German minority in Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The registered German minority in

The registered German minority in

Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011

'. GUS. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29. 01. 2013. p. 3. At a 2002 census there were 152,900 people declaring German ethnicity. The German language is spoken in certain areas in

According to the 2002 census, most of the Germans in Poland (92.9%) live in

According to the 2002 census, most of the Germans in Poland (92.9%) live in

German migration into areas that form part of present-day Poland began with the medieval

German migration into areas that form part of present-day Poland began with the medieval

After Nazi Germany's invasion of the Second Polish Republic in September 1939, many members of the German minority (around 25%Kampania Wrześniowa 1939.pl

After Nazi Germany's invasion of the Second Polish Republic in September 1939, many members of the German minority (around 25%Kampania Wrześniowa 1939.pl

) joined the

German Poles (german: Deutsche Polen, pl, Polacy pochodzenia niemieckiego) may refer to either

German Poles (german: Deutsche Polen, pl, Polacy pochodzenia niemieckiego) may refer to either

(se

contents

or 1,165,000 were naturalized as Polish citizens by 1950.

The Expulsion of 'German' Communities from Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War

'', Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees, European University Institute, Florense. HEC No. 2004/1. p.28 Therefore, most of them were inhabitants of Polish descent of the pre-war border regions of

Telegraph.co.uk

/ref> Despite that, hundreds or tens of thousands of former German citizens remained in Poland. Some of them created families with other

There is one German international school in Poland, Willy-Brandt-Schule in

There is one German international school in Poland, Willy-Brandt-Schule in

*

* IMDb Database

retrieved 17 April 2020

* Romuald Traugutt, (1826 – 1864 in Warsaw) a "dictator" of the

Dual Citizenship in Opole Silesia in the Context of European Integration

', Tomasz Kamusella, Opole University, in ''Facta Universitatis'', series Philosophy, Sociology and Psychology, Vol 2, No 10, 2003, pp. 699–716 * * *

The registered German minority in

The registered German minority in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

at the 2011 national census consisted of 148,000 people, of whom 64,000 declared both German and Polish ethnicities and 45,000 solely German ethnicity.Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011

'. GUS. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29. 01. 2013. p. 3. At a 2002 census there were 152,900 people declaring German ethnicity. The German language is spoken in certain areas in

Opole Voivodeship

Opole Voivodeship, or Opole Province ( pl, województwo opolskie ), is the smallest and least populated voivodeship (province) of Poland. The province's name derives from that of the region's capital and largest city, Opole. It is part of Upper S ...

, where most of the minority resides, and in Silesian Voivodeship

Silesian Voivodeship, or Silesia Province ( pl, województwo śląskie ) is a voivodeship, or province, in southern Poland, centered on the historic region known as Upper Silesia ('), with Katowice serving as its capital.

Despite the Silesian ...

. German-speakers first came to these regions (present-day Opole and Silesian Voivodeships) during the Late Middle Ages. However, there are no localities in either Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

or Poland as a whole where German could be considered a language of everyday communication. The predominant home or family language of Poland's German minority in Upper Silesia used to be the Silesian German language (mainly ''Oberschlesisch'' dialect, but also ''Mundart des Brieg-Grottkauer Landes'' was used west of Opole), but since 1945 Standard German replaced it as these Silesian German dialects went generally out of use except among the oldest generations which have by now completely died off. The German Minority electoral list currently has one seat in the Sejm of the Republic of Poland

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

(there were four from 1993 to 1997), benefiting from the current provision in Polish election law which exempts national minorities from the 5% national threshold.

In the school year of 2014/15 there were 387 elementary schools in Poland (all in Upper Silesia), with over 37,000 students, in which German was taught as a minority language (that is, at least for three periods of 45 minutes in a week), hence ''de facto'' as a subject. There were no minority schools with German as the language of instruction, though there were three asymmetrically bilingual (Polish-German) schools, where most subjects were taught through the medium of Polish. Most members of the German minority are Roman Catholic, while some are Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

Protestants

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

(the Evangelical-Augsburg Church).

Germans in Poland today

According to the 2002 census, most of the Germans in Poland (92.9%) live in

According to the 2002 census, most of the Germans in Poland (92.9%) live in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

: 104,399 in the Opole Voivodeship

Opole Voivodeship, or Opole Province ( pl, województwo opolskie ), is the smallest and least populated voivodeship (province) of Poland. The province's name derives from that of the region's capital and largest city, Opole. It is part of Upper S ...

, i.e. 71.0% of all Germans in Poland and a share of 9.9% of the local population; 30,531 in the Silesian Voivodeship

Silesian Voivodeship, or Silesia Province ( pl, województwo śląskie ) is a voivodeship, or province, in southern Poland, centered on the historic region known as Upper Silesia ('), with Katowice serving as its capital.

Despite the Silesian ...

