George Washington Dixon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Washington Dixon (1801?Many biographies list his birth year as 1808, but Cockrell, ''Demons of Disorder'', 189, argues that 1801 is the correct date. This is based on Dixon's records at a New Orleans hospital, which list him as 60 years old in 1861, and a December 11, 1841 article in the ''Flash'' that says he was born "some forty years ago". – March 2, 1861) was an American singer, stage actor, and newspaper

Details about Dixon's childhood are scarce. The record suggests that he was born in

Details about Dixon's childhood are scarce. The record suggests that he was born in  Dixon performed through 1834, most frequently at New York's three major theatres. In addition to blackface song-and-dance numbers, he did whiteface songs and scenes from popular plays; much of his material was quite challenging. Dixon's fame allowed him to pepper his material with satire and political commentary. On November 25, 1830, he sang before a crowd of 120,000 in Washington, D.C., in support of the

Dixon performed through 1834, most frequently at New York's three major theatres. In addition to blackface song-and-dance numbers, he did whiteface songs and scenes from popular plays; much of his material was quite challenging. Dixon's fame allowed him to pepper his material with satire and political commentary. On November 25, 1830, he sang before a crowd of 120,000 in Washington, D.C., in support of the

The press reacted with its usual fervor:

The press reacted with its usual fervor:

On February 16, 1841, Dixon turned to a crusade against a New York

On February 16, 1841, Dixon turned to a crusade against a New York

editor

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, photographic, visual, audible, or cinematic material used by a person or an entity to convey a message or information. The editing process can involve correction, condensation, orga ...

. He rose to prominence as a blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

performer (possibly the first American to do so) after performing "Coal Black Rose

"Coal Black Rose" is a folk song, one of the earliest songs to be sung by a man in blackface. The man dressed as an overweight and overdressed black woman, who was found unattractive and masculine-looking. The song was first performed in the United ...

", " Zip Coon", and similar songs. He later turned to a career in journalism, during which he earned the enmity of members of the upper class for his frequent allegations against them.

At age 15, Dixon joined the circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclist ...

, where he quickly established himself as a singer. In 1829, he began performing "Coal Black Rose" in blackface; this and similar songs would propel him to stardom. In contrast to his contemporary Thomas D. Rice

Thomas Dartmouth Rice (May 20, 1808 – September 19, 1860) was an American performer and playwright who performed in blackface and used African American vernacular speech, song and dance to become one of the most popular minstrel show ente ...

, Dixon was primarily a singer rather than a dancer. He was by all accounts a gifted vocalist, and much of his material was quite challenging. "Zip Coon" became his trademark song.

By 1835, Dixon considered journalism to be his primary vocation. His first major paper was ''Dixon's Daily Review'', which he published from Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, in the United States. Alongside Cambridge, It is one of two traditional seats of Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in 2020, it was the fifth most populous city in Massachusetts as of ...

, in 1835. He followed this in 1836 with ''Dixon's Saturday Night Express'', published in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. By this point, he had taken to using his paper to expose what he considered the misdeeds of the upper classes. These stories earned him many enemies, and Dixon was taken to court on several occasions. His most successful paper was the ''Polyanthos'', which he began publishing in 1838 from New York City. Under its masthead, he challenged some of his greatest adversaries, including Thomas S. Hamblin, Reverend Francis L. Hawks

Francis Lister Hawks (June 10, 1798 – September 26, 1866) was an American writer, historian, educator and priest of the Episcopal Church. After practicing law with some distinction (and a brief stint as politician in North Carolina), Hawks bec ...

, and Madame Restell

Ann Trow Lohman (May 6, 1812 – April 1, 1878), better known as Madame Restell, was a British-born American abortion provider who practiced in New York City.

Early life

Ann Trow was born in Painswick, Gloucestershire, England in 1812 to John a ...

. After a brief foray into hypnotism, "pedestrianism" (long-distance walking), and other pursuits, he retired to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

.

Childhood, adolescence and young manhood

Details about Dixon's childhood are scarce. The record suggests that he was born in

Details about Dixon's childhood are scarce. The record suggests that he was born in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, probably in 1801, to a working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

family. He may have been educated at a charity school.Cockrell, ''Demons'', 96. Fairly detailed descriptions and portraits of Dixon survive; he had a swarthy complexion and a "splendid head of hair". However, the question of whether he was white or black is an open one. His enemies sometimes called him a "mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

", a "Negro

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

", or referred to him as "Zip Coon", the name of the black character in one of his songs. However, the weight of evidence suggests that if Dixon did have black ancestry, it was fairly remote.

