Greek Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Greek Civil War ( el, Оҝ EОјПҶПҚО»О№ОҝПӮ пҝҪПҢО»ОөОјОҝПӮ}, ''o EmfГҪlios'' 'PГіlemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established

In mid-1943 the animosity between ELAS and the other movements erupted into armed conflict. The communists and EAM accused EDES of being traitors and collaborators, and vice versa. Other smaller groups, such as EKKA, continued the anti-occupation fight with sabotage and other actions. They declined to join the ranks of ELAS. While some organizations accepted assistance from the Nazis in their operations against ELAS, the great majority of the population refused any form of cooperation with the occupation authorities. By early 1944, after a British-negotiated ceasefire (the Plaka Agreement), ELAS had destroyed EKKA and confined EDES to a small part of

In mid-1943 the animosity between ELAS and the other movements erupted into armed conflict. The communists and EAM accused EDES of being traitors and collaborators, and vice versa. Other smaller groups, such as EKKA, continued the anti-occupation fight with sabotage and other actions. They declined to join the ranks of ELAS. While some organizations accepted assistance from the Nazis in their operations against ELAS, the great majority of the population refused any form of cooperation with the occupation authorities. By early 1944, after a British-negotiated ceasefire (the Plaka Agreement), ELAS had destroyed EKKA and confined EDES to a small part of

In March 1944, EAM established the Political Committee of National Liberation (''Politiki Epitropi Ethnikis Apeleftherosis'', or PEEA), in effect a third Greek government to rival those in Athens and Cairo "to intensify the struggle against the conquerors... for full national liberation, for the consolidation of the independence and integrity of our country... and for the annihilation of domestic Fascism and armed traitor formations." PEEA was dominated by, but not composed exclusively of Communists.

The moderate aims of the PEEA (known as "ОәП…ОІОӯПҒОҪО·ПғО· П„ОҝП… ОІОҝП…ОҪОҝПҚ", "the Mountain Government") aroused support even among Greeks in exile. In April 1944 the Egypt based

In March 1944, EAM established the Political Committee of National Liberation (''Politiki Epitropi Ethnikis Apeleftherosis'', or PEEA), in effect a third Greek government to rival those in Athens and Cairo "to intensify the struggle against the conquerors... for full national liberation, for the consolidation of the independence and integrity of our country... and for the annihilation of domestic Fascism and armed traitor formations." PEEA was dominated by, but not composed exclusively of Communists.

The moderate aims of the PEEA (known as "ОәП…ОІОӯПҒОҪО·ПғО· П„ОҝП… ОІОҝП…ОҪОҝПҚ", "the Mountain Government") aroused support even among Greeks in exile. In April 1944 the Egypt based

The demonstration involved at least 200,000 people marching in

The demonstration involved at least 200,000 people marching in  At the beginning the government had only a few policemen and gendarmes, some militia units, the

At the beginning the government had only a few policemen and gendarmes, some militia units, the

