Harold Brown (Secretary of Defense) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

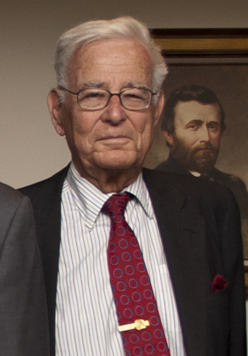

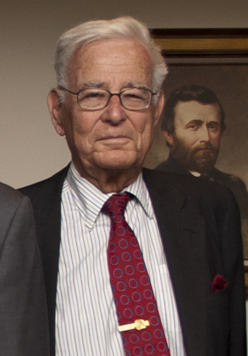

Harold Brown (September 19, 1927 – January 4, 2019) was an American

/ref> As Secretary of Defense, he set the groundwork for the

Although Brown had accumulated almost eight years of prior service in

Although Brown had accumulated almost eight years of prior service in  With regard to strategic planning, Brown shared much the same concerns as his Republican predecessors—the need to upgrade U.S. military forces and improve collective security arrangements—but with a stronger commitment to

With regard to strategic planning, Brown shared much the same concerns as his Republican predecessors—the need to upgrade U.S. military forces and improve collective security arrangements—but with a stronger commitment to

By early 1979, Brown and his staff had developed a "countervailing strategy", an approach to nuclear targeting that past secretaries of defense

By early 1979, Brown and his staff had developed a "countervailing strategy", an approach to nuclear targeting that past secretaries of defense

After leaving the Pentagon, Brown remained in

After leaving the Pentagon, Brown remained in

Annotated Bibliography for Harold Brown from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Air Force biography

* , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Harold 1927 births 2019 deaths 20th-century American politicians American physicists Carter administration cabinet members Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Columbia College (New York) alumni Deaths from pancreatic cancer in California Enrico Fermi Award recipients Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Jewish members of the Cabinet of the United States Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory staff Members of the United States National Academy of Engineering Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Politicians from Brooklyn Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Presidents of the California Institute of Technology Scientists from New York City The Bronx High School of Science alumni United States secretaries of defense United States Secretaries of the Air Force Fellows of the American Physical Society

nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

who served as United States Secretary of Defense

The United States secretary of defense (acronym: SecDef) is the head of the United States Department of Defense (DoD), the United States federal executive departments, executive department of the United States Armed Forces, U.S. Armed Forces, a ...

from 1977 to 1981, under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. Previously, in the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

administrations, he held the posts of Director of Defense Research and Engineering

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

(1961–1965) and United States Secretary of the Air Force

The secretary of the Air Force, sometimes referred to as the secretary of the Department of the Air Force, (SecAF, or SAF/OS) is the head of the United States Department of the Air Force, Department of the Air Force and the service secretary for ...

(1965–1969).

A child prodigy

A child prodigy is, technically, a child under the age of 10 who produces meaningful work in some domain at the level of an adult expert. The term is also applied more broadly to describe young people who are extraordinarily talented in some f ...

, Brown graduated from the Bronx High School of Science

The Bronx High School of Science is a State school, public Specialized high schools in New York City, specialized high school in the Bronx in New York City. It is operated by the New York City Department of Education. Admission to Bronx Science ...

at age 15, and earned a Ph.D. in physics from Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

at age 21.Edward C. Keefer, Harold Brown: Offsetting the Soviet Military Challenge, 1977–1981, 2017, Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense/ref> As Secretary of Defense, he set the groundwork for the

Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retre ...

, took part in strategic arms negotiations with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and supported, unsuccessfully, ratification of the SALT II

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

treaty.

Early life and career

Brown was born inBrooklyn, New York

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, the son of Abraham, a lawyer who had fought in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and Gertrude (Cohen) Brown, a diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

merchant's bookkeeper. His parents were secular Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and strong supporters of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. From a very young age Brown was drawn to mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

; he enrolled as a student at the Bronx High School of Science

The Bronx High School of Science is a State school, public Specialized high schools in New York City, specialized high school in the Bronx in New York City. It is operated by the New York City Department of Education. Admission to Bronx Science ...

