German (, ) is a

West Germanic language

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages). The West Germanic branch is classically subdivided ...

in the

Indo-European language family

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

, mainly spoken in

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. It is the majority and

official

An official is someone who holds an office (function or Mandate (politics), mandate, regardless of whether it carries an actual Office, working space with it) in an organization or government and participates in the exercise of authority (eithe ...

(or co-official) language in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

,

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

,

Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, and

Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a Landlocked country#Doubly landlocked, doubly landlocked Swiss Standard German, German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east ...

. It is also an official language of

Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

and the Italian autonomous province of

South Tyrol

South Tyrol ( , ; ; ), officially the Autonomous Province of Bolzano – South Tyrol, is an autonomous administrative division, autonomous provinces of Italy, province in northern Italy. Together with Trentino, South Tyrol forms the autonomo ...

, as well as a recognized

national language

'' ''

A national language is a language (or language variant, e.g. dialect) that has some connection— de facto or de jure—with a nation. The term is applied quite differently in various contexts. One or more languages spoken as first languag ...

in

Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

. There are also notable German-speaking communities in other parts of Europe, including:

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

(

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

), the

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

(

North Bohemia

North Bohemia (, ) is a region in the north of the Czech Republic.

Location

North Bohemia roughly covers the present-day NUTS regional unit of ''CZ04 Severozápad'' and the western part of ''CZ05 Severovýchod''.

From an administrative perspec ...

),

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

(

North Schleswig

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

),

Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

(

Krahule

Krahule (; , until 1890: ) is a village in Žiar nad Hronom District in the Banská Bystrica Region of central Slovakia. It is the only municipality in Slovakia that officially uses German along with Slovak.

History

The town was first mentione ...

),

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

,

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

(

Sopron

Sopron (; , ) is a city in Hungary on the Austrian border, near Lake Neusiedl/Lake Fertő.

History

Ancient times-13th century

In the Iron Age a hilltop settlement with a burial ground existed in the neighbourhood of Sopron-Várhely.

When ...

), and

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

(

Alsace

Alsace (, ; ) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in the Grand Est administrative region of northeastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine, next to Germany and Switzerland. In January 2021, it had a population of 1,9 ...

). Overseas, sizeable communities of German-speakers are found in the Americas.

German is one of the

major languages of the world, with nearly 80 million native speakers and over 130 million total speakers as of 2024. It is the most spoken native language within the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

. German is the second-most widely spoken

Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

, after English, both as a

first

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and as a

second language

A second language (L2) is a language spoken in addition to one's first language (L1). A second language may be a neighbouring language, another language of the speaker's home country, or a foreign language.

A speaker's dominant language, which ...

. German is also widely taught as a

foreign language

A foreign language is a language that is not an official language of, nor typically spoken in, a specific country. Native speakers from that country usually need to acquire it through conscious learning, such as through language lessons at schoo ...

, especially in

continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

(where it is the third most taught foreign language after English and French) and in the United States (where it is the third

most commonly learned second language in K-12 education and among the most studied foreign languages in higher education after Spanish and French).

Overall, German is the fourth most commonly learned second language globally. The language has been influential in the fields of philosophy, theology, science, and technology. It is the second most commonly used

language in science and the

third most widely used language on websites.

The

German-speaking countries

The following is a list of the countries and territories where German is an official language (also known as the Germanosphere). It includes countries that have German as (one of) their nationwide official language(s), as well as dependent ter ...

are ranked fifth in terms of annual publication of new books, with one-tenth of all books (including e-books) in the world being published in German.

German is most closely related to other West Germanic languages, namely

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

,

Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

,

English, the

Frisian languages

The Frisian languages ( or ) are a closely related group of West Germanic languages, spoken by about 400,000 Frisian people, who live on the southern fringes of the North Sea in the Netherlands and Germany. The Frisian languages are the closes ...

, and

Scots. It also contains close similarities in vocabulary to some languages in the

North Germanic group, such as

Danish,

Norwegian, and

Swedish. Modern German gradually developed from

Old High German

Old High German (OHG; ) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally identified as the period from around 500/750 to 1050. Rather than representing a single supra-regional form of German, Old High German encompasses the numerous ...

, which in turn developed from

Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages, Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from ...

during the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

.

German is an

inflected language

Fusional languages or inflected languages are a type of synthetic language, distinguished from agglutinative languages by their tendency to use single inflectional morphemes to denote multiple grammatical, syntactic, or semantic features.

For e ...

, with four

cases for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative); three

genders

Gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender. Although gender often corresponds to sex, a transgender person may identify with a gender other than the ...

(masculine, feminine, neuter) and two

numbers

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

(singular, plural). It has

strong and weak verbs. The majority of its vocabulary derives from the ancient Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, while a smaller share is partly derived from

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, along with fewer words borrowed from

French and

Modern English

Modern English, sometimes called New English (NE) or present-day English (PDE) as opposed to Middle and Old English, is the form of the English language that has been spoken since the Great Vowel Shift in England

England is a Count ...

. English, however, is the main source of more recent

loanword

A loanword (also a loan word, loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language (the recipient or target language), through the process of borrowing. Borrowing is a metaphorical term t ...

s.

German is a

pluricentric language

A pluricentric language or polycentric language is a language with several codified standard forms, often corresponding to different countries. Many examples of such languages can be found worldwide among the most-spoken languages, including but n ...

; the three standardized variants are

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

,

Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example:

** Austria-Hungary

** Austria ...

, and

Swiss Standard German

Swiss Standard German (SSG; ), or Swiss High German ( or ; ), referred to by the Swiss as , or , is the written form of one (German language, German) of four languages of Switzerland, national languages in Switzerland, besides French language, Fr ...

.

Standard German

Standard High German (SHG), less precisely Standard German or High German (, , or, in Switzerland, ), is the umbrella term for the standard language, standardized varieties of the German language, which are used in formal contexts and for commun ...

is sometimes called ''

High German

The High German languages (, i.e. ''High German dialects''), or simply High German ( ) – not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called "High German" – comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Ben ...

'', which refers to its regional origin. German is also notable for

its broad spectrum of dialects, with many varieties existing in Europe and other parts of the world. Some of these non-standard varieties have become recognized and protected by regional or national governments.

Since 2004,

heads of state of the German-speaking countries have met every year,

and the

Council for German Orthography

The (, "Council for German Orthography" or "Council for German Spelling"), or , is the main international body regulating Standard High German orthography.

With its seat being in Mannheim, Germany, the RdR was formed in 2004 as a successor to ...

has been the main international body regulating

German orthography

German orthography is the orthography used in writing the German language, which is largely phonemic. However, it shows many instances of spellings that are historic or analogous to other spellings rather than phonemic. The pronunciation of al ...

