Government Of Macedonia (ancient Kingdom) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The earliest government of Macedonia was established by the Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings some time during the period of

The earliest government of Macedonia was established by the Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings some time during the period of

The earliest known government in ancient Macedonia was their monarchy, which lasted until 167 BC when it was abolished by the Romans.. Written evidence about Macedonian governmental institutions made before

The earliest known government in ancient Macedonia was their monarchy, which lasted until 167 BC when it was abolished by the Romans.. Written evidence about Macedonian governmental institutions made before

At the head of Macedonia's government was the king (''

At the head of Macedonia's government was the king (''

The Macedonian hereditary monarchy existed since at least the time of

The Macedonian hereditary monarchy existed since at least the time of

However, N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank state that the royal pages are attested to as far back as the reign of

The companions, including the elite

The companions, including the elite

During the reign of Alexander the Great, the only Macedonian cavalry units attested in battle were the companion cavalry. However, during his campaign in Asia against the Persian Empire he formed a '' hipparchia'' (i.e. unit of a few hundred horsemen) of companion cavalry composed entirely of ethnic

During the reign of Alexander the Great, the only Macedonian cavalry units attested in battle were the companion cavalry. However, during his campaign in Asia against the Persian Empire he formed a '' hipparchia'' (i.e. unit of a few hundred horsemen) of companion cavalry composed entirely of ethnic

Thanks to contemporary inscriptions from

Thanks to contemporary inscriptions from

The minting of silver coinage began during the reign of

The minting of silver coinage began during the reign of

Ancient Macedonia

a

Livius

by Jona Lendering * (''Philip, Demosthenes and the Fall of the Polis''). Yale University courses

Lecture 24

''Introduction to Ancient Greek History''

{{Ancient Syria and Mesopotamia Ancient Macedonia Hellenistic Macedonia

The earliest government of Macedonia was established by the Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings some time during the period of

The earliest government of Macedonia was established by the Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings some time during the period of Archaic Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from circa 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the M ...

(8th–5th centuries BC). Due to shortcomings in the historical record, very little is known about the origins of Macedonian governmental institutions before the reign of Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

(r. 359–336 BC), during the final phase of Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Marti ...

(480–336 BC). These institutions continued to evolve under his successor Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and the subsequent Antipatrid and Antigonid

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

dynasties of Hellenistic Greece

Hellenistic Greece is the historical period of the country following Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the annexation of the classical Greek Achaean League heartlands by the Roman Republic. This culminated ...

(336–146 BC). Following the Roman victory in the Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) was a war fought between the Roman Republic and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC, King Philip V of Macedon died and was succeeded by his ambitious son Perseus. He was anti-Roman and stirred anti-Roman ...

and house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if al ...

of Perseus of Macedon

Perseus ( grc-gre, Περσεύς; 212 – 166 BC) was the last king (''Basileus'') of the Antigonid dynasty, who ruled the successor state in Macedon created upon the death of Alexander the Great. He was the last Antigonid to rule Macedon, aft ...

in 168 BC, the Macedonian monarchy was abolished and replaced by four client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

republics.; ; ; see also for further details. However, the monarchy was briefly revived by the pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term is often used to suggest that a claim is not legitimate.Curley Jr., Walter J. P. ''Monarchs-in-Waiting'' ...

to the throne Andriscus

Andriscus ( grc, Ἀνδρίσκος, ''Andrískos''; 154/153 BC – 146 BC), also often referenced as Pseudo-Philip, was a Greek pretender who became the last independent king of Macedon in 149 BC as Philip VI ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος, ''Phil ...

in 150–148 BC, followed by the Roman victory in the Fourth Macedonian War

The Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by the pretender Andriscus, and the Roman Republic. It was the last of the Macedonian Wars, and was the last war to seriously threaten Roman control of Greece until the ...

and establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia

Macedonia ( grc-gre, Μακεδονία) was a province of the Roman Empire, encompassing the territory of the former Antigonid Kingdom of Macedonia, which had been conquered by Rome in 168 BC at the conclusion of the Third Macedonian War. The ...

.

It is unclear if there was a formally established constitution dictating the laws, organization, and divisions of power in ancient Macedonia's government, although some tangential evidence suggests this. The king (''basileus

''Basileus'' ( el, ) is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs in history. In the English-speaking world it is perhaps most widely understood to mean " monarch", referring to either a " king" or an "emperor" and ...

'') served as the head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

and was assisted by his noble companions and royal pages. Kings served as the chief judges of the kingdom, although little is known about Macedonia's judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

. The kings were also expected to serve as high priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious caste.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many gods rev ...

s of the nation, using their wealth to sponsor various religious cults. The Macedonian kings had command over certain natural resources such as gold from mining and timber from logging. The right to mint gold, silver, and bronze coins was shared by the central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loc ...

s.

The Macedonian kings served as the commanders-in-chief of Macedonia's armed forces, while it was common for them to personally lead troops into battle. Surviving textual evidence suggests that the ancient Macedonian army

The army of the Kingdom of Macedon was among the greatest military forces of the ancient world. It was created and made formidable by King Philip II of Macedon; previously the army of Macedon had been of little account in the politics of the Gr ...

exercised its authority in matters such as the royal succession when there was no clear heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to rule the kingdom. The army upheld some of the functions of a popular assembly

A popular assembly (or people's assembly) is a gathering called to address issues of importance to participants. Assemblies tend to be freely open to participation and operate by direct democracy. Some assemblies are of people from a location ...

, a democratic institution which otherwise existed in only a handful of municipal governments within the Macedonian commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

: the Koinon of Macedonians

The League of the Macedonians ( el, Κοινὸν τῶν Μακεδόνων, ''Koinòn tōn Makedónōn'') was a confederationally-organized commonwealth institution (i.e., an ancient Greek regional state or '' koinon'') consisting of all Maced ...

. With their mining and tax revenues, the kings were responsible for funding the military, which included a navy that was established by Philip II and expanded during the Antigonid period.

