History of Corsica on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The prehistory of Corsica covers the long period from the

The prehistory of Corsica covers the long period from the

/ref> The first deposits of chipped stones and sculptural sketches found so far in Corsica, in the region of

After the fall of the

After the fall of the

In 1453 the people of Corsica held a general assembly, or Diet, at Lago Benedetto at which they voted to request the protection of the

In 1453 the people of Corsica held a general assembly, or Diet, at Lago Benedetto at which they voted to request the protection of the

A capable advocate of Corsican independence at last stepped forward from the ranks of Corsicans in exile in Italy,

A capable advocate of Corsican independence at last stepped forward from the ranks of Corsicans in exile in Italy,

After the French revolution, Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli, who had been exiled under the monarchy, became something of an idol of liberty and democracy. In 1789 he was invited to Paris by the National Constituent Assembly and was celebrated as a hero in front of the assembly. He was afterwards sent back to Corsica having been given the rank of lieutenant-general.

In 1795, after proclaiming the independence of Corsica, a constitution was adopted that made Corsica a kingdom in

After the French revolution, Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli, who had been exiled under the monarchy, became something of an idol of liberty and democracy. In 1789 he was invited to Paris by the National Constituent Assembly and was celebrated as a hero in front of the assembly. He was afterwards sent back to Corsica having been given the rank of lieutenant-general.

In 1795, after proclaiming the independence of Corsica, a constitution was adopted that made Corsica a kingdom in

In

In

After the Allied defeat of 1940, Corsica became part of the Southern zone of

After the Allied defeat of 1940, Corsica became part of the Southern zone of

In recent decades, Corsica has developed a thriving tourism industry, which has attracted a sizeable number of immigrants to the island in search of employment. Various movements, calling for either greater autonomy or complete independence from France, have been launched, some of whom have at times used violent means, like the National Front for the Liberation of Corsica (FLNC). In May 2001, the French government granted the island of Corsica limited autonomy, launching a process of

In recent decades, Corsica has developed a thriving tourism industry, which has attracted a sizeable number of immigrants to the island in search of employment. Various movements, calling for either greater autonomy or complete independence from France, have been launched, some of whom have at times used violent means, like the National Front for the Liberation of Corsica (FLNC). In May 2001, the French government granted the island of Corsica limited autonomy, launching a process of

online

* McLaren, Moray. "Pasquale Paoli: Hero of Corsica." ''History Today'' (Nov 1965) 15#11 pp 756–761. * Meeks, Joshua. "Revolutionary Corsica, 1789–1793." in ''France, Britain, and the Struggle for the Revolutionary Western Mediterranean'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2017) pp. 41–73. * Nicholas, Nick. "A history of the Greek colony of corsica." ''Journal of the Greek Diaspora'' 31 (2005): 33–78. covers 1600 to 1799

online

* * Savigear, Peter. "Intervention and the Balance of Power: An Eighteenth Century War of Liberation" ''Studies in History & Politics'' (1981) 2#2 pp 113–126, on Pasquale Paoli in 1768 * Varley, Karine. "Between Vichy France and fascist Italy: Redefining identity and the enemy in Corsica during the Second World War." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 47.3 (2012): 505-52

online

* Willis, F. Roy. "Development planning in eighteenth-century France: Corsica's Plan Terrier." ''French Historical Studies'' 11.3 (1980): 328–351

online

* Wilson, Stephen. ''Feuding, Conflict and Banditry in Nineteenth-Century Corsica'' (1988). 565pp.

Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

goes back to antiquity, and was known to Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, who described Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n habitation in the 6th century BCE. Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

and Carthaginians

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people, Semitic people who Phoenician settlement of North Africa, migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Iron ...

expelled the Ionian Greeks, and remained until the Romans arrived during the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

