Hiram Wesley Evans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hiram Wesley Evans (September 26, 1881 – September 14, 1966) was an American dentist and political activist who served as the Imperial Wizard of the

In the early years of Evans's tenure, the Klan reached record enrollment; estimates of its peak range from 2.5 to 6 million members, but records are poor and the figure cannot be accurately determined. He also dramatically increased the organization's total assets, more than doubling them from July 1922 to July 1923. Evans changed the way that chapter leaders were paid by insisting that they receive a fixed salary, rather than commissions based on membership fees, in a move that lowered their income. Although previous Imperial Wizards had lived in lavish properties, Evans initially settled into an apartment after his promotion. The sociologist Rory McVeigh of the

In the early years of Evans's tenure, the Klan reached record enrollment; estimates of its peak range from 2.5 to 6 million members, but records are poor and the figure cannot be accurately determined. He also dramatically increased the organization's total assets, more than doubling them from July 1922 to July 1923. Evans changed the way that chapter leaders were paid by insisting that they receive a fixed salary, rather than commissions based on membership fees, in a move that lowered their income. Although previous Imperial Wizards had lived in lavish properties, Evans initially settled into an apartment after his promotion. The sociologist Rory McVeigh of the

Although the Klan had four million members in 1924, the group's membership quickly shrank after Stephenson's widely publicized trial. The Indiana Klan lost more than 90% of its members by the end of the proceedings, and there were mass resignations in other states as well. Other scandals emerged, further damaging Klan enrollment. Although the Colorado Klan had seen strong growth, Evans asked the Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke, to resign after local corruption scandals in 1925 involving Klan members who served as police. Evans's request was poorly received by Colorado Klan members, and local enrollment subsequently plummeted.

He encountered difficulties with Klan leaders in Pennsylvania in 1926 after many of them concluded that he was too autocratic. In response, he revoked the charters of several local Klan groups and removed John Strayer, a state legislator, from his position of authority in the Klan. When the Pennsylvania groups continued to refer to themselves as the Ku Klux Klan, Evans sued them in federal court. Pennsylvania Klan members launched a detailed legal offensive against Evans and other Klan leaders, alleging misdeeds, including participation in kidnappings and lynchings. Evans's suit was unsuccessful and, as many newspapers reported the scandalous allegations aired in court, the Pennsylvania Klan suffered a serious decline in membership and support.

In response to the decline in Klan membership, Evans organized a Klan parade in 1926 in Washington, D.C., hoping that a large turnout would demonstrate the Klan's power. About 30,000 members attended, making it the largest parade in the group's history. Evans was disappointed, however, as he had expected twice as many people, and the march did not stanch the drop in membership. That year, Evans attempted to rally U.S. senators to vote against a bill supporting a proposed world court. He was unsuccessful, however, and several Klan-backed senators followed Coolidge and supported the bill. In 1928, Evans opposed the candidacy of the New York Democratic governor

Although the Klan had four million members in 1924, the group's membership quickly shrank after Stephenson's widely publicized trial. The Indiana Klan lost more than 90% of its members by the end of the proceedings, and there were mass resignations in other states as well. Other scandals emerged, further damaging Klan enrollment. Although the Colorado Klan had seen strong growth, Evans asked the Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke, to resign after local corruption scandals in 1925 involving Klan members who served as police. Evans's request was poorly received by Colorado Klan members, and local enrollment subsequently plummeted.

He encountered difficulties with Klan leaders in Pennsylvania in 1926 after many of them concluded that he was too autocratic. In response, he revoked the charters of several local Klan groups and removed John Strayer, a state legislator, from his position of authority in the Klan. When the Pennsylvania groups continued to refer to themselves as the Ku Klux Klan, Evans sued them in federal court. Pennsylvania Klan members launched a detailed legal offensive against Evans and other Klan leaders, alleging misdeeds, including participation in kidnappings and lynchings. Evans's suit was unsuccessful and, as many newspapers reported the scandalous allegations aired in court, the Pennsylvania Klan suffered a serious decline in membership and support.

In response to the decline in Klan membership, Evans organized a Klan parade in 1926 in Washington, D.C., hoping that a large turnout would demonstrate the Klan's power. About 30,000 members attended, making it the largest parade in the group's history. Evans was disappointed, however, as he had expected twice as many people, and the march did not stanch the drop in membership. That year, Evans attempted to rally U.S. senators to vote against a bill supporting a proposed world court. He was unsuccessful, however, and several Klan-backed senators followed Coolidge and supported the bill. In 1928, Evans opposed the candidacy of the New York Democratic governor

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

, an American white supremacist

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

group, from 1922 to his resignation in 1939.

A native of Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, Evans attended Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private university, private research university in Nashville, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provide ...

studying dentistry

Dentistry, also known as dental medicine and oral medicine, is the branch of medicine focused on the Human tooth, teeth, gums, and Human mouth, mouth. It consists of the study, diagnosis, prevention, management, and treatment of diseases, dis ...

