Guthlac of Crowland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Saint Guthlac of Crowland (; ; 674714AD) was a Christian

Guthlac was the son of Penwalh or Penwald, a noble of the English kingdom of

Guthlac was the son of Penwalh or Penwald, a noble of the English kingdom of

The 8th-century Latin ''Vita sancti Guthlaci'', written by Felix, describes the entry of the demons into Guthlac's cell:

Felix records Guthlac's foreknowledge of his own death, conversing with angels in his last days. At the moment of death a sweet nectar-like odour emanated from his mouth, as his soul departed from his body in a beam of light while the angels sang. Guthlac had requested a lead coffin and linen winding-sheet from Ecgburh, Abbess of Repton Abbey, so that his funeral rites could be performed by his sister Pega. Arriving the day after his death, she found the island of Crowland filled with the scent of ambrosia. She buried the body on the mound after three days of prayer. A year later Pega had a divine calling to move the tomb and relics to a nearby chapel: Guthlac's body is said to have been discovered uncorrupted, his shroud shining with light. Subsequently Guthlac appeared in a miraculous vision to Æthelbald, prophesying that he would be a future King of Mercia.

The 8th-century Latin ''Vita sancti Guthlaci'', written by Felix, describes the entry of the demons into Guthlac's cell:

Felix records Guthlac's foreknowledge of his own death, conversing with angels in his last days. At the moment of death a sweet nectar-like odour emanated from his mouth, as his soul departed from his body in a beam of light while the angels sang. Guthlac had requested a lead coffin and linen winding-sheet from Ecgburh, Abbess of Repton Abbey, so that his funeral rites could be performed by his sister Pega. Arriving the day after his death, she found the island of Crowland filled with the scent of ambrosia. She buried the body on the mound after three days of prayer. A year later Pega had a divine calling to move the tomb and relics to a nearby chapel: Guthlac's body is said to have been discovered uncorrupted, his shroud shining with light. Subsequently Guthlac appeared in a miraculous vision to Æthelbald, prophesying that he would be a future King of Mercia.

File:Guthlac-Contemplation-BL.jpg, Roundel from ''Guthlac Roll'', 1210: Guthlac in contemplation

File:Guthlac-Chapel-BL.jpg, Roundel from ''Guthlac Roll'', 1210: Guthlac builds a chapel at Crowland

File:Croyland Abbey & Parish Church of Crowland.JPG, Crowland Abbey

File:Croyland Abbey Coat of Arms.JPG, Coat of Arms at Crowland Abbey show scourges and the flaying knives of St Bartholomew

File:Guthlac-Stained-Glass-Crowland-Abbey.jpg, St Guthlac, stained glass, Crowland Abbey

File:Little Cowarne church and graveyard - geograph.org.uk - 1005928.jpg, St Guthlac's Church (12C), Little Cowarne,

Alternative link

via – GoogleBooks. Accessed 7 November 2023.)

PDF file download

link. 400kB.) * * * * * * * *

"Guthlac of Crowland, a Saint for Middle England"

''Fursey Occasional Paper'' No. 3. Norwich, UK: Fursey Pilgrims. pp. 1–36. *Sharma, Manish (2002). "A Reconsideration of ''Guthlac A'': The Extremes of Saintliness". ''Journal of English and Germanic Philology'' 101: 185–200. *Shook, Laurence K. (August 1960). "The Burial Mound in ''Guthlac A''". '' Modern Philology''. 58 (1): 1–10. *Soon Ai, Low (1997). "Mental Culturation in ''Guthlac B''". '' Neophilologus''. 81: 625–636.

The Guthlac Roll, British Library online exhibitionThe Guthlac Roll, full online facsimileSt Guthlac's Cross

Grade II listed site,

CatholicSaints.Info

{{DEFAULTSORT:Guthlac 673 births 714 deaths 7th-century English people 8th-century English people English hermits Eastern Orthodox monks East Anglian saints 8th-century Christian saints Incorrupt saints People from Lincolnshire Angelic visionaries

hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

and saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

from Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

in England. He is particularly venerated in the Fens

The Fens or Fenlands in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a system o ...

of eastern England.

