Gondwanaland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gondwana () was a large

Gondwana () was a large

The continent of Gondwana was named by the Austrian scientist

The continent of Gondwana was named by the Austrian scientist

The assembly of Gondwana was a protracted process during the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic, which remains incompletely understood because of the lack of paleo-magnetic data. Several orogenies, collectively known as the

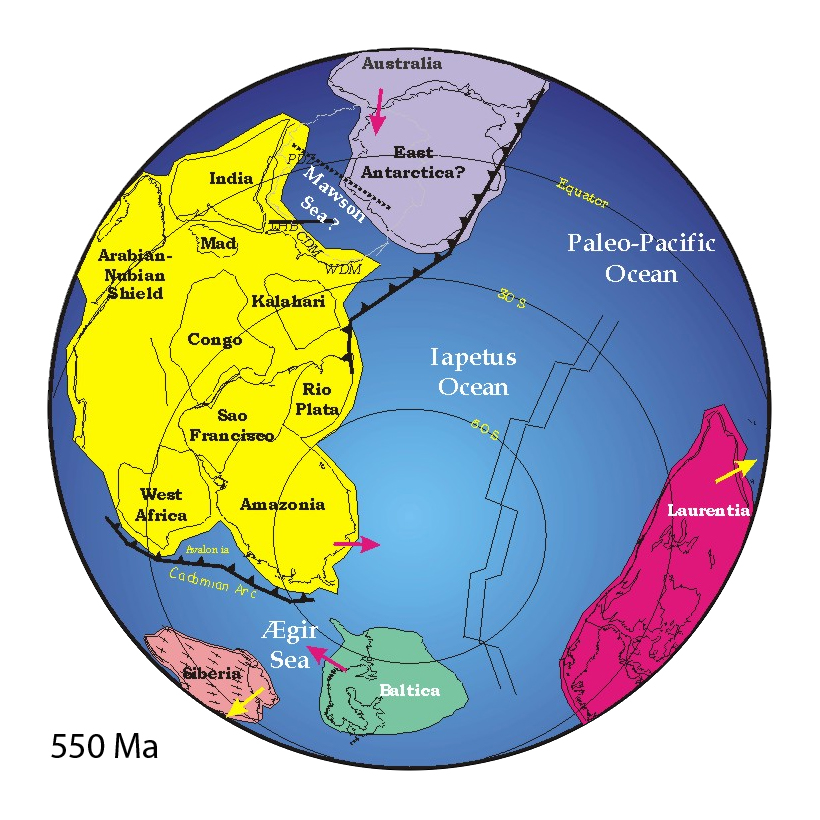

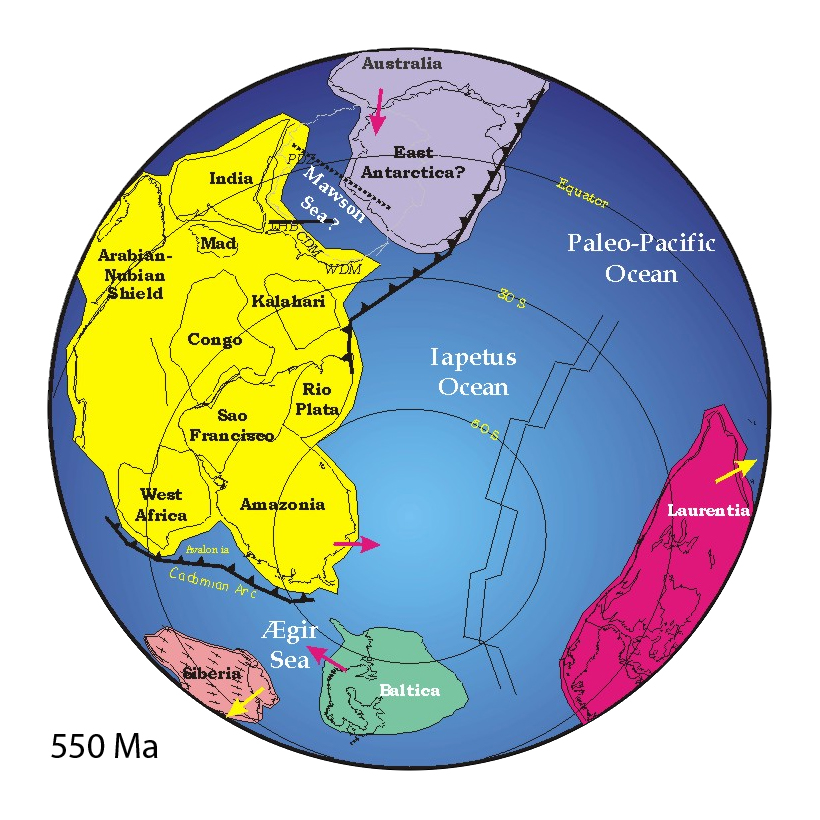

The assembly of Gondwana was a protracted process during the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic, which remains incompletely understood because of the lack of paleo-magnetic data. Several orogenies, collectively known as the  The continent Australia/ Mawson was still separated from India, eastern Africa, and Kalahari by , when most of western Gondwana had already been amalgamated. By 550 Ma, India had reached its Gondwanan position, which initiated the Kuunga orogeny (also known as the Pinjarra orogeny). Meanwhile, on the other side of the newly forming Africa, Kalahari collided with Congo and Rio de la Plata which closed the Adamastor Ocean. 540–530 Ma, the closure of the Mozambique Ocean brought India next to Australia–East Antarctica, and both North and South China were in proximity to Australia.

As the rest of Gondwana formed, a complex series of orogenic events assembled the eastern parts of Gondwana (eastern Africa, Arabian-Nubian Shield, Seychelles, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, East Antarctica, and Australia) . First the Arabian-Nubian Shield collided with eastern Africa (in the Kenya-Tanzania region) in the East African Orogeny . Then Australia and East Antarctica were merged with the remaining Gondwana in the Kuunga Orogeny.

The later Malagasy orogeny at about 550–515 Mya affected Madagascar, eastern East Africa and southern India. In it, Neoproterozoic India collided with the already combined Azania and Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block, suturing along the Mozambique Belt.

The Terra Australis Orogen developed along Gondwana's western, southern, and eastern margins. Proto-Gondwanan Cambrian arc belts from this margin have been found in eastern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, and Antarctica. Though these belts formed a continuous arc chain, the direction of subduction was different between the Australian-Tasmanian and New Zealand-Antarctica arc segments.