. He operated a small, moderately successful practice in Texas until 1920, when he joined the Klan's Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

chapter. He quickly rose through the ranks and was part of a group that ousted William Joseph Simmons from the position of Imperial Wizard, the national leader, in November 1922. Evans succeeded him and sought to transform the group into a political power.

Evans had led the kidnapping and torture of a black man while leader of the Dallas Klan, but as Imperial Wizard, he publicly discouraged vigilante actions for fear that they would hinder his attempts to gain political influence. In 1923, Evans presided over the largest Klan gathering in history, attended by over 200,000, and endorsed several successful candidates in 1924 elections. He moved the Klan's headquarters from Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

to Washington, D.C., and organized a march of 30,000 members, the largest march in the organization's history, on Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C. that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown. Traveling through So ...

. Evans's efforts notwithstanding, the Klan was buffeted by damaging publicity in the early 1920s, partially because of leadership struggles between Evans and his rivals, which hindered his political efforts.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

significantly decreased the Klan's income, prompting Evans to work for a construction company to supplement his pay. He resigned his position with the Klan in 1939, after disavowing anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. Scholars have identified four categories of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cul ...

. He was succeeded by his chief of staff, James A. Colescott. The next year, Evans faced accusations of involvement in a government corruption scandal in Georgia; he was fined $15,000 after legal proceedings.

Evans sought to promote a form of nativist, Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

nationalism. In addition to his white supremacist ideology, he fiercely condemned Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

ism, and communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, which he associated with recent immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. He argued that Jews formed a non-American culture and resisted assimilation although he denied being an anti-Semite

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

. Historians credit Evans with refocusing the Klan on political activities and recruiting outside the South; the Klan grew most in the Midwest and industrial cities but this political influence and membership gains he sought were transitory.

Early life and education

Evans was born inAshland, Alabama

Ashland is a city in and the county seat of Clay County, Alabama, United States. The population was 2,037 at the 2010 census.

History

Clay County was formed by an act of the Alabama General Assembly on December 7, 1866. Less than a year late ...

, on September 26, 1881, and moved to Hubbard, Texas, with his family as a child. The son of Hiram Martin Evans, a judge, and his wife, Georgia Evans, the younger Evans graduated from Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private university, private research university in Nashville, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provide ...

. Shortly after, he became a dentist, receiving his license in 1900. He married Ellen "Bama" Hill in 1923; they had three children together.

Evans established a small, moderately successful dentistry practice in Downtown Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

that provided inexpensive services. Rumors later arose that his dental qualifications were "a bit shady." A Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, Evans attended a church belonging to the Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

denomination. He was also a Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

. Evans described himself as "the most average man in America." Of average height and somewhat overweight, Evans was well dressed, a skilled speaker, and very ambitious.

Initial Klan activities

Conceived by its founders as a continuation of theReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

-era Klan (controversially linked to General Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was an List of slave traders of the United States, American slave trader, active in the lower Mississippi River valley, who served as a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Con ...

), the revived Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

had been established in Atlanta in 1915. Leading up to his involvement in the Klan, Evans had a significant personal involvement in Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

. He was initially raised in ''Dallas Lodge No. 760'' in July 1907 under the Grand Lodge of Texas. Evans was involved in both York Rite

In Anglo-American Freemasonry, York Rite, sometimes referred to as the American Rite, is one of several Rites of Freemasonry. It is named after York, in Yorkshire, England, where the Rite was supposedly first practiced.

A Rite is a series of ...

(including the Masonic "Knights Templar") and Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry is a List of Masonic rites, rite within the broader context of Freemasonry. It is the most widely practiced List of Masonic rites, Rite in the world. In some parts of the world, and in the ...

freemasonry. Evans was raised to the Thirty-Second Degree at the Dallas Consistory in April 1913. He was also a member of the Shriners

Shriners International, formally known as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (AAONMS), is an American Masonic body, Masonic society. Founded in 1872 in New York City, it is headquartered in Tampa, Florida, and has over ...

, having joined the ''Hella Temple'' at Dallas in April 1911. Within the York Rite, Evans was a Past Master of ''Pentagon Lodge No. 1080'' in Dallas. Bertram G. Christie, the founder of the Dallas Klan in 1920, was also a mason and met with Evans and a few of his fellow masons belonging to the Pentagon Lodge in March 1921, such as George K. Butcher.

The following month, Evans was involved in his first Klan vigilante activity when he took part in the flogging and branding of Alex Johnson on April 1, 1921. According to a contemporary report in the '' Denton Record-Chronicle'', Johnson was a "Negro bus boy" who was being investigated by the police after he had been discovered in the room of a white woman guest at the hotel.

