Germanic Umlaut on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

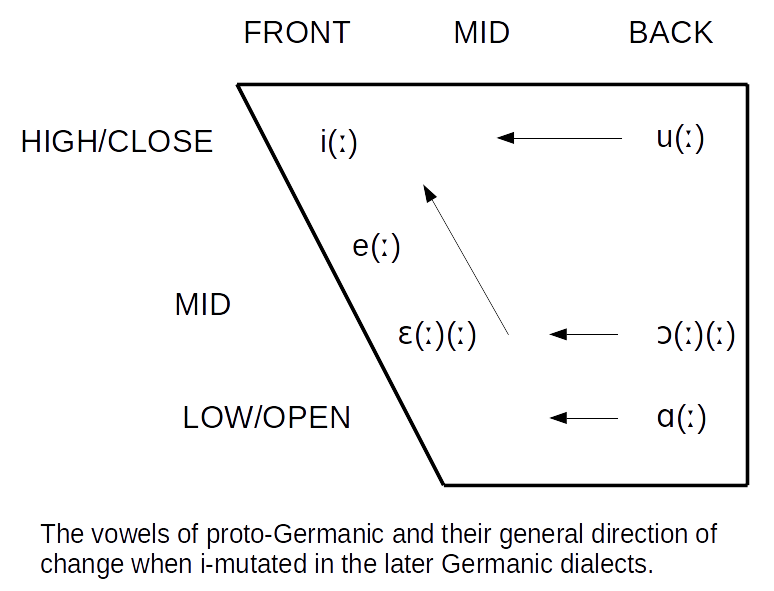

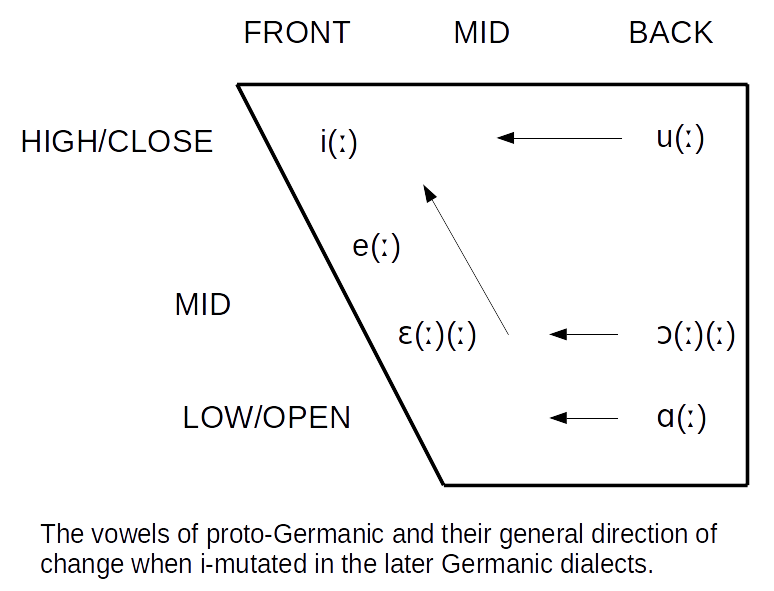

The Germanic umlaut (sometimes called i-umlaut or i-mutation) is a type of linguistic umlaut in which a

Germanic umlaut is a specific historical example of this process that took place in the unattested earliest stages of

Germanic umlaut is a specific historical example of this process that took place in the unattested earliest stages of

German orthography is generally consistent in its representation of i-umlaut. The umlaut diacritic, consisting of two dots above the vowel, is used for the fronted vowels, making the historical process much more visible in the modern language than is the case in English: – , – , – , – . This is a neat solution when pairs of words with and without umlaut mutation are compared, as in umlauted plurals like – ("mother" – "mothers").

However, in a small number of words, a vowel affected by i-umlaut is not marked with the umlaut diacritic because its origin is not obvious. Either there is no unumlauted equivalent or they are not recognized as a pair because the meanings have drifted apart. The adjective ("ready, finished"; originally "ready to go") contains an umlaut mutation, but it is spelled with rather than as its relationship to ("journey") has, for most speakers of the language, been lost from sight. Likewise, ("old") has the comparative ("older"), but the noun from this is spelled ("parents"). ("effort") has the verb ("to spend, to dedicate") and the adjective ("requiring effort") though the 1996 spelling reform now permits the alternative spelling (but not ). For , see

German orthography is generally consistent in its representation of i-umlaut. The umlaut diacritic, consisting of two dots above the vowel, is used for the fronted vowels, making the historical process much more visible in the modern language than is the case in English: – , – , – , – . This is a neat solution when pairs of words with and without umlaut mutation are compared, as in umlauted plurals like – ("mother" – "mothers").

