Gorgonopsia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gorgonopsia (from the Greek

Earlier gorgonopsids in the Middle Permian were quite small, with skull lengths of , whereas some later genera attained massive, bear-like sizes with the largest being '' Inostrancevia'' up to in length and in body mass. Nonetheless, small gorgonopsians remained abundant until extinction (though small species may actually represent juvenile specimens of other taxa).

Like other Permian therapsids, gorgonopsians had developed several mammalian characteristics. These might have included a parasagittal gait (the limbs were vertically oriented and moved parallel to the spine) as opposed to the sprawling gait of

Earlier gorgonopsids in the Middle Permian were quite small, with skull lengths of , whereas some later genera attained massive, bear-like sizes with the largest being '' Inostrancevia'' up to in length and in body mass. Nonetheless, small gorgonopsians remained abundant until extinction (though small species may actually represent juvenile specimens of other taxa).

Like other Permian therapsids, gorgonopsians had developed several mammalian characteristics. These might have included a parasagittal gait (the limbs were vertically oriented and moved parallel to the spine) as opposed to the sprawling gait of

The gorgonopsian brain, like other non- mammaliaform

The gorgonopsian brain, like other non- mammaliaform

Like many mammals, gorgonopsians were

Like many mammals, gorgonopsians were

The seven

The seven

In 1876, the first gorgonopsian remains were identified in the

In 1876, the first gorgonopsian remains were identified in the  Gorgonopsians were first identified in

Gorgonopsians were first identified in

Upon discovery, Owen presumed that ''Gorgonops'' and several other taxa he described from the Karoo Supergroup were cold-blooded reptiles, despite bearing teeth resembling those of carnivorous mammals. He proposed classifying all of them under the newly coined

Upon discovery, Owen presumed that ''Gorgonops'' and several other taxa he described from the Karoo Supergroup were cold-blooded reptiles, despite bearing teeth resembling those of carnivorous mammals. He proposed classifying all of them under the newly coined  Among the first attempts to organise the clade was carried out by British zoologist David Meredith Seares Watson and American palaeontologist

Among the first attempts to organise the clade was carried out by British zoologist David Meredith Seares Watson and American palaeontologist

The Permian progressively became dryer and dryer. In the Upper Carboniferous and Lower Permian, pelycosaurs seem to have clung to the everwet

The Permian progressively became dryer and dryer. In the Upper Carboniferous and Lower Permian, pelycosaurs seem to have clung to the everwet