Evans left his dental practice so that he could dedicate all his time to the group. In 1921, he was elected as "exalted cyclops", a recruiting position sometimes referred to as kleagle, in the Dallas Klan No. 66. When he was elected, the Dallas Klan had recently received a "self-ruling charter" from the Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

-based leadership and was the group's largest chapter. The same year, Evans was appointed to the position of "great titan" (executive) of the "Realm of Texas" and proceeded to lead a successful membership drive for the state's Klan.

Evans initially supported violence against minorities, remembering a lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of i ...

he witnessed as a child. With the Texas Klan, he sought to create "black squads" to attack minorities. He joined several Klan members in kidnapping and torturing a black bellhop, ostensibly because they suspected he was involved in pandering prostitutes. Atlanta-based leaders pressured Evans to curb racial violence in Dallas; around then, the Texas Klan had received significant negative publicity after castrating an African-American doctor. Although Evans was not morally opposed to violence against minorities, he publicly condemned vigilante activity because he feared that it would attract government scrutiny and hinder potential Klan-backed political campaigning. The change of stance led the leader of the Houston Klan to accuse him of hypocrisy. Although Evans later took credit for a decrease in lynchings in the Southern United States during the 1920s, several Klan members claimed that he surreptitiously encouraged and presided over acts of violence against minorities.

In 1921, Evans was assigned to oversee the Klan's national membership drive at the behest of their publicists, Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke. In 1922, the group's leadership made Evans the "Imperial kligrapp", a role similar to national secretary, in which capacity he oversaw operations in 13 states. He received a base salary of $7,500 and traveled throughout the country, regularly meeting with local Klan leaders.

Early national leadership

In 1922, Evans joined a group of Klan activists, including Tyler, Clarke, and D. C. Stephenson, in a "coup" against William Joseph Simmons, the group's leader. They deceived Simmons into agreeing to a reorganization of the Klan that removed his practical control; Simmons said that they had claimed that if he remained the Imperial Wizard of the Klan, discord would hamper the organization. Evans gained power and was formally ensconced as Imperial Wizard of the Klan at a November 1922 "Klonvokation" in Atlanta, Georgia. Although a legal battle between Evans and Simmons ensued, during which time Simmons was the Klan's titular "emperor," Evans retained control of the Klan. He initially said that he had been unaware of a pending coup until after he was selected. However, by the end of their feud, he described Simmons as the "leader ofBolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

Klansmen betraying the movement" and later expelled the former leader.

As the leader of the Klan, Evans advanced a form of nativist, white supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

that cast Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

as a fundamental part of American patriotism. To Evans, whiteness and Protestantism were equally valued and sometimes conflated: he said the Klan supported the "uncontaminated growth of Anglo-Saxon civilization". He maintained the belief that white Protestants had the exclusive right to govern the US because they were the descendants of the early colonists, whom he described as fleeing Europe for the US to escape its societal bounds. He admitted that many Klan members were of rural, uneducated backgrounds but argued that power should be given to "the common people of America." In a pamphlet entitled ''Ideals of the Ku Klux Klan'', Evans described the Klan as follows:

# This is a white man's organization.

# This is a gentile organization.

# It is an American organization.

# It is a Protestant organization.

Under Evans, the Klan supported a mixture of right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

and left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

political positions, which were described by Thomas Pegram of Loyola University Maryland

Loyola University Maryland is a Private university, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit university in Baltimore, Maryland. Established as Loyola College in Maryland by John Early (educator), John Early and eight other members of the Society of Je ...

as "too much of a patchwork to be considered an ideological system." Klan literature spoke highly of politicians such as Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, and Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

. Evans borrowed numerous concepts from the writings of Lothrop Stoddard and Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservation movement, conservationist, eugenics, eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant i ...

, American writers of the period who promoted eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

and scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, and he attempted to cast his platforms as if they were based on science. Evans attacked immigrants by arguing that they would promote ideologies such as anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

and communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, were threats to national unity, and were involved with bootlegging during Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

. He considered immigrants "ignorant, superstitious, religious devotees" intent on earning money in the US before retiring to their homelands. However, he supported immigration of whom he deemed "Nordic."

Evans also argued against miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is marriage or admixture between people who are members of different races or ethnicities. It has occurred many times throughout history, in many places. It has occasionally been controversial or illegal. Adjectives describin ...

, and Catholic and Jewish immigration on the grounds that they were threats to genetic "good stock," a racial division that was widely supported among white Americans. Evans believed the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

sought to take control of the US government; he also questioned American Catholics' loyalty to their country, writing that they were subject to their priests, and, as such, to the entire Roman Catholic hierarchy and the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. In other writings, he expressed fears that the Catholic Church, in alliance with Jews and non-white Protestant groups, was becoming increasingly active in politics and thus blurring the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

.