The continent Australia/ Mawson was still separated from India, eastern Africa, and Kalahari by , when most of western Gondwana had already been amalgamated. By 550 Ma, India had reached its Gondwanan position, which initiated the Kuunga orogeny (also known as the Pinjarra orogeny). Meanwhile, on the other side of the newly forming Africa, Kalahari collided with Congo and Rio de la Plata which closed the Adamastor Ocean. 540–530 Ma, the closure of the Mozambique Ocean brought India next to Australia–East Antarctica, and both North and South China were in proximity to Australia.

As the rest of Gondwana formed, a complex series of orogenic events assembled the eastern parts of Gondwana (eastern Africa, Arabian-Nubian Shield, Seychelles, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, East Antarctica, and Australia) . First the Arabian-Nubian Shield collided with eastern Africa (in the Kenya-Tanzania region) in the East African Orogeny . Then Australia and East Antarctica were merged with the remaining Gondwana in the Kuunga Orogeny.

The later Malagasy orogeny at about 550–515 Mya affected Madagascar, eastern East Africa and southern India. In it, Neoproterozoic India collided with the already combined Azania and Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block, suturing along the Mozambique Belt.

The Terra Australis Orogen developed along Gondwana's western, southern, and eastern margins. Proto-Gondwanan Cambrian arc belts from this margin have been found in eastern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, and Antarctica. Though these belts formed a continuous arc chain, the direction of subduction was different between the Australian-Tasmanian and New Zealand-Antarctica arc segments.

Gondwana and

Gondwana and

The adjective "Gondwanan" is in common use in

The adjective "Gondwanan" is in common use in

The

The

Graphical subjects dealing with Tectonics and Paleontology

The Gondwana Map Project

* {{Authority control Historical continents Former supercontinents Biogeography Paleozoic paleogeography Mesozoic paleogeography Geology of Africa Geology of Antarctica Geology of Asia Geology of India Geology of Australia Geology of South America Prehistory of Antarctica Paleozoic Africa Paleozoic Antarctica Paleozoic Asia Paleozoic South America Mesozoic Africa Mesozoic Antarctica Mesozoic Asia Mesozoic South America

Gondwana () was a large

Gondwana () was a large landmass

A landmass, or land mass, is a large region or area of land. The term is often used to refer to lands surrounded by an ocean or sea, such as a continent or a large island. In the field of geology, a landmass is a defined section of contine ...

, often referred to as a supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is pre ...

(about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

(about 180 million years ago). The final stages of break-up, involving the separation of Antarctica from South America (forming the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

) and Australia, occurred during the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

. Gondwana was not considered a supercontinent by the earliest definition, since the landmasses of Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, is mo ...

, Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, although ...

, and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part o ...

were separated from it. To differentiate it from the Indian region of the same name (see ), it is also commonly called Gondwanaland.

Gondwana was formed by the accretion

Accretion may refer to:

Science

* Accretion (astrophysics), the formation of planets and other bodies by collection of material through gravity

* Accretion (meteorology), the process by which water vapor in clouds forms water droplets around nucl ...

of several craton

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and ...

s. Eventually, Gondwana became the largest piece of continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as continental shelves. This layer is sometimes called ''sial'' bec ...

of the Palaeozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ''z ...

Era, covering an area of about , about one-fifth of the Earth's surface. During the Carboniferous Period

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferous ...

, it merged with Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

to form a larger supercontinent called Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

. Gondwana (and Pangaea) gradually broke up during the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

Era. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, Australia, Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as ( Māori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83–79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L. ...

, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

, and the Indian Subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, Ind ...

.

The formation of Gondwana began with the East African Orogeny

The East African Orogeny (EAO) is the main stage in the Neoproterozoic assembly of East and West Gondwana (Australia–India–Antarctica and Africa–South America) along the Mozambique Belt.

Gondwana assembly

The notion that Gondwana was assem ...

, the collision of India and Madagascar with East Africa, and was completed with the overlapping Brasiliano and Kuunga orogenies, the collision of South America with Africa, and the addition of Australia and Antarctica, respectively.

Regions that were part of Gondwana shared floral and zoological elements that persist to the present day.

Name

The continent of Gondwana was named by the Austrian scientist

The continent of Gondwana was named by the Austrian scientist Eduard Suess

Eduard Suess (; 20 August 1831 - 26 April 1914) was an Austrian geologist and an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana (proposed in 1861) and ...

, after the region in central India of the same name, which is derived from Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the la ...

for "forest of the Gonds

The Gondi (Gōndi) or Gond or Koitur are a Dravidian ethno-linguistic group. They are one of the largest tribal groups in India. They are spread over the states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Telangana, Andhra Prad ...

". The name had been previously used in a geological context, first by H.B. Medlicott in 1872, from which the Gondwana sedimentary sequences (Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

-Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

) are also described.

Some scientists prefer the term "Gondwanaland" to make a clear distinction between the region and the supercontinent.

Formation

The assembly of Gondwana was a protracted process during the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic, which remains incompletely understood because of the lack of paleo-magnetic data. Several orogenies, collectively known as the

The assembly of Gondwana was a protracted process during the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic, which remains incompletely understood because of the lack of paleo-magnetic data. Several orogenies, collectively known as the Pan-African orogeny

The Pan-African orogeny was a series of major Neoproterozoic orogenic events which related to the formation of the supercontinents Gondwana and Pannotia about 600 million years ago. This orogeny is also known as the Pan-Gondwanan or Saldanian Oro ...

, caused the continental fragments of a much older supercontinent, Rodinia

Rodinia (from the Russian родина, ''rodina'', meaning "motherland, birthplace") was a Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic supercontinent that assembled 1.26–0.90 billion years ago and broke up 750–633 million years ago.

were probabl ...

, to amalgamate. One of those orogenic belts, the Mozambique Belt

The Mozambique Belt is a band in the earth's crust that extends from East Antarctica through East Africa up to the Arabian-Nubian Shield. It formed as a suture between plates during the Pan-African orogeny, when Gondwana was formed.

The Mozam ...

, formed and was originally interpreted as the suture between East (India, Madagascar, Antarctica, and Australia) and West Gondwana (Africa and South America). Three orogenies were recognised during the 1990s: the East African Orogeny

The East African Orogeny (EAO) is the main stage in the Neoproterozoic assembly of East and West Gondwana (Australia–India–Antarctica and Africa–South America) along the Mozambique Belt.

