, also known as , was a prominent Japanese

bacteriologist

A bacteriologist is a microbiologist, or similarly trained professional, in bacteriology— a subdivision of microbiology that studies bacteria, typically Pathogenic bacteria, pathogenic ones. Bacteriologists are interested in studying and learnin ...

at the

Rockefeller Institute known for his work on

syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

,

serology

Serology is the scientific study of Serum (blood), serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the medical diagnosis, diagnostic identification of Antibody, antibodies in the serum. Such antibodies are typically formed in r ...

,

immunology

Immunology is a branch of biology and medicine that covers the study of Immune system, immune systems in all Organism, organisms.

Immunology charts, measures, and contextualizes the Physiology, physiological functioning of the immune system in ...

, and contributing to the long term understanding of

neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis is the infection of the central nervous system by '' Treponema pallidum'', the bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted infection syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics, the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been report ...

.

Before the Rockefeller Institute, he was a research assistant to American physician

Silas Weir Mitchell at the

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

laying the foundation to the fields of immunology and serology.

[Mehl, Margaret (2023). "From Fukushima to Ghana: Noguchi Hideyo, the Peasant Boy Who Made It (2)"] He produced one of the first serums to treat

North American rattlesnake bites alongside

Thorvald Madsen

Thorvald John Marius Madsen (February 18, 1870 in Frederiksberg – April 14, 1957 in Gjorslev) was a Danish physician and bacteriologist. Madsen was the director of Statens Serum Institut from 1910 to 1940.

He was the son of General V. H. O. Ma ...

at the

Statens Serum Institute.

During his research, Noguchi was an early advocate for the wide spread use of

antivenoms in the United States before its mass production. He wrote one of the foundational texts on the topic of venoms in his monograph, ''Snake Venoms: An Investigation of Venomous Snakes with Special Reference to the Phenomena of Their Venoms.

''

Beginning at the Rockefeller Institute, he was the first person in the United States to confirm the causative agent of syphilis, ''

Treponema pallidum

''Treponema pallidum'', formerly known as ''Spirochaeta pallida'', is a Microaerophile, microaerophilic, Gram-negative bacteria, gram-negative, spirochaete bacterium with subspecies that cause the diseases syphilis, bejel (also known as endemic ...

,'' after

Fritz Schaudinn

Fritz Richard Schaudinn (19 September 1871 – 22 June 1906) was a German zoologist.

Born in Röseningken (now in Ozyorsky District) in the Province of Prussia, he co-discovered, with Erich Hoffmann in 1905, the causative agent of syphilis, ' ...

and

Erich Hoffmann

Erich Hoffmann (25 April 1868 – 8 May 1959) was a German dermatologist who was a native of Witzmitz, Pomerania.

He studied medicine at the Berlin Military Academy, and was later a professor at the Universities of Halle and Bonn.

Hoffman ...

first identified it in 1905 .

His most notable achievement was identifying the agent of syphilis in the tissues of patients with

general paresis

General paresis, also known as general paralysis of the insane (GPI), paralytic dementia, or syphilitic paresis is a severe neuropsychiatric disorder, classified as an organic mental disorder, and is caused by late-stage syphilis and the chr ...

and

tabes dorsals, a late stage consequence of

tertiary syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent or tertiary. The primary stage classi ...

, establishing the conclusive link between the physical and mental manifestation of the disease. American educator and psychiatrist

John Clare Whitehorn

John Clare Whitehorn (1894–1974) was an American psychiatric educator during the mid-20th century.

Whitehorn was born in a sod house in Spencer, Nebraska, on the prairie, the son of a farmer and part-time school teacher. He graduated from D ...

considered the discovery an outstanding psychiatric achievement.

Later in his career, Noguchi developed the first serum to give partial immunity to

Rocky mountain spotted fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial disease spread by ticks. It typically begins with a fever and headache, which is followed a few days later with the development of a rash. The rash is generally Petechial rash, made up of small s ...

, a notoriously lethal disease before treatment was discovered.

Noguchi's died from yellow fever during an expedition to Africa in search for the cause of the same disease. Posthumously, his work on yellow fever was overturned. Noguchi mistaking it as a bacteria confusing it for a different tropical disease. Noguchi's claims on discovering the causative agent of

rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") because its victims panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abn ...

,

poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe ...

,

trachoma

Trachoma is an infectious disease caused by bacterium '' Chlamydia trachomatis''. The infection causes a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids. This roughening can lead to pain in the eyes, breakdown of the outer surface or cornea ...

were overturned and his pure

culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

of syphilis could not be reproduced. Although unsuccessful he brought more attention to often neglected obscure tropical diseases.

[Lederer, Susan (March 1985). "Hideyo Noguchi's Luetin Experiment and the Antivivisectionists". ''The History of Science Society''. 76 (1): 34-35. doi:10.1086/353736. ]JSTOR

JSTOR ( ; short for ''Journal Storage'') is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary sources founded in 1994. Originally containing digitized back issues of academic journals, it now encompasses books and other primary source ...

232791. PMID

PubMed is an openly accessible, free database which includes primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of ...

3888912. Except he did prove

Carrions disease and verruca peruana were the same species alongside fellow researcher

Evelyn Tilden continuing his research after his death.

Noguchi was one of the first scientists to gain international acclaim for his scientific contributions from Japan, being nominated several times for a

Nobel prize in medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single ...

between 1913 and 1927. Although, he did not receive the prize. Today, he's most known for being featured on the yen and the

Hideyo Noguchi Africa prize The honors men and women "with outstanding achievements in the fields of medical research and medical services to combat infectious and other diseases in Africa, thus contributing to the health and welfare of the African people and of all humankind ...

given in his honor.

Early life

Born Seisaku Noguchi in the

Inawashiro

is a town located in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. , the town had an estimated population of 13,810 in 5309 households, and a population density of 35 persons per km2. The total area of the town was . It is noted as the birthplace of the famous d ...

in

Fukushima Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region of Honshu. Fukushima Prefecture has a population of 1,771,100 () and has a geographic area of . Fukushima Prefecture borders Miyagi Prefecture and Yamagata Prefecture ...

in 1876 to an impoverished farming family.

His mother Shika worked to maintain the family farm and restore the Noguchi name to the honor it once had. Seisaku being descended from

samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

in the days of his great grandfather.

[Plesset, Isabel (1980). ''Noguchi and his Patrons''. Fairleigh Dickson University Press. p. 14-15.]

Childhood accident

Noguchi was two years old when he was left with his deaf grandmother who had poor eyesight alongside his four year old sister, Inu, while his mother worked in the rice fields.

He fell into an

irori

An ''irori'' (, ) is a traditional Japanese sunken hearth fired with charcoal. Used for heating the home and for cooking food, it is basically a square, stone-lined pit in the floor, equipped with an adjustable pothook – called a ''jiza ...

and suffered burns and developed an infection on his left hand.

Since there were no doctor in Inawashiro, his left hand was unable to receive medical attention and remained useless as the upper joints of the fingers were gone, and the remaining joints had adhered to each other to form a solid clump. His thumb was drawn down to his wrist and had become attached to it.

While Seisaku could no longer become a successful farmer. Shika promised to give her son an education.

Early education

In 1883, Noguchi entered Mitsuwa elementary school. His teacher elementary teacher Kobayashi saw his talent and due to generous contributions from his teacher, Noguchi received surgery for his left hand fifteen years after the accident. was the surgeon that operated on Noguchi's hand at his clinic in

Aizuwakamatsu

is a city in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 118,159 in 50,365 households, and a population density of 310 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

History

The area of present-day Aizuwakamatsu ...

.

Noguchi recovered some functionality of his left hand. Afterwards, Noguchi decided to become a doctor. In 1893, sixteen year old Noguchi apprenticed with the same clinic as the doctor who had performed his surgery.