Sources and historiography

The earliest known government in ancient Macedonia was their monarchy, which lasted until 167 BC when it was abolished by the Romans.. Written evidence about Macedonian governmental institutions made before

The earliest known government in ancient Macedonia was their monarchy, which lasted until 167 BC when it was abolished by the Romans.. Written evidence about Macedonian governmental institutions made before Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

's reign is both rare and non-Macedonian in origin. The main sources of early Macedonian historiography are the works of Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, and Justin. Contemporary accounts given by those such as Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual pr ...

were often hostile and unreliable; even Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, who lived in Macedonia, provides us with terse accounts of its governing institutions. Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

was a contemporary historian who wrote about Macedonia, while later historians include Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus () was a Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alexandri Magni Macedon ...

, Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, and Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; la, Lucius Flavius Arrianus; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period.

''The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best ...

. The works of these historians affirm the hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is a form of government and succession of power in which the throne passes from one member of a ruling family to another member of the same family. A series of rulers from the same family would constitute a dynasty.

It is h ...

of Macedonia and basic institutions, yet it remains unclear if there was an established constitution for Macedonian government.; Contrary to Carol J. King, however, N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank write with apparent certainty and conviction when describing the Macedonian constitutional government restricting the king and involving a popular assembly

A popular assembly (or people's assembly) is a gathering called to address issues of importance to participants. Assemblies tend to be freely open to participation and operate by direct democracy. Some assemblies are of people from a location ...

of the army. . The main textual primary sources for the organization of Macedonia's military as it existed under Alexander the Great include Arrian, Quintus Curtius, Diodorus, and Plutarch, while modern historians rely mostly on Polybius and Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