Gondwana assembly

The notion that Gondwana was assem ...

() and Kuunga orogeny (including the Malagasy Orogeny in southern Madagascar) (), the collision between East Gondwana and East Africa in two steps, and the Brasiliano orogeny

Brasiliano orogeny or Brasiliano cycle ( pt, Orogênese Brasiliana and ''Ciclo Brasiliano'') refers to a series of orogenies of Neoproterozoic age exposed chiefly in Brazil but also in other parts of South America. The Brasiliano orogeny is a re ...

(), the successive collision between South American and African craton

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and ...

s.

The last stages of Gondwanan assembly overlapped with the opening of the Iapetus Ocean

The Iapetus Ocean (; ) was an ocean that existed in the late Neoproterozoic and early Paleozoic eras of the geologic timescale (between 600 and 400 million years ago). The Iapetus Ocean was situated in the southern hemisphere, between the paleoco ...

between Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, although ...

and western Gondwana. During this interval, the Cambrian explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

occurred. Laurentia was docked against the western shores of a united Gondwana for a brief period near the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary, forming the short-lived and still disputed supercontinent Pannotia

Pannotia (from Greek: '' pan-'', "all", '' -nótos'', "south"; meaning "all southern land"), also known as the Vendian supercontinent, Greater Gondwana, and the Pan-African supercontinent, was a relatively short-lived Neoproterozoic supercontinent ...

.

The Mozambique Ocean

The Mozambique Belt is a band in the earth's crust that extends from East Antarctica through East Africa up to the Arabian-Nubian Shield. It formed as a suture between plates during the Pan-African orogeny, when Gondwana was formed.

The Mozamb ...

separated the Congo–Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands an ...

– Bangweulu Block of central Africa from Neoproterozoic India (India, the Antongil

''Helodranon' Antongila'' (Bay of Antongila), more commonly called Antongil Bay in English, is the largest bay in Madagascar. This bay is on the island's east coast, toward the northern end of the eastern coastline of the island. It is within Anal ...

Block in far eastern Madagascar, the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

, and the Napier and Rayner Complexes in East Antarctica

East Antarctica, also called Greater Antarctica, constitutes the majority (two-thirds) of the Antarctic continent, lying on the Indian Ocean side of the continent, separated from West Antarctica by the Transantarctic Mountains. It lies almost ...

). The Azania

Azania ( grc, Ἀζανία) is a name that has been applied to various parts of southeastern tropical Africa. In the Roman period and perhaps earlier, the toponym referred to a portion of the Southeast Africa coast extending from northern Kenya ...

continent (much of central Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

, the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

and parts of Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and s ...

and Arabia) was an island in the Mozambique Ocean.

The continent Australia/ Mawson was still separated from India, eastern Africa, and Kalahari by , when most of western Gondwana had already been amalgamated. By 550 Ma, India had reached its Gondwanan position, which initiated the Kuunga orogeny (also known as the Pinjarra orogeny). Meanwhile, on the other side of the newly forming Africa, Kalahari collided with Congo and Rio de la Plata which closed the Adamastor Ocean. 540–530 Ma, the closure of the Mozambique Ocean brought India next to Australia–East Antarctica, and both North and South China were in proximity to Australia.

As the rest of Gondwana formed, a complex series of orogenic events assembled the eastern parts of Gondwana (eastern Africa, Arabian-Nubian Shield, Seychelles, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, East Antarctica, and Australia) . First the Arabian-Nubian Shield collided with eastern Africa (in the Kenya-Tanzania region) in the East African Orogeny . Then Australia and East Antarctica were merged with the remaining Gondwana in the Kuunga Orogeny.

The later Malagasy orogeny at about 550–515 Mya affected Madagascar, eastern East Africa and southern India. In it, Neoproterozoic India collided with the already combined Azania and Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block, suturing along the Mozambique Belt.

The Terra Australis Orogen developed along Gondwana's western, southern, and eastern margins. Proto-Gondwanan Cambrian arc belts from this margin have been found in eastern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, and Antarctica. Though these belts formed a continuous arc chain, the direction of subduction was different between the Australian-Tasmanian and New Zealand-Antarctica arc segments.

The continent Australia/ Mawson was still separated from India, eastern Africa, and Kalahari by , when most of western Gondwana had already been amalgamated. By 550 Ma, India had reached its Gondwanan position, which initiated the Kuunga orogeny (also known as the Pinjarra orogeny). Meanwhile, on the other side of the newly forming Africa, Kalahari collided with Congo and Rio de la Plata which closed the Adamastor Ocean. 540–530 Ma, the closure of the Mozambique Ocean brought India next to Australia–East Antarctica, and both North and South China were in proximity to Australia.

As the rest of Gondwana formed, a complex series of orogenic events assembled the eastern parts of Gondwana (eastern Africa, Arabian-Nubian Shield, Seychelles, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, East Antarctica, and Australia) . First the Arabian-Nubian Shield collided with eastern Africa (in the Kenya-Tanzania region) in the East African Orogeny . Then Australia and East Antarctica were merged with the remaining Gondwana in the Kuunga Orogeny.

The later Malagasy orogeny at about 550–515 Mya affected Madagascar, eastern East Africa and southern India. In it, Neoproterozoic India collided with the already combined Azania and Congo–Tanzania–Bangweulu Block, suturing along the Mozambique Belt.

The Terra Australis Orogen developed along Gondwana's western, southern, and eastern margins. Proto-Gondwanan Cambrian arc belts from this margin have been found in eastern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, and Antarctica. Though these belts formed a continuous arc chain, the direction of subduction was different between the Australian-Tasmanian and New Zealand-Antarctica arc segments.

Peri-Gondwana development: Paleozoic rifts and accretions

Many terranes were accreted to Eurasia during Gondwana's existence, but the Cambrian or Precambrian origin of many of these terranes remains uncertain. For example, some Palaeozoic terranes and microcontinents that now make up Central Asia, often called the "Kazakh" and "Mongolian terranes", were progressively amalgamated into the continent Kazakhstania in the Late Silurian. Whether these blocks originated on the shores of Gondwana is not known. In the Early Palaeozoic, theArmorican terrane

The Armorican terrane, Armorican terrane assemblage, or simply Armorica, was a microcontinent or group of continental fragments that rifted away from Gondwana towards the end of the Silurian and collided with Laurussia towards the end of the Car ...