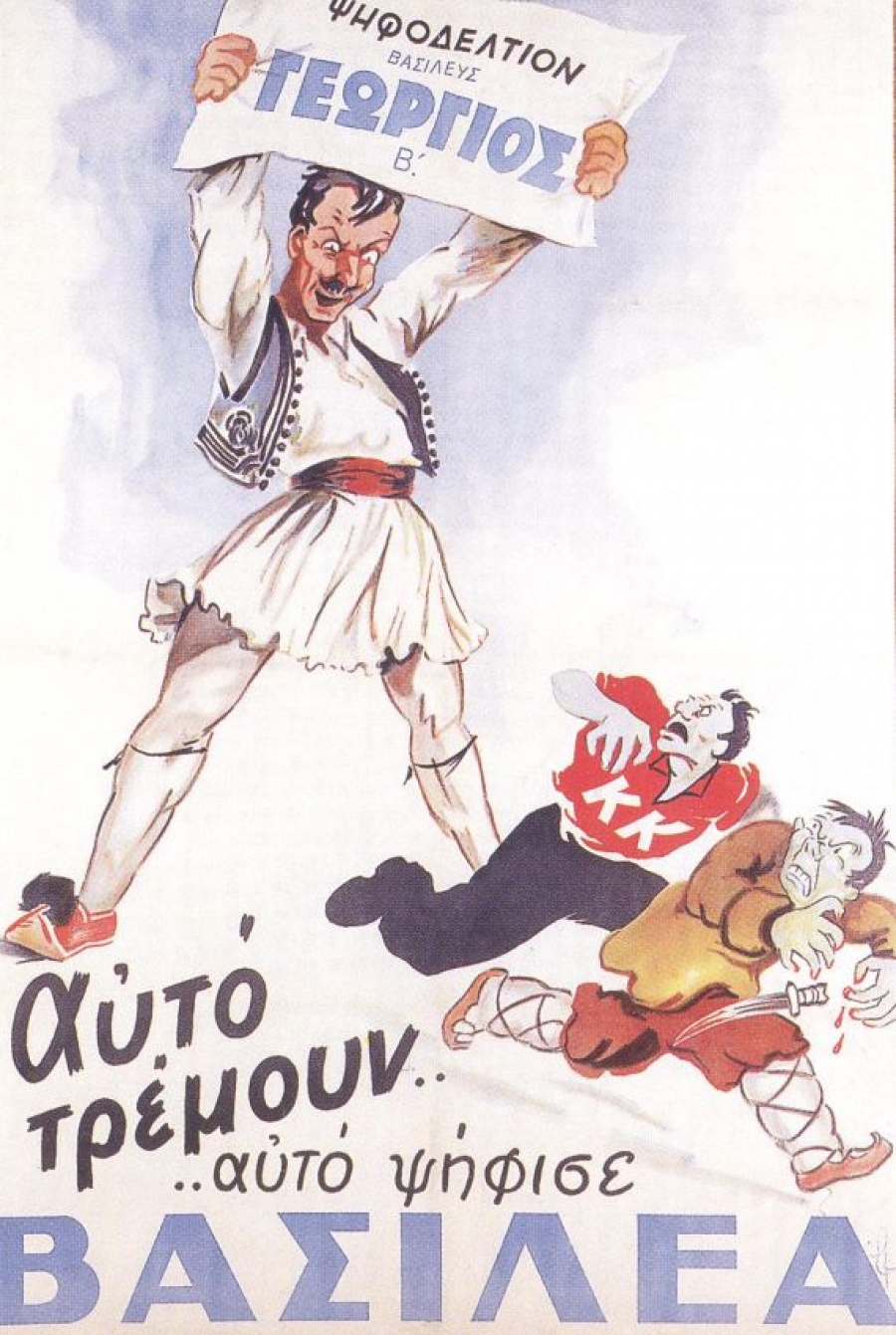

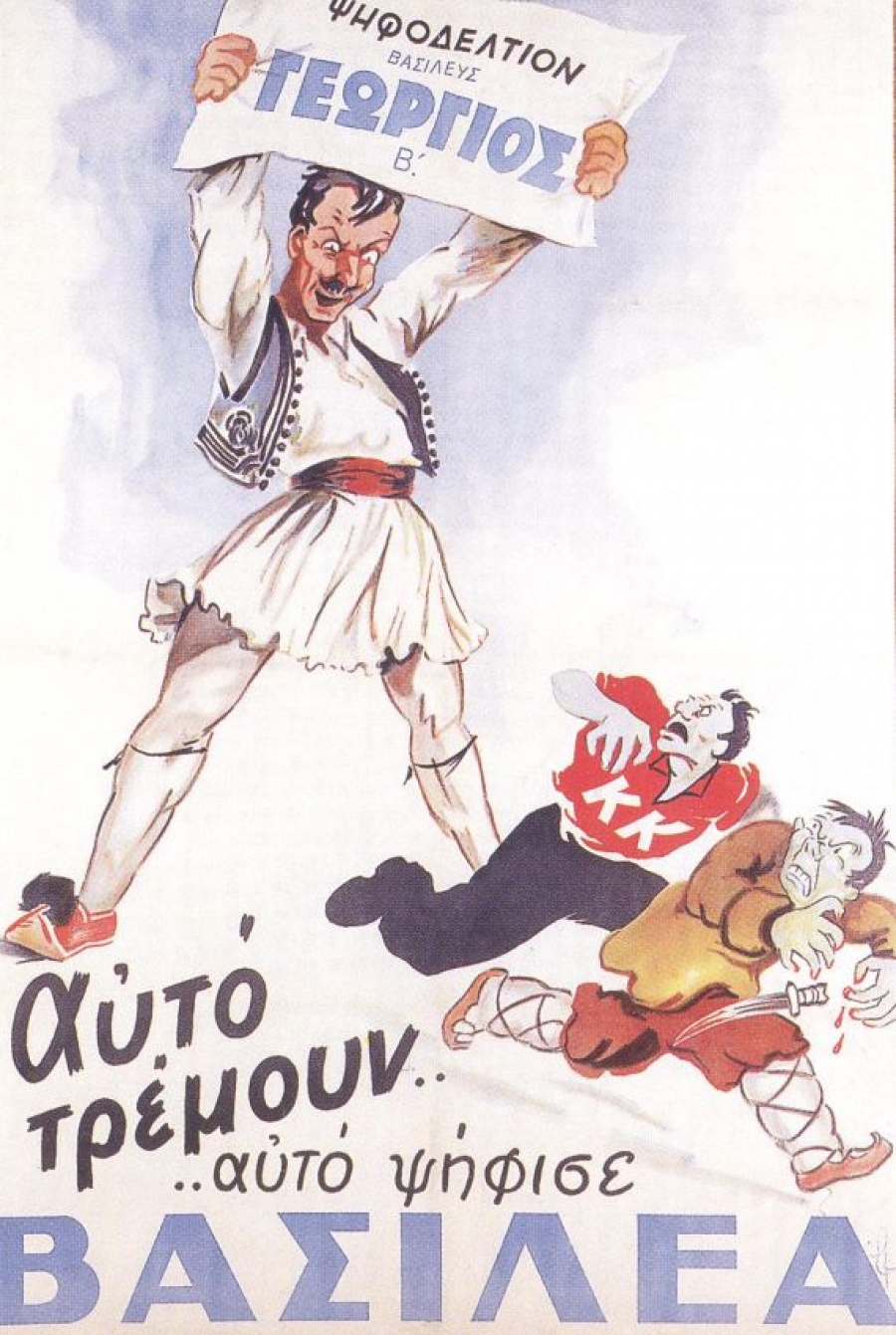

In February 1945, the various Greek parties signed the Treaty of Varkiza, with the support of all the Allies. It provided for the complete demobilisation of the ELAS and all other paramilitary groups, amnesty for only political offenses, a referendum on the monarchy and a general election to be held as soon as possible. The KKE remained legal and its leader, Nikolaos Zachariadis, who returned from Germany in April 1945, said that the KKE's objective was now for a "people's democracy" to be achieved by peaceful means. There were dissenters such as former ELAS leader

In February 1945, the various Greek parties signed the Treaty of Varkiza, with the support of all the Allies. It provided for the complete demobilisation of the ELAS and all other paramilitary groups, amnesty for only political offenses, a referendum on the monarchy and a general election to be held as soon as possible. The KKE remained legal and its leader, Nikolaos Zachariadis, who returned from Germany in April 1945, said that the KKE's objective was now for a "people's democracy" to be achieved by peaceful means. There were dissenters such as former ELAS leader  Between 1945 and 1946, anticommunist forces allegedly killed about 1,190 communist civilians and tortured many others. Entire villages that had helped the partisans were attacked. The anticommunist forces are claimed to have admitted that they were "retaliating" for their suffering under ELAS rule. The reign of "White Terror (Greece), White Terror" led many ex-ELAS members to form self-defence troops without any KKE approval.

The KKE soon reversed its former political position, as relations between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies deteriorated. With the onset of the

Between 1945 and 1946, anticommunist forces allegedly killed about 1,190 communist civilians and tortured many others. Entire villages that had helped the partisans were attacked. The anticommunist forces are claimed to have admitted that they were "retaliating" for their suffering under ELAS rule. The reign of "White Terror (Greece), White Terror" led many ex-ELAS members to form self-defence troops without any KKE approval.

The KKE soon reversed its former political position, as relations between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies deteriorated. With the onset of the

Fighting resumed in March 1946, as a group of 30 ex-ELAS members attacked a police station in the village of Litochoro, killing the policemen, the night before the elections. The next day, the ''Rizospastis'', the KKE's official newspaper, announced, "Authorities and gangs fabricate alleged communist attacks". Armed bands of ELAS' veterans were then infiltrating Greece through mountainous regions near the Yugoslav and Albanian borders; they were now organized as the

Fighting resumed in March 1946, as a group of 30 ex-ELAS members attacked a police station in the village of Litochoro, killing the policemen, the night before the elections. The next day, the ''Rizospastis'', the KKE's official newspaper, announced, "Authorities and gangs fabricate alleged communist attacks". Armed bands of ELAS' veterans were then infiltrating Greece through mountainous regions near the Yugoslav and Albanian borders; they were now organized as the  By late 1946, the DSE was able to deploy about 16,000 partisans, including 5,000 in the Peloponnese and other areas of Greece. According to the DSE, its fighters "resisted the reign of terror that right-wing gangs conducted across Greece". In the Peloponnese especially, local party officials, headed by Vangelis Rogakos, had established a plan long before the decision to go to guerrilla war under which the numbers of partisans operating in the mainland would be inversely proportional to the number of soldiers that the enemy would concentrate in the region. According to the study, the DSE III Division in the Peloponnese numbered between 1,000 and 5,000 fighters in early 1948.''The Civil War in Peloponnese'', A. Kamarinos

Rural peasants were caught in the crossfire. When DSE partisans entered a village asking for supplies, citizens were supportive (in previous years, EAM could count on two million members across the whole country) or did not resist. When Hellenic Army, government troops arrived at the same village, citizens who had supplied the partisans were immediately denounced as communist sympathizers and usually imprisoned or exiled. In rural areas, the government also used a strategy, which had been advised by US advisers, of evacuating villages under the pretext that they were under direct threat of communist attack. That would deprive the partisans of supplies and recruits and simultaneously raise antipathy towards them.

The Greek Army now numbered about 90,000 men and was gradually being put on a more professional footing. The task of re-equipping and training the army had been carried out by its fellow Western Allies. By early 1947, however, Britain, which had spent ВЈ85 million in Greece since 1944, could no longer afford this burden. US President Harry S. Truman announced that the United States would step in to support the Greek government against Communist pressure. That began a long and troubled relationship between Greece and the United States. For several decades to come, the US ambassador advised the king on important issues, such as the appointment of the prime minister.

Through 1947, the scale of fighting increased. The DSE launched large-scale attacks on towns across northern Epirus,

By late 1946, the DSE was able to deploy about 16,000 partisans, including 5,000 in the Peloponnese and other areas of Greece. According to the DSE, its fighters "resisted the reign of terror that right-wing gangs conducted across Greece". In the Peloponnese especially, local party officials, headed by Vangelis Rogakos, had established a plan long before the decision to go to guerrilla war under which the numbers of partisans operating in the mainland would be inversely proportional to the number of soldiers that the enemy would concentrate in the region. According to the study, the DSE III Division in the Peloponnese numbered between 1,000 and 5,000 fighters in early 1948.''The Civil War in Peloponnese'', A. Kamarinos

Rural peasants were caught in the crossfire. When DSE partisans entered a village asking for supplies, citizens were supportive (in previous years, EAM could count on two million members across the whole country) or did not resist. When Hellenic Army, government troops arrived at the same village, citizens who had supplied the partisans were immediately denounced as communist sympathizers and usually imprisoned or exiled. In rural areas, the government also used a strategy, which had been advised by US advisers, of evacuating villages under the pretext that they were under direct threat of communist attack. That would deprive the partisans of supplies and recruits and simultaneously raise antipathy towards them.

The Greek Army now numbered about 90,000 men and was gradually being put on a more professional footing. The task of re-equipping and training the army had been carried out by its fellow Western Allies. By early 1947, however, Britain, which had spent ВЈ85 million in Greece since 1944, could no longer afford this burden. US President Harry S. Truman announced that the United States would step in to support the Greek government against Communist pressure. That began a long and troubled relationship between Greece and the United States. For several decades to come, the US ambassador advised the king on important issues, such as the appointment of the prime minister.

Through 1947, the scale of fighting increased. The DSE launched large-scale attacks on towns across northern Epirus,

In September 1947, however, the KKE's leadership decided to move from guerrilla tactics to fullscale conventional war despite the opposition of Vafiadis. In December, the KKE announced the formation of a Provisional Democratic Government, with Vafiadis as prime minister; that led the Athens government to ban the KKE. No foreign government recognized this government. The new strategy led the DSE into costly attempts to seize a major town as its seat of government, and in December 1947, 1200 DSE fighters were killed at a set battle around Battle of Konitsa, Konitsa. At the same time, the strategy forced the government to increase the size of the army. With control of the major cities, the government cracked down on KKE members and sympathizers, many of whom were imprisoned on the island of Makronisos.

In September 1947, however, the KKE's leadership decided to move from guerrilla tactics to fullscale conventional war despite the opposition of Vafiadis. In December, the KKE announced the formation of a Provisional Democratic Government, with Vafiadis as prime minister; that led the Athens government to ban the KKE. No foreign government recognized this government. The new strategy led the DSE into costly attempts to seize a major town as its seat of government, and in December 1947, 1200 DSE fighters were killed at a set battle around Battle of Konitsa, Konitsa. At the same time, the strategy forced the government to increase the size of the army. With control of the major cities, the government cracked down on KKE members and sympathizers, many of whom were imprisoned on the island of Makronisos.

