Girondins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit

Twelve deputies represented the département of the Gironde and there were six who sat for this département in both the Legislative Assembly of 1791–1792 and the

Twelve deputies represented the département of the Gironde and there were six who sat for this département in both the Legislative Assembly of 1791–1792 and the

Girondins at first dominated the Jacobin Club, where Brissot's influence had not yet been ousted by

Girondins at first dominated the Jacobin Club, where Brissot's influence had not yet been ousted by

The trial of the 22 began before the Revolutionary Tribunal on 24 October 1793. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. On 31 October, they were borne to the guillotine. It took 36 minutes to decapitate all of them, including Charles Éléonor Dufriche de Valazé, who had committed suicide the previous day upon hearing the sentence he was given.

Of those who escaped to the provinces, after wandering about singly or in groups most were either captured and executed or committed suicide. They included Barbaroux, Buzot,

The trial of the 22 began before the Revolutionary Tribunal on 24 October 1793. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. On 31 October, they were borne to the guillotine. It took 36 minutes to decapitate all of them, including Charles Éléonor Dufriche de Valazé, who had committed suicide the previous day upon hearing the sentence he was given.

Of those who escaped to the provinces, after wandering about singly or in groups most were either captured and executed or committed suicide. They included Barbaroux, Buzot,

excerpt and text search

* François Furet and Mona Ozouf. eds. ''La Gironde et les Girondins''. Paris: éditions Payot, 1991. * Higonnet, Patrice. "The Social and Cultural Antecedents of Revolutionary Discontinuity: Montagnards and Girondins", ''English Historical Review'' (1985): 100#396 pp. 513–544 . * Thomas Lalevée,

National Pride and Republican grandezza: Brissot's New Language for International Politics in the French Revolution

, ''French History and Civilisation'' (Vol. 6), 2015, pp. 66–82. * Lamartine, Alphonse de. ''History of the Girondists, Volume I: Personal Memoirs of the Patriots of the French Revolution'' (1847

online free in Kindle editionVolume 1Volume 2

Volume 3

* Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Anne Hildreth, and Alan B. Spitzer. "Was There a Girondist Faction in the National Convention, 1792–1793?" ''French Historical Studies'' (1988) 11#4 pp.: 519-36. . * Linton, Marisa, ''Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution'' (Oxford University Press, 2013). * Loomis, Stanley, ''Paris in the Terror''. (1964). * Patrick, Alison. "Political Divisions in the French National Convention, 1792–93". ''Journal of Modern History'' (Dec. 1969) 41#4, pp.: 422–474. ; rejects Sydenham's argument & says Girondins were a real faction. * Patrick, Alison. ''The Men of the First French Republic: Political Alignments in the National Convention of 1792'' (1972), comprehensive study of the group's role. * Scott, Samuel F., and Barry Rothaus. ''Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution 1789–1799'' (1985) Vol. 1 pp. 433–3

online

* Sutherland, D. M. G. ''France 1789–1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution'' (2nd ed., 2003) ch. 5. * Sydenham, Michael J. "The Montagnards and Their Opponents: Some Considerations on a Recent Reassessment of the Conflicts in the French National Convention, 1792–93", ''Journal of Modern History'' (1971) 43#2 pp. 287–293 ; argues that the Girondins faction was mostly a myth created by Jacobins. * Whaley, Leigh Ann. ''Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution''. Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

political faction

A political faction is a group of individuals that share a common political purpose but differs in some respect to the rest of the entity. A faction within a group or political party may include fragmented sub-factions, "parties within a party," ...

during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

. Together with the Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

*Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of th ...

, they initially were part of the Jacobin movement. They campaigned for the end of the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic ( constitutional monar ...

, but then resisted the spiraling momentum of the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

, which caused a conflict with the more radical Montagnards. They dominated the movement until their fall in the insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, which resulted in the domination of the Montagnards and the purge and eventual mass execution of the Girondins. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

The Girondins were a group of loosely affiliated individuals rather than an organized political party and the name was at first informally applied because the most prominent exponents of their point of view were deputies to the Legislative Assembly from the département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level (" territorial collectivities"), between the administrative regions and the communes. Ninety ...

of Gironde in southwest France. Girondin leader Jacques Pierre Brissot proposed an ambitious military plan to spread the Revolution internationally, therefore the Girondins were the war party in 1792–1793. Other prominent Girondins included Jean Marie Roland

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jea ...

and his wife Madame Roland. They also had an ally in the English-born American activist Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

.

Brissot and Madame Roland were executed and Jean Roland (who had gone into hiding) committed suicide when he learned about the execution. Paine was imprisoned, but he narrowly escaped execution. The famous painting ''The Death of Marat

''The Death of Marat'' (french: La Mort de Marat or ''Marat Assassiné'') is a 1793 painting by Jacques-Louis David depicting the artist's friend and murdered French revolutionary leader, Jean-Paul Marat. One of the most famous images from the e ...