Under Evans's leadership, the Klan became active in Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, rather than focusing on the Southeast, as it had done in the past. It also grew in Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

, where 40,000 members, more than half its total, lived in Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

. It became characterized as an organization prominent in urban areas of the Midwest, where it attracted native-born Americans competing for industrial jobs with recent immigrants. It also attracted members in Nebraska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington.

Evans appointed Stephenson, his early collaborator, as kleagle and Grand Dragon of Indiana. The relationship between the two leaders quickly became acrimonious; Stephenson clashed with Evans over the distribution of membership fees and became embittered after Evans refused to help fund the purchase of a school in Indiana. Although Stephenson believed Evans had deliberately thwarted his attempt to purchase the school to limit his power, Evans unexpectedly promoted Stephenson to Grand Dragon of the "northern realm" in July 1923.

Historian Leonard Joseph Moore of McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

contends that Evans paid particular attention to the Indiana Klan out of financial self-interest since it was the largest state branch.

The political scientist Arnold S. Rice writes that Evans also worked on a series of changes, advertised as reforms, to the Klan structure and sought to promote a positive public opinion of the Klan; Evans felt that his organization should be able to reach out to those who were "struggling with the moral decay and economic distress of the 20th century." He increased the Klan's surveillance of members before and after initiation, expelling those considered to be of "questionable morals." He also worked to increase Klan involvement in local policing and denounced acts of violence committed by Klan members, promoting the Klan as a symbol of lawfulness. Those efforts, although successful in reducing the number of attacks, were ultimately unable to sway public opinion in the Klan's favor.

Internal conflicts

Evans became embroiled in several internal Klan conflicts that gained media exposure. In January 1921, he and a group of grand dragons expelled the publicist Clarke, who had been critical of Evans's efforts to involve the Klan in electoral politics. Evans also clashed with Henry Grady, a judge fromNorth Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

who served in the Klan from 1922 to 1927, reaching the rank of Grand Dragon. Before Evans gained control of the Klan, Grady had been considered a potential successor to Simmons. After Grady dismissed a Klan-backed law that would have banned the Knights of Columbus

The Knights of Columbus (K of C) is a global Catholic Church, Catholic Fraternal and service organizations, fraternal service order founded by Michael J. McGivney, Blessed Michael J. McGivney. Membership is limited to practicing Catholic men. ...

, a Catholic fraternal service organization, Evans revoked his membership. Grady subsequently leaked his correspondence with Evans to the media.

In August 1923, Evans participated in a Klan parade in the heavily-Catholic borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

of Carnegie, Pennsylvania, which was attacked by local residents. One member of the Klan, Thomas Rankin Abbott, was killed; Evans declared him a martyr and hoped that the death would inspire new recruits. The incident gave a fillip to the Klan's recruitment efforts but increased Stephenson's animosity toward Evans, whom he blamed for the incident. Stephenson's proclivity for ostentation irritated Evans. Although Stephenson left his official Klan position after a short tenure, the Klan's northern supporters, under his leadership, had begun to rival those in the South. He had been a skilled campaigner and demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

, and he remained a well-known advocate of the Klan's platforms after resigning. Evans avoided publicly clashing with him, fearing that it would hurt the candidacies of Klan-backed politicians since Stephenson was closely involved in the successful gubernatorial candidacy of Indiana Klan-member Edward L. Jackson, and the Klan members had significant electoral gains in that state in 1924, including the election of several candidates to the state legislature. After those victories, Stephenson showed further disdain for Evans.

Although membership in the Klan was limited to men, Simmons, after losing control of the national organization, attempted to create a parallel white supremacist organization for women. Evans established a women's group and sued him. Evans won the lawsuit, leading to a public war of words with Simmons, whose lawyer was soon murdered by Evans's press agent; Evans denied complicity. In 1924, Evans paid Simmons $145,000 for a promise to abandon the latter's claim to Klan leadership.

Then, Evans moved the Klan's national headquarters to Washington, D.C., where the murder of Simmon's lawyer had received less publicity. To Evans's consternation, Stephenson also formed a women's auxiliary group. Evans and Stephenson subsequently exchanged allegations of sexual impropriety. Police charged Stephenson with the kidnapping, rape, and murder of a young woman; he maintained that the charges were orchestrated by Evans. After a sensational trial, Stephenson was convicted of second-degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction. ("The killing of another person without justification or excus ...

and given a life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life imprisonment are c ...

; the publicity about the leader's behavior caused thousands of members to abandon the Klan.