A newspaper story from 1841 claims that at age 15, Dixon's singing caught the attention of a circus proprietor named West. The man convinced Dixon to join his traveling circus as a stablehand and errand boy. Dixon traveled with this and other circuses for a time, and he appears as a singer and reciter of poems on bills dated from as early as February 1824. By early 1829, he had taken on the epithet "The American Buffo Singer".

Over three days in late July 1829, Dixon performed "Coal Black Rose

"Coal Black Rose" is a folk song, one of the earliest songs to be sung by a man in blackface. The man dressed as an overweight and overdressed black woman, who was found unattractive and masculine-looking. The song was first performed in the United ...

" in blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

at the Bowery

The Bowery () is a street and neighborhood in Lower Manhattan in New York City. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th Street in the north.Jackson, Kenneth L. "B ...

, Chatham Garden, and Park

A park is an area of natural, semi-natural or planted space set aside for human enjoyment and recreation or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats. Urban parks are urban green space, green spaces set aside for recreation inside t ...

theatres in New York City. The ''Flash

Flash, flashes, or FLASH may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Fictional aliases

* Flash (DC Comics character), several DC Comics superheroes with super speed:

** Flash (Barry Allen)

** Flash (Jay Garrick)

** Wally West, the first Kid ...

'' characterized his audience as "crowded galleries and scantily filled boxes"; that is, mostly working-class. On September 24 at the Bowery, Dixon performed ''Love in a Cloud'', a dramatic interpretation of the events described in "Coal Black Rose" and possibly the first blackface farce

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical humor; the use of deliberate absurdity o ...

. These performances proved a hit, and Dixon rose to celebrity, perhaps before any other American blackface performer had done so.Watkins 84. On December 14, Dixon's benefit at the Albany Theatre

The Albany is a multi-purpose arts centre in Deptford, south-east London.

Facilities include a flexible performance space holding up to 300 seated or 500 standing and a bar, two studio theatres, a performance cafe and rehearsal / meeting rooms. T ...

grossed $155.87, the largest take there since the opening night earlier that year.

Dixon performed through 1834, most frequently at New York's three major theatres. In addition to blackface song-and-dance numbers, he did whiteface songs and scenes from popular plays; much of his material was quite challenging. Dixon's fame allowed him to pepper his material with satire and political commentary. On November 25, 1830, he sang before a crowd of 120,000 in Washington, D.C., in support of the

Dixon performed through 1834, most frequently at New York's three major theatres. In addition to blackface song-and-dance numbers, he did whiteface songs and scenes from popular plays; much of his material was quite challenging. Dixon's fame allowed him to pepper his material with satire and political commentary. On November 25, 1830, he sang before a crowd of 120,000 in Washington, D.C., in support of the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

in France. He began selling a collection of songs and skits he had popularized called ''Dixon's Oddities'' in 1830; the book remained in print long after. Dixon mostly played to a working-class audience, including in his repertoire such songs as "The New York Fireman", which compared firefighters to the American Founding Fathers. Oratory made up another facet of his act; on December 4, 1832, the ''Baltimore Patriot

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was d ...

'' reported that Dixon would read an address from the President at the Front Street Theatre

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

*The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ea ...

.

In 1833, he started a small newspaper called the Stonington ''Cannon''. However, the publication saw little success, and by January 1834, he was performing again, now with new talents, such as ventriloquism. Dixon seemed untarnished by his yearlong hiatus. Reviews said that "his voice seems formed of the music itself—'' 'it thrills'', it animates' ..." The ''Telegraph'' wrote,

Few Melodists have gained more celebrity or been so universally admired, ... The many effusions from the pen of this gentleman independent of his vocal powers, is sufficient proof of his being a man of considerable talent and originality—you should hear him sing his national air "on a wing that beamed in glory" nd it would beunnecessary for us to enlarge on his merits as a vocalist—for his Melodies display a feeling of Patriotism which attracts the attention of every beholder.In March, Dixon performed " Zip Coon" for the first time. Although Dixon had previously sung " Long Tail Blue", another racist tale about a black " dandy" trying to fit into Northern white society, "Zip Coon" garnered acclaim and quickly became an audience favorite and Dixon's trademark tune. He later claimed to have written the song, although others performed it before him, so this seems unlikely. Dixon accompanied his singing with an earthy

jig

The jig ( ga, port, gd, port-cruinn) is a form of lively folk dance in compound metre, as well as the accompanying dance tune. It is most associated with Irish music and dance. It first gained popularity in 16th-century Ireland and parts o ...

.