in 237 BCE. Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

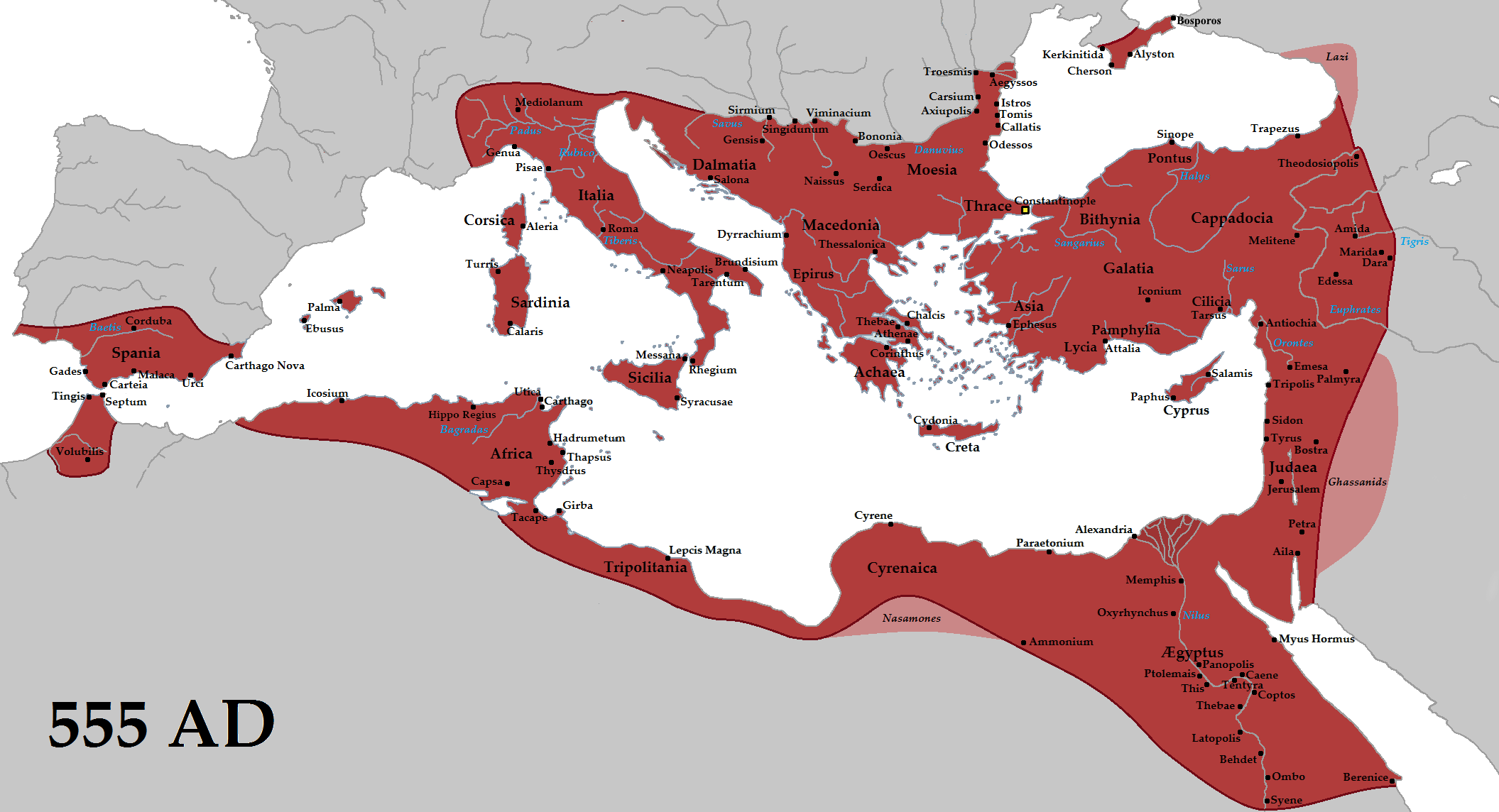

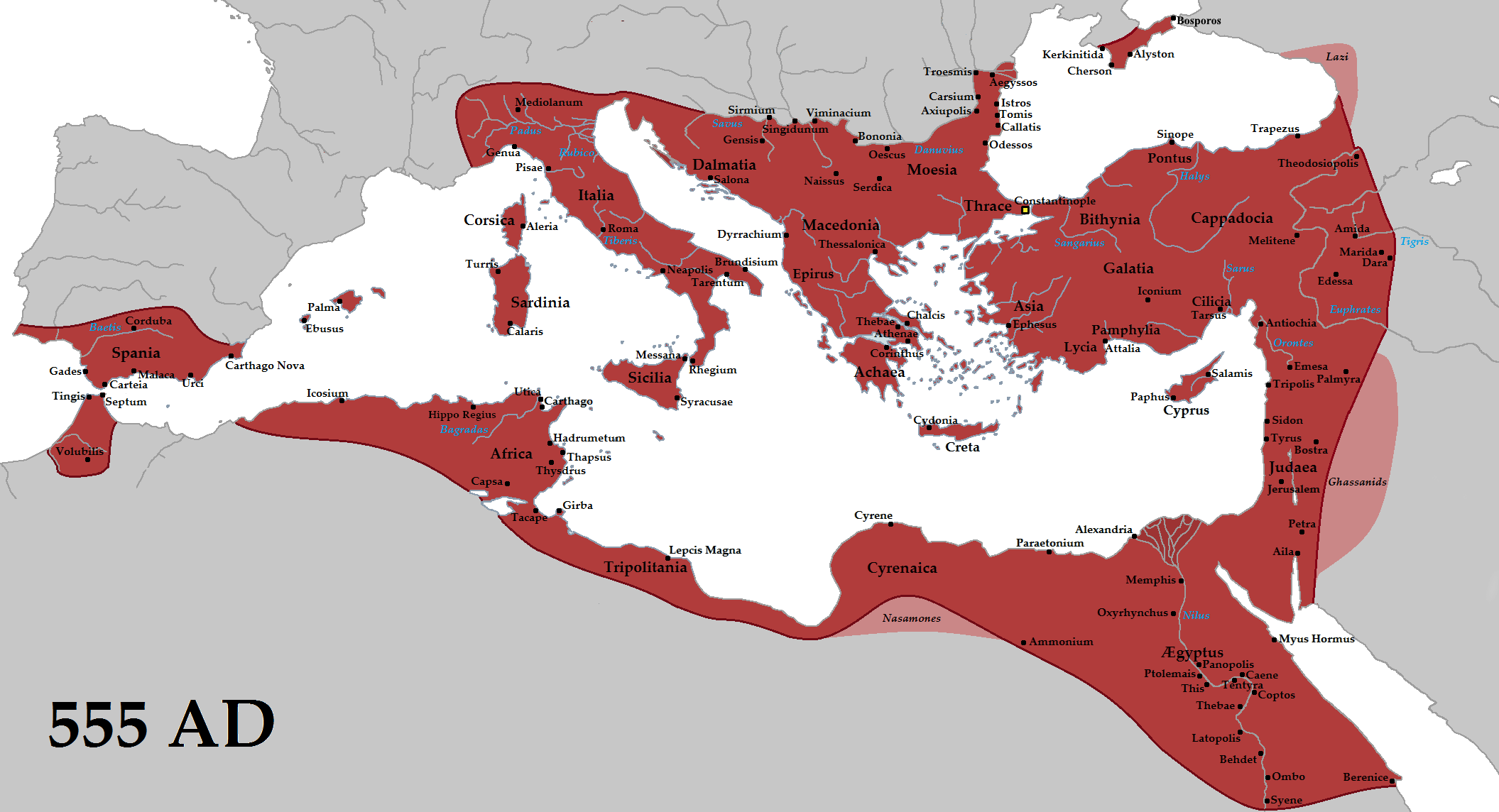

occupied it in 430 CE, followed by the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

a century later.

Raided by various Germanic and other groups for two centuries, it was conquered in 774 by Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

under the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, which fought for control against the Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century History of Germany, German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to ...

. After a period of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

anarchy, the island was transferred to the papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

, then to city states Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

and Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, which retained control over it for five centuries, until the establishment of the Corsican Republic

The Corsican Republic () was a short-lived state on the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea. It was proclaimed in July 1755 by Pasquale Paoli, who was seeking independence from the Republic of Genoa. Paoli created the Corsican Constitutio ...

in 1755. The French gained control in the 1768 Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

. Corsica was briefly independent as a Kingdom in union with Great Britain after the French Revolution in 1789, with a viceroy and elected Parliament, but returned to French rule in 1796.

Corsica strongly supported the allies in World War I, caring for wounded, and housing POWs. The poilus fought loyally and suffered great casualties. A recession after the war prompted a mass exodus to southern France. Wealthy Corsicans became colonizers in Algeria and Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia (historically known as Indochina and the Indochinese Peninsula) is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to th ...

.

After the Fall of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Net ...

in 1940, Corsica was part of the southern ''zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered b ...

'' of the Vichy regime

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against ...

. Fascist leader Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

agitated for Italian control, supported by Corsican irredentists. In 1942, Italy occupied Corsica with a huge force. German forces took over in 1943 after the Allied armistice with Italy. The Germans faced opposition from the French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

, retreating and evacuating the island by October 1943. Corsica then became an Allied air base, supporting the Mediterranean Theater in 1944, and the invasion of southern France in August 1944. Since the war, Corsica has developed a thriving tourism industry, and has been known for its independence movements, sometimes violent.

Geography

Corsica's strategic position in thewestern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

has significantly influenced its history. The island lies approximately 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) north of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

, separated by the Strait of Bonifacio

The Strait of Bonifacio (; ; ; ; ; ; ) is the strait between Corsica and Sardinia, named after the Corsican town Bonifacio. It is wide and divides the Tyrrhenian Sea from the western Mediterranean Sea. The strait is notorious among sailors for i ...

. It is about 50 kilometers (30 miles) west of the Isle of Elba, 80 kilometers (50 miles) from the coast of Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

, and approximately 170 kilometers (105 miles) from the French port of Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, following Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, Sardinia, and Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

.