Klan growth and political activism

In the early years of Evans's tenure, the Klan reached record enrollment; estimates of its peak range from 2.5 to 6 million members, but records are poor and the figure cannot be accurately determined. He also dramatically increased the organization's total assets, more than doubling them from July 1922 to July 1923. Evans changed the way that chapter leaders were paid by insisting that they receive a fixed salary, rather than commissions based on membership fees, in a move that lowered their income. Although previous Imperial Wizards had lived in lavish properties, Evans initially settled into an apartment after his promotion. The sociologist Rory McVeigh of the

In the early years of Evans's tenure, the Klan reached record enrollment; estimates of its peak range from 2.5 to 6 million members, but records are poor and the figure cannot be accurately determined. He also dramatically increased the organization's total assets, more than doubling them from July 1922 to July 1923. Evans changed the way that chapter leaders were paid by insisting that they receive a fixed salary, rather than commissions based on membership fees, in a move that lowered their income. Although previous Imperial Wizards had lived in lavish properties, Evans initially settled into an apartment after his promotion. The sociologist Rory McVeigh of the University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac (known simply as Notre Dame; ; ND) is a Private university, private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, United States. Founded in 1842 by members of the Congregation of Holy Cross, a Cathol ...

argues that the increase in membership was owing to the Klan's exploitation of a "favorable political context," particularly since native-born white-settler Americans were fearful after increased immigration caused them to compete for jobs and housing in many cities. Evans had high hopes for the Klan, saying in 1923 that he aimed to reach 10 million members. That year, he spoke at the largest Klan gathering in history, a Fourth of July

Independence Day, known colloquially as the Fourth of July, is a federal holiday in the United States which commemorates the ratification of the Declaration of Independence by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing th ...

meeting in rural Indiana that was attended by over 200,000.

Evans sought to include more members from the Southwest in leadership; previously, the Klan had been led by people from the Southeast. In 1922, Evans supported the successful U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

candidacy of Texas Democrat Earle Bradford Mayfield, an event that demonstrated that Klan-supported candidates could win prominent offices. The next year, Evans returned to Texas for the state fair, where 75,000 people gathered for a "Klan day" celebration. He devoted funds to fighting Jack C. Walton, the anti-Klan governor of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

; to the group's joy, Walton was impeached and removed from office in 1923. However, the Oklahoma legislature soon passed several anti-Klan bills.

Evans published instructions for local Klan leaders that detailed how to run meetings, recruit new members, and speak to local gatherings. He advised leaders to avoid "raving hysterically" in favor of " scientific... presentation of facts." In addition, he urged them to forbid members from bringing their Klan regalia home from meetings and to perform background checks on applicants. He instructed Klan members to shun vigilantism but to assist police and attempted, with some success, to recruit police officers into the Klan. Emphasizing the difference between his organization and the more violent 19th-century Ku Klux Klan, Evans formed Klan-themed groups for children. As the Klan attempted to portray itself as a movement led by cultured, well-educated people, its leaders spoke about education in the US. Evans believed that public schools could create a homogeneous society and saw education advocacy as an effective form of public relations.

In his writings on the subject, he cited the nation's illiteracy rate as evidence that American public schools were failing, and he considered low teacher salaries and child labor key obstacles to reform. He supported the idea of a federal Department of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

, hoping that it would lead to improvements in public schools that would help "Americanize the foreigners" and thwart recruitment efforts of Catholic schools. Evans wrote four books in the mid to late 1920s: ''The Menace of Modern Immigration'' (1923), ''The Klan of Tomorrow'' (1924), ''Alienism in the Democracy'' (1927), and ''The Rising Storm'' (1929).

After the Klan gained respect and political influence in parts of the US, Evans hoped to replicate this on a national scale. Political involvement was controversial among the organization's members, and Evans issued contradictory statements on the issue, publicly disavowing it but surreptitiously attempting to sway politicians. Apart from fundamental Klan issues, different local groups often held varying political ideologies; as such, by insisting on specific political stances, Evans would have risked alienating members. Although many of his hopes were never realized, Evans saw several Klansmen elected to high offices and, in the mid-1920s, the group was frequently discussed by political commentators.

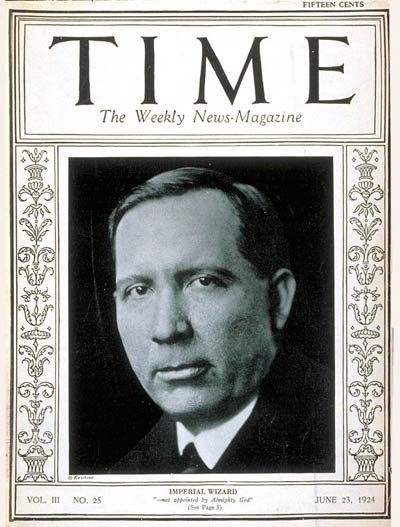

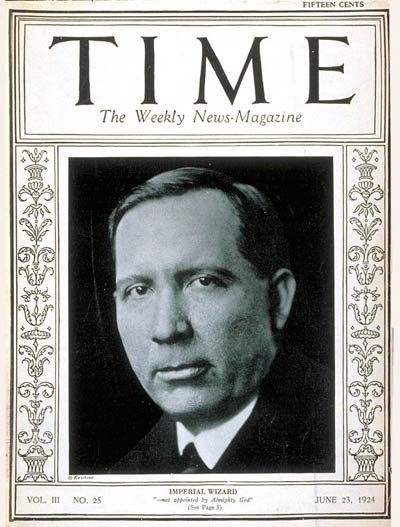

In 1924, the group convinced Republican Party leaders to avoid criticizing it, prompting ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' to put Evans on its cover. That year, the Klan supported Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