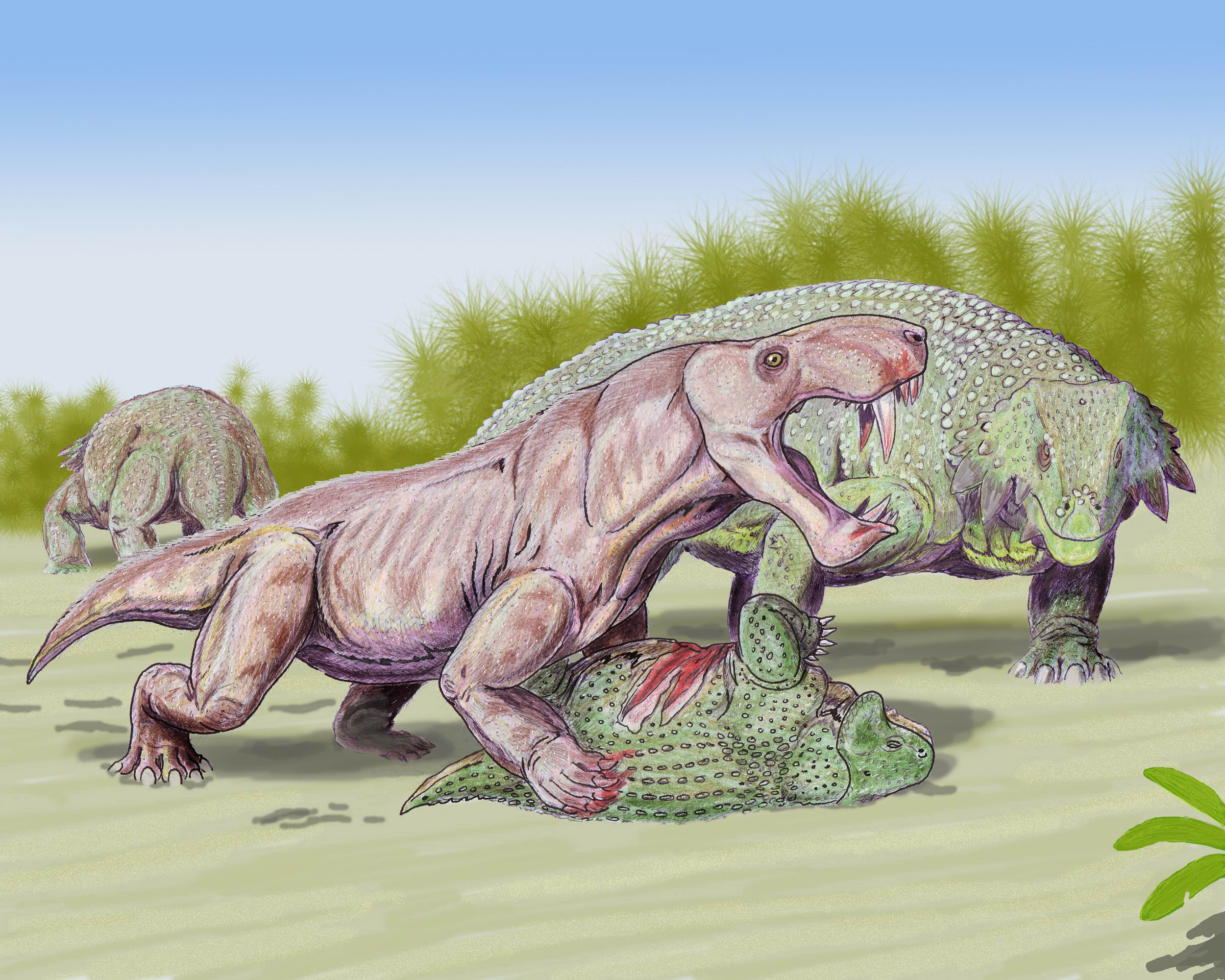

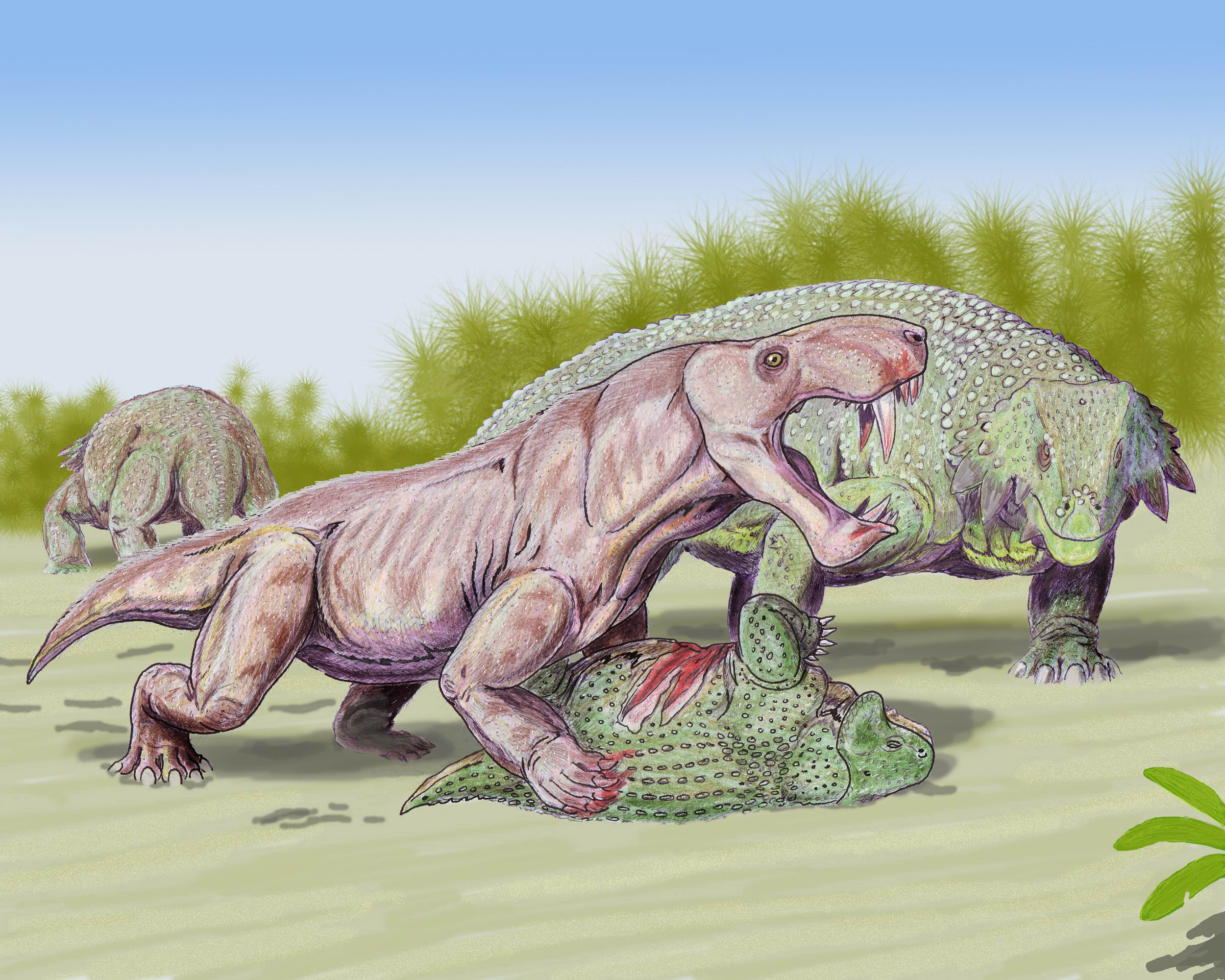

Gorgonopsians were likely active predators. The rubidgeines have an especially robust skull among gorgonopsians, comparable to those of enormous macropredators which use their skulls as their primary weapon, such as

Gorgonopsians were likely active predators. The rubidgeines have an especially robust skull among gorgonopsians, comparable to those of enormous macropredators which use their skulls as their primary weapon, such as  Gorgonopsians, along with other early carnivores as well as crocodiles, predominantly relied on "Kinetic-Inertial system" (KI) of biting down onto prey, in which the pterygoid and

Gorgonopsians, along with other early carnivores as well as crocodiles, predominantly relied on "Kinetic-Inertial system" (KI) of biting down onto prey, in which the pterygoid and

Gorgonopsians are considered to have been strictly terrestrial. They are thought to have been able to move with an erect gait similar to that used by crocodilians, the limbs positioned almost vertically as opposed to horizontally as in the sprawling gait of lizards. The glenoid cavity on the shoulder blade is strongly angled tailwards, so the limbs had limited forward movement, and they may have had a short stride length. Lizards often move their spines side to side to increase stride length, but the more vertically orientated

Gorgonopsians are considered to have been strictly terrestrial. They are thought to have been able to move with an erect gait similar to that used by crocodilians, the limbs positioned almost vertically as opposed to horizontally as in the sprawling gait of lizards. The glenoid cavity on the shoulder blade is strongly angled tailwards, so the limbs had limited forward movement, and they may have had a short stride length. Lizards often move their spines side to side to increase stride length, but the more vertically orientated  In regard to how the feet were placed on the ground, gorgonopsians are the only early therapsids which present ectataxony (the last digit bears the most weight), homopody (footprints and handprints look the same), and semi-plantigrady (to some degree, the feet were placed flat on the ground). These adaptations may have made gorgonopsians swifter and more agile than their prey. Gorgonopsians had rather nimble digits, indicative of grasping capability for both the hands and feet, possibly for grappling struggling prey to prevent excessive load bearing on, and consequential fracturing or breaking of, the canines while they were sunk into the victim.

In regard to how the feet were placed on the ground, gorgonopsians are the only early therapsids which present ectataxony (the last digit bears the most weight), homopody (footprints and handprints look the same), and semi-plantigrady (to some degree, the feet were placed flat on the ground). These adaptations may have made gorgonopsians swifter and more agile than their prey. Gorgonopsians had rather nimble digits, indicative of grasping capability for both the hands and feet, possibly for grappling struggling prey to prevent excessive load bearing on, and consequential fracturing or breaking of, the canines while they were sunk into the victim.

Unlike eutheriodonts, but like some ectothermic creatures today, all gorgonopsians possessed a pineal eye on the top of the head, which is used to detect daylight (and thus, the optimal temperature to be active). It is possible that other theriodonts lost this due to the evolution of either endothermy, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the eyes—in tandem with the loss of colour vision and a shift to nocturnal life–or both.

Unlike eutheriodonts, but like some ectothermic creatures today, all gorgonopsians possessed a pineal eye on the top of the head, which is used to detect daylight (and thus, the optimal temperature to be active). It is possible that other theriodonts lost this due to the evolution of either endothermy, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the eyes—in tandem with the loss of colour vision and a shift to nocturnal life–or both.  Early theriodonts (including gorgonopsians) may have possessed an

Early theriodonts (including gorgonopsians) may have possessed an

Following the extinction of the dinocephalians and (in South Africa) the basal therocephalians

Following the extinction of the dinocephalians and (in South Africa) the basal therocephalians

Gorgon

A Gorgon ( /ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ ''Gorgṓn/Gorgṓ'') is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the te ...

