited to live in Lithuania; the last two groups established their own denominational communities directly under the ruling dukes. The Tatars and

Crimean Karaites were entrusted as soldiers for the dukes' personal guard.

Towns developed to a much lesser degree than in nearby Prussia or

Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

. Outside of Ruthenia, the only cities were

Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

(Gediminas' capital from 1323), the old capital of

Trakai

Trakai (; see names section for alternative and historic names) is a historic town and lake resort in Lithuania. It lies west of Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Because of its proximity to Vilnius, Trakai is a popular tourist destination. ...

and

Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Traka ...

.

and

Kreva

Kreva ( be, Крэва, ; lt, Krėva or Krẽvas; pl, Krewo; russian: Крéво) is a township in the Smarhon District of Grodno Region, Belarus. The first mention dates to the 13th century. The toponym is derived from the name of the Kriv ...

were the other old political centers.

Vilnius in the 14th century was a major social, cultural and trading center. It linked economically central and eastern Europe with the

Baltic area. Vilnius merchants enjoyed privileges that allowed them to trade over most of the territories of the Lithuanian state. Of the passing Ruthenian, Polish and German merchants (many from Riga), many settled in Vilnius and some built masonry residencies. The city was ruled by a governor named by the grand duke and its system of fortifications included three castles. Foreign currencies and Lithuanian currency (from the 13th century) were widely used.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 62–63]

The Lithuanian state maintained a

patrimonial power structure. Gediminid rule was hereditary, but the ruler would choose the son he considered most able to be his successor. Councils existed, but could only advise the duke. The huge state was divided into a hierarchy of territorial units administered by designated officials who were also empowered in judicial and military matters.

The Lithuanians spoke in a number of Aukštaitian and Samogitian (West-Baltic) dialects. But the tribal peculiarities were disappearing and the increasing use of the name ''Lietuva'' was a testimony to the developing Lithuanian sense of separate identity. The forming Lithuanian

feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

preserved many aspects of the earlier societal organization, such as the family clan structure, free peasantry and some slavery. The land belonged now to the ruler and the nobility. Patterns imported primarily from Ruthenia were used for the organization of the state and its structure of power.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 68–69]

Following the establishment of

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholi ...

at the end of the 14th century, the occurrence of pagan

cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a Cadaver, dead body through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India ...

burial ceremonies markedly decreased.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 44–47]

Dynastic union with Poland, Christianization of the state

Jogaila's Catholic conversion and rule

As the power of the Lithuanian warlord dukes expanded to the south and east, the cultivated

East Slavic Ruthenians exerted influence on the Lithuanian ruling class.

[Snyder (2003), pp. 17–18] They brought with them the

Church Slavonic

Church Slavonic (, , literally "Church-Slavonic language"), also known as Church Slavic, New Church Slavonic or New Church Slavic, is the conservative Slavic liturgical language used by the Eastern Orthodox Church in Belarus, Bosnia and Her ...

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

of the

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

Christian religion, a written language (Chancery Slavonic) that was developed to serve the Lithuanian court's document-producing needs for a few centuries, and a system of laws. By these means, Ruthenians transformed

Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

into a major center of Kievan Rus' civilization.