, which today form large parts of France, was part of either Peri-Gondwana or core Gondwana; the Rheic Ocean closed in front of it and the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean opened behind it. Precambrian rocks from the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

suggest that it, too, formed part of core Gondwana before its detachment as an orocline

An orocline — from the Greek words for "mountain" and "to bend" — is a bend or curvature of an orogenic (mountain building) belt imposed after it was formed. The term was introduced by S. Warren Carey in 1955 in a paper setting forth how comp ...

in the Variscan orogeny

The Variscan or Hercynian orogeny was a geologic mountain-building event caused by Late Paleozoic continental collision between Euramerica (Laurussia) and Gondwana to form the supercontinent of Pangaea.

Nomenclature

The name ''Variscan'', comes f ...

close to the Carboniferous–Permian boundary.

South-east Asia was made of Gondwanan and Cathaysia

Cathaysia was a microcontinent or a group of terranes that rifted off Gondwana during the Late Paleozoic. They mostly correspond to modern territory of China, which were split into the North China and South China blocks.

Terminology

The terms " ...

n continental fragments that were assembled during the Mid-Palaeozoic and Cenozoic. This process can be divided into three phases of rifting along Gondwana's northern margin: first, in the Devonian, North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

and South China

South China () is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is that most of its citizens are not n ...

, together with Tarim and Quidam

''Quidam'' ( ) was the ninth stage show produced by Cirque du Soleil. It premiered in April 1996 and has been watched by millions of spectators around the world. ''Quidam'' originated as a big-top show in Montreal and was converted into an arena ...

(north-western China) rifted, opening the Palaeo-Tethys behind them. These terranes accreted to Asia during Late Devonian and Permian. Second, in the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian, Cimmerian terranes opened Meso-Tethys Ocean; Sibumasu and Qiangtang were added to south-east Asia during Late Permian

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effect, ...

and Early Jurassic. Third, in the Late Triassic to Late Jurassic, Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhasa ...

, West Burma, Woyla terranes opened the Neo-Tethys Ocean; Lhasa collided with Asia during the Early Cretaceous, and West Burma and Woyla during the Late Cretaceous.

Gondwana's long, northern margin remained a mostly passive margin throughout the Palaeozoic. The Early Permian opening of the Neo-Tethys Ocean along this margin produced a long series of terranes, many of which were and still are being deformed in the Himalaya Orogeny. These terranes are, from Turkey to north-eastern India: the Taurides in southern Turkey; the Lesser Caucasus Terrane in Georgia; the Sanand, Alborz, and Lut terranes in Iran; the Mangysglak or Kopetdag Terrane in the Caspian Sea; the Afghan Terrane; the Karakorum Terrane in northern Pakistan; and the Lhasa and Qiangtang terranes in Tibet. The Permian–Triassic widening of the Neo-Tethys pushed all these terranes across the Equator and over to Eurasia.

Southwestern accretions

During the Neoproterozoic to Palaeozoic phase of the Terra Australis Orogen, a series of terranes were rafted from the proto-Andean margin when the Iapteus Ocean opened, to be added back to Gondwana during the closure of that ocean. During the Paleozoic, some blocks which helped to form parts of theSouthern Cone

The Southern Cone ( es, Cono Sur, pt, Cone Sul) is a geographical and cultural subregion composed of the southernmost areas of South America, mostly south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Traditionally, it covers Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, bou ...

of South America, include a piece transferred from Laurentia when the west edge of Gondwana scraped against southeast Laurentia in the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

The ...

. This is the Cuyania or Precordillera terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its own ...

of the Famatinian orogeny in northwest Argentina which may have continued the line of the Appalachians

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

southwards. Chilenia terrane accreted later against Cuyania. The collision of the Patagonian terrane with the southwestern Gondwanan occurred in the late Paleozoic. Subduction-related igneous rocks from beneath the North Patagonian Massif have been dated at 320–330 million years old, indicating that the subduction process initiated in the early Carboniferous. This was relatively short lived (lasting about 20 million years), and initial contact of the two landmasses occurred in the mid-Carboniferous, with broader collision during the early Permian. In the Devonian, an island arc

Island arcs are long chains of active volcanoes with intense seismic activity found along convergent tectonic plate boundaries. Most island arcs originate on oceanic crust and have resulted from the descent of the lithosphere into the mantle alo ...

named Chaitenia accreted to Patagonia in what is now south-central Chile.

Gondwana as part of Pangaea: Late Paleozoic to Early Mesozoic

Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

formed the Pangaea supercontinent during the Carboniferous. Pangaea began to break up in the Mid-Jurassic when the Central Atlantic opened.

In the western end of Pangaea, the collision between Gondwana and Laurasia closed the Rheic and Palaeo-Tethys oceans. The obliquity of this closure resulted in the docking of some northern terranes in the Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of , usually run as a road running, road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There are also w ...

, Ouachita, Alleghanian, and Variscan

The Variscan or Hercynian orogeny was a geologic mountain-building event caused by Late Paleozoic continental collision between Euramerica (Laurussia) and Gondwana to form the supercontinent of Pangaea.

Nomenclature

The name ''Variscan'', come ...

orogenies, respectively. Southern terranes, such as Chortis and Oaxaca, on the other hand, remained largely unaffected by the collision along the southern shores of Laurentia. Some Peri-Gondwanan terranes, such as Yucatán

Yucatán (, also , , ; yua, Yúukatan ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán,; yua, link=no, Xóot' Noj Lu'umil Yúukatan. is one of the 31 states which comprise the federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate mun ...

and Florida

Florida is a U.S. state, state located in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia (U.S. state), Geo ...

, were buffered from collisions by major promontories. Other terranes, such as Carolina and Meguma, were directly involved in the collision. The final collision resulted in the Variscan-Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a mountain range, system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovicia ...

, stretching from present-day Mexico to southern Europe. Meanwhile, Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, is mo ...

collided with Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part o ...

and Kazakhstania which resulted in the Uralian orogeny

The Uralian orogeny refers to the long series of linear deformation and mountain building events that raised the Ural Mountains, starting in the Late Carboniferous and Permian periods of the Palaeozoic Era, 323–299 and 299–251 million years a ...

and Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

. Pangaea was finally amalgamated in the Late Carboniferous-Early Permian, but the oblique forces continued until Pangaea began to rift in the Triassic.