.

Classification

German is an

Indo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia ( ...

that belongs to the

West Germanic

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic languages, Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic languages, North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages, East Germ ...

group of the

Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoke ...

. The Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three branches:

North Germanic

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also r ...

,

East Germanic

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that eas ...

, and

West Germanic

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic languages, Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic languages, North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages, East Germ ...

. The first of these branches survives in modern

Danish,

Swedish,

Norwegian,

Faroese, and

Icelandic, all of which are descended from

Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and

Gothic is the only language in this branch which survives in written texts. The West Germanic languages, however, have undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as English, German,

Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

,

Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

,

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

, and others.

Within the West Germanic language dialect continuum, the

Benrath and

Uerdingen

Uerdingen () is a district of the city of Krefeld, Germany, with a population of 17,888 (2019). Originally a separate city in its own right, Uerdingen merged with the city of Krefeld in 1929. Today, Uerdingen is best known for a local distillery ...

lines (running through

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in the state after Cologne and the List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants, seventh-largest city ...

-

Benrath and

Krefeld

Krefeld ( , ; ), also spelled Crefeld until 1925 (though the spelling was still being used in British papers throughout the Second World War), is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, in western Germany. It is located northwest of Düsseldorf, its c ...

-

Uerdingen

Uerdingen () is a district of the city of Krefeld, Germany, with a population of 17,888 (2019). Originally a separate city in its own right, Uerdingen merged with the city of Krefeld in 1929. Today, Uerdingen is best known for a local distillery ...

, respectively) serve to distinguish the Germanic dialects that were affected by the

High German consonant shift

In historical linguistics, the High German consonant shift or second Germanic consonant shift is a phonological development (sound change) that took place in the southern parts of the West Germanic languages, West Germanic dialect continuum. The ...

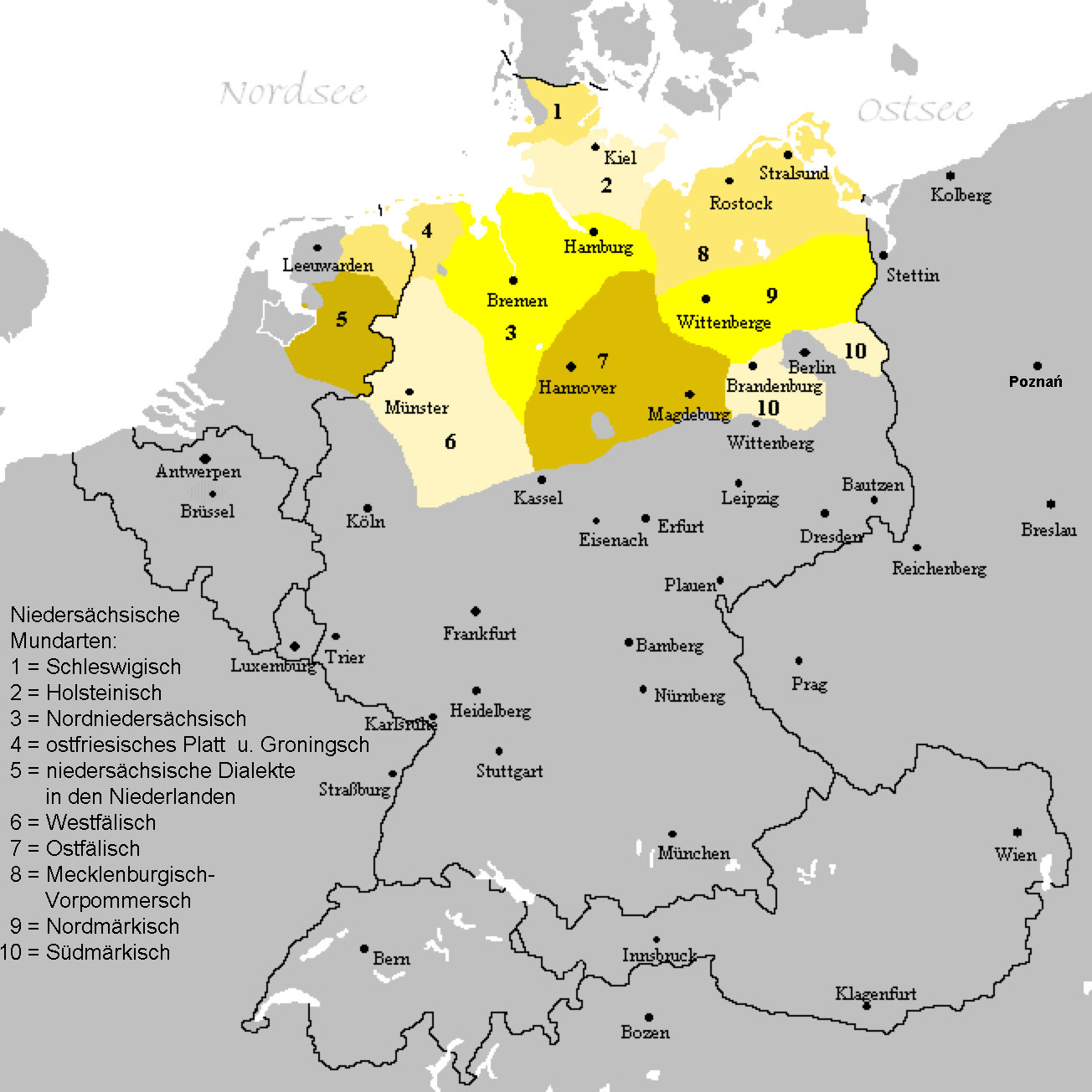

(south of Benrath) from those that were not (north of Uerdingen). The various regional dialects spoken south of these lines are grouped as

High German

The High German languages (, i.e. ''High German dialects''), or simply High German ( ) – not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called "High German" – comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Ben ...

dialects, while those spoken to the north comprise the

Low German

Low German is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language variety, language spoken mainly in Northern Germany and the northeastern Netherlands. The dialect of Plautdietsch is also spoken in the Russian Mennonite diaspora worldwide. "Low" ...

and

Low Franconian

In historical linguistics, historical and comparative linguistics, Low Franconian is a linguistic category used to classify a number of historical and contemporary West Germanic languages, West Germanic Variety (linguistics), varieties closely r ...

dialects. As members of the West Germanic language family, High German, Low German, and Low Franconian have been proposed to be further distinguished historically as

Irminonic

Elbe Germanic, also called Irminonic or Erminonic, is a proposed subgrouping of West Germanic languages introduced by the German linguist Friedrich Maurer (1898–1984) in his book, ''Nordgermanen und Alemanen'', to describe the West Germanic d ...