, i.e. 20.8% of all Germans in Poland and 0.6% of the local population; plus 1,792 in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship

Lower Silesian Voivodeship, or Lower Silesia Province, in southwestern Poland, is one of the 16 voivodeships (provinces) into which Poland is divided. The voivodeship was created on 1 January 1999 out of the former Wrocław, Legnica, Wałbr ...

, i.e. 1.2% of all Germans in Poland, though only 0.06% of the local population. A second region with a notable German minority is Masuria

Masuria (, german: Masuren, Masurian: ''Mazurÿ'') is a ethnographic and geographic region in northern and northeastern Poland, known for its 2,000 lakes. Masuria occupies much of the Masurian Lake District. Administratively, it is part of the ...

, with 4,311 living in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship

Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship or Warmia-Masuria Province or Warmia-Mazury Province (in pl, Województwo warmińsko-mazurskie, is a voivodeship (province) in northeastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Olsztyn. The voivodeship has an a ...

, corresponding to 2.9% of all Germans in Poland, and 0.3% of the local population.

Towns with particularly high concentrations of German speakers in Opole Voivodeship

Opole Voivodeship, or Opole Province ( pl, województwo opolskie ), is the smallest and least populated voivodeship (province) of Poland. The province's name derives from that of the region's capital and largest city, Opole. It is part of Upper S ...

include: Strzelce Opolskie

Strzelce Opolskie (german: Groß Strehlitz, szl, Wielge Strzelce) is a town in southern Poland with 17,900 inhabitants (2019), situated in the Opole Voivodeship. It is the capital of Strzelce County.

Demographics

Strzelce Opolskie is one of t ...

; Dobrodzien; Prudnik

Prudnik (, szl, Prudnik, Prōmnik, german: Neustadt in Oberschlesien, Neustadt an der Prudnik, la, Prudnicium) is a town in southern Poland, located in the southern part of Opole Voivodeship near the border with the Czech Republic. It is the ...

; Głogówek

Głogówek (pronounced , German: ''Oberglogau'', cs, Horní Hlohov, szl, Gogōwek) is a small historic town in southern Poland. It is situated on the Osobloga River, in Opole Voivodeship of the greater Silesian region. The city lies approxi ...

; and Gogolin

Gogolin is a town in southern Poland, in Opole Voivodeship, in Krapkowice County. It has 6,682 inhabitants (2019). It is the seat of Gmina Gogolin.

Geology and palaeontology

Gogolin gives its name to the Gogolin Formation whose strata were fi ...

.

In the remaining 12 voivodeship

A voivodeship is the area administered by a voivode (Governor) in several countries of central and eastern Europe. Voivodeships have existed since medieval times and the area of extent of voivodeship resembles that of a duchy in western medieval ...

s of Poland, the percentage of Germans in the population does not exceed 0.09%:

Poland is also the third most frequent destination for migrant Germans searching for work, after the United States and Switzerland.

History of Germans in Poland

Ostsiedlung

(, literally "East-settling") is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration-period when ethnic Germans moved into the territories in the eastern part of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire (that Germans had alr ...

(see also Walddeutsche in the Subcarpathian region). Regions which subsequently became part of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire'' ...

- Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

, East Brandenburg

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Call ...

, Pomerania and East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1 ...

- were almost completely German by the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 1500 ...

. In other areas of modern-day Poland there were substantial German populations, most notably in the historical regions of Pomerelia

Pomerelia,, la, Pomerellia, Pomerania, pl, Pomerelia (rarely used) also known as Eastern Pomerania,, csb, Pòrénkòwô Pòmòrskô Vistula Pomerania, prior to World War II also known as Polish Pomerania, is a historical sub-region of Pome ...

, Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

, and Posen or Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city ...

. Lutheran Germans settled numerous " Olęder" villages along the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in t ...

River and its tributaries during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. In the 19th century, Germans became actively involved in developing the clothmaking industry in what is now central Poland. Over 3,000 villages and towns within Russian Poland are recorded as having German residents. Many of these Germans remained east of the Curzon line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to th ...

after World War I ended in 1918, including a significant number in Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

. In the late-19th century, some Germans moved westward during the Ostflucht, while a Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an ...

n Settlement Commission established others in Central Poland.

According to the 1931 census, around 740,000 German speakers lived in Poland (2.3% of the population). Their minority rights were protected by the Little Treaty of Versailles of 1919. The right to appeal to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

however was renounced in 1934, officially due to Germany's withdrawal from the League (September 1933) after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

became German Chancellor in January 1933.

WWII

After Nazi Germany's invasion of the Second Polish Republic in September 1939, many members of the German minority (around 25%Kampania Wrześniowa 1939.pl

After Nazi Germany's invasion of the Second Polish Republic in September 1939, many members of the German minority (around 25%Kampania Wrześniowa 1939.pl) joined the

ethnic German

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

paramilitary organisation ''Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz

The ''Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz'' was an ethnic German self-protection militia, a paramilitary organization consisting of ethnic German ('' Volksdeutsche'') mobilized from among the German minority in Poland. The ''Volksdeutscher Selbstsch ...