Prehistory

The prehistory of Corsica covers the long period from the

The prehistory of Corsica covers the long period from the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories ...

to the first historical event, the founding of Aléria

Aléria (; Ancient Greek: /, ; Latin and Italian: ; ) is a commune in the Haute-Corse department of France on the island of Corsica, former bishopric and present Latin Catholic titular see. It includes the easternmost point in Metropolitan Fr ...

by the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

in 566 BCE.

During the Ice Ages, the average level of the Mediterranean Sea dropped and several natural bridges were created that allowed the passage of fauna from the Italian mainland to the Sardinian-Corsican archipelago, passing through the islands of the Tuscan archipelago and crossing at most a narrow stretch of sea. Around 12-14 000 years ago, the climate began the evolution that led it to its present form, and Corsica, detached from the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (, ; or ) , , , , is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenian people identified with the Etruscans of Italy.

Geography

The sea is bounded by the islands of C ...

, assumed its present-day island configuration. In the 19th century BCE, the hypothesis was developed that man may also have populated these lands by reaching them on foot when it was not yet completely an island; This thesis of Docteur Mattei was taken up by Count Colonna de Cesari Rocca, who noted how, at the time of his writing, anthropologists were becoming interested in the curious behavioural similarities between the characters of certain types of Corsican and Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

people. Pierre Paul Raoul Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, ''Histoire de la Corse'', Boyle, 1890 https://www.archive.org/download/histoiredelacors00colouoft/histoiredelacors00colouoft.pdf/ref> The first deposits of chipped stones and sculptural sketches found so far in Corsica, in the region of

Porto-Vecchio

Porto-Vecchio (, ; or ; , , or (South)) is a commune in the French department of Corse-du-Sud, on the island of Corsica.

Porto-Vecchio is a medium-sized port city placed on a good harbor, the southernmost of the marshy and alluvial east ...

, date back to around 9000 BC (Romanellian). A female skeleton ( la dame de Bonifacio) was found near the town of the same place.

The Early Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wi ...

is represented in Corsica by finds of cardinal pottery and imported obsidian. The major influences seem to come from both Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

and Sardinia.

In later phases, an important megalithic civilisation developed in Corsica, which left on the island dolmens

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (40003000 BCE) and w ...

(stazzòne, found near Cauria and Pagliagio), menhirs

A menhir (; from Brittonic languages: ''maen'' or ''men'', "stone" and ''hir'' or ''hîr'', "long"), standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large upright stone, emplaced in the ground by humans, typically dating from the European middle Bro ...

(stantare) and the original statues-menhirs, concentrated mainly in the south, at the site of Filitosa and that of Funtanaccia

Funtanaccia is an archaeological site in Corsica. It is located in the commune of Sartène.

In a distance of 300 m are the stone rows of Stantari

Stantari is an archaeology, archaeological site in Corsica. It is l ... and Rinaghju.

...

, near Sartene, but also present in the north, near San Fiorenzo

Saint-Florent (; , ; , ) is a commune in Haute-Corse department on the island of Corsica, France. Originally a fishing port located in the gulf of the same name, pleasure boats have now largely taken the place of fishing vessels.

Today, it is ...

. The site of Filitosa - a UNESCO World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

- is located near Sollacaro, towards the sea outlet of the Taravo Valley). According to the archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu

Giovanni Lilliu (13 March 1914 in Barumini, Italy – 19 February 2012 in Cagliari), was an archeologist, academician, publicist, politician and an expert of the Nuragic civilization. Largely due to his scientific and archeologic work in the Su ...

, in the second half of the 4th millennium B.C., Corsica was invested by a cultural current called the Culture of Arzachena, also known as the Corsican-Gallurese cultural facies, secondary to the cultural complex known as the Culture of Ozieri and extended over the whole of Sardinia.

The Corsican-Gallurese facies mainly affected the whole of Gallura

Gallura ( or ; ) is a region in North-Eastern Sardinia, Italy.

The name ''Gallùra'' is allegedly supposed to mean "stony area".

Geography

Gallùra has an area of . It is from the Italian peninsula and from the French island of Corsica.

...

with expansion beyond the Straits of Bonifacio into southern Corsica. According to G. Lilliu, this facies showed a society with an aristocratic and individualistic background, and was clearly distinguished from the predominant facies of Ozieri, which tended to be democratic and had clear influences from the eastern Mediterranean. The pastoral, aristocratic facies of Arzachena and the democratic agricultural culture of Ozieri constituted the most important sociological component of the pre-Nuragic Sardinian populations.

The Corsican Eneolithic

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vocalize it as st ...

is characterised by the Torrean civilization, which takes its name from the site of Terrina, on the central-eastern coast, where techniques related to copper metallurgy were widespread. In the Early Bronze Age, northern influences from the Polada culture

The Polada culture (22nd to 16th centuries BCE) is the name for a culture of the ancient Bronze Age which spread primarily in the territory of modern-day Lombardy, Veneto and Trentino, characterized by settlements on pile-dwellings.

The name der ...

are recorded on the island, as well as in Sardinia.

In this phase, the Torrean civilisation developed in the south. Numerous megalithic towers with a structure similar to that of the "Sardinian nuraghi" remain today from this culture. Due to the nature of the finds, their age and location, scholars have ascertained that this civilisation was an extension of the coeval civilisation that developed in Sardinia. According to an invasionist theory, mainly developed by Grosjean in the 1970s, the Torreani (whom the author makes out to be the ancient sea people of the Sherden

The Sherden (Egyptian: ''šrdn'', ''šꜣrdꜣnꜣ'' or ''šꜣrdynꜣ''; Ugaritic: ''šrdnn(m)'' and ''trtn(m)''; possibly Akkadian: ''šêrtânnu''; also glossed "Shardana" or "Sherdanu") are one of the several ethnic groups the Sea Peoples wer ...

) got the better of the megalithic people and drove them towards the centre and north of the island. However, this theory is no longer accepted by most scholars who see the Torreani as the evolution of the local Neoeneolithic communities. It was in this period that the people that the Greeks would call "Κὁρυιοι, Còrsi", also attested in Gallura and perhaps of Ligurian ancestry, as toponyms such as Asco and Venzolasca, with the typical suffix in ‘-asco’, would seem to suggest.

Classical antiquity

Name

The ancient Greeks, notablyHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, called the island ''Kurnos'' or ''Kyrnos'' (from ''kur'' or ''kyr'' meaning cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment of any length that hangs loosely and connects either at the neck or shoulders. They usually cover the back, shoulders, and arms. They come in a variety of styles and have been used th ...

); the name Corsica is Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and was in use in the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

.

Why Herodotus used Kyrnos and not some other name remains a mystery, and the phrases of the authors give no clue. The Roman historians, however, believed Corsa or Corsica (rightly or wrongly they interpreted -ica as an adjectival formative ending) was the native name of the island, but they could not give an explanation of its meaning. They did think that the natives were originally Ligures

The Ligures or Ligurians were an ancient people after whom Liguria, a region of present-day Northern Italy, north-western Italy, is named. Because of the strong Celts, Celtic influences on their language and culture, they were also known in anti ...

.

