Hampton Court on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hampton Court Palace is a

General; Ashford, East Bedfont with Hatton, Feltham, Hampton with Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton (1911), pp. 371–379. Retrieved 21 March 2009.) which contained his private rooms (''O on plan''). The Base Court contained forty-four lodgings reserved for guests, while the second court (today, Clock Court) contained the very best rooms the

Henry VIII and his courtiers visited Wolsey at Hampton Court in

Henry VIII and his courtiers visited Wolsey at Hampton Court in  During the Tudor period, the palace was the scene of many historic events. In 1537, the King's much desired male heir, the future

During the Tudor period, the palace was the scene of many historic events. In 1537, the King's much desired male heir, the future

On the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the Tudor period came to an end. The Queen was succeeded by her first cousin-twice-removed, James I of the

On the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the Tudor period came to an end. The Queen was succeeded by her first cousin-twice-removed, James I of the  During this work, half the Tudor palace was replaced and Henry VIII's staterooms and private apartments were both lost; the new wings around the Fountain Court contained new state apartments and private rooms, one set for the King and one for the Queen. Each suite of state rooms was accessed by a state staircase. The royal suites were of completely equal value in order to reflect William and Mary's unique status as joint sovereigns.Williams, p. 54. The King's Apartments face south over the Privy Garden, the Queen's east over the Fountain Garden. The suites are linked by a gallery running the length of the east façade, another reference to Versailles, where the King and Queen's apartments are linked by the

During this work, half the Tudor palace was replaced and Henry VIII's staterooms and private apartments were both lost; the new wings around the Fountain Court contained new state apartments and private rooms, one set for the King and one for the Queen. Each suite of state rooms was accessed by a state staircase. The royal suites were of completely equal value in order to reflect William and Mary's unique status as joint sovereigns.Williams, p. 54. The King's Apartments face south over the Privy Garden, the Queen's east over the Fountain Garden. The suites are linked by a gallery running the length of the east façade, another reference to Versailles, where the King and Queen's apartments are linked by the

On 2 September 1952, the palace was given statutory protection by being

On 2 September 1952, the palace was given statutory protection by being

The palace houses many works of art and furnishings from the

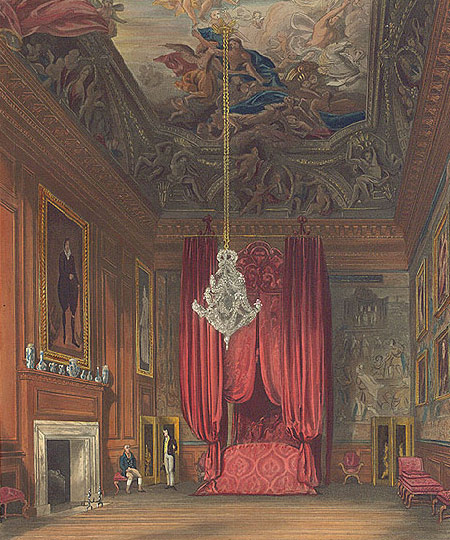

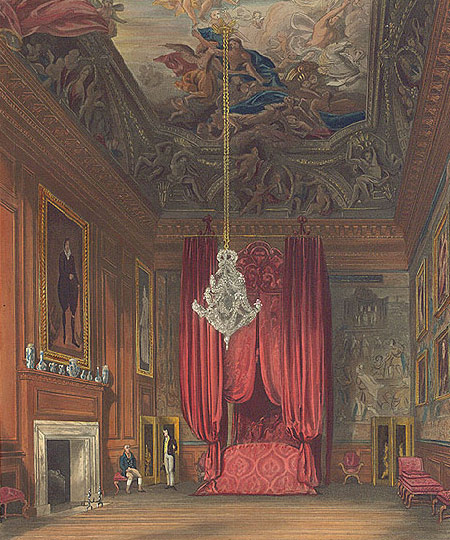

The palace houses many works of art and furnishings from the  Much of the original furniture dates from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, including tables by Jean Pelletier, "India back" walnut chairs by Thomas Roberts and clocks and a barometer by Thomas Tompion. Several state beds are still in their original positions, as is the Throne Canopy in the King's Privy Chamber. This room contains a crystal chandelier of , possibly the first such in the country.

The King's Guard Chamber contains a large quantity of arms: muskets, pistols, swords, daggers, powder horns and pieces of armour arranged on the walls in decorative patterns. Bills exist for payment to a John Harris, dated 1699, for an arrangement believed to be that still seen today.

In addition, Hampton Court holds the majority of the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, with a smaller amount being held at

Much of the original furniture dates from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, including tables by Jean Pelletier, "India back" walnut chairs by Thomas Roberts and clocks and a barometer by Thomas Tompion. Several state beds are still in their original positions, as is the Throne Canopy in the King's Privy Chamber. This room contains a crystal chandelier of , possibly the first such in the country.

The King's Guard Chamber contains a large quantity of arms: muskets, pistols, swords, daggers, powder horns and pieces of armour arranged on the walls in decorative patterns. Bills exist for payment to a John Harris, dated 1699, for an arrangement believed to be that still seen today.

In addition, Hampton Court holds the majority of the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, with a smaller amount being held at