, a mythological beast, and 'aspect') is an extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

of sabre-toothed therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

s from the Middle to Upper Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

roughly 265 to 252 million years ago. They are characterised by a long and narrow skull, as well as elongated upper and sometimes lower canine teeth

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dog teeth, or (in the context of the upper jaw) fangs, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or vampire fangs, are the relatively long, pointed teeth. They can appear more flattened howeve ...

and incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s which were likely used as slashing and stabbing weapons. Postcanine teeth are generally reduced or absent. For hunting large prey, they possibly used a bite-and-retreat tactic, ambushing and taking a debilitating bite out of the target, and following it at a safe distance before its injuries exhausted it, whereupon the gorgonopsian would grapple the animal and deliver a killing bite. They would have had an exorbitant gape, possibly in excess of 90°, without having to unhinge the jaw.

They markedly increased in size as time went on, growing from small skull lengths of in the Middle Permian to bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae. They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the No ...

-like proportions of up to in the Upper Permian. The latest gorgonopsians, Rubidgeinae, were the most robust

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

of the group and could produce especially powerful bites. Gorgonopsians are thought to have been completely terrestrial and could walk with a semi-erect gait, with a similar terrestrial locomotory range as modern crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livi ...

ns. They may have been more agile than their prey items, but were probably inertial homeotherms rather than endotherms unlike contemporary therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct suborder of eutheriodont therapsids (mammals and their close relatives) from the Permian and Triassic. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of thei ...

ns and cynodont

The cynodonts () (clade Cynodontia) are a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Cynodonts had a wide varie ...

s, and thus were probably comparatively less active. Though gorgonopsians were able to maintain a rather high body temperature, it is unclear if they would have also had sweat gland

Sweat glands, also known as sudoriferous or sudoriparous glands, , are small tubular structures of the skin that produce sweat. Sweat glands are a type of exocrine gland, which are glands that produce and secrete substances onto an epithelial ...

s or fur (and by extension whisker

Vibrissae (; singular: vibrissa; ), more generally called Whiskers, are a type of stiff, functional hair used by mammals to sense their environment. These hairs are finely specialised for this purpose, whereas other types of hair are coars ...

s and related structures). Their brains were reminiscent of modern reptilian brains, rather than those of living mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s. Most species may have been predominantly diurnal (active during the day) though some could have been crepuscular

In zoology, a crepuscular animal is one that is active primarily during the twilight period, being matutinal, vespertine, or both. This is distinguished from diurnal and nocturnal behavior, where an animal is active during the hours of dayli ...

(active at dawn or dusk) or nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

(active at night). They are thought to have had binocular vision

In biology, binocular vision is a type of vision in which an animal has two eyes capable of facing the same direction to perceive a single three-dimensional image of its surroundings. Binocular vision does not typically refer to vision where an ...

, a parietal eye

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhyth ...

(which detects sunlight and maintains circadian rhythm

A circadian rhythm (), or circadian cycle, is a natural, internal process that regulates the sleep–wake cycle and repeats roughly every 24 hours. It can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., endogenous) and responds to ...

), a keen sense of smell, a functional vomeronasal organ

The vomeronasal organ (VNO), or Jacobson's organ, is the paired auxiliary olfactory (smell) sense organ located in the soft tissue of the nasal septum, in the nasal cavity just above the roof of the mouth (the hard palate) in various tetrapo ...

("Jacobson's organ"), and possibly a rudimentary eardrum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit sound from the ...

.

The major therapsid groups had all evolved by 275 million years ago from a "pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is ...

" ancestor (a poorly defined group including all synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

s which are not therapsids). The therapsid takeover from pelycosaurs took place by the Middle Permian as the world progressively became drier. Gorgonopsians rose to become apex predators

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

of their environments following the Capitanian mass extinction event

The Capitanian mass extinction event, also known as the end-Guadalupian extinction event or the pre-Lopingian crisis was an extinction event that predated the end-Permian extinction event and occurred around 260 million years ago during a period ...

which killed off the dinocephalians

Dinocephalians (terrible heads) are a clade of large-bodied early therapsids that flourished in the Early and Middle Permian between 279.5 and 260 million years ago (Ma), but became extinct during the Capitanian mass extinction event. Dinoceph ...

and some large therocephalians after the Middle Permian. Despite the existence of a single continent during the Permian, Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

, gorgonopsians have only been found in the Karoo Supergroup

The Karoo Supergroup is the most widespread stratigraphic unit in Africa south of the Kalahari Desert. The supergroup consists of a sequence of units, mostly of nonmarine origin, deposited between the Late Carboniferous and Early Jurassic, a peri ...

(primarily in South Africa, but also in Tanzania, Zambia, and Malawi), the Moradi Formation of Niger, western Russia, and in the Turpan Basin

The Turpan Depression or Turfan Depression, is a fault-bounded trough located around and south of the city-oasis of Turpan, in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in far Western China, about southeast of the regional capital Ürümqi. It includes ...

of Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, with probable remains known from the Kundaram Formation in the Pranhita–Godavari Basin of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

. These places were semi-arid areas with highly seasonal rainfall. Gorgonopsian genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

are all very similar in appearance, and consequently many species have been named based on flimsy and likely age-related differences since their discovery in the late 19th century, and the group has been subject to several taxonomic revisions.

They became extinct during a phase of the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, ...

taking place at the very end of the Permian, in which major volcanic activity (which would produce the Siberian Traps

The Siberian Traps (russian: Сибирские траппы, Sibirskiye trappy) is a large region of volcanic rock, known as a large igneous province, in Siberia, Russia. The massive eruptive event that formed the traps is one of the largest ...

) and resultant massive spike in greenhouse gas

A greenhouse gas (GHG or GhG) is a gas that absorbs and emits radiant energy within the thermal infrared range, causing the greenhouse effect. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are water vapor (), carbon dioxide (), methane ...

es caused rapid aridification due to temperature spike, acid rain

Acid rain is rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). Most water, including drinking water, has a neutral pH that exists between 6.5 and 8.5, but ac ...

, frequent wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identi ...

s, and potential breakdown of the ozone layer

The ozone layer or ozone shield is a region of Earth's stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. It contains a high concentration of ozone (O3) in relation to other parts of the atmosphere, although still small in rel ...

. The large predatory niches would be taken over by the archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avia ...

s (namely crocodilians and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s) in the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

.

Description

Earlier gorgonopsids in the Middle Permian were quite small, with skull lengths of , whereas some later genera attained massive, bear-like sizes with the largest being '' Inostrancevia'' up to in length and in body mass. Nonetheless, small gorgonopsians remained abundant until extinction (though small species may actually represent juvenile specimens of other taxa).

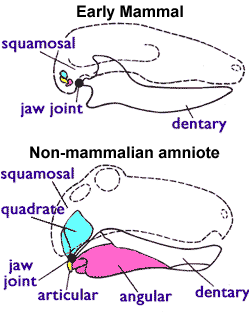

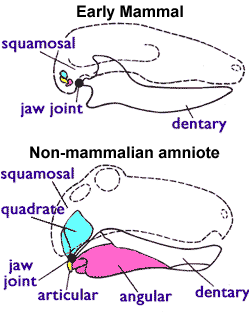

Like other Permian therapsids, gorgonopsians had developed several mammalian characteristics. These might have included a parasagittal gait (the limbs were vertically oriented and moved parallel to the spine) as opposed to the sprawling gait of

Earlier gorgonopsids in the Middle Permian were quite small, with skull lengths of , whereas some later genera attained massive, bear-like sizes with the largest being '' Inostrancevia'' up to in length and in body mass. Nonetheless, small gorgonopsians remained abundant until extinction (though small species may actually represent juvenile specimens of other taxa).