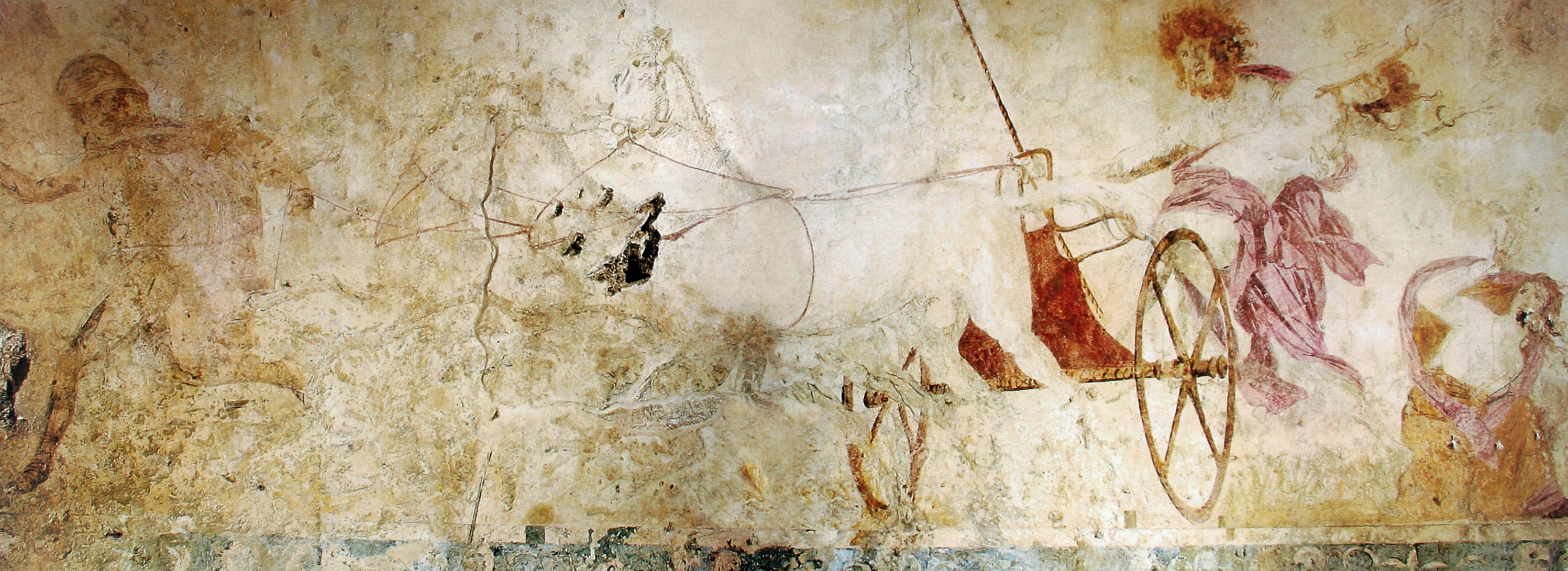

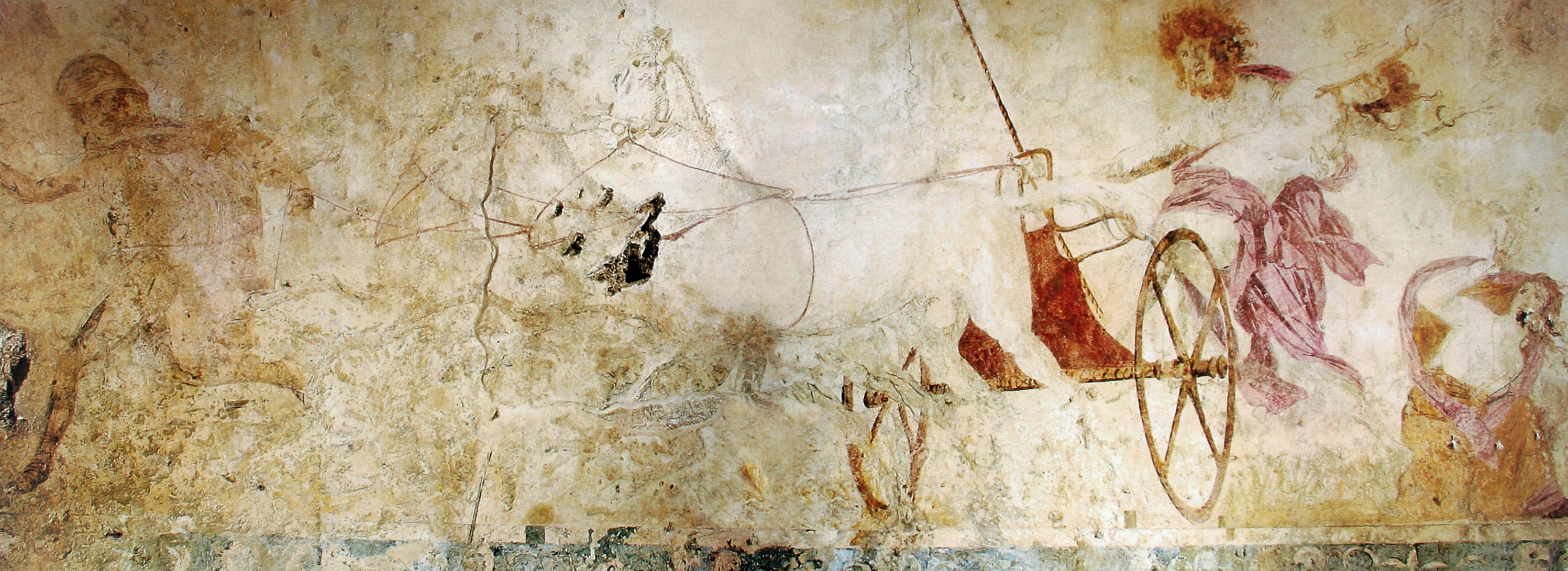

for understanding detailed aspects of the Antigonid-period military. writes the following: "... to this we can add the evidence provided by two magnificent archaeological monuments, the ' Alexander Sarcophagus' in particular and the 'Alexander Mosaic

The ''Alexander Mosaic,'' also known as the ''Battle of Issus Mosaic'', is a Roman floor mosaic originally from the House of the Faun in Pompeii (an alleged imitation of a Philoxenus of Eretria or Apelles' painting, 4th century BC) that dates ...

'... In the case of the Antigonid army ... valuable additional details are occasionally supplied by Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

and Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, and by a series of inscriptions preserving sections of two sets of army regulations issued by Philip V."

Division of power

At the head of Macedonia's government was the king (''

At the head of Macedonia's government was the king (''basileus

''Basileus'' ( el, ) is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs in history. In the English-speaking world it is perhaps most widely understood to mean " monarch", referring to either a " king" or an "emperor" and ...

''). From at least the reign of Philip II the king was assisted by the royal pages (''basilikoi paides''), bodyguards (''somatophylakes

''Somatophylakes'' ( el, Σωματοφύλακες; singular: ''somatophylax'', σωματοφύλαξ) were the bodyguards of high-ranking people in ancient Greece.

The most famous body of ''somatophylakes'' were those of Philip II of Macedon a ...

''), companions ('' hetairoi''), friends (''philoi ''Philoi'' ( grc, φίλοι; plural of φίλος ''philos'' "friend") is a word that roughly translates to "friend." This type of friendship is based on the characteristically Greek value for reciprocity as opposed to a friendship that exists as ...

''), an assembly that included members of the military, and magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

s during the Hellenistic period. Evidence is lacking for the extent to which each of these groups shared authority with the king or if their existence had a basis in a formal constitutional framework.; for an argument about the absolutism

Absolutism may refer to:

Government

* Absolute monarchy, in which a monarch rules free of laws or legally organized opposition

* Absolutism (European history), period c. 1610 – c. 1789 in Europe

** Enlightened absolutism, influenced by the En ...

of the Macedonian monarchy, see . Before the reign of Philip II, the only institution supported by textual evidence is the monarchy.. In 1931, Friedrich Granier was the first to propose that by the time of Philip II's reign, Macedonia had a constitutional government with laws that delegated rights and customary privileges to certain groups, especially to its citizen soldiers, although the majority of evidence for the army's alleged right to appoint a new king and judge cases of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

stems from the reign of Alexander III of Macedon

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to t ...

. Pietro De Francisci was the first to refute these ideas and advance the theory that the Macedonian government was an autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

ruled by the whim of the monarch, although this issue of kingship and governance is still unresolved in academia.

Institutions

Kingship and the royal court

The Macedonian hereditary monarchy existed since at least the time of

The Macedonian hereditary monarchy existed since at least the time of Archaic Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from circa 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the M ...

, perhaps evolving from a tribal system, and with roots in Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

in view of its seemingly Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

ic aristocratic attributes. Thucydides wrote that in previous ages Macedonia was divided into small tribal regions each having their own petty king, the tribes of Lower Macedonia eventually coalescing under one great king who exercised power as an overlord

An overlord in the English feudal system was a lord of a manor who had subinfeudated a particular manor, estate or fee, to a tenant. The tenant thenceforth owed to the overlord one of a variety of services, usually military service or ser ...

over the lesser kings of Upper Macedonia

Upper Macedonia ( Greek: Ἄνω Μακεδονία, ''Ánō Makedonía'') is a geographical and tribal term to describe the upper/western of the two parts in which, together with Lower Macedonia, the ancient kingdom of Macedon was roughly divide ...

.. The Argead dynasty lasted from the reign of Perdiccas I of Macedon until that of Alexander IV of Macedon

Alexander IV (Greek: ; 323/322– 309 BC), sometimes erroneously called Aegus in modern times, was the son of Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) and Princess Roxana of Bactria.

Birth

Alexander IV was the son of Alexander th ...

, supplanted by the Antigonid dynasty

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

during the Hellenistic period. The direct line of father-to-son succession was broken after the assassination of Orestes of Macedon in 396 BC (allegedly by his regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

and successor Aeropus II of Macedon

Aeropus II of Macedon ( grc, Ἀέροπος, Aéropos), king of Macedonia, son of Perdiccas II, was guardian during the minority of his nephew Orestes, with whom he reigned for some years after 399 BC.

The first four years of this time he reig ...