, from which he graduated at age 15 with a grade average of 99.5. He then immediately entered Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, earning an A.B. summa cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sout ...

at 17 years of age, as well as the ''Green Memorial Prize'' for the best academic record. He continued as a graduate student at Columbia, and was awarded a Ph.D. in physics in 1949 when he was 21.

After a short period of teaching and postdoctoral research, Brown became a research scientist at the Radiation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

. At Berkeley, he played a role in the construction of the Polaris missile

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fuel rocket, solid-fueled nuclear warhead, nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy ...

and the development of plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

. In 1952, he joined the staff of the University of California Radiation Laboratory at Livermore and became its director in 1960, succeeding Edward Teller

Edward Teller (; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian and American Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of ...

, of whom he was a protégé. At Livermore, Brown led a team of six other physicists, all older than he was, who used some of the first computer

A computer is a machine that can be Computer programming, programmed to automatically Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic set ...

s, along with mathematics and engineering, to reduce the size of thermonuclear warheads for strategic military use. Brown and his team helped make Livermore's reputation by designing nuclear warheads small and light enough to be placed on the Navy's nuclear-powered ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are powered only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles (SRBM) typic ...

submarines ( SSBNs). During the 1950s he served as a member of, or consultant to, several federal scientific bodies and as senior science adviser at the 1958-1959 Conference on the Discontinuance of Nuclear Tests.

Brown worked under United States Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

as Director of Defense Research and Engineering

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

from 1961 to 1965, and then as United States Secretary of the Air Force

The secretary of the Air Force, sometimes referred to as the secretary of the Department of the Air Force, (SecAF, or SAF/OS) is the head of the United States Department of the Air Force, Department of the Air Force and the service secretary for ...

from October 1965 to February 1969, first under McNamara and then under Clark Clifford.

From 1969 to 1977, he was President of the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

(Caltech).

U.S. Secretary of Defense

Appointment and initial agenda

Although Brown had accumulated almost eight years of prior service in

Although Brown had accumulated almost eight years of prior service in the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

, he was the first natural scientist

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

to become secretary of defense. He involved himself in practically all areas of departmental activity. Consistent with the Carter administration's objective to reorganize the federal government, Brown launched a comprehensive review of defense organization that eventually brought significant change. But he understood the limits to effective reform. In one of his first speeches after leaving office, "'Managing' the Defense Department-Why It Can't Be Done," at the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

in March 1981, he observed: With regard to strategic planning, Brown shared much the same concerns as his Republican predecessors—the need to upgrade U.S. military forces and improve collective security arrangements—but with a stronger commitment to

With regard to strategic planning, Brown shared much the same concerns as his Republican predecessors—the need to upgrade U.S. military forces and improve collective security arrangements—but with a stronger commitment to arms control

Arms control is a term for international restrictions upon the development, production, stockpiling, proliferation and usage of small arms, conventional weapons, and weapons of mass destruction. Historically, arms control may apply to melee wea ...

. Brown adhered to the principle of " essential equivalence" in the nuclear competition with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. This meant that "Soviet strategic nuclear forces do not become usable instruments of political leverage, diplomatic coercion, or military advantage; nuclear stability, especially in a crisis, is maintained; any advantages in force characteristics enjoyed by the Soviets are offset by U.S. advantages in other characteristics; and the U.S. posture is not in fact, and is not seen as, inferior in performance to the strategic nuclear forces of the Soviet Union."

His later writings in his 2012 memoir, ''Star-Spangled Security'', reinforced this agenda:When I became secretary of defense in 1977, the military services, most of all the army, were disrupted badly by theAccording to ''Vietnam War The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w .... There was general agreement that the Soviet Union outclassed the West in conventional military capability, especially in ground forces in Europe.

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', experts say in retrospect that contrary to a popular narrative which asserts that President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

increased defense spending to ramp up competition with (and ultimately bankrupting) the Soviet Union, it was Carter and Brown who began "maintaining the strategic balance, countering Soviet aircraft and ballistic innovations by improving land-based ICBMs, by upgrading B-52 strategic bombers with low-flying cruise missiles and by deploying far more submarine-launched missiles tipped with MIRVs, or multiple warheads that split into independent trajectories to hit many targets".