However, in a small number of words, a vowel affected by i-umlaut is not marked with the umlaut diacritic because its origin is not obvious. Either there is no unumlauted equivalent or they are not recognized as a pair because the meanings have drifted apart. The adjective ("ready, finished"; originally "ready to go") contains an umlaut mutation, but it is spelled with rather than as its relationship to ("journey") has, for most speakers of the language, been lost from sight. Likewise, ("old") has the comparative ("older"), but the noun from this is spelled ("parents"). ("effort") has the verb ("to spend, to dedicate") and the adjective ("requiring effort") though the 1996 spelling reform now permits the alternative spelling (but not ). For , see

The German phonological umlaut is present in the

The German phonological umlaut is present in the

I-mutation generally affected Old English vowels as follows in each of the main dialects. It led to the introduction into Old English of the new sounds , (which, in most varieties, soon turned into ), and a sound written in Early West Saxon manuscripts as but whose phonetic value is debated.

I-mutation is particularly visible in the inflectional and derivational morphology of Old English since it affected so many of the Old English vowels. Of 16 basic vowels and diphthongs in

I-mutation generally affected Old English vowels as follows in each of the main dialects. It led to the introduction into Old English of the new sounds , (which, in most varieties, soon turned into ), and a sound written in Early West Saxon manuscripts as but whose phonetic value is debated.

I-mutation is particularly visible in the inflectional and derivational morphology of Old English since it affected so many of the Old English vowels. Of 16 basic vowels and diphthongs in

* Cercignani, Fausto, ''On the Germanic and Old High German distance assimilation changes'', in «Linguistik online», 116/4, 2022, pp. 41–59

{{DEFAULTSORT:Germanic Umlaut Assimilation (linguistics) Vowel shifts German language Linguistic morphology Germanic language histories Indo-European linguistics Germanic languages Germanic philology Sound laws

back vowel

A back vowel is any in a class of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the highest point of the tongue is positioned relatively back in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be c ...

changes to the associated front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

( fronting) or a front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

becomes closer to ( raising) when the following syllable contains , , or .

It took place separately in various Germanic languages starting around AD 450 or 500 and affected all of the early languages except Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

. An example of the resulting vowel alternation is the English plural ''foot ~ feet'' (from Proto-Germanic , pl. ). Germanic umlaut, as covered in this article, does not include other historical vowel phenomena that operated in the history of the Germanic languages such as Germanic a-mutation and the various language-specific processes of u-mutation, nor the earlier Indo-European ablaut

In linguistics, the Indo-European ablaut (, from German '' Ablaut'' ) is a system of apophony (regular vowel variations) in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

An example of ablaut in English is the strong verb ''sing, sang, sung'' and its ...

(''vowel gradation''), which is observable in the conjugation of Germanic strong verb

In the Germanic languages, a strong verb is a verb that marks its past tense by means of changes to the stem vowel ( ablaut). The majority of the remaining verbs form the past tense by means of a dental suffix (e.g. ''-ed'' in English), and are k ...

s such as ''sing/sang/sung''.

While Germanic umlaut has had important consequences for all modern Germanic languages, its effects are particularly apparent in German, because vowels resulting from umlaut are generally spelled with a specific set of letters: , , and , usually pronounced / ɛ/ (formerly / æ/), / ø/, and / y/. Umlaut is a form of assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

* Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

** Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the prog ...

or vowel harmony

In phonology, vowel harmony is an assimilatory process in which the vowels of a given domain – typically a phonological word – have to be members of the same natural class (thus "in harmony"). Vowel harmony is typically long distance, me ...

, the process by which one speech sound is altered to make it more like another adjacent sound. If a word has two vowels with one far back in the mouth and the other far forward, more effort is required to pronounce the word than if the vowels were closer together; therefore, one possible linguistic development is for these two vowels to be drawn closer together.

Description

Germanic umlaut is a specific historical example of this process that took place in the unattested earliest stages of

Germanic umlaut is a specific historical example of this process that took place in the unattested earliest stages of Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

and Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

and apparently later in Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

, and some other old Germanic languages. The precise developments varied from one language to another, but the general trend was this:

* Whenever a back vowel

A back vowel is any in a class of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the highest point of the tongue is positioned relatively back in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be c ...