), clouding the issue of whether primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

was the established custom or if there was a constitutional right for an assembly of the army or of the people to choose another king. It is also unclear whether certain male offspring were considered more legitimate than others, since Archelaus I of Macedon

Archelaus I (; grc-gre, Ἀρχέλαος ) was a king of the kingdom of Macedonia from 413 to 399 BC. He was a capable and beneficent ruler, known for the sweeping changes he made in state administration, the military, and commerce. By the t ...

was the son of Perdiccas II of Macedon and a slave woman, although Archelaus succeeded the throne after murdering his father's designated heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

and son from another mother.

Historical sources confirm that the Macedonian kings before Philip II at least upheld the privileges and responsibilities of hosting foreign diplomats, initiating the kingdom's foreign policies, and negotiating deals such as alliances with foreign powers.. After the Greek victory at Salamis in 480 BC, the Persian commander Mardonius had Alexander I of Macedon

Alexander I of Macedon ( el, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μακεδών), known with the title Philhellene (Greek: φιλέλλην, literally "fond/lover of the Greeks", and in this context "Greek patriot"), was the ruler of the ancient Kingdom of ...

sent to Athens as a chief envoy to orchestrate an alliance between the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

and Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

. The decision to send Alexander was based on his marriage alliance with a noble Persian house and his previous formal relationship with the city-state of Athens. With their ownership of natural resources including gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, timber, and royal land

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it. ...

, the early Macedonian kings were also capable of bribing foreign and domestic parties with impressive gifts..

Little is known about the judicial system

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

of ancient Macedonia except that the king acted as the chief judge

A chief judge (also known as presiding judge, president judge or principal judge) is the highest-ranking or most senior member of a lower court or circuit court with more than one judge. According to the Federal judiciary of the United States, th ...

of the kingdom. The Macedonian kings were also supreme commanders of the military, with early evidence including not only Alexander I's role in the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

but also with the city-state of Potidaea

__NOTOC__

Potidaea (; grc, Ποτίδαια, ''Potidaia'', also Ποτείδαια, ''Poteidaia'') was a colony founded by the Corinthians around 600 BC in the narrowest point of the peninsula of Pallene, the westernmost of three peninsulas a ...

accepting Perdiccas II of Macedon as their commander during their rebellion against the Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pla ...

of Athens in 432 BC. In addition to the esteem won by serving as Macedonia's supreme commander, Philip II was also highly regarded for his acts of piety in serving as the high priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious caste.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many gods rev ...

of the nation. He performed daily ritual sacrifices and led religious festival

A religious festival is a time of special importance marked by adherents to that religion. Religious festivals are commonly celebrated on recurring cycles in a calendar year or lunar calendar. The science of religious rites and festivals is known ...

s.. Alexander imitated various aspects of his father's reign, such as granting land and gifts to loyal aristocratic followers. However, he lost some core support among them for adopting some of the trappings of an Eastern, Persian monarch, a "lord and master" as Carol J. King suggests, instead of a "comrade-in-arms" as was the traditional relationship of Macedonian kings with their companions. Yet it was his father Philip II who had already shown signs of being influenced by the Persian Empire when he adopted similar institutions, such as having a Royal Secretary, royal archive, royal pages, and a throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the mon ...

, although there is some scholarly debate as to the level of Persian influence in Philip's court.

Royal pages

The royal pages were adolescent boys and young men conscripted from aristocratic households and serving the kings of Macedonia perhaps from the reign of Philip II onward, although more solid evidence for their presence in the royal court dates to the reign of Alexander the Great.; According to Carol J. King, there was no "certain reference" to this institutional group until the military campaigns of Alexander the Great in Asia.However, N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank state that the royal pages are attested to as far back as the reign of

Archelaus I of Macedon

Archelaus I (; grc-gre, Ἀρχέλαος ) was a king of the kingdom of Macedonia from 413 to 399 BC. He was a capable and beneficent ruler, known for the sweeping changes he made in state administration, the military, and commerce. By the t ...

. . Royal pages played no direct role in high politics and were conscripted as a means to introduce them to political life.. After a period of training and service, pages were expected to become members of the king's companions and personal retinue.. During their training, pages were expected to guard the king as he slept, supply him with horses, aid him in mounting his horse, accompany him on royal hunts, and serve him during '' symposia'' (i.e. formal drinking parties). While conscripted pages would have looked forward to a lifelong career at court or even a prestigious post as a governor, they can also be regarded as hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or refr ...

s held by the royal court in order to ensure the loyalty and obedience of their aristocratic fathers.. The abusive punishment of pages, such as flogging, carried out by the king at times, led to intrigue and conspiracy against the Crown, as did the frequent homosexual relations between the pages and the elite, sometimes with the king. Although there is little evidence for royal pages throughout the Antigonid period, it is known that a group of them fled with Perseus of Macedon

Perseus ( grc-gre, Περσεύς; 212 – 166 BC) was the last king (''Basileus'') of the Antigonid dynasty, who ruled the successor state in Macedon created upon the death of Alexander the Great. He was the last Antigonid to rule Macedon, aft ...

to Samothrace

Samothrace (also known as Samothraki, el, Σαμοθράκη, ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. It is a municipality within the Evros regional unit of Thrace. The island is long and is in size and has a population of 2,859 (2011 ...

following his defeat by the Romans in 168 BC.

Bodyguards

Royal bodyguards served as the closest members to the king at court and on the battlefield. They were split into two categories: the ''agema

Agema ( el, Ἄγημα) is a term to describe a military detachment, used for a special cause, such as guarding high valued targets. Due to its nature the ''Agema'' most probably comprised elite troops.

Etymology

The word derives from the Greek ...

'' of the '' hypaspistai'', a type of ancient special forces

Special forces and special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equi ...

usually numbering in the hundreds, and a smaller group of men handpicked by the king either for their individual merits or to honor the noble families to which they belonged. Therefore, the bodyguards, limited in number and forming the king's inner circle, were not always responsible for protecting the king's life on and off the battlefield; their title and office was more a mark of distinction, perhaps used to quell rivalries between aristocratic houses.