Iron Age and ancient history

Greek and Etruscan period

Beginning on the island around the 8th century BC, the Iron Age ended with Corsica's entry into history when the colony of Alalia was founded byIonian Greek

Ionic or Ionian Greek () was a subdialect of the Eastern or Attic Greek, Attic–Ionic Ancient Greek dialects, dialect group of Ancient Greek. The Ionic group traditionally comprises three dialectal varieties that were spoken in Euboea (West Ioni ...

colonists, the Phocians of Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, in 565 or 562 BC, near the site of the present-day town of Aleria. The Greeks called the island first Kalliste and later Cyrnos, Cernealis, Corsis and Cirné. Herodotus spoke of the Phocaeans, thus leaving the first documentary trace of the island, and narrated that after the foundation of Alalia other Phocaeans reached the island to escape the risk of being enslaved by the Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

.

In 535 B.C., following the battle of the Sardinian sea, they in turn were driven out by an Etruscan-Carthaginian coalition formed on the basis of a pact that had been drawn up for the purpose and which, after the conflict, provided for the division of the two islands over which influence had been won: Sardinia to the Carthaginians, Corsica to the Etruscans. In fact, according to Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, the Phocians had won, but it was a Cadmean victory, since of the 60 ships employed (half the total armament of the opposing fleets) 40 were sunk and the remainder rendered unserviceable. The Phocaeans then left Corsica and the Carthaginians and Etruscans were thus able to implement the partition pact equally. The Etruscans therefore resumed that control over the eastern shores of the island that they had previously consolidated with the activity of the warships of Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, Volterra

Volterra (; Latin: ''Volaterrae'') is a walled mountaintop town in the Tuscany region of Italy. Its history dates from before the 8th century BC and it has substantial structures from the Etruscan, Roman, and Medieval periods.

History

...

, Populonia

Populonia or Populonia Alta ( Etruscan: ''Pupluna'', ''Pufluna'' or ''Fufluna'', all pronounced ''Fufluna''; Latin: ''Populonium'', ''Populonia'', or ''Populonii'') today is a of the ''comune'' of Piombino (Tuscany, central Italy). As of 2009 its ...

, Tarquinia

Tarquinia (), formerly Corneto, is an old city in the province of Viterbo, Lazio, Central Italy, known chiefly for its ancient Etruscans, Etruscan tombs in the widespread necropolis, necropoleis, or cemeteries. Tarquinia was designated as a ...

and Cere

The beak, bill, or Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for pecking, wikt:grasp#Verb, grasping, and holding (in wikt:probe ...

. Their presence is attributed to the toponym Tarco on the south-eastern coast, which recalls the city of Tarquinia.This was followed by the incursions of the Siceliots from Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

, who founded a legendary Portus Syracusanus in the 5th century B.C., and again by the Carthaginians (4th century B.C.). The Syracusans first made a move towards the island under the command of Apello in 453 BC, but it was in 384 BC, under Dionysius I, that they launched their most important attack, since it was aimed not only at Corsica but also at the island of Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

and the Tuscan coast. The Portus Syracusanus has been classically identified at the site of today's Porto Vecchio, however there are several scholars from different periods who refute this thesis, arguing that it may have been in the Gulf of Santa Amanza, or in Bonifacio.

Roman era

Corsica came under Roman control in 238 BCE, during theFirst Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

, when Rome annexed both Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

from Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

, exploiting Carthage's internal struggles during the Mercenary War

The Mercenary War, also known as the Truceless War, was a mutiny by troops that were employed by Ancient Carthage, Carthage at the end of the First Punic War (264241 BC), supported by uprisings of African settlements revolting against C ...

. The islands were officially organized into the Roman province of Sardinia et Corsica in 227 BCE, marking one of Rome's earliest overseas provincial establishments. The Roman conquest faced significant resistance from the indigenous Corsican tribes, particularly in the island's rugged interior. Rebellions were frequent, with notable uprisings occurring in 231 BCE, which was suppressed by Gaius Papirius Maso, who celebrated a triumph on Mons Albanus.

Despite resistance, the Romans established several colonies to solidify their control. Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

founded Colonia Mariana in the northeast around 104 BCE, and Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

established Colonia Veneria Alaria at Aléria

Aléria (; Ancient Greek: /, ; Latin and Italian: ; ) is a commune in the Haute-Corse department of France on the island of Corsica, former bishopric and present Latin Catholic titular see. It includes the easternmost point in Metropolitan Fr ...

between 82 and 80 BCE. Aléria, originally a Phocaean Greek settlement known as Alalia, became a significant Roman city and naval base, with a population reaching approximately 20,000 at its peak. Roman infrastructure on Corsica was limited, with only one known major road running along the east coast from Piantarella through Aléria to Mariana. The Romans exploited the island's natural resources, including timber, iron, and salt, and introduced viticulture

Viticulture (, "vine-growing"), viniculture (, "wine-growing"), or winegrowing is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of ''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine ...

.

Under Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

's provincial reforms in 27 BCE, Sardinia et Corsica became a senatorial province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as governo ...

. In 6 CE, Corsica was separated into its own senatorial province, while Sardinia became an imperial province due to its strategic importance and the need for a substantial military presence. Corsica's administrative status fluctuated over time, alternating between senatorial and imperial control. The island remained relatively peaceful during the early Imperial period, with few significant events recorded. Notably, the philosopher Seneca was exiled to Corsica from 41 to 49 CE, during which time he wrote several works.

As the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

weakened, Corsica became vulnerable to external threats. In 430 CE, the Vandals

The Vandals are an American punk rock band, established in 1980 in Orange County, California. They have released ten full-length studio albums, three live albums, three live DVDs and have toured the world extensively, including performances on ...

, a Germanic tribe that had established a kingdom in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, conquered Corsica, integrating it into their maritime domain. In 534 CE, during the Vandalic War

The Vandalic War (533–534) was a conflict fought in North Africa between the forces of the Byzantine Empire (also known as the Eastern Roman Empire) and the Germanic Vandal Kingdom. It was the first war of Emperor Justinian I's , wherein the ...

, the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

under Emperor Justinian I launched a campaign to reclaim former Western Roman

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

territories. Corsica was recovered by Byzantine forces, restoring imperial control and introducing Eastern Roman (Byzantine) administrative and cultural influences to the island.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

, Corsica was frequented by migrant peoples and corsairs, notably Vandals, who plundered and ravaged at will until the coastal settlements fell into decline and the population occupied the slopes of the mountains. Rampant malaria in the coastal marshes reinforced this decision. Due largely to competition for the island from Ostrogothic

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

Foederati

''Foederati'' ( ; singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the '' socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign ...

who had settled on the Riviera

() is an Italian word which means , ultimately derived from Latin , through Ligurian . It came to be applied as a proper name to the coast of Liguria (the Genoa region in northwestern Italy) in the form , then shortened in English.

Riviera may a ...

, the Vandals never penetrated much beyond the coast, and their stay in Corsica was relatively short-lived, just long enough to prejudice the Corsicans against foreign adventurers on Corsican soil.