(, or , whether long or short) occurred in a syllable and the front vowel or the front glide occurred in the next, the vowel in the first syllable was fronted (usually to , , and respectively). Thus, for example, West Germanic "mice" shifted to proto-Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

, which eventually developed to modern ''mice'', while the singular form lacked a following and was unaffected, eventually becoming modern ''mouse''.

* When a low or mid-front vowel occurred in a syllable and the front vowel or the front glide occurred in the next, the vowel in the first syllable was raised. This happened less often in the Germanic languages, partly because of earlier vowel harmony in similar contexts. However, for example, proto-Old English became in, for example, > 'bed'.

The fronted variant caused by umlaut was originally allophonic

In phonology, an allophone (; from the Greek , , 'other' and , , 'voice, sound') is a set of multiple possible spoken soundsor ''phones''or signs used to pronounce a single phoneme in a particular language. For example, in English, (as in ' ...

(a variant sound automatically predictable from the context), but it later became phonemic (a separate sound in its own right) when the context was lost but the variant sound remained. The following examples show how, when final was lost, the variant sound became a new phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

in Old English:

Outcomes in modern spelling and pronunciation

The following table surveys howProto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from pre-Proto-Germanic into three Germanic br ...

vowels which later underwent i-umlaut generally appear in modern languages — though there are many exceptions to these patterns owing to other sound-changes and chance variations. The table gives two West Germanic examples (English and German) and two North Germanic examples (Swedish, from the east, and Icelandic, from the west). Spellings are marked by pointy brackets (⟨...⟩) and pronunciation, given in the international phonetic alphabet

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin script. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association in the late 19th century as a standardized representation ...

, in slashes (/.../).

Whereas modern English does not have any special letters for vowels produced by i-umlaut, in German the letters , , and almost always represent umlauted vowels (see further below). Likewise, in Swedish , , and and Icelandic , , , and are almost always used of vowels produced by i-umlaut. However, German represents vowels from multiple sources, which is also the case for in Swedish and Icelandic.

German orthography

German orthography is generally consistent in its representation of i-umlaut. The umlaut diacritic, consisting of two dots above the vowel, is used for the fronted vowels, making the historical process much more visible in the modern language than is the case in English: – , – , – , – . This is a neat solution when pairs of words with and without umlaut mutation are compared, as in umlauted plurals like – ("mother" – "mothers").

However, in a small number of words, a vowel affected by i-umlaut is not marked with the umlaut diacritic because its origin is not obvious. Either there is no unumlauted equivalent or they are not recognized as a pair because the meanings have drifted apart. The adjective ("ready, finished"; originally "ready to go") contains an umlaut mutation, but it is spelled with rather than as its relationship to ("journey") has, for most speakers of the language, been lost from sight. Likewise, ("old") has the comparative ("older"), but the noun from this is spelled ("parents"). ("effort") has the verb ("to spend, to dedicate") and the adjective ("requiring effort") though the 1996 spelling reform now permits the alternative spelling (but not ). For , see

German orthography is generally consistent in its representation of i-umlaut. The umlaut diacritic, consisting of two dots above the vowel, is used for the fronted vowels, making the historical process much more visible in the modern language than is the case in English: – , – , – , – . This is a neat solution when pairs of words with and without umlaut mutation are compared, as in umlauted plurals like – ("mother" – "mothers").

However, in a small number of words, a vowel affected by i-umlaut is not marked with the umlaut diacritic because its origin is not obvious. Either there is no unumlauted equivalent or they are not recognized as a pair because the meanings have drifted apart. The adjective ("ready, finished"; originally "ready to go") contains an umlaut mutation, but it is spelled with rather than as its relationship to ("journey") has, for most speakers of the language, been lost from sight. Likewise, ("old") has the comparative ("older"), but the noun from this is spelled ("parents"). ("effort") has the verb ("to spend, to dedicate") and the adjective ("requiring effort") though the 1996 spelling reform now permits the alternative spelling (but not ). For , see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

* Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

*Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

*Fred Below ...

.