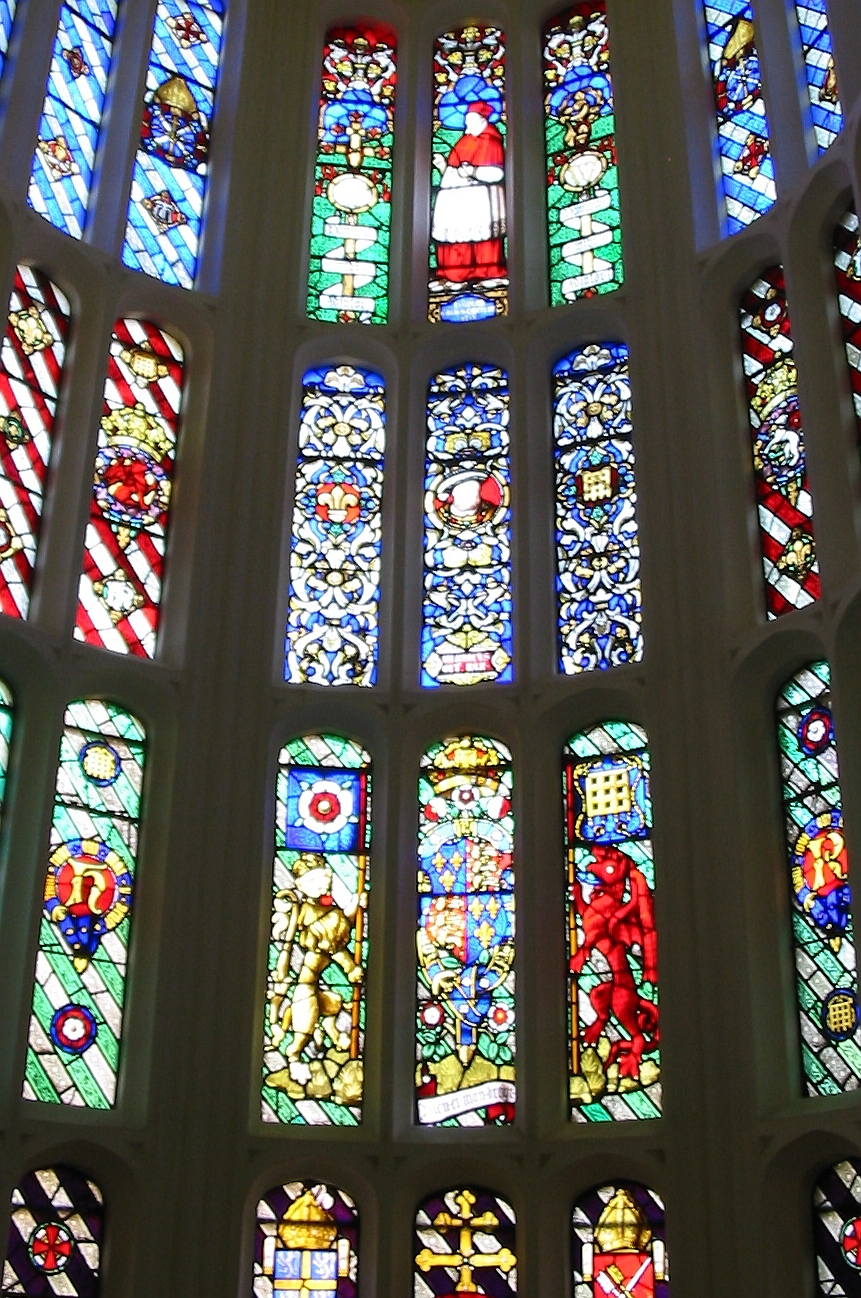

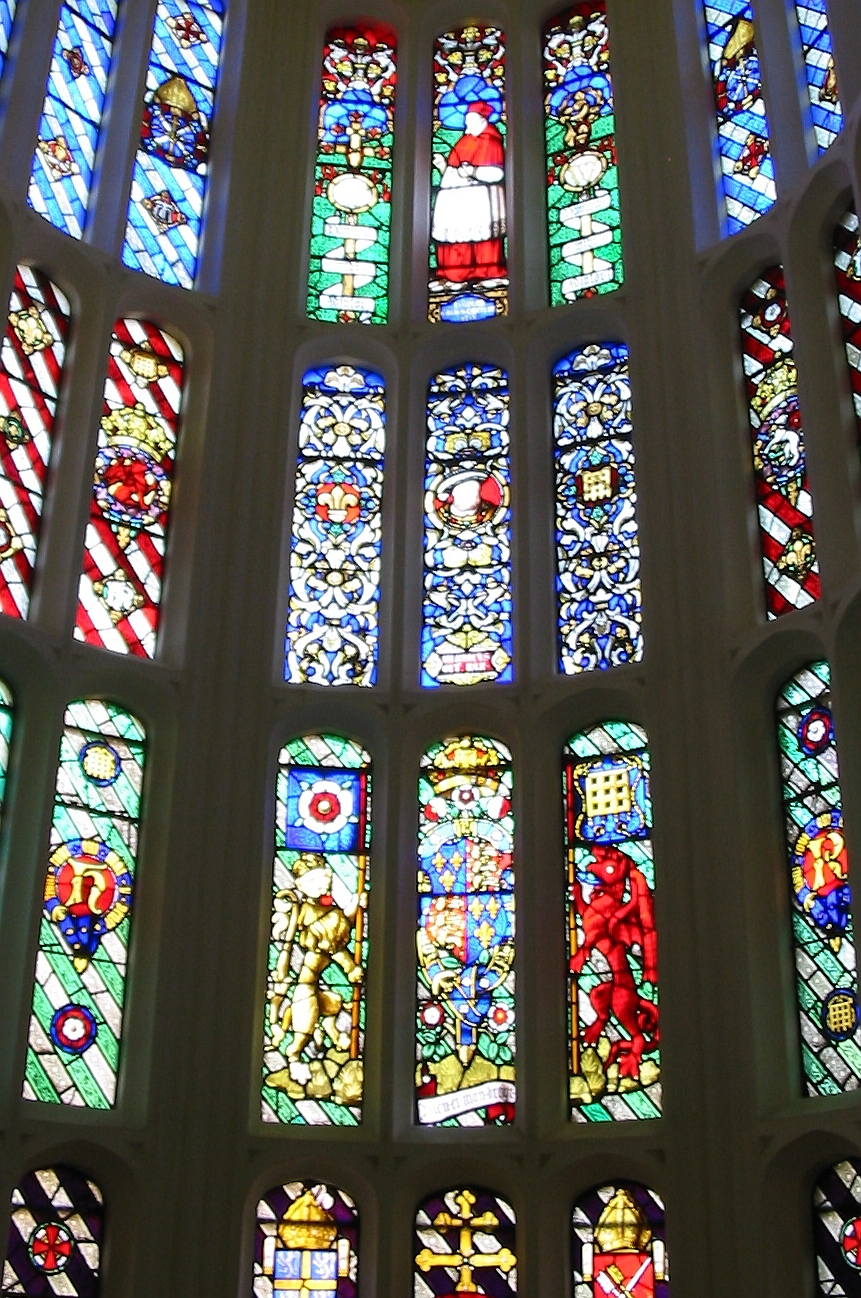

The timber and plaster ceiling of the chapel is considered the "most important and magnificent in Britain", but is all that remains of the Tudor decoration, after redecoration supervised by Sir Christopher Wren. The altar is framed by a massive but plain oak

The timber and plaster ceiling of the chapel is considered the "most important and magnificent in Britain", but is all that remains of the Tudor decoration, after redecoration supervised by Sir Christopher Wren. The altar is framed by a massive but plain oak

On the south side of the palace is the Privy Garden bounded by semi-circular wrought iron gates by

On the south side of the palace is the Privy Garden bounded by semi-circular wrought iron gates by  A well-known curiosity of the palace's grounds is Hampton Court Maze; planted in the 1690s by George London and Henry Wise for William III. It was originally planted with

A well-known curiosity of the palace's grounds is Hampton Court Maze; planted in the 1690s by George London and Henry Wise for William III. It was originally planted with