Like other Permian therapsids, gorgonopsians had developed several mammalian characteristics. These might have included a parasagittal gait (the limbs were vertically oriented and moved parallel to the spine) as opposed to the sprawling gait of amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

s and earlier synapsids. This gait change in therapsids was possibly related to the reduction in tail size and phalangeal formula (the number of bones per digit, which for gorgonopsians was 2.3.4.5.3 like reptiles). Other developments included fibrous lamellar cortical bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and ...

and deeply-set teeth. Like reptiles, gorgonopsians lack a secondary palate

The secondary palate is an anatomical structure that divides the nasal cavity from the oral cavity in many vertebrates.

In human embryology, it refers to that portion of the hard palate that is formed by the growth of the two palatine shelves medi ...

separating the mouth from the nasal cavity, prohibiting chewing.

Skull

Anatomy varies incredibly little between gorgonopsians. Many species are distinguished by vague proportional differences, and consequently smaller species may actually represent juveniles of larger taxa. Notably, thevomer

The vomer (; lat, vomer, lit=ploughshare) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right max ...

at the tip of the snout varies among species in terms of the degree of its expansion, as well as the positions, degree of splay, and shape of the 3 ridges. They typically feature a long and narrow skull. Juvenile ''Rubidgea'' appear to have had snouts wider than long. Unlike eutheriodonts, the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobes of the cer ...

(at the back of the skull) is rectangular (wider than tall) and concave, as opposed to triangular.

The gorgonopsian brain, like other non- mammaliaform

The gorgonopsian brain, like other non- mammaliaform therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

s, lacks an expansion of the neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, sp ...

, has a relatively large hindbrain compared to the forebrain, a large epyphysial nerve (found in creatures with a parietal eye

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhyth ...

on the top of the head), an enlarged pituitary gland

In vertebrate anatomy, the pituitary gland, or hypophysis, is an endocrine gland, about the size of a chickpea and weighing, on average, in humans. It is a protrusion off the bottom of the hypothalamus at the base of the brain. The h ...

, and an overall elongated shape; all-in-all resembling a reptilian brain. The braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, or brain-pan is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calvaria or skul ...

was also rather reptilian, and is also comparatively smaller and not as thick as those of mammals. The flocculus

The flocculus (Latin: ''tuft of wool'', diminutive) is a small lobe of the cerebellum at the posterior border of the middle cerebellar peduncle anterior to the biventer lobule. Like other parts of the cerebellum, the flocculus is involved in moto ...

, a lobe of the cerebellum

The cerebellum (Latin for "little brain") is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as or even larger. In humans, the cerebe ...

, is proportionally large, and is related to the vestibulo–ocular reflex (which stabilises gaze while moving the head). Judging by the orientation of the semi-circular canal

The semicircular canals or semicircular ducts are three semicircular, interconnected tubes located in the innermost part of each ear, the inner ear. The three canals are the horizontal, superior and posterior semicircular canals.

Structure

The ...

s in the ear (which have to be oriented parallel to the ground), the head of the gorgonopsian specimen GPIT/RE/7124 would have tilted forward by about 41°, increasing the overlap between the visual fields of the two eyes and improving binocular vision

In biology, binocular vision is a type of vision in which an animal has two eyes capable of facing the same direction to perceive a single three-dimensional image of its surroundings. Binocular vision does not typically refer to vision where an ...

– useful to a predator. Unlike either reptiles or mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s, the semi-circular canals are flat, probably because they were wedged between the opisthotic (an inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in th ...

bone) and supraoccipital bones.

Teeth

Like many mammals, gorgonopsians were

Like many mammals, gorgonopsians were heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For exampl ...

s, with clearly defined incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s, canines, and postcanine teeth homologous with premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

s and molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone to ...

. They had five incisors in the upper jaw (for most, the first three were the same size as each other, and the last two were shorter) and four on the bottom.

In the majority of gorgonopsians, the incisors were large, and the upper canines were elongated into sabres, much like those of later sabre-toothed cat

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae (true cats). They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million unt ...

s. Some gorgonopsians had exceptionally long upper canines, such as '' Inostrancevia'', and some of them had a flange on the lower jaw to sheath the tip of the canine while the mouth was closed. Sabres are generally interpreted as having been used as stabbing or slashing weapons, which would have required an extremely wide gape. Both the upper and lower canines of '' Rubidgea'' were elongated, and the animal would have needed an even greater gape. The serration pattern of gorgonopsians was most similar to those of theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s than to other synapsids. The palate also features tuberosities and ridges which oftentimes have functional teeth, which may have been used to hold onto struggling prey, diverting these powerful forces away from the fragile canines. Similar ridges have been identified on the machairodont

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae (true cats). They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million until ...

''Homotherium

''Homotherium'', also known as the scimitar-toothed cat or scimitar cat, is an extinct genus of machairodontine saber-toothed predator, often termed scimitar-toothed cats, that inhabited North America, South America, Eurasia, and Africa during ...

''. The postcanine teeth were reduced in both size and number; many rubidgeines (the latest gorgonopsians) did not have postcanines in the lower jaw, and ''Clelandina

''Clelandina'' is an extinct genus of rubidgeine gorgonopsian from the Late Permian of ''Cistecephalus'' Assemblage Zone of South Africa. It was first named by Broom in 1948. The type and only species is ''C. rubidgei''. It is relatively ...

'' lacked them entirely.

Gorgonopsians were polyphyodont

A polyphyodont is any animal whose teeth are continually replaced. In contrast, diphyodonts are characterized by having only two successive sets of teeth.

Polyphyodonts include most toothed fishes, many reptiles such as crocodiles and geckos, ...

s, and teeth grew continuously throughout an individual's life. Like some therapsids, while there was one functional canine, another canine was growing to replace it when it inevitably broke off. The left and right sides of the jaws did not have to be synchronous, so, for example, the first canine on the left side could be functional while the first canine on the right side was still growing. Such a method might have been in play so as always to have a set of functional canines, as having a single or no canines would have severely impeded hunting, and growing such large teeth took a long time. On the other hand, because the functional canine is typically found in the foremost tooth socket (instead of equal occurrence in either socket), it is possible that canine replacement occurred a finite number of times, and the animal would eventually be left with a single, permanent set of functional canines in these sockets. In 1984, British palaeontologists Doris and Kenneth Kermack suggested that the canines grew to match the size of the skull, and continually broke off until the animal stopped growing, and that gorgonopsians featured an early version of finite tooth replacement exhibited in many mammals. The tooth replacement patterns of the other teeth are unclear. The postcanine teeth were replaced more slowly than the other teeth, likely due to their lack of functional significance.

