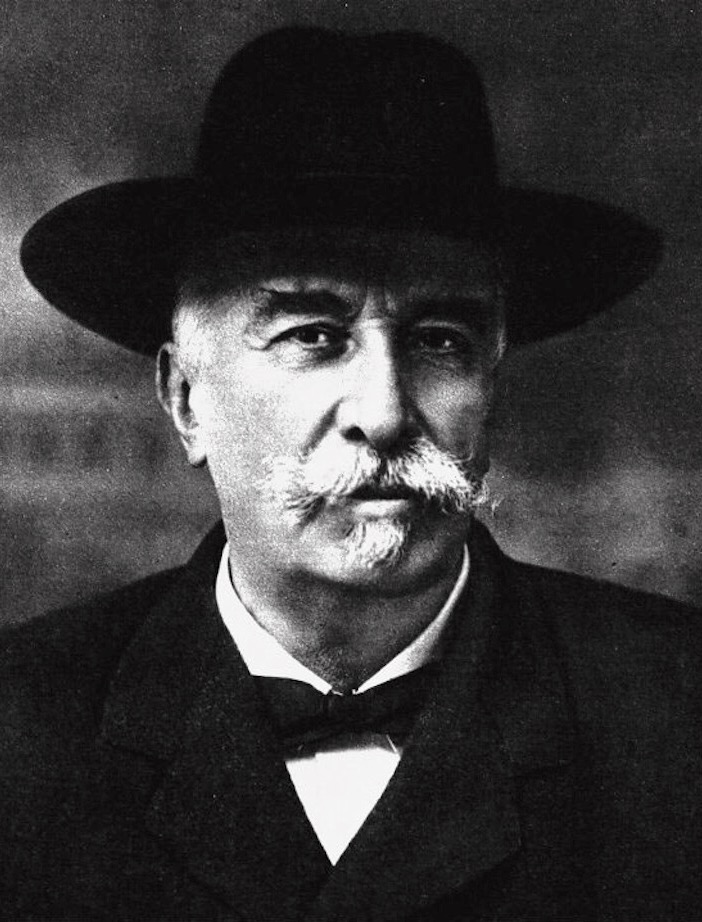

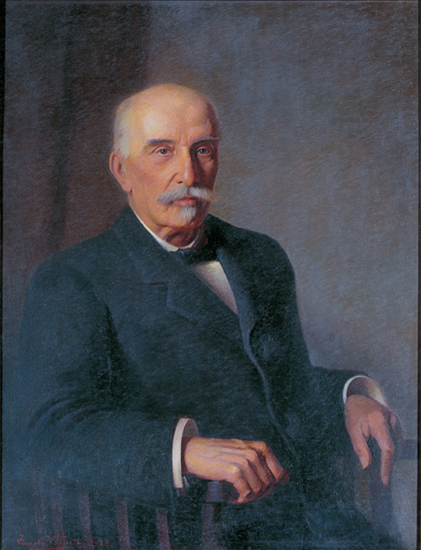

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the

Prime Minister of Italy

The Prime Minister of Italy, officially the President of the Council of Ministers ( it, link=no, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is ...

five times between 1892 and 1921. After

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, he is the

second-longest serving Prime Minister in

Italian history

The history of Italy covers the ancient period, the Middle Ages, and the modern era. Since classical antiquity, ancient Etruscans, various Italic peoples (such as the Latins, Samnites, and Umbri), Celts, '' Magna Graecia'' colonists, and oth ...

. A prominent leader of the

Historical Left

The Left group ( it, Sinistra), later called Historical Left ( it, Sinistra storica) by historians to distinguish it from the left-wing groups of the 20th century, was a liberal and reformist parliamentary group in Italy during the second half of ...

and the

Liberal Union, he is widely considered one of the most powerful and important politicians in Italian history; due to his dominant position in

Italian politics

The politics of Italy are conducted through a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system. Italy has been a democratic republic since 2 June 1946, when the monarchy was abolished by popular referendum and a constituent assembly was electe ...

, Giolitti was accused by critics of being an

authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

leader and a parliamentary

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

.

Giolitti was a master in the political art of ''

trasformismo

''Trasformismo'' is the method of making a flexible centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the political left and the political right in Italian politics after the Italian unification and before the rise of Benito Mussoli ...

'', the method of making a flexible,

centrist

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to Left-w ...

coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the Left and the Right in Italian politics after the unification. Under his influence, the Liberals did not develop as a structured party and were a series of informal personal groupings with no formal links to political constituencies. The period between the start of the 20th century and the start of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when he was Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior from 1901 to 1914, with only brief interruptions, is often referred to as the "Giolittian Era".

[Barański & West, ]

The Cambridge Companion to Modern Italian Culture

', p. 44[Killinger, ]

The History of Italy

', p. 127–28

A centrist

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

,

[ with strong ethical concerns, Giolitti's periods in office were notable for the passage of a wide range of progressive ]social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

s which improved the living standards of ordinary Italians, together with the enactment of several policies of government intervention.[Sarti, ]

Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present

', pp. 46–48 Besides putting in place several tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and polic ...

, subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

, and government projects, Giolitti also nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

the private telephone and railroad operators. Liberal proponents of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

criticized the "Giolittian System", although Giolitti himself saw the development of the national economy as essential in the production of wealth.

The primary focus of Giolittian politics was to rule from the centre with slight and well controlled fluctuations between conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

and progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tec ...

, trying to preserve the institutions and the existing social order.[ ]Right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

critics like Luigi Albertini

Luigi Albertini (19 October 1871–29 December 1941) was an influential Italian newspaper editor, member of the Parliament, and historian of the First World War.

As editor of one of Italy's best-known newspapers, ''Corriere della Sera'' of Mila ...

considered him a ''socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

'' due to the courting of socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

votes in parliament in exchange for political favours, while left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

critics like Gaetano Salvemini

Gaetano Salvemini (; 8 September 1873 – 6 September 1957) was an Italian Socialist and antifascist politician, historian and writer. Born in a family of modest means, he became an acclaimed historian both in Italy and abroad, particularly in ...

accused him of being a corrupt politician and of winning elections with the support of criminals.[ Nonetheless, his highly complex legacy continues to stimulate intense debate among writers and historians.

]

Early life

Giolitti was born at Mondovì, in

Giolitti was born at Mondovì, in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. His father Giovenale Giolitti had been working in the avvocatura dei poveri, an office assisting poor citizens in both civil and criminal cases. He died in 1843, a year after Giovanni was born. The family moved in the home of his mother Enrichetta Plochiù in Turin.

His mother taught him to read and write; his education in the gymnasium San Francesco da Paola of Turin was marked by poor discipline and little commitment to study. He did not like mathematics and the study of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

grammar, preferring the history and reading the novels of Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

and Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honoré Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-François Balssa, père d'Honoré de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Comédie humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

. At sixteen he entered the University of Turin

The University of Turin (Italian: ''Università degli Studi di Torino'', UNITO) is a public research university in the city of Turin, in the Piedmont region of Italy. It is one of the oldest universities in Europe and continues to play an impo ...

and, after three years, he earned a law degree in 1860.[De Grand, ''The Hunchback's Tailor'']

p. 12

/ref>

His uncle was a member of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

and a close friend of Michelangelo Castelli, the secretary of Camillo Benso di Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (, 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as Cavour ( , ), was an Italian politician, businessman, economist and noble, and a leading figure in the movement t ...

; however, Giolitti did not appear particularly interested in the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

and differently to many of his fellow students, he did not enlist to fight in the Italian Second War of Independence.

Career in the public administration

Giolitti pursued a career in public administration in the Ministry of Grace and Justice. That choice prevented him from participating in the decisive battles of the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

(the unification of Italy), for which his temperament was not suited anyway, but this lack of military experience would be held against him as long as the Risorgimento generation was active in politics.[Sarti, ''Italy: a Reference Guide From the Renaissance to the Present'']

pp. 313-14

/ref>

In 1869, he moved to the Ministry of Finance, becoming a high official and working along with important members of the ruling Right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of Liberty, freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convent ...

, like Quintino Sella

Quintino Sella (; 7 July 1827 – 14 March 1884) was an Italian politician, economist and mountaineer.

Biography

Sella was born at Sella di Mosso, in the Province of Biella.

After studying engineering at Turin, he was sent in 1843 to study mi ...

and Marco Minghetti

Marco Minghetti (18 November 1818 – 10 December 1886) was an Italian economist and statesman.

Biography

Minghetti was born at Bologna, then part of the Papal States.

He signed the petition to the Papal conclave, 1846, urging the electio ...

. In the same year he married Rosa Sobrero, the niece of Ascanio Sobrero, a famous chemist, who discovered nitroglycerine

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating ...

.

In 1877, Giolitti was appointed to the Court of Audit A Court of Audit or Court of Accounts is a Supreme audit institution, i.e. a government institution performing financial and/or legal audit (i.e. Statutory audit or External audit) on the executive branch of power.

See also

*Most of those in ...

and in 1882 to the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

.

Beginnings of the political career

At the 1882 Italian general election he was elected to the

At the 1882 Italian general election he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

(the lower house

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

) for the Historical Left

The Left group ( it, Sinistra), later called Historical Left ( it, Sinistra storica) by historians to distinguish it from the left-wing groups of the 20th century, was a liberal and reformist parliamentary group in Italy during the second half of ...

.[ This election was a great victory for the ruling Left of Agostino Depretis, which won 289 seats out of 508.

As deputy he chiefly acquired prominence by attacks on ]Agostino Magliani

Agostino Magliani (23 July 182420 February 1891), Italian financier, was a native of Laurino, near Salerno.

He studied at Naples, and a book on the philosophy of law based on Liberal principles won for him a post in the Neapolitan treasury. He ...

, Treasury Minister in the cabinet of Depretis.