Nuclear missiles

Brown considered it essential to maintain the triad of ICBMs, SLBMs, and strategic bombers; some of the administration's most important decisions on weapon systems reflected this commitment. Although he decided not to produce the B-1 bomber, he did recommend upgrading existing B-52s and equipping them with air-launchedcruise missile

A cruise missile is an unmanned self-propelled guided missile that sustains flight through aerodynamic lift for most of its flight path. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large payload over long distances with high precision. Modern cru ...

s, and gave the go-ahead for development of a "stealth" technology, fostered by William J. Perry, under-secretary of defense for research and engineering, that would make it possible to produce planes (bombers as well as other aircraft) with very low radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

profiles, presumably able to elude enemy defenses and deliver weapons on targets. The administration backed development of the MX missile

The LGM-118 Peacekeeper, originally known as the MX for "Missile, Experimental", was a MIRV-capable intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) produced and deployed by the United States from 1986 to 2005. The missile could carry up to eleven Mar ...

, intended to replace in the 1980s the increasingly vulnerable Minuteman and Titan

Titan most often refers to:

* Titan (moon), the largest moon of Saturn

* Titans, a race of deities in Greek mythology

Titan or Titans may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Fictional entities

Fictional locations

* Titan in fiction, fictiona ...

intercontinental missiles. To insure MX survivability, Brown recommended deploying the missiles in "multiple protective shelters"; 200 MX missiles would be placed in Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

and Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

, with each missile to be shuttled among 23 different shelters of its own located along roadways-meaning a total of 4,600 such shelters. Although this plan was expensive and environmentally controversial, Brown argued that it was the most viable scheme to protect the missiles from enemy attack. For the sea leg of the triad, Brown accelerated development of the larger Trident nuclear submarine and carried forward the conversion of Poseidon submarines to a fully MIRVed missile capability.

By early 1979, Brown and his staff had developed a "countervailing strategy", an approach to nuclear targeting that past secretaries of defense

By early 1979, Brown and his staff had developed a "countervailing strategy", an approach to nuclear targeting that past secretaries of defense Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

and James R. Schlesinger had both earlier found attractive, but never formally codified. As Brown put it, "we must have forces and plans for the use of our strategic nuclear forces such that in considering aggression against our interests, our adversary would recognize that no plausible outcome would represent a success-on any rational definition of success. The prospect of such a failure would then deter an adversary's attack on the United States or our vital interests." Although Brown did not rule out the assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would result in ...

approach, which stressed attacks on urban and industrial targets, he believed that "such destruction must not be automatic, our only choice, or independent of any enemy's attack. Indeed, it is at least conceivable that the mission of assured destruction would not have to be executed at all in the event that deterrence failed."

Official adoption of the countervailing strategy came with President Carter's approval of Presidential Directive 59 (PD 59) on July 25, 1980. In explaining PD 59 Brown argued that it was not a new strategic doctrine, but rather a refinement, a codification of previous explanations of our strategic policy. The heart of PD 59, as Brown described it, was as follows:

Because the almost simultaneous disclosures of PD 59 and the stealth technology came in the midst of the 1980 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 4, 1980. In a landslide victory, the Republican Party (United States), Republican ticket of former California governor Ronald Reagan and form ...

campaign; some critics asserted that the Carter administration leaked them to counter charges of weakness and boost its re-election chances. Others charged that PD 59 made it more likely that the United States would initiate a nuclear conflict, based on the assumption that a nuclear war could somehow be limited. Brown insisted that the countervailing strategy was not a first strike strategy. As he put it, "Nothing in the policy contemplates that nuclear war can be a deliberate instrument of achieving our national security goals. ... But we cannot afford the risk that the Soviet leadership might entertain the illusion that nuclear war could be an option – or its threat a means of coercion – for them."