Despite setbacks, such as the fighting at Konitsa, the DSE reached the height of its power in 1948, extending its operations to Attica, within 20 km of Athens. It drew on more than 20,000 fighters, both men and women, and a network of sympathizers and informants in every village and suburb.

Among analysts emphasising the KKE's perceived control and guidance by foreign powers, such as the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, some estimate that of the DSE's 20,000 fighters, 14,000 were

Despite setbacks, such as the fighting at Konitsa, the DSE reached the height of its power in 1948, extending its operations to Attica, within 20 km of Athens. It drew on more than 20,000 fighters, both men and women, and a network of sympathizers and informants in every village and suburb.

Among analysts emphasising the KKE's perceived control and guidance by foreign powers, such as the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, some estimate that of the DSE's 20,000 fighters, 14,000 were

Yugoslavia had been the Greek Communists' main supporter from the years of the occupation. The KKE thus had to choose between its loyalty to the Soviet Union and its relations with its closest ally. After some internal conflict, the great majority, led by party secretary Nikolaos Zachariadis, chose to follow the Soviet Union. In January 1949, Vafiadis himself was accused of "Titoism" and removed from his political and military positions, to be replaced by Zachariadis.

After a year of increasing acrimony, Tito closed the Yugoslav border to the DSE in July 1949, and disbanded its camps inside Yugoslavia. The DSE was still able to use Albanian border territories, a poor alternative. Within the Greek Communist Party, the split with Tito also sparked a witch hunt for "Titoites" that demoralised and disorganised the ranks of the DSE and sapped support for the KKE in urban areas.

In summer 1948, DSE Division III in the Peloponnese suffered a huge defeat. Lacking ammunition support from DSE headquarters and having failed to capture government ammunition depots at Zacharo in the western Peloponnese, its 20,000 fighters were doomed. The majority (including the commander of the Division, Vangelis Rogakos) were killed in battle with nearly 80,000 National Army troops. The National Army's strategic plan, codenamed "Operation Peristera, Peristera" (the Greek word for "dove (bird)"), was successful. A number of other civilians were sent to prison camps for helping Communists. The Peloponnese was now governed by paramilitary groups fighting alongside the National Army. To terrify urban areas assisting DSE's III Division, the forces decapitated a number of dead fighters and placed them in central squares. Following defeat in southern Greece, the DSE continued to operate in northern Greece and some islands, but it was a greatly weakened force facing significant obstacles both politically and militarily.

At the same time, the National Army found a talented commander in General Alexander Papagos, commander of the Greek army during the Greco-Italian War. In August 1949, Papagos launched a major counteroffensive against DSE forces in northern Greece, codenamed "Operation Pyrsos, Operation Pyrsos/Torch". The campaign was a victory for the National Army and resulted in heavy losses for the DSE. The DSE army was now no longer able to sustain resistance in pitched battles. By September 1949, the main body of DSE divisions defending Grammos and Vitsi, the two key positions in northern Greece for the DSE, had retreated to Albania. Two main groups remained within the borders, trying to reconnect with scattered DSE fighters largely in Central Greece.

These groups, numbering 1,000 fighters, left Greece by the end of September 1949. The main body of the DSE, accompanied by its HQ, after discussion with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and other Communist governments, was moved to Tashkent in the Soviet Union. They were to remain there, in military encampments, for three years. Other older combatants, alongside injured fighters, women and children, were relocated to European socialist states. On October 16, Zachariadis announced a "temporary ceasefire to prevent the complete annihilation of Greece"; the ceasefire marked the end of the Greek Civil War.

Almost 100,000 ELAS fighters and Communist sympathizers serving in DSE ranks were imprisoned, exiled, or executed. That deprived the DSE of the principal force still able to support its fight. According to some historians, the KKE's major supporter and supplier had always been Tito, and it was the rift between Tito and the KKE that marked the real demise of the party's efforts to assert power.

Western anti-Communist governments allied to Greece saw the end of the Greek Civil War as a victory in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. Communists countered that the Soviets never actively supported the Greek Communist efforts to seize power in Greece. Both sides had, at differing junctures, nevertheless looked to an external superpower for support.

Yugoslavia had been the Greek Communists' main supporter from the years of the occupation. The KKE thus had to choose between its loyalty to the Soviet Union and its relations with its closest ally. After some internal conflict, the great majority, led by party secretary Nikolaos Zachariadis, chose to follow the Soviet Union. In January 1949, Vafiadis himself was accused of "Titoism" and removed from his political and military positions, to be replaced by Zachariadis.

After a year of increasing acrimony, Tito closed the Yugoslav border to the DSE in July 1949, and disbanded its camps inside Yugoslavia. The DSE was still able to use Albanian border territories, a poor alternative. Within the Greek Communist Party, the split with Tito also sparked a witch hunt for "Titoites" that demoralised and disorganised the ranks of the DSE and sapped support for the KKE in urban areas.

In summer 1948, DSE Division III in the Peloponnese suffered a huge defeat. Lacking ammunition support from DSE headquarters and having failed to capture government ammunition depots at Zacharo in the western Peloponnese, its 20,000 fighters were doomed. The majority (including the commander of the Division, Vangelis Rogakos) were killed in battle with nearly 80,000 National Army troops. The National Army's strategic plan, codenamed "Operation Peristera, Peristera" (the Greek word for "dove (bird)"), was successful. A number of other civilians were sent to prison camps for helping Communists. The Peloponnese was now governed by paramilitary groups fighting alongside the National Army. To terrify urban areas assisting DSE's III Division, the forces decapitated a number of dead fighters and placed them in central squares. Following defeat in southern Greece, the DSE continued to operate in northern Greece and some islands, but it was a greatly weakened force facing significant obstacles both politically and militarily.

At the same time, the National Army found a talented commander in General Alexander Papagos, commander of the Greek army during the Greco-Italian War. In August 1949, Papagos launched a major counteroffensive against DSE forces in northern Greece, codenamed "Operation Pyrsos, Operation Pyrsos/Torch". The campaign was a victory for the National Army and resulted in heavy losses for the DSE. The DSE army was now no longer able to sustain resistance in pitched battles. By September 1949, the main body of DSE divisions defending Grammos and Vitsi, the two key positions in northern Greece for the DSE, had retreated to Albania. Two main groups remained within the borders, trying to reconnect with scattered DSE fighters largely in Central Greece.

These groups, numbering 1,000 fighters, left Greece by the end of September 1949. The main body of the DSE, accompanied by its HQ, after discussion with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and other Communist governments, was moved to Tashkent in the Soviet Union. They were to remain there, in military encampments, for three years. Other older combatants, alongside injured fighters, women and children, were relocated to European socialist states. On October 16, Zachariadis announced a "temporary ceasefire to prevent the complete annihilation of Greece"; the ceasefire marked the end of the Greek Civil War.

Almost 100,000 ELAS fighters and Communist sympathizers serving in DSE ranks were imprisoned, exiled, or executed. That deprived the DSE of the principal force still able to support its fight. According to some historians, the KKE's major supporter and supplier had always been Tito, and it was the rift between Tito and the KKE that marked the real demise of the party's efforts to assert power.

Western anti-Communist governments allied to Greece saw the end of the Greek Civil War as a victory in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. Communists countered that the Soviets never actively supported the Greek Communist efforts to seize power in Greece. Both sides had, at differing junctures, nevertheless looked to an external superpower for support.

On April 21, 1967, a group of rightist and anti-communist army officers executed a ''coup d'Г©tat'' and seized power from the government, using the political instability and tension of the time as a pretext. The leader of the coup, Georgios Papadopoulos, George Papadopoulos, was a member of the right-wing military organization Ieros Desmos Ellinon Axiomatikon, IDEA ("Sacred Bond of Greek Officers"), and the subsequent military regime (later referred to as the Greek military junta of 1967вҖ“74, Regime of the Colonels) lasted until 1974.

After the collapse of the military junta, a conservative government under Constantine Karamanlis led to the abolition of monarchy, the legalization of the KKE and a new Constitution of Greece, constitution, which guaranteed political freedoms, individual rights and free elections. In 1981, in a major turning point in Greek history, the centre-left government of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) allowed a number of DSE veterans who had taken refuge in communist countries to return to Greece and reestablish their former estates, which greatly helped to diminish the consequences of the Civil War in Greek society. The PASOK administration also offered state pensions to former partisans of the anti-Nazi resistance; Markos Vafiadis was honorarily elected as member of the Greek parliament under PASOK's flag.

In 1989, the coalition government between Nea Dimokratia and the Coalition of Left and Progress (SYNASPISMOS), in which the KKE was for a period the major force, suggested a law that was passed unanimously by the Greek Parliament, formally recognizing the 1946вҖ“1949 war as a

On April 21, 1967, a group of rightist and anti-communist army officers executed a ''coup d'Г©tat'' and seized power from the government, using the political instability and tension of the time as a pretext. The leader of the coup, Georgios Papadopoulos, George Papadopoulos, was a member of the right-wing military organization Ieros Desmos Ellinon Axiomatikon, IDEA ("Sacred Bond of Greek Officers"), and the subsequent military regime (later referred to as the Greek military junta of 1967вҖ“74, Regime of the Colonels) lasted until 1974.