in his successful candidacy for president of the U.S. Although Coolidge opposed many key Klan platforms, with the exception of immigration restrictions and prohibition, he was the only major-party candidate who did not condemn them. Nonetheless, Evans declared Coolidge's victory a great success for the Klan. Although Republican leaders refrained from attacking the Klan, they were hesitant to support candidates promoted by the group. Significant discussion of the Klan also took place at the Democratic Party's convention; senator and Democratic presidential primary candidate Oscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood (May 6, 1862 – January 25, 1929) was an United States of America, American lawyer and politician from Alabama, and also a candidate for President of the United States in 1912 and 1924. He was the first formally designa ...

, who finished in fifth place with less than 4% of the delegates, decried them as "a national menace." Evans's attempts to elect Klansmen to public offices in 1924 saw limited success except in Indiana.

Decline of Klan

Although the Klan had four million members in 1924, the group's membership quickly shrank after Stephenson's widely publicized trial. The Indiana Klan lost more than 90% of its members by the end of the proceedings, and there were mass resignations in other states as well. Other scandals emerged, further damaging Klan enrollment. Although the Colorado Klan had seen strong growth, Evans asked the Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke, to resign after local corruption scandals in 1925 involving Klan members who served as police. Evans's request was poorly received by Colorado Klan members, and local enrollment subsequently plummeted.

He encountered difficulties with Klan leaders in Pennsylvania in 1926 after many of them concluded that he was too autocratic. In response, he revoked the charters of several local Klan groups and removed John Strayer, a state legislator, from his position of authority in the Klan. When the Pennsylvania groups continued to refer to themselves as the Ku Klux Klan, Evans sued them in federal court. Pennsylvania Klan members launched a detailed legal offensive against Evans and other Klan leaders, alleging misdeeds, including participation in kidnappings and lynchings. Evans's suit was unsuccessful and, as many newspapers reported the scandalous allegations aired in court, the Pennsylvania Klan suffered a serious decline in membership and support.

In response to the decline in Klan membership, Evans organized a Klan parade in 1926 in Washington, D.C., hoping that a large turnout would demonstrate the Klan's power. About 30,000 members attended, making it the largest parade in the group's history. Evans was disappointed, however, as he had expected twice as many people, and the march did not stanch the drop in membership. That year, Evans attempted to rally U.S. senators to vote against a bill supporting a proposed world court. He was unsuccessful, however, and several Klan-backed senators followed Coolidge and supported the bill. In 1928, Evans opposed the candidacy of the New York Democratic governor

Although the Klan had four million members in 1924, the group's membership quickly shrank after Stephenson's widely publicized trial. The Indiana Klan lost more than 90% of its members by the end of the proceedings, and there were mass resignations in other states as well. Other scandals emerged, further damaging Klan enrollment. Although the Colorado Klan had seen strong growth, Evans asked the Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke, to resign after local corruption scandals in 1925 involving Klan members who served as police. Evans's request was poorly received by Colorado Klan members, and local enrollment subsequently plummeted.

He encountered difficulties with Klan leaders in Pennsylvania in 1926 after many of them concluded that he was too autocratic. In response, he revoked the charters of several local Klan groups and removed John Strayer, a state legislator, from his position of authority in the Klan. When the Pennsylvania groups continued to refer to themselves as the Ku Klux Klan, Evans sued them in federal court. Pennsylvania Klan members launched a detailed legal offensive against Evans and other Klan leaders, alleging misdeeds, including participation in kidnappings and lynchings. Evans's suit was unsuccessful and, as many newspapers reported the scandalous allegations aired in court, the Pennsylvania Klan suffered a serious decline in membership and support.

In response to the decline in Klan membership, Evans organized a Klan parade in 1926 in Washington, D.C., hoping that a large turnout would demonstrate the Klan's power. About 30,000 members attended, making it the largest parade in the group's history. Evans was disappointed, however, as he had expected twice as many people, and the march did not stanch the drop in membership. That year, Evans attempted to rally U.S. senators to vote against a bill supporting a proposed world court. He was unsuccessful, however, and several Klan-backed senators followed Coolidge and supported the bill. In 1928, Evans opposed the candidacy of the New York Democratic governor Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was the 42nd governor of New York, serving from 1919 to 1920 and again from 1923 to 1928. He was the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party's presidential nominee in the 1 ...

for president and emphasized the threat of Smith's Catholic faith. After the Republican Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

won the election, Evans boldly claimed responsibility for Smith's loss, but most of the solidly-Democratic South had rejected Hoover and voted for Smith against the Klan's advice.