Postcranium

The seven

The seven cervical vertebra

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In sa ...

e (in the neck) are all the same size as each other except for the last one, which is shorter and lower; there is one atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geogra ...

and one axis. Like sabre-toothed cats, the neck is long with well developed muscles, which would have been especially useful when the canines were sunk into an animal. Like other early synapsids, gorgonopsians have a single occipital condyle

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape, and their anteri ...

, and the articulation (the joints) of the cervical vertebrae is overall reptilian, permitting side-to-side movement of the head but restricting up-and-down motion. The last cervical is shaped more like the dorsal vertebrae.

The dorsals are spool-shaped and all appear about the same as each other. The spinous processes jut out steeply from the centra, and feature sharp keels on the front and back sides. Unlike eutheriodonts, gorgonopsians do not have distinguished lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are, in human anatomy, the five vertebrae between the rib cage and the pelvis. They are the largest segments of the vertebral column and are characterized by the absence of the foramen transversarium within the transverse p ...

. Nonetheless, the dorsals equating to that series are similar to the lumbars of sabre-toothed cats with steeply oriented zygopophases, useful in stabilising the lower back especially when pinning down struggling prey.

There are three sacral vertebrae

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human body, human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the vertebral column, spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situ ...

, and the series attached to the pelvis

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

by the first vertebra. The pelvis is reptilian, with separated ilium, ischium

The ischium () form ...

, and pubis. The femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates ...

is slightly s-shaped, and is short but longer and slenderer than the humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a r ...

. For most, the tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it conn ...

and fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity ...

strongly curve into each other, and the tibia is more robust than the fibula. The joint between the ankle and the heel bones may have been somewhat mobile. The fifth digit for both the hands and feet was not attached to the carpus

In human anatomy, the wrist is variously defined as (1) the carpus or carpal bones, the complex of eight bones forming the proximal skeletal segment of the hand; "The wrist contains eight bones, roughly aligned in two rows, known as the carpal ...

/ tarsus, and instead connected directly to the ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

/heel bone.

Taxonomy

Fossil bearing sites

In 1876, the first gorgonopsian remains were identified in the

In 1876, the first gorgonopsian remains were identified in the Beaufort Group

The Beaufort Group is the third of the main subdivisions of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. It is composed of a lower Adelaide Subgroup and an upper Tarkastad Subgroup. It follows conformably after the Ecca Group and unconformably underli ...

of the Karoo Supergroup

The Karoo Supergroup is the most widespread stratigraphic unit in Africa south of the Kalahari Desert. The supergroup consists of a sequence of units, mostly of nonmarine origin, deposited between the Late Carboniferous and Early Jurassic, a peri ...

of South Africa, by the biologist and paleontologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

. He classified the fossils as '' Gorgonops torvus'', combining the Greek Gorgon

A Gorgon ( /ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ ''Gorgṓn/Gorgṓ'') is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the te ...

, a mythological beast, with the word (), meaning 'aspect'. In Africa, gorgonopsians have also been found in Karoo outcroppings in the Ruhuhu Valley of Tanzania, the Upper Luangwa Valley of Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

, and Chiweta, Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northe ...

.

Gorgonopsians were first identified in

Gorgonopsians were first identified in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

in the 1890s at the Sokolki locality on the Northern Dvina

The Northern Dvina (russian: Се́верная Двина́, ; kv, Вы́нва / Výnva) is a river in northern Russia flowing through the Vologda Oblast and Arkhangelsk Oblast into the Dvina Bay of the White Sea. Along with the Pechora River ...

in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

under the supervision of Russian palaeontologist Vladimir Prokhorovich Amalitskii

Vladimir Prokhorovich Amalitskii (russian: Владимир Прохорович Амалицкий; 1860–1917) (alternative spelling: Amalitzky) was a Russian paleontologist and professor at Warsaw University who was involved in the discovery a ...

. In a posthumous publication, it was described as ''Inostrancevia alexandri'', and it is one of the best known and largest gorgonopsians. Since then, only a few more Russian genera have been described: ''Pravoslavlevia

''Pravoslavlevia'' is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids that lived in the late Permian and is part of the Sokolki subcomplex of Russia. It had a skull long. The total length of the animal was about . Only one species (''P. parva'') is k ...

'', '' Viatkogorgon'', ''Suchogorgon

''Suchogorgon'' is an extinct genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above specie ...

'', '' Leogorgon'', and '' Nochnitsa''.

Gorgonopsians are conspicuously absent beyond these 2 areas. In 1979, Chinese palaeontologist Yang Zhongjian described a Chinese gorgonopsian "'' Wangwusaurus tayuensis''" based on teeth from the Late Permian Jiyuan Formation, but in 1981, palaeontologists Denise Sigogneau-Russell and Ai-Lin Sun found the assigned material to be a random assemblage of which only two have even a remote similarity to Gorgonopsia. In 2003, Indian palaeontologists Sanghamitra Ray and Saswati Bandyopadhyay assigned some skull fragments from the Late Permian Kundaram Formation to a medium-sized gorgonopsian, though the gorgonopsian characteristics have also been documented in some therocephalians. In 2008, a large and probably rubidgeine upper jaw fragment and canine was identified at the Late Permian Moradi Formation in Niger (one of the few low-latitude Late Permian tetrapod-bearing formations), and is the first evidence of a low-latitude gorgonopsian.

Classification

Upon discovery, Owen presumed that ''Gorgonops'' and several other taxa he described from the Karoo Supergroup were cold-blooded reptiles, despite bearing teeth resembling those of carnivorous mammals. He proposed classifying all of them under the newly coined

Upon discovery, Owen presumed that ''Gorgonops'' and several other taxa he described from the Karoo Supergroup were cold-blooded reptiles, despite bearing teeth resembling those of carnivorous mammals. He proposed classifying all of them under the newly coined order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

Theriodontia (which he placed in the class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

Reptilia). He decided to subdivide Theriodontia into families based on the anatomy of the nostrils (the bony narials)—"Mononarialia" for those with one opening in the skull for the nose as in mammals, "Binarialia" for those with two openings as in reptiles, and "Tectinarialia" for ''Gorgonops'' because its opening was overshadowed by a thick bone roof (''tectus'' is Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "covered, roofed, decked"). In 1890, English naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker ...

made ''Gorgonops'' the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

of the family Gorgonopsidae. British palaeontologist Harry Seeley in 1895 believed ''Gorgonops'' lacked an opening in the temporal bone (temporal fenestra), which is a diagnostic feature of Theriodontia, and so elevated Gorgonopsidae to Gorgonopsia, distinct from Theriodontia. He classified all South African materials bearing both reptilian and mammalian traits into the order "Theriosuchia", and considered Gorgonopsia and Theriodontia suborder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

s of it. American palaeontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

completely reworked the classification of Reptilia in 1903, and erected two major groups: Diapsida

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years ag ...

and Synapsida, and in 1905, South African palaeontologist Robert Broom

Robert Broom FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University of Glasgow.