Following Depretis's death on 29 July 1887 Francesco Crispi, a notable politician and patriot, became the leader of the Left group and was also appointed Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

by King Umberto I

Umberto I ( it, Umberto Rainerio Carlo Emanuele Giovanni Maria Ferdinando Eugenio di Savoia; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his assassination on 29 July 1900.

Umberto's reign saw Italy attempt colo ...

.

On 9 March 1889 Giolitti was selected by Crispi as new Minister of Treasury and Finance. But in October 1890, Giolitti resigned from his office due to contrasts with Crispi's colonial policy. In fact few weeks before, the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II

, spoken = ; ''djānhoi'', lit. ''"O steemedroyal"''

, alternative = ; ''getochu'', lit. ''"Our master"'' (pl.)

Menelik II ( gez, ዳግማዊ ምኒልክ ; horse name Abba Dagnew ( Amharic: አባ ዳኘው ''abba daññäw''); 17 ...

had contested the Italian text of the Wuchale Treaty, signed by Crispi, stating that it did not oblige Ethiopia to be an Italian protectorate. Menelik informed the foreign press and the scandal erupted.

After the fall of the government led by the new Prime Minister Antonio Starabba di Rudinì

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

in May 1892, Giolitti, with the help of a court clique, received from the King the task of forming a new cabinet.

First term as Prime Minister

Giolitti's first term as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

(1892–1893) was marked by misfortune and misgovernment. The building crisis and the commercial rupture with France had impaired the situation of the state banks, of which one, the '' Banca Romana'', had been further undermined by misadministration.

Banca Romana scandal

The ''Banca Romana'' had loaned large sums to property developers but was left with huge liabilities when the real estate bubble collapsed in 1887.

The ''Banca Romana'' had loaned large sums to property developers but was left with huge liabilities when the real estate bubble collapsed in 1887.[Alfredo Gigliobianco and Claire Giordano]

Economic Theory and Banking Regulation: The Italian Case (1861-1930s)

Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers), Nr. 5, November 2010 Then Prime Minister Francesco Crispi and his Treasury Minister Giolitti knew of the 1889 government inspection report, but feared that publicity might undermine public confidence and suppressed the report.[Seton-Watson, ''Italy from Liberalism to Fascism'', pp. 154-56]

The Bank Act of August 1893 liquidated the ''Banca Romana'' and reformed the whole system of note issue, restricting the privilege to the new '' Banca d'Italia'' – mandated to liquidate the ''Banca Romana'' – and to the ''Banco di Napoli

Banco di Napoli S.p.A., among the oldest banks in the world, was an Italian banking subsidiary of Intesa Sanpaolo group, as one of the 6 retail brands other than "Intesa Sanpaolo". It was acquired by the Italian banking group Sanpaolo IMI (the p ...

'' and the ''Banco di Sicilia

Banco di Sicilia was an Italian bank based in Palermo, Sicily. It was a subsidiary of UniCredit but absorbed into the parent company in 2010.

History

It was founded as ''Banco Regio dei Reali Domini al di là del Faro'' in 1849 and was renamed in ...

'', and providing for stricter state control.[Pohl & Freitag, Handbook on the history of European banks'']

p. 564

/ref> The new law failed to effect an improvement. Moreover, he irritated public opinion by raising to senatorial rank the governor of the ''Banca Romana'', Bernardo Tanlongo, whose irregular practices had become a byword, which would have given him immunity from prosecution.[Duggan, ''The Force of Destiny'']

p. 340

/ref> The senate declined to admit Tanlongo, whom Giolitti, in consequence of an intervention in parliament upon the condition of the Banca Romana, was obliged to arrest and prosecute. During the prosecution Giolitti abused his position as premier to abstract documents bearing on the case.

Fasci Siciliani

Another main problem that Giolitti had to face during his first term as Prime Minister were the Fasci Siciliani

The Fasci Siciliani , short for Fasci Siciliani dei Lavoratori (Sicilian Workers Leagues), were a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration, which arose in Sicily in the years between 1889 and 1894. The Fasci gained the support o ...

, a popular movement of democratic and socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

inspiration, which arose in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

in the years between 1889 and 1894. The Fasci gained the support of the poorest and most exploited classes of the island by channeling their frustration and discontent into a coherent programme based on the establishment of new rights. Consisting of a jumble of traditionalist sentiment, religiosity, and socialist consciousness, the movement reached its apex in the summer of 1893, when new conditions were presented to the landowners and mine owners of Sicily concerning the renewal of sharecropping and rental contracts.

Upon the rejection of these conditions, there was an outburst of strikes that rapidly spread throughout the island, and was marked by violent social conflict, almost rising to the point of insurrection. The leaders of the movement were not able to keep the situation from getting out of control. The proprietors and landowners asked the government to intervene. Giovanni Giolitti tried to put a halt to the manifestations and protests of the Fasci Siciliani, his measures were relatively mild. On November 24, Giolitti officially resigned as Prime Minister. In the three weeks of uncertainty before Crispi formed a government on 15 December 1893, the rapid spread of violence drove many local authorities to defy Giolitti's ban on the use of firearms.