Companions, friends, councils, and assemblies

The companions, including the elite

The companions, including the elite companion cavalry

The Companions ( el, , ''hetairoi'') were the elite cavalry of the Macedonian army from the time of king Philip II of Macedon, achieving their greatest prestige under Alexander the Great, and regarded as the first or among the first shock cava ...

and '' pezhetairoi'' infantry, represented a substantially larger group than the king's bodyguards.. The ranks of the companions were greatly increased during the reign of Philip II when he expanded this institution to include Upper Macedonia

Upper Macedonia ( Greek: Ἄνω Μακεδονία, ''Ánō Makedonía'') is a geographical and tribal term to describe the upper/western of the two parts in which, together with Lower Macedonia, the ancient kingdom of Macedon was roughly divide ...

n aristocrats as well as Greeks.. The most trusted or highest ranking companions formed a council that served as an advisory body to the king. A small amount of evidence also suggests that an assembly of the army during times of war and a people's assembly during times of peace existed in ancient Macedonia.. The first recorded instance dates to 359 BC, when Philip II called together a number of assemblies to address them with speech and raise their morale following the death of Perdiccas III of Macedon in battle against the Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

ns.

Members of the council had the right to speak their minds freely, and although there is no evidence that they voted on affairs of state or that the king was even obligated to implement their ideas, it is clear that he was at least occasionally pressured to do so. The assembly was apparently given the right to judge cases of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and assign punishments for them, such as when Alexander III acted as prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal tria ...

in the trial and ultimate conviction of three alleged conspirators in the plot to assassinate Philip II (while many others were acquitted). However, there is perhaps insufficient evidence to allow a conclusion that councils and assemblies were regularly upheld, constitutionally grounded, or that their decisions were always heeded by the king. At the death of Alexander the Great, the companions immediately formed a council to assume control of his empire; however, it was soon destabilized by open rivalry and conflict between its members. The army also used mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among memb ...

as a tool to achieve political ends. For instance, when Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to becom ...

had Philip II's daughter Cynane

Cynane ( el, Kυνάνη, ''Kynane'' or , ''Kyna''; killed 323 BC) was half-sister to Alexander the Great, and daughter of Philip II by Audata, an Illyrian princess. She is estimated to have been born in 357 BC.

Biography

According to Polyaenus ...

murdered to prevent her own daughter Eurydice II of Macedon from marrying Philip III of Macedon

Philip III Arrhidaeus ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος Ἀρριδαῖος ; c. 359 BC – 25 December 317 BC) reigned as king of Macedonia an Ancient Greek Kingdom in northern Greece from after 11 June 323 BC until his death. He was a son of King P ...

, the army revolted and ensured that the marriage took place.

Magistrates, the commonwealth, local government, and allied states

There is epigraphic evidence from the Hellenistic period and Antigonid dynasty that the Macedonian kingdom relied on various regional officials to conduct affairs of state.. This included a number of high-ranking municipal officials, including the military-rooted ''strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Helleni ...

'' and politarch, i.e. the elected governor (''archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

'') of a large city (''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

''), but also the politico-religious office of the ''epistates An ( gr, ἐπιστάτης, plural ἐπιστάται, ) in ancient Greece was any sort of superintendent or overseer. In the Hellenistic kingdoms generally, an is always connected with a subject district (a regional assembly), where the , as ...

''. Although these were highly influential members of local and regional government, Carol J. King asserts that they were not collectively powerful enough to formally challenge the authority of the Macedonian king or his right to rule. Robert Malcolm Errington

Robert Malcolm Errington (born 5 July 1939 in Howdon-on-Tyne), also known as R. Malcolm Errington, is a retired British historian who studied ancient Greece and the Classical world. He is a professor emeritus from Queen's University Belfast and t ...

affirms that no evidence exists about the personal backgrounds of these officials, although they may have been picked from the available aristocratic pools of ''philoi'' and ''hetairoi'' that were used to fill vacancies of officers in the army..

In ancient Athens

Athens is one of the oldest named cities in the world, having been continuously inhabited for perhaps 5,000 years. Situated in southern Europe, Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BC, and its cultural achieve ...

, the Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Although Athens is the most famous ancient Greek democratic ci ...

was restored on three separate occasions following the initial conquest of the city by Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

in 322 BC. However, when it fell repeatedly under Macedonian rule it was governed by a Macedonian-imposed oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

composed of the wealthiest members of the city-state, their membership determined by the value of their property.: under Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

's oligarchy, the lower value in terms of property for acceptable members of the oligarchy was 2,000 ''drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fr ...

''. Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Although Athens is the most famous ancient Greek democratic ci ...

was restored briefly after Antipater's death in 319 BC, yet his son Cassander

Cassander ( el, Κάσσανδρος ; c. 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and ''de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a conte ...

reconquered the city, which came under the regency of Demetrius of Phalerum

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; grc-gre, Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophrast ...

. Demetrius lowered the property limit for oligarchic members to 1,000 ''drachma'', yet by 307 BC he was exiled from the city and direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the electorate decides on policy initiatives without elected representatives as proxies. This differs from the majority of currently established democracies, which are repres ...

was restored. Demetrius I of Macedon reconquered Athens in 295 BC, yet democracy was once again restored in 287 BC with the aid of Ptolemy I of Egypt

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedon ...

. Antigonus II Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Γονατᾶς, ; – 239 BC) was a Macedonian ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for hi ...

, son of Demetrius I, reconquered Athens in 260 BC, followed by a succession of Macedonian kings ruling over Athens until the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

conquered both Macedonia and then mainland Greece by 146 BC. Yet other city-states were handled quite differently and were allowed a greater degree of autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one' ...

. After Philip II conquered Amphipolis

Amphipolis ( ell, Αμφίπολη, translit=Amfipoli; grc, Ἀμφίπολις, translit=Amphipolis) is a municipality in the Serres regional unit, Macedonia, Greece. The seat of the municipality is Rodolivos. It was an important ancient Gr ...

in 357 BC, the city was allowed to retain its democracy, including its constitution, popular assembly

A popular assembly (or people's assembly) is a gathering called to address issues of importance to participants. Assemblies tend to be freely open to participation and operate by direct democracy. Some assemblies are of people from a location ...