Hagiography

Early life

Guthlac was the son of Penwalh or Penwald, a noble of the English kingdom of

Guthlac was the son of Penwalh or Penwald, a noble of the English kingdom of Mercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

, and his wife Tette. Guthlac's sister is venerated as St Pega. As a young man, Guthlac fought in the army of King Æthelred of Mercia

Æthelred (; died after 704) was king of Mercia from 675 until 704. He was the son of Penda of Mercia and came to the throne in 675, when his brother, Wulfhere of Mercia, died from an illness. Within a year of his accession he invaded Kent, ...

(). He subsequently became a monk at Repton Abbey in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

at the age of 24, under the abbess there (Repton being a double monastery). Two years later he sought to live the life of a hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

, and moved out to the island of Croyland, now called Crowland (in present-day Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

), on St Bartholomew's Day, 699. His early biographer, Felix, writing in the early 8th century, asserts that Guthlac could understand the ('sibilant speech', that is "barbarous language") of Brittonic-speaking demons who haunted him there, only because Guthlac had spent some time in exile among Celtic Britons.

Hermit

Guthlac built a small oratory and cells in the side of a plundered barrow on the island. There he lived until his death on 11 April 714. Felix, writing within living memory of Guthlac, described his hermit's existence: Guthlac suffered from ague and marsh fever.Cultus

Guthlac's pious and holy ascetic life became the talk of the land, and many people visited the hermit during his life to seek spiritual guidance from him. He gave sanctuary to Æthelbald, future king ofMercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

, who was fleeing from his cousin Ceolred (). Guthlac predicted that Æthelbald would become king, and Æthelbald promised to build him an abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christians, Christian monks and nun ...

if his prophecy became true. Æthelbald indeed became king (), and even though Guthlac had died two years before, Æthelbald kept his word and started to build Crowland Abbey on St Bartholomew's Day, 716. Guthlac's feast day is celebrated on 11 April.

The 8th-century Latin ''Vita sancti Guthlaci'', written by Felix, describes the entry of the demons into Guthlac's cell:

Felix records Guthlac's foreknowledge of his own death, conversing with angels in his last days. At the moment of death a sweet nectar-like odour emanated from his mouth, as his soul departed from his body in a beam of light while the angels sang. Guthlac had requested a lead coffin and linen winding-sheet from Ecgburh, Abbess of Repton Abbey, so that his funeral rites could be performed by his sister Pega. Arriving the day after his death, she found the island of Crowland filled with the scent of ambrosia. She buried the body on the mound after three days of prayer. A year later Pega had a divine calling to move the tomb and relics to a nearby chapel: Guthlac's body is said to have been discovered uncorrupted, his shroud shining with light. Subsequently Guthlac appeared in a miraculous vision to Æthelbald, prophesying that he would be a future King of Mercia.

The 8th-century Latin ''Vita sancti Guthlaci'', written by Felix, describes the entry of the demons into Guthlac's cell:

Felix records Guthlac's foreknowledge of his own death, conversing with angels in his last days. At the moment of death a sweet nectar-like odour emanated from his mouth, as his soul departed from his body in a beam of light while the angels sang. Guthlac had requested a lead coffin and linen winding-sheet from Ecgburh, Abbess of Repton Abbey, so that his funeral rites could be performed by his sister Pega. Arriving the day after his death, she found the island of Crowland filled with the scent of ambrosia. She buried the body on the mound after three days of prayer. A year later Pega had a divine calling to move the tomb and relics to a nearby chapel: Guthlac's body is said to have been discovered uncorrupted, his shroud shining with light. Subsequently Guthlac appeared in a miraculous vision to Æthelbald, prophesying that he would be a future King of Mercia.

Legacy

The cult of Guthlac continued amongst a monastic community at Crowland, with the eventual foundation of Crowland Abbey as aBenedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

establishment in 971. A series of fires at the abbey mean that few records survive from before the 12th century. It is known that in 1136 the remains of Guthlac were moved once more, and that finally in 1196 his shrine was placed above the main altar.

The Yorkshire village of Golcar on the outskirts of Huddersfield is named after St Guthlac, who preached in the area during the 8th century. The name of the village is recorded in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

of 1086 as Goullakarres. Scholar of early modern British history, Paul Cavill discusses in a 2015 essay the origins of the name ''Guthlac'' and whether his hagiographer Felix intended to convey that the saint was named after his tribe and land, or if, instead, these were named in honour of Guthlac.