Japan was undergoing a modernization of its medical system during the

Meji Restoration. In 1872, Japan introduced

medical examination

In a physical examination, medical examination, clinical examination, or medical checkup, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a Disease, medical condition. It generally consists of a series of ...

for doctors, a costly and time consuming process. Although graduates of the

Imperial University, an exclusive and elite college, in Tokyo were exempt from the examinations.

Noguchi was not able to get into the Imperial University because of his peasant class. In 1896, he left for Tokyo to receive formal training and prepare for his examination. After one month, Noguchi passed his written portion, and subsequently passed the clinical examinations at twenty years old.

He worked at the port of Yokohama as a quarantine officer, earning 35 yen a month.

During this period, he indulged in brothels and wine.

In 1898, Noguchi changed his first name to Hideyo after reading a novel by Japanese author

Tsubouchi Shōyō

__NoTOC__

was a Japanese author, critic, playwright, translator, editor, educator, and professor at Waseda University. He has been referred to as a seminal figure in Japanese drama. "Wetmore deals cleanly with Japanese theatre as part of the mo ...

about a college student whose character had the same name as him. The character in the story, Seisaku, was an intelligent medical student but became lazy and ruined his life.

Noguchi received a position at the

Kitasato Research. Although, he was an outsider as one of the few doctors to have not graduated from the Imperial University.

Noguchi's patrons

Dr. Watanabe introduced Noguchi to

Chiwaki Morinosuke founder of the Takayama Dental College (precursor to the

Tokyo Dental College) who made him an apprentice. Both Noguchi and Morinosuke became close friend. Morinosuke felt Noguchi showed great talent.

Noguchi's main benefactors were, Sakae Kobayashi, his elementary school teacher and father figure,

Kanae Watanabe, the doctor who performed surgery on his hand,

and Morinosuke Chiwaki, who helped fund his travel to the United States.

Leaving Japan

Noguchi was inspired to go to the United States. Partly, motivated by difficulties in obtaining a medical position in Japan as it required expensive schooling.

He experienced discrimination as employers were concerned his hand deformity would discourage patients.

In 1899, Noguchi met

Simon Flexner

Simon Flexner (March 25, 1863 – May 2, 1946) was a physician, scientist, administrator, and professor of experimental pathology at the University of Pennsylvania (1899–1903). He served as the first director of the Rockefeller Institute for ...

during his internship as his translator, being one of a few people who spoke English and Japanese at the Kitasato Institute.

Flexner, who was visiting to see research being made on dysentery from foreign scientists, gave polite words of encouragement to his desire to work in the United States.

Noguchi decided that was that and bought a ticket on the ''

America Maru.'' Chiwaki took a loan to pay for it.

' Noguchi hosted a party to celebrate, spending most of his money before leaving.

Early career

On December 30, 1900, Noguchi arrived in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

.

[Plesset, Isabel (1980). ''Noguchi and his Patrons''. Fairleigh Dickson University Press. p. 72.] He surprised Flexner at his position at the University of Pennsylvania. In spite of their brief encounter, Noguchi requested a position but he said the university had no funds. Although, Flexner did want to hire an assistant to investigate snake venoms.

Later in Flexner's diary, he recognized his courage and persistence for traveling so far from his home country. The day after he arrived, Flexner asked, "Have you ever studied snake venom?"

While not having much experience, but an abundance of determination, he said, "Yes, sir, I do know a little about it, but I'd like the chance to learn more."

Research at University of Pennsylvania

On January 4, 1901, Noguchi started his research position, earning eight dollars a month, coming straight out of Flexner's pocket.

Flexner left for San Francisco to investigate an outbreak of the plague, leaving Noguchi for three months under the guidance of Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell.

Despite his lack of knowledge, Flexner returned to find he had written a 250 pages on snake venom.

Flexner was impressed.

In addition, Mitchell and Noguchi wrote a joint research paper, which was his first official publication.

Both presented their scientific findings before the

National Academy of Science in Philadelphia, one of the greatest honors an American scientist could have at the time.

Dr. Mitchell spoke during the presentation but Noguchi handled the specimens.

Dr. Mitchell said after their research concluded...

"It is thanks to the great efforts of this young man that I have been able to bring my thirty years of research to their final conclusion."

Although, Dr. Mitchell was concerned about his acceptance into larger Western society.

During his research on snakes, Noguchi complained about live rabbits being fed to snakes in cages and felt the practice cruel, but colleagues said he was too sensitive. Nonetheless, Mitchell recommended him for the Carnegie Fellowship. Noguchi was accepted and became an official researcher and received funding from both the Carnegie Institute and National Academy of Science.

Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich (; 14 March 1854 – 20 August 1915) was a Nobel Prize-winning German physician and scientist who worked in the fields of hematology, immunology and antimicrobial chemotherapy. Among his foremost achievements were finding a cure fo ...

wrote to congratulate him. On July 9, 1907, the University of Pennsylvania awarded Hideyo Noguchi an

honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

.

On July 19, 1907, he wrote to about the accomplishment,

"Everything is beautiful when it is still in a dream state, but when it becomes a reality it is no longer interesting to me... When one wish comes true, another is born... Now I intend to request a medical degree from the Japanese government."

State institute and advocate for antivenom

French scientist

Albert Calmette

Léon Charles Albert Calmette ForMemRS (; 12 July 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He co-discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, an attenuat ...

was the first to produce an

antitoxin

An antitoxin is an antibody with the ability to neutralize a specific toxin. Antitoxins are produced by certain animals, plants, and bacterium, bacteria in response to toxin exposure. Although they are most effective in neutralizing toxins, the ...

for venomous snake bites in 1895. Mitchell had made attempts to produce a serum for rattlesnakes, but was unsuccessful and encouraged his protege.

Subsequently, Noguchi received an invitation to research at the Statens Serum Institute in Copenhagen.

He wrote several papers with fellow bacteriologist, Thorvald Madsen.

Noguchi brought a hundred grams of dried rattlesnake venom to Copenhagen and with Madsen produced one of the first antiserums to treat North American rattlesnake bites in 1903.

Noguchi was the first to propose the mass production of antivenom in the USA, but not having been realized until

Afrânio do Amaral

Afrânio Pompílio Gastos do Amaral (1 December 1894 in Belém – 29 November 1982 in São Paulo) was a Brazilian herpetologist.

As a youngster, he collected snakes for Augusto Emilio Goeldi (1859-1917). He studied medicine in Salvador, Bah ...

from the

Butantan Institute

The Instituto Butantan () is a Brazilian biologic research center located in Butantã, in the western part of the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Instituto Butantan is a public institution affiliated with the São Paulo State Secretariat of Health ...

and his research contributed to the development of the first North American rattlesnake antivenom in 1927.

[Dixon, Bernard]

"Fame, Failure, and Yellowjack"

, ''Microbe Magazine'' (American Society for Microbiology

The American Society for Microbiology (ASM), originally the Society of American Bacteriologists, is a professional organization for scientists who study viruses, bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa as well as other aspects of microbiology. It wa ...

). May 2004.

Major publications

Between 1905 and 1908, Noguchi produced 28 papers and reports on his work with snake venoms and the routine observations of immunologic relationships, as well as tetanus.

[Plesset, Isabel (1980). ''Noguchi and his Patrons''. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 109.] In 1907, he wrote the chapter on venoms in

William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first Residency (medicine), residency program for speci ...

and

Thomas McCraes Modern Medicine.

In 1909, Noguchi released a comprehensive monograph on snake venom, ''Snake Venoms: An Investigation of Venomous Snakes with Special Reference to the Phenomena of Their Venoms''.

The publication contained drawings and several photographs of specimens.