In December 1893, 92 peasants lost their lives in clashes with the police and army. Government buildings were burned along with flour mills and bakeries that refused to lower their prices when taxes were lowered or abolished.

Resignation

Simultaneously a parliamentary commission of inquiry investigated the condition of the state banks. Its report, though acquitting Giolitti of personal dishonesty, proved disastrous to his political position, and the ensuing Banca Romana scandal

The ''Banca Romana'' scandal surfaced in January 1893 in Italy over the bankruptcy of the ''Banca Romana'', one of the six national banks authorised at the time to issue currency. The scandal was the first of many Italian corruption scandals, and ...

obliged him to resign. His fall left the finances of the state disorganized, the pensions fund depleted, diplomatic relations with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

strained in consequence of the massacre of Italian workmen at Aigues-Mortes, and a state of revolt in the Lunigiana

The Lunigiana () is a historical territory of Italy, which today falls within the provinces of Massa Carrara, Tuscany, and La Spezia, Liguria. Its borders derive from the ancient Roman settlement, later the medieval diocese of Luni, which no long ...

and by the Fasci Siciliani

The Fasci Siciliani , short for Fasci Siciliani dei Lavoratori (Sicilian Workers Leagues), were a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration, which arose in Sicily in the years between 1889 and 1894. The Fasci gained the support o ...

in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, which he had proved impotent to suppress. Despite the heavy pressure from the King, the army and conservative circles in Rome, Giolitti neither treated strikes – which were not illegal – as a crime, nor dissolved the Fasci, nor authorised the use of firearms against popular demonstrations.[De Grand, ]

The Hunchback's Tailor

', pp. 47-48 His policy was "to allow these economic struggles to resolve themselves through amelioration of the condition of the workers" and not to interfere in the process.[Seton-Watson, ''Italy from Liberalism to Fascism'', pp. 162-63]

Impeachment and comeback

After his resignation Giolitti was impeached for abuse of power as minister, but the Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ...

quashed the impeachment by denying the competence of the ordinary tribunals to judge ministerial acts.

For several years he was compelled to play a passive part, having lost all credit. But by keeping in the background and giving public opinion time to forget his past, as well as by parliamentary intrigue, he gradually regained much of his former influence.

Moreover, Giolitti made capital of the Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

agitation and of the repression to which other statesmen resorted, and gave the agitators to understand that were he premier would remain neutral in labour conflicts. Thus he gained their favour, and on the fall of the cabinet led by General Luigi Pelloux

Luigi Gerolamo Pelloux ( La Roche-sur-Foron, 1 March 1839 – Bordighera, 26 October 1924) was an Italian general and politician, born of parents who retained their Italian nationality when Savoy was annexed to France. He was the Prime Minister o ...

in 1900, he made his comeback after eight years, openly opposing the authoritarian new public safety laws.[Clark, ''Modern Italy: 1871 to the present'']

p. 141-42

/ref>

Due to a left-ward shift in parliamentary liberalism at the general election in June, after the reactionary crisis of 1898–1900, he dominated Italian politics until World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.[Duggan]

''The Force of Destiny''

pp. 362-63

Between 1901 and 1903 he was appointed Italian Minister of the Interior

The Minister of the Interior (Italian: ''Ministro dell'Interno'') in Italy is one of the most important positions in the Italian Council of Ministers and leads the Ministry of the Interior. The current Minister is prefect Matteo Piantedosi, ...

by Prime Minister Giuseppe Zanardelli

Giuseppe Zanardelli (29 October 1826 26 December 1903) was an Italian jurist and political figure. He served as the Prime Minister of Italy from 15 February 1901 to 3 November 1903. An eloquent orator, he was also a Grand Master freemason. Zan ...

, but critics accused Giolitti of being the ''de facto'' Prime Minister, due to Zanardelli's age.[

]

Second term as Prime Minister

On 3 November 1903 Giovanni Giolitti was appointed Prime Minister by King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

.

Relations with the Socialists

During his second term as head of the government he courted the left and labour unions with social legislation, including subsidies for low-income housing, preferential government contracts for worker cooperatives, and old age and disability pensions.[ Giolitti tried to sign an alliance with the ]Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

, which was growing so fast in the popular vote, and became a friend of the Socialist leader Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 – 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and participa ...

. Giolitti would have likes to have Turati as minister in his cabinets, but the Socialist leader always refused, due to the opposition of the left-wing of his party.

Moreover, Giolitti, differently from his predecessors like Francesco Crispi, strongly opposed the repression of labour union strikes. According to him, the government had to act as a mediator between entrepreneurs and workers. These concepts, which today may seem obvious, they were considered revolutionary at the time. The conservatives harshly criticized him; according to them this policy was a complete failure that could create fear and disorder.

Resignation

However, Giolitti too, had to resort to strong measures in repressing some serious disorders in various parts of Italy, and thus he lost the favour of the Socialists. In March 1905, feeling himself no longer secure, he resigned, indicating Fortis as his successor. When the leader of the Historical Right, Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il Gio ...

, became premier in February 1906, Giolitti did not openly oppose him, but his followers did.