In the eastern end, collisions occurred slightly later. The North China

North China, or Huabei () is a geographical region of China, consisting of the provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Part of the larger region of Northern China (''Beifang''), it lies north of the Qinling–Huai ...

, South China

South China () is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is that most of its citizens are not n ...

, and Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

blocks rifted from Gondwana during the middle Paleozoic and opened the Proto-Tethys Ocean. North China docked with Mongolia and Siberia during the Carboniferous–Permian, followed by South China. The Cimmerian

The Cimmerians ( Akkadian: , romanized: ; Hebrew: , romanized: ; Ancient Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West ...

blocks then rifted from Gondwana to form the Palaeo-Thethys and Neo-Tethys oceans in the Late Carboniferous, and docked with Asia during the Triassic and Jurassic. Western Pangaea began to rift while the eastern end was still being assembled.

The formation of Pangaea and its mountains had a tremendous impact on global climate and sea levels, which resulted in glaciations and continent-wide sedimentation. In North America, the base of the Absaroka sequence coincides with the Alleghanian and Ouachita orogenies and are indicative of a large-scale change in the mode of deposition far away from the Pangaean orogenies. Ultimately, these changes contributed to the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, as ...

and left large deposits of hydrocarbons, coal, evaporite, and metals.

The break-up of Pangaea began with the Central Atlantic magmatic province

The Central Atlantic magmatic province (CAMP) is the Earth's largest continental large igneous province, covering an area of roughly 11 million km2. It is composed mainly of basalt that formed before Pangaea broke up in the Mesozoic Era, near the ...

(CAMP) between South America, Africa, North America, and Europe. CAMP covered more than seven million square kilometres over a few million years, reached its peak at , and coincided with the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event

The Triassic–Jurassic (Tr-J) extinction event, often called the end-Triassic extinction, marks the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, , and is one of the top five major extinction events of the Phanerozoic eon, profoundly affec ...

. The reformed Gondwanan continent was not precisely the same as that which had existed before Pangaea formed; for example, most of Florida

Florida is a U.S. state, state located in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia (U.S. state), Geo ...

and southern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,76 ...

is underlain by rocks that were originally part of Gondwana, but this region stayed attached to North America when the Central Atlantic opened.

Break-up

Mesozoic

Antarctica, the centre of the supercontinent, shared boundaries with all other Gondwana continents and the fragmentation of Gondwana propagated clockwise around it. The break-up was the result of the eruption of the Karoo-Ferrar igneous province, one of the Earth's most extensivelarge igneous province

A large igneous province (LIP) is an extremely large accumulation of igneous rocks, including intrusive (sills, dikes) and extrusive (lava flows, tephra deposits), arising when magma travels through the crust towards the surface. The formation ...

s (LIP) , but the oldest magnetic anomalies between South America, Africa, and Antarctica are found in what is now the southern Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Marth ...

where initial break-up occurred during the Jurassic .

Opening of western Indian Ocean

Gondwana began to break up in the early Jurassic following the extensive and fast emplacement of theKaroo-Ferrar

The Karoo and Ferrar Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs) are two large igneous provinces in Southern Africa and Antarctica respectively, collectively known as the Karoo-Ferrar, Gondwana,E.g. or Southeast African LIP, associated with the initial break-u ...

flood basalt

A flood basalt (or plateau basalt) is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot reach ...

s . Before the Karoo plume initiated rifting between Africa and Antarctica, it separated a series of smaller continental blocks from Gondwana's southern, Proto-Pacific margin (along what is now the Transantarctic Mountains

The Transantarctic Mountains (abbreviated TAM) comprise a mountain range of uplifted (primarily sedimentary) rock in Antarctica which extend, with some interruptions, across the continent from Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land to Coats Land. ...

): the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

, Marie Byrd Land

Marie Byrd Land (MBL) is an unclaimed region of Antarctica. With an area of , it is the largest unclaimed territory on Earth. It was named after the wife of American naval officer Richard E. Byrd, who explored the region in the early 20th centur ...

, Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as ( Māori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83–79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L. ...

, and Thurston Island

Thurston Island is an ice-covered, glacially dissected island, long, wide and in area, lying a short way off the northwest end of Ellsworth Land, Antarctica. It is the third-largest island of Antarctica, after Alexander Island and Berkner Isl ...

; the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubou ...

and Ellsworth–Whitmore Mountains (in Antarctica) were rotated 90° in opposite directions; and South America south of the Gastre Fault (often referred to as Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and ...

) was pushed westward. The history of the Africa-Antarctica break-up can be studied in great detail in the fracture zones and magnetic anomalies flanking the Southwest Indian Ridge

The Southwest Indian Ridge (SWIR) is a mid-ocean ridge located along the floors of the south-west Indian Ocean and south-east Atlantic Ocean. A divergent tectonic plate boundary separating the Somali Plate to the north from the Antarctic Plat ...

.

The Madagascar block and the Mascarene Plateau

The Mascarene Plateau is a submarine plateau in the Indian Ocean, north and east of Madagascar. The plateau extends approximately , from Seychelles in the north to Réunion in the south. The plateau covers an area of over of shallow water, wi ...

, stretching from the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

to Réunion

Réunion (; french: La Réunion, ; previously ''Île Bourbon''; rcf, label= Reunionese Creole, La Rényon) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas department and region of France. It is located approximately east of the island o ...

, were broken off India, causing Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

and Insular India

The term Insular India refers to the isolated landmass which became the Indian subcontinent. Across the latter stages of the Cretaceous and most of the Paleocene, following the breakup of Gondwana, the Indian subcontinent remained an isolated land ...

to be separate landmasses: elements of this break-up nearly coincide with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With th ...

. The India–Madagascar–Seychelles separations appear to coincide with the eruption of the Deccan basalts, whose eruption site may survive as the Réunion hotspot

The Réunion hotspot is a volcanic hotspot which currently lies under the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. The Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and the southern part of the Mascarene Plateau are volcanic traces of the Réunion hotspot.

The hotsp ...

. The Seychelles and the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipela ...

are now separated by the Central Indian Ridge

The Central Indian Ridge (CIR) is a north–south-trending mid-ocean ridge in the western Indian Ocean.

Geological setting

The morphology of the CIR is characteristic of slow to intermediate ridges. The axial valley is 500–1000 m deep; ...

.

