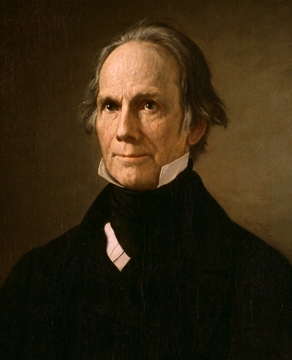

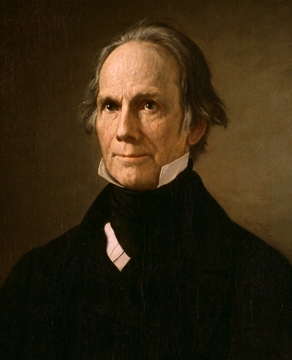

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented

Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

in both the

U.S. Senate and

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

. He was the seventh

House speaker as well as the ninth

secretary of state. He unsuccessfully ran for president in the

1824

Events

January–March

* January 1 – John Stuart Mill begins publication of The Westminster Review. The first article is by William Johnson Fox

* January 8 – After much controversy, Michael Faraday is finally elected as a member of th ...

,

1832, and

1844

In the Philippines, 1844 had only 365 days, when Tuesday, December 31 was skipped as Monday, December 30 was immediately followed by Wednesday, January 1, 1845, the next day after. The change also applied to Caroline Islands, Guam, Marian ...

elections. He helped found both the

National Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States which evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

and the

Whig Party. For his role in defusing sectional crises, he earned the appellation of the "Great Compromiser" and was part of the "

Great Triumvirate

In U.S. politics, the Great Triumvirate (known also as the Immortal Trio) was a triumvirate of three statesmen who dominated American politics for much of the first half of the 19th century, namely Henry Clay of Kentucky, Daniel Webster of M ...

" of Congressmen, alongside fellow Whig

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

and

Democrat John C. Calhoun.

Clay was born in

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, in 1777, and began his legal career in

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the List of ...

, in 1797. As a member of the

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

, Clay won election to the Kentucky state legislature in 1803 and to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1810. He was chosen as Speaker of the House in early 1811 and, along with President

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, led the United States into the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

against Great Britain. In 1814, he helped negotiate the

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, which brought an end to the War of 1812, and then after the war, Clay returned to his position as Speaker of the House and developed the

American System, which called for federal

infrastructure investments, support for the

national bank, and high protective

tariff rates. In 1820 he helped bring an end to a sectional crisis over

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

by leading the passage of the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

. Clay finished with the fourth-most electoral votes in the multi-candidate

1824-1825 presidential election and used his position as speaker to help

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

win the

contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

held to select the president. President Adams then appointed Clay to the prestigious position of secretary of state; as a result, critics alleged that the two had agreed to a "

corrupt bargain

In American political jargon, corrupt bargain is a backdoor deal for or involving the U.S. presidency. Three events in particular in American political history have been called the corrupt bargain: the 1824 United States presidential election, ...

".

Despite receiving support from Clay and other National Republicans, Adams was defeated by Democrat

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

in the

1828 presidential election. Clay won election to the Senate in 1831 and ran as the National Republican nominee in the 1832 presidential election. Clay was defeated decisively by President Jackson primarily due to his support for the

national bank, which Jackson vehemently opposed. After the 1832 election, Clay helped bring an end to the

nullification crisis by leading passage of the

Tariff of 1833

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

. During Jackson's second term, opponents of the president including Clay, Webster, and

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

created the Whig Party, and through the years, Clay became a leading congressional Whig.

Clay sought the presidency in the

1840 election but was passed over at the

Whig National Convention in favor of Harrison. When Harrison died and his vice president

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

ascended to office in 1841, Clay clashed with Tyler, who broke with Clay and other congressional Whigs. Clay resigned from the Senate in 1842 and won the 1844 Whig presidential nomination, but he was narrowly defeated in the general election by Democrat

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

, who made the annexation of the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

his top issue. Clay strongly criticized the subsequent

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

and sought the Whig presidential nomination in

1848 but was passed over in favor of General

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

who went on to win the election. After returning to the Senate in 1849, Clay played a key role in passing the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

, which postponed a crisis over the status of slavery in the territories. Clay was one of the most important and influential political figures of his era.

Early life

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, at the Clay homestead in

Hanover County, Virginia

Hanover County is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 109,979. Its county seat is Hanover, Virginia, Hanover.

Hanove ...

. He was the seventh of nine children born to the Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth (née Hudson) Clay. Almost all of Henry's older siblings died before adulthood.

His father, a

Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister nicknamed "Sir John", died in 1781, leaving Henry and his brothers two enslaved individuals each; he also left his wife 18 slaves and of land. Clay was of entirely

English descent; his ancestor, John Clay, settled in Virginia in 1613. The

Clay family became a well-known political family including three other US senators, numerous state politicians, and Clay's cousin

Cassius Clay, a prominent anti-slavery activist active in the mid-19th century.

The British raided Clay's home shortly after the death of his father, leaving the family in a precarious economic position. However, the widow Elizabeth Clay married Captain Henry Watkins, a successful

planter and cousin to John Clay. Elizabeth would have seven more children with Watkins, bearing a total of sixteen children. Watkins became a kind and supportive stepfather and Clay had a very good relationship with him. After his mother's remarriage, the young Clay remained in Hanover County, where he learned how to read and write. In 1791, Watkins moved the family to Kentucky, joining his brother in the pursuit of fertile new lands in the West. However, Clay did not follow, as Watkins secured his temporary employment in a

Richmond emporium, with the promise that Clay would receive the next available clerkship at the

Virginia Court of Chancery.

After Clay had worked at the Richmond emporium for a year, he obtained a clerkship that had become available at the Virginia Court of Chancery. Clay adapted well to his new role, and his handwriting earned him the attention of

College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public university, public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III of England, William III and Queen ...

professor

George Wythe, a signer of the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, mentor of

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, and judge on Virginia's High Court of Chancery. Hampered by a crippled hand, Wythe chose Clay as his secretary and

amanuensis

An amanuensis ( ) ( ) or scribe is a person employed to write or type what another dictates or to copy what has been written by another. It may also be a person who signs a document on behalf of another under the latter's authority.