,

Ingvaeonic

North Sea Germanic, also known as Ingvaeonic ( ), is a subgrouping of West Germanic languages that consists of Old Frisian, Old English, and Old Saxon, and their descendants. These languages share a number of commonalities, such as a single pl ...

, and

Istvaeonic, respectively. This classification indicates their historical descent from dialects spoken by the Irminones (also known as the Elbe group), Ingvaeones (or North Sea Germanic group), and Istvaeones (or Weser–Rhine group).

Standard German

Standard High German (SHG), less precisely Standard German or High German (, , or, in Switzerland, ), is the umbrella term for the standard language, standardized varieties of the German language, which are used in formal contexts and for commun ...

is based on a combination of

Thuringian

Thuringian is an East Central German dialect group spoken in much of the modern German Free State of Thuringia north of the Rennsteig ridge, southwestern Saxony-Anhalt and adjacent territories of Hesse and Bavaria. It is close to Upper Saxon s ...

-

Upper Saxon

Upper Saxon (, , ) is an East Central German dialect spoken in much of the modern German state of Saxony and in adjacent parts of southeastern Saxony-Anhalt and eastern Thuringia. As of the early 21st century, it is mostly extinct and a new r ...

and Upper Franconian dialects, which are

Central German

Central German or Middle German () is a group of High German languages spoken from the Rhineland in the west to the former eastern territories of Germany.

Central German divides into two subgroups, West Central German and East Central Ger ...

and Upper German dialects belonging to the

High German

The High German languages (, i.e. ''High German dialects''), or simply High German ( ) – not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called "High German" – comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Ben ...

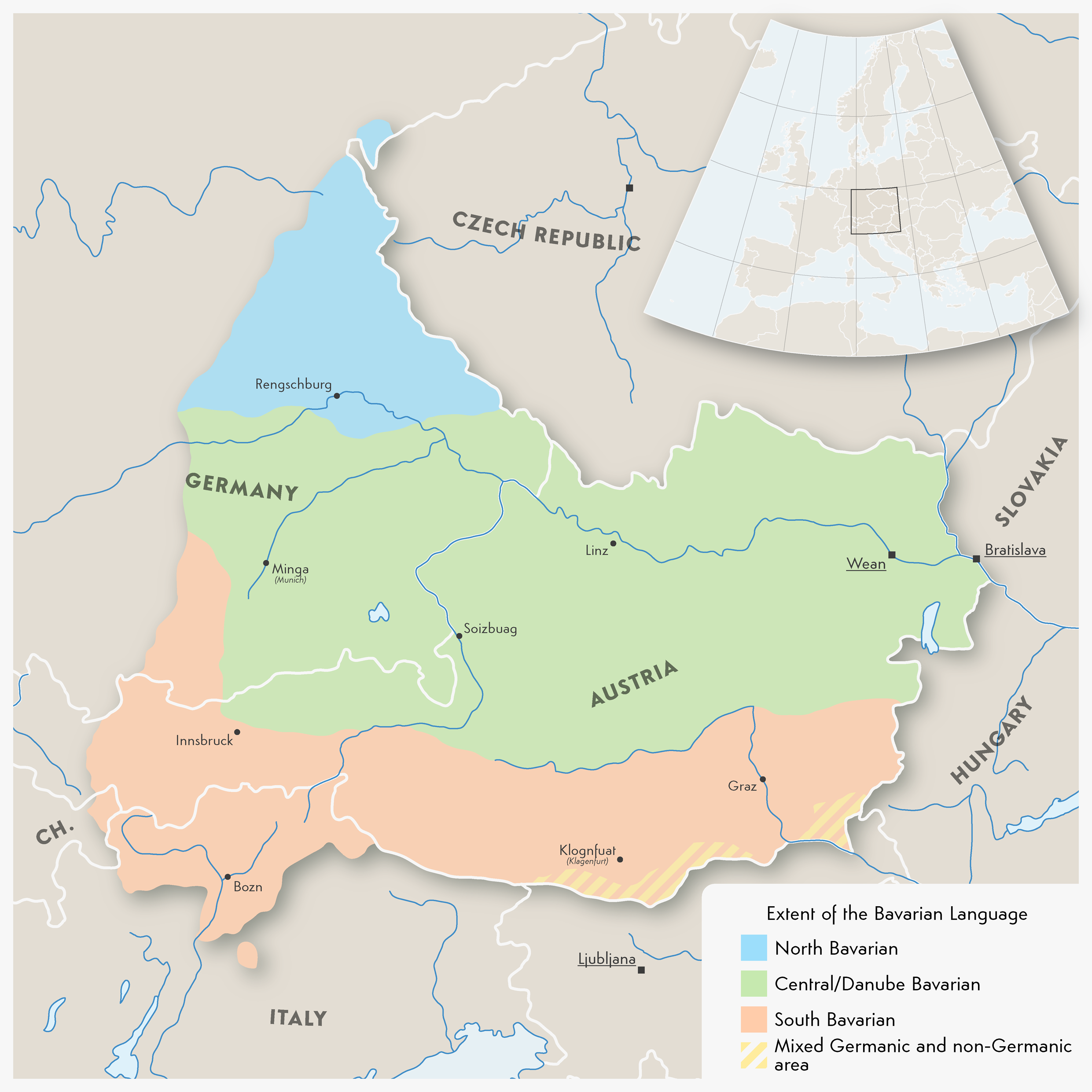

dialect group. German is therefore closely related to the other languages based on High German dialects, such as

Luxembourgish

Luxembourgish ( ; also ''Luxemburgish'', ''Luxembourgian'', ''Letzebu(e)rgesch''; ) is a West Germanic language that is spoken mainly in Luxembourg. About 400,000 people speak Luxembourgish worldwide.

The language is standardized and officiall ...

(based on

Central Franconian dialects

Central or Middle Franconian () refers to the following continuum of West Central German dialects:

* Ripuarian (spoken in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, in eastern Belgium, and the southeastern tip of Dutch Limburg)

* Moselle Fr ...

) and

Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

. Also closely related to Standard German are the

Upper German

Upper German ( ) is a family of High German dialects spoken primarily in the southern German-speaking area ().

History

In the Old High German time, only Alemannic and Bairisch are grouped as Upper German. In the Middle High German time, East F ...

dialects spoken in the southern

German-speaking countries

The following is a list of the countries and territories where German is an official language (also known as the Germanosphere). It includes countries that have German as (one of) their nationwide official language(s), as well as dependent ter ...

