HMS Centurion (1911) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Centurion'' was the second of four

A fire-control director was installed on the roof of the spotting top before August 1914; her original pole

A fire-control director was installed on the roof of the spotting top before August 1914; her original pole

Jellicoe's ships, including ''Centurion'', conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of

Jellicoe's ships, including ''Centurion'', conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of

''Centurion'' was being refitted when the Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German

''Centurion'' was being refitted when the Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German  In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany. The ship was present at

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany. The ship was present at

In 1939–1940, the ship continued in her prewar role, although she was briefly considered for rearming in May 1940 as an anti-aircraft cruiser in support of the Norway campaign. She then served as a repair ship at Devonport before being converted into a blockship in April 1941. On 14 April,

In 1939–1940, the ship continued in her prewar role, although she was briefly considered for rearming in May 1940 as an anti-aircraft cruiser in support of the Norway campaign. She then served as a repair ship at Devonport before being converted into a blockship in April 1941. On 14 April,  In 1942, ''Centurion'' was transferred to the

In 1942, ''Centurion'' was transferred to the

Maritimequest HMS Centurion Photo Gallery

Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project – HMS Centurion Crew List

{{DEFAULTSORT:Centurion (1911) King George V-class battleships (1911) Ships built in Plymouth, Devon 1911 ships World War I battleships of the United Kingdom World War II battleships of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean Shipwrecks of France Scuttled vessels of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in June 1944 Ships sunk as breakwaters

dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

s built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in the early 1910s. She spent the bulk of her career assigned to the Home

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or more human occupants, and sometimes various companion animals. Homes provide sheltered spaces, for instance rooms, where domestic activity can be p ...

and Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

s. Aside from participating in the failed attempt to intercept the German ships that had bombarded Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in late 1914, and the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

in May 1916, her service during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

.

By the end of 1919, ''Centurion'' had been transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

. Although she spent much of her time in reserve, she had a peripheral role in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions that began in 1918. The initial impetus behind the interventions was to secure munitions and supply depots from falling into the German ...

. After her return home in 1924, the ship became the flagship of the Reserve Fleet. In 1926 ''Centurion'' was converted into a target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammunit ...

and participated in trials evaluating the effectiveness of aerial bombing

An airstrike, air strike, or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighter aircraft, attack aircraft, bombers, attack helicopters, and drones. The official d ...

in addition to her normal duties. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the ship was rearmed with light weapons and was converted into a blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used as a waterway. It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of at Portland ...

in 1941. When that operation was cancelled, she was then modified into a decoy

A decoy (derived from the Dutch ''de'' ''kooi'', literally "the cage" or possibly ''eenden kooi'', " duck cage") is usually a person, device, or event which resembles what an individual or a group might be looking for, but it is only meant to ...

with dummy gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s in an attempt to fool the Axis powers. ''Centurion'' was sent to the Mediterranean in 1942 to escort a convoy to Malta, although the Italians quickly saw through the deception. The ship was deliberately sunk during the Invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 ( D-Day) with the ...

in 1944 to form a breakwater

Breakwater may refer to:

* Breakwater (structure), a structure for protecting a beach or harbour

Places

* Breakwater, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria, Australia

* Breakwater Island, Antarctica

* Breakwater Islands, Nunavut, Canada

* ...

.

Design and description

The ''King George V''-class ships were designed as enlarged and improved versions of the preceding . They had anoverall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam of and a draught of . They displaced at normal load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. ''Centurion''s crew numbered 862 officers and ratings upon completion.Burt 1986, p. 176

Ships of the ''King George V'' class were powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s, each driving two shafts, using steam provided by 18 Yarrow boiler

Yarrow boilers are an important class of high-pressure water-tube boilers. They were developed by

Yarrow Shipbuilders, Yarrow & Co. (London), Shipbuilders and Engineers and were widely used on ships, particularly warships.

The Yarrow boiler desi ...

s. The turbines were rated at and were intended to give the battleships a speed of .Parkes, p. 538 During her sea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s on 19–20 February 1913, ''Centurion'' reached a maximum speed of from . She carried enough coal and fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

to give her a range of at a cruising speed of .