In some aca ...

, a role in which Clay would remain for four years. Clay began to

read law

Reading law was the primary method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship un ...

under Wythe's mentorship. Wythe had a powerful effect on Clay's worldview, with Clay embracing Wythe's belief that the example of the United States could help spread human freedom around the world. Wythe subsequently arranged a position for Clay with Virginia attorney general

Robert Brooke, with the understanding that Brooke would finish Clay's legal studies. After completing his studies under Brooke, Clay was

admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1797.

Marriage and family

On April 11, 1799, Clay married Lucretia Hart (1781–1864) at the Hart home in

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the List of ...

. Her father, Colonel Thomas Hart, was an early settler of Kentucky and a prominent businessman. Hart proved to be an important business connection for Clay, as he helped Clay gain new clients and grow in professional stature. Hart was the namesake and grand-uncle of Missouri Senator

Thomas Hart Benton and was also related to

James Brown

James Joseph Brown (May 3, 1933 – December 25, 2006) was an American singer, songwriter, dancer, musician, and record producer. The central progenitor of funk music and a major figure of 20th-century music, he is referred to by Honorific nick ...

, a prominent Louisiana politician, and

Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was an American politician and military officer who was the List of governors of Kentucky, first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Ca ...

, the first

governor of Kentucky

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; sinc ...

. Henry and Lucretia would remain married until his death in 1852; she lived until 1864, dying at the age of 83. Both are buried at

Lexington Cemetery.

Clay and Lucretia had eleven children (six daughters and five sons):

Henrietta (born in 1800), Theodore (1802), Thomas (1803), Susan (1805), Anne (1807), Lucretia (1809),

Henry Jr. (1811), Eliza (1813), Laura (1815),

James (1817), and

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

(1821). By 1835, all six daughters had died of varying causes, two when very young, two as children, and the last two as young mothers. Henry Jr. was killed while commanding a regiment at the

Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between U.S. forces, largely vol ...

during the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. Clay's oldest son, Theodore Wythe Clay, spent the second half of his life confined to a

psychiatric hospital

A psychiatric hospital, also known as a mental health hospital, a behavioral health hospital, or an asylum is a specialized medical facility that focuses on the treatment of severe Mental disorder, mental disorders. These institutions cater t ...

. When a young child, Theodore was injured by a blow to his head that fractured his skull. As he grew older his condition devolved into insanity, and from 1831 until his death in 1870 he was confined to

an asylum in Lexington.

Thomas (who had served some jail time in Philadelphia in 1829–1830)

became a successful farmer, James established a legal practice (and later served in Congress), and John (who in his mid-20s was also confined to the asylum for a short time) became a successful horse breeder.

Clay was greatly interested in gambling, although he favored numerous restrictions and legal limitations on it. Famously, he once won $40,000 (approximately $970,000 as of 2020). Clay asked for $500 (approximately $12,000 today) and waived the remainder of the debt. Shortly afterward, Clay fell into a debt of $60,000 (approximately $1.5 million today) while gambling with the same man, who then asked for the $500 back and waived the rest of the debt.

They initially lived in Lexington, but in 1804 they began building a

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

outside of Lexington known as

Ashland. The Ashland estate eventually encompassed over , with numerous outbuildings such as a smokehouse, a greenhouse, and several barns. There were 122 enslaved people at the estate during Clay's lifetime, with about 50 people needed for farming and the household.

He planted crops such as corn, wheat, and rye, as well as

hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a plant in the botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial and consumable use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest ...

, the chief crop of the

Bluegrass region

The Bluegrass region is a geographic region in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It makes up the central and northern part of the state, roughly bounded by the cities of Frankfort, Kentucky, Frankfort, Paris, Kentucky, Paris, Richmond, Kentucky, Ric ...

. Clay also took a strong interest in

thoroughbred racing

Thoroughbred racing is a sport and industry involving the racing of Thoroughbred horses. It is governed by different national bodies. There are two forms of the sport – flat racing and jump racing, the latter known as National Hunt racing in ...

and imported livestock such as

Arabian horse

The Arabian or Arab horse ( , DIN 31635, DMG ''al-ḥiṣān al-ʿarabī'') is a horse breed, breed of horse with historic roots on the Arabian Peninsula. With a distinctive head shape and high tail carriage, the Arabian is one of the most easi ...

s,

Maltese donkeys, and

Hereford cattle

The Hereford is a British List of cattle breeds, breed of beef cattle originally from Herefordshire in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It was the result of selective breeding from the mid-eighteenth century by a few famil ...

. Though Clay suffered some financial issues during economic downturns, he never fell deeply into debt and ultimately left his children a large inheritance. After the deaths of Anne and Susan, Clay and Lucretia raised several grandchildren at Ashland.

Early career in law and politics

Legal career

In November 1797, Clay relocated to Lexington, Kentucky, near where his parents and siblings resided. The Bluegrass region, with Lexington at its center, had quickly grown in the preceding decades but had only recently stopped being under the threat of

Native American raids. Lexington was an established town that hosted

Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky, United States. It was founded in 1780 and is the oldest university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is Higher educ ...

, the first university west of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

. Having already passed the Virginia Bar, Clay quickly received a Kentucky license to practice law. After apprenticing himself to Kentucky attorneys such as

George Nicholas,

John Breckenridge, and James Brown, Clay established his own law practice, frequently working on debt collections and land disputes. Clay soon established a reputation for strong legal ability and courtroom oratory. In 1805, he was appointed to the faculty of Transylvania University where he taught, among others, future Kentucky Governor

Robert P. Letcher and Robert Todd, the future father-in-law of

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

.

Clay's most notable client was

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician, businessman, lawyer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805 d ...

, who was indicted for treason in the

Burr conspiracy. Clay and his law partner

John Allen successfully defended Burr without a fee in 1807. Thomas Jefferson later convinced Clay that Burr had been guilty of the charges. Clay's legal practice was light after his election to Congress. In the 1823 case ''

Green v. Biddle'', Clay submitted the

Supreme Court's first

amicus curiae

An amicus curiae (; ) is an individual or organization that is not a Party (law), party to a legal case, but that is permitted to assist a court by offering information, expertise, or insight that has a bearing on the issues in the case. Wheth ...