It has been proposed that Shakespeare drew on a lost play based on St Guthlac when writing ''The Tempest

''The Tempest'' is a Shakespeare's plays, play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, th ...

''.

Historiography

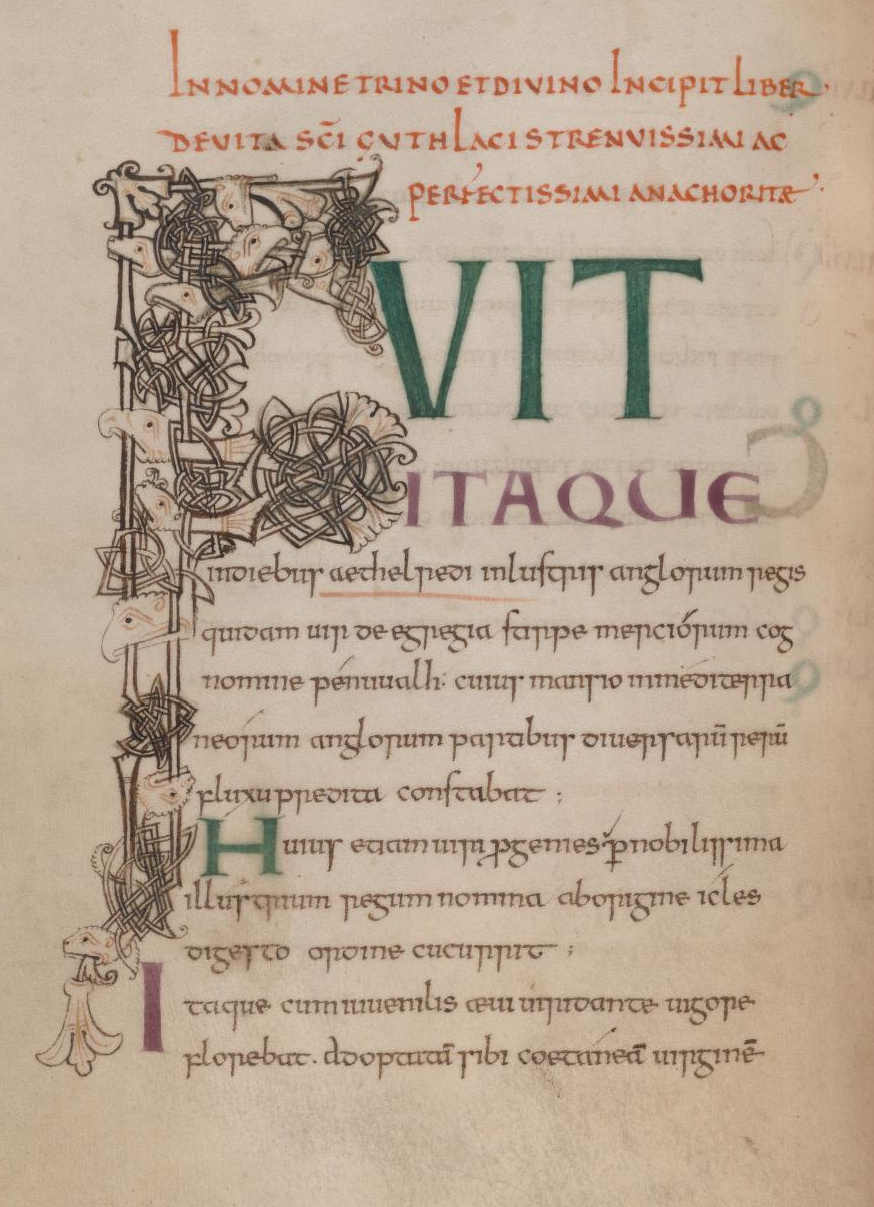

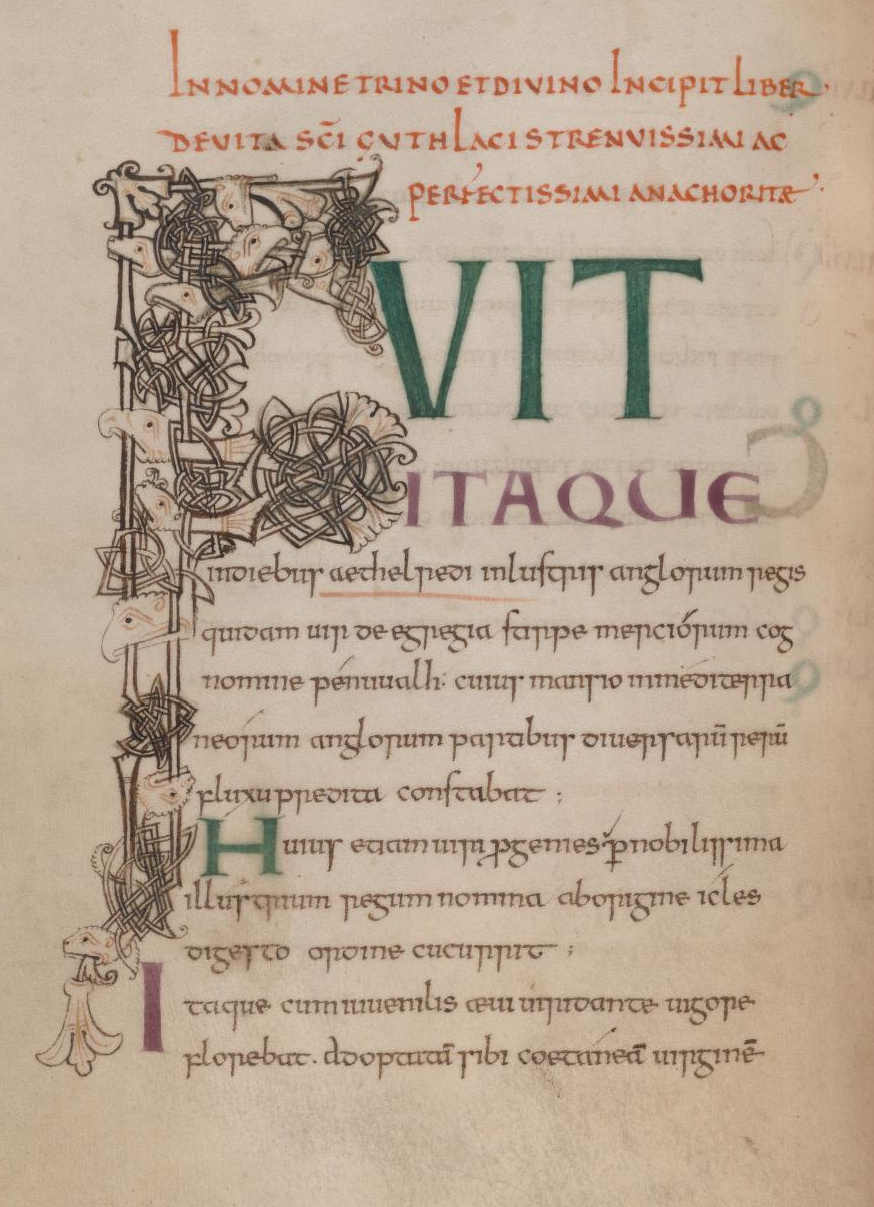

His firsthagiographer

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an wiktionary:adulatory, adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religi ...

, Felix of Crowland composed Guthlac's within a decade or two of the hermits's death. Based on textual evidence within the ''vita'', the medieval historian Bertram Colgrave suggests it was most likely written between 730 and 740. Its latest possible date of composition is 749 when its commissioner, Ælfwald of East Anglia diedFelix states in his prologue that he is writing at his king's, Ælfwald's, command. It was written in Anglo-Latin, and follows the traditional patterns for hagiographies. The survival of many early manuscript copies and the use of Felix's text as the source for later vernacular Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

-language adaptations attest the work's influence in the spread of Guthlac's cult.

A short Old English sermon (Vercelli

Vercelli (; ) is a city and ''comune'' of 46,552 inhabitants (January 1, 2017) in the Province of Vercelli, Piedmont, northern Italy. One of the oldest urban sites in northern Italy, it was founded, according to most historians, around 600 BC.