File:Garden in Hampton Court.jpg,

File:Hampton court garden - Yew trees (2016).jpg,

File:Rose Garden in Hampton Court.jpg,

Inspired by Wren's work at Hampton Court, the American

Inspired by Wren's work at Hampton Court, the American

Historic photos of Hampton Court Palace''Hampton Court''

by Walter Jerrold

Hampton Court Palace entry from The DiCamillo Companion to British & Irish Country HousesGrace & Favour: A handbook of who lived where at Hampton Court 1750–1950 (pdf)

– there are full floor plans of the palace on pages 10–13

Aerial photo and map of the Palace - Google MapsAerial view of the maze - Google MapsThe Hampton Court Garden FestivalThe Royal Tennis Court at Hampton Court PalaceThe Choir of The Chapel Royal at Hampton Court PalaceOnline 3D Virtual Hampton Maze browser simulation

{{Authority control 1514 establishments in England 1980s fires in the United Kingdom 1986 disasters in the United Kingdom Building and structure fires in London Buildings and structures on the River Thames Burned buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Christopher Wren buildings in London Country houses in London Edward Blore buildings Episcopal palaces of archbishops of York Gardens in London George I of Great Britain George II of Great Britain Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Grade I listed gates Grade I listed museum buildings Grade I listed parks and gardens in London Henry VIII Historic Royal Palaces Historic house museums in London History of Middlesex History of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Houses completed in 1514 Houses in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Mazes in the United Kingdom Middlesex Museums established in 1838 Museums in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Museums on the River Thames Nicholas Hawksmoor buildings Prince William, Duke of Cumberland Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Royal buildings in London Royal residences in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Royal residences in the United Kingdom Tudor royal palaces in England Venues of the 2012 Summer Olympics Edward VI Jane Seymour Catherine Howard

Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

The London Borough of Richmond upon Thames () in south-west Greater London, London, England, forms part of Outer London and is the only London boroughs, London borough on both sides of the River Thames. It was created in 1965 when three smaller ...

, southwest and upstream of central London

Central London is the innermost part of London, in England, spanning the City of London and several boroughs. Over time, a number of definitions have been used to define the scope of Central London for statistics, urban planning and local gove ...

on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

. Opened to the public, the palace is managed by Historic Royal Palaces, a charity set up to preserve several unoccupied royal properties.

The building of the palace began in 1514 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

, Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

and the chief minister of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

. In 1529, as Wolsey fell from favour, the cardinal gave the palace to the king to try to save his own life, which he knew was now in grave danger due to Henry VIII's deepening frustration and anger. The palace went on to become one of Henry's most favoured residences; soon after acquiring the property, he arranged for it to be enlarged so it could accommodate his sizeable retinue of courtiers

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other Royal family, royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as ...

.

In the early 1690s, William III's massive rebuilding and expansion work, which was intended to rival the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, destroyed much of the Tudor palace.Dynes, p. 90. His work ceased in 1694, leaving the palace in two distinct contrasting architectural styles, domestic Tudor and Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

. While the palace's styles are an accident of fate, a unity exists due to the use of pink bricks and a symmetrical, if vague, balancing of successive low wings.Dynes, p. 86. George II was the last monarch to reside in the palace.

The palace is open to the public and a major tourist attraction, reached by train from Waterloo station in central London and served by Hampton Court railway station in East Molesey

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

. Buses 111, 216, 411, 461 and R68 stop outside the gates. The structure and grounds are cared for by an independent charity, Historic Royal Palaces, which receives no funding from the Government or the Crown. The palace displays many works of art from the Royal Collection

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic List of British royal residences, royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King ...

.

Apart from the palace itself and its gardens, other points of interest for visitors include the celebrated maze, the historic royal tennis court (see below), and a huge grape vine

''Vitis'' (grapevine) is a genus of 81 accepted species of vining plants in the flowering plant family Vitaceae. The genus consists of species predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. It is economically important as the source of grapes, bot ...

, the world's largest . The palace's Home Park is the site of the annual Hampton Court Palace Festival and Hampton Court Garden Festival.

History

Medieval

What would become Hampton Court Palace was originally a property of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. It was leased first to John Wode in the mid-15th century, and then to the statesman Sir Giles Daubeney in 1494. Daubeney expanded the previous structures, and built the Great Kitchens that still survive today (although much altered). After Daubeney's death in 1508, his 14 year-old heir, Henry Daubeney, had to wait until 1514 to inherit his father's possessions. A month later, he relinquished his lease, and the Order of St John of Jerusalem re-leased Hampton Court toThomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

.

Tudor times

Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

, Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

, chief minister to and a favourite of Henry VIII, took over the site of Hampton Court Palace in 1514.Summerson, p. 12. Over the following seven years, Wolsey spent lavishly (200,000 crowns) to build the finest palace in England at Hampton Court. Today, little of Wolsey's building work remains unchanged. The first courtyard, the Base Court, (''B on plan''), was his creation, as was the second, inner gatehouse (''C'') which leads to the Clock Court (''D'') (Wolsey's seal remains visible over the entrance arch of the clock towerSpelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace: architectural description, ''A History of the County of Middlesex'', Volume 2General; Ashford, East Bedfont with Hatton, Feltham, Hampton with Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton (1911), pp. 371–379. Retrieved 21 March 2009.) which contained his private rooms (''O on plan''). The Base Court contained forty-four lodgings reserved for guests, while the second court (today, Clock Court) contained the very best rooms the

state apartments

A state room or stateroom in a large European mansion is usually one of a suite of very grand rooms which were designed for use when entertaining royalty. The term was most widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries. They were the most lavishly ...

reserved for the king and his family.Thurley, p. 6. Henry VIII stayed in the state apartments as Wolsey's guest immediately after their completion in 1525.

In building his palace, Wolsey was attempting to create a Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

cardinal's palace of a rectilinear symmetrical plan with grand apartments on a raised piano nobile

( Italian for "noble floor" or "noble level", also sometimes referred to by the corresponding French term, ) is the architectural term for the principal floor of a '' palazzo''. This floor contains the main reception and bedrooms of the house ...

, all rendered with classical detailing. The historian Jonathan Foyle has suggested that it is likely that Wolsey had been inspired by Paolo Cortese's ''De Cardinalatu'', a manual for cardinals that included advice on palatial architecture, published in 1510. The architectural historian Sir John Summerson

Sir John Newenham Summerson (25 November 1904 – 10 November 1992) was one of the leading British architectural historians of the 20th century.