In the preface, it stated,

“No single work in the English language exists at this time which treats of the facts of zoological, anatomical, physiological, and pathological features of venomous snakes, with particular reference to the properties of their venoms."

In 1904, he returned from Copenhagen. Flexner had offered him a position at the Rockefeller Institute alongside six others members.

[Plesset, Isabel (1980). ''Noguchi and his Patrons''. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 105-106.][Flexner, James Thomas. (1996)]

''Maverick's Progress,'' pp. 51

��52. Noguchi moved to

Lexington Avenue

Lexington Avenue, often colloquially abbreviated as "Lex", is an avenue on the East Side (Manhattan), East Side of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue carries southbound one-way traffic from East 131st Street (Manhattan), 131st Street to Gra ...

in New York City. He was introduced to another medical student Norio Araki, who was roommates with Hideyo Noguchi for three years.

Career at the Rockefeller Institute

In 1905, Treponema pallidum was first identified as the cause of syphilis by Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann.

Flexner put Noguchi onto syphilis research as he selected syphilis as one of the major diseases to focus research on at the institute.

In 1906, Noguchi was the first person in the United States to confirm the

spirochete

A spirochaete () or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (also called Spirochaetes ), which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) Gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or ...

sixty days after its discovery.

Between 1906 to 1915, Noguchi made some of his most long lasting discoveries and scientific contributions to syphilis.

Butyric acid test

When the

Wasserman test

The Wassermann test or Wassermann reaction (WR) is an antibody test for syphilis, named after the bacteriologist August Paul von Wassermann, based on complement fixation. It was the first blood test for syphilis and the first in the nontrepon ...

was announced in 1906, Noguchi began working on refining it as it utilized serum reactions, which he was familiar from the course of his research of snake venom.

Noguchi and J. W. Moore created the butyric acid test for diagnosing syphilis, which used fluid from the spinal column, it was considered valuable tool in the early days of syphilis diagnosis. Physicians reported finding the test more sensitive. During the distribution to hospitals, doctors reported, “Noguchi had prepared for us all the antigen and ambocepter tests that we used. He also spent about two weeks at our laboratory and helped us materially by making many of the tests."

In particular, it was effective at diagnosing neurosyphilis as it detected 90 percent of cases of general paralysis. Although, the test was used less as more refined tests were developed and it was technically demanding and required more specialized expertise.

In 1909, he published twelve papers on syphilis.

In 1910, Noguchi published his manuscript, ''Serum Diagnosis of Syphilis'', his most popular publication, assisting doctors and physicians in the diagnosis and treatment of syphilis.

Controversial pure culture of syphilis

Dr. Flexner told him to focus his efforts on obtaining a pure culture of the spirochete. Flexner wrote in his diary, “Once he was started on a problem he would pursue it to the bitter end." Noguchi set up hundreds of tubes for his cultures and used thousands of microscopic slides in his lab.

In February 1911, Noguchi believed that he had grown a pure culture and wrote to his childhood mentor Kobayashi, “I feel as if I am dancing in heaven." He thought it might eradicate of syphilis.

Although few were able to reproduce his results and his pure culture was considered unreproducible.

In 1934,

Hans Zinsser

Hans Zinsser (November 17, 1878 – September 4, 1940) was an American physician, bacteriologist, and prolific author.

The author of over 200 books and medical articles, he was also a published poet. Some of his verses were published in '' ...

, a personal friend of Noguchi, reluctantly said it had not been successful. It was prone to contamination.

Over the next century, bacteriologists and researchers continued struggled to produce a stable culture.

Presence of ''Treponema pallidum'' in paresis

Wards Island State Hospital, located on an island in the East River, held the New York State Pathologic Institute and was located opposite of the Rockefeller Institute. Staff members at the Rockefeller Institute,

Phoebus Levene

Phoebus Aaron Theodore Levene (25 February 1869 – 6 September 1940) was a Russian-born American biochemist who studied the structure and function of nucleic acids. He characterized the different forms of nucleic acid, DNA from RNA, and foun ...

and

James B. Murphy worked at the Pathologic Institute and were well aware of the issue of paresis and brought this up in conversation with Hideyo Noguchi.

When left untreated between 1911 and 1918 87% of patients suffering from neurosyphilis died and 9% improved with 3.5% seen as remissions. Some researchers held out some hope that understanding the pathophysiology of paresis could lead to a cure for late stage neurosyphilis.

Noguchi decided to remove the doubt and demonstrate the presence of caustive agent in paretic brains. He began collecting samples from spinal cords and brains of paretic patients to determine its relationship to syphilis.

In 1912, Noguchi had collected a total of 200 brains and 12 spinal cords samples from patients in collboration with J. W. Moore, a psychiatrist at Wards Island.

Eventually, he discovered the presence of ''Treponema pallidum'' in the spinal cord of a patient. Consequently, this discovery proved the homogeneity of a mental and physical disease and demonstrated that an organic agent could cause

psychosis

In psychopathology, psychosis is a condition in which a person is unable to distinguish, in their experience of life, between what is and is not real. Examples of psychotic symptoms are delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized or inco ...

.

Noguchi visited his friend and neighbor, Ichiro Hori, after his discovery. His friend reported that he bursted in the middle of the night, dancing and wearing nothing but his underwear, shouting, “I found it! I found it!"

With this discovery, Noguchi's influence went beyond bacteriology. John C. Whiteborn wrote about the history of American psychiatry.

“In the organicist tradition, the outstanding psychiatric achievement as well as the final and conclusive link in the demonstration of the etiologic role of syphilis in general paresis was Noguchi and Moore’s demonstration of the spirochete in the brains of general paretics."

Before his discovery, about 20 percent of the New York State mental hospitals were patients suffering from paresis that led to a patient’s death within five to seven years.

Noguchi allowed for these patients to be diagnosed with syphilis. Noguchi proved that general paresis and tabes dorsalis are late stages of tertiary syphilis of the brain and spinal cords. Noguchi had discovered the delayed effects that could appear ten to twenty years after infection on the nervous system.

In 1925,

Association of American Physicians

The Association of American Physicians (AAP) is an honorary medical society founded in 1885 by the Canadian physician Sir William Osler and six other distinguished physicians of his era for "the advancement of scientific and practical medicine ...

granted him its prized

Kober Medal

The George M. Kober Medal and Lectureship are two different awards by the Association of American Physicians (AAP) in honor of one of its early presidents, George M. Kober. The George M. Kober Lectureship, is an honor given to an AAP member "for o ...

for this discovery.

When interviewed later, Noguchi said,

"All you need is enough test tubes, sufficient money, dedication, and hard work. ... and one more thing, you have got to be able to put up with endless failure."

When compared to a genius, he said, "there was no such thing as genius. There was only the willingness to work three, four, even five times harder than the next man".

Dr. Noguchi's name is remembered in the binomial attached to another spirochete, ''

Leptospira noguchii

''Leptospira noguchii'' is a gram-negative, pathogenic organism named for Japanese bacteriologist Dr. Hideyo Noguchi who named the genus ''Leptospira''.Zuerner, Richard L. "Leptospira." Bergey's Manual of Systemic Bacteriology. 2nd ed. Vol. 4th. ...

''.

Unusual research methods

Noguchi was prolific in his lab results. Flexner described his work as "superhuman". His record for numbers of published papers in a single year was an unheard of nineteen submitted to journals. Noguchi published over 200 paper and gave lecture tours throughout Europe during his career.

Noguchi rarely read extensively before his experimentation. He wanted to learn through his failure.

He report in a letter to his mentor,

"Theories are not to be taught by anybody outside of ourselves. We are the best teachers of the truth — I mean by this that we ought to convince ourselves chiefly by our own experiences and own experiments."