'' depicts the fiery radical journalist and denouncer of the Girondins Jean-Paul Marat after being stabbed to death in his bathtub by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer. Corday did not attempt to flee and was arrested and executed.

Identity

The collective name "Girondins" is used to describe "a loosely knit group of French deputies who contested the Montagnards for control of the National Convention". They were never an official organization or political party. The name itself was bestowed not by any of its alleged members but by theMontagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

*Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of th ...

, "who claimed as early as April 1792 that a counterrevolutionary faction had coalesced around deputies of the department of the Gironde". Jacques-Pierre Brissot, Jean Marie Roland

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jea ...

and François Buzot

François Nicolas Léonard Buzot (1 March 176018 June 1794) was a French politician and leader of the French Revolution.

Biography

Early life

Born at Évreux, Eure, he studied Law, and, at the outbreak of the Revolution was a lawyer in his hom ...

were among the most prominent of such deputies and contemporaries called their supporters ''Brissotins'', ''Rolandins'', or ''Buzotins'', depending on which politician was being blamed for their leadership. Other names were employed at the time too, but "Girondins" ultimately became the term favored by historians. The term became standard with Alphonse de Lamartine's ''History of the Girondins'' in 1847.

History

Rise

Twelve deputies represented the département of the Gironde and there were six who sat for this département in both the Legislative Assembly of 1791–1792 and the

Twelve deputies represented the département of the Gironde and there were six who sat for this département in both the Legislative Assembly of 1791–1792 and the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

of 1792–1795. Five were lawyers: Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud, Marguerite-Élie Guadet

Marguerite-Élie Guadet (, 20 July 1758 – 19 June 1794) was a French political figure of the Revolutionary period.

Rise to prominence

Born in Saint-Émilion, Gironde, Aquitaine, he had already gained a reputation as a lawyer in Bordeaux by ...

, Armand Gensonné

Armand Gensonné (, 10 August 175831 October 1793) was a French politician.

The son of a military surgeon, he was born in Bordeaux, Gascony, and studied Law before the outbreak of the French Revolution, becoming lawyer of the ''parlement'' of ...

, Jean Antoine Laffargue de Grangeneuve and Jean Jay (who was also a Protestant pastor). The other, Jean François Ducos, was a tradesman. In the Legislative Assembly, they represented a compact body of opinion which, though not as yet definitely republican (i.e. against the monarchy), was considerably more "advanced" than the moderate royalism of the majority of the Parisian deputies.

A group of deputies from elsewhere became associated with these views, most notably the Marquis de Condorcet, Claude Fauchet, Marc David Lasource, Maximin Isnard

Maximin Isnard (; 16 November 1755 Grasse, Alpes-Maritimes – 12 March 1825 Grasse), French revolutionary, was a dealer in perfumery at Draguignan when he was elected deputy for the ''département'' of the Var to the Legislative Assembly, where ...

, the Comte de Kersaint, Henri Larivière and above all Jacques Pierre Brissot, Jean Marie Roland and Jérôme Pétion, who was elected mayor of Paris in succession to Jean Sylvain Bailly

Jean Sylvain Bailly (; 15 September 1736 – 12 November 1793) was a French astronomer, mathematician, freemason, and political leader of the early part of the French Revolution. He presided over the Tennis Court Oath, served as the mayor of Par ...

on 16 November 1791.