''. When the German occupation of Poland

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

** ...

began, the ''Selbstschutz'' took an active part in Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles. Due to their pre-war interactions with the Polish majority, they were able to prepare lists of Polish intellectuals and civil servants whom the Nazis selected for extermination. The organisation actively participated and was responsible for the deaths of about 50,000 Poles.

Following the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, the Soviets annexed a massive portion of the eastern part of Poland (November 1939) in the wake of an August 1939 agreement between the Reich and the USSR. During the German occupation of Poland during World War II (1939-1945), the Nazis forcibly resettled ethnic Germans from other areas of Central Europe (such as the Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

) in the pre-war territory of Poland. At the same time the Nazi authorities expelled, enslaved and killed Poles and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites"" ...

.

After the Nazis' defeat in 1945, Poland did not regain its Soviet-annexed territory; instead, Polish communists, directed by the Soviets, expelled the remaining Germans who had not been evacuated or fled before from the areas of Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

, Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

, Pommerania, East Brandenburg

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Call ...

, and East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1 ...

and made Poles take their place, some of whom were expelled from Soviet-occupied areas that had previously formed part of Poland. About half of East Prussia became the newly created Soviet territory of Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and adminis ...

(officially established in 1946), where Soviet citizens replaced the former German residents. Claims to a border along the Oder-Neisse line were presented at the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

of August 1945 by a delegation of Polish politicians. The Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

's results eventually specified or endorsed the shifting of borders pending a later Peace Treaty. In the following years, the communists and activists inspired by the Myśl zachodnia strived to "de-Germanize" and to "re- Polonize" the huge land, propagandistically termed Recovered Territories

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Z ...

.

Following the downfall of the Polish Communist regime in 1989, the German minorities' political situation in modern-day Poland has improved, and after Poland joined the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

in the 2004 enlargement and was incorporated into the Schengen Area

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and ...

, German citizens are now allowed to buy land and property in the areas where they or their ancestors used to live, and can return there if they wish. However, none of their properties have been returned after being confiscated.

A possible demonstration of the ambiguity of the Polish-German minority position can be seen in the life and career of Waldemar Kraft

Waldemar Kraft (19 February 1898 – 12 July 1977) was a German politician. A member of the SS in Nazi Germany, he served as Managing Director of the Reich Association for Land Management in the Annexed Territories from 1940 to 1945, administeri ...

, a minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

in the West German

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Common ...

during the 1950s. However, most of the German minority had not been as involved in the Nazi system as Kraft was.

There is no clear-cut division in Poland between the Germans and some other minorities, whose heritage is similar in some respects due to centuries of assimilation, Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

and intermarriage, but differs in other respects due to either ancient regional West Slavic roots or Polonisation. Examples of such minorities include the Slovincians (''Lebakaschuben''), the Masurians

The Masurians or Mazurs ( pl, Mazurzy; german: Masuren; Masurian: ''Mazurÿ''), historically also known as Prussian Masurians (Polish: ''Mazurzy pruscy''), is an ethnographic group of Polish people, that originate from the region of Masuria ...

and the Silesians of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

. While in the past these people have been claimed for both Polish and German ethnicity, it really depends on their self-perception which they choose to belong to.

German Poles

German Poles (german: Deutsche Polen, pl, Polacy pochodzenia niemieckiego) may refer to either

German Poles (german: Deutsche Polen, pl, Polacy pochodzenia niemieckiego) may refer to either Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland i ...

of German descent or sometimes to Polish citizens whose ancestors held German citizenship before World War II, regardless of their ethnicity.

After the flight and expulsion of Germans from Poland, the largest of a series of flights and expulsions of Germans in Europe during and after World War II, over 1 million former citizens of Germany were naturalized and granted Polish citizenship. Some of them were forced to stay in Poland, while others wanted to stay because these territories were inhabited by their families for hundreds of years. The lowest estimate by West German Schieder commission

Documents on the Expulsion of the Germans from Eastern-Central Europe is the abridged English translation of a multi-volume publication that was created by a commission of West German historians between 1951 and 1961

to document the population tra ...

of 1953, is that 910,000 former German citizens were granted Polish citizenship by 1950. Higher estimates say that 1,043,550PDFs by chapter(se

contents

or 1,165,000 were naturalized as Polish citizens by 1950.

Post-WWII

However, the vast majority of those people were the so-called "autochthons" who were allowed to stay in post-war Poland after declaring Polish ethnicity in a special verification process.The Expulsion of 'German' Communities from Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War

'', Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees, European University Institute, Florense. HEC No. 2004/1. p.28 Therefore, most of them were inhabitants of Polish descent of the pre-war border regions of

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

and Warmia-Masuria

Masuria (, german: Masuren, Masurian: ''Mazurÿ'') is a ethnographic and geographic region in northern and northeastern Poland, known for its 2,000 lakes. Masuria occupies much of the Masurian Lake District. Administratively, it is part of the ...