, such as

Swiss German

Swiss German (Standard German: , ,Because of the many different dialects, and because there is no #Conventions, defined orthography for any of them, many different spellings can be found. and others; ) is any of the Alemannic German, Alemannic ...

(

Alemannic dialects

Alemannic, or rarely Alemannish (''Alemannisch'', ), is a group of High German dialects. The name derives from the ancient Germanic tribal confederation known as the Alemanni ("all men").

Distribution

Alemannic dialects are spoken by approxi ...

) and the various Germanic dialects spoken in the French

region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

of

Grand Est

Grand Est (; ) is an Regions of France, administrative region in northeastern France. It superseded three former administrative regions, Alsace, Champagne-Ardenne and Lorraine, on 1 January 2016 under the provisional name of Alsace-Champagne-A ...

, such as

Alsatian (mainly Alemannic, but also Centraland

Upper Franconian

High Franconian or Upper Franconian () is a part of High German consisting of East Franconian and South Franconian.Noble, Cecil A. M. (1983). ''Modern German Dialects.'' New York / Berne / Frankfort on the Main, Peter Lang, p. 119. It is spoke ...

dialects) and

Lorraine Franconian

Lorraine Franconian ( native name: or ; or '; ) is an ambiguous designation for dialects of West Central German (), a group of High German dialects spoken in the Moselle department of the former northeastern French region of Lorraine (See ...

(Central Franconian).

After these High German dialects, standard German is less closely related to languages based on Low Franconian dialects (e.g., Dutch and Afrikaans), Low German or Low Saxon dialects (spoken in northern Germany and southern

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

), neither of which underwent the High German consonant shift. As has been noted, the former of these dialect types is Istvaeonic and the latter Ingvaeonic, whereas the High German dialects are all Irminonic; the differences between these languages and standard German are therefore considerable. Also related to German are the Frisian languages—

North Frisian (spoken in

Nordfriesland

Nordfriesland (; ; Low German: Noordfreesland), also known as North Frisia, is the northernmost Districts of Germany, district of Germany, part of the state of Schleswig-Holstein. It includes almost all of traditional North Frisia (with the e ...

),

Saterland Frisian (spoken in

Saterland

Saterland (; Saterland Frisian: , ) is a municipality in the district of Cloppenburg, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated between the cities of Leer, Cloppenburg, and Oldenburg. It is home to Saterland Frisians, who speak Frisian in addi ...

), and

West Frisian (spoken in

Friesland

Friesland ( ; ; official ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia (), named after the Frisians, is a Provinces of the Netherlands, province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen (p ...

)—as well as the Anglic languages of English and Scots. These

Anglo-Frisian

The Anglo-Frisian languages are a proposed sub-branch of the West Germanic languages encompassing the Anglic languages ( English, Scots, extinct Fingallian, and extinct Yola) as well as the Frisian languages ( North Frisian, East Frisian, ...

dialects did not take part in the High German consonant shift, and the Anglic languages also adopted much vocabulary from both

Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

and the

Norman language

Norman or Norman French (, , Guernésiais: , Jèrriais: ) is a ''Langues d'oïl, langue d'oïl'' spoken in the historical region, historical and Cultural area, cultural region of Normandy.

The name "Norman French" is sometimes also used to des ...

.

History

Old High German

The

history of the German language

The appearance of the German language begins in the Early Middle Ages with the High German consonant shift. Old High German, Middle High German, and Early New High German span the duration of the Holy Roman Empire. The 19th and 20th centuries s ...

begins with the

High German consonant shift

In historical linguistics, the High German consonant shift or second Germanic consonant shift is a phonological development (sound change) that took place in the southern parts of the West Germanic languages, West Germanic dialect continuum. The ...

during the

Migration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

, which separated Old High German dialects from

Old Saxon

Old Saxon (), also known as Old Low German (), was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Eur ...

. This

sound shift

In historical linguistics, a sound change is a change in the pronunciation of a language. A sound change can involve the replacement of one speech sound (or, more generally, one phonetic feature value) by a different one (called phonetic cha ...

involved a drastic change in the pronunciation of both

voiced

Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds (usually consonants). Speech sounds can be described as either voiceless (otherwise known as ''unvoiced'') or voiced.

The term, however, is used to refe ...

and voiceless

stop consonant

In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or simply a stop, is a pulmonic consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases.

The occlusion may be made with the tongue tip or blade (, ), tongue body (, ), lip ...

s (''b'', ''d'', ''g'', and ''p'', ''t'', ''k'', respectively). The primary effects of the shift were the following below.

* Voiceless stops became long (

geminated

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (; from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from ...

) voiceless

fricative

A fricative is a consonant produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate in ...

s following a vowel;

* Voiceless stops became

affricate

An affricate is a consonant that begins as a stop and releases as a fricative, generally with the same place of articulation (most often coronal). It is often difficult to decide if a stop and fricative form a single phoneme or a consonant pai ...

s in word-initial position, or following certain consonants;

* Voiced stops became voiceless in certain phonetic settings.

While there is written evidence of the

Old High German

Old High German (OHG; ) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally identified as the period from around 500/750 to 1050. Rather than representing a single supra-regional form of German, Old High German encompasses the numerous ...

language in several

Elder Futhark

The Elder Futhark (or Fuþark, ), also known as the Older Futhark, Old Futhark, or Germanic Futhark, is the oldest form of the runic alphabets. It was a writing system used by Germanic peoples for Northwest Germanic dialects in the Migration Per ...

inscriptions from as early as the sixth century AD (such as the

Pforzen buckle

The Pforzen buckle is a silver belt buckle found in Pforzen, Ostallgäu ( Schwaben) in 1992. The Alemannic grave in which it was found (no. 239) dates to the end of the 6th century and was presumably that of a warrior, as it also contained a spe ...

), the Old High German period is generally seen as beginning with the ''

Abrogans

''Abrogans'', also ''German Abrogans'' or ''Codex Abrogans'' (St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 911), is a Middle Latin–Old High German glossary, whose preserved copy in the Abbey Library of St Gall is regarded as the oldest preserved book in th ...

'' (written ), a Latin-German

glossary

A glossary (from , ''glossa''; language, speech, wording), also known as a vocabulary or clavis, is an alphabetical list of Term (language), terms in a particular domain of knowledge with the definitions for those terms. Traditionally, a gloss ...

supplying over 3,000 Old High German words with their

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

equivalents. After the ''Abrogans'', the first coherent works written in Old High German appear in the ninth century, chief among them being the ''

Muspilli

''Muspilli'' is an Old High German alliterative verse poem known in incomplete form (103 lines) from a ninth-century Bavarian manuscript. Its subject is the fate of the soul immediately after death and at the Last Judgment. Many aspects of the int ...