On July 7, the Farren Riots

Beginning July 7, 1834, New York City was torn by a huge antiabolitionist riot (also called Farren Riot or Tappan Riot) that lasted for nearly a week until it was put down by military force. "At times the rioters controlled whole sections of the ...

erupted. Young men in New York City targeted the homes, businesses, churches, and institutions of black New Yorkers and abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. On the night of July 9, the mob stormed the Bowery Theatre. Manager Thomas S. Hamblin failed to quell them, and actor Edwin Forrest did not meet their expectations when they ordered him to perform. According to the '' New York Sun'':

Mr. Dixon, the singer (an American,) now made his appearance. "Let us have Zip Coon," exclaimed a thousand voices. The singer gave them their favorite song, amidst peals of laughter,—and his Honor the Mayor, who as the old woman said of her husband, is a "good-natured, easy fellow," made his appearance, delivered a short speech, made a low bow, and went out. Dixon, who had produced such amazing good nature with "Zip Coon," next addressed them—and they soon quietly dispersed.

Dixon the editor

In early 1835, Dixon moved toLowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, in the United States. Alongside Cambridge, It is one of two traditional seats of Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in 2020, it was the fifth most populous city in Massachusetts as of ...

, a small town growing out of the Industrial Revolution. By April, he had taken the epithet "The National Melodist" and was editing ''Dixon's Daily Review''. The paper took as motto "Knowledge—Liberty—Utility—Representation—Responsibility" and championed the Whig Party, Radical Republicanism

Radicalism (from French , "radical") or classical radicalism was a historical political movement representing the leftward flank of liberalism during the late 18th and early 19th centuries and a precursor to social liberalism, social democra ...

, and the working class. ''Dixon's Daily Review'' also explored morality

Morality () is the differentiation of intentions, decisions and actions between those that are distinguished as proper (right) and those that are improper (wrong). Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of cond ...

and women's place in the rapidly changing society of the urban North.

Dixon's criticism of his colleagues did not win him any friends, and in June, the ''Boston Post

''The Boston Post'' was a daily newspaper in New England for over a hundred years before it folded in 1956. The ''Post'' was founded in November 1831 by two prominent Boston, Massachusetts, Boston businessmen, Charles Gordon Greene, Charles G. Gr ...

'' reported that he had "flogged one of the editors of the ''Lowell Castigator

Lowell may refer to:

Places United States

* Lowell, Arkansas

* Lowell, California

* Lowell, Florida

* Lowell, Idaho

* Lowell, Indiana

* Lowell, Bartholomew County, Indiana

* Lowell, Maine

* Lowell, Massachusetts

** Lowell National Historical ...

'', and was hunting after the other." By the next month, Dixon had sold his paper, and the new publishers were eager to point out that Dixon no longer had anything to do with its production. By August, rumors were circulating that Dixon had started up another paper called the ''News Letter'' and was selling it in Lowell and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. If he did, no copies are known to have survived.

By February 1836, Dixon was touring again. He played many well-attended shows in Boston that month and did a play at the Tremont Theatre. His recent forays into publishing had soured his image in the popular press, however, and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' satirized his lower-class audience:

''Tremont Teatre.'' At this classical establishment, Mr Dixon, "the American Buffo singer," is at present the star. His ''third'' night is announced! Will some of the enlightened citizens of the emporium favor us with their opinion of his performance? Is his Zip Coon as thrilling as Mr Wood's "Still so gently o'er me stealing?"On 16 and April 30, Dixon played the Masonic Temple in Boston. There he included material to appeal to his lower-class audience, such as a popular tune that he had adapted with lyrics about the Boston Fire Department. Nevertheless, he also reached out to a richer, middle-class patronage. For example, he played alongside a classically trained pianist, and he billed the performance as a "concert", a word typically reserved for high-class, non-blackface entertainment. Dixon earned a third of the gross from this engagement: $23.50. He still owed money to the printer of ''Dixon's Daily Review'', so these earnings were put in trust for the conductor of the orchestra to pick up at a later date. Dixon and the printer grew impatient and presented a forged note to the trustee to collect early. Within a few days, Dixon was arrested and jailed in Boston. The press took the opportunity to castigate him again: "''George Washington Dixon'', now cormorant of Boston jail, and ex-publisher, ex-editor, ex-broker, ex-melodist, &c., is quite out of tune." The ''

Boston Courier

The ''Boston Courier'' was an American newspaper based in Boston, Massachusetts. It was founded on March 2, 1824, by Joseph T. Buckingham as a daily newspaper which supported protectionism. Buckingham served as editor until he sold out completely ...

'' called Dixon "the most miserable apology for a vocalist that ever bored the public ear."