Although, he tended to draw premature conclusions. During a lecture on the transmission of syphilis to rabbits, he had been successful in only one out of thirty-six cases. Noguchi did not label his test tubes, he insisted he had it memorized.

He claimed to have a "special method".

His work station was covered in cigarette butts.

His friend Okumura witnessed Noguchi drank and smoked a great deal, but was stunned at how Noguchi could get along without sleep. He could be irresponsible with his specimens. Once he swallowed solution of jaundice while pipetting a culture.

He washed his mouth out with alcohol but he felt he could have contracted

jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

.

Early in his career, Noguchi's found it difficult for him to accept help as he wanted to ensure he received proper credit for his discoveries. Often washed his own test tubes and grounded his own mixtures which research assistants typically do. He once said, "I can't allow someone who doesn't know exactly what I'm doing here to interfere."

When he met Evelyn Tilden, an English major, in Massachusetts, she was hired as his secretary. Tilden was profoundly impactful to the writing of his research papers. Eventually, Tilden became his apprentice and Noguchi encouraged her to enroll in courses in biology and organic chemistry at Columbia University. Eventually, she received a doctoral degree in 1931 and made a career for herself, becoming professor at the

North Western University

Northwestern University (NU) is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois, United States. Established in 1851 to serve the historic Northwest Territory, it is the oldest chartered university in Illinois.

Chartered by the Illinois ...

.

Personal life

Marriage and relationships

Noguchi secretly married Mary Loretta Dardis on April 10, 1912, whom he met for a single time after he returned from Copenhagen. He did not meet her again for years, "then ran into her on the street, had a rose in his hand, held it up to her."

Both came from a background of poverty. Mary, nicknamed Maize, called her husband, Hidey.

The marriage was kept secret from his family, friends, and boss.

Flexner opposed his marriage to an American. Flexner felt he should marry someone of Japanese descent. Noguchi worried his marriage would put his promotion at risk because she would have to be added to his pension and the taboo of having an

interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different "Race (classification of human beings), races" or Ethnic group#Ethnicity and race, racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United Sta ...

.

Their marriage did become known to the public until his death.

Both of them moved into an apartment at 381 Central Park West.

He would turn the kitchen into a laboratory, leaving bacterial specimens in the refrigerator, have microscopes holding germ cultures on the dinner table, and put test tubes in the oven.

Mary would read often to him at his microscope, whether it was old tales, Tolstoy, or Shakespeare. Mary had to endure his long absences on scientific exhibition.

Noguchi would often be caught at the laboratory at night and people would ask him why he was not at home? His usual reply was, "Home? This is my home." Some people thought he was escaping from his relationship but it is revealed through letters their marriage brought great satisfaction. Mary provided a refuge and inspiration.

Suzanne Kamata has discussed how American women, such as Mary Dardis, have played a large part in the success of their Japanese husbands but have often gone unnoticed due to their nationality. She states "her assistance may have even helped to prolong his life."

Since he was notoriously bad with money, he often got paid in two separate checks, one to hand on to his wife who paid the bills and the other to keep so that he would have something to spend it on. Mary could have stopped him from entering financial ruin.

Hideyo was close friends with his neighbor, Ichiro Hori, a Japanese painter and photographer.

During his studies, Noguchi befriended Hajime Hoshi in the United States.

Later Hoshi returned to Japan and started the successful Hoshi Pharmaceutical Co.

Hoshi used his friendship with Noguchi and his reputation for his pharmaceutical company, which Hoshi offered to compensate him for. Noguchi said to give it to his family in Inawashiro.

Return to Japan

He would write often to his mentor, Kobayashi, who granted him permission to call him "father."

His childhood mentor encouraged Noguchi to return and establish his career in Japan.

In 1912, he told his family that he did not plan to return to Japan.

His mother, Shika, who was notably illiterate, wrote, “Please come home soon, please come home soon, please come home soon, please come home soon.

” She worked as a midwife but did not have much of an income and his family was at risk of losing the Noguchi home. Noguchi began sending money every month to his family.

His mother's health declined. Noguchi sent an unsubtle telegram to Hoshi and asked for enough money to return home. Hoshi was generous and immediately sent him enough to return to Japan Noguchi bought a ticket and sailed to visit her and accept the

Imperial Prize on September 5, 1915.

Noguchi was surrounded at the dock with reporters.

He greeted his mentors Chiwaki and Kobayashi at the Imperial Hotel. Noguchi presented them with golden watches as gifts.

When Noguchi greeted his mother, he showed her a photograph of Mary and she approved.

Noguchi spent another ten whole days with his mother, but returned to the United States, and this would be the last time he would be back in Japan.

In November 1918, his mother Shika died.

Illness and recovery in the Catskills

In 1917, Noguchi's health had declined.

Earlier Noguchi was told he had

enlarged heart from his irregular intense activity after a physical examination. Mary called an ambulance since he refused to go to the hospital and was brought to

Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai, also known as Jabal Musa (), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is one of several locations claimed to be the Mount Sinai (Bible), biblical Mount Sinai, the place where, according to the sacred scriptures of the thre ...

hospital.

He was diagnosed with

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

, a severe case with

perforation

A perforation is a small hole in a thin material or web. There is usually more than one perforation in an organized fashion, where all of the holes collectively are called a ''perforation''. The process of creating perforations is called perfor ...

of his digestive tract.

He claimed it was jaundice after accidentally digesting. His fever worsened and Mary and those around him thought he might die.

Hoshi financially supported him during his treatment.

He made a slow recovery, Noguchi and Mary after seeing an advertisement in a newspaper took a four hour train ride to the

Catskills

The Catskill Mountains, also known as the Catskills, are a physiographic province and subrange of the larger Appalachian Mountains, located in southeastern New York. As a cultural and geographic region, the Catskills are generally defined a ...

. Both of them booked a room at the Glenbrook Hotel in the small hamlet of

Shandaken, which had less than a hundred people. Noguchi felt it reminded him of his hometown in Fukushima.

Noguchi decided to purchase approximately two hectares and build a house in Shandaken, becoming one of the largest landowners in the hamlet.

He bought it with the money he had leftover for his treatment.

The construction was completed around June 15, 1918.

Noguchi built his home alongside the

Esopus river where he would fish and paint and spend most of his summers in 1918, 1922, and 1925 to 1927.

Hobbies

Noguchi was gifted oil paints from Ichiro Hori and he started painting in Shandaken.

He had excellent success. Ichiro said, "he would be good at anything" and was not surprised at his painting ability.

His paintings hang in th

Hideyo Noguchi Memorial Museum

Noguchi was an amateur photographer. It was said that there is no scientific researcher who likes photography more than Noguchi.

He might have been one of the first non hand colored photographs of a Japanese person.

He achieved this through using

autochrome lumière

The Autochrome Lumière was an early color photography process patented in 1903 by the Lumière brothers in France and first marketed in 1907. Autochrome was an additive color "mosaic screen plate" process. It was one of the principal color phot ...

. He sent this in a letter, dated August 8, 1914, to his childhood mentor, Sakae Kobayashi.

Noguchi was fluent in Japanese and English, but also spoke German, Dutch, French, Mandarin, Danish and Spanish.

Luetin experiment and the antivivisectionists

In 1911 and 1912 at the

Rockefeller Institute in New York City, Noguchi was working on a syphilis skin test, which could provide an additional diagnostic procedure to complement the

Wassermann test

The Wassermann test or Wassermann reaction (WR) is an antibody test for syphilis, named after the bacteriologist August Paul von Wassermann, based on complement fixation. It was the first blood test for syphilis and the first in the nontrepon ...

in the detection of syphilis.

Professor

William Henry Welch

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

, Board of Scientific Directors at the

Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, urged Noguchi to conduct human trials.