Armament and armour

Like the ''Orion'' class, the ''King George V''s were equipped with 10 breech-loading (BL) Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets, all on the centreline. The turrets were designated 'A', 'B', 'Q', 'X' and 'Y', from front to rear. Theirsecondary armament

Secondary armaments are smaller, faster-firing weapons that are typically effective at a shorter range than the main battery, main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored personnel c ...

consisted of 16 BL Mark VII guns. Eight of these were mounted in the forward superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, four in the aft superstructure, and four in casemates in the side of the hull abreast of the forward main gun turrets, all in single mounts. Four saluting guns were also carried. The ships were equipped with three 21-inch (533 mm) submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one on each broadside and another in the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

, for which 14 torpedoes were provided.

The ''King George V''-class ships were protected by a waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

armoured belt that extended between the end barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s. Their decks ranged in thickness between and 4 inches with the thickest portions protecting the steering gear in the stern. The main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

turret faces were thick, and the turrets were supported by barbettes.

Modifications

A fire-control director was installed on the roof of the spotting top before August 1914; her original pole

A fire-control director was installed on the roof of the spotting top before August 1914; her original pole foremast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the median line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, giving necessary height to a navigation light ...

was reinforced by short tripod legs to stiffen it and allow it to bear the weight of the director. By October 1914, a pair of anti-aircraft (AA) guns had been added on the quarterdeck

The quarterdeck is a raised deck behind the main mast of a sailing ship. Traditionally it was where the captain commanded his vessel and where the ship's colours were kept. This led to its use as the main ceremonial and reception area on bo ...

. Approximately of additional deck armour was added after the Battle of Jutland. By April 1917, the four-inch guns had been removed from the hull casemates as they were frequently unusable in heavy seas. The casemates were plated over and some of the compartments were used for accommodations. In addition, one of the three-inch AA guns was replaced by a four-inch AA gun. Her stern torpedo tube was removed in either 1917 or 1918 and flying-off platforms were fitted on the roofs of 'B' and 'X' turrets during 1918.

When ''Centurion'' was initially converted for use as a radio-controlled target ship for use by ships with guns up to in diameter in 1926, the conversion was initially fairly minimal. All of her small fittings were removed, her boilers were converted to use diesel fuel instead of coal and numerous radio antennas were added for use by her controlling ship, the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

. The ship could steam at speeds of for three hours. Her gun turrets were removed shortly afterwards and some of the former coal bunkers were filled with rocks to compensate for weight of the turrets. This increased her draught to which reduced the chances of steeply diving shells fired at maximum range penetrating beneath the armour belt. The ship was maintained by a crew of 242 who sailed her to the firing range and then disembarked. The spotting top was removed by 22 September 1930 and her forward superstructure was cut down and her funnels

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

were shortened in 1933 in preparation for aircraft bombing trials.

''Centurion'' was armed with a variety of weapons in June 1940 as the threat of German invasion increased and was then modified to serve as a repair ship for the local defence ships based in Devonport. In April–May 1941, she was converted into a blockship,Burt 1986, p. 181 with her magazines

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

now serving as fuel tanks, but she was then modified with false gun turrets and masts to serve as a decoy for the battleship . Her armament now comprised two 2-pounder (40 mm) Mk II "pom-pom"s and eight Oerlikon light AA guns, all on single mounts. The ship's anti-aircraft armament was augmented in June 1942 with two additional "pom-pom"s and nine more Oerlikons.

Construction and career

''Centurion'', named after theRoman Army

The Roman army () served ancient Rome and the Roman people, enduring through the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC), the Roman Republic (509–27 BC), and the Roman Empire (27 BC–AD 1453), including the Western Roman Empire (collapsed Fall of the W ...

rank of centurion

In the Roman army during classical antiquity, a centurion (; , . ; , or ), was a commander, nominally of a century (), a military unit originally consisting of 100 legionaries. The size of the century changed over time; from the 1st century BC ...

, was the sixth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy. She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at HM Dockyard, Devonport on 16 January 1911 and launched on 18 November.Preston, p. 30 While conducting her sea trials on the night of 9/10 December, ''Centurion'' accidentally rammed and sank the Italian steamer with the loss of all hands. The battleship's bow was badly damaged and the ship was under repair until March 1913. She cost £1,950,671 at completion and was commissioned on 22 May, joining her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

s in the 2nd Battle Squadron (BS). The ship was present with the 2nd BS to receive the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is the supreme magistracy of the country, the po ...

, Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

, at Spithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

on 24 June. All four sisters represented the Royal Navy during the celebrations of the re-opening of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal, held in conjunction with Kiel Week

The Kiel Week () or Kiel Regatta is an annual sailing event in Kiel, the capital of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is considered to be one of the largest sailing events globally, and also the largest summer festivals in Northern Europe, ...

, in Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

, Germany, in June 1914.Burt 1986, p. 188

First World War

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, ''Centurion'' took part in a testmobilisation

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

and fleet review as part of the British response to the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the Great power, major powers of Europe in mid-1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I. It began on 28 June 1914 when the Serbs ...

. Arriving in Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

on 25 July, she was ordered to proceed with the rest of the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

four days later to safeguard the fleet from a possible surprise attack by the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

. In August 1914, following the outbreak of the First World War, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

, and placed under the command of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Sir John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland ...

. Repeated reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and he ordered that the Grand Fleet be dispersed to other bases until the defences be reinforced. On 16 October the 2nd BS was sent to Loch na Keal on the western coast of Scotland. The squadron departed for gunnery practice off the northern coast of Ireland on the morning of 27 October and her sister struck a mine, laid a few days earlier by the German auxiliary minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine, military aircraft or land vehicle deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for ins ...

. Thinking that the ship had been torpedoed by a submarine, the other dreadnoughts were ordered away from the area, while smaller ships rendered assistance. On the evening of 22 November 1914, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

; ''Centurion'' stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of vic ...

David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November.

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

The Royal Navy'sRoom 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans for a German attack on Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, sub ...

, Hartlepool

Hartlepool ( ) is a seaside resort, seaside and port town in County Durham, England. It is governed by a unitary authority borough Borough of Hartlepool, named after the town. The borough is part of the devolved Tees Valley area with an estimat ...

and Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

in mid-December using the four battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

s of ''Konteradmiral

(; abbreviated KAdm) is a senior naval flag officer rank in several German-speaking countries, equivalent to counter or rear admiral.

Austria-Hungary

In the Austro-Hungarian '' K.u.K. Kriegsmarine'' (1849 to 1918) there were the flag of ...

'' (Rear-Admiral) Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (born Franz Hipper; 13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy, (''Kaiserliche Marine'') who played an important role in the naval warfare of World War I. Franz von Hipper joined th ...

's I Scouting Group. The radio messages did not mention that the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

with fourteen dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appl ...