At the trial, held in mid-June, character witnesses testified that Dixon was "a harmless, inoffensive man, but destitute of business capacity" and "in reply to the question whether Dixon was '' non compos mentis,'' I consider him as being on the frontier line—sometimes on one side, and sometimes on the other, just as the breeze of fortune happens to blow." In the end, he was found not guilty when the prosecution failed to satisfy that he had known the document to be a forgery. Dixon took the opportunity to give a speech to the public outside. He then returned to the stage, earning a considerable $527.50 in late July.

Dixon was still guilty in the eyes of the press, however, and his letters to clear his name only made things worse:

Mister Zip Coon is at his old tricks again. So far from possessing the ability to write a letter Miss Nancy-Coal-Black-Rose Dixon cannot begin to write ten consecutive words of the English language, and he must have encountered "the Schoolmaster abroad" in the Athenian city that teaches "penmanship in six lessons," and that lately too if he can sign his name.By the end of 1836, Dixon had moved to Boston and started a new paper, the ''Bostonian; or, Dixon's Saturday Night Express''. The paper focused on working-class issues, religious values, and opposition to

abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

. It followed the lead of the ''Daily Review'' in exposing allegedly immoral affairs of well known Bostonians. One story told of two personalities eloping. Other Boston papers called the story false, and the ''Boston Herald

The ''Boston Herald'' is an American daily newspaper whose primary market is Boston, Massachusetts, and its surrounding area. It was founded in 1846 and is one of the oldest daily newspapers in the United States. It has been awarded eight Pulit ...

'' labeled Dixon a "knave". Dixon fired back, depicting the paper's editor, Henry F. Harrington, as a monkey.

In early 1837, Dixon was again in legal trouble. Harrington accused Dixon of stealing half a ream of paper from the '' Morning Post'', the principal competition to Harrington's ''Herald''. The judge eventually dismissed the case, agreeing that the paper had been taken, but ruling that no proof pointed to Dixon as the one who had taken it. Dixon gave another post-trial speech, followed by a stage show on February 4.

Not ten days after the end of the Harrington case, Dixon was charged with forging a signature on a bail bond pertaining to his previous debt from July 1835. He was sent to Lowell and jailed. The press responded with its usual glee: "George has been a great eulogist, the defender of the Constitution! But he cannot defend himself." At his hearing on February 15, bail was set at $1000, an unheard of amount for the time. Unable to pay, he was transferred to a jail in Concord, Massachusetts

Concord () is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. At the 2020 census, the town population was 18,491. The United States Census Bureau considers Concord part of Greater Boston. The town center is near where the conflu ...

.

Dixon's March 16 trial ended in conviction. His appeal to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is the court of last resort, highest court in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Although the claim is disputed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, the SJC claims the di ...

on April 17 resulted in a hung jury, and his prosecutors dropped the charges against him. He gave another of his by now trademark post-trial addresses. The ''Boston Post'' wrote: "I begin to think that the Melodist bears a charmed life—and as was often said to be done in olden time, has made a bargain with the Being of Darkness for a certain term of years, during which he may defy the majesty of the law, and the wrath of his enemies."

Another stage tour followed, with concerts in Lowell, New England, and Maine. This was an apparent success, with one reviewer saying that Dixon had "a voice which ''all'' unite in pronouncing to be of remarkable richness and compass." That Fall, he may have contemplated a tour with James Salisbury, a black musician and dancer well known in lower-class districts of Boston such as Ann Street. Instead, he appeared on December 6 at the upper-class Opera Saloon, singing selections from popular operas. His fame (or notoriety) served to get him listed as a candidate for the Boston mayoral race in December. Dixon won nine votes, despite his polite refusal to serve should he be elected.

The ''Polyanthos''

Dixon performed in Boston through the end of February 1838. That spring, he moved to New York City, where he re-entered the publishing business with a newspaper called the ''Polyanthos and Fire Department Album''. Dixon again championed the lower class and aimed to expose the sordid affairs of the rich, especially those who preyed upon lower-class women. An early ''Polyanthos'' alleged that Thomas Hamblin, manager of the Bowery Theatre, was engaging in an affair with Miss Missouri, a teen-aged performer there. Within ten days of publication, Miss Missouri turned up dead, reportedly killed by "inflammation of the brain caused by the violent misconduct of Miss Missouri's mother and the publication of an abusive article in ''The Polyanthos''." On July 28, Hamblin accosted Dixon. Another assault in August prompted Dixon to start carrying a pistol. Undaunted, Dixon continued his attacks on Hamblin and others in the ''Polyanthos''. He exposed another alleged affair, this between a merchant named Rowland R. Minturn and the wife of a shipmaker named James H. Roome. Twelve days after the publication, Roome killed himself. Another article alleged thatFrancis L. Hawks

Francis Lister Hawks (June 10, 1798 – September 26, 1866) was an American writer, historian, educator and priest of the Episcopal Church. After practicing law with some distinction (and a brief stint as politician in North Carolina), Hawks bec ...