The subjects were gathered from clinics and hospitals across New York City. In the experiment, the doctors given the tests injected an inactive product of

syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

, called luetin, under the skin on the upper arm of the patient.

Method and Clinical Trials

Skin reactions were studied, as they varied among healthy subjects and syphilis patients, based on the disease's stage and its treatment. The lutein test gave a positive reaction almost 100 percent for

congenital

A birth defect is an abnormal condition that is present at childbirth, birth, regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disability, disabilities that may be physical disability, physical, intellectual disability, intellectual, or dev ...

and late syphilis. While his diagnostic test was effective, it never had a reliable supply from the organism in pure culture form, never yielding practical results.

Of the 571 subjects, 315 had syphilis.

The remaining subjects were controls; some of which were orphans between the ages of 2 and 18 years.

Most were hospital patients being treated for diseases, such as

malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

,

leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a Chronic condition, long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the Peripheral nervous system, nerves, respir ...

,

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, and

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, and the subjects did not realize they were being experimented on and could not give consent.

Public reactions to the experiment

Critics at the time, mainly from the

anti-vivisectionist

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

movement, noted that the

Rockefeller Institute violated the rights of vulnerable orphans and hospital patients. There was concern among anti-vivisectionists that the test subjects had contracted syphilis from the experiments, but were proven to be false.

[Lederer, Susan E. ''Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995/1997 paperback ]

In Dr. Noguchi's defense, Noguchi had performed tests on animals to ensure the safety of the lutein test.

Rockefeller Institute business manager

Jerome D. Greene wrote a letter to the Anti-Vivisection Society, which had pointed out that Noguchi had tested it on himself and his fellow researchers before administering it.

In a letter to District Attorney

Charles S. Whitman

Charles Seymour Whitman (September 29, 1868March 29, 1947) was an American lawyer who served as the 41st governor of New York from January 1, 1915, to December 31, 1918. An attorney and politician, he also served as a delegate from New York to th ...

, Greene said

"What public institution would not welcome a harmless and painless test which would enable it to decide in the case of every person admitted whether that person was afflicted with a venereal disease or not?"

Much of the information came from newspapers, which did not consult medical professionals.

Greene mentioned the steps taken to ensure the sterility.

His explanation was considered a demonstration of the care that doctors were taking in research.

In May 1912, the New York Society for the Prevention for Cruelty to Children asked the New York district attorney to press charges against Noguchi, but he declined. Although, none of subjects were infected with syphilis, the Rockefeller Institute did test on patients without consent.

Even though none of the subjects were injured in the experiment, Hideyo Noguchi had committed a wrong, it was 'a wrong without injury'.

, a physician, social reformer, and advocate for vivisectionist restrictions, said in response to

Jerome D. Greene.

"If insurance could have been given that the luetin test implied no risk of any kind, might not the Rockefeller Institute have secured any number of volunteers by the offer of a gratuity of twenty or thirty dollars as a compensation for any discomfort that might be endured?"

Lack of informed consent

During the period, consent in medical science was by no means customary.

The United States did not develop sufficient consensus about

unethical human experimentation

Unethical human experimentation is human experimentation that violates the principles of medical ethics. Such practices have included denying patients the right to informed consent, using pseudoscientific frameworks such as race science, and tort ...

until the late 20th century, which brought laws about involving

informed consent

Informed consent is an applied ethics principle that a person must have sufficient information and understanding before making decisions about accepting risk. Pertinent information may include risks and benefits of treatments, alternative treatme ...

and the rights of patients to pass.

Noguchi received incredible scrutiny. One of the newspapers described him as "the Oriental admirer of the fruits of Western civilization."

He made a wrong doing with his experiments, not obtaining consent, but he might have received more criticism due to his race and the perpetuated stereotype of

yellow peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror, the Yellow Menace, and the Yellow Specter) is a Racism, racist color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the ...

.

At the same time, notable microbiologists, such as

Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

in 1906 to 1907 operated medical concentration camps in Africa to find a cure for sleeping sickness and blinded patients, and

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

experimented on nine-year-old

Joseph Meister

Joseph Meister (21 February 1876 – 24 June 1940) was the first person to be inoculated against rabies by Louis Pasteur, and likely the first person to be successfully treated for the infection, which has a >99% fatality rate once symptoms ...

without a medical license and was suspected to have lied about conducting animal trials. They received far less scrutiny on their legacy.

Later career

In July, 1914, Flexner made Noguchi a full member of the Institute.

His name and discoveries began to appear regularly in American newspapers.

Noguchi felt compelled to make more discoveries and pressure from his boss Simon Flexner and home country to bring respect and honor to his fellow Japanese.

He wrote in a letter,

"I am almost exhausted and I feel the weight of my situation, because every one working at this Institute is expected by the outsiders to do something. Yet, as you know, we cannot find a new thing every day!"

Successes in tropical diseases

Noguchi began to tackle Rocky mountain spotted fever, similar to another disease

Tsutsugamushi present in Japan, where deaths were common among rice planters and farmers.

Furthermore, he began researching

jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

after two Japanese scientists announced a discovery of a spirochete appearing in the liver of a guinea pig demonstrating jaundice.

In June of 1918, Noguchi became chief investigator on a commission of the

International Health Board

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller ("Seni ...

traveled throughout Central America and South America to conduct research to develop a

vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

for yellow fever.

He once said, "Whether I succeed or not is another matter, but the problem is worth trying." Noguchi dabbled in researching numerous diseases at the same time. He felt one might get results.

In 1921, he was elected as a member of the

American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

. In the meantime, Noguchi published a revision of ''Serum Diagnosis of Syphilis'' with assistance from

Evelyn Tilden in 1922, ''Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis'', which aided in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

In 1923, Noguchi had attempted creating passive and active immunity for Rocky mountain spotted fever.

One of his close assistants died during the research, which he mourned. He supported his assistants widow and children.

He made a breakthrough when he produced the first antiserum for the disease to render partial immunity.

During his time in Peru and Ecuador, between 1925 to 1927, he worked on Carrions disease and verruca peruana, which was widespread in the regions, and proved the infections were due to the same species, ''Bartonella bacilliformis.

''His assistant, Akatsu, noted Noguchi showed discontent in his career even with recent breakthroughs.

Noguchi sometimes lost his temper and scolding his assistants, but outside of the laboratory, Noguchi was a different and more open person. He would invite him to restaurants and speak Japanesesomething he never did at the Rockefeller Institute.

In a letter to Flexner, he wrote,

"Somehow I cannot manage to find enough time to sit quietly and think over things calmly and reflect upon many things and phases in life. I seem to be chasing something all the time, perhaps an acquired habit or rather the lack of poise".

Controversial research on yellow fever

Noguchi decided to focus on yellow fever, which some of his colleagues died researching because of his experience with syphilis and spirochetes.

He thought the disease could have been a spirochete after traveling to

Merida,

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and seeing patients demonstrate symptoms of

Weil's disease, but similar to yellow fever. Noguchi identified it as ''Leptospira icterohemorrhagiae''

and mistakingly declaring it the causative agent of yellow fever.

Other scientists unable to repeat his findings, it was questioned.

During his career, whether yellow fever was a virus or a bacteria was a debated topic with viruses having been discovered in 1892. Noguchi worked much of the next ten years to prove his theory that it was from spir bacteria. He even thought he developed a vaccine against it, unknowingly for Weil's disease.

Following the death of British pathologist Adrian Stokes from yellow fever in September 1927, it became increasingly evident that yellow fever was caused by a virus, not by the bacillus ''Leptospira icteroides'', as Noguchi believed.

He began preparing to travel to

Accra

Accra (; or ''Gaga''; ; Ewe: Gɛ; ) is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , had a population of ...

,

Gold Coast (modern-day

Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

) to study yellow fever and get closer to specimens. Noguchi believed himself immune to yellow fever because of his own vaccine.