. However, he lost that case.

Early political career

Clay entered politics shortly after arriving in Kentucky. In his first political speech, he attacked the

Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were a set of four United States statutes that sought, on national security grounds, to restrict immigration and limit 1st Amendment protections for freedom of speech. They were endorsed by the Federalist Par ...

, laws passed by Federalists to suppress dissent during the

Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

with France. Like most Kentuckians, Clay was a member of the

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

, but he clashed with state party leaders over a state constitutional convention. Using the pseudonym "Scaevola" (in reference to

Gaius Mucius Scaevola), Clay advocated for direct elections for Kentucky elected officials and the

gradual emancipation of

slavery in Kentucky. The 1799

Kentucky Constitution included the direct election of public officials, but the state did not adopt Clay's plan for gradual emancipation.

In 1803, Clay won election to the

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

. His first legislative initiative was the partisan

gerrymander

Gerrymandering, ( , originally ) defined in the contexts of Representative democracy, representative electoral systems, is the political manipulation of Boundary delimitation, electoral district boundaries to advantage a Political party, pa ...

of Kentucky's

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

districts, which ensured that all of Kentucky's presidential electors voted for President Jefferson in the

1804 presidential election. Clay clashed with legislators who sought to reduce the power of Clay's Bluegrass region, and he unsuccessfully advocated moving the state capitol from

Frankfort to Lexington. Clay frequently opposed populist firebrand

Felix Grundy

Felix Grundy (September 11, 1777 – December 19, 1840) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 13th United States Attorney General. He also had served several terms as a congressman and as a U.S. senator from Tennessee. He ...

, and he helped defeat Grundy's effort to revoke the banking privileges of the state-owned Kentucky Insurance Company. He advocated for the construction of

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

, which would become a consistent theme throughout his public career. Clay's influence in Kentucky state politics was such that in 1806 the Kentucky legislature elected him to the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

. During his two-month tenure in the Senate, Clay advocated for the construction of various bridges and canals, including

a canal connecting the

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

and the

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

.

After Clay returned to Kentucky in 1807, he was elected as the speaker of the state house of representatives. That same year, in response to attacks on American shipping by Britain and France during the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, President Jefferson arranged passage of the

Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. Much broader than the ineffectual 1806 Non-importation Act, it represented an escalation of attempts to persuade Br ...

. In support of Jefferson's policy, which limited trade with foreign powers, Clay introduced a resolution to require legislators to wear

homespun suits rather than those made of imported British

broadcloth. The vast majority of members of the state house voted for the measure, but

Humphrey Marshall, an "aristocratic lawyer who possessed a sarcastic tongue," voted against it. In early 1809, Clay challenged Marshall to a

duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and later the small sword), but beginning in ...

, which took place on January 19. While many contemporary duels were called off or fought without the intention of killing one another, both Clay and Marshall fought the duel with the intent of killing their opponent. They each had three turns to shoot; both were hit by bullets, but both survived. Clay quickly recovered from his injury and received only a minor

censure

A censure is an expression of strong disapproval or harsh criticism. In parliamentary procedure, it is a debatable main motion that could be adopted by a majority vote. Among the forms that it can take are a stern rebuke by a legislature, a sp ...

from the Kentucky legislature.

In 1810, U.S. Senator

Buckner Thruston

Buckner Thruston (February 9, 1763 – August 30, 1845) was an American lawyer, slaveowner and politician who served as United States Senator from Kentucky as well as in the Virginia House of Delegates and became a United States circuit judge o ...

resigned to accept appointment to a position as a federal judge, and Clay was selected by the legislature to fill Thruston's seat. Clay quickly emerged as a fierce critic of British attacks on American shipping, becoming part of an informal group of "

war hawks" who favored expansionist policies. He also advocated the annexation of

West Florida

West Florida () was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. Great Britain established West and East Florida in 1763 out of land acquired from France and S ...

, which was controlled by Spain. On the insistence of the Kentucky legislature, Clay helped prevent the re-charter of the

First Bank of the United States

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a National bank (United States), national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress ...

, arguing that it interfered with state banks and infringed on

states' rights

In United States, American politics of the United States, political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments of the United States, state governments rather than the federal government of the United States, ...

. After serving in the Senate for one year, Clay decided that he disliked the rules of the Senate and instead sought election to the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

. He won election unopposed in late 1810.

Speaker of the House

Election and leadership

The

1810–1811 elections produced many young, anti-British members of Congress who, like Clay, supported going to war with Great Britain. Buoyed by the support of fellow

war hawks, Clay was elected

Speaker of the House for the

12th Congress. At 34, he was the youngest person to become speaker, a distinction he held until 1839, when 30-year-old

Robert M. T. Hunter

Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter (April 21, 1809 – July 18, 1887) was an American lawyer, politician and planter. He was a United States House of Representatives, U.S. representative (1837–1843, 1845–1847), Speaker of the United ...

took office. He was also the first of only two new members elected speaker to date, the other being

William Pennington in 1860.

Between 1810 and 1824, Clay was elected to seven terms in the House. His tenure was interrupted from 1814 to 1815 when he was a commissioner to peace talks with the British in

Ghent

Ghent ( ; ; historically known as ''Gaunt'' in English) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the Provinces of Belgium, province ...

,

United Netherlands to end the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, and from 1821 to 1823, when he left Congress to rebuild his family's fortune in the aftermath of the

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

.

Elected speaker six times, Clay's cumulative tenure in office of 10 years, 196 days, is the second-longest, surpassed only by

Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

.

As speaker, Clay wielded considerable power in making committee appointments, and like many of his predecessors he assigned his allies to important committees. Clay was exceptional in his ability to control the legislative agenda through well-placed allies and the establishment of new committees and departed from precedent by frequently taking part in floor debates. Yet he also gained a reputation for personal courteousness and fairness in his rulings and committee appointments. Clay's drive to increase the power of the office of speaker was aided by President

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, who deferred to Congress in most matters.