Early life

John Summerson was born at Barnstead, Coniscliffe Road, Darlington. His grandfather wo ...

asserts that the palace shows "the essence of Wolseythe plain English churchman who nevertheless made his sovereign the arbiter of Europe and who built and furnished Hampton Court to show foreign embassies that Henry VIII's chief minister knew how to live as graciously as any cardinal in Rome."Summerson, p. 14. Whatever the concepts were, the architecture is an excellent and rare example of a thirty-year era when English architecture was in a harmonious transition from domestic Tudor, strongly influenced by perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-ce ...

, to the Italian Renaissance classical style. Perpendicular Gothic owed nothing historically to the Renaissance style, yet harmonised well with it.Copplestone, p. 254. This blending of styles was realised by a small group of Italian craftsmen working at the English court in the second and third decades of the sixteenth century. They specialised in the adding of Renaissance ornament to otherwise straightforward Tudor buildings. It was one of these, Giovanni da Maiano, who was responsible for the set of eight relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

busts of Roman emperors which were set in the Tudor brickwork.

Henry VIII and his courtiers visited Wolsey at Hampton Court in

Henry VIII and his courtiers visited Wolsey at Hampton Court in masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

costume in January 1527, disguised as shepherds to play mumchance and dance. Wolsey was only to enjoy his palace for a few years. In 1529, knowing that his enemies and the King were engineering his downfall, he passed the palace to the King as a gift. Wolsey died in 1530.

Within six months of coming into ownership, the King began his own rebuilding and expansion. Henry VIII's court consisted of over one thousand people. While the King owned over sixty houses and palaces, few of these were large enough to hold the assembled court, and thus one of the first of the King's building works (in order to transform Hampton Court to a principal residence) was to build the vast kitchens. These were quadrupled in size in 1529, enabling the King to provide bouche of court

The bouche of court, or vulgarly budge of court, is generally free food and drink at a royal court

A royal court, often called simply a court when the royal context is clear, is an extended royal household in a monarchy, including all those wh ...

(free food and drink) for his entire court. The architecture of King Henry's new palace followed the design precedent set by Wolsey: perpendicular Gothic-inspired Tudor with restrained Renaissance ornament. This hybrid architecture was to remain almost unchanged for nearly a century, until Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was an English architect who was the first significant Architecture of England, architect in England in the early modern era and the first to employ Vitruvius, Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmet ...

introduced strong classical influences from Italy to the London palaces of the first Stuart kings.

Between 1532 and 1535 Henry added the Great Hall (the last medieval great hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages. It continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the great cha ...

built for the English monarchy) and the Royal Tennis Court. The Great Hall has a carved hammerbeam roof

A hammerbeam roof is a decorative, open timber roof truss typical of English Gothic architecture and has been called "the most spectacular endeavour of the English Medieval carpenter". They are traditionally timber framed, using short beams proj ...

. During Tudor times, this was the most important room of the palace: here, the King would dine in state seated at a table upon a raised dais

A dais or daïs ( or , American English also but sometimes considered nonstandard)dais

in the Random House Dictionary< ...

. The hall took five years to complete; so impatient was the King for completion that the masons were compelled to work throughout the night by candlelight.

The gatehouse to the second, inner court was adorned in 1540 with the Hampton Court astronomical clock, an early example of a pre- Copernican in the Random House Dictionary< ...

astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition ...

. Still functioning, the clock shows the time of day, the phases of the moon, the month, the quarter of the year, the date, the sun and star sign, and high water

High Water or Highwater may refer to:

* High water, the state of tide when the water rises to its highest level.

Film and television

* Highwater (film), ''Highwater'' (film), a 2008 documentary

* ''Step Up: High Water'', a web television series

* ...

at London Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

. This last item was of great importance to those visiting this Thames-side palace from London, as the preferred method of transport at the time was by barge, and at low water London Bridge created dangerous rapids. This gatehouse is also known today as Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

's gate, after Henry's second wife. Work was still under way on Anne Boleyn's apartments above the gate when Boleyn was beheaded.

During the Tudor period, the palace was the scene of many historic events. In 1537, the King's much desired male heir, the future

During the Tudor period, the palace was the scene of many historic events. In 1537, the King's much desired male heir, the future Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

, was born at the palace, and the child's mother, Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (; 24 October 1537) was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen following the execution of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn, who was ...

, died there two weeks later.Thurley, p. 9. Four years afterwards, whilst attending Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

in the palace's chapel, the King was informed of the adultery of his fifth wife, Catherine Howard

Catherine Howard ( – 13 February 1542) was Queen of England from July 1540 until November 1541 as the fifth wife of King Henry VIII. She was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard and Joyce Culpeper, a first cousin to Anne Boleyn (the second ...

. She was then confined to her room for a few days before being sent to Syon House and then on to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

. Legend claims she briefly escaped her guards and ran through the Haunted Gallery to beg Henry for her life but she was recaptured.Thurley, p. 23.

King Henry died in January 1547 and was succeeded by his son Edward VI, and then by both his daughters in turn. It was to Hampton Court that Queen Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

(Henry's elder daughter) retreated with King Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

to spend her honeymoon, after their wedding at Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

.Williams, p. 52. Mary chose Hampton Court as the place for the birth of her first child, which turned out to be the first of two phantom pregnancies

False pregnancy (or pseudocyesis, ) is the appearance of clinical or subclinical signs and symptoms associated with pregnancy although the individual is not physically carrying a fetus. The mistaken impression that one is pregnant includes sign ...

. Mary had initially wanted to give birth at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

as it was a more secure location, and she was still fearful of rebellion. But Hampton Court was considerably larger and could accommodate the entire court and more besides. Mary stayed at the palace awaiting the birth of the "child" for over five months, and only left because of the uninhabitable state of the palace due to the court being kept in the one location for so long. Her court departed for the much smaller Oatlands Palace. Mary was succeeded by her half-sister, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

, and it was Elizabeth who had the eastern (privy) kitchen built; today, this is the palace's public tea room.

Stuarts and early Hanoverians

On the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the Tudor period came to an end. The Queen was succeeded by her first cousin-twice-removed, James I of the

On the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the Tudor period came to an end. The Queen was succeeded by her first cousin-twice-removed, James I of the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a dynasty, royal house of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and later Kingdom of Great Britain, Great ...

, an event known as the Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

.

Two entertainments for the Stuart court were staged in the Great Hall in January 1604, '' The Masque of Indian and China Knights'' and '' The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses''. On 6 January, Scottish courtiers performed a sword dance

Weapon dances incorporating swords or similar weapons are recorded throughout world history. There are various traditions of Solo dance, solo and mock-battle (Pyrrhic dance, Pyrrhic) sword dances in Africa, Asia and Europe. Some traditions use ...

for Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

. Their dance was compared to a Spanish '' matachin''. Later in 1604, the palace was the site of King James' meeting with representatives of the English Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, known as the Hampton Court Conference

The Hampton Court Conference was a meeting in January 1604, convened at Hampton Court Palace, for discussion between King James I of England and representatives of the Church of England, including leading English Puritans. The conference resulted ...