. Sometimes they were called ''Wasserpolnisch'' or ''Wasserpolak''. Despite their ethnic background, they were allowed to reclaim their former German citizenship on application and under German Basic Law

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland) is the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The West German Constitution was approved in Bonn on 8 May 1949 and came in ...

were "considered as not having been deprived of their German citizenship if they have established their domicile in Germany after May 8, 1945 and have not expressed a contrary intention." Because of this fact many of them left the People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million ne ...

due to its undemocratic political system and economic problems.

It is estimated that, in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

era, hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens decided to emigrate to West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

and, to a lesser extent, to East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In t ...

.Manfred Görtemaker, ''Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Von der Gründung bis zur Gegenwart'', Munich: C.H.Beck, 1999, p. 169, Michael Levitin, Germany provokes anger over museum to refugees who fled Poland during WWII, Telegraph.co.uk, Feb 26, 2009Telegraph.co.uk

/ref> Despite that, hundreds or tens of thousands of former German citizens remained in Poland. Some of them created families with other

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland i ...

, who, in the vast majority, were settlers from central Poland or were resettled from the former eastern territories of Poland by the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

to the Recovered Territories

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Z ...

(Former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

).

Education

Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

.

Notable Poles of German descent

*

* Władysław Anders

)

, birth_name = Władysław Albert Anders

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Krośniewice-Błonie, Warsaw Governorate, Congress Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = London, England, United Kingdom

, serviceyear ...

, (1892 in Warsaw – 1970 in London) general, leader of the Polish 2nd Corps during World War II and prominent member of the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

in London.

* Grzegorz Braun, (born 1967 in Toruń) journalist, academic lecturer, movie director, screenwriter and far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

politician.

* Izabela Czartoryska

Elżbieta "Izabela" Dorota Czartoryska (''née'' Flemming; 3 March 1746 – 15 July 1835) was a Polish princess, writer, art collector, and prominent figure in the Polish Enlightenment. She was the wife of Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski and a ...

, (1746 in Warsaw – 1835 in Wysocko) noblewoman née Flemming, writer, art collector, and founder of the first Polish museum, the Czartoryski Museum

The Princes Czartoryski Museum ( pl, Muzeum Książąt Czartoryskich ) – often abbreviated to Czartoryski Museum – is a historic museum in Kraków, Poland, and one of the country's oldest museums. The initial collection was formed in 1796 in P ...

in Kraków.

* Jan Henryk Dąbrowski

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (; also known as Johann Heinrich Dąbrowski (Dombrowski) in German and Jean Henri Dombrowski in French; 2 August 1755 – 6 June 1818) was a Polish general and statesman, widely respected after his death for his patri ...

, (1755 in Pierzchów – 1818 in Winna Góra) general and Polish national hero.

* Stanisław Ernest Denhoff, (1673 in Kościerzyna– 1728 in Gdansk) noble, politician and military leader.

* Karol Estreicher (senior), (1827 in Kraków – 1908 in Kraków) father of Polish Bibliography and a founder of the Polish Academy of Learning

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences or Polish Academy of Learning ( pl, Polska Akademia Umiejętności), headquartered in Kraków and founded in 1872, is one of two institutions in contemporary Poland having the nature of an academy of sci ...

.

* Adam Fastnacht, (1913 in Sanok - 1987 in Wrocław) historian and member of Armia Krajowa

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II, resistance movement in Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed i ...

.

* Jan Fethke, (1903 in Opole – 1980 in Berlin) film director, author and famous proponent of Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international commun ...

language.

* Emil August Fieldorf, (1895 in Krakow – 1953 in Warsaw) Polish general during World War I and World War II.

* Franciszek Fiszer Franciszek Fiszer (better known as Franc Fiszer; March 25, 1860 – April 9, 1937) was a Polish bon-vivant, gourmand, erudite and philosopher, a friend of the most notable writers and philosophers of contemporary Warsaw and one of Warsaw's semi-lege ...

, (1860 in Ostrołęka – 1937 in Warsaw) author, bon-vivant and philosopher.

* Mark Forster, (born 1983 in Kaiserslautern), singer, songwriter and TV personality

* Anna German

Anna Wiktoria German-Tucholska (14 February 1936 – 26 August 1982) was a Polish singer, immensely popular in Poland and in the Soviet Union in the 1960s–1970s. She released over a dozen music albums with songs in Polish, as well as severa ...

, (1936 in Urgench – 1982 in Warsaw) popular singer

* Małgorzata Gersdorf, (born 1952 in Warsaw) lawyer, judge, Head of Supreme Court of Poland

The Supreme Court ( pl, Sąd Najwyższy) is the highest court in the Republic of Poland. It is located in the Krasiński Square, Warsaw.

One of the chambers of the Supreme Court, the Disciplinary Chamber, was suspended by a judgment of the C ...

* Wanda Gertz

Major Wanda Gertz (13 April 1896 – 10 November 1958) was a Polish woman of noble birth, who began her military career in the Polish Legion during World War I, dressed as a man, under the pseudonym of "Kazimierz 'Kazik' Żuchowicz". She subse ...