John Randolph, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party but also a member of the "

tertium quids" group that opposed many federal initiatives, emerged as a prominent opponent of Speaker Clay. While Randolph frequently attempted to obstruct Clay's initiatives, Clay became a master of parliamentary maneuvers that enabled him to advance his agenda even over the attempted obstruction by Randolph and others.

Madison administration, 1811–1817

Clay and other war hawks demanded that the British revoke the

Orders in Council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

, a series of decrees that had resulted in a de facto commercial war with the United States. Though Clay recognized the dangers inherent in fighting Britain, one of the most powerful countries in the world, he saw it as the only realistic alternative to a humiliating submission to British attacks on American shipping. Clay led a successful effort in the House to

declare war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gover ...

against Britain, complying with a request from President Madison. Madison signed the declaration of war on June 18, 1812, beginning the War of 1812. During the war, Clay frequently communicated with Secretary of State

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

and Secretary of War

William Eustis, though he advocated for the replacement of the latter. The war started poorly for the Americans, and Clay lost friends and relatives in the fighting. In October 1813, the British asked Madison to begin negotiations in Europe, and Madison asked Clay to join his diplomatic team, as the president hoped that the presence of the leading war hawk would ensure support for a peace treaty. Clay was reluctant to leave Congress but felt duty-bound to accept the offer, and so he resigned from Congress on January 19, 1814.

Clay left the country on February 25, but negotiations with the British did not begin until August 1814. Clay was part of a team of five commissioners that included Treasury Secretary

Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan-American politician, diplomat, ethnologist, and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

, Senator

James Bayard, ambassador

Jonathan Russell

Jonathan Russell (February 27, 1771 – February 17, 1832) was a United States representative from Massachusetts and diplomat. He served the Massachusetts's 11th congressional district, 11th congressional district from 1821 to 1823 and was the ...

, and ambassador

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, the head of the American team. Clay and Adams maintained an uneasy relationship marked by frequent clashes, and Gallatin emerged as the unofficial leader of the American team. When the British finally presented their initial peace offer, Clay was outraged by its terms, especially the British proposal for an

Indian barrier state on the

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

. After a series of American military successes in 1814, the British delegation made several concessions and offered a better peace deal. While Adams and Gallatin were eager to make peace as quickly as possible even if that required sub-optimal terms in the peace treaty, Clay believed that the British, worn down by years of fighting against France, greatly desired peace with the United States. Partly due to Clay's hard-line stance, the

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

included relatively favorable terms for the United States, essentially re-establishing the ''

status quo ante bellum

The term is a Latin phrase meaning 'the situation as it existed before the war'.

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When used as such, it means that no ...

'' between Britain and the U.S. The treaty was signed on December 24, 1814, bringing a close to the War of 1812. After the signing of the treaty, Clay briefly traveled to London, where he helped Gallatin negotiate a commercial agreement with Britain.

Clay returned to the United States in September 1815; despite his absence, he had been elected to another term in the House of Representatives. Upon his return to Congress, Clay won election as Speaker of the House. The War of 1812 strengthened Clay's support for interventionist economic policies such as federally funded internal improvements, which he believed were necessary to improve the country's infrastructure system. He eagerly embraced President Madison's ambitious domestic package, which included infrastructure investment,

tariffs

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials and is ...

to

protect domestic manufacturing, and spending increases for the army and navy. With the help of

John C. Calhoun and

William Lowndes, Clay passed the

Tariff of 1816

The Tariff of 1816, also known as the Dallas Tariff, is notable as the first tariff passed by Congress with an explicit function of protecting U.S. manufactured items from overseas competition. Prior to the War of 1812, tariffs had primarily se ...

, which served the dual purpose of raising revenue and protecting American manufacturing. To stabilize the currency, Clay and Treasury Secretary

Alexander Dallas arranged passage of a bill establishing the

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Second Report on Public Credit, Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January ...

(also known as the national bank). Clay also supported the

Bonus Bill of 1817

The Bonus Bill of 1817 was legislation proposed by John C. Calhoun to earmark the revenue "bonus," as well as future dividends, from the recently established Second Bank of the United States for an internal improvements fund.Stephen MinicucciIn ...

, which would have provided a fund for internal improvements, but Madison vetoed the bill on constitutional concerns. Beginning in 1818, Clay advocated for an economic plan known as the "

American System," which encompassed many of the economic measures, including protective tariffs and infrastructure investments, that he helped pass in the aftermath of the War of 1812.

Monroe administration, 1817–1825

Like Jefferson and

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, President Madison decided to retire after two terms, leaving open the Democratic-Republican nomination for the

1816 presidential election. At the time, the Democratic-Republicans used a

congressional nominating caucus

The congressional nominating caucus is the name for informal meetings in which American congressmen would agree on whom to nominate for the presidency and vice presidency from their political party.

History

The system was introduced after George ...

to choose their presidential nominees, giving congressmen a powerful role in the presidential selection process. Monroe and Secretary of War

William Crawford emerged as the two main candidates for the Democratic-Republican nomination. Clay had a favorable opinion of both individuals, but he supported Monroe, who won the nomination and went on to defeat Federalist candidate

Rufus King

Rufus King (March 24, 1755April 29, 1827) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father, lawyer, politician, and diplomat. He was a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convent ...

in the general election. Monroe offered Clay the position of secretary of war, but Clay strongly desired the office of secretary of state and was angered when Monroe instead chose John Quincy Adams for that position. Clay became so bitter that he refused to allow Monroe's inauguration to take place in the House Chamber and subsequently did not attend Monroe's outdoor inauguration.

In early 1819, a dispute erupted over the proposed statehood of

Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

after New York Congressman

James Tallmadge introduced a

legislative amendment that would provide for the gradual emancipation of Missouri's enslaved people. Though Clay had previously called for gradual emancipation in Kentucky, he sided with fellow Southerners in voting down Tallmadge's amendment. Clay instead supported Illinois Senator

Jesse B. Thomas's compromise proposal in which Missouri would be admitted as a

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

,

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

would be admitted as a free state, and slavery would be forbidden in the territories north of 36° 30' parallel. Clay helped assemble a coalition that passed the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

, as Thomas's proposal became known. Further controversy ensued when Missouri's constitution banned free blacks from entering the state, but Clay was able to engineer another compromise that allowed Missouri to join as a state in August 1821.