'',

Merseburg charms

The Merseburg charms, Merseburg spells, or Merseburg incantations () are two Middle Ages, medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic paganism, Germanic pagan belief prese ...

, and ', and other religious texts (the ''

Georgslied

The Georgslied (''Song of St. George'') is a set of poems and hymns to Saint George in Old High German.

Its likely origin is Saint George's Abbey on the Reichenau monastic island on Lake Constance in Germany, which was founded in 888 and was an ...

'', ''

Ludwigslied

The ''Ludwigslied'' (in English, ''Lay'' or ''Song of Ludwig'') is an Old High German (OHG) poem of 59 rhyming couplets, celebrating the victory of the Frankish army, led by Louis III of France, over Danish (Viking) raiders at the Battle of Sau ...

'', ''Evangelienbuch'', and translated hymns and prayers). The ''Muspilli'' is a Christian poem written in a

Bavarian dialect offering an account of the soul after the

Last Judgment

The Last Judgment is a concept found across the Abrahamic religions and the '' Frashokereti'' of Zoroastrianism.

Christianity considers the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to entail the final judgment by God of all people who have ever lived, res ...

, and the Merseburg charms are transcriptions of spells and charms from the

pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

Germanic tradition. Of particular interest to scholars, however, has been the ', a secular

epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

telling the tale of an estranged father and son unknowingly meeting each other in battle. Linguistically, this text is highly interesting due to the mixed use of

Old Saxon

Old Saxon (), also known as Old Low German (), was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Eur ...

and Old High German dialects in its composition. The written works of this period stem mainly from the

Alamanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River during the first millennium. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Roman emperor Caracalla of 213 CE, the Alemanni c ...

, Bavarian, and

Thuringian

Thuringian is an East Central German dialect group spoken in much of the modern German Free State of Thuringia north of the Rennsteig ridge, southwestern Saxony-Anhalt and adjacent territories of Hesse and Bavaria. It is close to Upper Saxon s ...

groups, all belonging to the Elbe Germanic group (

Irminones

The Irminones, also referred to as Herminones or Hermiones (), were a large group of early Germanic tribes settling in the Elbe watershed and by the first century AD expanding into Bavaria, Swabia, and Bohemia. Notably this included the large sub ...

), which had settled in what is now southern-central Germany and

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

between the second and sixth centuries, during the great migration.

In general, the surviving texts of Old High German (OHG) show a wide range of

dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

al diversity with very little written uniformity. The early written tradition of OHG survived mostly through

monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which m ...

and

scriptoria

A scriptorium () was a writing room in medieval European monasteries for the copying and Illuminated manuscript, illuminating of manuscripts by scribes.

The term has perhaps been over-used—only some monasteries had special rooms set aside for ...

as local translations of Latin originals; as a result, the surviving texts are written in highly disparate regional dialects and exhibit significant Latin influence, particularly in vocabulary. At this point monasteries, where most written works were produced, were dominated by Latin, and German saw only occasional use in official and ecclesiastical writing.

Middle High German

While there is no complete agreement over the dates of the

Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; or ; , shortened as ''Mhdt.'' or ''Mhd.'') is the term for the form of High German, High German language, German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High ...

(MHG) period, it is generally seen as lasting from 1050 to 1350. This was a period of significant expansion of the geographical territory occupied by Germanic tribes, and consequently of the number of German speakers. Whereas during the Old High German period the Germanic tribes extended only as far east as the

Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

and

Saale

The Saale (), also known as the Saxon Saale ( ) and Thuringian Saale (), is a river in Germany and a left-bank tributary of the Elbe. It is not to be confused with the smaller Fränkische Saale, Franconian Saale, a right-bank tributary of the M ...

rivers, the MHG period saw a number of these tribes expanding beyond this eastern boundary into

Slavic

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Slav ...

territory (known as the '). With the increasing wealth and geographic spread of the Germanic groups came greater use of German in the courts of nobles as the standard language of official proceedings and literature. A clear example of this is the ' employed in the

Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynast ...

court in

Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

as a standardized supra-dialectal written language. While these efforts were still regionally bound, German began to be used in place of Latin for certain official purposes, leading to a greater need for regularity in written conventions.

While the major changes of the MHG period were socio-cultural, High German was still undergoing significant linguistic changes in syntax, phonetics, and morphology as well (e.g.

diphthongization

In historical linguistics, vowel breaking, vowel fracture, or diphthongization is the sound change of a monophthong into a diphthong or triphthong.

Types

Vowel breaking may be unconditioned or conditioned. It may be triggered by the presence of ...

of certain vowel sounds: ' (OHG & MHG "house")''→ (regionally in later MHG)→'' (NHG), and weakening of unstressed short vowels to

schwa � ' (OHG "days")→' (MHG)).

A great wealth of texts survives from the MHG period. Significantly, these texts include a number of impressive secular works, such as the , an

epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

telling the story of the

dragon

A dragon is a Magic (supernatural), magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but European dragon, dragons in Western cultures since the Hi ...

-slayer

Siegfried

Siegfried is a German-language male given name, composed from the Germanic elements ''sig'' "victory" and ''frithu'' "protection, peace".

The German name has the Old Norse cognate ''Sigfriðr, Sigfrøðr'', which gives rise to Swedish ''Sigfrid' ...

(), and the ''

Iwein

''Iwein'' is a Middle High German verse romance by the poet Hartmann von Aue, written around 1200. An Arthurian tale freely adapted from Chrétien de Troyes' Old French ''Yvain, the Knight of the Lion">-4; we might wonder whether there's a poin ...

'', an

Arthurian

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a leader of the post-Ro ...

verse poem by

Hartmann von Aue

Hartmann von Aue, also known as Hartmann von Ouwe, (born ''c.'' 1160–70, died ''c.'' 1210–20) was a German knight and poet. With his works including '' Erec'', '' Iwein'', '' Gregorius'', and '' Der arme Heinrich'', he introduced the Arthu ...

(),

lyric poems, and courtly romances such as ''

Parzival

''Parzival'' () is a medieval chivalric romance by the poet and knight Wolfram von Eschenbach in Middle High German. The poem, commonly dated to the first quarter of the 13th century, centers on the Arthurian hero Parzival (Percival in English) ...

'' and ''

Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; ; ), also known as Tristran or Tristram and similar names, is the folk hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. While escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed Tristan's uncle, King Mark of ...

''. Also noteworthy is the ', the first book of laws written in

Middle ''Low'' German (). The abundance and especially the secular character of the literature of the MHG period demonstrate the beginnings of a standardized written form of German, as well as the desire of poets and authors to be understood by individuals on supra-dialectal terms.