West Africa

Feeling his reputation was at stake, Noguchi hastened to

Lagos

Lagos ( ; ), or Lagos City, is a large metropolitan city in southwestern Nigeria. With an upper population estimated above 21 million dwellers, it is the largest city in Nigeria, the most populous urban area on the African continent, and on ...

to carry out research. However, he found the working conditions in Lagos did not suit him. At the invitation of Dr.

William Alexander Young, the young director of the British Medical Research Institute, he moved and made this his base in 1927.

The diaries of Oskar Klotz, another researcher with the Rockefeller Foundation,

describe Noguchi's temper and behavior as erratic and bordering on the paranoid. One reason might be he had untreated syphilis, for which he was diagnosed in 1913, but it could have progressed to neurosyphilis, prone to personality changes.

According to Klotz, Noguchi inoculated huge numbers of monkeys with yellow fever, but failed to keep proper records.

Death

Despite this, Noguchi failed to keep infected mosquitoes in their secure containers. In May 1928, having been unable to find evidence for his theories, Noguchi was set to return to New York after spending six months in Africa, but became sick.

Noguchi boarded to sail home but on May 12 was put ashore at Accra. He taken to a hospital and he died on 21 May.

During his last letters to Mary, he writes

“I spend every moment of every day waiting for a telegram from you. When I am dispirited or tired, you are the one thing that raises my spirits. I am always thinking of you. It is rare that I dream but when I do, it is always of you.”

In a letter home, Young states, "He died suddenly noon Monday. I saw him Sunday afternoon – he smiled – and amongst other things, said, “Are you sure you are quite well?" "Quite." I said, and then he said "I don’t understand." His obituary was featured in ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''.

Doing his autopsy, he was found to have a syphilitic heart. Seven days later, despite exhaustive sterilization of the site, Young himself died of yellow fever.

Legacy

Noguchi was profoundly influential during his lifetime. He brought newfound attention to obscure and

tropical diseases

Tropical diseases are diseases that are prevalent in or unique to tropical and subtropical regions. The diseases are less prevalent in temperate climates, due in part to the occurrence of a cold season, which controls the insect population by for ...

, such as trachoma, affecting a large part of developing countries in Africa, often ignored by western scientists.

Furthermore, Noguchi and Tilden's identification of the

leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a wide array of clinical manifestations caused by protozoal parasites of the Trypanosomatida genus ''Leishmania''. It is generally spread through the bite of Phlebotominae, phlebotomine Sandfly, sandflies, ''Phlebotomus'' an ...

pathogen and proving

Carrion's disease

Carrion's disease is an infectious disease produced by '' Bartonella bacilliformis'' infection.

It is named after Daniel Alcides Carrión.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical symptoms of bartonellosis are pleomorphic and some patients from endem ...

and Oroya fever one of the same. He was applauded for his discovery in South America and had a 2.1 km street in

Guayaquil, Ecuador

Guayaquil (), officially Santiago de Guayaquil, is the largest city in Ecuador and also the nation's economic capital and main port. The city is the capital (political), capital of Guayas Province and the seat of Guayaquil Canton. The city is ...

named after him.

His most famous contribution was his identification of syphilis in the brain tissues of patients with paralysis due to

meningoencephalitis

Meningoencephalitis (; from ; ; and the medical suffix ''-itis'', "inflammation"), also known as herpes meningoencephalitis, is a medical condition that simultaneously resembles both meningitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the mening ...

.

In addition to his lasting contributions to the use of snake venom and serums for Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

In the 21st century, the Nobel Foundation archives were opened for public inspection and research. Noguchi was nominated several times for the

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

: in 1913–1915, 1920, 1921 and 1924–1927.

Posthumous retractions

With the electron microscope, which was invented two years after his passing, some of his discoveries became understood as mistaken.

[SS Kantha.]

Hideyo Noguchi's Research on Yellow Fever (1918–1928) In The Pre-Electron Microscope Era

," ''Kitasato Arch. of Exp. Med.'', 62.1 (1989), pp. 1–9

Some of his research, including his discovery of

polio

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe ...

,

rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") because its victims panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abn ...

, trachoma, and yellow fever's cause were not able to be reproduced. His finding that ''Noguchia granulosis'' causes trachoma was questioned within a year of his death. His identification of ''Leptospira icterohemorrhagiae'' as yellow fever was disproven after

Max Theiler

Max Theiler (30 January 1899 – 11 August 1972) was a South African-American virologist and physician. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1951 for developing a vaccine against yellow fever in 1937, becoming the firs ...

discovery. Furthermore, his rabies pathogen medium to cultivate bacteria was prone to contamination.

A Rockefeller Institute researcher criticized him for being unwilling to issue retractions for his claims, but others said it was more flaws inside the system of peer review at the Institute.

Selected works

* 1904:

''The Action of Snake Venom Upon Cold-blooded Animals.'':::Washington, D.C.:

Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution for Science, also known as Carnegie Science and the Carnegie Institution of Washington, is an organization established to fund and perform scientific research in the United States. This institution is headquartered in Wa ...

.

* 1909:

''Snake Venoms: An Investigation of Venomous Snakes with Special Reference to the Phenomena of Their Venoms.'':::Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution.

* 1911:

''Serum Diagnosis of Syphilis and the Butyric Acid Test for Syphilis.'':::Philadelphia:

J. B. Lippincott.

* 1923:

''Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis: A Manual for Students and Physicians.'':::New York:

P. B. Hoeber.

Honors during Noguchi's lifetime

Noguchi was honored with Japanese and foreign decorations. He received honorary degrees from a number of universities.

Noguchi was self-effacing in his public life, and he often referred to himself as "Funny Noguchi" as noted in Times Magazine. When Noguchi was awarded an honorary doctorate at Yale,

William Lyon Phelps

William Lyon Phelps (January 2, 1865 New Haven, Connecticut – August 21, 1943 New Haven, Connecticut) was an American author, critic and scholar. He taught the first American university course on the modern novel. He had a radio show, wrote ...

observed that the kings of Spain, Denmark and Sweden had conferred awards, but "perhaps he appreciates even more than royal honors the admiration and the gratitude of the people."

[ "Angll Inaugurated at Yale Graduation; New President Takes Office Before a Distinguished Audience of University Men; 784 Degrees are given; Mme. Curie, Sir Robert Jones, Archibald Marshall, J.W. Davis and Others Honored,"](_blank)

''New York Times.'' June 23, 1921.

*

Kyoto Imperial University

, or , is a national research university in Kyoto, Japan. Founded in 1897, it is one of the former Imperial Universities and the second oldest university in Japan.

The university has ten undergraduate faculties, eighteen graduate schools, and t ...

,

Doctor of Medicine

A Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated MD, from the Latin language, Latin ) is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the ''MD'' denotes a professional degree of ph ...

, 1909.

* Knight of the

Order of Dannebrog

The Order of the Dannebrog () is a Danish order of chivalry instituted in 1671 by Christian V. Until 1808, membership in the Order was limited to fifty members of noble or royal rank, who formed a single class known as ''White Knights'' t ...

, 1913 (

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

).

* Commander of the

Order of Isabella the Catholic

The Royal Order of Isabella the Catholic (; Abbreviation, Abbr.: OYC) is a knighthood and one of the three preeminent Order of merit, orders of merit bestowed by the Kingdom of Spain, alongside the Order of Charles III (established in 1771) and ...

, 1913 (

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

).

* Commander of the

Order of the Polar Star

The Royal Order of the Polar Star (Swedish language, Swedish: ''Kungliga Nordstjärneorden''), sometimes translated as the Royal Order of the North Star, is a Swedish order of chivalry created by Frederick I of Sweden, King Frederick I on 23 F ...