, an Episcopalian rector and reverend at the St. Thomas Church of New York, had been engaging in illicit sexual behavior. On December 31, Dixon was in court, charged with libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

. Dixon spent a week in jail, then paid the $2000 bail. However, before he could even leave the jailhouse, he was arrested for a charge leveled by Rowland Minturn's brothers that Dixon's article had resulted in the man's death.

Bail was raised to $9000, an enormous amount, which Dixon protested. The prosecution argued that "The accused is a ''criminal of the blackest dye'', and by his infamous publication is morally guilty of no less than three murders, and I hope the court will not diminish the amount of bail one iota!" It did not. Nevertheless, a notorious New York madam named Adeline Miller paid it, and Dixon walked free. Only a month later, though, she had sent Dixon back to jail for unknown reasons. Facing seven counts (four from Hawks and three from the Minturns), the singer and editor remained incarcerated for two months while he awaited trial.

The Minturn case came first, on April 15, 1839. After three days, the jury came back unable to reach a verdict, and the Minturn brothers dropped the charges. Dixon returned to jail, but Hawks dropped his charges from four to three. The judge lowered bail to $900 on April 20, and Dixon walked free.

The press renewed their attacks on him:

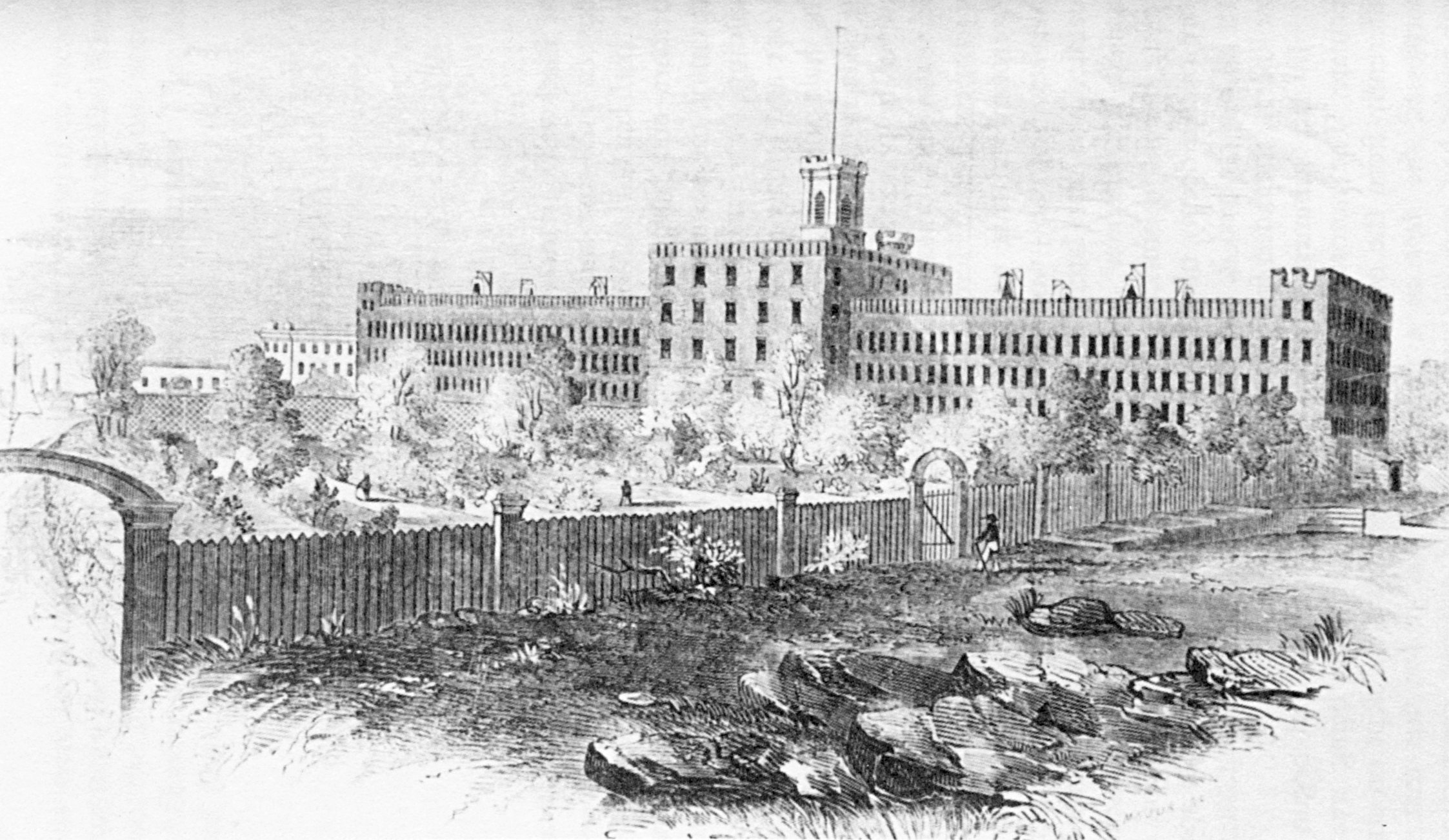

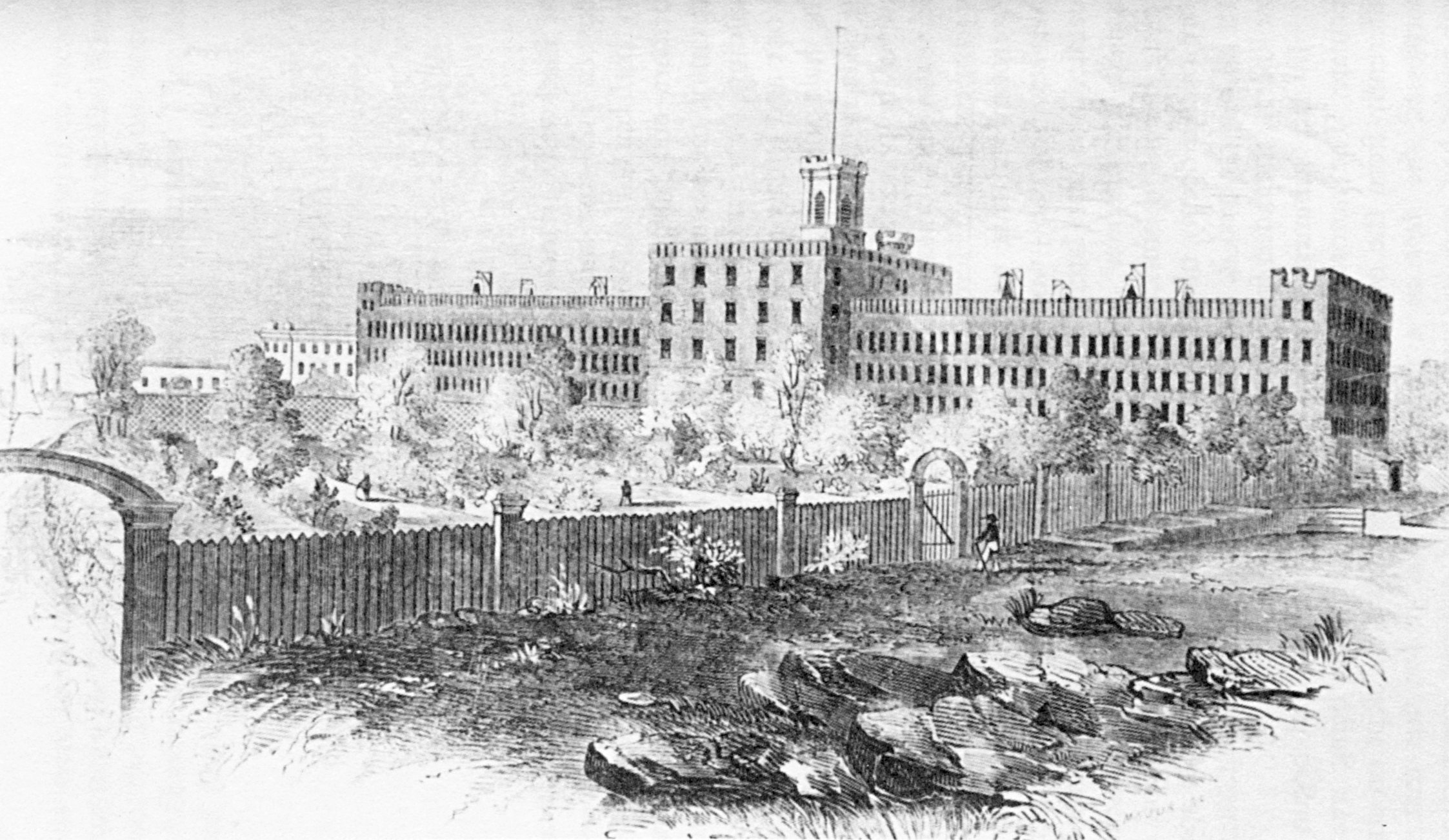

To those who know the true character, and something of the personal history of this imbecile vagrant, the exuberance of indignation with which he is pursued, appears truly ridiculous. That he is disgusting, a nuisance, and a bore, we know—and so is a spider. Nobody would dream, however, of extinguishing the latter insect with a park of artillery; though all the city seem to have fancied that George Washington Dixon could be conquered with no less. The truth of him is, that he is a most unmitigated fool; and as to his pursuing any person with malice, he is not capable of any sentiment requiring the appreciation of real or fancied injury. If he were kicked down stairs, he could not decide, until told by some one else, whether the kick was the result of accident or design, and if design, whether it was intended as a compliment or an insult.Dixon fought back in the ''Polyanthos'' by defending himself and his motives, and to some degree, he seems to have succeeded. The ''Herald'' for one admitted that his trial had exposed an unsavory facet of the upper class. Nevertheless, on May 10, Dixon changed his plea to guilty regarding one count, and the next day did the same for the other two. He was sentenced to six months of hard labor at the New York State Penitentiary at Blackwell's Island. Dixon reportedly responded, "This is a pretty situation for an editor." He would later claim that Hawks had paid him $1000 to change his plea.

The press reacted with its usual fervor:

The press reacted with its usual fervor:

Dixon is a mulatto, and was, not many years ago, employed in this city, in an oyster house to open oysters and empty the shells into the carts before they were carried away. He is an impudent scoundrel, aspires to every thing, and was fit to be any body's fool. Somebody used his name (such as he called himself, for negroes have, by right, no surnames) as the publisher of a newspaper, in which every body, almost, was libelled. He is now caged, and, we may hope, will, when he comes out of prison, go to opening oysters, or some other employment appropriate to his habits and color.Dixon served out his sentence then returned to New York. He resumed the ''Polyanthos'', emerging as the leader of a cadre of like-minded editors interested in exposing immorality.Cockrell, ''ANB'', 645. Dixon now focused his efforts on Austrian dancer Fanny Elssler, whom he accused of sexual misconduct. On August 21, 1840, he went so far as to rally a riot against her and then published the inciting speech in the ''Polyanthos''.Cockrell, ''Demons'', 128. He then targeted men who seduced young, working-class women, boarders who cheated their landlords, dysfunctional banks, and so-called British agents who were supposedly stirring up anti-American sentiment among American Indians and black slaves. Dixon claimed to be "a battering-ram against vice and folly in every shape", writing:

''The Polyanthos'' cannot die. The protecting Providence that watches over the safety of the just, and defeats the machinations of the wicked, will make it bloom ... We prophesy that the latest descendant of the youngest newsboy will animate his hearers with the desire to emulate the enviable fame of DIXON! Our name will be handed down to the end of time as one of the most independent men of the nineteenth century! Our ''very hat'' will become a relic.