The Middle High German period is generally seen as ending when the 1346–53

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

decimated Europe's population.

Early New High German

Modern High German begins with the Early New High German (ENHG) period, which

Wilhelm Scherer dates 13501650, terminating with the end of the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. This period saw the further displacement of Latin by German as the primary language of courtly proceedings and, increasingly, of literature in the

German states

The Federal Republic of Germany is a federation and consists of sixteen partly sovereign ''states''. Of the sixteen states, thirteen are so-called area-states ('Flächenländer'); in these, below the level of the state government, there is a ...

. While these states were still part of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, and far from any form of unification, the desire for a cohesive written language that would be understandable across the many German-speaking

principalities

A principality (or sometimes princedom) is a type of monarchical state or feudal territory ruled by a prince or princess. It can be either a sovereign state or a constituent part of a larger political entity. The term "principality" is often ...

and kingdoms was stronger than ever. As a spoken language German remained highly fractured throughout this period, with a vast number of often mutually incomprehensible

regional dialects being spoken throughout the German states; the invention of the

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

and the publication of

Luther's vernacular translation of the Bible in 1534, however, had an immense effect on standardizing German as a supra-dialectal written language.

The ENHG period saw the rise of several important cross-regional forms of

chancery

Chancery may refer to:

Offices and administration

* Court of Chancery, the chief court of equity in England and Wales until 1873

** Equity (law), also called chancery, the body of jurisprudence originating in the Court of Chancery

** Courts of e ...

German, one being ', used in the court of the

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Maximilian I, and the other being ', used in the

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony ( or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356 to 1806 initially centred on Wittenberg that came to include areas around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz. It was a ...

in the

Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg

The Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg () was a medieval duchy of the Holy Roman Empire centered at Wittenberg, which emerged after the dissolution of the stem duchy of Saxony. The Ascanian dukes prevailed in obtaining the Saxon electoral dignity until ...

.

Alongside these courtly written standards, the invention of the printing press led to the development of a number of printers' languages (') aimed at making printed material readable and understandable across as many diverse dialects of German as possible. The greater ease of production and increased availability of written texts brought about increased standardisation in the written form of German.

One of the central events in the development of ENHG was the publication of

Luther's translation of the Bible into High German (the

New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

was published in 1522; the

Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

was published in parts and completed in 1534).

Luther based his translation primarily on the ' of

Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

, spending much time among the population of Saxony researching the dialect so as to make the work as natural and accessible to German speakers as possible. Copies of Luther's Bible featured a long list of

glosses

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginal or interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collection of glosses is a ''glossar ...

for each region, translating words which were unknown in the region into the regional dialect. Luther said the following concerning his translation method:

Luther's translation of the Bible into High German was also decisive for the German language and its evolution from

Early New High German

Early New High German (ENHG) is a term for the period in the history of the German language generally defined, following Wilhelm Scherer, as the period 1350 to 1650, developing from Middle High German and into New High German.

The term is the ...

to modern Standard German.

The publication of Luther's Bible was a decisive moment in the

spread of literacy in early modern Germany,

and promoted the development of non-local forms of language and exposed all speakers to forms of German from outside their own area. With Luther's rendering of the Bible in the vernacular, German asserted itself against the dominance of Latin as a legitimate language for courtly, literary, and now ecclesiastical subject-matter. His Bible was ubiquitous in the German states: nearly every household possessed a copy. Nevertheless, even with the influence of Luther's Bible as an unofficial written standard, a widely accepted standard for written German did not appear until the middle of the eighteenth century.

Habsburg Empire

German was the language of commerce and government in the

Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

, which encompassed a large area of

Central and

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

. Until the mid-nineteenth century, it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. Its use indicated that the speaker was a merchant or someone from an urban area, regardless of nationality.

Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

() and

Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

(

Buda

Buda (, ) is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill (), which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and ...

, ), to name two examples, were gradually

Germanized

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people, and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In l ...

in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain. However, Prague had a large German-speaking population since the Middle Ages, as had Pressburg (Pozsony, now Bratislava), which was settled by Germans in the 10th century. Significant portions of Bohemia and Moravia, now part of the

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

, had become German-speaking during

Ostsiedlung

(, ) is the term for the Early Middle Ages, early medieval and High Middle Ages, high medieval migration of Germanic peoples and Germanisation of the areas populated by Slavs, Slavic, Balts, Baltic and Uralic languages, Uralic peoples; the ...

. During the Habsburg time, Budapest and cities like

Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

() or

Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

(), contained significant German minorities.

In the eastern provinces of

Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

,

Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

, and

Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

(), German was the predominant language not only in the larger towns—like (

Timișoara

Timișoara (, , ; , also or ; ; ; see #Etymology, other names) is the capital city of Timiș County, Banat, and the main economic, social and cultural center in Western Romania. Located on the Bega (Tisza), Bega River, Timișoara is consider ...

), (

Sibiu

Sibiu ( , , , Hungarian: ''Nagyszeben'', , Transylvanian Saxon: ''Härmeschtat'' or ''Hermestatt'') is a city in central Romania, situated in the historical region of Transylvania. Located some north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles th ...

), and (

Brașov

Brașov (, , ; , also ''Brasau''; ; ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Kruhnen'') is a city in Transylvania, Romania and the county seat (i.e. administrative centre) of Brașov County.

According to the 2021 Romanian census, ...

)—but also in many smaller localities in the surrounding areas.

Standardization

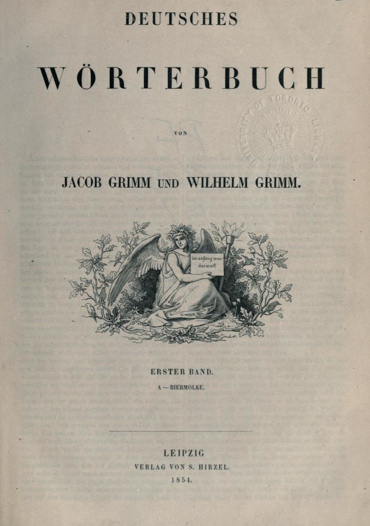

In 1901, the

Second Orthographic Conference ended with a (nearly) complete

standardization

Standardization (American English) or standardisation (British English) is the process of implementing and developing technical standards based on the consensus of different parties that include firms, users, interest groups, standards organiza ...

of the

Standard German

Standard High German (SHG), less precisely Standard German or High German (, , or, in Switzerland, ), is the umbrella term for the standard language, standardized varieties of the German language, which are used in formal contexts and for commun ...

language in its written form, and the Duden Handbook was declared its standard definition. Punctuation and compound spelling (joined or isolated compounds) were not standardized in the process.