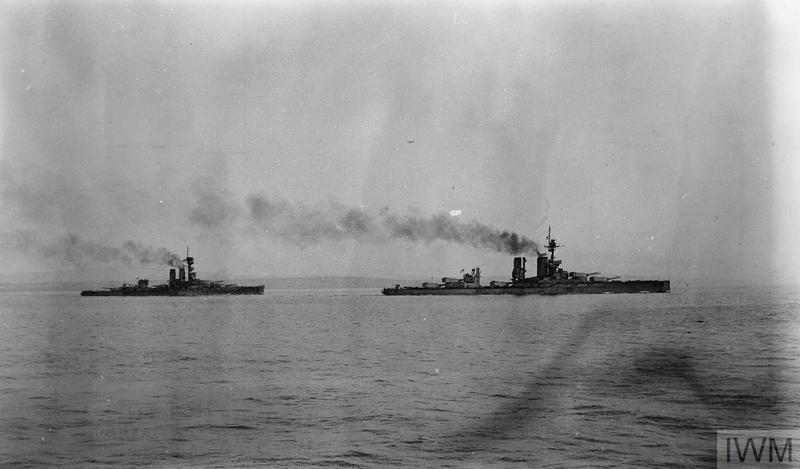

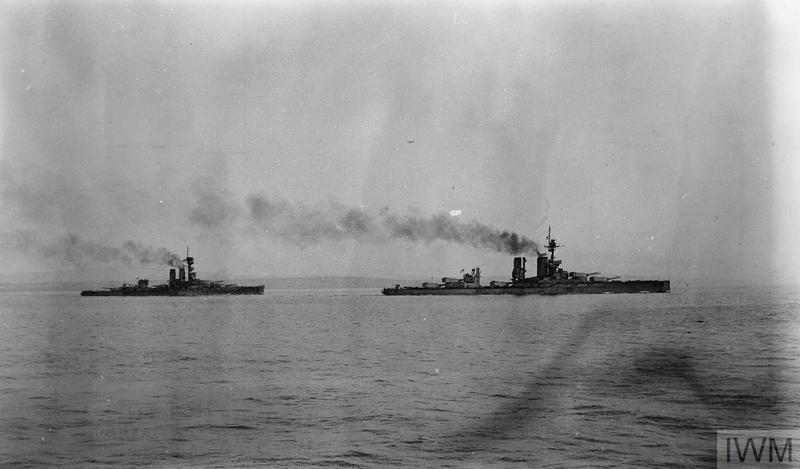

s would reinforce Hipper. The ships of both sides departed their bases on 15 December, with the British intending to ambush the German ships on their return voyage. They mustered the six dreadnoughts of the 2nd BS, including ''Centurion'' and her sisters and , and stood with the main body in support of Beatty's four battlecruisers.

The screening forces of each side blundered into each other during the early morning darkness of 16 December in heavy weather. The Germans got the better of the initial exchange of fire, severely damaging several British destroyers, but von Ingenohl, commander of the High Seas Fleet, ordered his ships to turn away, concerned about the possibility of a massed attack by British destroyers in the dawn's light. A series of miscommunications and mistakes by the British allowed Hipper's ships to avoid an engagement with Beatty's forces.

1915–1916

Jellicoe's ships, including ''Centurion'', conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of

Jellicoe's ships, including ''Centurion'', conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

and the Shetland Islands

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the Uni ...

. On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers, but ''Centurion'' and the rest of the fleet did not participate in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day. The ship was refitted at Cromarty

Cromarty (; , ) is a town, civil parishes in Scotland, civil parish and former royal burgh in Ross and Cromarty, in the Highland (council area), Highland area of Scotland. Situated at the tip of the Black Isle on the southern shore of the mout ...

, Scotland, from 25 January to 22 February. On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet conducted a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March. On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June, the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland and more training off Shetland beginning on 11 July. The 2nd BS conducted gunnery practice in the Moray Firth

The Moray Firth (; , or ) is a roughly triangular inlet (or firth) of the North Sea, north and east of Inverness, which is in the Highland council area of the north of Scotland.

It is the largest firth in Scotland, stretching from Duncans ...

on 2 August and then returned to Scapa Flow. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, conducted another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, ''Centurion'' participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November and repeated the exercise at the beginning of December.

The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, it ...

to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyers. On the night of 25 March, ''Centurion'' and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface wind moving at a speed between .

threatened the light craft, so the fleet was ordered to return to base. On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

. The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft, but only arrived in the area after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea. It is uncertain if ''Centurion'' participated in this as she received a brief refit at Invergordon

Invergordon (; or ) is a town and port in Easter Ross, in Ross and Cromarty, Highland (council area), Highland, Scotland. It lies in the parish of Rosskeen.

History

The town built up around the harbour which was established in 1828. The area ...

, Scotland, during the month.

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed theJade Bight

The Jade Bight (also known as ''Jade Bay''; , ) is a bight or bay on the North Sea coast of Germany. It was formerly known simply as (the) Jade or Jahde. Because of the very low input of freshwater, it is classified as a bay rather than an e ...

early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Hipper's five battlecruisers. Room 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.

On 31 May, ''Centurion'', under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Sir Michael Culme-Seymour, was the third ship from the head of the battle line

The line of battle or the battle line is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships (known as ships of the line) forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for date ...

after deployment. The ship was only lightly engaged at Jutland, firing four salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in many blows at once and prevent them from f ...

s (totalling 19 armour-piercing shells) at the battlecruiser at 19:16The times used in this section are in UT, which is one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works. before blocked ''Centurion''s view, failing to hit her target.

Subsequent activity

''Centurion'' was being refitted when the Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German

''Centurion'' was being refitted when the Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany. The ship was present at

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany. The ship was present at Rosyth

Rosyth () is a town and Garden City in Fife, Scotland, on the coast of the Firth of Forth.

Scotland's first Garden city movement, Garden City, Rosyth is part of the Greater Dunfermline Area and is located 3 miles south of Dunfermline city cen ...

, Scotland, when the High Seas Fleet surrendered there on 21 November.