; while an agreement with the Puritans was not reached, the meeting led to James's commissioning of the King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English Bible translations, Early Modern English translation of the Christianity, Christian Bible for the Church of England, wh ...

of the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

.Thurley, p. 10.

King James was succeeded in 1625 by his son, the ill-fated Charles I. Hampton Court was to become both his palace and his prison. It was also the setting for his honeymoon with his fifteen-year-old bride, Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria of France (French language, French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to K ...

in 1625. Following King Charles' execution in 1649, the palace became the property of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

presided over by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

. Unlike some other former royal properties, the palace escaped relatively unscathed. While the government auctioned much of the contents, the building was ignored.

After the Restoration, King Charles II and his successor James II visited Hampton Court but largely preferred to reside elsewhere. By current French court standards, Hampton Court now appeared old-fashioned. It was in 1689, shortly after Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

's court had moved permanently to Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, that the palace's antiquated state was addressed. England had joint monarchs, William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland with her husband, King William III and II, from 1689 until her death in 1694. Sh ...

. Within months of their accession, they embarked on a massive rebuilding project at Hampton Court. The intention was to demolish the Tudor palace a section at a time while replacing it with a huge modern palace in the Baroque style retaining only Henry VIII's Great Hall.Summerson, p. 16.

The country's most eminent architect, Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

, was called upon to draw the plans, while the master of works was to be William Talman. The plan was for a vast palace constructed around two courtyards at right angles to each other. Wren's design for a domed palace bore resemblances to the work of Jules Hardouin-Mansart

Jules Hardouin-Mansart (; 16 April 1646 – 11 May 1708) was a French Baroque architect and builder whose major work included the Place des Victoires (1684–1690); Place Vendôme (1690); the domed chapel of Les Invalides (1690), and the Gra ...

and Louis Le Vau, both architects employed by Louis XIV at Versailles. It has been suggested, though, that the plans were abandoned because the resemblance to Versailles was too subtle and not strong enough; at this time, it was impossible for any sovereign to visualise a palace that did not emulate Versailles' repetitive Baroque form. However, the resemblances are there: while the façades are not so long as those of Versailles, they have similar, seemingly unstoppable repetitive rhythms beneath a long flat skyline. The monotony is even repeated as the façade turns the corner from the east to the south fronts. However, Hampton Court, unlike Versailles, is given an extra dimension by the contrast between the pink brick and the pale Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone geological formation (formally named the Portland Stone Formation) dating to the Tithonian age of the Late Jurassic that is quarried on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England. The quarries are cut in beds of whi ...

quoins, frames and banding.Dynes, p. 95. Further diversion is added by the circular and decorated windows of the second-floor mezzanine. This theme is repeated in the inner Fountain Court, but the rhythm is faster and the windows, unpedimented on the outer façades, are given pointed pediments in the courtyard; this has led the courtyard to be described as "Startling, as of simultaneous exposure to a great many eyes with raised eyebrows."Summerson, p. 19.

During this work, half the Tudor palace was replaced and Henry VIII's staterooms and private apartments were both lost; the new wings around the Fountain Court contained new state apartments and private rooms, one set for the King and one for the Queen. Each suite of state rooms was accessed by a state staircase. The royal suites were of completely equal value in order to reflect William and Mary's unique status as joint sovereigns.Williams, p. 54. The King's Apartments face south over the Privy Garden, the Queen's east over the Fountain Garden. The suites are linked by a gallery running the length of the east façade, another reference to Versailles, where the King and Queen's apartments are linked by the

During this work, half the Tudor palace was replaced and Henry VIII's staterooms and private apartments were both lost; the new wings around the Fountain Court contained new state apartments and private rooms, one set for the King and one for the Queen. Each suite of state rooms was accessed by a state staircase. The royal suites were of completely equal value in order to reflect William and Mary's unique status as joint sovereigns.Williams, p. 54. The King's Apartments face south over the Privy Garden, the Queen's east over the Fountain Garden. The suites are linked by a gallery running the length of the east façade, another reference to Versailles, where the King and Queen's apartments are linked by the Hall of Mirrors

The Hall of Mirrors () is a grand Baroque architecture, Baroque style gallery and one of the most emblematic rooms in the royal Palace of Versailles near Paris, France. The grandiose ensemble of the hall and its adjoining salons was intended to ...

. However, at Hampton Court, the linking gallery is of more modest proportions and decoration. The King's staircase was decorated with fresco

Fresco ( or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting become ...

s by Antonio Verrio and delicate ironwork by Jean Tijou

Jean Tijou () was a French Huguenot ironworker. He is known solely through his work in England, where he worked on several of the key English Baroque buildings. Very little is known of his biography. He arrived in England in c. 1689 and enjoyed ...

. Other artists commissioned to decorate the rooms included Grinling Gibbons

Grinling Gibbons (4 April 1648 – 3 August 1721) was an Anglo-Dutch sculptor and wood carver known for his work in England, including Windsor Castle, the Royal Hospital Chelsea and Hampton Court Palace, St Paul's Cathedral and other London church ...

, Sir James Thornhill and Jacques Rousseau; furnishings were designed by Daniel Marot.

After the death of Queen Mary, King William lost interest in the renovations, and work ceased. However, it was in Hampton Court Park in 1702 that he fell from his horse, later dying from his injuries at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is a royal residence situated within Kensington Gardens in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. It has served as a residence for the British royal family since the 17th century and is currently the ...

. He was succeeded by his sister-in-law Queen Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

who continued the decoration and completion of the state apartments. On Queen Anne's death in 1714 the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a dynasty, royal house of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and later Kingdom of Great Britain, Great ...

's rule came to an end.

Queen Anne's successor was George I; he and his son George II were the last monarchs to reside at Hampton Court. Under George I six rooms were completed in 1717 to the design of John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restor ...

.Thurley, Simon (2003). ''Hampton Court: A Social and Architectural History''. p. 255. Under George II and his wife, Caroline of Ansbach

Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach (Wilhelmina Charlotte Caroline; 1 March 1683 – 20 November 1737) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland and List of Hanoverian royal consorts, Electress of Hanover from 11 J ...

, further refurbishment took place, with the architect William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, b ...

employed to design new furnishings and décor including the Queen's Staircase, (1733)Thurley, Simon (2003). ''Hampton Court: A Social and Architectural History''. p. 279. and the Cumberland Suite (1737) for the Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British royal family, named after the historic county of Cumberland.

History

The Earldom of Cumberland, created in 1525, became extinct in 1643. The dukedom w ...

. Today, the Queen's Private Apartments are open to the public.

