Golden Haggadah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Golden Haggadah is a

The Golden Haggadah is a  The Golden Haggadah measures 24.7×19.5 cm, is made of

The Golden Haggadah measures 24.7×19.5 cm, is made of

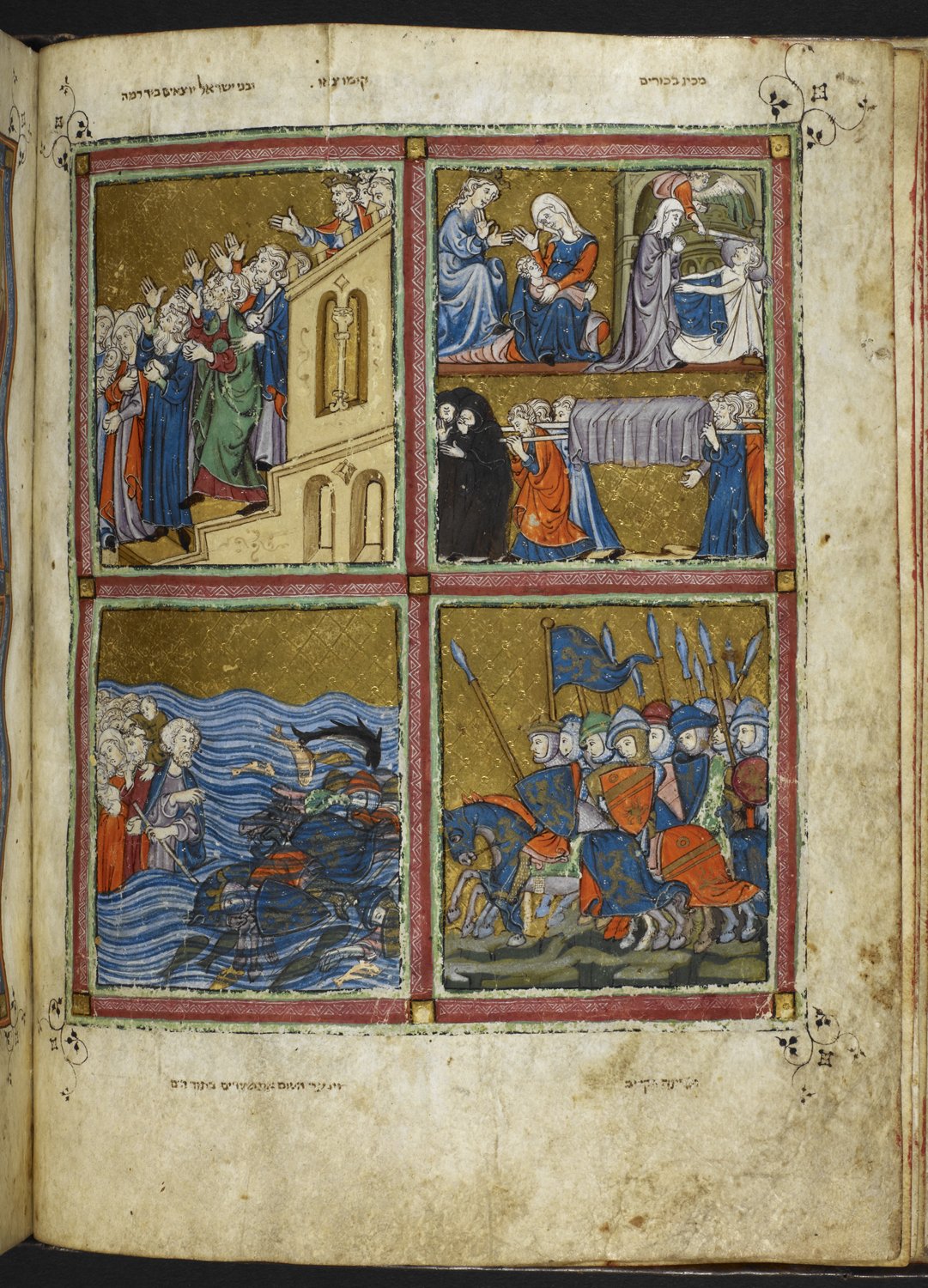

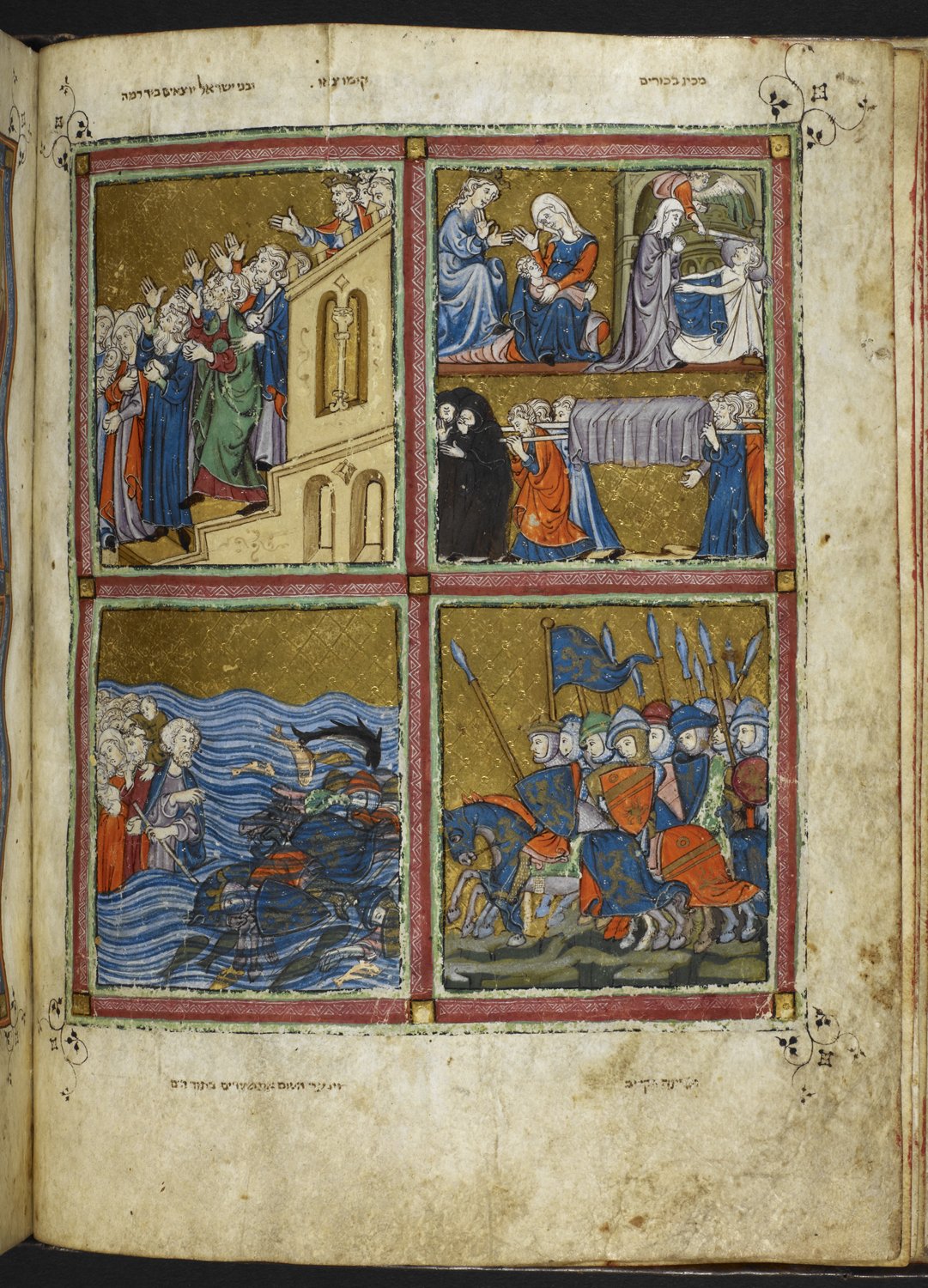

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah all follow a similar layout. They are painted onto the flesh side of the vellum and divided into panels of four frames read in the same direction as the Hebrew language, from right to left and from top to bottom. The panels each consist of a background in burnished gold with a diamond pattern stamped onto it. A border is laid around each panel made of red or blue lines, the inside of which are decorated with

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah all follow a similar layout. They are painted onto the flesh side of the vellum and divided into panels of four frames read in the same direction as the Hebrew language, from right to left and from top to bottom. The panels each consist of a background in burnished gold with a diamond pattern stamped onto it. A border is laid around each panel made of red or blue lines, the inside of which are decorated with

File:Golden haggadah - scenes from genesis - BL Add.27210, f.2v.jpg

File:Golden Haggadah cleaning.jpg

File:Miriam, the golden Haggadah.jpg

File:Golden Haggadah Pharaoh and the Midwives.jpg

File:Golden Haggadah Jacob Blessing Ephraim and Manasseh.jpg

File:Enluminure Sefarade, Haggadah a.jpg

A scan of the Haggadah

The Golden Haggadah is a

The Golden Haggadah is a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared manuscript, document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as marginalia, borders and Miniature (illuminated manuscript), miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Churc ...

originating around c. 1320–1330 in Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

. It is an example of an Illustrated Haggadah

The Haggadah (, "telling"; plural: Haggadot) is a foundational Jewish text that sets forth the order of the Passover Seder. According to Jewish practice, reading the Haggadah at the Seder table fulfills the mitzvah incumbent on every Jew to reco ...