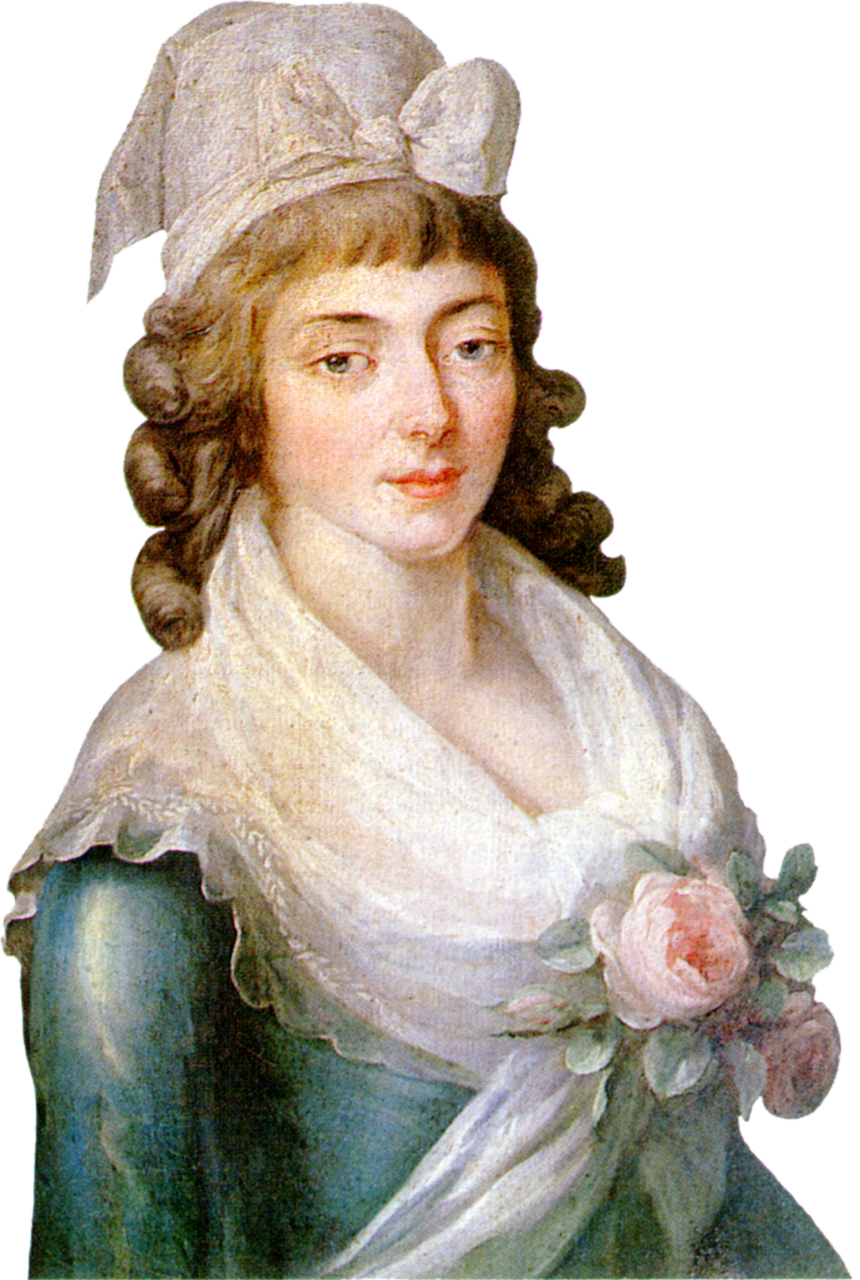

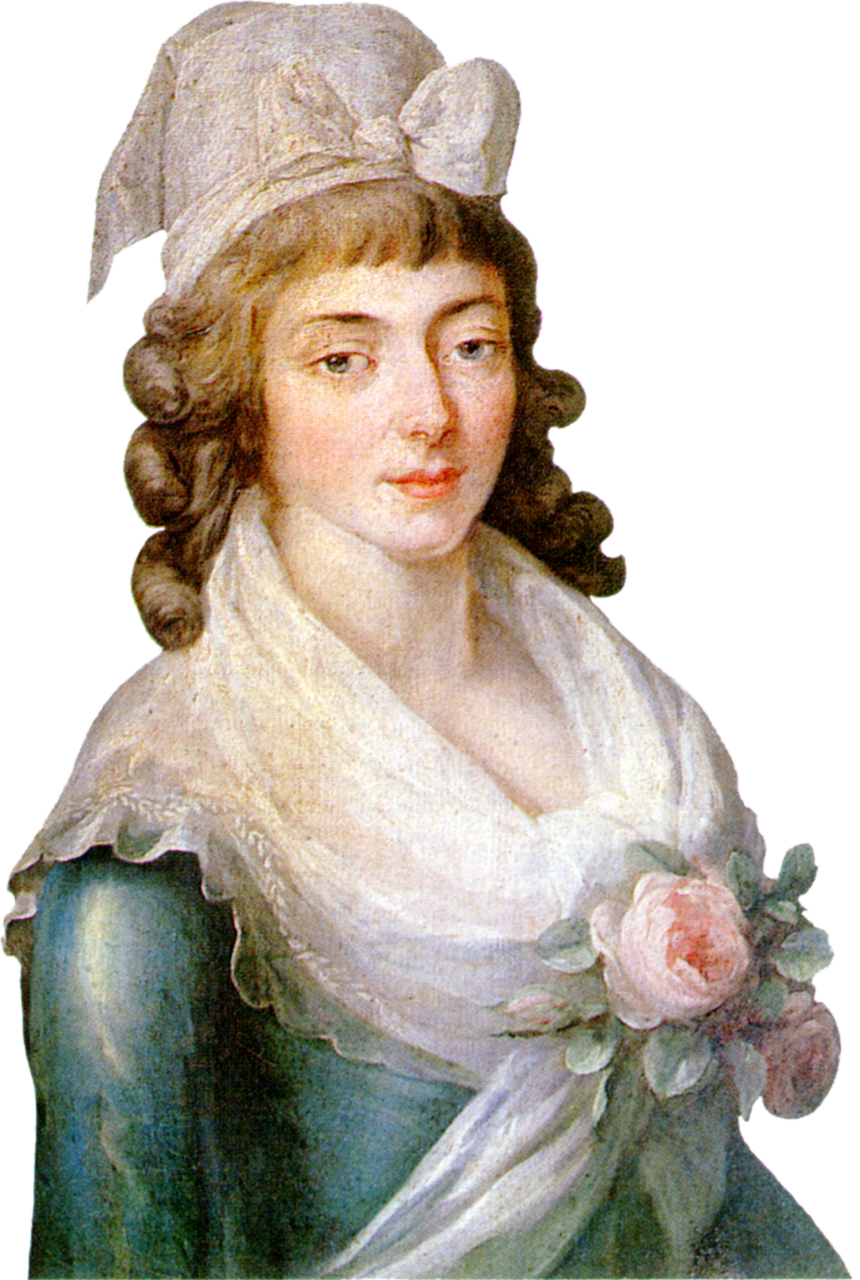

Madame Roland, whose salon became their gathering place, had a powerful influence on the spirit and policy of the Girondins with her "romantic republicanism". The party cohesion they possessed was connected to the energy of Brissot, who came to be regarded as their mouthpiece in the Assembly and in the Jacobin Club, hence the name "Brissotins" for his followers. The group was identified by its enemies at the start of the National Convention (20 September 1792). "Brissotins" and "Girondins" were terms of opprobrium used by their enemies in a separate faction of the Jacobin Club, who freely denounced them as enemies of democracy.

Foreign policy

In the Legislative Assembly, the Girondins represented the principle of democratic revolution within France and patriotic defiance to the European powers. They supported an aggressive foreign policy and constituted the war party in the period 1792–1793, when revolutionary France initiated a long series of revolutionary wars with other European powers. Brissot proposed an ambitious military plan to spread the Revolution internationally, one thatNapoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

later pursued aggressively. Brissot called on the National Convention to dominate Europe by conquering the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

with a goal of creating a protective ring of satellite republics in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

by 1795. The Girondins also called for war against Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, arguing it would rally patriots around the Revolution, liberate oppressed peoples from despotism, and test the loyalty of King Louis XVI.

Montagnards versus Girondins

Girondins at first dominated the Jacobin Club, where Brissot's influence had not yet been ousted by

Girondins at first dominated the Jacobin Club, where Brissot's influence had not yet been ousted by Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

and they did not hesitate to use this advantage to stir up popular passion and intimidate those who sought to stay the progress of the Revolution. They compelled the king in 1792 to choose a ministry composed of their partisans, among them Roland, Charles François Dumouriez, Étienne Clavière and Joseph Marie Servan de Gerbey