From 1903 to 1910, he ...

created a third group, Therapsida, to house the "mammal-like reptiles", including Theriodontia. He also challenged Seeley's claim and relegated ''Gorgonops'' back to Theriodontia, but he placed it into his newly erected subgroup Therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct suborder of eutheriodont therapsids (mammals and their close relatives) from the Permian and Triassic. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of thei ...

, dissolving Gorgonopsia. In 1913, especially in light of an almost complete ''G. torvus'' skull discovered by the Reverend John H. Whaits, Broom reinstated Gorgonopsia.

The number of South African genera rapidly grew in the 20th-century, headed principally by Broom, whose extensive work on the Karoo therapsids—from the beginning of his career in the country in 1897 to his death in 1951—led to his description of 57 gorgonopsian holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

s and 29 genera. Many of Broom's taxa would later be invalidated. Many other contemporary workers created wholly new species or genera based on single specimens. Consequently, Gorgonopsia has been the subject of much taxonomic turmoil, and is one of the most problematic synapsid groups. Because the skull anatomy differs very little across taxa, many are defined based on vague proportional differences, including even the well-known members. Nominal species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

are distinguished predominantly by traits which are known to be quite variable depending on the age of the individual, including eye orbit size, snout length, and number of postcanine teeth. Thus, it is possible that some taxa are synonymous

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

with each other, and represent different stages of development.

Among the first attempts to organise the clade was carried out by British zoologist David Meredith Seares Watson and American palaeontologist

Among the first attempts to organise the clade was carried out by British zoologist David Meredith Seares Watson and American palaeontologist Alfred Romer

Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 – November 5, 1973) was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Biography

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of Harry Houston Romer an ...

in 1956, who split it into twenty families, of which the members of three (Burnetiidae, Hipposauridae, and Phthinosuchidae) are not considered gorgonopsians anymore. In 1970 and again in 1989, predominantly considering African taxa, Sigogneau-Russell published a comprehensive monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

on Gorgonopsia (defining it as an infraorder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

), and recognised only two families: Watongiidae and Gorgonopidae. ''Watongia

''Watongia'' is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsids from Middle Permian of Oklahoma. Only one species has been described, ''Watongia meieri'', from the Chickasha Formation. It was assigned to family Gorgonopsidae by OlsonOlson, E.C. 197 ...

'' was moved to Varanopidae

Varanopidae is an extinct family of amniotes that resembled monitor lizards and may have filled a similar niche, hence the name. Typically, they are considered synapsids that evolved from an '' Archaeothyris''-like synapsid in the Late Carbonife ...

in 2004. She split Gorgonopidae into three subfamilies—Gorgonopsinae, Rubidgeinae, and Inostranceviinae—and reduced the number of genera to twenty-three. In 2002, Russian palaeontologist Mikhail Feodosʹevich Ivakhnenko, considering the Russian taxa, instead considered Gorgonopsia a suborder, and grouped it together with Dinocephalia

Dinocephalians (terrible heads) are a clade of large-bodied early therapsids that flourished in the Early and Middle Permian between 279.5 and 260 million years ago (Ma), but became extinct during the Capitanian mass extinction event. Dinocephal ...

into the order "Gorgodontia". He divided Gorgonopsia into the superfamilies "Gorgonopioidea" (families Gorgonopidae, Cyonosauridae, and Galesuchidae) and "Rubidgeoidea" (Rubidgeidae, Phtinosuchidae, and Inostranceviidae). In 2007, biologist Eva V. I. Gebauer, in her comprehensive review of Gorgonopsia (her PhD dissertation), rejected Ivakhnenko's model in favour of Sigogneau-Russell's, and further reduced the number of genera to fourteen in addition to the Russian genera: ''Aloposaurus

''Aloposaurus'' is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It was first named by Robert Broom in 1910, and contains the type species ''A. gracilis'', and possibly a second species ''A. tenuis''. This sm ...

'', '' Cyonosaurus'', ''Aelurosaurus

''Aelurosaurus'' ("cat lizard", from Ancient Greek "cat" and "lizard") is a small, carnivorous, extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids from the Middle Permian to Late Permian of South Africa. It was discovered in the Karoo Basin of South Afr ...

'', ''Sauroctonus

''Sauroctonus'' (from el, σαῦρος , 'lizard' and el, κτόνος , 'murderer') is an extinct genus of therapsids.

''Sauroctonus progressus'' was a large (2 m long) gorgonopsid that lived in the Late Permian epoch before the Permian-T ...

'', ''Scylacognathus'', ''Eoarctops'', ''Gorgonops'', "''Dixeya''" ''nasuta (under the informal ''nomen nudum

In taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published with an adequate desc ...

'' "Njalila"), '' Lycaenops'', '' Arctognathus'', '' Aelurognathus'', '' Sycosaurus'', ''Clelandina

''Clelandina'' is an extinct genus of rubidgeine gorgonopsian from the Late Permian of ''Cistecephalus'' Assemblage Zone of South Africa. It was first named by Broom in 1948. The type and only species is ''C. rubidgei''. It is relatively ...

'', and ''Rubidgea''. In general, Sigogneau-Russell's model is supported, but there is little consensus on which genera can be assigned to which subfamilies. In 2015, American palaeontologist Christian F. Kammerer and colleagues redescribed '' Eriphostoma'' (which was labelled as an indeterminate theriodont) as a gorgonopsian, and sunk ''Scylacognathus'' and the next year ''Eoarctops'' into it.

The first phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological s ...

(family tree) of the members of Gorgonopsia was published in 2016 by American palaeontologist Christian F. Kammerer, who specifically investigated Rubidgeinae, and re-described both the subfamily and the nine species he assigned to it (reducing the number from thirty-six species). Kammerer also resurrected '' Dinogorgon'', '' Leontosaurus'', '' Ruhuhucerberus'', and '' Smilesaurus''. Kammerer was unsure if ''Leontosaurus'', ''Clelandina'', ''Dinogorgon'', and ''Rubidgea'' all represent the same taxon or not (for which ''Dinogorgon'' has priority), but he decided to classify all of them in the tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

Rubidgeini pending further examination. In 2018, Kammerer and Russian palaeontologist Vladimir Masyutin identified a new genus ''Nochnitsa'' as the basalmost known gorgonopsians, and found that all Russian taxa (except ''Viatkogorgon'', which is in the outclade) form a completely separate clade from the African taxa. Also in 2018, palaeobiologist Eva-Maria Bendel, Kammerer, and colleagues resurrected ''Cynariops

''Cynariops'' is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian that lived in what is now South Africa during the Permian. The holotype skull specimen MB.R.999 was made the basis of the new genus and species ''Cynariops robustus'' by Robert Broom in 1925, but ...

''. In 2022, Kammerer and fellow palaeontologist Bruce S. Rubidge described ''Phorcys

In Greek mythology, Phorcys or Phorcus (; grc, Φόρκυς) is a primordial sea god, generally cited (first in Hesiod) as the son of Pontus and Gaia (Earth). Classical scholar Karl Kerenyi conflated Phorcys with the similar sea gods Nereu ...