NATO

Brown regarded the strengthening ofNATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

as a key national security objective and worked hard to invigorate the alliance. With the assistance of Robert W. Komer

Robert William "Blowtorch Bob" Komer (February 23, 1922 – April 9, 2000) was an American national security adviser known for managing Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support during the Vietnam War.

Early life and education

Born ...

, at first his special adviser on NATO affairs and subsequently under-secretary of defense for policy, Brown launched a series of NATO initiatives shortly after taking office. In May 1978 the NATO heads of government endorsed a long term defense program which included 10 priority categories: enhanced readiness; rapid reinforcement; stronger European reserve forces; improvements in maritime capabilities; integrated air defenses; effective command, control, and communications; electronic warfare; rationalized procedures for armaments collaboration; logistics co-ordination and increased war reserves; and theater nuclear modernization. To implement the last item, NATO defense and foreign ministers decided in December 1979, to respond to the Soviet deployment of new theater nuclear weapons—the SS-20 missile and the Backfire bomber—by placing 108 Pershing II missiles and 464 ground-launched cruise missile

The BGM-109G Gryphon ground-launched cruise missile, or GLCM, was a ground-launched variant of the Tomahawk (missile family), Tomahawk cruise missile developed by the United States Air Force in the last decade of the Cold War and disarmed under ...

s (GLCMs) in several Western European countries beginning in December 1983. The NATO leaders indicated that the new missile deployment would be scaled down if satisfactory progress occurred in arms control negotiations with the Soviet Union.

At Brown's urging, NATO members pledged in 1977 to increase their individual defense spending three percent per year in real terms for the 1979-86 period. The objective, Brown explained, was to ensure that alliance resources and capabilities-both conventional and nuclear-would balance those of the Soviet bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

. Although some NATO members hesitated to confirm the agreement to accept new missiles and did not always attain the three percent target, Brown was pleased with NATO's progress. Midway in his term he told an interviewer that he thought his most important achievement thus far had been the revitalization of NATO.

Brown also tried to strengthen the defense contributions of U.S. allies outside of NATO, particularly Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

and South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

. He repeatedly urged the Japanese government

The Government of Japan is the central government of Japan. It consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and functions under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan. Japan is a unitary state, containing forty- ...

to increase its defense budget so that it could shoulder a larger share of the Western allies' Pacific security burden. Although the Carter administration decided in 1977 on a phased withdrawal of United States ground forces from South Korea, it pledged to continue military and other assistance to that country. Later, because of a substantial buildup of North Korean military forces and opposition to the troop withdrawal in the United States, the president shelved the plan, leaving approximately 40,000 U.S. troops in Korea. In establishing diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(PRC) on January 1, 1979, the United States formally recognized the PRC almost 30 years after its establishment. A year later Brown visited the PRC, talked with its political and military leaders, and helped lay the groundwork for limited collaboration on security issues.

Arms control

Arms control formed an integral part of Brown's national security policy. He staunchly supported the June 1979SALT II

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union and was the administration's leading spokesman in urging the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

to approve it. SALT II limited both sides to 2,250 strategic nuclear delivery vehicles (bombers, ICBMs, SLBMs, and air-to-surface ballistic missiles), including a sublimit of 1,200 launchers of MIRVed ballistic missiles, of which only 820 could be launchers of MIRVed ICBMs. It also placed restrictions on the number of warheads on each missile and on deployment of new land-based ballistic missile systems, except for one new type of light ICBM for each side. There was also a provision for verification by each side using its own national technical means.

Brown explained that SALT II would reduce the Soviet Union's strategic forces, bring enhanced predictability and stability to Soviet-U.S. nuclear relationships, reduce the cost of maintaining a strategic balance, help the United States to monitor Soviet forces, and reduce the risk of nuclear war. He rebutted charges by SALT II critics that the United States had underestimated the Soviet military buildup, that the treaty would weaken the Western alliance, that the Soviet Union could not be trusted to obey the treaty, and that its terms could not really be verified. Partly to placate Senate opponents of the treaty, the Carter administration agreed in the fall of 1979 to support higher increases in the defense budget. However, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

in December 1979 ensured that the Senate would not accept the treaty at that time, forcing the president to withdraw it from consideration. When his term ended in 1981, Brown said that failure to secure ratification of SALT II was his greatest regret. The U.S. and the Soviet Union still followed the terms of the pact, even though it was non-binding, until 1986, when President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

accused the Soviet Union of violating the terms and withdrew from the pact.