Joseph Marie Servan de Gerbey (14 February 1741 – 10 May 1808) was a French general. During the Revolution he served twice as Minister of War and briefly led the '' Army of the Western Pyrenees''. His surname is one of the names inscribed under ...

; and they forced a declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

against Habsburg Austria The term Habsburg Austria may refer to the lands ruled by the Austrian branch of the Habsburgs, or the historical Austria. Depending on the context, it may be defined as:

* The Duchy of Austria, after 1453 the Archduchy of Austria

* The '' Erblande' ...

the same year. In all of this activity, there was no apparent line of cleavage between ''La Gironde'' and The Mountain. Montagnards and Girondins alike were fundamentally opposed to the monarchy; both were democrats as well as republicans; and both were prepared to appeal to force

''Argumentum ad baculum'' ( Latin for "argument to the cudgel" or "appeal to the stick") is the fallacy committed when one makes an appeal to force to bring about the acceptance of a conclusion.John Woods: ''Argumentum ad baculum.'' In: ''Argum ...

in order to realise their ideals. Despite being accused of wanting to weaken the central government ("federalism"), the Girondins desired as little as the Montagnards to break up the unity of France. From the first, the leaders of the two parties stood in avowed opposition, in the Jacobin Club as in the Assembly.

Temperament largely accounts for the dividing line between the parties. The Girondins were doctrinaires and theorists rather than men of action. They initially encouraged armed petitions, but then were dismayed when this led to the ''émeute'' (riot) of 20 June 1792. Jean-Marie Roland was typical of their spirit, turning the Ministry of the Exterior into a publishing office for tracts on civic virtues while riotous mobs were burning the châteaux unchecked in the provinces. Girondins did not share the ferocious fanaticism or the ruthless opportunism of the future Montagnard organisers of the Reign of Terror. As the Revolution developed, the Girondins often found themselves opposing its results; the overthrow of the monarchy on 10 August 1792 and the September Massacres of 1792 occurred while they still nominally controlled the government, but the Girondins tried to distance themselves from the results of the September Massacres.