In foreign policy, Clay was a leading American supporter of the

independence movements and revolutions that broke out in

Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

beginning in 1810. Clay frequently called on the Monroe administration to recognize the fledgling Latin American republics, but Monroe feared that doing so would derail his plans to acquire

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

. In 1818, General

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

crossed into Spanish Florida to suppress raids by

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

Indians. Though Jackson was following Monroe's implied wishes in entering Florida, he created additional controversy in seizing the Spanish town of

Pensacola

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only city in Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Pensacola metropolitan area, which ha ...

. Despite protests from Secretary of War Calhoun, Monroe and Adams decided to support Jackson's actions in the hope that they would convince Spain to sell Florida. Clay, however, was outraged, and he publicly condemned Jackson's decision to hang two foreign nationals without a trial. Before the House chamber, he compared Jackson to military dictators of the past, telling his colleagues "that Greece had her

Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

,

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

her

Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war. He ...

, England her

Cromwell, France her

Bonaparte, and, that if we would escape the rock on which they split, we must avoid their errors." Jackson saw Clay's protestations as an attack on his character and thus began a long rivalry between Clay and Jackson. The rivalry and the controversy over Jackson's expedition temporarily subsided after the signing of the

Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to ...

, in which the U.S. purchased Florida and delineated its western boundary with

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

.

1824 presidential election

By 1822, several members of the Democratic-Republican Party had begun exploring presidential bids to succeed Monroe, who planned to retire after two terms like his predecessors. As the Federalist Party was near collapse, the 1824 presidential election would be contested only by members of the Democratic-Republican Party, including Clay. Having led the passage of the

Tariff of 1824 and the

General Survey Act, Clay campaigned on his American System of high tariffs and federal spending on infrastructure. Three members of Monroe's Cabinet, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, appeared to be Clay's strongest competitors for the presidency. Though many, including Clay, did not take his candidacy seriously at first, General Andrew Jackson emerged as a presidential contender, eroding Clay's base of support in the western states. In February 1824, the sparsely attended Democratic-Republican congressional caucus endorsed Crawford's candidacy, but Crawford's rivals ignored the caucus results, and various state legislatures nominated candidates for president. During the campaign, Crawford suffered a major stroke, while Calhoun withdrew from the race after Jackson won the endorsement of the Pennsylvania legislature.

By 1824, with Crawford still in the race, Clay concluded that no candidate would win a majority of electoral votes; in that scenario, the House of Representatives would hold a

contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

to decide the election. Under the terms of the

Twelfth Amendment, the top three electoral vote-getters would be eligible to be elected by the House. Clay was confident that he would prevail in a contingent held in the chamber he presided over, so long as he was eligible for election. Clay won Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri, but his loss in New York and Louisiana relegated him to a fourth-place finish behind Adams, Jackson, and Crawford. Clay was humiliated that he finished behind the invalid Crawford and Jackson, but supporters of the three remaining presidential candidates immediately began courting his support for the contingent election.

For various reasons, supporters of all three candidates believed they had the best chance of winning Clay's backing, but Clay quickly settled on supporting Adams. Of the three candidates, Adams was the most sympathetic to Clay's American System, and Clay viewed both Jackson and the sickly Crawford as unsuitable for the presidency. On January 9, 1825, Clay privately met with Adams for three hours, after which Clay promised Adams his support; both would later claim that they did not discuss Clay's position in an Adams administration. With the help of Clay, Adams won the House vote on the first ballot. After his election, Adams offered Clay the position of secretary of state, which Clay accepted, despite fears that he would be accused of trading his support for the

Cabinet post. Jackson was outraged by the election, and he and his supporters accused Clay and Adams of having reached a "

Corrupt Bargain

In American political jargon, corrupt bargain is a backdoor deal for or involving the U.S. presidency. Three events in particular in American political history have been called the corrupt bargain: the 1824 United States presidential election, ...

." Pro-Jackson forces immediately began preparing for the

1828 presidential election, with the Corrupt Bargain accusation becoming their central issue.

Secretary of State

Clay served as secretary of state from 1825 to 1829. As secretary of state, he was the top foreign policy official in the Adams administration, but he also held several domestic duties, such as oversight of the patent office. Clay came to like Adams, a former rival, and to despise Jackson. They developed a strong working relationship. Adams and Clay were both wary of forming entangling alliances with the emerging states, and they continued to uphold the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

, which called for European non-intervention in former colonies. Clay was rebuffed in his efforts to reach a commercial treaty and a settlement of the

Canada–United States border

The international border between Canada and the United States is the longest in the world by total length. The boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is long. The land border has two sections: Canada' ...

with Britain, and was also unsuccessful in his attempts to make the French pay for damages arising from attacks on American shipping during the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. He had more success in negotiating commercial treaties with Latin American republics, reaching "

most favoured nation

In international economic relations and international politics, most favoured nation (MFN) is a status or level of treatment accorded by one state to another in international trade. The term means the country which is the recipient of this treatme ...

" trade agreements in an attempt to ensure that no European country had a trading advantage over the United States. Seeking deeper relations with Latin American countries, Clay strongly favored sending American delegates to the

Congress of Panama

The Congress of Panama (also referred to as the Amphictyonic Congress, in homage to the Amphictyonic League of Ancient Greece) was a congress organized by Simón Bolívar in 1826 with the goal of bringing together the new republics of Latin Ameri ...

, but his efforts were defeated by opponents in the Senate.

Adams proposed an ambitious domestic program based in large part on Clay's American System, but Clay warned the president that many of his proposals held little chance of passage in the

19th Congress. Adams's opponents defeated many of his proposals, including the establishment of a naval academy and a national observatory, but Adams did preside over the construction or initiation of major infrastructure projects like the

National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and was a main tran ...

and the

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal and occasionally called the Grand Old Ditch, operated from 1831 until 1924 along the Potomac River between Washington, D.C., and Cumberland, Maryland. It replaced the Patowmack Canal ...