Regional matters

Panama Canal

Besides broad national security policy matters, Brown had to deal with several more immediate questions, among them thePanama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

issue. Control of the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

had been a source of contention ever since Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

achieved its independence from Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

in 1903 and granted the United States a concession "in perpetuity".

In the mid-1960s, after serious disturbances in the zone, the United States and Panama began negotiations that went on intermittently until September 7, 1977, when the countries signed two treaties, one providing for full Panamanian control of the canal by the year 2000 and the other guaranteeing the canal's neutrality. The Defense Department played a major role in the Panama negotiations. Brown championed the treaties through a difficult fight to gain Senate approval (secured in March and April 1978), insisting that they were both advantageous to the United States and essential to the canal's future operation and security.

Middle East

InMiddle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

affairs, Brown supported President Carter's efforts as an intermediary in the Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

ian-Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

i negotiations leading to the Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retre ...

of September 1978 and the signing by the two nations of a peace treaty in March 1979. Elsewhere, the fall of the Shah

Shāh (; ) is a royal title meaning "king" in the Persian language.Yarshater, Ehsa, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII, no. 1 (1989) Though chiefly associated with the monarchs of Iran, it was also used to refer to the leaders of numerous Per ...

from power in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

in January 1979 eliminated a major U.S. ally and triggered a chain of events that played havoc with American policy in the region. In November 1979, Iranian revolutionaries occupied the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took more than 50 hostages. Brown participated closely in planning for a rescue operation that ended in failure and the loss of eight U.S. servicemen on April 24–25, 1980. Not until the last day of his administration, on January 20, 1981, could President Carter make final arrangements for the release of the hostages.

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

TheSoviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

in December 1979 to bolster a pro-Soviet Communist government further complicated the role of the United States in the Middle East and Southwest Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenia ...

. In response to the events in Iran and Afghanistan and in anticipation of others, Brown activated the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force

The Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) is an inactive United States Department of Defense Joint Task Force. It was first envisioned as a three- division force in 1979 as the Rapid Deployment Force (RDF), a highly mobile rapid deployment ...

(RDJTF) at MacDill Air Force Base

MacDill Air Force Base (MacDill AFB) is an active United States Air Force installation located 4 miles (6.4 km) south-southwest of downtown Tampa, Florida.

The "host wing" for MacDill AFB is the 6th Air Refueling Wing (6 ARW), assig ...

, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, on March 1, 1980. Although normally a planning headquarters without operational units, the RDJTF could obtain such forces from the several services and command them in crisis situations. Brown explained that the RDJTF was responsible for developing plans for contingency operations, particularly in Southwest Asia, and maintaining adequate capabilities and readiness for such missions.

Budget

As with all of his predecessors, budget matters occupied a major portion of Brown's time. During the 1976 campaign, President Carter criticized the defense spending levels of the Ford administration and promised cuts in the range of $5 billion to $7 billion. Shortly after he became secretary, Brown suggested a series of amendments to Ford's proposedfiscal year

A fiscal year (also known as a financial year, or sometimes budget year) is used in government accounting, which varies between countries, and for budget purposes. It is also used for financial reporting by businesses and other organizations. La ...

1978 budget, having the effect of cutting it by almost $3 billion, but still allowing a Total Obligational Authority (TOA) increase of more than $8 billion over the fiscal year 1977 budget. Subsequent budgets under Brown moved generally upward, reflecting high prevailing rates of inflation, the need to strengthen and modernize conventional forces neglected somewhat since the end of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, and serious challenges in the Middle East, Iran, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

The Brown Defense budgets by fiscal year, in TOA, were as follows: 1978, $116.1 billion; 1979, $124.7 billion; 1980, $141.9 billion; and 1981, $175.5 billion. In terms of real growth, there were slight negative percentages in 1978 and 1979, and increases in 1980 and 1981. Part of the increase for fiscal year 1981 resulted from supplemental appropriations obtained by the Reagan administration; but the Carter administration by this time had departed substantially from its early emphasis on curtailing the department of defense budget. Its proposals for fiscal year 1982, submitted in January 1981, called for significant real growth over the TOA for fiscal year 1981.