In 1929, Evans acknowledged that membership levels had declined but inaccurately predicted a dramatic turnaround would soon occur. The loss of members resulted in a Klan that was a skeleton of its former self. Historians have attributed this loss of membership to ineptness and hypocrisy on the part of Klan leadership. McVeigh argues that the Klan's inability to form alliances with other political groups led to the sharp loss of political power and solidarity within the group.

Changes in focus

Although many Democratic Klan members initially supported the 1932 presidential campaign ofFranklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, the Klan later officially turned against him because of his acceptance of endorsements from minorities and labor unions. After Roosevelt's election, Evans fiercely opposed the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

, describing it as a "great danger" to the nation, and argued that it was a "Jewish" policy that endangered American freedom, reserving particular scorn for Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., who was Jewish. Evans's statements about Jews were sometimes contradictory: he argued that he was not an anti-Semite

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

but maintained that Jews were materialistic and resisted assimilation. The Klan subsequently launched an offensive against organized labor

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

. In the 1930s, Evans fiercely condemned communism and unionism and began to suspect that government agencies had been infiltrated by communists. He focused his attacks on the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of Labor unions in the United States, unions that organized workers in industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in ...

, claiming that they sought to "flout law and promote social disorder."

Although Evans bemoaned commercialism

Commercialism is the application of both manufacturing and consumption towards personal usage, or the practices, methods, aims, and distribution of products in a free market geared toward generating a profit. Commercialism can also refer, positi ...

and attributed it to the effects of liberalism, he supported capitalism and sought to form ties between business leaders and the Klan. He condemned corporate greed, alleging that wealthy elites' desire for cheap labor led to increased immigration. In his view, corporations had changed the Eastern US so that it no longer reflected "true Americanism," a concept that he believed could be understood only by "legitimate Americans" such as himself. He blamed an influx of unskilled laborers for lowering wages in the U.S. Evans believed that immigration policy should restrict the immigration of unskilled workers except for those needed on farms.

In 1934, Evans encountered public controversy after it was revealed that he intended to travel to Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

to campaign against the Democratic governor Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "The Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a United States senator from 1932 until his assassination i ...

, who planned to run in the 1936 presidential election. Long learned of Evans's plans and condemned him in a speech at the Louisiana State Legislature

The Louisiana State Legislature (; ) is the state legislature (United States), state legislature of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is a bicameral legislature, body, comprising the lower house, the Louisiana House of Representatives with 105 ...

, deriding him as a "tooth-puller" and an "Imperial bastard" and warning of grave consequences should he follow through with his plans. After learning of the potential opposition, Evans cancelled his plans but retorted that Long, who based his campaign on Americanist themes, was "un-American."

Downfall and death

In the 1930s, the Klan's public support greatly diminished and their membership dropped to about 100,000 people, primarily concentrated in the South, having lost most of their members elsewhere. James A. Colescott, Evans's handpicked chief of staff, then increasingly shouldered Evans's responsibilities. After theGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

further damaged the Klan's finances, the group's leadership sold their Atlanta headquarters in 1936. Around then, Evans announced his intention to retire.

Although anti-Catholicism had been a consistent platform of the Klan, before leaving the organization, Evans renounced his anti-Catholicism and pronounced a "new era of religious tolerance." In 1939, he said that "in no other time in history has there been more need for all people who believe in the same Father and same Son to stand together." That year, Evans also publicly expressed an interest in learning aspects of Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

to understand the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

better. Chester L. Quarles, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (Epithet, byname Ole Miss) is a Public university, public research university in University, near Oxford, Mississippi, United States, with a University of Mississippi Medical Center, medical center in Jackson, Miss ...

, argues that Evans repudiated anti-Catholicism because of his desire to fight unions and communism and his fear of having too many enemies at one time.

After Evans sold the Klan's former headquarters, it was purchased by the Catholic Church. The Cathedral of Christ the King was later built on the site. Evans attended the building's dedication and spoke highly of the service, surprising many observers. His attendance at the service was his last significant public appearance as Imperial Wizard: he stepped down soon afterwards, having become deeply unpopular with members of the Klan, who felt that he had embraced their enemies. He resigned on June 10, 1939, and was replaced as Imperial Wizard by Colescott.

Evans's service as Imperial Wizard proved to be a lucrative position, allowing him to maintain a large residence in a prestigious Atlanta neighborhood. In the mid-1930s, however, Klan funds dwindled, and he worked for a Georgia-based construction company selling products to the Georgia Highway Board. At the same time, he was a staunch supporter of Georgia Governor Eurith D. Rivers, a liberal pro-New Deal Democrat whom he had previously employed as a lecturer. The political support that he provided the administration allowed Evans to sell to the highway board without bidding against other contractors. In 1940, the state of Georgia charged Evans and a member of the state highway board with price fixing

Price fixing is an anticompetitive agreement between participants on the same side in a market to buy or sell a product, service, or commodity only at a fixed price, or maintain the market conditions such that the price is maintained at a given ...