. Followers of Adams began to call themselves

National Republicans, and Jackson's followers became known as

Democrats. Both campaigns spread untrue stories about the opposing candidates. Adams' followers denounced Jackson as a

demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

, and some Adams-aligned papers accused Jackson's wife

Rachel

Rachel () was a Bible, Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph (Genesis), Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban (Bible), Laban. Her older siste ...

of

bigamy

In a culture where only monogamous relationships are legally recognized, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their mar ...

. Though Clay was not directly involved in these attacks, his failure to denounce them earned him the lifelong enmity of Jackson.

Clay was one of Adams's most important political advisers, but because of his myriad responsibilities as secretary of state, he was often unable to take part in campaigning. As Adams was averse to the use of patronage for political purposes, Jackson's campaign enjoyed a marked advantage in organization, and Adams' allies such as Clay and

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

were unable to create an equally powerful organization headed by the president. In the 1828 election, Jackson took 56% of the popular vote and won almost every state outside of

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

; Clay was especially distressed by Jackson's victory in Kentucky. The election result represented not only the victory of a man Clay viewed as unqualified and unprincipled but also a rejection of Clay's domestic policies.

Later career

Jackson administration, 1829–1837

Return to the Senate

Even with Clay out of office, President Jackson continued to see Clay as one of his major rivals, and Jackson at one point suspected Clay of being behind the

Petticoat affair, a controversy involving the wives of his Cabinet members. Clay strongly opposed the 1830

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

, which authorized the administration to relocate Native Americans to land west of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. Another key point of contention between Clay and Jackson was the proposed

Maysville Road, which would connect

Maysville, Kentucky, to the National Road in

Zanesville, Ohio

Zanesville is a city in Muskingum County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Located at the confluence of the Licking River (Ohio), Licking and Muskingum River, Muskingum rivers, the city is approximately east of Columbus, Ohio, Columb ...

; transportation advocates hoped that later extensions would eventually connect the National Road to

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. In 1830, Jackson vetoed the project both because he felt that the road did not constitute interstate commerce, and also because he generally opposed using the federal government to promote economic modernization. While Jackson's veto garnered support from opponents of infrastructure spending, it damaged his base of support in Clay's home state of Kentucky. Clay returned to federal office in 1831 by winning election to the Senate over

Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth vice president of the United States from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren. He is ...

in a 73 to 64 vote of the Kentucky legislature. His return to the Senate after 20 years, 8 months, 7 days out of office, marks the fourth-longest gap in service to the chamber in history.

Bank War and the 1832 presidential election

With the defeat of Adams, Clay became the de facto leader of the National Republicans, and he began making preparations for a presidential campaign in the

1832 election. In 1831, Jackson made it clear that he was going to run for re-election, ensuring that support or opposition to his presidency would be a central feature of the upcoming race. Jackson's Democrats rallied around his policies towards the national bank, internal improvements,

Indian removal, and

nullification, but these policies also earned Jackson various enemies, including Vice President John C. Calhoun. However, Clay rejected overtures from the fledgling

Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest Third party (United States), third party in the United States. Formally a Single-issue politics, single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry in the United States. It was active from the late 1820s, ...

, and his attempt to convince Calhoun to serve as his running mate failed, leaving the opposition to Jackson split among different factions. Inspired by the Anti-Masonic Party's national convention, Clay's National Republican followers arranged for a

national convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

that nominated Clay for president.

As the 1832 election approached, the debate over the re-authorization of the national bank emerged as the most important issue in the campaign. By the early 1830s, the national bank had become the largest corporation in the United States, and

banknotes

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commer ...

issued by the national bank served as the de facto legal tender of the United States. Jackson disliked the national bank because of a hatred of both banks and paper currency. The bank's charter did not expire until 1836, but bank president

Nicholas Biddle asked for renewal in 1831, hoping that election year pressure and support from Secretary of the Treasury

Louis McLane

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, Delaware, Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of t ...

would convince Jackson to allow the re-charter. Biddle's application set off the "

Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its repl ...

"; Congress passed a bill to renew the national bank's charter, but Jackson vetoed it, holding the bank to be unconstitutional. Clay had initially hoped that the national bank re-charter would work to his advantage, but Jackson's allies seized on the issue, redefining the 1832 election as a choice between the president and a "monied oligarchy." Ultimately, Clay was unable to defeat a popular sitting president. Jackson won 219 of the 286 electoral votes and 54.2% of the popular vote, carrying almost every state outside of New England.

Nullification Crisis

The high rates of the

Tariff of 1828 and the

Tariff of 1832 angered many Southerners because they resulted in higher prices for imported goods. After the 1832 election, South Carolina held a state convention that declared the tariff rates of 1828 and 1832 to be nullified within the state, and further declared that federal collection of import duties would be illegal after January 1833. In response to this

Nullification Crisis, Jackson issued his

Proclamation to the People of South Carolina

The Proclamation to the People of South Carolina was written by Edward Livingston and issued by Andrew Jackson on December 10, 1832. Written at the height of the Nullification Crisis, the proclamation directly responds to the Ordinance of Nulli ...

, which strongly denied the right of states to nullify federal laws or

secede. He asked Congress to pass what became known as the

Force Bill, which would authorize the president to send federal soldiers against South Carolina if it sought to nullify federal law.

Though Clay favored high tariff rates, he found Jackson's strong rhetoric against South Carolina distressing and sought to avoid a crisis that could end in civil war. He proposed a compromise tariff bill that would lower tariff rates, but do so gradually, thereby giving manufacturing interests time to adapt to less protective rates. Clay's compromise tariff won the backing of both manufacturers, who believed they would not receive a better deal, and Calhoun, who sought a way out of the crisis but refused to work with President Jackson's supporters on an alternative tariff bill. Though most members of Clay's own National Republican Party opposed it, the

Tariff of 1833

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

passed both houses of Congress. Jackson simultaneously signed the tariff bill and the Force bill, and South Carolina leaders accepted the new tariff, effectively bringing the crisis to an end. Clay's role in resolving the crisis brought him renewed national stature in the wake of a crushing presidential election defeat, and some began referring to him as the "Great Compromiser."