On February 16, 1841, Dixon turned to a crusade against a New York

On February 16, 1841, Dixon turned to a crusade against a New York abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

ist known as Madame Restell

Ann Trow Lohman (May 6, 1812 – April 1, 1878), better known as Madame Restell, was a British-born American abortion provider who practiced in New York City.

Early life

Ann Trow was born in Painswick, Gloucestershire, England in 1812 to John a ...

. He vowed to reprint an anti-Restell editorial every week until the authorities took notice or Restell stopped running newspaper ads for her abortion services. As for abortion itself, Dixon claimed that it subverted marriage by inhibiting procreation and encouraged female infidelity.

Dixon kept his word, illustrating the editorial in later runs with woodcuts of Restell carrying a skull-and-crossbones emblem. When the March 17 '' New York Courier'' quoted the New York grand jury as saying "We earnestly pray that if there is no law that will reach this adame Restell Adame is both a surname and a given name. It may refer to:

Surname:

* Alfredo Adame (born 1958), Mexican actor

* Joe Adame (born 1945), American politician

* Marco Antonio Adame (born 1960), Mexican politician

Given name:

* Adame Ba Konaré

Ada ...

which we present as a ''public nuisance'', the court will take measures for procuring the passage of such a law", Dixon responded with the March 20 headline "Restell caught at last!" On March 22, Ann Lohman, part of the husband-and-wife team behind the Restell name, was arrested. Dixon claimed vindication and covered the trial over several issues of the ''Polyanthos''. After her conviction on July 20, he wrote, "the monster in human shape ... has ... been convicted of one of the most hellish acts ever perpetrated in a Christian land!"

On September 12, a man in the street struck Dixon in the head with an ax, which prompted some of the only positive press Dixon ever enjoyed that was not related to his singing. The ''Uncle Sam'' praised his editing and writing: "Go on martyr of virtue, go on and prosper! Go on getting out extras, and defending the sacredness of the marriage institution. Go on through malice, opposition, fiery trials, persecutions and assassinations—posterity will do thee justice ... !"