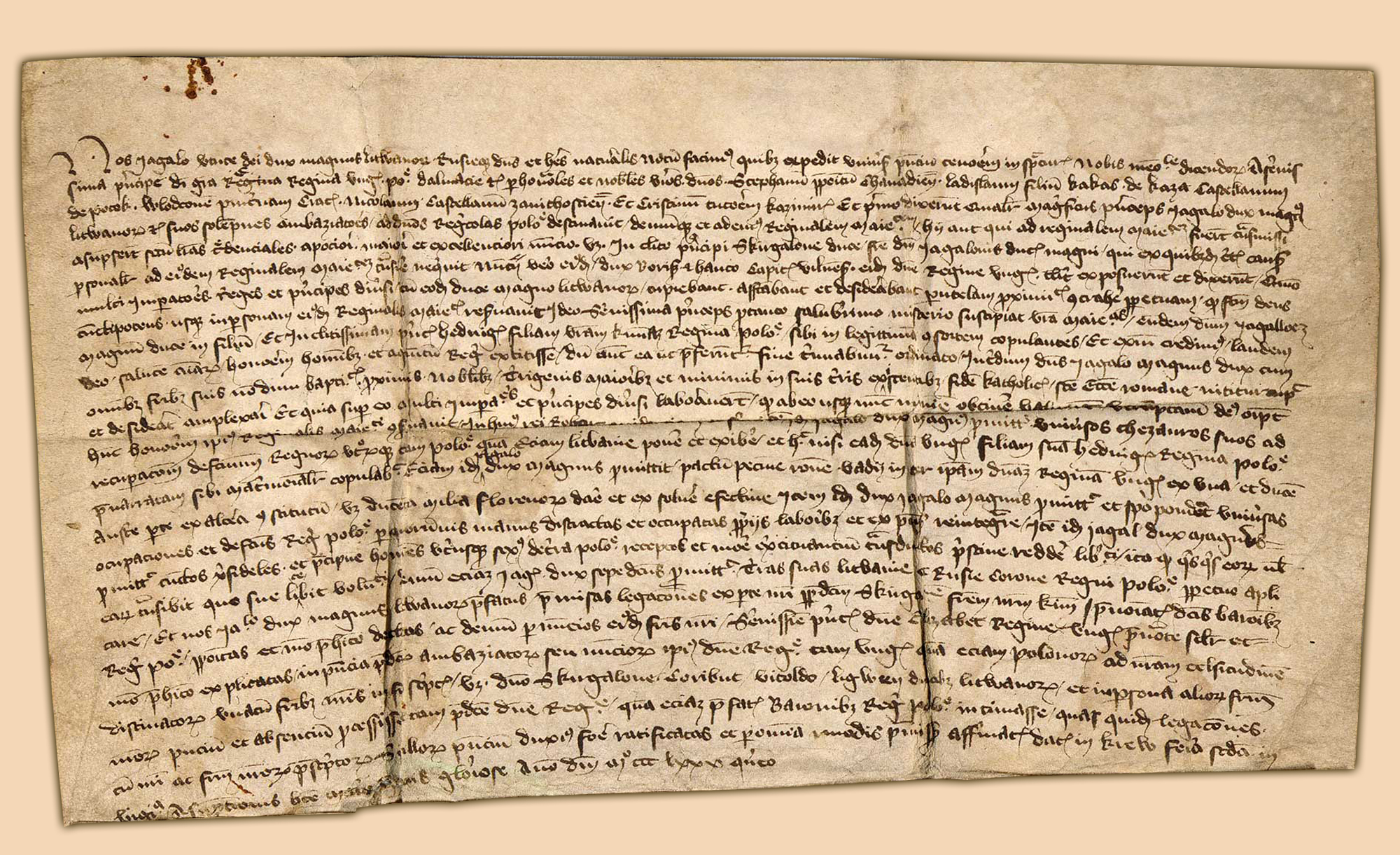

By the time of Jogaila's acceptance of Catholicism at the

Union of Krewo in 1385, many institutions in his realm and members of his family had been to a large extent assimilated already into the Orthodox Christianity and became Russified (in part a result of the deliberate policy of the Gediminid ruling house).

Catholic influence and contacts, including those derived from German settlers, traders and missionaries from Riga,

[Ochmański (1982), p. 67] had been increasing for some time around the northwest region of the empire, known as Lithuania proper. The

Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

and

Dominican friar orders existed in Vilnius from the time of

Gediminas.

Kęstutis in 1349 and

Algirdas

Algirdas ( be, Альгерд, Alhierd, uk, Ольгерд, Ольґерд, Olherd, Olgerd, pl, Olgierd; – May 1377) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania. He ruled the Lithuanians and Ruthenians from 1345 to 1377. With the help of his br ...

in 1358 negotiated Christianization with the pope, the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

and the Polish king. The

Christianization of Lithuania thus involved both Catholic and Orthodox aspects. Conversion by force as practiced by the

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

had actually been an impediment that delayed the progress of Western Christianity in the grand duchy.

, a grand duke since 1377, was himself still a pagan at the start of his reign. In 1386, agreed to the offer of the Polish crown by leading Polish nobles, who were eager to take advantage of Lithuania's expansion, if he become a Catholic and married the 13-year-old crowned king (not queen)

Jadwiga

Jadwiga (; diminutives: ''Jadzia'' , ''Iga'') is a Polish feminine given name. It originated from the old German feminine given name ''Hedwig'' (variants of which include ''Hedwiga''), which is compounded from ''hadu'', "battle", and ''wig'', "figh ...