Formation of the Whig Party

Following the end of the Nullification Crisis in March 1833, Jackson renewed his offensive against the national bank, despite some opposition from within his own Cabinet. Jackson and Secretary of the Treasury

Roger Taney pursued a policy of removing all federal deposits from the national bank and placing them in state-chartered banks known as "

pet banks

Pet banks is a derogatory term for state banks selected by the U.S. Department of Treasury to receive surplus Treasury funds in 1833. Pet banks are sometimes confused with wildcat banks. Although the two are distinct types of institutions that ...

." Because federal law required the president to deposit federal revenue in the national bank so long as it was financially stable, many regarded Jackson's actions as illegal, and Clay led

the passage of a Senate motion

censuring Jackson. Nonetheless, the national bank's federal charter expired in 1836, and though the institution continued to function under a Pennsylvania charter, it never regained the influence it had had at the beginning of Jackson's administration.

The removal of deposits helped unite Jackson's opponents into one party for the first time, as National Republicans, Calhounites, former Democrats, and members of the Anti-Masonic Party coalesced into the

Whig Party. The term "Whig" originated from a speech Clay delivered in 1834, in which he compared opponents of Jackson to the

Whigs, a British political party opposed to

absolute monarchy. Neither the Whigs nor the Democrats were unified geographically or ideologically. However, Whigs tended to favor a stronger legislature, a stronger federal government, a higher tariff, greater spending on infrastructure, re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States, and publicly funded education. Conversely, Democrats tended to favor a stronger president, stronger state governments, lower tariffs,

hard money, and expansionism. Neither party took a strong national stand on slavery. The Whig base of support lay in wealthy businessmen, professionals, the professional class, and large planters, while the Democratic base of support lay in immigrant

Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

and yeomen farmers, but each party appealed across class lines.

Partly due to grief over the death of his daughter, Anne, Clay chose not to run in the

1836 presidential election, and the Whigs were too disorganized to nominate a single candidate. Three Whig candidates ran against Van Buren: General

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

, Senator

Hugh Lawson White

Hugh Lawson White (October 30, 1773April 10, 1840) was an American politician during the first third of the 19th century. After filling in several posts particularly in Tennessee's judiciary and state legislature since 1801, thereunder as a Tenn ...

, and Senator Daniel Webster. By running multiple candidates, the Whigs hoped to force a contingent election in the House of Representatives. Clay personally preferred Webster, but he threw his backing behind Harrison who had the broadest appeal among voters. Clay's decision not to endorse Webster opened a rift between the two Whig party leaders, and Webster would work against Clay in future presidential elections. Despite the presence of multiple Whig candidates, Van Buren won the 1836 election with 50.8 percent of the popular vote and 170 of the 294 electoral votes.

Van Buren administration, 1837–1841

Van Buren's presidency was affected badly by the

Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

, a major recession that badly damaged the Democratic Party. Clay and other Whigs argued that Jackson's policies, including the use of pet banks, had encouraged speculation and caused the panic. He promoted the American System as a means for economic recovery, but President Van Buren's response focused on the practice of "strict economy and frugality." As the

1840 presidential election approached, many expected that the Whigs would win control of the presidency due to the ongoing economic crisis. Clay initially viewed Webster as his strongest rival, but Clay, Harrison, and General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