'' from South Africa.

Evolution

Synapsida has traditionally been split into the basal "Pelycosauria

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is no ...

" and the derived Therapsida. The former comprises cold-blooded creatures with a sprawling gait and presumably lower metabolism which evolved in the Upper Carboniferous. Through the middle to late 20th-century, American palaeontologist Everett C. Olson

Everett Claire Olson (November 6, 1910 – November 27, 1993) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, and geologist noted for his seminal research of origin and evolution of vertebrate animals.

Through his research studying terrestrial verte ...

investigated synapsid diversity in the Middle Permian San Angelo

San Angelo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Tom Green County, Texas, United States. Its location is in the Concho Valley, a region of West Texas between the Permian Basin to the northwest, Chihuahuan Desert to the southwest, Osage Pl ...

, Flowerpot

A flowerpot, planter, planterette or plant pot, is a container in which flowers and other plants are cultivated and displayed. Historically, and still to a significant extent today, they are made from plain terracotta with no ceramic glaze, w ...

, and Chickasha Formations in North America, and noted that pelycosaur diversity reduced from six to three in these formations, and that they coexisted with several fragmentary specimens which he interpreted as therapsids. He then suggested the adaptive shift from pelycosaur-grade to therapsid-grade took place during the Middle Permian ( Olson's Extinction); however, the classification of those "therapsids" and the age of the formations have since been challenged. Thus, the exact timing of the therapsid takeover is unclear, but the seven major therapsid groups (Biarmosuchia

Biarmosuchians are an extinct clade of non-mammalian synapsids from the Permian. They are the most basal group of the therapsids. All of them were moderately-sized, lightly-built carnivores, intermediate in form between basal sphenacodont " pelyc ...

, Dinocephalia

Dinocephalians (terrible heads) are a clade of large-bodied early therapsids that flourished in the Early and Middle Permian between 279.5 and 260 million years ago (Ma), but became extinct during the Capitanian mass extinction event. Dinocephal ...

, Anomodont

Anomodontia is an extinct group of non-mammalian therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods. By far the most speciose group are the dicynodonts, a clade of beaked, tusked herbivores.Chinsamy-Turan, A. (2011) ''Forerunners of Mammals: Ra ...

ia, Gorgonopsia, Therocephalia, and Cynodontia) had evolved by 265 million years ago during the Wordian. The oldest gorgonopsian specimen is a partial snout (genus undeterminable) from the '' Eodicynodon'' Assemblage Zone of the Karoo Basin, roughly dating to the Wordian. ''Phorcys'' from the lowermost end of Karoo's '' Tapinocephalus'' Assemblage Zone, roughly dating a little later to the Wordian/Capitian boundary, is the oldest identifiable gorgonopsian taxon.

The Permian progressively became dryer and dryer. In the Upper Carboniferous and Lower Permian, pelycosaurs seem to have clung to the everwet

The Permian progressively became dryer and dryer. In the Upper Carboniferous and Lower Permian, pelycosaurs seem to have clung to the everwet coal swamp

Coal forests were the vast swathes of wetlands that covered much of the Earth's tropical land areas during the late Carboniferous ( Pennsylvanian) and Permian times.Cleal, C. J. & Thomas, B. A. (2005). "Palaeozoic tropical rainforests and their e ...

habitats near the equator (fossils known within 10° of either side of the palaeoequator); beyond this to about 30° was an expansive desert which extended all the way to the coast, separating the swamps from the temperate regions. By the Middle Permian, the equatorial forests had switched to a seasonal wet/dry system, but the swamps were connected to the temperate zones via coastal passages along East Pangaea, allowing cross-continental migration from what is now South Africa to what is now Russia. Therapsids appear to have evolved in this seasonally humid/dry landscape, expanding even into the temperate zones. At this point, synapsids were the only large terrestrial animals of their environment; and pelycosaurs may not have been able to adapt to the aridification. At about the time of pelycosaur extinction, therapsids experienced a major adaptive radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

(all carnivores) continuing into the Upper Permian.

Throughout the Middle Permian, the often gigantic dinocephalians were the dominant animals of their ecosystems. They disappear from the fossil record during the Capitanian mass extinction event

The Capitanian mass extinction event, also known as the end-Guadalupian extinction event or the pre-Lopingian crisis was an extinction event that predated the end-Permian extinction event and occurred around 260 million years ago during a period ...

caused by volcanic activity which has formed the Chinese Emeishan Traps

The Emeishan Traps constitute a flood basalt volcanic province, or large igneous province, in south-western China, centred in Sichuan province. It is sometimes referred to as the Permian Emeishan Large Igneous Province or Emeishan Flood Basalts. Li ...

. The exact cause of their extinction is unclear, but they were replaced by gorgonopsians and dicynodont

Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivorous animals with a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, typic ...

s (which began to greatly increase in size) and the smaller therocephalians. The rubidgeans were the most derived gorgonopsians, and consequently the most massive and heavily built.

Palaeobiology

Bite

Gorgonopsians were likely active predators. The rubidgeines have an especially robust skull among gorgonopsians, comparable to those of enormous macropredators which use their skulls as their primary weapon, such as

Gorgonopsians were likely active predators. The rubidgeines have an especially robust skull among gorgonopsians, comparable to those of enormous macropredators which use their skulls as their primary weapon, such as mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on ...

s or some theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaurs. Less robust gorgonopsians with longer canines and much weaker bite, such as ''Smilesaurus'' or ''Inostrancevia'', instead probably used their canines for slashing, much more similar to sabre-toothed cats. The postcanines of ''Clelandina'' were replaced by a smooth ridge unlike dicynodonts which have a blade-like keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail ...

ous ridge, and it may have predominantly gone after prey it could swallow whole. Gorgonopsian taxa did coexist with each other—as many as seven at one time–and the fact that some rubidgeines possess postcanines while some other contemporary ones do not suggests that they practiced niche partitioning

In ecology, niche differentiation (also known as niche segregation, niche separation and niche partitioning) refers to the process by which competing species use the environment differently in a way that helps them to coexist. The competitive exclu ...

and pursued different prey items.

The elongated canines have generally been thought to have been instrumental in their hunting tactics. The gorgonopsian jaw hinge was double jointed and made up of somewhat mobile and rotatable bones, which would have allowed them to open their mouths incredibly wide–perhaps in excess of 90°–without having to unhinge the jaw. It has alternatively been suggested (first in 2002 by biologists Blaire Van Valkenburgh and Tyson Secco, though in reference to cats) that sabres evolved primarily due to sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex (in ...

as a form of mating display. This is exhibited in some modern deer species, but is difficult to test given the lack of living sabre-toothed synapsid predators. In sabre-toothed cats, long-sabred ("dirk-toothed") taxa are thought to have been pursuit hunters, whereas short-toothed ("scimitar-toothed") taxa are thought to have been ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture or trap prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey ...

s. Among the dirk-toothed cats, these predators are suggested to have killed with a well-placed slash to the throat after grappling prey, but gorgonopsians may have been less precise with bite placement, armed with reptilian jaws and tooth arrangements. Instead, gorgonopsians possibly used a bite-and-retreat tactic: the predator would ambush its quarry and take a sizable and debilitating bite out of it, and then follow as the prey tried to escape before succumbing to its injury, whereupon the gorgonopsian would deliver a killing bite. Because the postcanines are reduced or entirely absent, meat would have been forcibly torn away from the carcass and swallowed whole. This "puncture–pull" strategy is also hypothesised to have been used by theropod dinosaurs.