After the collapse of the military junta, a conservative government under Constantine Karamanlis led to the abolition of monarchy, the legalization of the KKE and a new Constitution of Greece, constitution, which guaranteed political freedoms, individual rights and free elections. In 1981, in a major turning point in Greek history, the centre-left government of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) allowed a number of DSE veterans who had taken refuge in communist countries to return to Greece and reestablish their former estates, which greatly helped to diminish the consequences of the Civil War in Greek society. The PASOK administration also offered state pensions to former partisans of the anti-Nazi resistance; Markos Vafiadis was honorarily elected as member of the Greek parliament under PASOK's flag.

In 1989, the coalition government between Nea Dimokratia and the Coalition of Left and Progress (SYNASPISMOS), in which the KKE was for a period the major force, suggested a law that was passed unanimously by the Greek Parliament, formally recognizing the 1946вҖ“1949 war as a

online

* Iatrides, John O. "George F. Kennan and the birth of containment: the Greek test case." ''World Policy Journal'' 22.3 (2005): 126вҖ“145

online

* Jones, Howard. '' 'A New Kind of War' AmericaвҖҷs Global Strategy and the Truman Doctrine in Greece'' (1989) * Kalyvas, S.N. ''The Logic of Violence in Civil War'', Cambridge, 2006 * Karpozilos, Kostis. "The defeated of the Greek Civil War: From fighters to political refugees in the Cold War." ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' 16.3 (2014): 62вҖ“87

online

* Koumas, Manolis. "Cold War Dilemmas, Superpower Influence, and Regional Interests: Greece and the Palestinian Question, 1947вҖ“1949." ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' 19.1 (2017): 99вҖ“124. * Kousoulas, D. G. ''Revolution and Defeat: The Story of the Greek Communist Party,'' London, 1965 * Marantzidis, Nikos. "The Greek Civil War (1944вҖ“1949) and the International Communist System." ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' 15.4 (2013): 25вҖ“54. * Mazower. M. (ed.) ''After the War was Over. Reconstructing the Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943вҖ“1960'' Princeton University Press, 2000

* Nachmani, Amikam. "Civil War and Foreign Intervention in Greece: 1946вҖ“49" ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1990) 25#4 pp. 489вҖ“52

online

* Nachmani, Amikam. ''International intervention in the Greek Civil War'', 1990 () * Plakoudas, Spyridon. ''The Greek Civil War: Strategy, Counterinsurgency and the Monarchy'' (2017) * Sarafis, Marion (editor), ''Greece вҖ“ from resistance to civil war'', (Bertrand Russell House Leicester 1980) () * Sarafis, Marion, & Martin Eve (editors), ''Background to contemporary Greece'', (vols 1 & 2, Merlin Press London 1990) () * Sarafis, Stefanos. ''ELAS: Greek Resistance Army'', Merlin Press London 1980 (Greek original 1946 & 1964) * Sfikas, Thanasis D. ''The Greek Civil War: Essays on a Conflict of Exceptionalism and Silences'' (Routledge, 2017). * Stavrakis, Peter J. ''Moscow and Greek Communism, 1944вҖ“1949'' (Cornell University Press, 1989

excerpt

* Tsoutsoumpis, Spyros. "The Will to Fight: Combat, Morale, and the Experience of National Army Soldiers during the Greek Civil War, 1946вҖ“1949." ''International Journal of Military History and Historiography'' 1.aop (2022): 1-33. * Vlavianos. Haris. ''Greece, 1941вҖ“49: From Resistance to Civil War: The Strategy of the Greek Communist Party'' (1992)

in JSTOR

* Myers, E.C.F. ''Greek entanglement'' (Sutton Publishing, Limited, 1985) * Richter, Heinz. ''British Intervention in Greece. From Varkiza to Civil War'', London, 1985 () * Sfikas, Athanasios D. ''British Labour Government and The Greek Civil War: 1945вҖ“1949'' (Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

online

* Marantzidis, Nikos, and Giorgos Antoniou. "The axis occupation and civil war: Changing trends in Greek historiography, 1941вҖ“2002." ''Journal of Peace Research'' (2004) 41#2 pp: 223вҖ“231

online

* Nachmani, Amikam. "Civil War and Foreign Intervention in Greece: 1946вҖ“49." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1990): 489вҖ“522

in JSTOR

* Plakoudas, Spyridon. ''The Greek Civil War: Strategy, Counterinsurgency and the Monarchy'' (2017) pp 119вҖ“127. * Stergiou, Andreas. "Greece during the cold war." ''Southeast European and Black Sea Studies'' (2008) 8#1 pp: 67вҖ“73. * Van Boeschoten, Riki. "The trauma of war rape: A comparative view on the Bosnian conflict and the Greek civil war." ''History and Anthropology'' (2003) 14#1 pp: 41вҖ“44.

A full referenced history of DSE

Andartikos вҖ“ a short history of the Greek Resistance, 1941вҖ“5

on libcom.org/history

Dangerous Citizens Online

online version of Neni PanourgiГЎ's ''Dangerous Citizens: The Greek Left and the Terror of the State''

О‘ПҖОҝО»ОҝОіО№ПғОјПҢПӮ П„ПүОҪ 'О”ОөОәОөОјОІПҒО№ОұОҪПҺОҪ'

(only in Greek) О•ПҶО·ОјОөПҒОҜОҙОұ ОӨОҹ О’О—ОңО‘-О”ОөОәОӯОјОІПҒО·ПӮ 1944:60 ПҮПҒПҢОҪО№Оұ ОјОөП„О¬

Battle of Grammos-Vitsi

The decisive battle which ended the Greek Civil War {{authority control Greek Civil War, History of modern Greece Aftermath of World War II Anti-communism in Greece Communism-based civil wars Communism in Greece GreeceвҖ“United Kingdom relations Revolution-based civil wars Riots and civil disorder in Greece Wars involving Greece Wars involving Albania Wars involving Bulgaria Wars involving the United Kingdom Wars involving the United States Wars involving Yugoslavia 1940s in Greek politics 1946 in Greece 1947 in Greece 1948 in Greece 1949 in Greece Communist rebellions Proxy wars GreeceвҖ“Soviet Union relations

Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece ( grc, label= Greek, О’ОұПғОҜО»ОөО№ОҝОҪ П„бҝҶПӮ бјҷО»О»О¬ОҙОҝПӮ ) was established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople, wh ...

, which was supported by the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and won in the end. The losing opposition held a self-proclaimed people's republic

People's republic is an official title, usually used by some currently or formerly communist or left-wing states. It is mainly associated with soviet republics, socialist states following people's democracy, sovereign states with a democratic- ...

, the Provisional Democratic Government of Greece, which was governed by the Communist Party of Greece

The Communist Party of Greece ( el, ОҡОҝОјОјОҝП…ОҪО№ПғП„О№ОәПҢ ОҡПҢОјОјОұ О•О»О»О¬ОҙОұПӮ, ''KommounistikГі KГіmma EllГЎdas'', KKE) is a political party in Greece.

Founded in 1918 as the Socialist Labour Party of Greece and adopted its curre ...

(KKE) and its military branch, the Democratic Army of Greece

The Democratic Army of Greece (DAG; el, О”О·ОјОҝОәПҒОұП„О№ОәПҢПӮ ОЈП„ПҒОұП„ПҢПӮ О•О»О»О¬ОҙОұПӮ - О”ОЈО•, DimokratikГіs StratГіs EllГЎdas - DSE) was the army founded by the Communist Party of Greece during the Greek Civil War (1946вҖ“1949). At ...

(DSE). The rebels were supported by Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, РҲСғРіРҫСҒлавиСҳР° ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, РҲСғРіРҫСҒлавиСҳР° ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, JugoszlГЎvia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, ЮгРҫСҒлавиСҸ, translit=Juhoslavij ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

The war has its roots at the WW2 conflict, between the communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

-dominated left-wing resistance organisation, the EAM-ELAS

The Greek People's Liberation Army ( el, О•О»О»О·ОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ ОӣОұПҠОәПҢПӮ О‘ПҖОөО»ОөП…ОёОөПҒПүП„О№ОәПҢПӮ ОЈП„ПҒОұП„ПҢПӮ (О•ОӣО‘ОЈ), ''EllinikГіs LaГҜkГіs ApeleftherotikГіs StratГіs'' (ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberat ...

, and loosely-allied anticommunist resistance forces. It later escalated into a major civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

between the state and the communists. Fighting resulted in the defeat of the DSE by the Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army ( el, О•О»О»О·ОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ ОЈП„ПҒОұП„ПҢПӮ, EllinikГіs StratГіs, sometimes abbreviated as О•ОЈ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is th ...

.

The civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

resulted from a highly-polarised struggle between left and right ideologies that started in 1943. From 1944, each side targeted the power vacuum resulting from the end of Axis occupation (1941вҖ“1944) during World War II. The struggle was the first proxy war

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a p ...

of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

and represents the first example of postwar involvement on the part of the Allies in the internal affairs of a foreign country, an implementation of George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 вҖ“ March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

's containment policy

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term '' cordon sanitaire'', whic ...

in his Long Telegram

The "X Article" is an article, formally titled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct", written by George F. Kennan and published under the pseudonym "X" in the July 1947 issue of ''Foreign Affairs'' magazine. The article widely introduced the term " ...

. Greece in the end was funded by the United States (through the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It wa ...

and the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

) and joined NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traitГ© de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states вҖ“ 28 European and two N ...

(1952), while the insurgents were demoralized by the bitter split between the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; вҖ“ 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, who wanted to end the war, and Yugoslavia's Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, РҲРҫСҒРёРҝ Р‘СҖРҫР·, ; 7 May 1892 вҖ“ 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, РўРёСӮРҫ, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

, who wanted it to continue.

Robert Service summarizes Soviet vacillations:

The first signs of the civil war occurred in 1942 to 1944, during the Axis occupation of Greece. With the Greek government-in-exile

The Greek government-in-exile was formed in 1941, in the aftermath of the Battle of Greece and the subsequent occupation of Greece by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The government-in-exile was based in Cairo, Egypt, and hence it is also referr ...

unable to influence the situation at home, various resistance groups of differing political affiliations emerged, the dominant ones being the leftist National Liberation Front (EAM) and its military branch, the Greek People's Liberation Army

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

* Greeks, an ethnic group.

* Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

** Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ances ...

(ELAS), which was effectively controlled by the KKE. In autumn 1943, friction between the EAM and the other resistance groups started to result in scattered clashes, which continued until spring 1944, when an agreement was reached forming a national unity government that included six EAM-affiliated ministers.

The immediate prelude to the civil war took place in Athens on December 3, 1944, less than two months after the Germans had retreated from the area. After an order to disarm, leftists resigned from the government and called for resistance. A riot (the ''Dekemvriana

The ''Dekemvriana'' ( el, О”ОөОәОөОјОІПҒО№ОұОҪО¬, "December events") refers to a series of clashes fought during World War II in Athens from 3 December 1944 to 11 January 1945. The conflict was the culmination of months of tension between the c ...

'') erupted, and Greek government gendarmes opened fire on a pro-EAM rally, killed 28 demonstrators and injured dozens. The rally had been organised under the pretext of demonstrating against the perceived impunity of the collaborators and the general disarmament ultimatum, signed by Ronald Scobie

Lieutenant-General Sir Ronald MacKenzie Scobie, (8 June 1893 вҖ“ 23 February 1969) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars, where he commanded the 70th Infantry Division and later III Corps. He was ...

, the British commander in Greece. The battle lasted 33 days and resulted in the defeat of the EAM. The subsequent signing of the Treaty of Varkiza (12 February 1945) spelled the end of the left-wing organization's ascendancy. The ELAS was partly disarmed, and the EAM soon after lost its multi-party character to become dominated by the KKE.

The war erupted in 1946, when former ELAS partisans, who had found shelter in their hideouts and were controlled by the KKE, organised the DSE and its High Command headquarters. The KKE supported the endeavour and decided that there was no other way to act against the internationally-recognised government formed after the 1946 elections, which the KKE had boycotted. The communists formed a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

in December 1947 and made the DSE the military branch of this government. The neighboring communist states of Albania

Albania ( ; sq, ShqipГ«ri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e ShqipГ«risГ«), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, Р‘СҠлгаСҖРёСҸ, BЗҺlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

offered logistical support to this provisional government, especially to the forces operating in northern Greece.

Despite some setbacks that the government forces suffered from 1946 to 1948, they eventually won largely because of increased American aid, the failure of the DSE to attract sufficient recruits, and the side effects of the TitoвҖ“Stalin split

The TitoвҖ“Stalin split or the YugoslavвҖ“Soviet split was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, respectively, in the years following World W ...

of 1948. The final victory of the western-allied government forces led to Greece's membership in NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traitГ© de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states вҖ“ 28 European and two N ...

on 1952 and helped to define the ideological balance of power in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: О‘О№ОіОұОҜОҝ О ОӯО»ОұОіОҝПӮ: "EgГ©o PГ©lagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

for the entire Cold War. The civil war also left Greece with a strongly anticommunist security arrangement, one of the factors which led to the establishment of the Greek military junta of 1967вҖ“1974

The Greek junta or Regime of the Colonels, . Also known within Greece as just the Junta ( el, О· О§ОҝПҚОҪП„Оұ, i ChoГәnta, links=no, ), the Dictatorship ( el, О· О”О№ОәП„ОұП„ОҝПҒОҜОұ, i DiktatorГӯa, links=no, ) or the Seven Years ( el, О· О• ...

.

Background: 1941вҖ“1944

Origins

While Axis forces approachedAthens

Athens ( ; el, О‘ОёО®ОҪОұ, AthГӯna ; grc, бјҲОёбҝҶОҪОұО№, AthГӘnai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

in April 1941, King George II and his government escaped to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, Щ…ШөШұ , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, where they proclaimed a government-in-exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile ...

, recognised by the UK but not by the Soviet Union. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

encouraged King George II of Greece

George II ( el, О“ОөПҺПҒОіО№ОҝПӮ О’К№, ''GeГіrgios II''; 19 July Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S.:_7_July.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S.:_7_July">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;"title="nowiki/ ...

to appoint a moderate cabinet. As a result, only two of his ministers were previous members of the 4th of August Regime

The 4th of August Regime ( el, ОҡОұОёОөПғП„ПҺПӮ П„О·ПӮ 4О·ПӮ О‘П…ОіОҝПҚПғП„ОҝП…, KathestГіs tis tetГЎrtis AvgoГәstou), commonly also known as the Metaxas regime (, ''KathestГіs MetaxГЎ''), was a totalitarian regime under the leadership of Gener ...

under Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, ОҷПүО¬ОҪОҪО·ПӮ ОңОөП„ОұОҫО¬ПӮ; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

, who had both seized power in a ''coup d'Г©tat'' with the blessing of the king and governed the country since August 1936. Nevertheless, the exiled government's inability to influence affairs inside Greece rendered it irrelevant in the minds of most Greek people. At the same time, the Germans set up a collaborationist government in Athens, which lacked legitimacy and support. The puppet regime

A puppet state, puppet rГ©gime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

was further undermined when economic mismanagement in wartime conditions created runaway inflation, acute food shortages and famine among the civilian population.

The power vacuum that the occupation created was filled by several resistance movements that ranged from royalist to communist ideologies. Resistance was born first in eastern Macedonia and Thrace, where Bulgarian troops occupied Greek territory. Soon large demonstrations were organized in many cities by the Defenders of Northern Greece

Defender(s) or The Defender(s) may refer to:

*Defense (military)

*Defense (sports)

**Defender (association football)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Defender'' (1989 film), a Canadian documentary

* ''The Defender'' (1994 f ...

(YVE), a patriotic organization. However, the largest group to emerge was the National Liberation Front (EAM), founded on 27 September 1941 by representatives of four left-wing parties. Proclaiming that it followed the Soviet policy of creating a broad united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

against fascism, EAM won the support of many non-communist patriots.

These resistance groups launched attacks against the occupying powers and set up large espionage networks. The communist leaders of EAM, however, had planned to dominate in postwar Greece, so, usually by force, they tried to take over or destroy the other Greek resistance groups (such as the destruction of National and Social Liberation

National and Social Liberation (, ''EthnikГӯ kai KoinonikГӯ ApelefthГ©rosis'' (EKKA)) was a Greek Resistance movement during the Axis occupation of Greece. It was founded in autumn 1942 by Colonel Dimitrios Psarros and politician Georgios Ka ...

(EKKA) and the murder of its leader, Dimitrios Psarros

Dimitrios Psarros (; 1893 вҖ“ April 17, 1944) was a Greek army officer, founder and leader of the resistance group National and Social Liberation (EKKA), the third-most significant organization of the Greek Resistance movement after the Natio ...

by ELAS partisans) and undertaking a campaign of Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: РҡСҖР°СҒРҪСӢР№ СӮРөСҖСҖРҫСҖ, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in ...

. When liberation came in October 1944, Greece was in a state of crisis, which soon led to the outbreak of civil war.

Although controlled by the KKE, the organization had democratic republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

rhetoric. Its military wing, the Greek People's Liberation Army

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

* Greeks, an ethnic group.

* Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

** Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ances ...

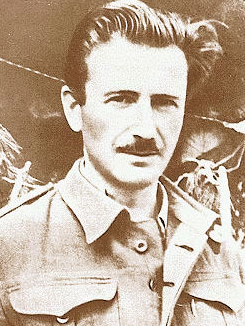

(ELAS) was founded in February 1942. Aris Velouchiotis

Athanasios Klaras ( el, О‘ОёОұОҪО¬ПғО№ОҝПӮ ОҡО»О¬ПҒОұПӮ; August 27, 1905 вҖ“ June 15, 1945), better known by the ''nom de guerre'' Aris Velouchiotis ( el, ОҶПҒО·ПӮ О’ОөО»ОҝП…ПҮО№ПҺП„О·ПӮ), was a Greek journalist, politician, member of the Commun ...

, a member of KKE's Central Committee, was nominated Chief (''Kapetanios'') of the ELAS High Command. The military chief, Stefanos Sarafis

Stefanos Sarafis ( el, ОЈП„ОӯПҶОұОҪОҝПӮ ОЈОұПҒО¬ПҶО·ПӮ, 23 October 1890 вҖ“ 31 May 1957) was an officer of the Hellenic Army and Major General in EAM-ELAS), who played an important role during the Greek Resistance.

Early life and career

Sara ...

, was a colonel in the prewar Greek army who had been dismissed during the Metaxas regime for his views. The political chief of EAM was Vasilis Samariniotis (''nom de guerre'' of Andreas Tzimas

Andreas Tzimas ( el, О‘ОҪОҙПҒОӯОұПӮ ОӨО¶О®ОјОұПӮ; Kastoria, 1 September 1909 вҖ“ Prague, 1 December 1972), known also under his World War II-era '' nom de guerre'' of Vasilis Samariniotis (О’ОұПғОҜО»О·ПӮ ОЈОұОјОұПҒО№ОҪО№ПҺП„О·ПӮ), was a leading ...

).

The Organization for the Protection of the People's Struggle

The Organization for the Protection of the People's Struggle ( el, ОҹПҒОіО¬ОҪПүПғО· О ОөПҒО№ПҶПҒОҝПҚПҒО·ПғО·ПӮ ОӣОұПҠОәОҝПҚ О‘ОіПҺОҪОұ, abbreviated ОҹО ОӣО‘ – OPLA, an acronym meaning "weapons" in Greek) was a special division of the Communis ...

(OPLA) was founded as EAM's security militia, operating mainly in the occupied cities and most particularly Athens. A small Greek People's Liberation Navy

The Greek People's Liberation Navy (; ''Elliniko Laiko Apeleftherotiko Naftiko''), commonly abbreviated as ELAN (О•ОӣО‘Оқ), was the naval force of the communist-led Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) resistance movement during World War II, ...

(ELAN) was created, operating mostly around the Ionian Islands and some other coastal areas. Other Communist-aligned organizations were present, including the National Liberation Front (NOF), composed mostly of Slavic Macedonians

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Slavi ...

in the Florina

Florina ( el, ОҰО»ПҺПҒО№ОҪОұ, ''FlГіrina''; known also by some alternative names) is a town and municipality in the mountainous northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the capital of the F ...

region. They would later play a critical role in the civil war. The two other large resistance movements were the National Republican Greek League

The National Republican Greek League ( el, О•ОёОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ О”О·ОјОҝОәПҒОұП„О№ОәПҢПӮ О•О»О»О·ОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ ОЈПҚОҪОҙОөПғОјОҝПӮ (О•О”О•ОЈ), ''EthnikГіs DimokratikГіs EllinikГіs SГҪndesmos'' (EDES)) was one of the major resistance groups formed during t ...

(EDES), led by republican former army officer Colonel Napoleon Zervas

Napoleon Zervas ( el, ОқОұПҖОҝО»ОӯПүОҪ О–ОӯПҒОІОұПӮ; May 17, 1891 вҖ“ December 10, 1957) was a Hellenic Army officer and resistance leader during World War II. He organized and led the National Republican Greek League (EDES), the second most signi ...

, and the social-liberal EKKA, led by Colonel Dimitrios Psarros

Dimitrios Psarros (; 1893 вҖ“ April 17, 1944) was a Greek army officer, founder and leader of the resistance group National and Social Liberation (EKKA), the third-most significant organization of the Greek Resistance movement after the Natio ...

.

Guerrilla control over rural areas

The Greek landscape was favourable to guerrilla operations, and by 1943, the Axis forces and their collaborators were in control only of the main towns and connecting roads, leaving the mountainous countryside to the resistance. EAM-ELAS in particular controlled most of the country's mountainous interior, while EDES was limited toEpirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

and EKKA to eastern Central Greece

Continental Greece ( el, ОЈП„ОөПҒОөО¬ О•О»О»О¬ОҙОұ, StereГЎ EllГЎda; formerly , ''ChГ©rsos EllГЎs''), colloquially known as RoГәmeli (ОЎОҝПҚОјОөО»О·), is a traditional geographic region of Greece. In English, the area is usually called Central ...

. By early 1944 ELAS could call on nearly 25,000 men under arms, with another 80,000 working as reserves or logistical support, EDES had roughly 10,000 men, and EKKA had under 10,000 men.

To combat the rising influence of the EAM, and fearful of an eventual takeover after the German defeat, in 1943, Ioannis Rallis

Ioannis Rallis ( el, ОҷПүО¬ОҪОҪО·ПӮ О”. ОЎО¬О»О»О·ПӮ; 1878 вҖ“ 26 October 1946) was the third and last collaborationist prime minister of Greece during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, holding office from 7 April 1943 to 12 Oct ...

, the Prime Minister of the collaborationist government, authorised the creation of paramilitary forces, known as the Security Battalions

The Security Battalions ( el, ОӨО¬ОіОјОұП„Оұ О‘ПғПҶОұО»ОөОҜОұПӮ, Tagmata Asfaleias, derisively known as ''Germanotsoliades'' (О“ОөПҒОјОұОҪОҝП„ПғОҝО»О№О¬ОҙОөПӮ) or ''Tagmatasfalites'' (ОӨОұОіОјОұП„ОұПғПҶОұО»ОҜП„ОөПӮ)) were Greek collaborationist m ...

. Numbering 20,000 at their peak in 1944, composed mostly of local fascists, convicts, sympathetic prisoners-of-war and forcibly impressed conscripts, they operated under German command in Nazi security warfare

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

operations and soon achieved a reputation for brutality.

EAM-ELAS, EDES and EKKA were mutually suspicious and tensions were exacerbated as the end of the war became nearer and the question of the country's political future arose. The role of the British military mission in these events proved decisive. EAM was by far the largest and most active group but was determined to achieve its own political goal to dominate postwar Greece, and its actions were not always directed against the Axis powers. Consequently, British material support was directed mostly to the more reliable Zervas, who by 1943 had reversed his earlier anti-monarchist stance.

First conflicts: 1943вҖ“1944

The Western allies, at first, provided all resistance organisations with funds and equipment. However, they gave special preference to ELAS, which they saw as the most reliable partner and a formidable fighting force that would be able to create more problems for the Axis than other resistance movements. As the end of the war approached, the BritishForeign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

, fearing a possible Communist upsurge, observed with displeasure the transformation of ELAS into a large-scale conventional army more and more out of Allied control. After the September 8, 1943, Armistice with Italy

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Briga ...

, ELAS seized control of Italian garrison weapons in the country. In response, the Western allies began to favor rival anti-Communist resistance groups. They provided them with ammunition, supplies and logistical support as a way of balancing ELAS's increasing influence. In time, the flow of weapons and funds to ELAS stopped altogether, and rival EDES received the bulk of the Allied support.

In mid-1943 the animosity between ELAS and the other movements erupted into armed conflict. The communists and EAM accused EDES of being traitors and collaborators, and vice versa. Other smaller groups, such as EKKA, continued the anti-occupation fight with sabotage and other actions. They declined to join the ranks of ELAS. While some organizations accepted assistance from the Nazis in their operations against ELAS, the great majority of the population refused any form of cooperation with the occupation authorities. By early 1944, after a British-negotiated ceasefire (the Plaka Agreement), ELAS had destroyed EKKA and confined EDES to a small part of

In mid-1943 the animosity between ELAS and the other movements erupted into armed conflict. The communists and EAM accused EDES of being traitors and collaborators, and vice versa. Other smaller groups, such as EKKA, continued the anti-occupation fight with sabotage and other actions. They declined to join the ranks of ELAS. While some organizations accepted assistance from the Nazis in their operations against ELAS, the great majority of the population refused any form of cooperation with the occupation authorities. By early 1944, after a British-negotiated ceasefire (the Plaka Agreement), ELAS had destroyed EKKA and confined EDES to a small part of Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, where it could only play a marginal role in the rest of the war. Its political network (EAM) had reached about 500,000 citizens around the country. By 1944, ELAS had the numerical advantage in armed fighters, having more than 50,000 men in arms and an extra 500,000 working as reserves or logistical support personnel (''Efedrikos ELAS''). In contrast, EDES and EKKA had around 10,000 fighters each

After the declaration of the formation of the Security Battalions, KKE and EAM implemented a pre-emptive policy of terror, mainly in the Peloponnese countryside areas close to garrisoned German units, to ensure civilian allegiance. As the communist position strengthened, so did the numbers of the "Security Battalions", with both sides engaged in skirmishes. The ELAS units were accused of what became known as the Meligalas

Meligalas ( el, ОңОөО»О№ОіОұО»О¬ПӮ) is a town and former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Oichalia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an are ...

massacre. Meligalas was the headquarters of a local Security Battalion Unit that was given control of the wider area of Messenia by the Nazis. After a battle there between ELAS and the Security Battalions, ELAS forces prevailed, and the remaining forces of the collaborators were taken into custody.