When the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

first met on 22 September 1792, the core of like-minded deputies from the Gironde expanded as Jean-Baptiste Boyer-Fonfrède

Jean-Baptiste Boyer-Fonfrède (; 1760 - 31 October 1793) was a French Girondin politician.

A deputy to the National Convention from his native city, Bordeaux, he voted for the death of Louis XVI, denounced the September Massacres and accused Je ...

, Jacques Lacaze and François Bergoeing joined five of the six stalwarts of the Legislative Assembly (Jean Jay, the Protestant pastor, drifted toward the Montagnard faction). Their numbers were increased by the return to national politics by former National Constituent Assembly deputies such as Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne

Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne (; 14 November 1743 – 5 December 1793) was a leader of the French Protestants and a moderate French revolutionary.

Biography

Jean-Paul Rabaut was born in 1743 in Nîmes, in the department of Gard, the son of Paul ...

, Pétion and Kervélégan, as well as some newcomers as the writer Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

and popular journalist Jean Louis Carra.

Decline and fall

The Girondins proposed suspending the king and summoning of the National Convention, but they agreed not to overthrow the monarchy untilLouis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

became impervious to their counsels. Once the king was overthrown in 1792 and a republic was established, they were anxious to stop the revolutionary movement that they had helped to set in motion. Girondins and historian Pierre Claude François Daunou argues in his ''Mémoires'' that the Girondins were too cultivated and too polished to retain their popularity for long in times of disturbance, and so they were more inclined to work for the establishment of order, which would mean the guarantee of their own power. The Girondins, who had been the radicals of the Legislative Assembly (1791–1792), became the conservatives of the Convention (1792–1795).

The Revolution failed to deliver the immediate gains that had been promised and this made it difficult for the Girondins to draw it to a close easily in the minds of the public. Moreover, the ''Septembriseurs'' (the supporters of the September Massacres such as Robespierre, Danton, Marat and their lesser allies) realised that not only their influence but their safety depended on keeping the Revolution alive. Robespierre, who hated the Girondins, had proposed to include them in the proscription lists of September 1792: The Mountain Club to a man who desired their overthrow. A group including some Girondins prepared a draft constitution known as the Girondin constitutional project, which was presented to the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

in early 1793. Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

was one of the signers of this proposal.

The crisis came in March 1793. The Girondins, who had a majority in the Convention, controlled the executive council and filled the ministries, believed themselves invincible. Their orators had no serious rivals in the hostile camp—their system was established in the purest reason, but the Montagnards made up for what they lacked in talent or in numbers through their boldness and fanatical energy. This was especially fruitful since uncommitted delegates accounted for almost half the total number, even though the Jacobins and Brissotins formed the largest groups. The more radical rhetoric of the Jacobins attracted the support of the revolutionary Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defende ...

, the Revolutionary Sections (mass assemblies in districts) and the National Guard of Paris and they had gained control of the Jacobin club, where Brissot, absorbed in departmental work, had been superseded by Robespierre. At the trial of Louis XVI in 1792, most Girondins had voted for the "appeal to the people" and so laid themselves open to the charge of "royalism". They denounced the domination of Paris and summoned provincial levies to their aid and so fell under suspicion of "federalism" as on September 25, 1792. They strengthened the revolutionary Commune by first decreeing its abolition but withdrawing the decree at the first sign of popular opposition.

In the suspicious temper of the times, their vacillation was fatal. Marat never ceased his denunciations of the faction by which France was being betrayed to her ruin and his cry of ''Nous sommes trahis!'' ("We are betrayed!") was echoed from group to group in the streets of Paris. The growing hostility of Paris to the Girondins received a fateful demonstration by the election on 15 February 1793 of the bitter ex-Girondin Jean-Nicolas Pache

Jean-Nicolas Pache (, 5 May 1746 – 18 November 1823) was a French politician, a Jacobin who served as Minister of War from October 1792 and Mayor of Paris from February 1793 to May 1794.

Biography

Pache was born in Verdun, but grew up in Par ...

to the mayoralty. Pache had twice been minister of war in the Girondins government, but his incompetence had laid him open to strong criticism and on 4 February 1793 he had been replaced as minister of war by a vote of the Convention. This was enough to secure him the votes of the Paris electors when he was elected mayor ten days later. The Mountain was strengthened by the accession of a significant ally whose one idea was to use his new power to avenge himself on his former colleagues. Mayor Pache, with ''procureur'' of the Commune Pierre Gaspard Chaumette

Pierre Gaspard Anaxagore Chaumette (24 May 1763 – 13 April 1794) was a French politician of the Revolutionary period who served as the president of the Paris Commune and played a leading role in the establishment of the Reign of Terror. H ...

and deputy ''procureur'' Jacques René Hébert

Ancient and noble French family names, Jacques, Jacq, or James are believed to originate from the Middle Ages in the historic northwest Brittany region in France, and have since spread around the world over the centuries. To date, there are ove ...