The () by

Theodor Siebs

Theodor Siebs (; 26 August 1862 – 28 May 1941) was a German linguist most remembered today as the author of '' Deutsche Bühnenaussprache'' ('German stage pronunciation'), published in 1898. The work was largely responsible for setting the st ...

had established

conventions for German pronunciation in theatres, three years earlier; however, this was an artificial standard that did not correspond to any traditional spoken dialect. Rather, it was based on the pronunciation of German in Northern Germany, although it was subsequently regarded often as a general prescriptive norm, despite differing pronunciation traditions especially in the Upper-German-speaking regions that still characterise the dialect of the area todayespecially the pronunciation of the ending as

�kinstead of

�ç In Northern Germany, High German was a foreign language to most inhabitants, whose native dialects were subsets of Low German. It was usually encountered only in writing or formal speech; in fact, most of High German was a written language, not identical to any spoken dialect, throughout the German-speaking area until well into the 19th century. However, wider

standardization of pronunciation was established on the basis of public speaking in theatres and the media during the 20th century and documented in pronouncing dictionaries.

Official revisions of some of the rules from 1901 were not issued until the controversial

German orthography reform of 1996

The German orthography reform of 1996 (') was a change to German spelling and punctuation that was intended to simplify German orthography and thus to make it easier to learn, without substantially changing the rules familiar to users of the lan ...

was made the official standard by governments of all German-speaking countries. Media and written works are now almost all produced in Standard German which is understood in all areas where German is spoken.

Geographical distribution

As a result of the

German diaspora

The German diaspora (, ) consists of German people and their descendants who live outside of Germany. The term is used in particular to refer to the aspects of migration of German speakers from Central Europe to different countries around the ...

, as well as the popularity of German taught as a

foreign language

A foreign language is a language that is not an official language of, nor typically spoken in, a specific country. Native speakers from that country usually need to acquire it through conscious learning, such as through language lessons at schoo ...

,

the

geographical distribution of German speakers

This article details the geographical distribution of speakers of the German language, regardless of the legislative status within the countries where it is spoken. In addition to the Germanosphere () in Europe, German-speaking minorities are ...

(or "Germanophones") spans all inhabited continents.

However, an exact, global number of native German speakers is complicated by the existence of several varieties whose status as separate "languages" or "dialects" is disputed for political and linguistic reasons, including quantitatively strong varieties like certain forms of

Alemannic and

Low German

Low German is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language variety, language spoken mainly in Northern Germany and the northeastern Netherlands. The dialect of Plautdietsch is also spoken in the Russian Mennonite diaspora worldwide. "Low" ...

. With the inclusion or exclusion of certain varieties, it is estimated that approximately 9095 million people speak German as a

first language

A first language (L1), native language, native tongue, or mother tongue is the first language a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period hypothesis, critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' ...

, 1025million speak it as a

second language

A second language (L2) is a language spoken in addition to one's first language (L1). A second language may be a neighbouring language, another language of the speaker's home country, or a foreign language.

A speaker's dominant language, which ...

, and 75100million as a

foreign language

A foreign language is a language that is not an official language of, nor typically spoken in, a specific country. Native speakers from that country usually need to acquire it through conscious learning, such as through language lessons at schoo ...

.

This would imply the existence of approximately 175220million German speakers worldwide.

German sociolinguist

Ulrich Ammon estimated a number of 289 million German foreign language speakers without clarifying the criteria by which he classified a speaker.

Europe

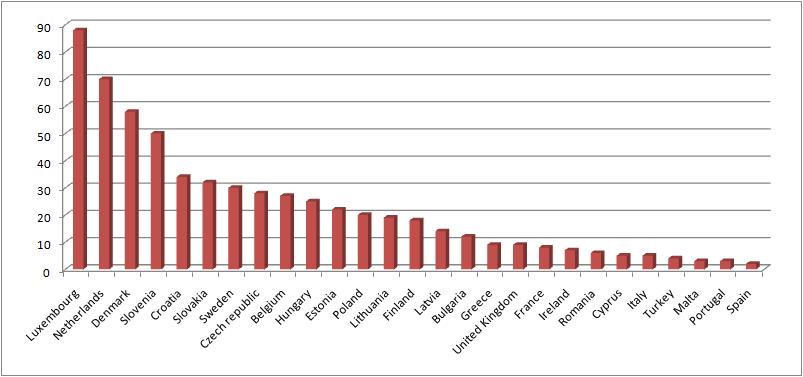

, about 90million people, or 16% of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

's population, spoke German as their mother tongue, making it the second most widely spoken language on the continent after Russian and the second biggest language in terms of overall speakers (after English), as well as the most spoken native language.

German Sprachraum

The area in central Europe where the majority of the population speaks German as a first language and has German as a (co-)official language is called the "German ''

Sprachraum

In linguistics, a sprachraum (; , "language area", plural sprachräume, ) is a geographical region where a common first language (mother tongue), with dialect varieties, or group of languages is spoken.

Characteristics

Many sprachräume are sep ...

''". German is the official language of the following countries:

*

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

*

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

*

17 cantons of

Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

*

Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a Landlocked country#Doubly landlocked, doubly landlocked Swiss Standard German, German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east ...

As a result of implemenation of the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

and ensuing expusion and ethnic cleansing in post-war Poland, the German Sprachraum significantly shrank, as well as by dissolution of the large German-speaking areas in Bohemia and Moravia. Former German-speaking exclaves of

East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, the

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (; ) was a city-state under the protection and oversight of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) and nearly 200 other small localities in the surrou ...

an the

Memelland ceased to exist, while

Francization

Francization (in American English, Canadian English, and Oxford English) or Francisation (in other British English), also known as Frenchification, is the expansion of French language use—either through willful adoption or coercion—by more an ...

in Alsace and Lorraine removed use of German in these areas.

German is a co-official language of the following countries:

*

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

(as majority language only in the

German-speaking Community

The German-speaking Community (, , DG), also known as East Belgium ( ), is one of the three federal communities of Belgium. The community is composed of nine municipalities in Liège Province, Wallonia, within the Eupen-Malmedy region in Easte ...

, which represents 0.7% of the Belgian population)

*

Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

, along with French and Luxembourgish

* Switzerland, co-official at the federal level with French, Italian, and Romansh, and at the local level in four

cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, th ...

:

Bern

Bern (), or Berne (), ; ; ; . is the ''de facto'' Capital city, capital of Switzerland, referred to as the "federal city".; ; ; . According to the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Confederation intentionally has no "capital", but Bern has gov ...