...

XXIII) and a longer prose translation into Old English are both based on Felix's ''Vita''. There are also two poems in Old English known as '' Guthlac A'' and '' Guthlac B'', part of the tenth-century Exeter Book, the oldest surviving collection of English poetry. The relationship of ''Guthlac A'' to Felix's ''Vita'' is debated, but ''Guthlac B'' is based on Felix's account of the saint's death.

The story of Guthlac is told pictorially in the ''Guthlac Roll'', a set of detailed illustrations of the early 13th century. This is held in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. Based in London, it is one of the largest libraries in the world, with an estimated collection of between 170 and 200 million items from multiple countries. As a legal deposit li ...

, with copies on display in Crowland Abbey.

Another account, also dating from after the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

, was included in the ''Ecclesiastical History'' of Orderic Vitalis

Orderic Vitalis (; 16 February 1075 – ) was an English chronicler and Benedictine monk who wrote one of the great contemporary chronicles of 11th- and 12th-century Normandy and Anglo-Norman England.Hollister ''Henry I'' p. 6 Working out of ...

, which like the ''Guthlac Roll'' was commissioned by the Abbot of Crowland Abbey. At a time when it was being challenged by the crown, the Abbey relied significantly on the cult of Guthlac, which made it a place of pilgrimage and healing. That is reflected in a shift in the emphasis from the earlier accounts of Felix and others. The post-conquest accounts portray him as a defender of the church rather than a saintly ascetic; instead of dwelling in an ancient burial mound, they depict Guthlac overseeing the building of a brick and stone chapel on the site of the abbey.

Churches and dedications

Churches and other places named for Guthlac are predominantly located inthe Fens

The Fens or Fenlands in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a system o ...

and East Midlands of England, where he was an important saint into Norman times.

The Benedictine St Guthlac's Priory was founded early in the 12th century in Hereford

Hereford ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of the ceremonial county of Herefordshire, England. It is on the banks of the River Wye and lies east of the border with Wales, north-west of Gloucester and south-west of Worcester. With ...

, near the still extant church of St Guthlac at Little Cowarne. The priory was ruined in , and relocated to a site near the present St. Guthlac Street, Hereford. It was disestablished during the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538.

St Guthlac Fellowship

Formed in 1987, St Guthlac's Fellowship is an association of churches sharing a dedication to St Guthlac. Its fellows, all Anglican churches except where noted, are listed below: * St Guthlac's Church, Astwick inBedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated ''Beds'') is a Ceremonial County, ceremonial county in the East of England. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the north-east, Hertfordshire to the south and the south-east, and Buckin ...

* St Guthlac's Church, Little Cowarne in Herefordshire

Herefordshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England, bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh ...

* St Guthlac's Church, Passenham in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire ( ; abbreviated Northants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshi ...

Located in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

:

* St Guthlac's Church, Branston

* St Guthlac's Church, Knighton, Leicester

* St Guthlac's Church, Stathern

Located in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

:

* Crowland Abbey, in Crowland

Crowland (modern usage) or Croyland (medieval era name and the one still in ecclesiastical use; cf. ) is a town and civil parish in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated between Peterborough and Spalding. Crowland ...

* All Saints' Parish Church, Branston

* Our Lady and St Guthlac Church, Deeping St James – a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

church

* St Guthlac's Church, Fishtoft

* St Guthlac's Church, Little Ponton

* St Guthlac's Church, Market Deeping

Gallery

Herefordshire

Herefordshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England, bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh ...

File:St. Guthlac, the parish church of Astwick - geograph.org.uk - 1281480.jpg, St Guthlac's Church, Astwick, Bedfordshire

Image:St Guthlac's Church, Stathern.jpg, St Guthlac's Church, Stathern, Leicestershire

Image:St Guthlacs church.jpg, St Guthlac's Church, Market Deeping, Lincolnshire

File:St.Guthlac's church, Little Ponton, Lincs. - geograph.org.uk - 144537.jpg, St Guthlac's Church, Little Ponton, Lincolnshire

File:St.Guthlac's church, Fishtoft - geograph.org.uk - 147445.jpg, St Guthlac's Church, Fishtoft, Lincolnshire

File:Church of St Guthlac, Branston - geograph.org.uk - 1745446.jpg, All Saints' Church, Branston, Lincolnshire

File:St. Guthlac's, Passenham - geograph.org.uk - 1011237.jpg, St Guthlac's Church, Passenham, Northamptonshire

References

Works cited

Primary sources

* Felix arly 8th-century Latin prose. ife of St Guthlac. Translations * ** *Alternative link

via – GoogleBooks. Accessed 7 November 2023.)