, city council

A municipal council is the legislative body of a municipality or local government area. Depending on the location and classification of the municipality it may be known as a city council, town council, town board, community council, rural coun ...

('' boule''), and yearly elections for new officials, but a Macedonian garrison was housed within the city walls along with a Macedonian royal commissioner (''epistates'') to monitor the city's political affairs. However, Philippi

Philippi (; grc-gre, Φίλιπποι, ''Philippoi'') was a major Greek city northwest of the nearby island, Thasos. Its original name was Crenides ( grc-gre, Κρηνῖδες, ''Krenides'' "Fountains") after its establishment by Thasian colo ...

, the city founded by Philip II, was the only other city in the Macedonian commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

that had a democratic government with popular assemblies, since the assembly (''ecclesia

Ecclesia (Greek: ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') may refer to:

Organizations

* Ecclesia (ancient Greece) or Ekklēsia, the principal assembly of ancient Greece during its Golden Age

* Ecclesia (Sparta), the citizens' assembly of Sparta, often w ...

'') of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

seems to have had only a passive function in practice. Some cities also maintained their own municipal revenue

In accounting, revenue is the total amount of income generated by the sale of goods and services related to the primary operations of the business.

Commercial revenue may also be referred to as sales or as turnover. Some companies receive rev ...

s, although evidence is lacking as to whether this was derived from local taxation or grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

s from the royal court.. The Macedonian king and central government otherwise sustained strict control over the finances administered by other cities, especially in regards to the revenues generated by temples and cultic priesthoods.

Within the Macedonian commonwealth, or the Koinon of Macedonians

The League of the Macedonians ( el, Κοινὸν τῶν Μακεδόνων, ''Koinòn tōn Makedónōn'') was a confederationally-organized commonwealth institution (i.e., an ancient Greek regional state or '' koinon'') consisting of all Maced ...

, there is some epigraphic evidence from the 3rd century BC that foreign relations were handled by the central government. Although Macedonian cities nominally participated in panhellenic events on their own accord, in reality the granting of '' asylia'' (inviolability, diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity is a principle of international law by which certain foreign government officials are recognized as having legal immunity from the jurisdiction of another country.

, and the right of asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another ent ...

at sanctuaries) to certain cities (e.g. Kyzikos in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

) was handled directly by the king or a preexisting regulation. Likewise, the city-states within contemporary Greek '' koina'' (i.e., federations of city-states, the ''sympoliteia

A ''sympoliteia'' ( gr, συμπολιτεία, , joint citizenship), anglicized as sympolity, was a type of treaty for political organization in ancient Greece. By the time of the Hellenistic period, it occurred in two forms. In mainland Greece, ...

'') obeyed the federal decrees vote

Voting is a method by which a group, such as a meeting or an electorate, can engage for the purpose of making a collective decision or expressing an opinion usually following discussions, debates or election campaigns. Democracies elect holde ...

d on collectively by the members of their league.Unlike the sparse Macedonian examples, ample textual evidence of this exists for the Achaean League

The Achaean League ( Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern P ...

, Acarnanian League, and Achaean League

The Achaean League ( Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern P ...

; see . In city-states belonging to a league or commonwealth, the granting of ''proxenia

Proxeny or ( grc-gre, προξενία) in ancient Greece was an arrangement whereby a citizen (chosen by the city) hosted foreign ambassadors at his own expense, in return for honorary titles from the state. The citizen was called (; plural: o ...

'' (i.e. the hosting of foreign ambassadors) was usually a right shared by local and central authorities. While there is plenty of surviving evidence that the granting of ''proxenia'' was the sole prerogative

In law, a prerogative is an exclusive right bestowed by a government or state and invested in an individual or group, the content of which is separate from the body of rights enjoyed under the general law. It was a common facet of feudal law. Th ...

of central authorities in the neighboring Epirote League, a small amount of evidence suggests the same arrangement in the Macedonian commonwealth. However, city-states that were allied with the Kingdom of Macedonia and existed outside of Macedonia proper issued their own decrees regarding ''proxenia''. Foreign leagues also formed alliances with the Macedonian kings, such as when the Cretan League signed treaties with Demetrius II Aetolicus and Antigonus III Doson

Antigonus III Doson ( el, Ἀντίγονος Γ΄ Δώσων, 263–221 BC) was king of Macedon from 229 BC to 221 BC. He was a member of the Antigonid dynasty.

Family background

Antigonus III Doson was a half-cousin of his predecessor, Demetr ...

ensuring enlistment of Cretan mercenaries into the Macedonian army, and elected Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon a ...

as honorary protector ('' prostates'') of the league..

Military

Early Macedonian army

The basic structure of the army was the division of the companion cavalry ('' hetairoi'') with the foot companions ('' pezhetairoi''), augmented by various allied troops, foreign levied soldiers, and mercenaries. The foot companions existed perhaps since the reign ofAlexander I of Macedon

Alexander I of Macedon ( el, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μακεδών), known with the title Philhellene (Greek: φιλέλλην, literally "fond/lover of the Greeks", and in this context "Greek patriot"), was the ruler of the ancient Kingdom of ...

, while Macedonian troops are accounted for in the history of Herodotus as subjects of the Persian Empire fighting the Greeks at the Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states (including Sparta, Athens, ...

in 479 BC. Macedonian cavalry, wearing muscled cuirasses, became renowned in Greece during and after their involvement in the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

(431–404 BC), at times siding with either Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

or Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

and supplemented by local Greek infantry instead of relying on Macedonian infantry. Macedonian infantry in this period consisted of poorly trained shepherd

A shepherd or sheepherder is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. ''Shepherd'' derives from Old English ''sceaphierde (''sceap'' 'sheep' + ''hierde'' ' herder'). ''Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations, ...

s and farmers, while the cavalry was composed of noblemen eager to win glory. An early 4th-century BC stone-carved relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

from Pella shows a Macedonian infantryman wearing a ''pilos'' helmet and wielding a short sword showing a pronounced Spartan influence on the Macedonian army before Philip II.. Nicholas Viktor Sekunda states that at the beginning of Philip II's reign in 359 BC, the Macedonian army consisted of 10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry, the latter figure similar to that recorded for the 5th century BC.. However, Malcolm Errington cautions that any figures for Macedonian troop sizes provided by ancient authors should be treated with a degree of skepticism, since there are very few means by which modern historians are capable of confirming their veracity (and could have been possibly lower or even higher than the amount stated).