, 1914 (

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

).

[Kita, p. 182.]

*

Tokyo Imperial University

The University of Tokyo (, abbreviated as in Japanese and UTokyo in English) is a public university, public research university in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1877 as the nation's first modern university by the merger of several Edo peri ...

,

Doctor of Science

A Doctor of Science (; most commonly abbreviated DSc or ScD) is a science doctorate awarded in a number of countries throughout the world.

Africa

Algeria and Morocco

In Algeria, Morocco, Libya and Tunisia, all universities accredited by the s ...

, 1914.

*

Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* H ...

, 1915.

*

Imperial Award,

Imperial Academy (Japan), 1915.

*

Central University of Ecuador

The Central University of Ecuador () is a national university located in Quito, Ecuador. It is the oldest and largest university in the country, and one of the oldest universities in the Americas. The enrollment at the university is over 10,000 ...

, 1919, (

Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

).

[Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs]

Noguchi & Latin America

/ref>

* National University of San Marcos

The National University of San Marcos (, UNMSM) is a public university, public research university located in Lima, the capital of Peru. In the Americas, it is the first officially established (Privilege (legal ethics), privilege by Charles V, ...

, 1920, (Peru)

* Medicine School of Merida, "Doctor ''Honoris Causa'' en Medicina y Cirugía", 1920 (México)

* John Scott Medal

John Scott Award, created in 1816 as the John Scott Legacy Medal and Premium, is presented to men and women whose inventions improved the "comfort, welfare, and happiness of human kind" in a significant way. "...the John Scott Medal Fund, establish ...

, 1921, (United States)

* University of Guayaquil

The University of Guayaquil ( Spanish: ''Universidad de Guayaquil''), known colloquially as the ''Estatal'' (i.e., "the State niversity), is a public university in Guayaquil, Guayas Province, Ecuador.

Estatal was founded in 1883. It is the ol ...

, 1919, Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

.Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

, 1921, (United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

).Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

of France, 1924[Japanese Wikipedia]

* Senior fifth rank in the order of precedence, Japanese government, 1925

Posthumous honors

Noguchi's remains were returned to the United States and buried in

Noguchi's remains were returned to the United States and buried in Woodlawn Cemetery Woodlawn Cemetery is the name of several cemeteries, including:

Canada

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Saskatoon)

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Nova Scotia)

United States

''(by state then city or town)''

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Ocala, Florida), where Isaac Rice and fa ...

in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City.

In 1928, the Japanese government awarded Noguchi the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star, which represents the second highest of eight classes associated with the award.

In 1979, the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research

Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) is a medical research institute located at the University of Ghana in Accra, Ghana. It was founded in 1979 with funds donated by the Japanese government.

History

The Noguchi Memorial Ins ...

(NMIMR) was founded with funds donated by the Japanese government at the University of Ghana

The University of Ghana is a public university located in Accra, Ghana. It is the oldest public university in the country.

The university was founded in 1948 as the University College of the Gold Coast in the British colony of the Gold Coast ...

in Legon, a suburb north of Accra

Accra (; or ''Gaga''; ; Ewe: Gɛ; ) is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , had a population of ...

.

In 1981, the Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental (National Institute of Mental Health) "Honorio Delgado – Hideyo Noguchi" was founded with founds of the Peruvian Government and the JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) in Lima – Perú.