Third term as Prime Minister

When Sonnino lost his majority in May 1906, Giolitti became Prime Minister once more. His third government was known as the "long ministry" (''lungo ministero'').

Financial policy

In the financial sector the main operation was the conversion of the annuity, with the replacement of fixed-rate government bonds maturing (with coupon of 5%) with others at lower rates (3.75% before and then 3.5%). The conversion of the annuity was conducted with considerable caution and technical expertise: the government, in fact, before undertaking it, requested and obtained the guarantee of numerous banking institutions.

The criticism that the government received by conservatives proved unfounded: the public opinion followed almost fondly the events relating, as the conversion immediately took on the symbolic value of a real and lasting fiscal consolidation and a stable national unification. The resources were used to complete the nationalization of the railways.

The strong economic performance and the careful budget management led to a currency stability; this was also caused by a mass emigration and especially on remittances that Italian migrants sent to their relatives back home. The 1906–1909 triennium is remembered as the time when "the lira was premium on gold".

In the financial sector the main operation was the conversion of the annuity, with the replacement of fixed-rate government bonds maturing (with coupon of 5%) with others at lower rates (3.75% before and then 3.5%). The conversion of the annuity was conducted with considerable caution and technical expertise: the government, in fact, before undertaking it, requested and obtained the guarantee of numerous banking institutions.

The criticism that the government received by conservatives proved unfounded: the public opinion followed almost fondly the events relating, as the conversion immediately took on the symbolic value of a real and lasting fiscal consolidation and a stable national unification. The resources were used to complete the nationalization of the railways.

The strong economic performance and the careful budget management led to a currency stability; this was also caused by a mass emigration and especially on remittances that Italian migrants sent to their relatives back home. The 1906–1909 triennium is remembered as the time when "the lira was premium on gold".

Social policy

Giolitti's government introduced laws to protect women and children workers with new time (12 hours) and age (12 years) limits this law being implemented between 1900 - 1907. On this occasion the Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

deputies voted in favor of the government: it was one of the few times in which a Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

parliamentary group openly supported a "bourgeois government."

The majority also approved special laws for disadvantaged regions of the Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

. Such measures, although they could not even come close to bridging the north-south differences, gave appreciable results. This policy's aim was to improve the economic conditions of the farmers from the south.

1908 Messina earthquake

On 28 December 1908, a strong

On 28 December 1908, a strong earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

of magnitude of 7.1 and a maximum Mercalli intensity scale of XI, hits Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. About ten minutes after the earthquake, the sea on both sides of the Strait suddenly withdrew a 12-meter (39-foot) tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater explo ...

swept in, and three waves struck nearby coasts. It impacted hardest along the Calabrian coast and inundated Reggio Calabria

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label= Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

after the sea had receded 70 meters from the shore. The entire Reggio seafront was destroyed and numbers of people who had gathered there perished. Nearby Villa San Giovanni

Villa San Giovanni is a port city and a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria of Calabria, Italy. In 2010 its population was 13,747 with a decrease of 2.5% until 2016 and in 2020 an increase of 3.7% . It is an important termin ...

was also badly hit. Along the coast between Lazzaro and Pellaro The territory of the municipality of Reggio Calabria and the division and numbering of the districts with Pellaro as 15

Pellaro is the southernmost quarter of the commune of Reggio Calabria, southern Italy. It has approximately 13,000 inhabitant ...

, houses and a railway bridge were washed away. The cities of Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

and Reggio Calabria

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label= Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

were almost completely destroyed and between 75,000 and 200,000 lives were lost.Nicotera

Nicotera ( Calabrian: ; grc, Νικόπτερα, translit=Nikóptera) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Vibo Valentia, Calabria, southern Italy.

History

The origins of Nicòtera lie with the ancient Greek city of Medma, which ...

, where the telegraph lines were still working, but that was not accomplished until midnight at the end of the day. Rail lines in the area had been destroyed, often along with the railway stations.Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

and Queen Elena arrived two days after the earthquake to assist the victims and survivors.Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

and sailors of the Russian and British fleets, search and cleanup were expedited.

1909 election and resignation

In 1909 general election, Giolitti's Left gained 54.4% of votes and 329 seats out of 508.[ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1047 ] Despite the strong victory Giolitti proposed the conservative leader Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il Gio ...

as new Prime Minister. After few months, he withdrew his support to Sonnino's government and supported the moderate Luigi Luzzatti

Luigi Luzzatti (11 March 1841 – 29 March 1927) was an Italian financier, political economist, social philosopher, and jurist. He served as the 20th prime minister of Italy between 1910 and 1911.

Luzzatti came from a wealthy and cultured Jewis ...

as new head of government.

After the premiership

Universal manhood suffrage

During Luzzatti's government the political debate had begun to focus on the enlargement of the right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

. The Socialists, in fact, but also the Radicals and the Republicans, has long demanded the introduction of universal manhood suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

, necessary in a modern liberal democracy. Luzzatti developed a moderate proposal with some requirements under which a person had the right to vote (age, literacy and annual taxes). The government's proposal was of a gradual expansion of the electorate, but without reaching the universal male suffrage.