Philip II and Alexander the Great

Imitating the Greek example of martial exercises and issuing of standard equipment for citizen soldiery, Philip II transformed the Macedonian army from a levied force of unprofessional farmers into a well-trained fighting force. writes the following: "the crucial necessity ofdrill

A drill is a tool used for making round holes or driving fasteners. It is fitted with a bit, either a drill or driver chuck. Hand-operated types are dramatically decreasing in popularity and cordless battery-powered ones proliferating due to ...

ing troops must have become clear to Philip at the latest during his time as a hostage in Thebes." Philip II's infantry wielded ''peltai'' shields that already disembarked from the ''aspis

An aspis ( grc, ἀσπίς, plural ''aspides'', ), or porpax shield, sometimes mistakenly referred to as a hoplon ( el, ὅπλον) (a term actually referring to the whole equipment of a hoplite), was the heavy wooden shield used by the i ...

'' style shield featured in sculpted artwork of a Katerini

Katerini ( el, Κατερίνη, ''Kateríni'', ) is a city and municipality in northern Greece, the capital city of Pieria regional unit in Central Macedonia, Greece. It lies on the Pierian plain, between Mt. Olympus and the Thermaikos Gulf, ...

tomb dated perhaps to the reign of Amyntas III of Macedon

Amyntas III (Greek: Αμύντας Γ΄ της Μακεδονίας) (420 – 370 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia in 393 BC and again from 392 to 370 BC. He was the son of Arrhidaeus and grandson of Amyntas, one of the sons ...

. His early infantry were also equipped with protective helmets and greave

A greave (from the Old French ''greve'' "shin, shin armour") or jambeau is a piece of armour that protects the leg.

Description

The primary purpose of greaves is to protect the tibia from attack. The tibia, or shinbone, is very close to the sk ...

s, as well as '' sarissa'' pikes, yet according to Sekunda they were eventually equipped with heavier armor such as cuirass

A cuirass (; french: cuirasse, la, coriaceus) is a piece of armour that covers the torso, formed of one or more pieces of metal or other rigid material. The word probably originates from the original material, leather, from the French '' cuirac ...

es, since the ''Third Philippic The "Third Philippic" was delivered by the prominent Athenian statesman and orator, Demosthenes, in 341 BC. It constitutes the third of the four philippics.

Historical background

In 343 BC, the Macedonian arms were carried across Epirus and a year ...

'' of Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual pr ...

in 341 BC described them as hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

s instead of lighter peltast

A ''peltast'' ( grc-gre, πελταστής ) was a type of light infantryman, originating in Thrace and Paeonia, and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon in the Anabasis disting ...

s. As evidenced by the Alexander Sarcophagus, troops serving Alexander the Great were also armored in the hoplite fashion.. However, Errington argues that breastplate

A breastplate or chestplate is a device worn over the torso to protect it from injury, as an item of religious significance, or as an item of status. A breastplate is sometimes worn by mythological beings as a distinctive item of clothing. It is ...

s were not worn by the phalanx

The phalanx ( grc, φάλαγξ; plural phalanxes or phalanges, , ) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar pole weapons. The term is particularly ...

pikemen

A pike is a very long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages and most of the Early Modern Period, and were wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayon ...

of either Philip II or Philip V's reign periods (during which sufficient evidence exists).. Instead, he claims that breastplates were only worn by military officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent context ...

s, while pikemen wore the '' kotthybos'' stomach bands along with their helmets and greaves, wielding a dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or popular-use def ...

as a secondary weapon along with their shield

A shield is a piece of personal armour held in the hand, which may or may not be strapped to the wrist or forearm. Shields are used to intercept specific attacks, whether from close-ranged weaponry or projectiles such as arrows, by means of ...

s.

The elite '' hypaspistai'' infantry, composed of handpicked men from the ranks of the ''pezhetairoi'' and perhaps synonymous with earlier ''doryphoroi'', were formed during the reign of Philip II and saw continued use during the reign of Alexander the Great. Philip II was also responsible for the establishment of the royal bodyguards (''somatophylakes

''Somatophylakes'' ( el, Σωματοφύλακες; singular: ''somatophylax'', σωματοφύλαξ) were the bodyguards of high-ranking people in ancient Greece.

The most famous body of ''somatophylakes'' were those of Philip II of Macedon a ...

'') and royal pages (''basilikoi paides'').. Philip II was also able to field archer

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In m ...

s, including mercenary Cretan archers and perhaps some native Macedonians. It is unclear if the Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

, Paionians, and Illyrians

The Illyrians ( grc, Ἰλλυριοί, ''Illyrioi''; la, Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan populations, a ...

fighting as javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the ...

throwers, slingers, and archers serving in Macedonian armies from the reign of Philip II onward were conscripted as allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

via a treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal per ...

or were simply hired mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes Pseudonym, also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a memb ...

. Philip II hired engineers such as Polyidus of Thessaly

Polyidus of Thessaly (also Polyides, Polydus; , , English translation: "much beauty", from ''polus'', "many, much" and ''eidos'', "form, appearance, beauty") was an ancient Greek military engineer of Philip, who made improvements in the covered b ...

and Diades of Pella, who were capable of building state of the art

The state of the art (sometimes cutting edge or leading edge) refers to the highest level of general development, as of a device, technique, or scientific field achieved at a particular time. However, in some contexts it can also refer to a level ...

siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while oth ...

s and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

firing large bolts. Following the acquisition of the lucrative mines at Krinides

Krinides ( el, Κρηνίδες, before 1926: Ράχτσα - ''Rachtsa'') is a town in the Kavala regional unit in eastern Macedonia, Greece. It was the seat of the former municipality of Filippoi. The ruins of the ancient city Philippi are clos ...