.

[Lukowski & Zawadzki (2001), p. 37] For the near future, Poland gave Lithuania a valuable ally against increasing threats from the Teutonic Knights and the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

. Lithuania, in which Ruthenians outnumbered ethnic Lithuanians by several times, could ally with either the Grand Duchy of Moscow or Poland. A Russian deal was also negotiated with

Dmitry Donskoy

Saint Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy ( rus, Дми́трий Ива́нович Донско́й, Dmítriy Ivanovich Donskóy, also known as Dimitrii or Demetrius), or Dmitry of the Don, sometimes referred to simply as Dmitry (12 October 1350 – 1 ...

in 1383–1384, but Moscow was too distant to be able to assist with the problems posed by the Teutonic orders and presented a difficulty as a center competing for the loyalty of the Orthodox Lithuanian Ruthenians.

[Lukowski & Zawadzki (2001), pp. 38–40]

Jogaila was baptized, given the baptismal name Władysław, married Queen Jadwiga, and was crowned

King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

in February 1386.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 74–76][Krzysztof Baczkowski – ''Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506)'' (History of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506)), pp. 61–68]

Jogaila's baptism and crowning were followed by the final and official

Christianization of Lithuania.

[Lukowski & Zawadzki (2001), pp. 38–42] In the fall of 1386, the king returned to Lithuania and the next spring and summer participated in mass conversion and baptism ceremonies for the general population.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 76–78] The establishment of a bishopric in Vilnius in 1387 was accompanied by Jogaila's extraordinarily generous endowment of land and peasants to the Church and exemption from state obligations and control. This instantly transformed the Lithuanian Church into the most powerful institution in the country (and future grand dukes lavished even more wealth on it). Lithuanian boyars who accepted baptism were rewarded with a more limited privilege improving their legal rights.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 78–79][Krzysztof Baczkowski – ''Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506)'' (History of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506)), pp. 68–74] Vilnius' townspeople were granted self-government. The Church proceeded with its civilizing mission of literacy and education, and the

estates of the realm

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed a ...

started to emerge with their own separate identities.

Jogaila's orders for his court and followers to convert to Catholicism were meant to deprive the Teutonic Knights of the justification for their practice of forced conversion through military onslaughts. In 1403 the pope prohibited the Order from conducting warfare against Lithuania, and its threat to Lithuania's existence (which had endured for two centuries) was indeed neutralized. In the short term, Jogaila needed Polish support in his struggle with his cousin Vytautas.

Lithuania at its peak under Vytautas

The

Lithuanian Civil War of 1389–1392 involved the Teutonic Knights, the Poles, and the competing factions loyal to Jogaila and

Vytautas

Vytautas (c. 135027 October 1430), also known as Vytautas the Great ( Lithuanian: ', be, Вітаўт, ''Vitaŭt'', pl, Witold Kiejstutowicz, ''Witold Aleksander'' or ''Witold Wielki'' Ruthenian: ''Vitovt'', Latin: ''Alexander Vitoldus'', O ...

in Lithuania. Amid ruthless warfare, the grand duchy was ravaged and threatened with collapse. Jogaila decided that the way out was to make amends and recognize the rights of Vytautas, whose original goal, now largely accomplished, was to recover the lands he considered his inheritance. After negotiations, Vytautas ended up gaining far more than that; from 1392 he became practically the ruler of Lithuania, a self-styled "Duke of Lithuania," under a compromise with Jogaila known as the

Ostrów Agreement. Technically, he was merely Jogaila's regent with extended authority. Jogaila realized that cooperating with his able cousin was preferable to attempting to govern (and defend) Lithuania directly from Kraków.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 79–80]

Vytautas had been frustrated by Jogaila's Polish arrangements and rejected the prospect of Lithuania's subordination to Poland.

Under Vytautas, a considerable centralization of the state took place, and the Catholicized

Lithuanian nobility became increasingly prominent in state politics.

The centralization efforts began in 1393–1395, when Vytautas appropriated their provinces from several powerful regional dukes in Ruthenia.

[Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 48–50] Several invasions of Lithuania by the Teutonic Knights occurred between 1392 and 1394, but they were repelled with the help of Polish forces. Afterwards, the Knights abandoned their goal of conquest of Lithuania proper and concentrated on subjugating and keeping Samogitia. In 1395,

Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia

Wenceslaus IV (also ''Wenceslas''; cs, Václav; german: Wenzel, nicknamed "the Idle"; 26 February 136116 August 1419), also known as Wenceslaus of Luxembourg, was King of Bohemia from 1378 until his death and King of Germany from 1376 until he ...