During the initial break-up in the Early Jurassic a marine transgression

A marine transgression is a geologic event during which sea level rises relative to the land and the shoreline moves toward higher ground, which results in flooding. Transgressions can be caused by the land sinking or by the ocean basins filling ...

swept over the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

covering Triassic planation surface

In geology and geomorphology a planation surface is a large-scale surface that is almost flat with the possible exception of some residual hills. The processes that form planation surfaces are labelled collectively planation and are exogenic (ch ...

s with sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

, limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

, shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments ( silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especial ...

, marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part o ...

s and evaporite

An evaporite () is a water-soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as ocean ...

s.

Opening of eastern Indian Ocean

East Gondwana, comprising Antarctica, Madagascar, India, and Australia, began to separate from Africa. East Gondwana then began to break up when India moved northwest from Australia-Antarctica. TheIndian Plate

The Indian Plate (or India Plate) is a minor tectonic plate straddling the equator in the Eastern Hemisphere. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, the Indian Plate broke away from the other fragments of Gondwana , began mo ...

and the Australian Plate

The Australian Plate is a major tectonic plate in the eastern and, largely, southern hemispheres. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, Australia remained connected to India and Antarctica until approximately when India broke ...

are now separated by the Capricorn Plate and its diffuse boundaries. During the opening of the Indian Ocean, the Kerguelen hotspot

The Kerguelen hotspot is a volcanic hotspot at the Kerguelen Plateau in the Southern Indian Ocean. The Kerguelen hotspot has produced basaltic lava for about 130 million years and has also produced the Kerguelen Islands, Naturaliste Plateau, Hear ...

first formed the Kerguelen Plateau

The Kerguelen Plateau (, ), also known as the Kerguelen–Heard Plateau, is an oceanic plateau and a large igneous province (LIP) located on the Antarctic Plate, in the southern Indian Ocean. It is about to the southwest of Australia and is ...

on the Antarctic Plate

The Antarctic Plate is a tectonic plate containing the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau, and some remote islands in the Southern Ocean and other surrounding oceans. After breakup from Gondwana (the southern part of the superconti ...

and then the Ninety East Ridge

The Ninety East Ridge (also rendered as Ninetyeast Ridge, 90E Ridge or 90°E Ridge) is a mid-ocean ridge on the Indian Ocean floor named for its near-parallel strike along the 90th meridian at the center of the Eastern Hemisphere. It is approxim ...

on the Indian Plate

The Indian Plate (or India Plate) is a minor tectonic plate straddling the equator in the Eastern Hemisphere. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, the Indian Plate broke away from the other fragments of Gondwana , began mo ...

at . The Kerguelen Plateau and the Broken Ridge, the southern end of the Ninety East Ridge, are now separated by the Southeast Indian Ridge

The Southeast Indian Ridge (SEIR) is a mid-ocean ridge in the southern Indian Ocean. A divergent tectonic plate boundary stretching almost between the Rodrigues Triple Junction () in the Indian Ocean and the Macquarie Triple Junction () in the ...

.

Separation between Australia and East Antarctica

East Antarctica, also called Greater Antarctica, constitutes the majority (two-thirds) of the Antarctic continent, lying on the Indian Ocean side of the continent, separated from West Antarctica by the Transantarctic Mountains. It lies almost ...

began with seafloor spreading occurring . A shallow seaway developed over the South Tasman Rise during the Early Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configurat ...

and as oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic c ...

started to separate the continents during the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', "da ...

global ocean temperature dropped significantly. A dramatic shift from arc- to rift magmatism separated Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as ( Māori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83–79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L. ...

, including New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island country ...

, the Campbell Plateau, Chatham Rise

The Chatham Rise is an area of ocean floor to the east of New Zealand, forming part of the Zealandia continent. It stretches for some from near the South Island in the west, to the Chatham Islands in the east. It is New Zealand's most productive ...

, Lord Howe Rise

The Lord Howe Rise is a deep sea plateau which extends from south west of New Caledonia to the Challenger Plateau, west of New Zealand in the south west of the Pacific Ocean. To its west is the Tasman Basin and to the east is the New Caled ...

, Norfolk Ridge, and New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

, from West Antarctica

West Antarctica, or Lesser Antarctica, one of the two major regions of Antarctica, is the part of that continent that lies within the Western Hemisphere, and includes the Antarctic Peninsula. It is separated from East Antarctica by the Transan ...

.

Opening of South Atlantic Ocean

The opening of the South Atlantic Ocean divided West Gondwana (South America and Africa), but there is a considerable debate over the exact timing of this break-up. Rifting propagated from south to north along Triassic–Early Jurassic lineaments, but intra-continental rifts also began to develop within both continents in Jurassic–Cretaceous sedimentary basins; subdividing each continent into three sub-plates. Rifting began at Falkland latitudes, forcing Patagonia to move relative to the still static remainder of South America and Africa, and this westward movement lasted until the Early Cretaceous . From there rifting propagated northward during the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous most likely forcing dextral movements between sub-plates on either side. South of theWalvis Ridge

The Walvis Ridge (''walvis'' means whale in Dutch and Afrikaans) is an aseismic ocean ridge in the southern Atlantic Ocean. More than in length, it extends from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, near Tristan da Cunha and the Gough Islands, to the Africa ...

and Rio Grande Rise

The Rio Grande Rise, also called the Rio Grande Elevation or Bromley Plateau, is an aseismic ocean ridge in the southern Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Brazil. Together with the Walvis Ridge off Africa, the Rio Grande Rise forms a V-shaped stru ...

the Paraná and Etendeka magmatics resulted in further ocean-floor spreading and the development of rifts systems on both continents, including the Central African Rift System and the Central African Shear Zone

The Central African Shear Zone (CASZ) (or Shear System) is a wrench fault system extending in an ENE direction from the Gulf of Guinea through Cameroon into Sudan.

The structure is not well understood.

, there was still no general agreement about ...

which lasted until . At Brazilian latitudes spreading is more difficult to assess because of the lack of palaeo-magnetic data, but rifting occurred in Nigeria at the Benue Trough

The Benue Trough is a major geological structure underlying a large part of Nigeria and extending about 1,000 km northeast from the Bight of Benin to Lake Chad. It is part of the broader West and Central African Rift System.

Location

The t ...

. North of the Equator the rifting began after and continued until .