Secondary sources

* * * * * * * (DirecPDF file download

link. 400kB.) * * * * * * * *

Further reading

Primary hagiographical materials

*Old English prose translation–adaptation (late 9th or early 10th century) of the ''Life of St Guthlac'' by Felix: **Gonser, P., ed. (1909). "Das angelsächsische Prosa-Leben des heiligen Guthlac". ''Anglistische Forschungen'' 27. Heidelberg. *Two chapters from the Old English prose adaptation as incorporated into Vercelli Homily 23 **Scragg, D. G., ed. ( 1992). ''The Vercelli Homilies and Related Texts''. EETS 300. Oxford: University Press. *'' Guthlac A'' and '' Guthlac B'' (Old English poems): **Roberts, Jane, ed. (1979). ''The Guthlac Poems of the Exeter Book''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. **Krapp, G. and E. V. K. Dobbie, eds. (1936). ''The Exeter Book''. Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3. pp. 49–88. **Bradley, S. A. J. (tr.) ''Anglo-Saxon Poetry''. London: Everyman, 1982. ** *''Harley Roll'' or ''Guthlac Roll'' (BL, Harleian Roll Y.6) **Warner, G. F., ed. (1928). ''The Guthlac Roll''. Roxburghe Club. 25 plates in facsimileScholarly works

*Cubitt, Catherine (2000). "Memory and narrative in the cult of early Anglo-Saxon saints". In Yitzhak Hen; Matthew Innes (eds.). ''The Uses of the Past in the Early Middle Ages''. pp.2966. Cambridge University Press. . . *Nuding, Emma (2022). "Gazing on Guthlacian Reliques: John Clare's Pilgrim-Tourists and St Guthlac of Crowland". ''John Clare Society Journal''. 41: 25–44. *Nuding, Emma (2023). "Monastic Ecopoetics in the Thirteenth-Century Fens: Henry de Avranches' ''Vita Guthlaci''". ''Medieval Ecocriticisms'' 3. *Olsen, Alexandra Hennessey (1981). ''Guthlac of Croyland: A Study of Heroic Hagiography''. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America. . *Powell, Stephen D. (1998). "The Journey Forth: Elegiac Consolation in ''Guthlac B''." ''English Studies''. 79: 489–500. *Roberts, Jane (1970). "An inventory of early Guthlac materials". ''Mediaeval Studies''. 32: 193–233. *Roberts, Jane (1986). "The Old English Prose Translation of Felix's ''Vita Sancti Guthlaci''". In Paul E. Szarmach (ed). ''Studies in Earlier Old English Prose: Sixteen Original Contributions''. Albany, New York, US: State University of New York Press. pp. 363–379. *Roberts, Jane (2009)"Guthlac of Crowland, a Saint for Middle England"

''Fursey Occasional Paper'' No. 3. Norwich, UK: Fursey Pilgrims. pp. 1–36. *Sharma, Manish (2002). "A Reconsideration of ''Guthlac A'': The Extremes of Saintliness". ''Journal of English and Germanic Philology'' 101: 185–200. *Shook, Laurence K. (August 1960). "The Burial Mound in ''Guthlac A''". '' Modern Philology''. 58 (1): 1–10. *Soon Ai, Low (1997). "Mental Culturation in ''Guthlac B''". '' Neophilologus''. 81: 625–636.

External links

*The Guthlac Roll, British Library online exhibition

Grade II listed site,

English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, a battlefield, medieval castles, Roman forts, historic industrial sites, Lis ...

CatholicSaints.Info

{{DEFAULTSORT:Guthlac 673 births 714 deaths 7th-century English people 8th-century English people English hermits Eastern Orthodox monks East Anglian saints 8th-century Christian saints Incorrupt saints People from Lincolnshire Angelic visionaries