, controlled the armed militias of the 48 revolutionary Sections of Paris and prepared to turn this weapon against the Convention. The abortive ''émeute'' of 10 March warned the Girondins of their danger and they responded with defensive moves. They unintentionally increased the prestige of their most vocal and bitter critic Marat by prosecuting him before the Revolutionary Tribunal, where his acquittal in April 1793 was a foregone conclusion. The Commission of Twelve was appointed of on 24 May, including the arrest of Varlat and Hébert and other precautionary measures. The ominous threat by Girondin leader Maximin Isnard

Maximin Isnard (; 16 November 1755 Grasse, Alpes-Maritimes – 12 March 1825 Grasse), French revolutionary, was a dealer in perfumery at Draguignan when he was elected deputy for the ''département'' of the Var to the Legislative Assembly, where ...

, uttered on 25 May, to "march France upon Paris" was instead met by Paris marching hastily upon the Convention. The Girondin role in the government was undermined by the popular uprisings of 27 and 31 May and finally on 2 June 1793, when François Hanriot, head of the Paris National Guards, purged the Convention of the Girondins (see Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793).

Reign of Terror

A list drawn up by the Commandant-General of the Parisian National Guard François Hanriot (with help from Marat) and endorsed by a decree of the intimidated Convention, included 22 Girondin deputies and 10 of the 12 members of the Commission of Twelve, who were ordered to be detained at their lodgings "under the safeguard of the people". Some submitted, among them Gensonné, Guadet, Vergniaud, Pétion, Birotteau and Boyer-Fonfrède. Others, including Brissot, Louvet, Buzot, Lasource, Grangeneuve, Larivière and François Bergoeing, escaped from Paris and, joined later by Guadet, Pétion and Birotteau, set to work to organise a movement of the provinces against the capital. This attempt to stir up civil war made the wavering and frightened Convention suddenly determined. On 13 June 1793, it voted that the city of Paris deserved well of the country and ordered the imprisonment of the detained deputies, the filling up of their places in the Assembly by their ''suppléants'' and the initiation of vigorous measures against the movement in the provinces. The assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday on 13 July 1793 only served to increase the unpopularity of the Girondins and seal their fate. The excuse for the Terror that followed was the imminent peril of France, menaced on the east by the advance of the armies of the First Coalition (Austria, Prussia and Great Britain) on the west by the RoyalistRevolt in the Vendée

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

and the need for preventing at all costs the outbreak of another civil war. On 28 July 1793, a decree of the Convention proscribed 21 deputies, five of whom were from the Gironde, as traitors and enemies of their country ( Charles-Louis Antiboul, Boilleau the younger, Boyer-Fonfrêde, Brissot, Carra, Gaspard-Séverin Duchastel, the younger Ducos, Dufriche de Valazé, Jean Duprat, Fauchet, Gardien, Gensonné, Lacaze, Lasource, Claude Romain Lauze de Perret, Lehardi, Benoît Lesterpt-Beauvais, the elder Minvielle, the Marquis de Sillery, Vergniaud and Louis-François-Sébastien Viger). Those were sent to trial. Another 39 were included in the final ''acte d'accusation'', accepted by the Convention on 24 October 1793, which stated the crimes for which they were to be tried as their perfidious ambition, their hatred of Paris, their "federalism" and above all their responsibility for the attempt of their escaped colleagues to provoke civil war.

1793 trial of Girondins

The trial of the 22 began before the Revolutionary Tribunal on 24 October 1793. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. On 31 October, they were borne to the guillotine. It took 36 minutes to decapitate all of them, including Charles Éléonor Dufriche de Valazé, who had committed suicide the previous day upon hearing the sentence he was given.

Of those who escaped to the provinces, after wandering about singly or in groups most were either captured and executed or committed suicide. They included Barbaroux, Buzot,

The trial of the 22 began before the Revolutionary Tribunal on 24 October 1793. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. On 31 October, they were borne to the guillotine. It took 36 minutes to decapitate all of them, including Charles Éléonor Dufriche de Valazé, who had committed suicide the previous day upon hearing the sentence he was given.

Of those who escaped to the provinces, after wandering about singly or in groups most were either captured and executed or committed suicide. They included Barbaroux, Buzot, Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal p ...

, Grangeneuve, Guadet, Kersaint, Pétion, Rabaut de Saint-Etienne and Rebecqui. Roland killed himself at Rouen on 15 November 1793, a week after the execution of his wife. A very few escaped, including Jean-Baptiste Louvet de Couvrai, whose ''Mémoires'' give a detailed picture of the sufferings of the fugitives.