Early Andean orogeny

The first phases ofAndean orogeny

The Andean orogeny ( es, Orogenia andina) is an ongoing process of orogeny that began in the Early Jurassic and is responsible for the rise of the Andes mountains. The orogeny is driven by a reactivation of a long-lived subduction system along ...

in the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous ( geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous ( chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pr ...

were characterised by extensional tectonics

Extensional tectonics is concerned with the structures formed by, and the tectonic processes associated with, the stretching of a planetary body's crust or lithosphere.

Deformation styles

The types of structure and the geometries formed depend ...

, rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben wi ...

ing, the development of back-arc basin

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most o ...

s and the emplacement of large batholith

A batholith () is a large mass of intrusive igneous rock (also called plutonic rock), larger than in area, that forms from cooled magma deep in Earth's crust. Batholiths are almost always made mostly of felsic or intermediate rock types, such ...

s. This development is presumed to have been linked to the subduction of cold oceanic

Oceanic may refer to:

*Of or relating to the ocean

*Of or relating to Oceania

**Oceanic climate

**Oceanic languages

**Oceanic person or people, also called "Pacific Islander(s)"

Places

* Oceanic, British Columbia, a settlement on Smith Island, ...

lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

. During the mid to Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', t ...

(), the Andean orogeny changed significantly in character. Warmer and younger oceanic lithosphere is believed to have started to be subducted beneath South America around this time. Such kind of subduction is held responsible not only for the intense contractional deformation

Deformation can refer to:

* Deformation (engineering), changes in an object's shape or form due to the application of a force or forces.

** Deformation (physics), such changes considered and analyzed as displacements of continuum bodies.

* Defo ...

that different lithologies were subject to, but also the uplift and erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is di ...

known to have occurred from the Late Cretaceous onward. Plate tectonic

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

reorganisation since the mid-Cretaceous might also have been linked to the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

. Another change related to mid-Cretaceous plate tectonic rearrangement was the change of subduction direction of the oceanic lithosphere that went from having south-east motion to having a north-east motion at about 90 million years ago. While subduction direction changed, it remained oblique (and not perpendicular) to the coast of South America, and the direction change affected several subduction zone

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

-parallel faults including Atacama

The Atacama Desert ( es, Desierto de Atacama) is a desert plateau in South America covering a 1,600 km (990 mi) strip of land on the Pacific coast, west of the Andes Mountains. The Atacama Desert is the driest nonpolar desert in the ...

, Domeyko and Liquiñe-Ofqui.

Cenozoic

Insular India

The term Insular India refers to the isolated landmass which became the Indian subcontinent. Across the latter stages of the Cretaceous and most of the Paleocene, following the breakup of Gondwana, the Indian subcontinent remained an isolated land ...

began to collide with Asia circa , forming the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, Ind ...

, since which more than of crust has been absorbed by the Himalayan-Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Tama ...

an orogen. During the Cenozoic, the orogen resulted in the construction of the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the ...

between the Tethyan Himalayas in the south and the Kunlun

The Kunlun Mountains ( zh, s=昆仑山, t=崑崙山, p=Kūnlún Shān, ; ug, كۇئېنلۇن تاغ تىزمىسى / قۇرۇم تاغ تىزمىسى ) constitute one of the longest mountain chains in Asia, extending for more than . In the bro ...

and Qilian mountains in the north.

Later, South America was connected to North America via the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the countr ...

, cutting off a circulation of warm water and thereby making the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada ( Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm ( Greenland), Finland, Icel ...

colder, as well as allowing the Great American Interchange

The Great American Biotic Interchange (commonly abbreviated as GABI), also known as the Great American Interchange and the Great American Faunal Interchange, was an important late Cenozoic paleozoogeographic biotic interchange event in which la ...

.

The break-up of Gondwana can be said to continue in eastern Africa at the Afar Triple Junction

The Afar Triple Junction (also called the Afro-Arabian Rift System) is located along a divergent plate boundary dividing the Nubian, Somali, and Arabian plates. This area is considered a present-day example of continental rifting leading to se ...

, which separates the Arabian

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, Nubian, and Somali plates, resulting in rifting in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

and East African Rift

The East African Rift (EAR) or East African Rift System (EARS) is an active continental rift zone in East Africa. The EAR began developing around the onset of the Miocene, 22–25 million years ago. In the past it was considered to be part of a ...

.

Australia–Antarctica separation

In the EarlyCenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configurat ...

, Australia was still connected to Antarctica 35–40° south of its current location and both continents were largely unglaciated. A rift between the two developed but remained an embayment until the Eocene-Oligocene boundary when the Circumpolar Current developed and the glaciation of Antarctica began.

Australia was warm and wet during the Palaeocene and dominated by rainforest. The opening of the Tasman Gateway at the Eocene-Oligocene boundary () resulted in abrupt cooling but the Oligocene became a period of high rainfall with swamps in southeast Australia. During the Miocene, a warm and humid climate developed with pockets of rainforests in central Australia, but before the end of the period, colder and drier climate severely reduced this rainforest. A brief period of increased rainfall in the Pliocene was followed by drier climate which favoured grassland. Since then, the fluctuation between wet interglacial periods and dry glacial periods has developed into the present arid regime. Australia has thus experienced various climate changes over a 15-million-year period with a gradual decrease in precipitation.

The Tasman Gateway between Australia and Antarctica began to open . Palaeontological evidence indicates the Antarctic Circumpolar Current

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is an ocean current that flows clockwise (as seen from the South Pole) from west to east around Antarctica. An alternative name for the ACC is the West Wind Drift. The ACC is the dominant circulation feat ...

(ACC) was established in the Late Oligocene with the full opening of the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

and the deepening of the Tasman Gateway. The oldest oceanic crust in the Drake Passage, however, is -old which indicates that the spreading between the Antarctic and South American plates began near the Eocene/Oligocene boundary. Deep sea environments in Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

and the North Scotia Ridge during the Eocene and Oligocene indicate a "Proto-ACC" opened during this period. Later, , a series of events severally restricted the Proto-ACC: change to shallow marine conditions along the North Scotia Ridge; closure of the Fuegan Seaway, the deep sea that existed in Tierra del Fuego; and uplift of the Patagonian Cordillera. This, together with the reactivated Iceland plume

The Iceland hotspot is a hotspot which is partly responsible for the high volcanic activity which has formed the Iceland Plateau and the island of Iceland.

Iceland is one of the most active volcanic regions in the world, with eruptions occur ...