In 534, the armies of Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

recovered the island for the empire, but the Byzantines were not able to effectively defend the island from continuing raids by the Ostrogoths, the Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

, and the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

s. The Lombards, who had made themselves masters of the war- and famine-shattered Italian Peninsula, conquered the island in 725.

The Lombard supremacy on the island was short lived. In 774, the Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages, a group of Low Germanic languages also commonly referred to as "Frankish" varieties

* Francia, a post-Roman ...

king Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

conquered Corsica as he moved to subdue the Lombards and restore the Western Empire. For the next century and a half, the thus established Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

continually warred with the Saracens for control of the island. In 807, Charlemagne's constable Burchard defeated an invading force from Al Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

. In 930, Berengar II

Berengar II ( 900 – 4 August 966) was the king of Italy from 950 until his deposition in 961. He was a scion of the Anscarid and Unruoching dynasties, and was named after his maternal grandfather, Berengar I. He succeeded his father as ma ...

, King of Italy, invaded and subdued the imperial forces. Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), known as Otto the Great ( ) or Otto of Saxony ( ), was East Francia, East Frankish (Kingdom of Germany, German) king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the eldest son o ...

vanquished Berengar and restored Corsica to imperial control in 965.

Its external threats mostly vanquished, a period of feudal anarchy followed as local Corsican-based nobles warred on each other and struggled for control, culminating in the transfer of the island – at the request of its population – to the papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

in 1077. The Pope yielded civic administration to Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

in 1090, but contention between the Pisans and their rival Genoese soon engulfed Corsica. Repeated truces proved fleeting as the two naval and trading powers clashed for supremacy in the Western Mediterranean. The various Italian republics that arose began to assume responsibility for the security and prosperity of Corsica, starting with Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

, the closest. Corsica was finally removed from the fighting by annexation to the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

in 1217.

Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

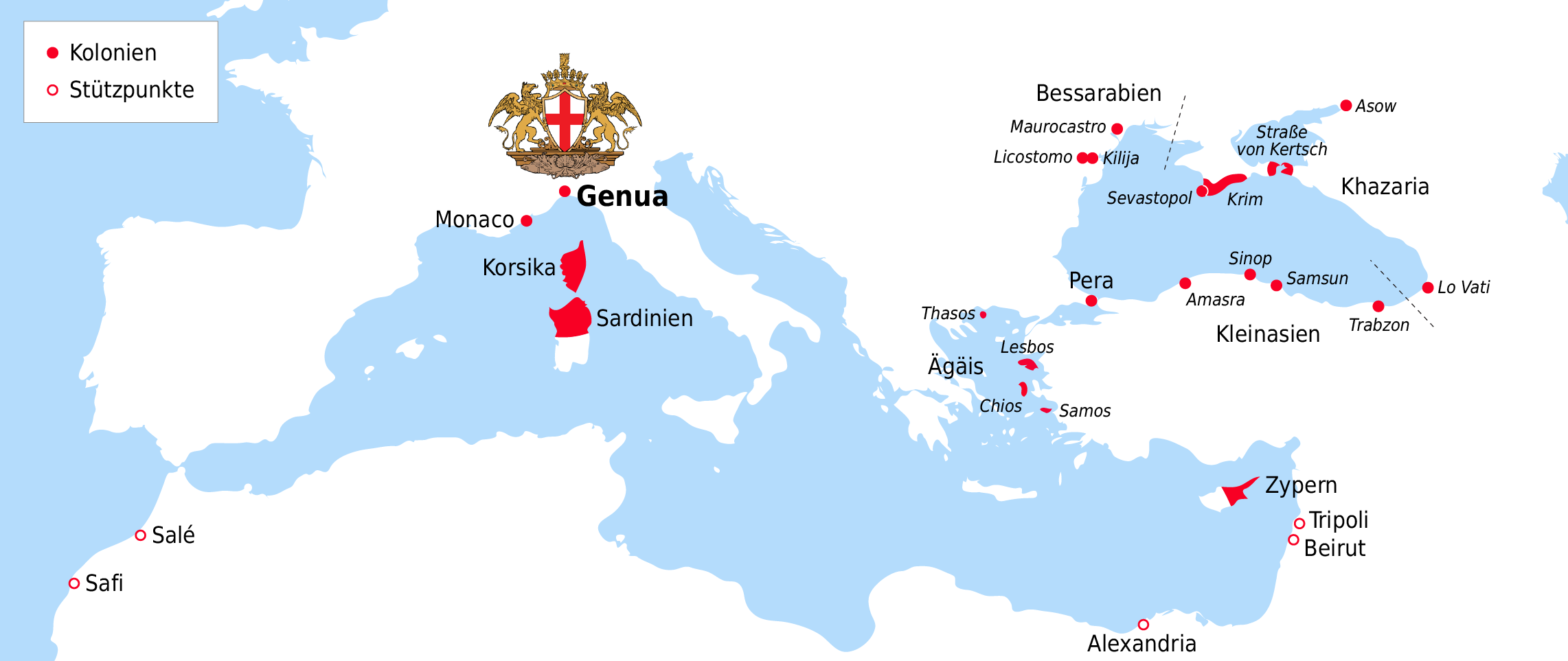

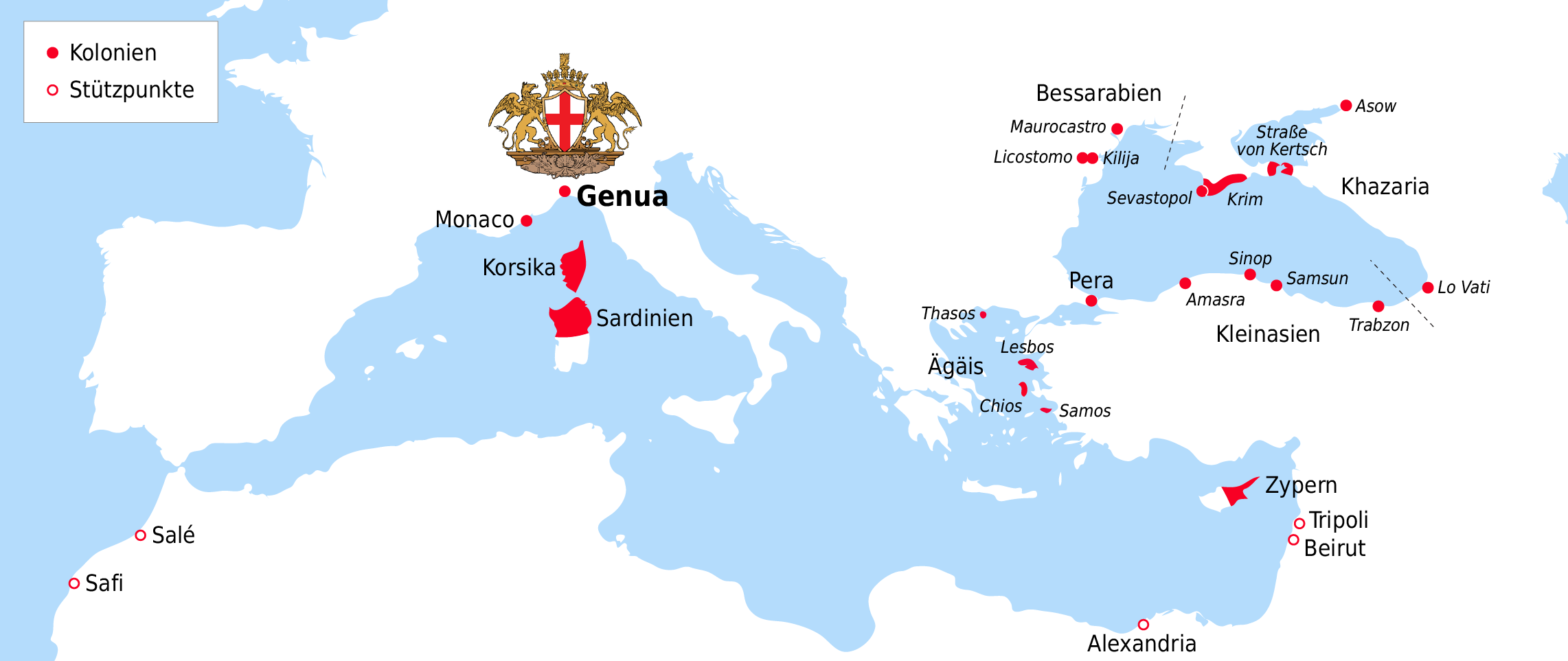

Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

retained control of the island during most of the Middle Ages but at the start of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

it fell to Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

in 1284, following the battle of Meloria against Pisa.

Corsica successively was part of the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

for five centuries. Despite take-overs by Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

between 1296 and 1434 and France between 1553 and 1559, Corsica would remain under Genoese control until the Corsican Republic

The Corsican Republic () was a short-lived state on the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea. It was proclaimed in July 1755 by Pasquale Paoli, who was seeking independence from the Republic of Genoa. Paoli created the Corsican Constitutio ...

of 1755 and under partial control until its purchase by France in 1768.

Bank of Saint George

However, the dissension and political conflict at home did not always permit Doges of Genoa to govern Corsica well or at all. During such periods the island was subject to destructive conflict between coalitions of signorial families. TheBank of Saint George

The Bank of Saint George ( or informally as ''Ufficio di San Giorgio'' or ''Banco'') was a financial institution of the Republic of Genoa. It was founded on 23 April 1407 to consolidate the public debt, which had been escalating due to the war ...

became involved as a major creditor

A creditor or lender is a party (e.g., person, organization, company, or government) that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some propert ...

of the Republic of Genoa. As security for their public loans they had obtained a franchise to collect public money; i.e., taxes.

Bank of Saint George

The Bank of Saint George ( or informally as ''Ufficio di San Giorgio'' or ''Banco'') was a financial institution of the Republic of Genoa. It was founded on 23 April 1407 to consolidate the public debt, which had been escalating due to the war ...

as a credible third-party. In return the bank would get the right to exercise their franchise in Corsica. This third-party solution became immediately popular. The government of Genoa placed Corsica in the bank's hands and the major contenders on Corsica agreed to a peace, some accepting cash payments for their cooperation.

Throughout the next century the bank undertook enterprises in the major coastal cities, sending in troops to secure the strong points, building or rebuilding the citadels, recruiting several hundred colonists per city, mainly Genoese, and constructing quarters for them within a city wall. Most of these "old cities" survive and are populated today, having served as the nucleus of modern Corsican coastal cities.

The natives were at first kept at bay. Typically more or less immediately but certainly by a few generations they were allowed to conurbate with the Genoese, especially as the latter were decimated by malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and required the assistance of the natives. Some conflict continued but within a few decades peace and order were restored to the island. Genoese watchtowers populated the entire coastline (and are there yet) where the forces of Genoese signori ruling from coastal castles kept a watchful eye for raiders, pirates, bandits and smugglers.

Sampiero Corso

Having begun its dominion in Corsica by building walled cities from which the Corsicans were to be excluded, theBank of Saint George

The Bank of Saint George ( or informally as ''Ufficio di San Giorgio'' or ''Banco'') was a financial institution of the Republic of Genoa. It was founded on 23 April 1407 to consolidate the public debt, which had been escalating due to the war ...

in the exercise of its taxation franchise finally became as unpopular in some quarters as the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

. It too generated a population of Corsican exiles, one of whom, Sampiero Corso, immigrated to France and became ultimately a high-ranking officer in the French army. He was thus on hand in Italy during the Italian War of 1551–1559

The Italian War of 1551–1559 began when Henry II of France declared war against Holy Roman Emperor Charles V with the intent of recapturing parts of Italy and ensuring French, rather than Habsburg, domination of European affairs. The war e ...

when the question came up in a conference of the general staff of what to do with Corsica, which was between France and Italy. At the insistence of Corso and other well-placed exiles the Marshal Paul de Termes gave orders, without the knowledge or assent of his commander, Henry II of France

Henry II (; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was List of French monarchs#House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589), King of France from 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I of France, Francis I and Claude of France, Claude, Du ...

, to take Corsica.

In August 1553, the Turkish fleet under Dragut

Dragut (; 1485 – 23 June 1565) was an Ottoman corsair, naval commander, governor, and noble. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extended across North Africa. Recognized for his military genius, and as being among "the ...

, an ally of the French under a Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between Francis I of France, Francis I, King of France and Suleiman the Magnificent, Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire. The strategic and s ...

, set sail transporting French troops to Cap Corse

Cap Corse (; , ; , ), a geographical area of Corsica, is a long peninsula located at the northern tip of the island. At the base of it is the second largest city in Corsica, Bastia. Cap Corse is also a Communauté de communes comprising 18 comm ...

in the Invasion of Corsica (1553)

The Invasion of Corsica of 1553 occurred when French, Ottoman, and Corsican exile forces combined to capture the island of Corsica from the Republic of Genoa.

The island had considerable strategic importance in the western Mediterranean, bein ...

. Bastia

Bastia ( , , , ; ) is a communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Haute-Corse, Corsica, France. It is located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It also has the second-highest popu ...

fell on the 24th, Saint-Florent on the 26th, Corte shortly after and Bonifacio in September. Before they could take Calvi the Turks went home in October for unknown reasons. Sampiero Corso proceeded to raise civil war in central Corsica, pitting signor against signor, wasting the villages of his opponents.

That November, Henry II opened negotiations with Genoa but too late. While parlaying the Genoese sent their best commander, Admiral Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

, with 15,000 men to Cap Corse, recapturing Saint-Florent in February 1554. By 1555, the French had been cleared from most of the coastal cities and Doria left. A Turkish fleet sent to help was decimated by the plague and went home towing empty ships, assisted by Genoese gold. Sampiero fought on in the hinterland.