Some words have umlaut diacritics that do not mark a vowel produced by the sound change of umlaut. This includes loanwords such as from English ''kangaroo'', and from French . Here the diacritic is a purely phonological marker, indicating that the English and French sounds (or at least, the approximation of them used in German) are identical to the native German umlauted sounds. Similarly, Big Mac

The Big Mac is a hamburger sold by the international fast food restaurant chain McDonald's. It was introduced in the Greater Pittsburgh area in 1967 and across the United States in 1968. It is one of the company's flagship products and sign ...

was originally spelt in German. In borrowings from Latin and Greek, Latin , , or Greek , , are rendered in German as and respectively (, "Egypt", or , "economy"). However, Latin/Greek is written in German instead of (). There are also several non-borrowed words where the vowels ''ö'' and ''ü'' have not arisen through historical umlaut, but due to rounding

Rounding means replacing a number with an approximate value that has a shorter, simpler, or more explicit representation. For example, replacing $ with $, the fraction 312/937 with 1/3, or the expression with .

Rounding is often done to ob ...

of an earlier unrounded front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

(possibly from the labial

The term ''labial'' originates from '' Labium'' (Latin for "lip"), and is the adjective that describes anything of or related to lips, such as lip-like structures. Thus, it may refer to:

* the lips

** In linguistics, a labial consonant

** In zoolog ...

/ labialized consonants occurring on both sides), such as ("five"; from Middle High German ), and ("twelve"; from ), and ("create"; from ).

Substitution

When German words (names in particular) are written in the basic Latin alphabet, umlauts are usually substituted with , and to differentiate them from simple , , and .Orthography and design history

The German phonological umlaut is present in the

The German phonological umlaut is present in the Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

period and continues to develop in Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. Hig ...

. From the Middle High German, it was sometimes denoted in written German by adding an to the affected vowel, either after the vowel or, in the small form, above it. This can still be seen in some names: Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

, Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, Staedtler

Staedtler Mars GmbH & Co. KG () is a German multinational stationery manufacturing company based in Nuremberg. The firm was founded by J.S. Staedtler (1800–1872) in 1835 and produces a large variety of stationery products, such as writing im ...

.

In blackletter

Blackletter (sometimes black letter), also known as Gothic script, Gothic minuscule, or Textura, was a script used throughout Western Europe from approximately 1150 until the 17th century. It continued to be commonly used for the Danish, Norwe ...

handwriting, as used in German manuscripts of the later Middle Ages and also in many printed texts of the early modern period, the superscript still had a form that would now be recognisable as an , but in manuscript writing, umlauted vowels could be indicated by two dots since the late medieval period.

Unusual umlaut designs are sometimes also created for graphic design purposes, such as to fit an umlaut into tightly-spaced lines of text. It may include umlauts placed vertically or inside the body of the letter.

Morphological effects

Although umlaut was not a grammatical process, umlauted vowels often serve to distinguish grammatical forms (and thus show similarities to ablaut when viewed synchronically), as can be seen in the English word ''man''. In ancient Germanic, it and some other words had the plural suffix , with the same vowel as the singular. As it contained an , this suffix caused fronting of the vowel, and when the suffix later disappeared, the mutated vowel remained as the only plural marker: ''men''. In English, such plurals are rare: ''man, woman, tooth, goose, foot, mouse, louse, brother'' (archaic or specialized plural in ''brethren''), and ''cow'' (poetic and dialectal plural in ''kine''). It also can be found in a few fossilizeddiminutive

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A ( abbreviated ) is a word-form ...

forms, such as ''kitten'' from ''cat'' and ''kernel'' from ''corn'', and the feminine ''vixen'' from ''fox''. Umlaut is conspicuous when it occurs in one of such a pair of forms, but there are many mutated words without an unmutated parallel form. Germanic actively derived causative weak verbs from ordinary strong verbs by applying a suffix, which later caused umlaut, to a past tense form. Some of these survived into modern English as doublets of verbs, including ''fell'' and ''set'' vs. ''fall'' and ''sit''. Umlaut could occur in borrowings as well if stressed vowel was coloured by a subsequent front vowel, such as German , "Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

", from Latin , or , "cheese", from Latin .

Parallel umlauts in some modern Germanic languages

Umlaut in Germanic verbs

Some interesting examples of umlaut involve vowel distinctions in Germanic verbs. Although these are often subsumed under the heading "ablaut" in tables of Germanic irregular verbs, they are a separate phenomenon.Present stem Umlaut in strong verbs

A variety of umlaut occurs in the second and third person singular forms of the present tense of someGermanic strong verb

In the Germanic languages, a strong verb is a verb that marks its past tense by means of changes to the stem vowel ( ablaut). The majority of the remaining verbs form the past tense by means of a dental suffix (e.g. ''-ed'' in English), and are k ...

s. For example, German ("to catch") has the present tense . The verb ("give") has the present tense , but the shift → would not be a normal result of umlaut in German. There are, in fact, two distinct phenomena at play here; the first is indeed umlaut as it is best known, but the second is older and occurred already in Proto-Germanic itself. In both cases, a following triggered a vowel change, but in Proto-Germanic, it affected only . The effect on back vowels did not occur until hundreds of years later, after the Germanic languages had already begun to split up: , with no umlaut of , but , with umlaut of .