, (1896 in Warsaw – 1958 in London) decorated officer in the Polish Army during World War II

* Roman Giertych

Roman Jacek Giertych (; born 27 February 1971 in Śrem, Poland) is a Polish politician and lawyer; he was Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Education until August 2007. He was a member of the Sejm (the lower house of the Polish parliament) f ...

, (born 1971 in Śrem) lawyer, advocate, former Deputy Prime Minister

* Kamil Glik, (born 1988 in Jastrzębie-Zdrój) professional footballer

A football player or footballer is a sportsperson who plays one of the different types of football. The main types of football are association football, American football, Canadian football, Australian rules football, Gaelic football, rugby le ...

who plays for Serie A club Torino

Turin ( , Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The ...

and the Poland national football team

The Poland national football team ( pl, Reprezentacja Polski w piłce nożnej) has represented Poland in men's international tournaments football competitions since their first match in 1921. The team is controlled by the Polish Football Associ ...

.

* Henryk Grohman, (1862 in Łódź – 1939) industrialist.

* Józef Haller

Józef Haller von Hallenburg (13 August 1873 – 4 June 1960) was a lieutenant general of the Polish Army, a legionary in the Polish Legions, harcmistrz (the highest Scouting instructor rank in Poland), the president of the Polish Scouti ...

, (1873 in Jurczyce – 1960 in London) Polish general, political and social activist

* Marek Jędraszewski, (born 1949 in Poznań) Archbishop of Kraków

The Archbishop of Kraków is the head of the archdiocese of Kraków. A bishop of Kraków first came into existence when the diocese was created in 1000; it was promoted to an archdiocese on 28 October 1925. Due to Kraków's role as Poland's polit ...

since 2016 (his mother was connected with Bambers)

* Miroslav Klose

Miroslav Josef Klose (, pl, Mirosław Józef Klose; born 9 June 1978 as Mirosław Marian Klose) is a German professional football manager and former player who is the head coach of Austrian Bundesliga club Rheindorf Altach. A striker, Klos ...

, (born 1978 in Opole) professional footballer, Germany national football team

The Germany national football team (german: link=no, Deutsche Fußballnationalmannschaft) represents Germany in men's international football and played its first match in 1908. The team is governed by the German Football Association (''Deutsch ...

and FIFA World Cup

The FIFA World Cup, often simply called the World Cup, is an international association football competition contested by the senior men's national teams of the members of the ' ( FIFA), the sport's global governing body. The tournament has ...

all-time top goalscorer, and former striker for Italian football club S.S. Lazio

Società Sportiva Lazio (; ; ''Lazio Sport Club''), commonly referred to as Lazio, is an Italian professional sports club based in Rome, most known for its football activity. The society, founded in 1900, plays in the Serie A and have spe ...

.

* Maximilian Kolbe

Maximilian Maria Kolbe (born Raymund Kolbe; pl, Maksymilian Maria Kolbe; 1894–1941) was a Polish Catholic priest and Conventual Franciscan friar who volunteered to die in place of a man named Franciszek Gajowniczek in the German death ca ...

, (1894 in Zduńska Wola – 1941 in Auschwitz) a Polish Conventual Franciscan

The Order of Friars Minor Conventual (OFM Conv) is a male religious fraternity in the Roman Catholic Church that is a branch of the Franciscans. The friars in OFM CONV are also known as Conventual Franciscans, or Minorites.

Dating back to ...

friar, executed and subsequently canonised

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

.

* Henryk Korowicz, (1888 in Malinówka – 1941 in Lwów) professor, economist, and rector of Academy of Foreign Trade in Lwów.

* Janusz Korwin-Mikke

Janusz Ryszard Korwin-Mikke (; born 27 October 1942), also known by his initials JKM or simply as Korwin, is a Polish far-right politician, paleolibertarian and author. He was a member of the European Parliament from 2014 until 2018. He was the ...

, (born 1942 in Warsaw) controversial politician and writer.

* Gustaf Kossinna

Gustaf Kossinna (28 September 1858 – 20 December 1931) was a German philologist and archaeologist who was Professor of German Archaeology at the University of Berlin.

Along with Carl Schuchhardt he was the most influential German prehistor ...

, (1858 in Tilsit – 1931 in Berlin) linguist and archaeologist.

* Juliusz Karol Kunitzer, (1843 in Przedbórz – 1905 in Łódź) industrialist, economic activist and industrial magnate in Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

.

* Karolina Lanckorońska, (1898 in Gars am Kamp — 2002 in Rome) like her father, ( Count Karol Lanckoroński) an art collector and philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

.

* Joachim Lelewel

Joachim Lelewel (22 March 1786 – 29 May 1861) was a Polish historian, geographer, bibliographer, polyglot and politician.

Life

Born in Warsaw to a Polonized German family, Lelewel was educated at the Imperial University of Vilna, where in 18 ...

, (1786 in Warsaw – 1861 in Paris) a Polish historian and politician.