, a religious text for Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

. It contains many lavish illustrations in the High Gothic

High Gothic was a period of Gothic architecture in the 13th century, from about 1200 to 1280, which saw the construction of a series of refined and richly decorated cathedrals of exceptional height and size. It appeared most prominently in France ...

style with Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style combined its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century It ...

influence, and is perhaps one of the most distinguished illustrated manuscripts created in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. The Golden Haggadah is now in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. Based in London, it is one of the largest libraries in the world, with an estimated collection of between 170 and 200 million items from multiple countries. As a legal deposit li ...

and can be fully viewed as part of their Digitized Manuscript Collection MS 27210.

The Golden Haggadah measures 24.7×19.5 cm, is made of

The Golden Haggadah measures 24.7×19.5 cm, is made of vellum

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. It is often distinguished from parchment, either by being made from calfskin (rather than the skin of other animals), or simply by being of a higher quality. Vellu ...

, and consists of 101 leaves. It is a Hebrew text written in square Sephardi

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

script. There are fourteen full-page miniatures, each consisting of four scenes on a gold ground

Gold ground (both a noun and adjective) or gold-ground (adjective) is a term in art history for a style of images with all or most of the background in a solid gold colour. Historically, real gold leaf has normally been used, giving a luxurious ...

. It has a seventeenth-century Italian binding of dark brown sheepskin. The manuscript has outer decorations of blind-tooled fan-shaped motifs pressed into the leather cover with a heated brass tool on the front and back.

The Golden Haggadah is a selection of texts to be read on the first night of Passover, dealing with the Exodus of the Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

. It is composed of three main parts. These are fourteen full pages of miniatures, a decorated Haggadah text, and a selection of 100 Passover piyyut

A piyyuṭ (plural piyyuṭim, ; from ) is a Jewish liturgical poem, usually designated to be sung, chanted, or recited during religious services. Most piyyuṭim are in Mishnaic Hebrew or Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, and most follow some p ...

im liturgical poems.

The first section of miniatures portray the events of the Biblical books of Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

and Exodus, ranging from Adam

Adam is the name given in Genesis 1–5 to the first human. Adam is the first human-being aware of God, and features as such in various belief systems (including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Islam).

According to Christianity, Adam ...

naming the animals and concluding with the song of Miriam

Miriam (, lit. ‘rebellion’) is described in the Hebrew Bible as the daughter of Amram and Jochebed, and the older sister of Moses and Aaron. She was a prophetess and first appears in the Book of Exodus.

The Torah refers to her as "Miria ...

. The following set of illustrations consist of illustrated steps on the preparations needed for Passover. The second section of the decorated Haggadah text contains text decorated with initial word panels. These also included three text illustrations showing a dragon drinking wine (fol.27), the mazzah (fol.44v), and the maror

''Maror'' ( ''mārōr'') are the bitter herbs eaten at the Passover Seder in keeping with the biblical commandment "with bitter herbs they shall eat it." ( Exodus 12:8). The Maror is one of the symbolic foods placed on the Passover Seder pla ...

(fol.45v). The concluding section of the piyyutim consists of only initial-word panels.

History

The Golden Haggadah is presumed to have been created sometime around 1320–1330. While originating inSpain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, it is believed that the manuscript found its way to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

in possession of Jews banished from the country in 1492.

The original illustrators for the manuscript are unknown. Based on artistic evidence, the standing theory is that there were at least two illustrators. While there is no evidence of different workshops

Beginning with the Industrial Revolution era, a workshop may be a room, rooms or building which provides both the area and tools (or machinery) that may be required for the manufacture or repair of manufactured goods. Workshops were the only ...

producing the manuscript, there are two distinct artistic styles used respectively in groupings of eight folios on single sides of the pages. The first noticeable style is an artist who created somewhat standardized faces for their figures, but was graceful in their work and balanced with their color. The second style seen was very coarse and energetic in comparison.