Present stem Umlaut in weak verbs ()

The German word ("reverse umlaut"), sometimes known in English as "unmutation", is a term given to the vowel distinction between present and preterite forms of certainGermanic weak verb

In the Germanic languages, weak verbs are by far the largest group of verbs, are therefore often regarded as the norm (the regular verbs). They are distinguished from the Germanic strong verbs by the fact that their past tense form is marked b ...

s. These verbs exhibit the dental suffix used to form the preterite of weak verbs, and also exhibit what appears to be the vowel gradation characteristic of strong verbs. Examples in English are think/thought, bring/brought, tell/told, sell/sold. The phenomenon can also be observed in some German verbs including ("burn/burnt"), ("know/knew"), and a handful of others. In some dialects, particularly of western Germany, the phenomenon is preserved in many more forms (for example Luxembourgish

Luxembourgish ( ; also ''Luxemburgish'', ''Luxembourgian'', ''Letzebu(e)rgesch''; Luxembourgish: ) is a West Germanic language that is spoken mainly in Luxembourg. About 400,000 people speak Luxembourgish worldwide.

As a standard form of th ...

, "to put", and Limburgish

Limburgish ( li, Limburgs or ; nl, Limburgs ; german: Limburgisch ; french: Limbourgeois ), also called Limburgan, Limburgian, or Limburgic, is a West Germanic language spoken in the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg and in the neig ...

, "to tell, count"). The cause lies with the insertion of the semivowel between the verb stem and inflectional ending. This triggers umlaut, as explained above. In short stem verbs, the is present in both the present and preterite. In long stem verbs however, the fell out of the preterite. Thus, while short stem verbs exhibit umlaut in all tenses, long stem verbs only do so in the present. When the German philologist Jacob Grimm first attempted to explain the phenomenon, he assumed that the lack of umlaut in the preterite resulted from the reversal of umlaut. In actuality, umlaut never occurred in the first place. Nevertheless, the term "Rückumlaut" makes some sense since the verb exhibits a shift from an umlauted vowel in the basic form (the infinitive) to a plain vowel in the respective inflections.

Umlaut as a subjunctive marker

In German, some verbs which display a back vowel in the past tense undergo umlaut in thesubjunctive mood

The subjunctive (also known as conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of the utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude towards it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality ...

: (ind.) → (subj.) ("sing/sang"); (ind.) → (subj.) ("fence/fenced"). Again, this is due to the presence of a following in the verb endings in the Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

period.

Historical survey by language

West Germanic languages

Although umlaut operated the same way in all the West Germanic languages, the exact words in which it took place and the outcomes of the process differ between the languages. Of particular note is the loss of word-final after heavy syllables. In the more southern languages (Old High German, Old Dutch, Old Saxon), forms that lost often show no umlaut, but in the more northern languages (Old English, Old Frisian), the forms do. Compare Old English "guest", which shows umlaut, and Old High German , which does not, both from Proto-Germanic . That may mean that there was dialectal variation in the timing and spread of the two changes, with final loss happening before umlaut in the south but after it in the north. On the other hand, umlaut may have still been partly allophonic, and the loss of the conditioning sound may have triggered an "un-umlauting" of the preceding vowel. Nevertheless, medial consistently triggers umlaut although its subsequent loss is universal in West Germanic except for Old Saxon and early Old High German.I-mutation in Old English

I-mutation generally affected Old English vowels as follows in each of the main dialects. It led to the introduction into Old English of the new sounds , (which, in most varieties, soon turned into ), and a sound written in Early West Saxon manuscripts as but whose phonetic value is debated.

I-mutation is particularly visible in the inflectional and derivational morphology of Old English since it affected so many of the Old English vowels. Of 16 basic vowels and diphthongs in

I-mutation generally affected Old English vowels as follows in each of the main dialects. It led to the introduction into Old English of the new sounds , (which, in most varieties, soon turned into ), and a sound written in Early West Saxon manuscripts as but whose phonetic value is debated.