Later use

Since the reign of King George II, no monarch has resided at Hampton Court. In fact,George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

, from the moment of his accession, never set foot in the palace: he associated the state apartments with a humiliating scene when his grandfather, George II, had once struck him following an innocent remark. He did however have the Great Vine planted there in 1763 and had the top two storeys of the Great Gatehouse removed in 1773.

From the 1760s, the palace was used to house grace and favour residents. Many of the palace rooms were adapted to be rent-free apartments, with vacant ones allocated by the Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Households of the United Kingdom, Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Monarchy of the United Ki ...

to applicants to reward past services rendered to the Crown. From 1862 to his death in 1867, the scientist and pioneer of electricity Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

lived here. From the 1960s the number of new residents declined, with the last admitted in the 1980s. However existing residents could continue to live there. In 2005 three remained, with none by 2017.

In 1796, the Great Hall was restored and in 1838, during the reign of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, the restoration was completed and the palace opened to the public. The heavy-handed restoration plan at this time reduced the Great Gatehouse (''A''), the palace's principal entrance, by two storeys and removed the lead cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, usually dome-like structure on top of a building often crowning a larger roof or dome. Cupolas often serve as a roof lantern to admit light and air or as a lookout.

The word derives, via Ital ...

s adorning its four towers. Once opened, the palace soon became a major tourist attraction and, by 1881, over ten million visits had been recorded. Visitors arrived both by boat from London and via Hampton Court railway station, opened in February 1849.

On 2 September 1952, the palace was given statutory protection by being

On 2 September 1952, the palace was given statutory protection by being Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

. Other buildings and structures within the grounds are separately Grade I listed, including the early 16th-century tilt yard tower (the only surviving example of the five original towers); Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

's Lion gate built for Anne and George I; and the Tudor and 17th-century perimeter walls.

In 1986, the palace was damaged by a major fire, which spread to the King's Apartments. The fire claimed the life of Lady Daphne Gale, widow of General Sir Richard Gale, who resided in a grace and favour apartment. She was in the habit of taking a lighted candle to her bedroom at night, which is thought to have started the fire. The Hampton Court fire led to a new programme of restoration work which was completed in 1990. The Royal School of Needlework moved to premises within the palace from Princes Gate in Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

1987, and the palace also houses the headquarters of Historic Royal Palaces, a charitable foundation

A foundation (also referred to as a charitable foundation) is a type of nonprofit organization or charitable trust that usually provides funding and support to other charitable organizations through grants, while also potentially participating d ...

.

21st century

The location was used for a performance of '' The Six Wives of Henry VIII'' by rock keyboardistRick Wakeman

Richard Christopher Wakeman (born 18 May 1949) is an English keyboardist and composer best known as a member of the progressive rock band Yes across five tenures between 1971 and 2004, and for his prolific solo career. AllMusic describes Wakema ...

in 2009.

The palace was the venue for the Road Cycling Time Trial of the 2012 Summer Olympics

The 2012 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the XXX Olympiad and also known as London 2012, were an international multi-sport event held from 27 July to 12 August 2012 in London, England, United Kingdom. The first event, the ...

and temporary structures for the event, including a set of thrones for time trialists in the medal positions, were installed in the grounds.

In 2015, Hampton Court celebrated the 500th anniversary of the groundbreaking of construction of the palace. The celebrations included daily dramatised historical scenes. The palace's construction began on 12 February 1515.

On 9 February the following year, Vincent Nichols, the Catholic archbishop of Westminster, celebrated vespers

Vespers /ˈvɛspərz/ () is a Christian liturgy, liturgy of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Catholic (both Latin liturgical rites, Latin and Eastern Catholic liturgy, Eastern Catholic liturgical rites), Eastern Orthodox, Oriental O ...

in the Chapel Royal. This was the first Catholic service held at the palace for 450 years, and the first since the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Ref ...

established Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

as the national denomination.

Contents

The palace houses many works of art and furnishings from the

The palace houses many works of art and furnishings from the Royal Collection

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic List of British royal residences, royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King ...

, mainly dating from the two principal periods of the palace's construction, the early Tudor (Renaissance) and the late Stuart to the early Georgian period. In September 2015, the Royal Collection recorded 542 works (only those with images) as being located at Hampton Court, mostly paintings and furniture, but also ceramics and sculpture. The full current list can be obtained from their website. The single most important work is Andrea Mantegna

Andrea Mantegna (, ; ; September 13, 1506) was an Italian Renaissance painter, a student of Ancient Rome, Roman archeology, and son-in-law of Jacopo Bellini.

Like other artists of the time, Mantegna experimented with Perspective (graphical), pe ...

's '' Triumphs of Caesar'' housed in the Lower Orangery. The palace once housed the Raphael Cartoons

The Raphael Cartoons are seven large cartoon paintings on paper for tapestries, surviving from a set of ten cartoons, designed by the High Renaissance painter Raphael in 1515–1516. Commissioned by Pope Leo X for the Sistine Chapel in the ...

, now kept at the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

. Their former home, the Cartoon Gallery on the south side of the Fountain Court, was designed by Christopher Wren; copies painted in the 1690s by a minor artist, Henry Cooke, are now displayed in their place. Also on display are important collections of ceramics, including numerous pieces of blue and white porcelain collected by Queen Mary II, both Chinese imports and Delftware

Delftware or Delft pottery, also known as Delft Blue () or as delf,

is a general term now used for Dutch tin-glazed earthenware, a form of faience. Most of it is blue and white pottery, and the city of Delft in the Netherlands was the major cen ...

.

Much of the original furniture dates from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, including tables by Jean Pelletier, "India back" walnut chairs by Thomas Roberts and clocks and a barometer by Thomas Tompion. Several state beds are still in their original positions, as is the Throne Canopy in the King's Privy Chamber. This room contains a crystal chandelier of , possibly the first such in the country.

The King's Guard Chamber contains a large quantity of arms: muskets, pistols, swords, daggers, powder horns and pieces of armour arranged on the walls in decorative patterns. Bills exist for payment to a John Harris, dated 1699, for an arrangement believed to be that still seen today.

In addition, Hampton Court holds the majority of the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, with a smaller amount being held at

Much of the original furniture dates from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, including tables by Jean Pelletier, "India back" walnut chairs by Thomas Roberts and clocks and a barometer by Thomas Tompion. Several state beds are still in their original positions, as is the Throne Canopy in the King's Privy Chamber. This room contains a crystal chandelier of , possibly the first such in the country.

The King's Guard Chamber contains a large quantity of arms: muskets, pistols, swords, daggers, powder horns and pieces of armour arranged on the walls in decorative patterns. Bills exist for payment to a John Harris, dated 1699, for an arrangement believed to be that still seen today.