Giolitti, speaking in the Chamber, declared himself in favor of universal male suffrage, overcoming the impulse to government positions. His aim was to cause Luzzatti's resignation and become Prime Minister again; moreover he want to start a cooperation with the Socialists in the Italian parliamentary system. Furthermore, Giolitti intended to extend his pre-war reforms. Conscripted men were fighting overseas in Libya and so it appeared as a symbol of national unity that they be given the vote.

Giolitti believed that the extension of the franchise would bring more conservative rural voters to the polls as well as drawing votes from grateful socialists.

Many historians considered Giolitti's proposal a mistake. Universal male suffrage, contrary to Giolitti's opinions, would destabilize the entire political establishment: the "mass parties," i.e. Socialist, Popular and later Fascist, were the ones who benefitted from the new electoral system. Giolitti "was convinced that Italy can not grow economically and socially without enlarging the number of those who partecipated ic?in public life."

Sidney Sonnino and the Socialists Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 – 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and participa ...

and Claudio Treves Claudio Treves (24 March 1869 – 11 June 1933) was an Italian politician and journalist.

Life Youth

Claudio Treves was born in Turin into a well off assimilated Jewish family. As a student he participated in the Radical milieu of Turin and, ...

proposed to introduce also female suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, but Giolitti strongly opposed it, considering it too risky, and suggested the introduction of female suffrage only at the local level.

Fourth term as Prime Minister

Although a man of first-class financial ability, great honesty and wide culture, Luzzatti had not the strength of character necessary to lead a government: he showed lack of energy in dealing with opposition and tried to avoid all measures likely to make him unpopular. Furthermore, he never realized that with the chamber, as it was then constituted, he only held office at Giolitti's good pleasure. So on 30 March 1911 Luzzatti resigned from his office and King

Although a man of first-class financial ability, great honesty and wide culture, Luzzatti had not the strength of character necessary to lead a government: he showed lack of energy in dealing with opposition and tried to avoid all measures likely to make him unpopular. Furthermore, he never realized that with the chamber, as it was then constituted, he only held office at Giolitti's good pleasure. So on 30 March 1911 Luzzatti resigned from his office and King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

still gave Giolitti the task to form a new cabinet.

Social policy

During his fourth term, Giolitti tried to seal an alliance with the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

, proposing the universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

, implementing left-wing social policies, introducing the National Insurance Institute, which provided for the nationalization of insurance at the expense of the private sector. Moreover, Giolitti appointed the socialist Alberto Beneduce

Alberto Beneduce (29 May 1877 – 26 April 1944) was an Italian politician, scholar and financier, who was among the founders of many significant state-run finance institutions in Italy.

Early life and education

Beneduce was born in Caserta ...

at the head of this institute.

In 1912, Giolitti had the Parliament approve an electoral reform bill that expanded the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters – introducing near universal male suffrage – while commenting that first "teaching everyone to read and write" would have been a more reasonable route.[De Grand, ]

The Hunchback's Tailor

', p. 138 Considered his most daring political move, the reform probably hastened the end of the Giolittian Era because his followers controlled fewer seats after the 1913.[

During his ministry, the Parliament approved a law requiring the payment of a monthly allowance to deputies. In fact, at that time the parliamentarians had no type of salary, and this favored the wealthy candidates.

]

Libyan War

The claims of Italy over Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

dated back to Turkey's defeat by Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

in the war of 1877–1878 and subsequent discussions after the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

in 1878, in which France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

had agreed to the occupation of Tunisia and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

respectively, both parts of the then declining Ottoman Empire. When Italian diplomats hinted about possible opposition by their government, the French replied that Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

would have been a counterpart for Italy. In 1902, Italy and France had signed a secret treaty

A secret treaty is a treaty ( international agreement) in which the contracting state parties have agreed to conceal the treaty's existence or substance from other states and the public.Helmut Tichy and Philip Bittner, "Article 80" in Olivier D ...

which accorded freedom of intervention in Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

; however, the Italian government did little to realize the opportunity and knowledge of Libyan territory and resources remained scarce in the following years.

The Italian press began a large-scale lobbying campaign in favour of an invasion of Libya at the end of March 1911. It was fancifully depicted as rich in minerals, well-watered, and defended by only 4,000 Ottoman troops. Also, the population was described as hostile to the

The Italian press began a large-scale lobbying campaign in favour of an invasion of Libya at the end of March 1911. It was fancifully depicted as rich in minerals, well-watered, and defended by only 4,000 Ottoman troops. Also, the population was described as hostile to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and friendly to the Italians: the future invasion was going to be little more than a "military walk", according to them.

The Italian government was hesitant initially, but in the summer the preparations for the invasion were carried out and Prime Minister Giolitti began to probe the other European major powers about their reactions to a possible invasion of Libya. The Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

party had strong influence over public opinion; however, it was in opposition and also divided on the issue, acting ineffectively against a military intervention.