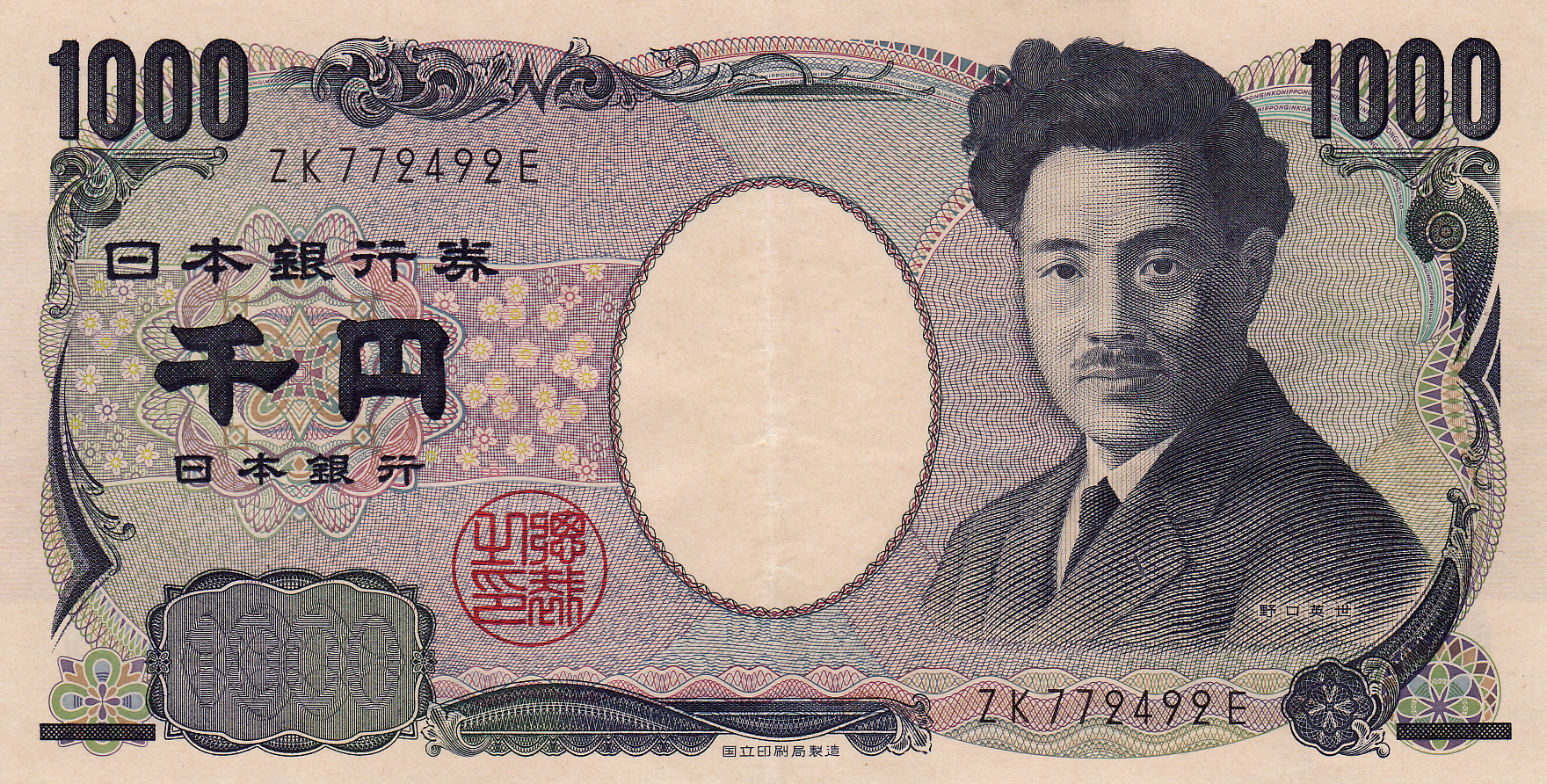

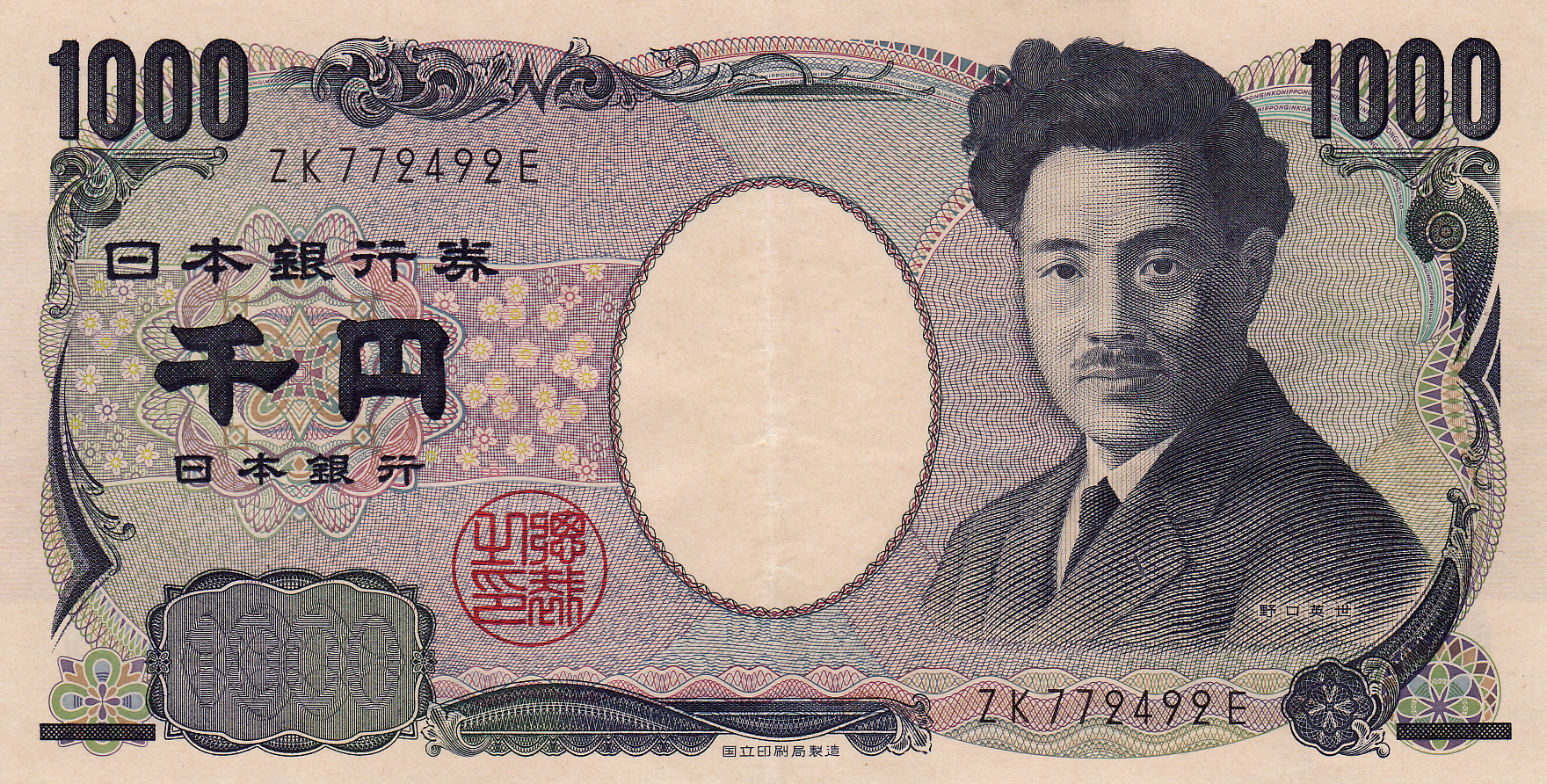

Dr. Noguchi's portrait has been printed on Japanese 1000-yen

The is the official currency of Japan. It is the third-most traded currency in the foreign exchange market, after the United States dollar and the euro. It is also widely used as a third reserve currency after the US dollar and the euro.

T ...

banknotes

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commer ...

since 2004. In addition, the house near Inawashiro where he was born and brought up is preserved. It is operated as part of a museum to his life and achievements.

Noguchi's name is honored at th

Centro de Investigaciones Regionales Dr. Hideyo Noguchi

at the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán

The Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (''Autonomous University of Yucatan''), or UADY, is an autonomous public university in the state of Yucatán, Mexico, with its central campuses located in the state capital of Mérida. It is the largest te ...

.

Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize

The Japanese Government established the

The Japanese Government established the Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize The honors men and women "with outstanding achievements in the fields of medical research and medical services to combat infectious and other diseases in Africa, thus contributing to the health and welfare of the African people and of all humankind ...

in July 2006 as a new international medical research and services award to mark the official visit by Prime Minister Jun'ichirō Koizumi

Junichiro Koizumi ( ; , ''Koizumi Jun'ichirō'' ; born 8 January 1942) is a Japanese retired politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2001 to 2006. He retired from politics in 200 ...

to Africa in May 2006 and the 80th anniversary of Dr. Noguchi's death. The Prize is awarded to individuals with outstanding achievements in combating various infectious diseases in Africa or in establishing innovative medical service systems. The presentation ceremony and laureate lectures coincided with the Fourth Tokyo International Conference on African Development is a conference held regularly with the objective "to promote high-level policy dialogue between African leaders and development partners." Japan is a co-host of these conferences. Other co-organizers of TICAD are the United Nations Office of t ...

in late April 2008. In 2009, the conference venue was moved from Tokyo to Yokohama as another way of honoring the man after whom the prize was named. In 1899, Dr. Noguchi worked at the Yokohama Port Quarantine Office as an assistant quarantine doctor.[Hideyo Noguchi Memorial Museum]

Noguchi, life events

The Prize is expected to be awarded every five years. The prize has been made possible through a combination of government funding and private donations.

''Yomiuri Shimbun'' (Tokyo). March 30, 2008.

See also

*

List of medicine awards

This list of medicine awards is an index to articles about notable awards for contributions to medicine, the science and practice of establishing the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and prevention of disease. The list is organized by region and c ...

*

Max Theiler

Max Theiler (30 January 1899 – 11 August 1972) was a South African-American virologist and physician. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1951 for developing a vaccine against yellow fever in 1937, becoming the firs ...

– completed Noguchi's work, yellow fever vaccine (1926)

*

Human experimentation in the United States

Numerous human subject research, experiments which were performed on human test subjects in the United States in the past are now considered to have been Unethical human experimentation, unethical, because they were performed without the knowled ...

* ''

Tōki Rakujitsu

is a 1992 Japanese film directed by Seijirō Kōyama. It is about the Japanese scientist Hideyo Noguchi. It is based on two biographical novels, ''Tōki Rakujitsu'' written by Junichi Watanabe and ''Noguchi no haha: Noguchi Hideo Monogatari'' w ...

'' – Japanese film

Notes

References

*

*

* D'Amelio, Dan

''Taller Than Bandai Mountain: The Story of Hideyo Noguchi.''New York:

Viking Press

Viking Press (formally Viking Penguin, also listed as Viking Books) is an American publishing company owned by Penguin Random House. It was founded in New York City on March 1, 1925, by Harold K. Guinzburg and George S. Oppenheimer and then acqu ...

. (cloth)

*

* Flexner, James Thomas. (1996)

''Maverick's Progress.''New York:

Fordham University Press

The Fordham University Press is a publishing house, a division of Fordham University, that publishes primarily in the humanities and the social sciences. Fordham University Press was established in 1907 and is headquartered at the university's Li ...

. (cloth)

*

*

* Kita, Atsushi. (2005)

''Dr. Noguchi's Journey: A Life of Medical Search and Discovery''(tr., Peter Durfee). Tokyo:

Kodansha

is a Japanese privately held publishing company headquartered in Bunkyō, Tokyo. Kodansha publishes manga magazines which include ''Nakayoshi'', ''Morning (magazine), Morning'', ''Afternoon (magazine), Afternoon'', ''Evening (magazine), Eveni ...

. (cloth)

*

*

* Lederer, Susan E. ''Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995/1997 paperback

*

*

*

*

*