Peace was finally brokered by Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

of England. By the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis

The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in April 1559 ended the Italian Wars (1494–1559). It consisted of two separate treaties, one between England and France on 2 April, and another between France and Spain on 3 April. Although he was not a signatory ...

in 1559, the French returned Corsica to Genoa. Left without support, Corso went again into exile. Peace was restored, but not before the Genoese had dealt severely with the traitorous Signori.

Enlightenment

Corsican society had always been relatively egalitarian, and writer Dorothy Carrington claims, "Alone among the peoples of Europe the Corsicans avoided feudal and capitalist oppression." TheAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

overthrew signorial and colonial rule and brought some measure of self-rule to the island. As the Corsican constitution

The first Corsican Constitution was drawn up in 1755 for the short-lived Corsican Republic independent from Genoa beginning in 1755, and remained in force until the annexation of Corsica by France in 1769. It was written in Tuscan Italian, the ...

was drawn up in 1755, Corsica is distinguished by having staged the first enlightenment revolution, being upstaged only by the English Revolution

The English Revolution is a term that has been used to describe two separate events in English history. Prior to the 20th century, it was generally applied to the 1688 Glorious Revolution, when James II was deposed and a constitutional monarc ...

of the preceding century. It was the first of a trio: Corsican, American, French, and as such had some influence on the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. Corsica never did obtain total sovereignty but it shared in the French Revolution, became part of France, and acquired the local autonomy and civil rights established by that revolution.

Genoese rule in the 18th century was less than satisfactory to Corsicans, who considered it corrupt and ineffective. The Genoese on their part used their citadels and watch towers in an attempt to control a population that without its assent could not be controlled. The Corsicans had a bastion of their own, the mountains, but steadily the number of exiles abroad grew and those began to look for ways and means to free Corsica from all foreign powers. At no point in the Corsican history had the island ever been a nation of its own, nor did it ever achieve that goal. In the 18th century, however, Corsicans were able to establish a partial republic in which the Genoese were penned up in the citadels but ruled nowhere else. The republic began with a search by the exiles for a savior, a man of great ability who could step in and lead them to victory and self-rule.

Revolution of 1729–36

In 1729, a full-scale revolt broke out in Corsica. In April 1731, having been unable to contain the outbreak, the Genoese appealed to theEmperor Charles VI

Charles VI (; ; 1 October 1685 – 20 October 1740) was Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy from 1711 until his death, succeeding his elder brother, Joseph I. He unsuccessfully claimed the throne of Spain follow ...

, as feudal suzerain of the island, for military assistance.Peter Hamish Wilson, ''German Armies: War and German Society, 1648–1806'' (Routledge 1998), 208. The moment was propitious, since the emperor was on good terms with the Duke of Savoy

The titles of the count of Savoy, and then duke of Savoy, are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the House of Savoy held the county. Several of these rulers ruled as kings at ...

and the King of Spain

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

, and had just signed agreement with the Maritime Powers

A maritime power (sometimes a naval power) is a nation with a very strong navy, which often is also a great power, or at least a regional power. A maritime power is able to easily control their coast, and exert influence upon both nearby and far c ...

. In July, 4,000 men of the garrison of Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

were sent to Corsica at the expense of Genoa. The Genoese desired to keep the expedition small and the cost low, but the military expert Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy-Carignano (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736), better known as Prince Eugene, was a distinguished Generalfeldmarschall, field marshal in the Army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty durin ...

convinced the emperor to increase the number of troops to 12,000 by 1732. The war degenerated into a guerrilla campaign in the mountains, which the professional forces of the emperor could not win.

After negotiations were opened, the Corsicans offered their island's sovereignty to Charles or, if he refused, Eugene. A final agreement was signed at Corte on 13 May 1732, whereby the Genoese would return to power and implement reforms. An amnesty was granted to all rebels and the emperor guaranteed the accord. The emperor was unable to prevent Genoa returning to its former mismanagement, and island rose up again in 1734.

In the second phase of the revolt, the Corsican leader, Giacinto Paoli, requested Spanish assistance. None arrived before the German adventurer Theodor von Neuhoff, who convinced the people to elect him King Theodore of Corsica

Theodore I of Corsica (25 August 169411 December 1756), born Freiherr Theodor Stephan von Neuhoff, was a low-ranking German title of nobility, usually translated "Baron". was a German adventurer who was briefly Kingdom of Corsica, King of Corsica. ...

in March 1736. He left in October 1736 to seek support abroad, and was arrested in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

and thrown in debtors' prison.

Corsican Republic

A capable advocate of Corsican independence at last stepped forward from the ranks of Corsicans in exile in Italy,

A capable advocate of Corsican independence at last stepped forward from the ranks of Corsicans in exile in Italy, Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; or ; ; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Republic of Genoa, Genoese and later Kingd ...

, a general and patriot who struggled against Genoa and then France, and became ''Il Babbu di a Patria'' (Father of the Nation). In 1755 he proclaimed the Corsican Republic. Paoli founded the first University of Corsica (with instruction in Italian). He chose the Moor's head ("Testa Mora"), previously used by Theodore of Corsica, as Corsica's emblem in 1760. Paoli considered the Corsicans to be an Italian people.

Sale and annexation to France

Seeing that attempts to dislodge Paoli were futile, in 1764 by secret treaty Genoa sold Corsica to the Duke of Choiseul, then minister of the French Navy, who bought it on behalf of the crown. On the quiet, French troops gradually replaced Genoese in the citadels. In 1768, after preparations had been made, an open treaty with Genoa ceded Corsica to France in perpetuity with no possibility of retraction and the Duke appointed a Corsican supporter, Buttafuoco, as administrator. The island rose in revolt. Paoli fought a guerrilla war against fresh French troops under their commander, Comte de Marbeuf, but was defeated in theBattle of Ponte Novu

The Battle of Ponte Novu took place on May 8 and 9, 1769, between royal French forces under the Comte de Vaux, a seasoned professional soldier with an expert on mountain warfare on his staff, and the native Corsicans under Carlo Salicetti. I ...

and had to go into exile in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

and then London. The French move into Corsica triggered the Corsican Crisis in Britain, where debate raged over the question of British intervention. In 1770, Marbeuf publicly announced the annexation of Corsica and appointed a governor.

Anglo-Corsican Kingdom

After the French revolution, Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli, who had been exiled under the monarchy, became something of an idol of liberty and democracy. In 1789 he was invited to Paris by the National Constituent Assembly and was celebrated as a hero in front of the assembly. He was afterwards sent back to Corsica having been given the rank of lieutenant-general.

In 1795, after proclaiming the independence of Corsica, a constitution was adopted that made Corsica a kingdom in

After the French revolution, Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli, who had been exiled under the monarchy, became something of an idol of liberty and democracy. In 1789 he was invited to Paris by the National Constituent Assembly and was celebrated as a hero in front of the assembly. He was afterwards sent back to Corsica having been given the rank of lieutenant-general.

In 1795, after proclaiming the independence of Corsica, a constitution was adopted that made Corsica a kingdom in personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

with Great Britain, represented by a viceroy. The constitution was considered quite democratic for its time, with an elected Parliament and a Council. Sir Gilbert Elliot served as viceroy whereas Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo

Count Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo (, , ''Karl Osipovich Potso di Borgo''; 8 March 1764 – 15 February 1842) was a Corsican politician, who later became a Russian diplomat.