After the civil war ended, postwar governments declared that 1000 members of the collaborationist units were massacred along with civilians by the Communists; however, that number was not matched by the actual numbers of bodies found in the mass grave (an old well in the area) of executed Security Battalion and civilian prisoners. According to left-wing sources, civilian bodies found there could have been victims of the Security Battalions. As Security Battalions were replacing occupation forces in territories the Germans could not enter, they were accused of many instances of brutality against civilians and captured partisans, and of the executions of prominent EAM and KKE members by hanging.

In addition, recruiting by both sides was controversial, as the case of Stefanos Sarafis

Stefanos Sarafis ( el, ОЈП„ОӯПҶОұОҪОҝПӮ ОЈОұПҒО¬ПҶО·ПӮ, 23 October 1890 вҖ“ 31 May 1957) was an officer of the Hellenic Army and Major General in EAM-ELAS), who played an important role during the Greek Resistance.

Early life and career

Sara ...

indicates. The soon-to-be military leader of ELAS sought to join the noncommunist resistance group commanded by Kostopoulos in Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, ОҳОөПғПғОұО»ОҜОұ, translit=ThessalГӯa, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, along with other former officers. On their way, they were captured by an ELAS group, with Sarafis agreeing to join ELAS at gunpoint when all other officers who refused were killed., noted at Sarafis never admitted this incident, and in his book on ELAS makes special reference to the letter that he sent all officers of the former Greek army to join the ranks of EAM-ELAS. Again, numbers favored the EAM organisation; nearly 800 officers of the pre-war Greek army joined the ranks of ELAS with the position of military leader and Kapetanios.

Egypt "mutiny" and the Lebanon Conference

In March 1944, EAM established the Political Committee of National Liberation (''Politiki Epitropi Ethnikis Apeleftherosis'', or PEEA), in effect a third Greek government to rival those in Athens and Cairo "to intensify the struggle against the conquerors... for full national liberation, for the consolidation of the independence and integrity of our country... and for the annihilation of domestic Fascism and armed traitor formations." PEEA was dominated by, but not composed exclusively of Communists.

The moderate aims of the PEEA (known as "ОәП…ОІОӯПҒОҪО·ПғО· П„ОҝП… ОІОҝП…ОҪОҝПҚ", "the Mountain Government") aroused support even among Greeks in exile. In April 1944 the Egypt based

In March 1944, EAM established the Political Committee of National Liberation (''Politiki Epitropi Ethnikis Apeleftherosis'', or PEEA), in effect a third Greek government to rival those in Athens and Cairo "to intensify the struggle against the conquerors... for full national liberation, for the consolidation of the independence and integrity of our country... and for the annihilation of domestic Fascism and armed traitor formations." PEEA was dominated by, but not composed exclusively of Communists.

The moderate aims of the PEEA (known as "ОәП…ОІОӯПҒОҪО·ПғО· П„ОҝП… ОІОҝП…ОҪОҝПҚ", "the Mountain Government") aroused support even among Greeks in exile. In April 1944 the Egypt based Free Greek Forces After the fall of Greece to the Axis powers in AprilвҖ“May 1941, elements of the Greek Armed Forces managed to escape to the British-controlled Middle East. There they were placed under the Greek government in exile, and continued the fight alongs ...

, many of them well-disposed towards EAM, demanded for a government of national unity to be established, based on PEEA principles, to replace the government-in-exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile ...

, as it had no political or other link with the occupied home country and that any pro-fascist elements in the Army be removed.

The movement threatened Allied unity, angering Great Britain and the United States. British and Greek troops loyal to the exiled government moved to suppress the PEEA. Approximately 5,000 Greek soldiers and officers were disarmed and deported to prison camps. After the mutiny, allied economic aid to the National Liberation Front almost stopped. Later on, through political screening of the officers, the Cairo government created the III Greek Mountain Brigade, composed of staunchly anti-communist personnel, under the command of Brigadier Thrasyvoulos Tsakalotos

Thrasyvoulos Tsakalotos ( el, ОҳПҒОұПғПҚОІОҝП…О»ОҝПӮ ОӨПғОұОәОұО»ПҺП„ОҝПӮ; 3 April 1897 – 15 August 1989) was a distinguished Hellenic Army Lieutenant General who served in World War I, the Greco-Turkish War of 1919вҖ“1922, World War II and ...

.

In May 1944, representatives from all political parties and resistance groups came together at the Lebanon Conference under the leadership of Georgios Papandreou, in hopes of forming a government of national unity. Despite EAM's accusations of collaboration made against all other Greek resistance forces and charges against EAM-ELAS members of murders, banditry and thievery, the conference ended with an agreement (the National Contract) for a government of national unity consisting of 24 ministers (6 to be EAM members). The agreement was made possible by Soviet directives to KKE to avoid harming Allied unity, but did not resolve the problem of disarmament of resistance groups.

Confrontation: 1944

By 1944,EDES

The National Republican Greek League ( el, О•ОёОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ О”О·ОјОҝОәПҒОұП„О№ОәПҢПӮ О•О»О»О·ОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ ОЈПҚОҪОҙОөПғОјОҝПӮ (О•О”О•ОЈ), ''EthnikГіs DimokratikГіs EllinikГіs SГҪndesmos'' (EDES)) was one of the major resistance groups formed during t ...

and ELAS

The Greek People's Liberation Army ( el, О•О»О»О·ОҪО№ОәПҢПӮ ОӣОұПҠОәПҢПӮ О‘ПҖОөО»ОөП…ОёОөПҒПүП„О№ОәПҢПӮ ОЈП„ПҒОұП„ПҢПӮ (О•ОӣО‘ОЈ), ''EllinikГіs LaГҜkГіs ApeleftherotikГіs StratГіs'' (ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberat ...

each saw the other to be their great enemy. They both saw that the Germans were going to be defeated and were a temporary threat. For the ELAS, the British represented their major problem, even while for the majority of Greeks, the British were their major hope for an end to the war.

From the Lebanon Conference to the outbreak

By the summer of 1944, it was obvious that the Germans would soon withdraw from Greece, as Soviet forces were advancing into Romania and towards Yugoslavia, threatening to cut off the retreating Germans. In September, GeneralFyodor Tolbukhin

Fyodor Ivanovich Tolbukhin (russian: РӨС‘РҙРҫСҖ РҳРІР°МҒРҪРҫРІРёСҮ РўРҫР»РұСғМҒС…РёРҪ; 16 June 1894 – 17 October 1949) was a Soviet military commander and Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Early life and military career

Tolbukhin was born into ...

's armies advanced into Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, Р‘СҠлгаСҖРёСҸ, BЗҺlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, forcing the resignation of the country's pro-Nazi government and the establishment of a pro-communist regime, while Bulgarian troops withdrew from Greek Macedonia

Macedonia (; el, ОңОұОәОөОҙОҝОҪОҜОұ, MakedonГӯa ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and Greek geographic region, with a population of 2.36 million in 2020. It is ...

. The government-in-exile, now led by prominent liberal George Papandreou

George Andreas Papandreou ( el, О“ОөПҺПҒОіО№ОҝПӮ О‘ОҪОҙПҒОӯОұПӮ О ОұПҖОұОҪОҙПҒОӯОҝП…, , shortened to ''Giorgos'' () to distinguish him from his grandfather; born 16 June 1952) is a Greek politician who served as Prime Minister of Greece from ...

, moved to Italy, in preparation for its return to Greece. Under the Caserta Agreement of September 1944, all resistance forces in Greece were placed under the command of a British officer, General Ronald Scobie

Lieutenant-General Sir Ronald MacKenzie Scobie, (8 June 1893 вҖ“ 23 February 1969) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars, where he commanded the 70th Infantry Division and later III Corps. He was ...

. The Western Allies arrived in Greece in October, by which time the Germans were in full retreat and most of Greece's territory had already been liberated by Greek partisans. On October 13, British troops entered Athens, the only area still occupied by the Germans, and Papandreou and his ministers followed six days later. The king stayed in Cairo because Papandreou had promised that the future of the monarchy would be decided by referendum.