I-mutation is particularly visible in the inflectional and derivational morphology of Old English since it affected so many of the Old English vowels. Of 16 basic vowels and diphthongs in Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

, only the four vowels were unaffected by i-mutation. Although i-mutation was originally triggered by an or in the syllable following the affected vowel, by the time of the surviving Old English texts, the or had generally changed (usually to ) or been lost entirely, with the result that i-mutation generally appears as a morphological process that affects a certain (seemingly arbitrary) set of forms. These are most common forms affected:

*The plural, and genitive/dative singular, forms of consonant-declension nouns (Proto-Germanic (PGmc) ), as compared to the nominative/accusative singular – e.g., "foot", "feet"; "mouse", "mice". Many more words were affected by this change in Old English vs. modern English – e.g., "book", "books"; "friend", "friends".

*The second and third person present

The present (or here'' and ''now) is the time that is associated with the events perceived directly and in the first time, not as a recollection (perceived more than once) or a speculation (predicted, hypothesis, uncertain). It is a period of ...

singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular homology

* SINGULAR, an open source Computer Algebra System (CAS)

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar ...

indicative of strong verbs (Pre-Old-English (Pre-OE) , ), as compared to the infinitive

Infinitive ( abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all languages. The word is de ...

and other present-tense forms – e.g. "to help", "(I) help", "(you sg.) help", "(he/she) helps", "(we/you pl./they) help".

*The comparative form of some adjective

In linguistics, an adjective ( abbreviated ) is a word that generally modifies a noun or noun phrase or describes its referent. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives were considered one of the ...

s (Pre-OE < PGmc , Pre-OE < PGmc ), as compared to the base form – e.g. "old", "older", "oldest" (cf. "elder, eldest").

*Throughout the first class of weak verbs (original suffix ), as compared to the forms from which the verbs were derived – e.g. "food", "to feed" < Pre-OE ; "lore", "to teach"; "to fall", "to fell".

*In the abstract nouns in (PGmc ) corresponding to certain adjectives – e.g., "strong", "strength"; "whole/hale", "health"; "foul", "filth".

*In female forms of several nouns with the suffix (PGmc ) – e.g., "god", "goddess" (cf. German , ); "fox", "vixen".

*In i-stem abstract nouns derived from verbs (PGmc ) – e.g. "a coming", "to come"; "a son (orig., a being born)", "to bear"; "a falling", "to fall"; "a bond", "to bind". Note that in some cases the abstract noun has a different vowel than the corresponding verb, due to Proto-Indo-European ablaut.

=Notes

= #The phonologically expected umlaut of is . However, in many cases appears. Most in Old English stem from earlier because of a change calleda-restoration

The phonology, phonological system of the Old English language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included a number of vowel shifts, and the palatalization (sound change), palatalisation of velar consonants in ma ...

. This change was blocked when or followed, leaving , which subsequently mutated to . For example, in the case of "tale" vs. "to tell", the forms at one point in the early history of Old English were and , respectively. A-restoration converted to , but left alone, and it subsequently evolved to by i-mutation. The same process "should" have led to instead of . That is, the early forms were and . A-restoration converted to but left alone , which would normally have evolved by umlaut to . In this case, however, once a-restoration took effect, was modified to by analogy with , and then later umlauted to .

#A similar process resulted in the umlaut of sometimes appearing as and sometimes (usually, in fact) as . In Old English, generally stems from a-mutation of original . A-mutation of was blocked by a following or , which later triggered umlaut of the to , the reason for alternations between and being common. Umlaut of to occurs only when an original was modified to by analogy before umlaut took place. For example, comes from late Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from pre-Proto-Germanic into three Germanic br ...

, from earlier . The plural in Proto-Germanic was , with unaffected by a-mutation due to the following . At some point prior to i-mutation, the form was modified to by analogy with the singular form, which then allowed it to be umlauted to a form that resulted in .

A few hundred years after i-umlaut began, another similar change called double umlaut occurred. It was triggered by an or in the third or fourth syllable of a word and mutated ''all'' previous vowels but worked only when the vowel directly preceding the or was . This typically appears as in Old English or is deleted:

* "witch" < PGmc (cf. Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

)

* "embers" < Pre-OE < PGmc (cf. Old High German )

* "errand" < PGmc (cf. Old Saxon

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Europe). I ...

)

* "to hasten" < archaic < Pre-OE

* "upmost" < PGmc (cf. Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

)

As shown by the examples, affected words typically had in the second syllable and in the first syllable. The developed too late to break to or to trigger palatalization of a preceding velar.