He was an official representative of his homeland in Paris before ent ...

served as head of government (effectively a prime minister). The island returned to French rule in 1796.

French First Empire

Modern era

19th century

From 1854 to 1857 the Société du Télégraphe Électrique or "The Mediterranean Electric Telegraph", a company started by John Watkins Brett, connectedLa Spezia

La Spezia (, or ; ; , in the local ) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second-largest city in the Liguria ...

, Italy with Corsica by submarine cable, being the first to do so. The line ran south along the east coast, partly on land, partly on sea, from Cap Corse

Cap Corse (; , ; , ), a geographical area of Corsica, is a long peninsula located at the northern tip of the island. At the base of it is the second largest city in Corsica, Bastia. Cap Corse is also a Communauté de communes comprising 18 comm ...

to Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French language, French: ; or ; , locally: ; ) is the capital and largest city of Corsica, France. It forms a communes of France, French commune, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Corse-du-Sud, and head o ...

, where a second cable crossed the Strait of Bonifacio

The Strait of Bonifacio (; ; ; ; ; ; ) is the strait between Corsica and Sardinia, named after the Corsican town Bonifacio. It is wide and divides the Tyrrhenian Sea from the western Mediterranean Sea. The strait is notorious among sailors for i ...

. Brett's intended links across Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and through the deeps to Bona, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, failed because of decimation of the crews by malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and the technical difficulties of laying cable in deep waters. By 1870 Paris could communicate with Algeria by telegraph through Corsica.

First World War and after

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

Corsica responded to the call to arms more intensely than any other allied region. Out of a population estimated by a diplomat of the times to have been about 300,000, some 50,000 Corsican men were under arms: a ratio greater than one of every six Corsican citizens.

The civilian population was correspondingly pro-allied. Prisoners of war were sent to Corsica. There they occupied every available space from rooms in monasteries to cells in citadels. Stone sheds were converted for their use. When all else failed, wooden barracks were constructed on the mountainsides. The prisoners were put to work in agriculture and forestry. Corsica was also turned into a hospital for the wounded. Most of the allies sent medical units or volunteers. The island was so useful as a base that the sea lanes leading to it were under constant surveillance and attack by U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s.

Corsican poilus fought loyally and with valor. Estimates of casualties vary but most are over 50%. As a result, the survivors became established in the upper echelons of the French military and police. However, the loss of manpower contributed to a recession and mass exodus from Corsica in favor of southern France in the post-war period. Corsicans of means became colonizers during this period, the descendants of the former signori starting agricultural enterprises in Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

. It was on them that the blow of subsequent wars of independence fell most heavily.

Second World War

After the Allied defeat of 1940, Corsica became part of the Southern zone of

After the Allied defeat of 1940, Corsica became part of the Southern zone of Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

, and was thus not directly occupied by Axis forces, but fell under ultimate military control of Nazi Germany. A campaign of rhetoric by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

asserting that Corsica belonged to Italy was reinforced by the irredentist movement of Italian-speaking Corsicans (such as Petru Giovacchini) who advocated the unification of the island with Italy.

In November 1942, as part of its invasion of the southern zone, Germany arranged for fascist Italy to occupy Corsica as well as some parts of France up to the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ròse''; Franco-Provençal, Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before dischargi ...

river. The Italian occupation force in Corsica grew to over 85,000 troops, later reinforced by 12,000 German troops. The French had no troops with which to prevent the occupation. Irredentist propaganda intensified, but the préfet

A prefect (, plural , both ) in France is the State's representative in a department or region. Regional prefects are ''ex officio'' the departmental prefects of the regional prefecture. Prefects are tasked with upholding the law in the departme ...

representing the French government restated French sovereignty over the island and stated that the Italian troops were occupiers.

The French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

soon began developing under the impetus of loyal local inhabitants (the Maquis named after the 18th-century partisans of Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; or ; ; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Republic of Genoa, Genoese and later Kingd ...

), and of Free French

Free France () was a resistance government

claiming to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third French Republic, Third Republic during World War II. Led by General , Free France was established as a gover ...

leaders starting in December 1942, with Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

eventually sending Paulin Colonna d'Istria from Algeria to unite the movements. Boosted via six visits by the Free French submarine ''Casabianca'', and further armed by Allied airdrops, the strengthened Resistance was met with fierce repression by the OVRA (Italian fascist police) and the fascist Black Shirts paramilitary groups but gained strength, especially in the countryside.

In July 1943, following the Fall of the Fascist regime in Italy

The Fall of the Fascist regime in Italy, also known in Italy as (, ; ), came as a result of parallel plots led respectively by Count Dino Grandi and King Victor Emmanuel III during the spring and summer of 1943, culminating with a successfu ...

, 12,000 German troops came to Corsica. They formally took over the occupation on 9 September 1943, the day after the Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile ( Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Italy and the Allies, marking the end of hostilities between Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was made public ...

. Following the Allied landings in Sicily and the Italian surrender, these German troops were joined by the remnants of the Africa Division of the German army, reconstituted as the 90th Panzergrenadier Division with about 40,000 men, which crossed over from Sardinia. They were accompanied by some Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

forces. They faced Resistance forces which had been asked to occupy the mountains to prevent Axis troop movements between the Corsican coasts, as well as a subset of Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

troops that allied with them but whose contribution was hampered as their leadership was ambivalent. The German forces retreated from Bonifacio towards the Northern harbor of Bastia

Bastia ( , , , ; ) is a communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Haute-Corse, Corsica, France. It is located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It also has the second-highest popu ...

. Elements of the reconstituted French I Corps, from the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division

The 4th Moroccan Mountain Division () was an infantry division of the Army of Africa () which participated in World War II.

Created in Morocco following the liberation of French North Africa, the division fought in Corsica, Italy, metropolitan ...

, landed in Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French language, French: ; or ; , locally: ; ) is the capital and largest city of Corsica, France. It forms a communes of France, French commune, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Corse-du-Sud, and head o ...

to counter the German movement and the Germans evacuated Bastia by 4 October 1943, leaving behind 700 dead and 350 POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

.

After Corsica was thus liberated from the forces of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

, the island started functioning as an Allied air base in support of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations

The Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army (MTOUSA), originally called the North African Theater of Operations, United States Army (NATOUSA), was a military formation of the United States Army that supervised all U.S. Army for ...

in 1944; in particular, groups of the 57th Bomb Wing were stationed along the east coast from Bastia in the north to Solenzara in the south. Corsica was also one of the bases from which Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil), known as Débarquement de Provence in French ("Provence Landing"), was the code name for the landing operation of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Provence (Southern France) on 15Augu ...

, the invasion of southern France in August 1944, was launched.

While on the island, U.S. Army engineers successfully eradicated the malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

that had been endemic to the coastal areas of Corsica, including half the island's arable land that had been previously uninhabitable.

Modern era