* Samuel Linde, (1771 in Toruń – 1847 in Warsaw) linguist, librarian and lexicographer of the Polish language.

* Tadeusz Manteuffel

Tadeusz Manteuffel or Tadeusz Manteuffel-Szoege (1902–1970) was a Polish historian, specializing in the medieval history of Europe.

Manteuffel was born in Rēzekne, Vitebsk Governorate, Russian Empire (now Latvia). His brothers were Leo ...

, (1902 in Rēzekne – 1970 in Warsaw) historian.

* Suzanna von Nathusius, (born in 2000) child actor.

* Wilhelm Orlik-Rückemann, (1894 in Lviv – 1986 in Ottawa) Polish general and military commander.

* Emilia Plater

Countess Emilia Broel-Plater ( lt, Emilija Pliaterytė; 13 November 1806 – 23 December 1831) was a Polish-Lithuanian (adjective), Polish–Lithuanian szlachta, noblewoman and revolutionary from the lands of the partitions of Poland, partitione ...

, (1806 in Vilnius – 1831 in Vainežeris) noblewoman and revolutionary.

* Lukas Podolski

Lukas Josef Podolski (; born Łukasz Józef Podolski, , on 4 June 1985) is a German professional footballer who plays as a forward for Ekstraklasa club Górnik Zabrze. Known for his powerful and accurate left foot, he is known for his explosive ...

(born 1985 in Gliwice) a German professional footballer who plays for Górnik Zabrze

Górnik Zabrze Spółka Akcyjna, commonly referred to as Górnik Zabrze S.A. or simply Górnik Zabrze (), is a Polish football club from Zabrze. Górnik is one of the most successful Polish football clubs in history, winning the second-most Pol ...

* Nelli Rokita, (born 1957 in Chelyabinsk) politician of Law and Justice

Law and Justice ( pl, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość , PiS) is a right-wing populist and national-conservative political party in Poland. Its chairman is Jarosław Kaczyński.

It was founded in 2001 by Jarosław and Lech Kaczyński as a direct su ...

party in Poland.

* Piotr Steinkeller, (1799 in Krakow - 1854 in Krakow) early industrialist and banker

* Jerzy Stuhr

Jerzy Oskar Stuhr (; born 18 April 1947) is a Polish film and theatre actor. He is one of the most popular, influential and versatile Polish actors. He also works as a screenwriter, film director and drama professor. He served as the Rector of t ...

, (born 1947 in Krakow) film actor and director retrieved 17 April 2020

January Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

* Donald Tusk

Donald Franciszek Tusk ( , ; born 22 April 1957) is a Polish politician who was President of the European Council from 2014 to 2019. He served as the 14th Prime Minister of Poland from 2007 to 2014 and was a co-founder and leader of the Civic P ...

, (born 1957 in Gdańsk) former Prime Minister of Poland

The President of the Council of Ministers ( pl, Prezes Rady Ministrów, lit=Chairman of the Council of Ministers), colloquially referred to as the prime minister (), is the head of the cabinet and the head of government of Poland. The responsi ...

, former President of the European Council

The president of the European Council is the person presiding over and driving forward the work of the European Council on the world stage. This institution comprises the college of heads of state or government of EU member states as well as t ...

.

* Jozef Unrug, (1884 in Brandenburg an der Havel – 1973 in Lailly-en-Val) Prussian-born Polish admiral who helped to form the Polish Navy in independent Poland, inmate of Colditz

Colditz () is a small town in the district of Leipzig, in Saxony, Germany. It is best known for Colditz Castle, the site of the Oflag IV-C POW camp for officers in World War II.

Geography

Colditz is situated in the Leipzig Bay, southeast of th ...

.

* Karol Ernest Wedel, (1813–1902) notable confectioner

Confectionery is the art of making confections, which are food items that are rich in sugar and carbohydrates. Exact definitions are difficult. In general, however, confectionery is divided into two broad and somewhat overlapping categories ...

.

* Edward Werner, (1878 in Warsaw – 1945 in New York City) economist, judge and politician in the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First Worl ...

.

German media in Poland

* Schlesisches Wochenblatt * Polen-Rundschau * Schlesien Aktuell – a German-language radio station fromOpole

Opole (; german: Oppeln ; szl, Ôpole) ;

* Silesian:

** Silesian PLS alphabet: ''Ôpole''

** Steuer's Silesian alphabet: ''Uopole''

* Silesian German: ''Uppeln''

* Czech: ''Opolí''

* Latin: ''Oppelia'', ''Oppolia'', ''Opulia'' is a city lo ...

* Polskie Radio

Polskie Radio Spółka Akcyjna (PR S.A.; English: Polish Radio) is Poland's national public-service radio broadcasting organization owned by the State Treasury of Poland.

History

Polskie Radio was founded on 18 August 1925 and began mak ...

– public-service radio with online German edition (Deutsche Redaktion), as well as broadcasts in German

* Polen am Morgen – online newspaper

An online newspaper (or electronic news or electronic news publication) is the online version of a newspaper, either as a stand-alone publication or as the online version of a printed periodical.