I-mutation in High German

I-mutation is visible inOld High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

(OHG), c. 800 AD, only on short , which was mutated to (the so-called "primary umlaut"), although in certain phonological environments the mutation fails to occur. By then, it had already become partly phonologized, since some of the conditioning and sounds had been deleted or modified. The later history of German, however, shows that and , as well as long vowels and diphthongs, and the remaining instances of that had not been umlauted already, were also affected (the so-called "secondary umlaut"); starting in Middle High German, the remaining conditioning environments disappear and and appear as and in the appropriate environments.

That has led to a controversy over when and how i-mutation appeared on these vowels. Some (for example, Herbert Penzl) have suggested that the vowels must have been modified without being indicated for lack of proper symbols and/or because the difference was still partly allophonic. Others (such as Joseph Voyles) have suggested that the i-mutation of and was entirely analogical and pointed to the lack of i-mutation of these vowels in certain places where it would be expected, in contrast to the consistent mutation of . Perhaps the answer is somewhere in between — i-mutation of and was indeed phonetic, occurring late in OHG, but later spread analogically to the environments where the conditioning had already disappeared by OHG (this is where failure of i-mutation is most likely). It must also be kept in mind that it is an issue of relative chronology: already early in the history of attested OHG, some umlauting factors are known to have disappeared (such as word-internal after geminates and clusters), and depending on the age of OHG umlaut, that could explain some cases where expected umlaut is missing. The whole question should now be reconsidered in the light of Fausto Cercignani

Fausto Cercignani (; born March 21, 1941) is an Italian scholar, essayist and poet.

Biography

Born to Tuscan parents, Fausto Cercignani studied in Milan, where he graduated in foreign languages and literatures with a dissertation dealing with ...

's suggestion that the Old High German umlaut phenomena produced phonemic changes before the factors that triggered them off changed or disappeared, because the umlaut allophones gradually shifted to such a degree that they became distinctive in the phonological system of the language and contrastive at a lexical level.

However, sporadic place-name attestations demonstrate the presence of the secondary umlaut already for the early 9th century, which makes it likely that all types of umlaut were indeed already present in Old High German, even if they were not indicated in the spelling. Presumably, they arose already in the early 8th century. Ottar Grønvik, also in view of spellings of the type , , and in the early attestations, affirms the old epenthesis theory, which views the origin of the umlaut vowels in the insertion of after back vowels, not only in West, but also in North Germanic. Fausto Cercignani

Fausto Cercignani (; born March 21, 1941) is an Italian scholar, essayist and poet.

Biography

Born to Tuscan parents, Fausto Cercignani studied in Milan, where he graduated in foreign languages and literatures with a dissertation dealing with ...

prefers the assimilation theory and presents a history of the OHG umlauted vowels up to the present day.

In modern German, umlaut as a marker of the plural of nouns is a regular feature of the language, and although umlaut itself is no longer a productive force in German, new plurals of this type can be created by analogy. Likewise, umlaut marks the comparative of many adjectives and other kinds of derived forms. Because of the grammatical importance of such pairs, the German umlaut diacritic was developed, making the phenomenon very visible. The result in German is that the vowels written as , , and become , , and , and the diphthong becomes : "man" vs. "men", "foot" vs. "feet", "mouse" vs. "mice".

In various dialects, the umlaut became even more important as a morphological marker of the plural after the apocope of final schwa (); that rounded front vowels have become unrounded in many dialects does not prevent them from serving as markers of the plural given that they remain distinct from their non-umlauted counterparts (just like in English ''foot'' – ''feet'', ''mouse'' – ''mice''). The example "guest" vs. "guests" served as the model for analogical pairs like "day" vs. "days" (vs. standard ) and "arm" vs. "arms" (vs. standard ). Even plural forms like "fish" which had never had a front rounded vowel in the first place were interpreted as such (i.e., as if from Middle High German **) and led to singular forms like that are attested in some dialects.

I-mutation in Old Saxon

InOld Saxon

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Europe). I ...

, umlaut is much less apparent than in Old Norse. The only vowel that is regularly fronted before an or is short : – , – . It must have had a greater effect than the orthography shows since all later dialects have a regular umlaut of both long and short vowels.