. The Attorney General of Georgia, Ellis Arnall, directed legal proceedings against Evans that resulted in a $15,000 fine.

Meanwhile, Colescott attempted to resuscitate the waning second Klan by an "administration of action" and stricter enforcement of the Klan's stated policies and led extensive recruitment campaigns. Despite concerns by opponents that the Klan would regain full force after the conclusion of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, it was unable to improve its membership and was under pressure from the Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

for failure to pay taxes. Through a decree on April 23, 1944, Colescott formally disbanded the Klan. Locally-sponsored groups continued to use the name but lacked the united leadership of the earlier Klan.

As late as 1949, Evans served as a commentator on Klan activities, speaking as the former Imperial Wizard. He died on September 14, 1966, in Atlanta.

Appraisal

David A. Horowitz, a historian atPortland State University

Portland State University (PSU) is a public research university in Portland, Oregon, United States. It was founded in 1946 as a post-secondary educational institution for World War II veterans. It evolved into a four-year college over the next ...

, credits Evans with changing the Klan "from a confederation of local vigilantes into a centralized and powerful political movement." Fellow historian William D. Jenkins of Youngstown State University

Youngstown State University (YSU or Youngstown State) is a public university in Youngstown, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1908 and is the easternmost member of the University System of Ohio.

The university is composed of six undergrad ...

maintains that Evans was "personally corrupt and more interested in money or power than a cause." During Evans's tenure as Imperial Wizard, the ''New York Times'' characterized the Klan's leadership as "shrewd schemers". However, Rice suggests that Evans's reforms would never have been successful, as the Klan remained a white supremacist organization that "automatically made enemies of ... anyone who happened to be foreign-born, Negro, Catholic, Jewish, or opposed to bigotry and chauvinism."

An editorial in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' during Evans's tenure as Klan leader described him as "severe and logical" in his writing, but the historian Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter (August 6, 1916October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century. Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier historic ...

described Evans's writings as not immoderate in tone. The communications specialist Nicolas Rangel Jr. of the University of Houston–Downtown suggests that the vernacular prevented some Americans from recognizing the extremist nature of Evans's views.

Evans's ideology was attacked by numerous contemporaries; these criticisms began early in his Klan career. David Lefkowitz, rabbi of Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, assailed Evans's assertion that Jews did not assimilate, emphasizing American experiences shared by Jews and Christians, such as military service in World War I. James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871June 26, 1938) was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ...

, leader of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, responded to Evans's promotion of white supremacy by contending that "all races are mixed." Other well-known adversaries of Evans included the minister and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of Ameri ...

, who opposed the Klan in Detroit in 1925, describing them as "one of the worst specific social phenomena which the religious pride of a people has ever developed." ''The Dallas Morning News

''The Dallas Morning News'' is a daily newspaper serving the Dallas–Fort Worth area of Texas, with an average print circulation in 2022 of 65,369. It was founded on October 1, 1885, by Alfred Horatio Belo as a satellite publication of the ' ...

'' publisher George Dealey and Atlanta journalist Ralph McGill

Ralph Emerson McGill (February 5, 1898 – February 3, 1969) was an American journalist and editorialist. An anti-segregationist editor, he published the ''Atlanta Constitution'' newspaper. He was a member of the Peabody Awards Board of Ju ...

opposed him, the latter deriding him for his hypocrisy and false claims about minorities.

Several publications, however, gave positive coverage to Evans but not necessarily his work with the Klan. In 1927, ''The New York Times'' congratulated Evans on his "modest and engaging exposition of 'Americanism. Although the Klan disowned Evans for reaching out to the Catholic Church, popular opinion was more positive. In 1939, the ''Palm Beach Daily News

The ''Palm Beach Daily News'' is a newspaper serving the town of Palm Beach in Palm Beach County in South Florida. It is also known as "The Shiny Sheet" because of its heavy, slick newsprint stock.

History

The newspaper was founded in 1897 ...

'' described the meeting between Evans and Cardinal Dennis Joseph Dougherty as stirring both religious and secular circles; favorable coverage of the meeting was found in several other publications. Dougherty said that he had found Evans "intensely interested in religious subjects" outside Protestantism.

References

Bibliography

Books * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Journals * Government records * * News * * * * * * Web *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Evans, Hiram Wesley 1881 births 1966 deaths 20th-century American writers American Disciples of Christ American Freemasons American kidnappers Leaders of the Ku Klux Klan People from Ashland, Alabama Vanderbilt University alumni People from Hubbard, Texas Texas Democrats American Ku Klux Klan members 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American dentists History of racism in Texas