Going online created more opportunities for newsp ...

, published daily since 1998

See also

*Waldemar Kraft

Waldemar Kraft (19 February 1898 – 12 July 1977) was a German politician. A member of the SS in Nazi Germany, he served as Managing Director of the Reich Association for Land Management in the Annexed Territories from 1940 to 1945, administeri ...

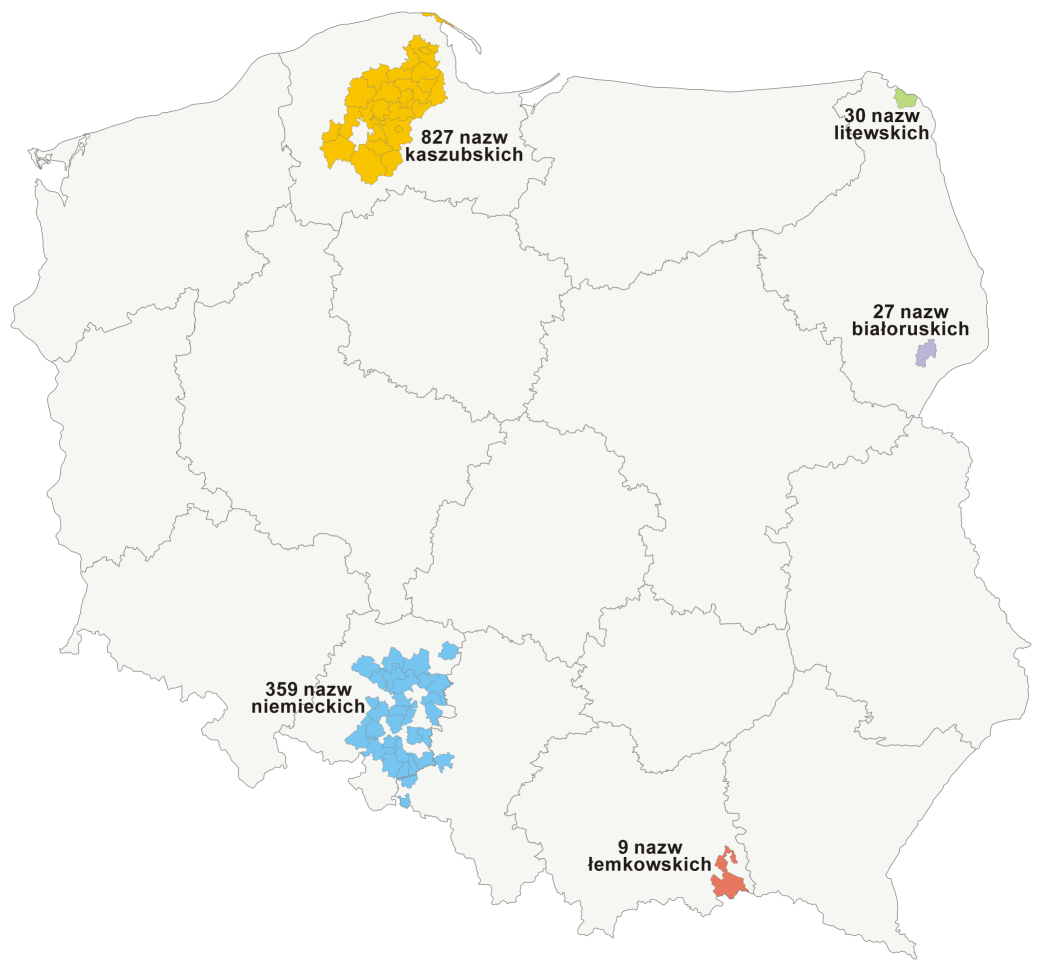

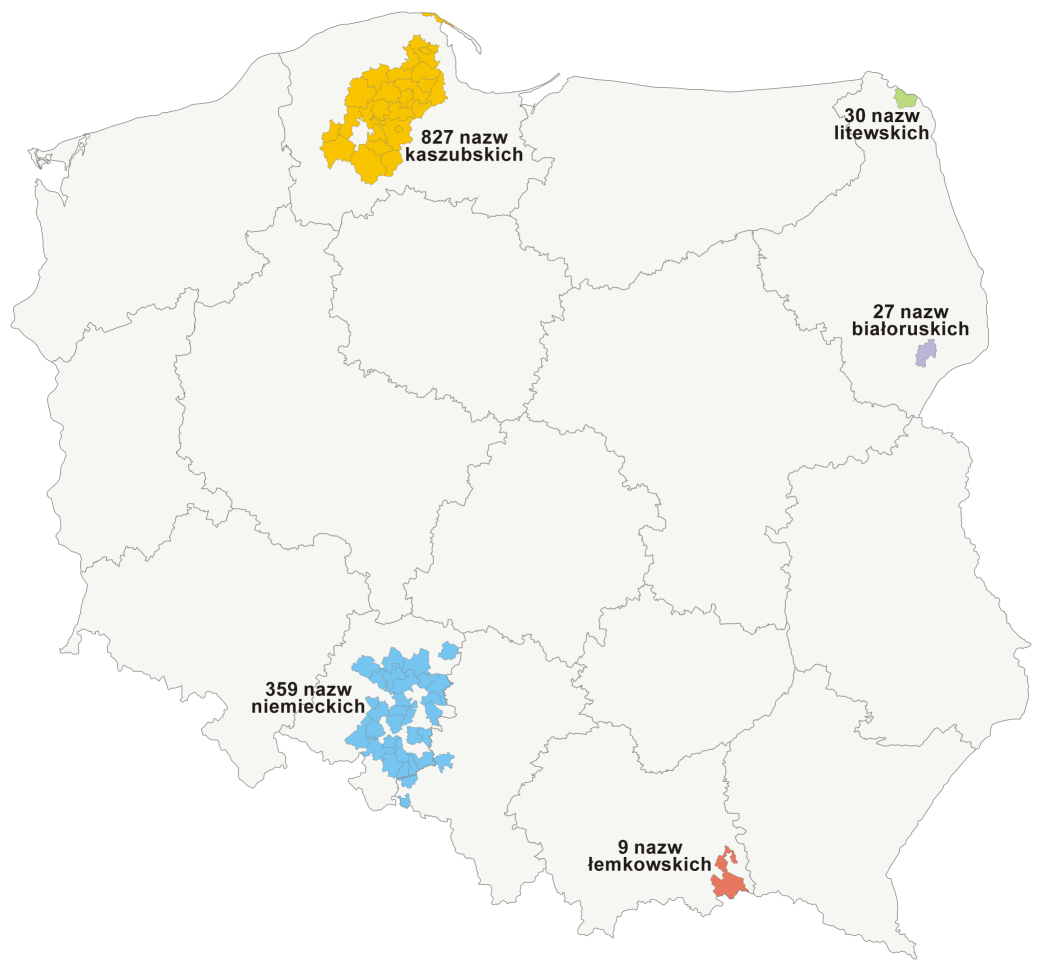

* Bilingual communes in Poland

The bilingual status of gminas (municipalities) in Poland is regulated by the ''Act of 6 January 2005 on National and Ethnic Minorities and on the Regional Languages'', which permits certain gminas with significant linguistic minorities to introdu ...

* German Minority (political party)

The German Minority Electoral Committee ( pl, Komitet Wyborczy Mniejszość Niemiecka, german: Wahlkomitee der Deutschen Minderheit) is an electoral committee in Poland, that represents the German minority. Since 2008, its representative has ...

* Germans in the Czech Republic

* Polish minority in Germany

Poles in Germany are the second largest Polish diaspora (''Polonia'') in the world and the biggest in Europe. Estimates of the number of Poles living in Germany vary from 2 million to about 3 million people living that might be of Polish descen ...

* Olędrzy

* Vistula Germans in Russian Poland

* Bambrzy

* Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of ''volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

Notes

References

*Dual Citizenship in Opole Silesia in the Context of European Integration

', Tomasz Kamusella, Opole University, in ''Facta Universitatis'', series Philosophy, Sociology and Psychology, Vol 2, No 10, 2003, pp. 699–716 * * *