The original patron who commissioned the manuscript is unknown. The prevailing theory is that the first known owner was Rabbi Joav Gallico of Asti

Asti ( , ; ; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) of 74,348 inhabitants (1–1–2021) located in the Italy, Italian region of Piedmont, about east of Turin, in the plain of the Tanaro, Tanaro River. It is the capital of the province of Asti and ...

, who presented it as a gift to his daughter Rosa's bridegroom, Eliah Ravà, on the occasion of their wedding in 1602. The evidence for this theory is the addition to the manuscript of a title page with an inscription and another page containing the Gallico family coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

in recognition of the ceremony. The commemorative text inscribed in the title page translates from the Hebrew as:

''“NTNV as a gift ..the honored Mistress Rosa,''

''(May she be blessed among the women of the tent), daughter of our illustrious''

''Honored Teacher Rabbi Yoav''

''Gallico, (may his Rock preserve him) to his son-in-law, the learned''

''Honored Teacher Elia (may his Rock preserve him)''

''Son of the safe, our Honored Teacher, the Rabbi R. Menahem Ravà (May he live Many good years)''

''On the day of his wedding and the day of the rejoicing of his heart,''

''Here at Carpi, the tenth of the month of Heshvan, Heh Shin Samekh Gimel (1602)”''

The translation of this inscription has led to debate on who originally gave the manuscript, either the bride Rosa or her father Rabbi Joav. This confusion originates with translation difficulties of the first word and a noticeable gap that follows it, leaving out the word “to” or “by”. There are three theorized ways to read this translation.

The current theory is a translation of ''“He gave it etanoas a gift. . . gnores references to Mistress Rosa . .to his son-in-law. . .Elia.”'' This translation works to ignore the reference to the bride and states that Rabbi Joav presented the manuscript to his new son-in-law. This presents the problem of why the bride would be mentioned after the use of the verb “he gave” and leaving out the follow-up of “to” seen as prefix “le”. In support of this theory is that the prefix “le” is used in the second half of the inscription pointing to the groom Elia being the receiver, thus making this the prevailing theory.

Another translation is ''“They gave it atnuas a gift. . .Mistress Rosa (and her father?) to. . . his (her father’s) son-in-law Elia.”'' This supports the theory that the manuscript was given by both Rosa and Rabbi Joav together. The problem with this reading is the strange wording used to describe Rabbi Joav's relationship to Elia and his grammatical placement after Rosa's name as an afterthought.

The most grammatically correct translation is ''“It was given etano (or possibly Netanto)as a gift y . .Mistress Rosa to. . .(her father’s) son-in-law Elia.”''. This suggests that the manuscript was originally Rosa's and she gifted it to her groom, Elia. This theory also has its flaws in that this would mean the male version of “to give” was used for Rosa and not the feminine version. In addition, Elia is referred to as the son-in-law of her father, rather than merely her groom, which makes little sense if Rabbi Joav was not involved in some form.

Additional changes to the manuscript that can be dated include a mnemonic poem of the laws and customs of Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

on blank pages between miniatures added in the seventeenth century, a birth entry of a son in Italy 1689, and the signatures of censors for the years 1599, 1613, and 1629.

The Golden Haggadah is now in the London British Library shelf mark MS 27210. It was acquired by the British Museum in 1865 as part of the collection of Joseph Almanzi of Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

.

Illuminations

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah all follow a similar layout. They are painted onto the flesh side of the vellum and divided into panels of four frames read in the same direction as the Hebrew language, from right to left and from top to bottom. The panels each consist of a background in burnished gold with a diamond pattern stamped onto it. A border is laid around each panel made of red or blue lines, the inside of which are decorated with

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah all follow a similar layout. They are painted onto the flesh side of the vellum and divided into panels of four frames read in the same direction as the Hebrew language, from right to left and from top to bottom. The panels each consist of a background in burnished gold with a diamond pattern stamped onto it. A border is laid around each panel made of red or blue lines, the inside of which are decorated with arabesque

The arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foliate ...

patterns. This can be seen in the ''Dance of Marian'' where blue lines frame the illustration with red edges and white arabesque decorating inside them. At the edge of each collection of panels can also be found black floral arabesque growing out from the corners.