(with French),

Fribourg

or is the capital of the Cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Canton of Fribourg, Fribourg and district of Sarine (district), La Sarine. Located on both sides of the river Saane/Sarine, on the Swiss Plateau, it is a major economic, adminis ...

(with French),

Grisons

The Grisons (; ) or Graubünden (),Names include:

* ;

*Romansh language, Romansh:

**

**

**

**

**

**;

* ;

* ;

* .

See also list of European regions with alternative names#G, other names. more formally the Canton of the Grisons or the Canton ...

(with Italian and Romansh) and

Valais

Valais ( , ; ), more formally, the Canton of Valais or Wallis, is one of the cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of thirteen districts and its capital and largest city is Sion, Switzer ...

(with French)

* Italy, (as majority language only in the

Autonomous Province of South Tyrol, which represents 0.6% of the Italian population)

Outside the German Sprachraum

Although

expulsions and

(forced) assimilation after the two

World war

A world war is an international War, conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I ...

s greatly diminished them, minority communities of mostly bilingual German native speakers exist in areas both adjacent to and detached from the Sprachraum.

Within Europe, German is a recognized minority language in the following countries:

*

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

(see also:

Germans in the Czech Republic)

*

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

(see also:

North Schleswig Germans

Approximately 15,000 people in Denmark belong to an autochthonous ethnic German minority traditionally referred to as ''hjemmetyskere'', meaning "Home Germans" in Danish, and as ''Nordschleswiger'' in German. They are Danish citizens and m ...

)

*

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

(see also:

Germans of Hungary

German Hungarians (, ) are the ethnic German minority of Hungary, sometimes also called Danube Swabians (German: ''Donauschwaben'', Hungarian: ''dunai svábok''), many of whom call themselves "Shwoveh" in their own Swabian dialect. Danube Swab ...

)

*

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

(see also

German minority in Poland

The registered German minority in Poland (; ) is a group of German people that inhabit Poland, being the largest minority of the country. As of 2021, it had a population of 144,177.

The German language is spoken in certain areas in Opole Voiv ...

; German is an

auxiliary and co-official language in 31 communes)

*

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

(see also:

Germans of Romania

The Germans of Romania (; ; ) represent one of the most significant historical Minorities of Romania, ethnic minorities of Romania from the Modern era, modern period onwards.

Throughout Kingdom of Romania#The interbellum years, the interwar per ...

)

*

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

(see also:

Germans in Russia)

*

Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

(see also:

Carpathian Germans

Carpathian Germans (, or ''felvidéki németek'', , , ) are a group of Germans, ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe. The term was coined by the historian :de:Raimund Friedrich Kaindl, Raimund Friederich Kaindl (1866–1930), originally ...

)

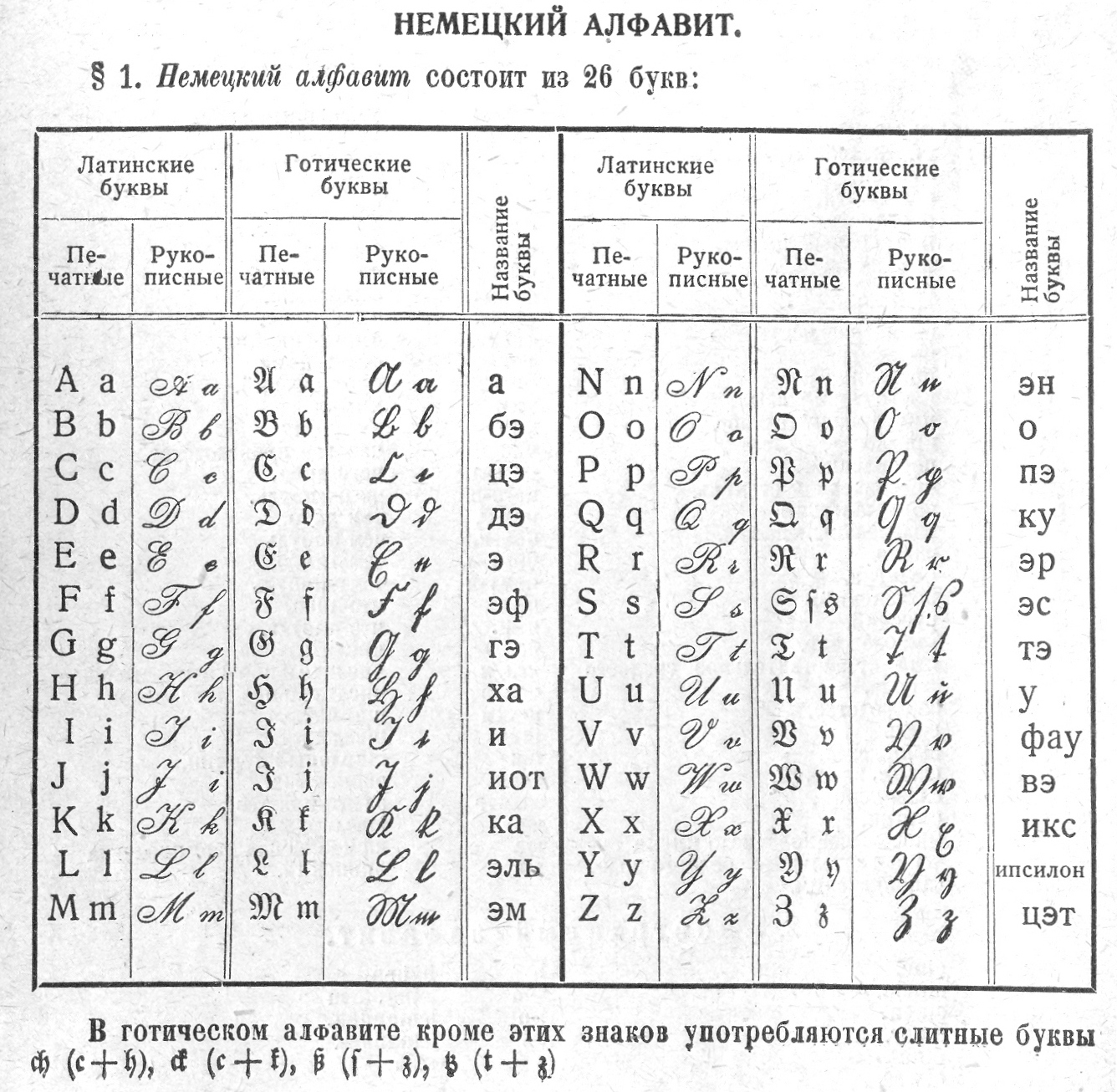

In France, the