I-mutation in Dutch

Late Old Dutch saw a merger of and , causing their umlauted results to merge as well, giving . The lengthening in open syllables in early Middle Dutch then lengthened and lowered this short to long (spelled ) in some words. This is parallel to the lowering of in open syllables to , as in ("ship") – ("ships"). In general, the effects of the Germanic umlaut in plural formation are limited. One of the defining phonological features of Dutch, is the general absence of the I-mutation or secondary umlaut when dealing with long vowels. Unlike English and German, Dutch does not palatalize the long vowels, which are notably absent from the language. Thus, for example, where modern German has and English has ''feel'' (from Proto-Germanic ), standard Dutch retains a back vowel in the stem in . Thus, only two of the original Germanic vowels were affected by umlaut at all in Dutch: , which became , and , which became (spelled ). As a result of this relatively sparse occurrence of umlaut, standard Dutch does not use umlaut as a grammatical marker. An exception is the noun "city" which has the irregular umlauted plural . Later developments in Middle Dutch show that long vowels and diphthongs were not affected by umlaut in the more western dialects, including those in westernBrabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

and Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former Provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

that were most influential for standard Dutch. However in what is traditionally called the ''Cologne Expansion'' (the spread of certain West German features in the south-easternmost Dutch dialects during the High Medieval period) the more eastern and southeastern dialects of Dutch, including easternmost Brabantian and all of Limburgish

Limburgish ( li, Limburgs or ; nl, Limburgs ; german: Limburgisch ; french: Limbourgeois ), also called Limburgan, Limburgian, or Limburgic, is a West Germanic language spoken in the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg and in the neig ...

have umlaut of long vowels (or in case of Limburgish, all rounded back vowels), however.R. Belemans: Belgisch-Limburgs, Lannoo Uitgeverij, 2004, pp. 22-25 Consequently, these dialects also make grammatical use of umlaut to form plurals and diminutives, much as most other modern Germanic languages do. Compare and "little man" from .

North Germanic languages

The situation in Old Norse is complicated as there are two forms of i-mutation. Of these two, only one is phonologized. I-mutation in Old Norse is phonological: * InProto-Norse

Proto-Norse (also called Ancient Nordic, Ancient Scandinavian, Ancient Norse, Primitive Norse, Proto-Nordic, Proto-Scandinavian and Proto-North Germanic) was an Indo-European language spoken in Scandinavia that is thought to have evolved as ...

, if the syllable was heavy and followed by vocalic ( > , but > ) or, regardless of syllable weight, if followed by consonantal ( > ). The rule is not perfect, as some light syllables were still umlauted: > , > .

* In Old Norse, if the following syllable contains a remaining Proto-Norse . For example, the root of the dative singular of ''u''-stems are i-mutated as the desinence contains a Proto-Norse , but the dative singular of ''a''-stems is not, as their desinence stems from Proto-Norse .

I-mutation is ''not'' phonological if the vowel of a long syllable is i-mutated by a syncopated ''i''. I-mutation does not occur in short syllables.

See also

* Germanic a-mutation * I-mutation *Indo-European ablaut

In linguistics, the Indo-European ablaut (, from German '' Ablaut'' ) is a system of apophony (regular vowel variations) in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

An example of ablaut in English is the strong verb ''sing, sang, sung'' and its ...

* Umlaut (disambiguation)

* Umlaut (diacritic)

The umlaut () is the diacritical mark used to indicate in writing (as part of the letters , , and ) the result of the historical sound shift due to which former back vowels are now pronounced as front vowels (for example , , and as , , and ). ...

References

Bibliography

* Malmkjær, Kirsten (Ed.) (2002). ''The linguistics encyclopedia'' (2nd ed.). London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. . * Campbell, Lyle (2004). ''Historical Linguistics: An Introduction'' (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press. * Cercignani, Fausto, ''Early "Umlaut" Phenomena in the Germanic Languages'', in «Language», 56/1, 1980, pp. 126–136. * Cercignani, Fausto, ''Alleged Gothic Umlauts'', in «Indogermanische Forschungen», 85, 1980, pp. 207–213. * Cercignani, Fausto, ''The development of the Old High German umlauted vowels and the reflex of New High German /ɛ:/ in Present Standard German'', in «Linguistik online», 113/1, 2022, pp. 45–57* Cercignani, Fausto, ''On the Germanic and Old High German distance assimilation changes'', in «Linguistik online», 116/4, 2022, pp. 41–59

{{DEFAULTSORT:Germanic Umlaut Assimilation (linguistics) Vowel shifts German language Linguistic morphology Germanic language histories Indo-European linguistics Germanic languages Germanic philology Sound laws