emerged as the principal candidates at the

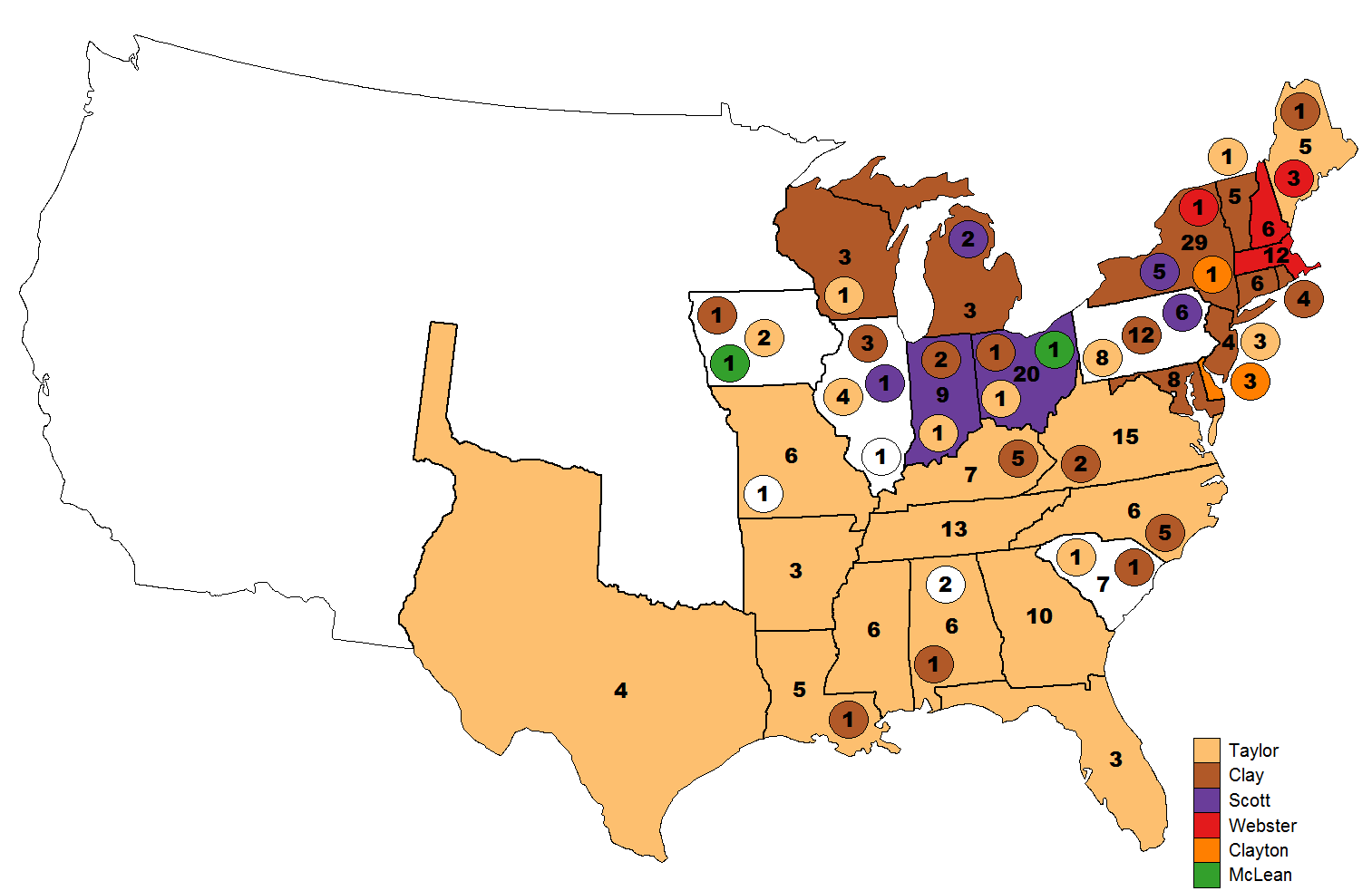

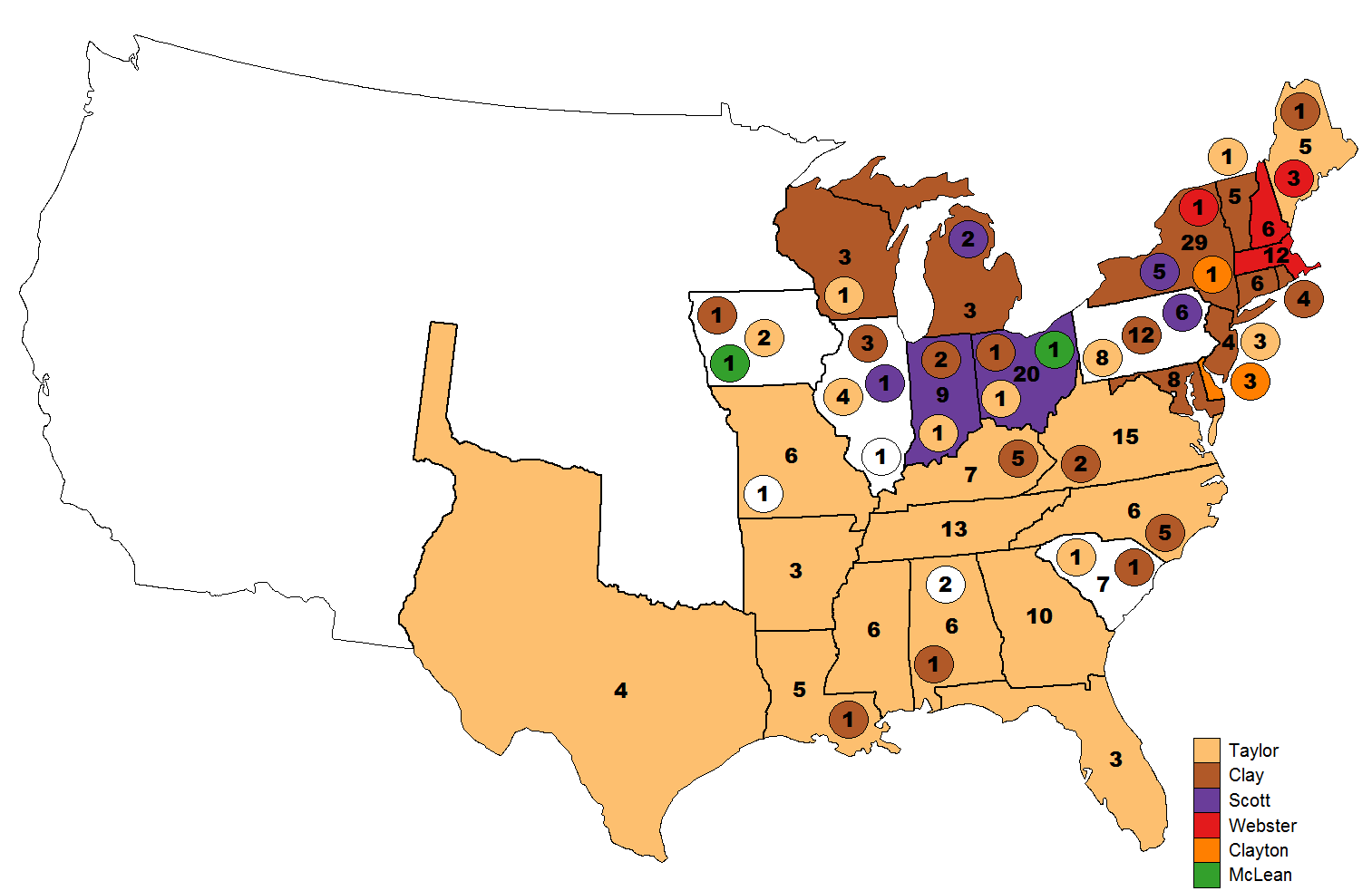

1839 Whig National Convention.

Though he was widely regarded as the most qualified Whig leader to serve as president, many Whigs questioned Clay's electability after two presidential election defeats. He also faced opposition in the North due to his ownership of enslaved people and lingering association with the Freemasons, and in the South from Whigs who distrusted his moderate stance on slavery. Clay won a plurality on the first ballot of the Whig National Convention, but, with the help of

Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was an American printer, newspaper publisher, and Whig Party (United States), Whig and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor t ...

and other backers, Harrison consolidated support on subsequent ballots and won the Whig presidential nomination on the fifth ballot of the convention. Seeking to placate Clay's supporters and to balance the ticket geographically, the convention chose former Virginia Governor and Senator

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

, a personal friend of Clay, whose previous career in the Democratic Party had practically come to an end, as the vice-presidential nominee. Clay was disappointed by the outcome but helped Harrison's ultimately successful campaign by delivering numerous speeches. With Whigs also winning control of Congress in the

1840 elections, Clay saw the upcoming

27th Congress as an opportunity for the Whig Party to establish itself as the dominant political party by leading the country out of recession.

Harrison and Tyler administrations, 1841–1845

President-elect Harrison asked Clay to serve another term as Secretary of State, but Clay chose to remain in Congress. Webster was instead chosen as Secretary of State, while