An ultimatum was presented to the Ottoman government led by the Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP) party on the night of 26–27 September. Through Austian intermediation, the Ottomans replied with the proposal of transferring control of Libya without war, maintaining a formal Ottoman suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

. This suggestion was comparable to the situation in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, which was under formal Ottoman suzerainty, but was actually controlled by the United Kingdom. Giolitti refused, and war was declared on September 29, 1911.

On 18 October 1912 Turkey officially surrendered. As a result of this conflict, Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

(province), of which the main sub-provinces were Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

, Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, and Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

itself. These territories together formed what became known as Italian Libya

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

.

During the conflict, Italian forces also occupied the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

. Italy had agreed to return the Dodecanese to the Ottoman Empire according to the Treaty of Ouchy in 1912 (also known as the First Treaty of Lausanne (1912), as it was signed at the Château d'Ouchy

The Château d'Ouchy (Castle of Ouchy) is a hotel built on the site of an old medieval castle in Lausanne, Switzerland by :fr:Jean-Jacques Mercier between 1889 and 1893.

It belongs to hotel division of the Sandoz Family Foundation.

History ...

in Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR-74), ...

, Switzerland.) However, the vagueness of the text allowed a provisional Italian administration of the islands, and Turkey eventually renounced all claims on these islands in Article 15 of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.[Full text of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)](_blank)

/ref>

Although minor, the war was a precursor of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

as it sparked nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

in the Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

states. Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the weakened Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

attacked the Ottoman Empire before the war with Italy had ended.

The invasion of Libya was a costly enterprise for Italy. Instead of the 30 million lire a month judged sufficient at its beginning, it reached a cost of 80 million a month for a much longer period than was originally estimated. The war cost Italy 1.3 billion lire, nearly a billion more than Giolitti estimated before the war.[Mark I. Choate]

''Emigrant nation: the making of Italy abroad''

Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retirem ...

, 2008, , page 175.

Foundation of the Liberal Union

In 1913, Giolitti founded the Liberal Union, which was simply and collectively called Liberals. The Union was a political alliance formed when the Left and the Right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of Liberty, freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convent ...

merged in a single centrist and liberal coalition which largely dominated the Italian Parliament

The Italian Parliament ( it, Parlamento italiano) is the national parliament of the Italian Republic. It is the representative body of Italian citizens and is the successor to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1943), the transitio ...

.

Giolitti had mastered the political concept of ''trasformismo

''Trasformismo'' is the method of making a flexible centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the political left and the political right in Italian politics after the Italian unification and before the rise of Benito Mussoli ...

'', which consisted in making flexible centrist

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to Left-w ...

coalitions of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

which isolated the extremes of the political left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

and the political right

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, auth ...

.

Gentiloni Pact

In 1904,

In 1904, Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of C ...

informally gave permission to Catholics to vote for government candidates in areas where the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

might win. Since the Socialists were the arch-enemy of the Church, the reductionist logic of the Church led it to promote any anti-Socialist measures. Voting for the Socialists was grounds for excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

from the Church.

When the Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of C ...

lifted the ban on Catholic participation in politics in 1913, and the electorate was expanded, he collaborated with the Catholic Electoral Union, led by Ottorino Gentiloni

Count Vincenzo Ottorino Gentiloni (13 October 1865 – 2 August 1916) was an Italian politician, one of the early leaders of the Italian Catholic Azione Cattolica movement. He was born near Ancona, was active in Catholic politics from the 1890s, an ...

in the Gentiloni pact. It directed Catholic voters to Giolitti supporters who agreed to favour the Church's position on such key issues as funding private Catholic schools, and blocking a law allowing divorce.

The Vatican had two major goals at this point: to stem the rise of Socialism and to monitor the grassroots Catholic organizations (co-ops, peasant leagues, credit unions, etc.). Since the masses tended to be deeply religious but rather uneducated, the Church felt they were in need of conveyance so that they did not support improper ideals like Socialism or Anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

. Meanwhile, Italian Prime Minister Giolitti understood that the time was ripe for cooperation between Catholics and the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

system of government.

1913 election and resignation

A general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

was held on 26 October 1913, with a second round of voting on 2 November.Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

, while the Radical Party emerged as the largest opposition bloc. Both groupings did particularly well in Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

, while the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

gained eight seats and was the largest party in Emilia-Romagna

egl, Emigliàn (man) egl, Emiglièna (woman) rgn, Rumagnòl (man) rgn, Rumagnòla (woman) it, Emiliano (man) it, Emiliana (woman) or it, Romagnolo (man) it, Romagnola (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title ...

;[Piergiorgio Corbetta; Maria Serena Piretti, ''Atlante storico-elettorale d'Italia'', Zanichelli, ]Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nat ...

2009. however, the election marked the beginning of the decline of Liberal establishment.

In March 1914, the Radicals of Ettore Sacchi

Ettore Sacchi (31 May 1851 – 6 April 1924) was an Italian lawyer and politician. He was one of the founders and main leaders of the Italian Radical Party.

Biography

Ettore Sacchi was born in Cremona in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia on 31 ...

brought down Giolitti's coalition, who resigned on March 21.