Further reading

* de Zayas, Alfred M.: Die deutschen Vertriebenen. Graz, 2006. . * de Zayas, Alfred M.: Heimatrecht ist Menschenrecht. München, 2001.. * de Zayas, Alfred M.: A terrible Revenge. New York, 1994. . * de Zayas, Alfred M.: Nemesis at Potsdam. London, 1977. . * de Zayas, Alfred M.: 50 Thesen zur Vertreibung. München, 2008. . * Douglas, R.M.: Orderly and Humane. The Expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War. Yale University Press. . * Kleineberg A., Marx, Ch., Knobloch E., Lelgemann D.: Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung vo Ptolemaios: "Atlas der Oikumene". Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2010. * Matelski Dariusz, Niemcy w Polsce w XX wieku (Deutschen in Polen im 20. Jahrhundert), Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa-Poznań 1999. * Matelski Dariusz, Niemcy w II Rzeczypospolitej (1918-1939) ie Deutschen in der Zweiten Republik Polen (1918-1939) Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Toruń 2018 cz. 1 d. 1(), ss. 611, il., mapy. * Matelski Dariusz, Niemcy w II Rzeczypospolitej (1918-1939 ie Deutschen in der Zweiten Republik Polen (1918-1939), Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Toruń 2018 cz. 2 d. 1 (), ss. 624, Abstract (s. 264–274), Zusammenfassung (s. 275–400). * Naimark, Norman: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge Harvard Press, 2001. * Prauser, Steffen and Rees, Arfon: The Expulsion of the "German" Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War. Florence, Italy, European University Institute, 2004. * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:German Minority In Poland Germany–Poland relationsPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...