In his 2012 memoir, ''Star-Spangled Security'', Brown boasted that "the Defense Department budget in real terms was 10 to 12 percent more when we left than when we came in", which he opined was not an easy accomplishment, especially considering Carter's campaign promise to cut defense spending, and pressure to that effect from congressional Democrats. With the increased budget, Brown oversaw the development of "stealth" aircraft, and the acceleration of "the Trident submarine program and the conversion of older Poseidon submarines to carry MIRVs".

Departure

Brown left office on January 20, 1981, following President Carter's unsuccessful bid for re-election. During the 1980 campaign, Brown actively defended the Carter administration's policies, speaking frequently on national issues in public. Brown received thePresidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

from President Carter in 1981 and the Enrico Fermi Award

The Enrico Fermi Award is a scientific award conferred by the President of the United States. It is awarded to honor scientists of international stature for their lifetime achievement in the development, use or production of energy. It was establ ...

from President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

in 1993.

Later life

After leaving the Pentagon, Brown remained in

After leaving the Pentagon, Brown remained in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, joining the Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

School of Advanced International Studies as a visiting professor and later the university's Foreign Policy Institute as chairman. He continued to speak and write widely on national security issues, and in 1983 published "Thinking About National Security: Defense and Foreign Policy in a Dangerous World"/ In later years, Brown was affiliated with research organizations and served on the boards of a number of corporations, like Altria

Altria Group, Inc. (previously known as Philip Morris Companies, Inc. until 2003) is an American corporation and one of the world's largest producers and marketers of tobacco, cigarettes, and medical products in the treatment of illnesses ca ...

(previously Philip Morris).

Brown was honored with Columbia College’s John Jay Award for distinguished professional achievement in 1980 and Alexander Hamilton Medal in 1990.

On January 5, 2006, he participated in a meeting at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

of former Secretaries of Defense and State to discuss United States foreign policy with Bush administration officials.

In July 2011, Brown became a member of the United States Energy Security

Energy security is the association between national security and the availability of natural resources for energy consumption (as opposed to household energy insecurity). Access to cheaper energy has become essential to the functioning of modern ...

Council, which seeks to diminish oil's monopoly over the U.S. transportation sector and is sponsored by the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security (IAGS).

Brown died of pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of ...

on January 4, 2019, at the age of 91.

See also

*Harold Brown Award

The Harold Brown Award is the highest award given by the United States Air Force to a scientist or engineer who applies scientific research to solve a problem critical to the needs of the Air Force.

History and purpose

The Harold Brown Award is i ...

* Membership discrimination in California social clubs

* Aspin–Brown Commission

*List of Jewish United States Cabinet members

The Cabinet of the United States, which is the principal advisory body to the President of the United States, has had 47 American Jews, Jewish American members altogether. Of that number, 27 different Jewish American individuals held a total of ...

References

Further reading

*Keefer, Edward C. ''Harold Brown: Offsetting the Soviet Military Challenge, 1977—1981'' (Washington: Historical Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2017), xxii, 815 pp.External links

Annotated Bibliography for Harold Brown from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Air Force biography

* , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Harold 1927 births 2019 deaths 20th-century American politicians American physicists Carter administration cabinet members Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Columbia College (New York) alumni Deaths from pancreatic cancer in California Enrico Fermi Award recipients Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Jewish members of the Cabinet of the United States Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory staff Members of the United States National Academy of Engineering Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Politicians from Brooklyn Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Presidents of the California Institute of Technology Scientists from New York City The Bronx High School of Science alumni United States secretaries of defense United States Secretaries of the Air Force Fellows of the American Physical Society