Girondins as martyrs

The survivors of the party made an effort to re-enter the Convention after the fall of Robespierre on 27 July 1794, but it was not until 5 March 1795 that they were formally re-instated forming the Council of Five Hundred under the Directory. On 3 October of that same year (11Vendémiaire

Vendémiaire () was the first month in the French Republican calendar. The month was named after the Occitan word ''vendemiaire'' (grape harvester).

Vendémiaire was the first month of the autumn quarter (''mois d'automne''). It started on the ...

, year IV), a solemn ''fête'' in honour of the Girondins, "martyrs of liberty", was celebrated in the Convention.

In her autobiography, Madame Roland reshapes her historical image by stressing the popular connection between sacrifice and female virtue. Her ''Mémoires de Madame Roland'' (1795) was written from prison where she was held as a Girondin sympathizer. It covers her work for the Girondins while her husband Jean-Marie Roland was Interior Minister. The book echoes such popular novels as Rousseau's ''Julie or the New Héloise'' by linking her feminine virtue and motherhood to her sacrifice in a cycle of suffering and consolation. Roland says her mother's death was the impetus for her "odyssey from virtuous daughter to revolutionary heroine" as it introduced her to death and sacrifice – with the ultimate sacrifice of her own life for her political beliefs. She helped her husband escape, but she was executed on 8 November 1793. A week later he committed suicide.

A monument to the Girondins was erected in Bordeaux between 1893 and 1902 dedicated to the memory of the Girondin deputies who were victims of the Terror. The vagueness of who actually made up the Girondins led to the monument not having any names inscribed on it until 1989. Even then, the deputies to the Convention who were memorialized were only those hailing from the Gironde department, omitting notable people like Brissot and Madame Roland.

Ideology

The words Girondin and Montagnard are defined as political groups―more specific definitions are the subject of theorizing by historians. The two words were much tossed about by partisans with various understandings of what they were intended to represent. The two groups lacked formal political structures, and the differences between them have never been satisfactorily explained. It has been suggested that the word Girondin as a useful term be abandoned. Influenced byclassical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, e ...

and the concepts of democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

, human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

and Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

's separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typi ...

, the Girondins initially supported the constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, but after the Flight to Varennes in which Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

tried to flee Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in order to start a counter-revolution the Girondins became mostly republicans, with a royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

minority. Like the Jacobins, they were also influenced by the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

.

In its early times of government, the Gironde supported a free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

- opposing price controls on goods (e.g., a 1793 maximum on grain prices), supported by a constitutional right

A constitutional right can be a prerogative or a duty, a power or a restraint of power, recognized and established by a sovereign state or union of states. Constitutional rights may be expressly stipulated in a national constitution, or they may ...

to public assistance for the poor and public education. With Brissot, they advocated exporting the Revolution through aggressive foreign policies including war against the surrounding European monarchies. The Girondins were also one of the first supporters of abolitionism in France with Brissot leading the anti-slavery Society of the Friends of the Blacks. Certain Girondins such as Condorcet supported women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

and political equality.

They sat to the left of the centrist Feuillants, but later sat on the right of the National Assembly after the neutralization of the Feuillants. They were the principal conservative political party in France at the time and opposed the radical course of the revolution, leading to the Reign of Terror. Generally, historians divide the Convention into the left-wing Jacobin Montagnards, the centrist The Plain and the right-wing Girondins.

The Girondins supported democratic reform

Democratization, or democratisation, is the transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction. It may be a hybrid regime in transition from an authoritarian regime to a full ...

, secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a si ...

and a strong legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

at the expense of a weaker executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive di ...

and judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

as opposed to the authoritarian left-wing Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

*Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of th ...

, who supported public acknowledgement of a Supreme Being and a strong executive.Jonathan Israel (2015). ''Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre''.

Prominent members

* Jacques Pierre Brissot (leader) * Jean-Marie Roland * Madame Roland *Maximin Isnard

Maximin Isnard (; 16 November 1755 Grasse, Alpes-Maritimes – 12 March 1825 Grasse), French revolutionary, was a dealer in perfumery at Draguignan when he was elected deputy for the ''département'' of the Var to the Legislative Assembly, where ...

* Jacques Guillaume Thouret

Jacques Guillaume Thouret (30 April 1746 – 22 April 1794) was a French Girondin revolutionary, lawyer, president of the National Constituent Assembly and victim of the guillotine.

Biography

Born at Pont-l'Évêque, Calvados ( Normandy) t ...

* Jean Baptiste Treilhard

Jean-Baptiste Treilhard (; 3 January 1742 – 1 December 1810) was an important French statesman of the revolutionary period. He passed through the troubled times of the Republic and Empire with great political savvy, playing a decisive role at ...

* Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud

* Armand Gensonné

Armand Gensonné (, 10 August 175831 October 1793) was a French politician.