In addition, Hampton Court holds the majority of the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, with a smaller amount being held at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is a royal residence situated within Kensington Gardens in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. It has served as a residence for the British royal family since the 17th century and is currently the ...

, where it is displayed. The collection of over 10,000 items includes clothing, sketches, letters, prints, photographs, diaries and scrapbooks. The dress collection has designated status from Arts Council England

Arts Council England is an arm's length non-departmental public body of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Department for Culture, Media and Sport. It is also a registered charity. It was formed in 1994 when the Arts Council o ...

.

The Chapel

The timber and plaster ceiling of the chapel is considered the "most important and magnificent in Britain", but is all that remains of the Tudor decoration, after redecoration supervised by Sir Christopher Wren. The altar is framed by a massive but plain oak

The timber and plaster ceiling of the chapel is considered the "most important and magnificent in Britain", but is all that remains of the Tudor decoration, after redecoration supervised by Sir Christopher Wren. The altar is framed by a massive but plain oak reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a Church (building), church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular a ...

with garlands carved by Grinling Gibbons

Grinling Gibbons (4 April 1648 – 3 August 1721) was an Anglo-Dutch sculptor and wood carver known for his work in England, including Windsor Castle, the Royal Hospital Chelsea and Hampton Court Palace, St Paul's Cathedral and other London church ...

during the reign of Queen Anne. Opposite the altar, at first-floor level, is the royal pew where the royal family would attend services apart from the general congregation seated below.

The clergy, musicians and other ecclesiastical officers employed by the monarch at Hampton Court, as in other English royal premises, are known collectively as the Chapel Royal

A chapel royal is an establishment in the British and Canadian royal households serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the royal family.

Historically, the chapel royal was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarc ...

; properly used the term does not refer to a building.

Grounds

The grounds as they appear today were laid out in grand style in the late 17th century. There are no authentic remains of Henry VIII's gardens, merely a smallknot garden

A knot garden is a garden style that was popularized in 16th century England and is now considered an element of the formal English garden. A knot garden consists of a variety of aromatic and culinary herbs, or low hedges such as box, planted in ...

, planted in 1924, which hints at the gardens' 16th-century appearance.Thurley, p. 44. Today, the dominating feature of the grounds is the great landscaping scheme constructed for Sir Christopher Wren's intended new palace. From a water-bounded semicircular parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, plats, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the ...

, the length of the east front, three avenues radiate in a crow's foot pattern. The central avenue, containing not a walk or a drive, but the great canal known as the Long Water, was excavated during the reign of Charles II, in 1662. The design, radical at the time, is another immediately recognizable influence from Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

and was indeed laid out by pupils of André Le Nôtre

André Le Nôtre (; 12 March 1613 – 15 September 1700), originally rendered as André Le Nostre, was a French landscape architect and the principal gardener of King Louis XIV of France. He was the landscape architect who designed Gardens ...

, Louis XIV's landscape gardener.

On the south side of the palace is the Privy Garden bounded by semi-circular wrought iron gates by

On the south side of the palace is the Privy Garden bounded by semi-circular wrought iron gates by Jean Tijou

Jean Tijou () was a French Huguenot ironworker. He is known solely through his work in England, where he worked on several of the key English Baroque buildings. Very little is known of his biography. He arrived in England in c. 1689 and enjoyed ...

. This garden, originally William III's private garden, was replanted in 1992 in period style with manicured hollies and yews along a geometric system of paths.

On a raised site overlooking the Thames is a small pavilion, the Banqueting House. This was built , for informal meals and entertainments in the gardens rather than for the larger state dinners which would have taken place inside the palace itself. A nearby conservatory houses the "Great Vine", planted in 1769; by 1968 it had a trunk thick and has a length of . It still produces an annual crop of grapes.Thurley, p. 46.

The palace included apartments for the use of favoured royal friends. One such apartment is described as being in "The Pavilion and situated on the Home Park" of Hampton Court Palace. This privilege was first extended about 1817 by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III and Queen Charlotte. His only child, Queen Victoria, Victoria, became Queen of the United Ki ...

, to his friend, Lieutenant General James Moore, and his new bride, Cecilia Watson. George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

continued this arrangement following the death of Prince Edward on 23 January 1820. Queen Victoria continued the arrangement for the widow of General Moore, following his death on 24 April 1838. This particular apartment was used for 21 years or more and spanned three different sponsors.

A well-known curiosity of the palace's grounds is Hampton Court Maze; planted in the 1690s by George London and Henry Wise for William III. It was originally planted with

A well-known curiosity of the palace's grounds is Hampton Court Maze; planted in the 1690s by George London and Henry Wise for William III. It was originally planted with hornbeam

Hornbeams are hardwood trees in the plant genus ''Carpinus'' in the family Betulaceae. Its species occur across much of the temperateness, temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

Common names

The common English name ''hornbeam'' derives ...

; it has been repaired latterly using many different types of hedge. There is a 3D simulation of the maze, see the external links section.

Inspired by narrow views of a Tudor garden that can be seen through doorways in a painting, ''The Family of Henry VIII'', hanging in the palace's Haunted Gallery, a new garden in the style of Henry VIII's 16th-century Privy Gardens, has been designed to celebrate the anniversary of that King's accession to the throne. Sited on the former Chapel Court Garden, it has been planted with flowers and herbs from the 16th century and is completed by gilded heraldic beasts and bold green and white painted fences. The garden's architect was Todd Longstaffe-Gowan.

The formal gardens and park are Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

King's Beasts

There are ten statues of heraldic animals, called the King's Beasts, that stand on the bridge over the moat leading to the great gatehouse. Unlike the Queen's Beasts inKew Gardens

Kew Gardens is a botanical garden, botanic garden in southwest London that houses the "largest and most diverse botany, botanical and mycology, mycological collections in the world". Founded in 1759, from the exotic garden at Kew Park, its li ...

, these statues represent the ancestry of King Henry VIII and his third wife Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (; 24 October 1537) was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen following the execution of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn, who was ...

. The animals are: the lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'', native to Sub-Saharan Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body (biology), body; a short, rounded head; round ears; and a dark, hairy tuft at the ...

of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, the Seymour lion, the royal dragon

A dragon is a Magic (supernatural), magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but European dragon, dragons in Western cultures since the Hi ...

, the black bull of Clarence, the yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

of Beaufort, the white lion of Mortimer, the White Greyhound of Richmond, the Tudor dragon, the Seymour panther, and the Seymour unicorn

The unicorn is a legendary creature that has been described since Classical antiquity, antiquity as a beast with a single large, pointed, spiraling horn (anatomy), horn projecting from its forehead.