Gorgonopsians, along with other early carnivores as well as crocodiles, predominantly relied on "Kinetic-Inertial system" (KI) of biting down onto prey, in which the pterygoid and

Gorgonopsians, along with other early carnivores as well as crocodiles, predominantly relied on "Kinetic-Inertial system" (KI) of biting down onto prey, in which the pterygoid and temporalis muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomati ...

s rapidly clamped the jaws shut, using momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass ...

and the kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its acce ...

of the jaws and teeth to grapple the victim. Mammalian carnivores, including sabre-toothed cats, instead rely mainly on the "Static-Pressure system" (SP) where the temporalis and masseter muscle

In human anatomy, the masseter is one of the muscles of mastication. Found only in mammals, it is particularly powerful in herbivores to facilitate chewing of plant matter. The most obvious muscle of mastication is the masseter muscle, since it ...

s produce a strong bite force to kill prey. The temporalis and masseter had only separated in mammals, and gorgonopsians instead had a muscle stretching from the underside of the skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In compar ...

, back to the squamosal bone The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral c ...

(at the back of the skull), and across the cheekbones. The part anchored by the cheeks stabilised the jawbone and allowed it to move side-to-side while closing. This may have been very important in biting, as the cheekbones get stronger in tandem with the canines getting longer.

Smaller gorgonopsians, such as ''Cyonosaurus'' (which may actually represent a juvenile of a different species), had gracile skulls and sabres, and may have acted much like jackal

Jackals are medium-sized canids native to Africa and Eurasia. While the word "jackal" has historically been used for many canines of the subtribe canina, in modern use it most commonly refers to three species: the closely related black-backed ...

s and foxes. Bigger gorgonopsians, such as ''Gorgonops'', had long robust snouts with strongly flared cheeks, which would have supported strong pterygoids and a powerful KI bite. The medium-size ''Arctognathus'' had a box-like skull and resultantly powerful snout, which would have allowed strong bending and torsion movements, and a combination of both KI and SP bite elements. Even bigger gorgonopsians, such as ''Arctops'', had a shorter and more convex snout like the earlier sphenecodont ''Dimetrodon

''Dimetrodon'' ( or ,) meaning "two measures of teeth,” is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsid that lived during the Cisuralian (Early Permian), around 295–272 million years ago (Mya). It is a member of the family Sphenacodont ...

'', and would have been able to rapidly clamp the jaws shut from a wide gape (which would have been necessary given the long canines). The even larger Rubidgeinae had extremely powerful, heavily built, buttressed skulls, with wide snouts, strongly flanged cheeks, and exceedingly long teeth; the sabres of ''Rubidgea atrox'' are longer than the teeth of ''Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosa ...

''.

Unlike mammalian carnivores, gorgonopsians (and therocephalians) had reduced or completely lacked postcanines, and the jaw likely could not exert shearing pressure necessary for crushing bones open to access the bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid biological tissue, tissue found within the Spongy bone, spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It i ...

. It has largely been unclear if bone marrow had even evolved yet in Permian synapsids (fish and many amphibians lack this in present day), but in 2021 it was shown that the Early Permian amphibians '' Seymouria'' and ''Discosauriscus

''Discosauriscus'' was a small seymouriamorph which lived in what is now Central and Western Europe in the Early Permian Period. Its best fossils have been found in the Broumov and Bačov Formations of Boskovice Furrow, in the Czech Republic. ...

'' likely had haematopoietic (red-blood-cell-producing) bone marrow in their limbs.

Locomotion

Gorgonopsians are considered to have been strictly terrestrial. They are thought to have been able to move with an erect gait similar to that used by crocodilians, the limbs positioned almost vertically as opposed to horizontally as in the sprawling gait of lizards. The glenoid cavity on the shoulder blade is strongly angled tailwards, so the limbs had limited forward movement, and they may have had a short stride length. Lizards often move their spines side to side to increase stride length, but the more vertically orientated

Gorgonopsians are considered to have been strictly terrestrial. They are thought to have been able to move with an erect gait similar to that used by crocodilians, the limbs positioned almost vertically as opposed to horizontally as in the sprawling gait of lizards. The glenoid cavity on the shoulder blade is strongly angled tailwards, so the limbs had limited forward movement, and they may have had a short stride length. Lizards often move their spines side to side to increase stride length, but the more vertically orientated facet joint

The facet joints (or zygapophysial joints, zygapophyseal, apophyseal, or Z-joints) are a set of synovial, plane joints between the articular processes of two adjacent vertebrae. There are two facet joints in each spinal motion segment and e ...

s connecting the vertebrae in gorgonopsians would have made the spine more rigid and stable, encumbering such movement.

The gorgonopsian shoulder joint has a highly unusual configuration. The humeral head which connects to the shoulder is longer than the glenoid, so it could not fit into the cavity. Consequently, they may have been attached with a large mass of cartilage, with the humerus performing a rolling movement over the glenoid. This could theoretically make the angle between the humerus and the glenoid anywhere from 80 to 145° when facing the animal. If the angle was on the lower end, this would have been a rather firm joint, allowing the deltoids to exert great force through the forelimb, such as when pinning down struggling prey, or holding down a carcass while ripping off flesh. If the humerus was positioned at a higher angle, this could have permitted enhanced extension forwards and backwards (along the long axis) and thus greater stride length, useful in an attack or short chases. The shoulder blade expands off to the sides of the animal (protrudes laterally), also providing a large attachment for the deltoids. All the scapulohumeral muscles had strongly developed attachments, particularly the deltoids. When extending the forelimbs, the deltoids may have raised the front side (anterior margin) of the humerus, and coracobrachialis muscle

The coracobrachialis muscle is the smallest of the three muscles that attach to the coracoid process of the scapula. (The other two muscles are pectoralis minor and the short head of the biceps brachii.) It is situated at the upper and medial part ...

lowered the back side (posterior margin). When retracting the forelimb, the pectoralis muscle

Pectoral muscles (colloquially referred to as "pecs") are the muscles that connect the front of the human chest with the bones of the upper arm and shoulder. This region contains four muscles that provide movements to the upper limbs or ribs.

Pe ...

may have pushed the anterior margin down, and the subscapularis muscle

The subscapularis is a large triangular muscle which fills the subscapular fossa and inserts into the lesser tubercle of the humerus and the front of the capsule of the shoulder-joint.

Structure

It arises from its medial two-thirds and

So ...

pulled the posterior margin up.

The pelvis joint has the usual ball-and-socket joint