, contributed to global warming. During the Miocene, the Drake Passage began to widen, and as water flow between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

increased, the renewed ACC resulted in cooler global climate.

Since the Eocene, the northward movement of the Australian Plate has resulted in an arc-continent

A continental arc is a type of volcanic arc occurring as an "arc-shape" topographic high region along a continental margin. The continental arc is formed at an active continental margin where two tectonic plates meet, and where one plate has conti ...

collision with the Philippine

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Caroline plates and the uplift of the New Guinea Highlands

The New Guinea Highlands, also known as the Central Range or Central Cordillera, is a long chain of mountain ranges on the island of New Guinea, including the island's tallest peak, Puncak Jaya , the highest mountain in Oceania. The range is ho ...

. From the Oligocene to the late Miocene, the climate in Australia, dominated by warm and humid rainforests before this collision, began to alternate between open forest and rainforest before the continent became the arid or semiarid landscape it is today.

Biogeography

The adjective "Gondwanan" is in common use in

The adjective "Gondwanan" is in common use in biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevatio ...

when referring to patterns of distribution of living organisms, typically when the organisms are restricted to two or more of the now-discontinuous regions that were once part of Gondwana, including the Antarctic flora

Antarctic flora are a distinct community of vascular plants which evolved millions of years ago on the supercontinent of Gondwana. Presently, species of Antarctica flora reside on several now separated areas of the Southern Hemisphere, includin ...

. For example, the plant family Proteaceae

The Proteaceae form a family of flowering plants predominantly distributed in the Southern Hemisphere. The family comprises 83 genera with about 1,660 known species. Together with the Platanaceae and Nelumbonaceae, they make up the order Pro ...

, known from all continents in the Southern Hemisphere, has a "Gondwanan distribution" and is often described as an archaic, or relict

A relict is a surviving remnant of a natural phenomenon.

Biology

A relict (or relic) is an organism that at an earlier time was abundant in a large area but now occurs at only one or a few small areas.

Geology and geomorphology

In geology, a r ...

, lineage. The distributions in the Proteaceae is, nevertheless, the result of both Gondwanan rafting and later oceanic dispersal.

Post-Cambrian diversification

During theSilurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleozo ...

, Gondwana extended from the Equator (Australia) to the South Pole (North Africa and South America) whilst Laurasia was located on the Equator opposite to Australia. A short-lived Late Ordovician glaciation

The Andean-Saharan glaciation, also known as the Early Palaeozoic Icehouse, the Early Palaeozoic Ice Age, the Late Ordovician glaciation, the end-Ordovician glaciation, or the Hirnantian glaciation, occurred during the Paleozoic from approximately ...

was followed by a Silurian Hot House period. The End-Ordovician extinction, which resulted in 27% of marine invertebrate families and 57% of genera going extinct, occurred during this shift from Ice House to Hot House.

By the end of the Ordovician, ''Cooksonia

''Cooksonia'' is an extinct group of primitive land plants, treated as a genus, although probably not monophyletic. The earliest ''Cooksonia'' date from the middle of the Silurian (the Wenlock epoch); the group continued to be an important c ...

'', a slender, ground-covering plant, became the first vascular plant to establish itself on land. This first colonisation occurred exclusively around the Equator on landmasses then limited to Laurasia and, in Gondwana, to Australia. In the Late Silurian, two distinctive lineages, zosterophyll

The zosterophylls are a group of extinct land plants that first appeared in the Silurian period. The taxon was first established by Banks in 1968 as the subdivision Zosterophyllophytina; they have since also been treated as the division Zoste ...

s and rhyniophytes, had colonised the tropics. The former evolved into the lycopods

Lycopodiopsida is a class of vascular plants known as lycopods, lycophytes or other terms including the component lyco-. Members of the class are also called clubmosses, firmosses, spikemosses and quillworts. They have dichotomously branching s ...

that were to dominate the Gondwanan vegetation over a long period, whilst the latter evolved into horsetails

''Equisetum'' (; horsetail, snake grass, puzzlegrass) is the only living genus in Equisetaceae, a family of ferns, which reproduce by spores rather than seeds.

''Equisetum'' is a "living fossil", the only living genus of the entire subclass E ...

and gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( lit. revealed seeds) are a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, ''Ginkgo'', and gnetophytes, forming the clade Gymnospermae. The term ''gymnosperm'' comes from the composite word in el, γυμνόσ ...

s. Most of Gondwana was located far from the Equator during this period and remained a lifeless and barren landscape.

West Gondwana drifted north during the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, w ...

, bringing Gondwana and Laurasia close together. Global cooling contributed to the Late Devonian extinction

The Late Devonian extinction consisted of several extinction events in the Late Devonian Epoch, which collectively represent one of the five largest mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The term primarily refers to a major exti ...

(19% of marine families and 50% of genera went extinct) and glaciation occurred in South America. Before Pangaea had formed, terrestrial plants, such as pteridophyte

A pteridophyte is a vascular plant (with xylem and phloem) that disperses spores. Because pteridophytes produce neither flowers nor seeds, they are sometimes referred to as "cryptogams", meaning that their means of reproduction is hidden. Ferns, ...

s, began to diversify rapidly resulting in the colonisation of Gondwana. The Baragwanathia

''Baragwanathia'' is a genus of extinct lycopsid plants of Late Silurian to Early Devonian age (), fossils of which have been found in Australia, Canada, China and Czechia. The name derives from William Baragwanath who discovered the first speci ...

Flora, found only in the Yea Beds of Victoria, Australia, occurs in two strata separated by or 30 Ma; the upper assemblage is more diverse and includes Baragwanathia, the first primitive herbaceous

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition o ...

lycopod to evolve from the zosterophylls. During the Devonian, giant club mosses replaced the Baragwanathia Flora, introducing the first trees, and by the Late Devonian this first forest was accompanied by the progymnosperm

The progymnosperms are an extinct group of woody, spore-bearing plants that is presumed to have evolved from the trimerophytes, and eventually gave rise to the gymnosperms, ancestral to acrogymnosperms and angiosperms (flowering plants). They h ...

s, including the first large trees ''Archaeopteris

''Archaeopteris'' is an extinct genus of progymnosperm tree with fern-like leaves. A useful index fossil, this tree is found in strata dating from the Upper Devonian to Lower Carboniferous (), the oldest fossils being 385 million years old, and ...

''. The Late Devonian extinction probably also resulted in osteolepiform