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah are decidedly High Gothic

High Gothic was a period of Gothic architecture in the 13th century, from about 1200 to 1280, which saw the construction of a series of refined and richly decorated cathedrals of exceptional height and size. It appeared most prominently in France ...

in style. This was influenced by the early 14th-century Catalan School, a Gothic style that is French with Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style combined its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century It ...

influence. It is believed that the two illustrators who worked on the manuscript were influenced by and studied other similar mid-13th-century manuscripts for inspiration, including the famous Morgan Crusader Bible and the Psalter of Saint Louis. This could be seen in the composition of the miniatures' French Gothic styling. The architectural arrangements, however, are in Italianate form as evidenced by the coffer

A coffer (or coffering) in architecture is a series of sunken panels in the shape of a square, rectangle, or octagon in a ceiling, soffit or vault.

A series of these sunken panels was often used as decoration for a ceiling or a vault, al ...

ed ceilings created in the miniatures. Most likely these influences reached Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

in the early 14th century.

Purpose

TheHaggadah

The Haggadah (, "telling"; plural: Haggadot) is a foundational Jewish text that sets forth the order of the Passover Seder. According to Jewish practice, reading the Haggadah at the Seder table fulfills the mitzvah incumbent on every Jew to reco ...

is a copy of the liturgy used during the Seder service of Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

. The most common traits of a Haggadah are the inclusion of an introduction on how to set the table for a seder, an opening mnemonic device for remembering the order of the service, and content based on the Hallel Psalms and three Pedagogic Principles. These written passages are intended to be read aloud at the beginning of Passover and during the family meal. These holy manuscripts were generally collected in private handheld devotional books.

The introduction of Haggadah as illustrated manuscripts occurred around the 13th and 14th centuries. Noble Jewish patrons of the European royal courts would often use the illustration styles of the time to have their Haggadah made into illustrated manuscripts. The manuscripts would have figurative representations of stories and steps to take during service combined with traditional ornamental workings of the highest quality at the time. In regards to the Golden Haggadah, it was most likely created as a part of this trend in the early 14th century. It is considered one of the earliest examples of illustrated Haggadot of Spanish origin to contain a complete sequence of illustrations of the books of Genesis and Exodus. The Sarajevo Haggadah of about 1350 is probably the next best known example from Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

.

Gallery

See also

*Alba Bible

The Alba Bible also known as the Arragel Bible, was created to foster understanding between Christians and Jews. It is an illuminated manuscript containing a translation of the Old Testament made directly from Hebrew into mediaeval Castilian. The ...

* Kennicott Bible

* Damascus Crown

* Cloisters Hebrew Bible

Notes

Additional References

* Bezalel Narkiss, The Golden Haggadah (London: British Library, 1997) artial facsimile * Marc Michael Epstein, Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), pp. 16–17. * Katrin Kogman-Appel, 'The Sephardic Picture Cycles and the Rabbinic Tradition: Continuity and Innovation in Jewish Iconography', Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 60 (1997), 451–82. * Katrin Kogman-Appel, 'Coping with Christian Pictorial Sources: What Did Jewish Miniaturists Not Paint?' Speculum, 75 (2000), 816–58. * Julie Harris, 'Polemical Images in the Golden Haggadah (British Library Add. MS 27210)', Medieval Encounters, 8 (2002), 105–22. * Katrin Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: the Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain (Leiden: Brill, 2004), pp. 179–85. * Sarit Shalev-Eyni, 'Jerusalem and the Temple in Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts: Jewish Thought and Christian Influence', in L'interculturalita dell'ebraismo a cura di Mauro Perani (Ravenna: Longo, 2004), pp. 173–91. * Julie A. Harris, 'Good Jews, Bad Jews, and No Jews at All: Ritual Imagery and Social Standards in the Catalan Haggadot', in Church, State, Vellum, and Stone: Essays on Medieval Spain in Honor of John Williams, ed. by Therese Martin and Julie A. Harris, The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World, 26 (Leiden: Brill, 2005), pp. 275–96 (p. 279, fig. 6). * Katrin Kogman-Appel, Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain. Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), pp. 47–88. * Ilana Tahan, Hebrew Manuscripts: The Power of Script and Image (London, British Library, 2007), pp. 94–97. * Sacred: Books of the Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam (London: British Library, 2007), p. 172 xhibition catalogue * Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah. Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 129–200.External links

A scan of the Haggadah

National Library of Israel

The National Library of Israel (NLI; ; ), formerly Jewish National and University Library (JNUL; ), is the library dedicated to collecting the cultural treasures of Israel and of Judaism, Jewish Cultural heritage, heritage. The library holds more ...

{{Authority control

Haggadah of Pesach

Jewish illuminated manuscripts

British Library additional manuscripts

14th-century illuminated manuscripts