World War I

After Gioilitti's resignation, the conservative

After Gioilitti's resignation, the conservative Antonio Salandra

Antonio Salandra (13 August 1853 – 9 December 1931) was a conservative Italian politician who served as the 21st prime minister of Italy between 1914 and 1916. He ensured the entry of Italy in World War I on the side of the Triple Entente (the ...

was brought into the national cabinet as the choice of Giolitti himself, who still commanded the support of most Italian parliamentarians; however, Salandra soon fell out with Giolitti over the question of Italian participation in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Giolitti opposed Italy's entry into the war on the grounds that Italy was militarily unprepared. At the outbreak of the war in August 1914, Salandra declared that Italy would not commit its troops, maintaining that the Triple Alliance had only a defensive stance and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

had been the aggressor. In reality, both Salandra and his ministers of Foreign Affairs, Antonino Paternò Castello Antonino may refer to:

* Antonino (name), a given name and a surname (including a list of people with the name)

* Antonino, Kansas, an unincorporated community in Ellis County, Kansas, United States

See also

* Antoniano (disambiguation)

* Anto� ...

, who was succeeded by Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il Gio ...

in November 1914, began to probe which side would grant the best reward for Italy's entrance in the war and to fulfil Italy's irredentist claims.[Baker, Ray Stannard (1923). ''Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, Volume I'', Doubleday, Page and Company]

pp. 52–55

/ref>

On 26 April 1915, a secret pact, the Treaty of London or London Pact ( it, Patto di Londra), was signed between the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

(the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

) and the Kingdom of Italy. According to the pact, Italy was to leave the Triple Alliance and join the Triple Entente. Italy was to declare war against Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

within a month in return for territorial concessions at the end of the war.[ Giolitti was initially unaware of the treaty. His aim was to get concessions from Austria-Hungary to avoid war.][Clark, ''Modern Italy: 1871 to the present'']

p. 221-22

/ref>

While Giolitti supported neutrality, Salandra and Sonnino, supported intervention on the side of the Allies, and secured Italy's entrance into the war despite the opposition of the majority in parliament (''see Radiosomaggismo''). On 3 May 1915, Italy officially revoked the Triple Alliance. In the following days Giolitti and the neutralist majority of the Parliament opposed declaring war, while nationalist crowds demonstrated in public areas for entering the war. On 13 May 1915, Salandra offered his resignation, but Giolitti, fearful of nationalist disorder that might break into open rebellion, declined to succeed him as prime minister and Salandra's resignation was not accepted. On 23 May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.

On 18 May 1915, Giovanni Giolitti retired to Cavour and kept aloof from politics for the duration of the conflict.

Fifth term as Prime Minister

Giolitti returned to politics after the end of the conflict. In the electoral campaign of 1919 he charged that an aggressive minority had dragged Italy into war against the will of the majority, putting him at odds with the growing movement of Fascists

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

.[ This election was the first one to be held with a ]proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

system, which was introduced by the government of Francesco Saverio Nitti

Francesco Saverio Vincenzo de Paolo Nitti (19 July 1868 – 20 February 1953) was an Italian economist and political figure. A Radical, he served as Prime Minister of Italy between 1919 and 1920.

According to the ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (" ...

.

Red Biennium

The election took place in the middle of ''

The election took place in the middle of ''Biennio Rosso

The Biennio Rosso (English: "Red Biennium" or "Two Red Years") was a two-year period, between 1919 and 1920, of intense social conflict in Italy, following the First World War.Brunella Dalla Casa, ''Composizione di classe, rivendicazioni e prof ...

'' ("Red Biennium") a two-year period, between 1919 and 1920, of intense social conflict in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, following the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.[Brunella Dalla Casa, ''Composizione di classe, rivendicazioni e professionalità nelle lotte del "biennio rosso" a Bologna'', in: AA. VV, ''Bologna 1920; le origini del fascismo'', a cura di Luciano Casali, Cappelli, Bologna 1982, p. 179.] The revolutionary period was followed by the violent reaction of the Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Nation ...

militia and eventually by the March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, ...

of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

in 1922.

The ''Biennio Ross''o took place in a context of economic crisis at the end of the war, with high unemployment and political instability. It was characterized by mass strikes, worker manifestations as well as self-management experiments through land and factories occupations.Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, workers councils

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

were formed and many factory occupations

Occupation of factories is a method of the workers' movement used to prevent lock outs. They may sometimes lead to "recovered factories", in which the workers self-manage the factories.

They have been used in many strike actions, including:

*t ...

took place under the leadership of anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

s. The agitations also extended to the agricultural areas of the Padan plain

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

and were accompanied by peasant strikes, rural unrests and guerrilla conflicts between left-wing and right-wing militias.

In the general election, the fragmented Liberal governing coalition lost the absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

, due to the success of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

and the Italian People's Party.

Fiume Exploit

Before entering the war, Italy had made a pact with the Allies, the Treaty of London, in which it was promised all of the Austrian Littoral, but not the city of Fiume