There was little to prevent the ELAS from taking full control of the country. With the German withdrawal, ELAS units had taken control of the countryside and most cities. However, they did not take full control because the KKE leadership was instructed by the Soviet Union not to precipitate a crisis that could jeopardize Allied unity and put Stalin's larger postwar objectives at risk. The KKE's leadership knew so, but the ELAS's fighters and rank-and-file Communists did not, which became a source of conflict within both EAM and ELAS. Following Stalin's instructions, the KKE's leadership tried to avoid a confrontation with the Papandreou government. The majority of the ELAS members saw the Western Allies as liberators, although some KKE leaders, such as Andreas Tzimas

Andreas Tzimas ( el, О‘ОҪОҙПҒОӯОұПӮ ОӨО¶О®ОјОұПӮ; Kastoria, 1 September 1909 вҖ“ Prague, 1 December 1972), known also under his World War II-era '' nom de guerre'' of Vasilis Samariniotis (О’ОұПғОҜО»О·ПӮ ОЈОұОјОұПҒО№ОҪО№ПҺП„О·ПӮ), was a leading ...

and Aris Velouchiotis

Athanasios Klaras ( el, О‘ОёОұОҪО¬ПғО№ОҝПӮ ОҡО»О¬ПҒОұПӮ; August 27, 1905 вҖ“ June 15, 1945), better known by the ''nom de guerre'' Aris Velouchiotis ( el, ОҶПҒО·ПӮ О’ОөО»ОҝП…ПҮО№ПҺП„О·ПӮ), was a Greek journalist, politician, member of the Commun ...

, did not trust them. Tzimas was in touch with Yugoslav communist leader Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, РҲРҫСҒРёРҝ Р‘СҖРҫР·, ; 7 May 1892 вҖ“ 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, РўРёСӮРҫ, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

and disagreed with ELAS's cooperation with the Western Allied forces.

The issue of disarming the resistance organizations was a cause of friction between the Papandreou government and its EAM members. Advised by British ambassador Reginald Leeper

Sir Reginald "Rex" Wilding Allen Leeper (25 March 1888 вҖ“ 2 February 1968) was a British civil servant and diplomat. He was the founder of the British Council.

Born in Sydney, Australia, Leeper was educated at Melbourne Grammar School, Melb ...

, Papandreou demanded the disarmament of all armed forces apart from the Sacred Band and the III Mountain Brigade, which had been formed following the suppression of the April 1944 Egypt mutiny, and the constitution of a National Guard under government control. The communists, believing that it would leave the ELAS defenseless against its opponents, submitted an alternative plan of total and simultaneous disarmament, but Papandreou rejected it, causing EAM ministers to resign from the government on December 2. On December 1, Scobie issued a proclamation calling for the dissolution of ELAS. Command of ELAS was KKE's greatest source of strength, and KKE leader Siantos decided that the demand for ELAS's dissolution must be resisted.

Tito's influence may have played some role in ELAS's resistance to disarmament. Tito was outwardly loyal to Stalin, but had come to power through his own means and believed that communist Greeks should do the same. His influence, however, had not prevented the EAM leadership from putting its forces under Scobie's command a couple of months earlier in accordance with the Caserta Agreement. In the meantime, following Georgios Grivas

Georgios Grivas ( el, О“ОөПҺПҒОіО№ОҝПӮ О“ПҒОҜОІОұПӮ; 6 June 1897 вҖ“ 27 January 1974), also known by his nickname Digenis ( el, О”О№ОіОөОҪО®ПӮ), was a Cypriot general in the Hellenic Army and the leader of the Organization X (1942-1949), EOKA ...

's instructions, Organization X

The Organization ''X'' ( el, ОҹПҒОіО¬ОҪПүПғО№ПӮ О§; commonly referred to simply as ''X'' ("Chi" in Greek), and members as Chites (О§ОҜП„ОөПӮ)) was a paramilitary right-wing anti-communist royalist organization set up in 1941 during the Axis oc ...

members had set up outposts in central Athens and resisted EAM for several days, until British troops arrived, as their leader had been promised.

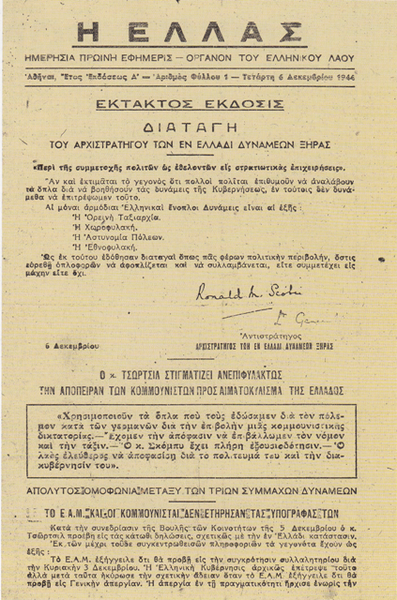

The ''Dekemvriana'' events

According to the Caserta Agreement all Greek forces (tactical and guerillas) were under Allied command. On December 1, 1944, the Greek government of "National Unity" under Papandreou and Scobie (the British head of the Allied forces in Greece) announced an ultimatum for the general disarmament of all guerrilla forces by 10 December excluding the tactical forces (the 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade and the Sacred Squadron); and also a part of EDES and ELAS that would be used, if it was necessary, in Allied operations inCrete

Crete ( el, ОҡПҒО®П„О·, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, О”ПүОҙОөОәО¬ОҪО·ПғОұ, ''DodekГЎnisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited ...

against the remaining German army. As a result, on December 2 six ministers of the EAM, most of whom were KKE members, resigned from their positions in the "National Unity" government. The EAM called for a general strike and announced the reorganization of the Central Committee of ELAS, its military wing. A demonstration, forbidden by the government, was organised by EAM on December 3.

The demonstration involved at least 200,000 people marching in

The demonstration involved at least 200,000 people marching in Athens

Athens ( ; el, О‘ОёО®ОҪОұ, AthГӯna ; grc, бјҲОёбҝҶОҪОұО№, AthГӘnai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

on Panepistimiou Street

Panepistimiou Street ( el, ОҹОҙПҢПӮ О ОұОҪОөПҖО№ПғП„О·ОјОҜОҝП…, "University Street", named after the University of Athens, the central building of which is on the upper corner) is a major street in Athens that has run one way for non-transit v ...

towards the Syntagma Square

Syntagma Square ( el, О О»ОұП„ОөОҜОұ ОЈП…ОҪП„О¬ОіОјОұП„ОҝПӮ, , "Constitution Square") is the central square of Athens. The square is named after the Constitution that Otto, the first King of Greece, was obliged to grant after a popular and milit ...

. British tanks along with police units had been scattered around the area, blocking the way of the demonstrators. The shootings began when the marchers had arrived at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, above the Syntagma Square. They originated from the building of the General Police Headquarters, from the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

(О’ОҝП…О»О®), from the Hotel Grande Bretagne (where international observers had settled), from other governmental buildings and from policemen on the street.

Among many testimonies, N. Farmakis, a member of the Organization X

The Organization ''X'' ( el, ОҹПҒОіО¬ОҪПүПғО№ПӮ О§; commonly referred to simply as ''X'' ("Chi" in Greek), and members as Chites (О§ОҜП„ОөПӮ)) was a paramilitary right-wing anti-communist royalist organization set up in 1941 during the Axis oc ...

participating in the shootings, described that he heard the head of the police Angelos Evert

Angelos Evert ( el, ОҶОіОіОөО»ОҝПӮ ОҲОІОөПҒП„; german: Ewert; 10 April 1894 вҖ“ 30 December 1970) was a Greek police officer, most notable for serving as head of the Athens branch of the Cities Police during the Axis Occupation of Greece during ...

giving the order to open fire on the crowd. Although there are no accounts hinting that the crowd indeed possessed guns, the British commander Christopher Montague Woodhouse

Christopher Montague Woodhouse, 5th Baron Terrington, (11 May 1917 вҖ“ 13 February 2001) was a British Conservative politician who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Oxford from 1959 to 1966 and again from 1970 to 1974. He was also a visitin ...

insisted that it was uncertain whether the first shots were fired by the police or the demonstrators. A total of 28 protesters were killed by the Greek police that day, and hundreds were injured. This signaled the beginning of the ''Dekemvriana'' ( el, О”ОөОәОөОјОІПҒО№ОұОҪО¬, "the December events"), a 37-day period of full-scale fighting in Athens between EAM fighters and smaller parts of ELAS and the forces of the British army and the government.

At the beginning the government had only a few policemen and gendarmes, some militia units, the

At the beginning the government had only a few policemen and gendarmes, some militia units, the 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade

The 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade ( el, 3О· О•О»О»О·ОҪО№ОәО® ОҹПҒОөО№ОҪО® ОӨОұОҫО№ОұПҒПҮОҜОұ, ''Triti Elliniki Оҹrini ОӨaxiarkhia'', ОҷОҷОҷ О•.Оҹ.ОӨ.) was a unit of mountain infantry formed by the Greek government in exile in Egypt during World War I ...

, distinguished at the Gothic Line offensive in Italy, which, however, lacked heavy weapons, and the royalist group Organization X, also known as "Chites", which was accused by EAM of collaborating with the Nazis. Consequently, the British intervened in support of the government, freely using artillery and aircraft as the battle approached its last stages.