Between the wars

By 18 December 1919, ''Centurion'' had been assigned to the 4th Battle Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet. In March 1920, the ship was temporarily placed in reserve, but was recommissioned on 8 August. During theAllied intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions that began in 1918. The initial impetus behind the interventions was to secure munitions and supply depots from falling into the German ...

, ''Centurion'' participated in an exchange of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

with the victorious Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

in October–November. After the destroyer struck a mine near Trebizond on 12 November, she was towed from Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

for permanent repairs by ''Centurion''. In April 1921, the ship was again reduced to reserve, recommissioning on 1 August 1922 before the Chanak Crisis of September. Upon her return home in April 1924, she became the flagship of the Reserve Fleet at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

and participated in a fleet review in Torbay

Torbay is a unitary authority with a borough status in the ceremonial county of Devon, England. It is governed by Torbay Council, based in the town of Torquay, and also includes the towns of Paignton and Brixham. The borough consists of ...

on 26 July. ''Centurion'' was transferred to Chatham Dockyard at the end of the year and remained there through 1925.

In April 1926, the ship was chosen to replace the elderly semi-dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

as the fleet's radio-controlled target ship. The conversion, costing approximately £358,088, began on 14 April at Chatham Dockyard and lasted until July 1927 when she began sea trials. She was laid up in 1931 to cut costs and was decommissioned at Portsmouth on 30 January 1932. The ship was recommissioned in 1933 and was used by the Atlantic Fleet on 1 June. She was used in September for trials with dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s, which made 19 hits out of 48 bombs dropped; a much higher rate than level bombing from medium or high altitudes. ''Centurion'' was refitted between November 1934 – January 1935 to repair the damage inflicted by the fleet.

World War II

In 1939–1940, the ship continued in her prewar role, although she was briefly considered for rearming in May 1940 as an anti-aircraft cruiser in support of the Norway campaign. She then served as a repair ship at Devonport before being converted into a blockship in April 1941. On 14 April,

In 1939–1940, the ship continued in her prewar role, although she was briefly considered for rearming in May 1940 as an anti-aircraft cruiser in support of the Norway campaign. She then served as a repair ship at Devonport before being converted into a blockship in April 1941. On 14 April, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

suggested that a heavy naval bombardment of the Libyan city of Tripoli should be made by the Mediterranean Fleet and followed up by blocking the port with a battleship and the Admiralty suggested and a cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

, but Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, rejected the idea of using one of his active battleships and suggested ''Centurion'' instead. Upon further consideration, he assessed the chance of success as one in ten due to the difficulties of "wedging herself in exactly the right position within point blank range of the enemy guns with enemy dive bombers overhead." The ship was then modified to resemble the battleship , then building at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth.

In 1942, ''Centurion'' was transferred to the

In 1942, ''Centurion'' was transferred to the Eastern Fleet

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

and was detached to the Mediterranean Fleet in May–June to escort Convoy M.W. 11 from Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

to Malta in June as part of Operation Vigorous. She was assigned in the hopes of deceiving the Axis about the presence of an operational battleship; the Italians seem to have seen through the deception by the time the convoy sailed on 13 June, although the Germans were deceived. Two days later, the ship was slightly damaged by near misses when attacked by nine dive bombers; her Oerlikon cannon shot one of them down. ''Centurion'' was scuttled

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vesse ...

as a breakwater during the Invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 ( D-Day) with the ...

off Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors of the amphibious assault component of Operation Overlord during the Second World War.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies of World War II, Allies invaded German military administration in occupied Fra ...

on 9 June 1944 to protect a Mulberry harbour

The Mulberry harbours were two temporary portable harbours developed by the Admiralty (United Kingdom), British Admiralty and War Office during the Second World War to facilitate the rapid offloading of cargo onto beaches during the Allies of ...

built to supply the forces ashore.Hampshire, pp. 139–157; Lenton, p. 574

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Maritimequest HMS Centurion Photo Gallery

Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project – HMS Centurion Crew List

{{DEFAULTSORT:Centurion (1911) King George V-class battleships (1911) Ships built in Plymouth, Devon 1911 ships World War I battleships of the United Kingdom World War II battleships of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean Shipwrecks of France Scuttled vessels of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in June 1944 Ships sunk as breakwaters