The son of a military surgeon, he was born in Bordeaux, Gascony, and studied Law before the outbreak of the French Revolution, becoming lawyer of the ''parlement'' of ...

* Marquis de Condorcet

* Pierre Claude François Daunou

* Marguerite-Élie Guadet

Marguerite-Élie Guadet (, 20 July 1758 – 19 June 1794) was a French political figure of the Revolutionary period.

Rise to prominence

Born in Saint-Émilion, Gironde, Aquitaine, he had already gained a reputation as a lawyer in Bordeaux by ...

* Jacques Claude Beugnot

Jacques Claude, comte Beugnot (25 July 1761 – 24 June 1835) was a French politician before, during, and after the French Revolution. His son Auguste Arthur Beugnot was an historian and scholar.

Biography

Revolution

Born at Bar-sur-Aube (A ...

* Louis Gustave le Doulcet

* Claude Fauchet

* François Buzot

François Nicolas Léonard Buzot (1 March 176018 June 1794) was a French politician and leader of the French Revolution.

Biography

Early life

Born at Évreux, Eure, he studied Law, and, at the outbreak of the Revolution was a lawyer in his hom ...

* Charles Jean Marie Barbaroux

Charles Jean Marie Barbaroux (6 March 1767 – 25 June 1794) was a French politician of the Revolutionary period and Freemason.

Biography

Early career

Born in Marseille, Barbaroux was educated at first by the local Oratorians, then studied l ...

* François Aubry

* Charles-Louis Antiboul

* Léger-Félicité Sonthonax

* Jérôme Pétion

Electoral results

See also

*Historiography of the French Revolution

The historiography of the French Revolution stretches back over two hundred years, as commentators and historians have used a vast array of primary sources to explain the origins of the Revolution, and its meaning and its impact. By the year 2000, ...

* Liberalism and radicalism in France

References

Citations

General Bibliography

* * * * * * ; Attribution * The article was originally a copy of the 1911 article.Further reading

* Brace, Richard Munthe. "General Dumouriez and the Girondins 1792–1793", ''American Historical Review'' (1951) 56#3 pp. 493–509. . * de Luna, Frederick A. "The 'Girondins' Were Girondins, After All", ''French Historical Studies'' (1988) 15: 506-18. . * DiPadova, Theodore A. "The Girondins and the Question of Revolutionary Government", ''French Historical Studies'' (1976) 9#3 pp. 432–450 . * Ellery, Eloise. ''Brissot De Warville: A Study in the History of the French Revolution'' (1915excerpt and text search

* François Furet and Mona Ozouf. eds. ''La Gironde et les Girondins''. Paris: éditions Payot, 1991. * Higonnet, Patrice. "The Social and Cultural Antecedents of Revolutionary Discontinuity: Montagnards and Girondins", ''English Historical Review'' (1985): 100#396 pp. 513–544 . * Thomas Lalevée,

National Pride and Republican grandezza: Brissot's New Language for International Politics in the French Revolution

, ''French History and Civilisation'' (Vol. 6), 2015, pp. 66–82. * Lamartine, Alphonse de. ''History of the Girondists, Volume I: Personal Memoirs of the Patriots of the French Revolution'' (1847

online free in Kindle edition

Volume 3

* Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Anne Hildreth, and Alan B. Spitzer. "Was There a Girondist Faction in the National Convention, 1792–1793?" ''French Historical Studies'' (1988) 11#4 pp.: 519-36. . * Linton, Marisa, ''Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution'' (Oxford University Press, 2013). * Loomis, Stanley, ''Paris in the Terror''. (1964). * Patrick, Alison. "Political Divisions in the French National Convention, 1792–93". ''Journal of Modern History'' (Dec. 1969) 41#4, pp.: 422–474. ; rejects Sydenham's argument & says Girondins were a real faction. * Patrick, Alison. ''The Men of the First French Republic: Political Alignments in the National Convention of 1792'' (1972), comprehensive study of the group's role. * Scott, Samuel F., and Barry Rothaus. ''Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution 1789–1799'' (1985) Vol. 1 pp. 433–3

online

* Sutherland, D. M. G. ''France 1789–1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution'' (2nd ed., 2003) ch. 5. * Sydenham, Michael J. "The Montagnards and Their Opponents: Some Considerations on a Recent Reassessment of the Conflicts in the French National Convention, 1792–93", ''Journal of Modern History'' (1971) 43#2 pp. 287–293 ; argues that the Girondins faction was mostly a myth created by Jacobins. * Whaley, Leigh Ann. ''Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution''. Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

External links

{{Authority control 1792 establishments in France 1793 disestablishments in France Abolitionist organizations Conservative liberal parties France 1791 Defunct political parties in France French National Convention Groups of the French Revolution Liberal parties in France Political parties established in 1792 Political parties disestablished in 1793 Monarchist parties in France