In European literature and art, the unico ...

. The set of Queen's Beasts at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

The Coronation of the British monarch, coronation of Elizabeth II as queen of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey in London. Elizabeth acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon th ...

replaced the three Seymour items and one of the dragons by the gryphon of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, the horse of Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

, the falcon of the Plantagenets, and the unicorn of Scotland.

In 2009 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the accession to the throne of King Henry VIII, a new "Tudor Garden" was created in Chapel Court, Hampton Court, designed by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan. To decorate the garden eight small wooden King's Beasts were carved and painted in bright colours, each sitting atop a 6-foot-high painted wooden column. The heraldic beasts, carved by Ben Harms and Ray Gonzalez of G&H Studios, include the golden lion of England, the white greyhound of Richmond, the red dragon of Wales, and the white hart of Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Joan, Countess of Kent. R ...

, all carved from English oak. The historically correct colours were researched by Patrick Baty, paint/colour consultant at Hampton Court. The beasts are of a different design to those on the bridge, based on period drawings in the College of Arms

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal corporation consisting of professional Officer of Arms, officers of arms, with jurisdiction over England, Wales, Northern Ireland and some Commonwealth realms. The heralds are appointed by the ...

.

Transport links

The palace is served by Hampton Court railway station which is immediately to the south of Hampton Court Bridge inEast Molesey

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

, and by London bus routes 111, 216, 411 and R68 from Kingston and Richmond.

Cultural appearances and influence

Florham, United States

Inspired by Wren's work at Hampton Court, the American

Inspired by Wren's work at Hampton Court, the American Vanderbilt family

The Vanderbilt family is an American family who gained prominence during the Gilded Age. Their success began with the shipping and railroad empires of Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the family expanded into various other areas of industry and philanth ...

modelled their estate known as Florham, in Madison, New Jersey

Madison is a Borough (New Jersey), borough in Morris County, New Jersey, Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 16,937, an increase of 1,092 (+6.9%) from the 2010 United ...

, US, after it. Florham was commissioned by Florence Adele Vanderbilt Twombly and Hamilton McKown Twombly from McKim, Mead & White

McKim, Mead & White was an American architectural firm based in New York City. The firm came to define architectural practice, urbanism, and the ideals of the American Renaissance in ''fin de siècle'' New York.

The firm's founding partners, Cha ...

. It was built in 1893.

Film location

The palace has been used as a location for filming film and television shows, including ''The Private Life of Henry VIII

''The Private Life of Henry VIII'' is a 1933 British biographical drama film directed and co-produced by Alexander Korda and starring Charles Laughton, Robert Donat, Merle Oberon and Elsa Lanchester. It was written by Lajos Bíró and Arthur ...

'', ''Three Men In A Boat

''Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog)'',The Penguin edition punctuates the title differently: ''Three Men in a Boat: To Say Nothing of the Dog!'' published in 1889, is a humorous novel by English writer Jerome K. Jerome describing ...

'', '' A Man For All Seasons'', '' Vanity Fair'', ''Little Dorrit

''Little Dorrit'' is a novel by English author Charles Dickens, originally published in Serial (literature), serial form between 1855 and 1857. The story features Amy Dorrit, youngest child of her family, born and raised in the Marshalsea pris ...

'', ''John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

'' (2008), ''The Young Victoria

''The Young Victoria'' is a 2009 British period drama, period drama film directed by Jean-Marc Vallée and written by Julian Fellowes, based on the early life and reign of Queen Victoria, and her marriage to Albert, Prince Consort, Prince Albert ...

'', '' Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides'', '' Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows'', '' The Theory of Everything'', ''Cinderella

"Cinderella", or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a Folklore, folk tale with thousands of variants that are told throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988. The protagonist is a you ...

,'' '' Mamma Mia: Here We Go Again!'', '' The Favourite'', ''Belgravia

Belgravia () is a district in Central London, covering parts of the areas of the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Belgravia was known as the 'Five Fields' during the Tudor Period, and became a dangerous pla ...

'', '' The Great,'' and ''Bridgerton

''Bridgerton'' is an American alternative history regency romance television series created by Chris Van Dusen for Netflix. Based on the book series Bridgerton (novel series), of the same name by Julia Quinn, it is Shondaland's first scripted ...

''. Some scenes of the spin-off series, '' Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story'', were also filmed at the palace.

Poetry

Lydia Sigourney

Lydia Huntley Sigourney (September 1, 1791 – June 10, 1865), Lydia Howard Huntley, was an American poet, author, and publisher during the early and mid 19th century. She was commonly known as the "Sweet Singer of Hartford, Connecticut, Hartfor ...

's poem ''Hampton Court'' records a visit to the palace with the bridal party following a wedding in March, 1841. It was published in her ''Pleasant Memories of Pleasant Lands'' in 1842.

See also

* Coughton Court inWarwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Staffordshire and Leicestershire to the north, Northamptonshire to the east, Ox ...

* Het Loo Palace

Paleis Het Loo ( , meaning "The wikt:lea#English, Lea") is a palace in Apeldoorn, Netherlands, built by the House of Orange-Nassau.

History

The symmetry, symmetrical Dutch Baroque architecture, Dutch Baroque building was designed by Jacob Roman ...

in the Netherlands

* List of works of art at Hampton Court Palace

* Treaty of Hampton Court (1562), also known as the Treaty of Richmond, signed on 22 September 1562 between Queen Elizabeth and Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

leader Louis I, Prince of Condé

* Hampton Court ghost

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * Williams, Neville (1971). ''Royal Homes''. Lutterworth Press. .External links

*Historic photos of Hampton Court Palace

by Walter Jerrold

Hampton Court Palace entry from The DiCamillo Companion to British & Irish Country Houses

– there are full floor plans of the palace on pages 10–13

Aerial photo and map of the Palace - Google Maps

{{Authority control 1514 establishments in England 1980s fires in the United Kingdom 1986 disasters in the United Kingdom Building and structure fires in London Buildings and structures on the River Thames Burned buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Christopher Wren buildings in London Country houses in London Edward Blore buildings Episcopal palaces of archbishops of York Gardens in London George I of Great Britain George II of Great Britain Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Grade I listed gates Grade I listed museum buildings Grade I listed parks and gardens in London Henry VIII Historic Royal Palaces Historic house museums in London History of Middlesex History of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Houses completed in 1514 Houses in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Mazes in the United Kingdom Middlesex Museums established in 1838 Museums in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Museums on the River Thames Nicholas Hawksmoor buildings Prince William, Duke of Cumberland Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Royal buildings in London Royal residences in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Royal residences in the United Kingdom Tudor royal palaces in England Venues of the 2012 Summer Olympics Edward VI Jane Seymour Catherine Howard