(renamed Philippi

Philippi (; grc-gre, Φίλιπποι, ''Philippoi'') was a major Greek city northwest of the nearby island, Thasos. Its original name was Crenides ( grc-gre, Κρηνῖδες, ''Krenides'' "Fountains") after its establishment by Thasian colo ...

), the royal treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

could afford to field a permanent, professional standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or ...

. The increase in state revenues allowed the Macedonians to build a small navy for the first time, which included trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

s. Although it did not succeed in every battle, the army of Philip II was able to successfully adopt the military tactics

Military tactics encompasses the art of organizing and employing fighting forces on or near the battlefield. They involve the application of four battlefield functions which are closely related – kinetic or firepower, Mobility (military), mobil ...

of its enemies, such as the '' embolon'' (i.e. 'flying wedge') formation of the Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

ns.. This offered cavalry far greater maneuverability and an edge in battle that previously did not exist in the Classical Greek world.

During the reign of Alexander the Great, the only Macedonian cavalry units attested in battle were the companion cavalry. However, during his campaign in Asia against the Persian Empire he formed a '' hipparchia'' (i.e. unit of a few hundred horsemen) of companion cavalry composed entirely of ethnic

During the reign of Alexander the Great, the only Macedonian cavalry units attested in battle were the companion cavalry. However, during his campaign in Asia against the Persian Empire he formed a '' hipparchia'' (i.e. unit of a few hundred horsemen) of companion cavalry composed entirely of ethnic Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian. ...

.. When marching his forces into Asia, Alexander brought 1,800 cavalrymen from Macedonia, 1,800 cavalrymen from Thessaly, 600 cavalrymen from the rest of Greece, and 900 ''prodromoi

In ancient Greece, the ''prodromoi'' (singular: ''prodromos'') were skirmisher light cavalry. Their name ( ancient Greek: ''πρόδρομοι'', ''prοdromoi'', lit. "pre-cursors," "runners-before," or "runners-ahead") implies that these cavalry ...

'' cavalry from Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

.. Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

was able to quickly levy 600 native Macedonian cavalry to fight in the Lamian War

The Lamian War, or the Hellenic War (323–322 BC) was fought by a coalition of cities including Athens and the Aetolian League against Macedon and its ally Boeotia. The war broke out after the death of the King of Macedon, Alexander the Great, ...

when it began in 323 BC. For his infantry, the most elite members of his ''hypaspistai'' were designated as the ''agema

Agema ( el, Ἄγημα) is a term to describe a military detachment, used for a special cause, such as guarding high valued targets. Due to its nature the ''Agema'' most probably comprised elite troops.

Etymology

The word derives from the Greek ...

'', yet a new term for ''hypaspistai'' emerged after the Battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

in 331 BC: the '' argyraspides'' ('silver shields'). The latter continued to serve after the reign of Alexander the Great and may have been of Asian origin.; see also : in regards to both the '' argyraspides'' and '' chalkaspides'', "these titles were probably not functional, perhaps not even official." Overall, his pike-wielding infantry numbered some 12,000 men, 3,000 of which were elite ''hypaspistai'' and 9,000 of which were ''pezhetairoi''.; In contrast to Nicholas V. Sekunda and in discussing the discrepancies among ancient historians

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

about the size of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

's army, N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank choose Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

' figure of 32,000 infantry as the most reliable, while disagreeing with his figure for cavalry at 4,500, asserting it was closer to 5,100 horsemen. . Alexander continued the use of Cretan archers, yet around this time a clear reference to the use of native Macedonian archers was made. After the Battle of Gaugamela, archers of West Asian backgrounds became commonplace and were organized into '' chiliarchs''..

Antigonid period military

The Macedonian army continued to evolve under theAntigonid dynasty

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

. It is uncertain how many men were appointed as ''somatophylakes'', which numbered eight men at the end of Alexander the Great's reign, while the ''hypaspistai'' seem to have morphed into assistants of the ''somatophylakes'' rather than a separate unit in their own right.; : "Other developments in Macedonian army organization are evident after Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

. One is the evolution of the '' hypaspistai'' from an elite unit to a form of military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear rec ...

or bodyguard

A bodyguard (or close protection officer/operative) is a type of security guard, government law enforcement officer, or servicemember who protects a person or a group of people — usually witnesses, high-ranking public officials or officers, ...

under Philip V; the only thing the two functions had in common was the particular closeness to the king." At the Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae ( el, Μάχη τῶν Κυνὸς Κεφαλῶν) was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Phil ...

in 197 BC, the Macedonians commanded some 16,000 phalanx

The phalanx ( grc, φάλαγξ; plural phalanxes or phalanges, , ) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar pole weapons. The term is particularly ...

pikemen

A pike is a very long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages and most of the Early Modern Period, and were wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayon ...

.. Alexander the Great's 'royal squadron' of companion cavalry were similarly numbered to the 800 cavalrymen of the 'sacred squadron' (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

: ''sacra ala''; Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: ''hiera ile'') commanded by Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon a ...

during the Social War of 219 BC.. Due to the Roman historian Livy's accounts of the battles of Callinicus Callinicus or Kallinikos ( el, Καλλίνικος) is a surname or male given name; the feminine form is Kalliniki, Callinice or Callinica ( el, Καλλινίκη). It is of Greek origin, meaning "beautiful victor".

People named Callinicus Seleu ...

in 171 BC and Pydna in 168 BC, it is known that the Macedonian cavalry were also divided into groups with similarly named officers as had existed in Alexander's day. The regular Macedonian cavalry numbered 3,000 at Callinicus, which was separate from the 'sacred squadron' and 'royal cavalry'. While Macedonian cavalry of the 4th century BC had fought without shields, the use of shields by cavalry was adopted from the Celtic invaders of the 270s BC who settled in Galatia