, the Order's formal superior, prohibited the Knights from raiding Lithuania.

In 1395, Vytautas conquered

Smolensk, and in 1397, he conducted a victorious expedition against a branch of the Golden Horde. Now he felt he could afford independence from Poland and in 1398 refused to pay the tribute due to Queen Jadwiga. Seeking freedom to pursue his internal and Ruthenian goals, Vytautas had to grant the Teutonic Order a large portion of Samogitia in the

Treaty of Salynas of 1398. The conquest of Samogitia by the Teutonic Order greatly improved its military position as well as that of the associated

Livonian Brothers of the Sword

The Livonian Brothers of the Sword ( la, Fratres militiæ Christi Livoniae, german: Schwertbrüderorden) was a Catholic military order established in 1202 during the Livonian Crusade by Albert, the third bishop of Riga (or possibly by Theoderi ...

. Vytautas soon pursued attempts to retake the territory, an undertaking for which needed the help of the Polish king.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 80–82]

During Vytautas' reign, Lithuania reached the peak of its territorial expansion, but his ambitious plans to subjugate all of Ruthenia were thwarted by his disastrous defeat in 1399 at the

Battle of the Vorskla River, inflicted by the Golden Horde. Vytautas survived by fleeing the battlefield with a small unit and realized the necessity of a permanent alliance with Poland.

[Lukowski & Zawadzki (2001), pp. 44–45]

The original Union of Krewo of 1385 was renewed and redefined on several occasions, but each time with little clarity due to the competing Polish and Lithuanian interests. Fresh arrangements were agreed to in the "

unions" of

Vilnius (1401),

Horodło (1413),

Grodno (1432) and

Vilnius (1499).

[Lukowski & Zawadzki (2001), pp. 41–42] In the Union of Vilnius, Jogaila granted Vytautas a lifetime rule over the grand duchy. In return, Jogaila preserved his formal supremacy, and Vytautas promised to "stand faithfully with the Crown and the King." Warfare with the Order resumed. In 1403,

Pope Boniface IX banned the Knights from attacking Lithuania, but in the same year Lithuania had to agree to the

Peace of Raciąż, which mandated the same conditions as in the Treaty of Salynas.

[Ochmański (1982), pp. 82–83]

Secure in the west, Vytautas turned his attention to the east once again. The campaigns fought between 1401 and 1408 involved Smolensk,

Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=pskov-ru.ogg, p=pskof; see also names in other languages) is a city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, located about east of the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population ...

, Moscow and

Veliky Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

. Smolensk was retained, Pskov and Veliki Novgorod ended up as Lithuanian dependencies, and a lasting territorial division between the Grand Duchy and Moscow was agreed in 1408 in the treaty of

Ugra, where a great battle failed to materialize.

[Krzysztof Baczkowski – ''Dzieje Polski późnośredniowiecznej (1370–1506)'' (History of Late Medieval Poland (1370–1506)), pp. 89–90]

The decisive war with the Teutonic Knights (the

Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

) was preceded in 1409 with a

Samogitian uprising supported by Vytautas. Ultimately the Lithuanian–Polish alliance was able to defeat the Knights at the

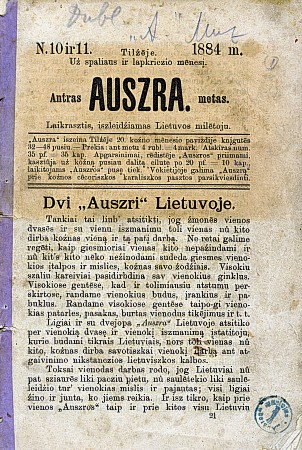

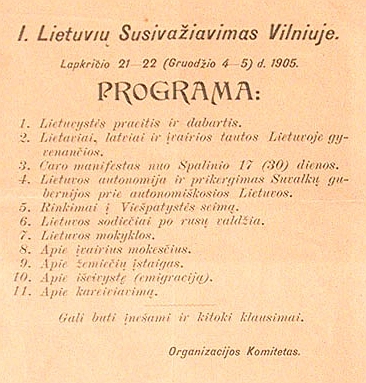

Battle of Grunwald