Even with positive press, Dixon's troubles with the courts were not over. Around September 16, he allegedly assaulted Peter D. Formal, who was taking down bills that Dixon had posted. Dixon failed to appear for his October court date, and he skipped later dates on 1 and November 11. On November 19, he again was placed under arrest for obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be use ...

as part of a citywide campaign by the district attorney to fight yellow journalism. On January 13, 1842, Dixon was indicted for the charges ''in absentia''. A warrant was issued for his arrest on April 13. By this time, he had handed the ''Polyanthos'' to Louse Leah, and the charges were eventually dropped.

In late 1841, Dixon had gotten into another row with a colleague. William Joseph Snelling obtained a warrant against him, and Dixon countersued. Snelling wrote anonymously in the ''Flash'':

We know him for a greedy, sordid, unscrupulous knave, of old; ... We are aware that men are judged by the company they keep and that we shall be blamed for having had anything to do with Dixon. Be it so.—We deserve rebuke, we have suffered for our folly and, if that is not enough, we are content to sit down in sackcloth and ashes; the meet attire of fools who trust to a person so vile that the English language cannot express his unmitigated baseness.In keeping with sexual morality at the time, Dixon and his colleagues sometimes checked bordellos for cleanliness, friendliness, and other factors. Snelling drew from this, linking Dixon to organized prostitution and alleging that he had connections to a madam named Julia Brown. Eventually, another editor named George B. Wooldridge joined with Dixon for a few issues of the ''True Flash'', but they did not sell well. Rumors circulated at this time that Dixon was to be married, but sources disagreed over the identity of the fiancée; one said she was a Congressman's daughter, another that she was a madam. The ''Flash'' published a story that Brown and a prostitute named Phoebe Doty had been seen fighting over the Melodist. If Dixon did marry, no record survives of it.

Later career

Beginning in 1842, Dixon took on a number of new occupations, including animal magnetist andspiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' i ...

specializing in clairvoyance. A fad for public competitions and feats of endurance served as another vehicle for him to keep his name in the public eye; he became a "pedestrian", a long-distance sport walker. The participation of Dixon, a blackface singer and dancer, in these contests presaged the challenge dances of performers such as Master Juba

Master Juba (ca. 1825 – ca. 1852 or 1853) was an African-American dancer active in the 1840s. He was one of the first black performers in the United States to play onstage for white audiences and the only one of the era to tour with a white mi ...

and John Diamond in the next few years.Knowles 77.

In February, he competed to win $4,000 by walking 48 hours without stopping. When the prize failed to materialize, Dixon charged admission to watch him. Later that month, Dixon tried to break this record by walking 50 hours. His publicity was, as usual, bad. ''Brother Jonathan

Brother Jonathan is the personification of New England. He was also used as an emblem of the U.S. in general, and can be an allegory of capitalism. His too-short pants, too-tight waistcoat and old-fashioned style reflect his taste for inexpensi ...

'' gave this advice: "walk in one direction all the time, from this part of the compass, till ocean fetches him up, and then see how far he can swim." He walked for 60 hours that summer in Richmond, then did in five hours and 35 minutes in Washington, D.C. Dixon tried many other feats of endurance. For example, in late August, he stood on a plank for three days and two nights with no sleep. In September, he paced for 76 hours on a 15-foot-long (five-meter) platform.

Meanwhile, he did not give up his singing career. In early 1843, Dixon (now called "Pedestrian and Melodist") appeared at least once more at the Bowery Theatre, and he played on bills with Richard Pelham

Richard Ward "Dick" Pelham (February 13, 1815 – October 1876), born Richard Ward Pell, was an American blackface performer. He was born in New York City.

Pelham regularly did blackface acts in the early 1840s both solo and as part of a duo or ...

and Billy Whitlock

William M. Whitlock (1813 – 1878) was an American blackface performer. He began his career in entertainment doing blackface banjo routines in circuses and dime shows, and by 1843 he was well known in New York City. He is best known for h ...

. On January 29, he performed at a benefit for Dan Emmett

Daniel Decatur Emmett (October 29, 1815June 28, 1904) was an American songwriter, entertainer, and founder of the first troupe of the blackface minstrel tradition, the Virginia Minstrels. He is most remembered as the composer of the song "Dixie ...

. These concerts would be his last.

Despite these excursions into athletics and entertainment, Dixon still considered himself an editor. He started a new paper called ''Dixon's Regulator'' by March, and he renewed his public crusade in New York. On February 22, 1846, he posted handbills around the city publicizing a meeting to protest further activities by Madame Restell. At the rally the next day, several hundred people listened to Dixon speak against the abortionist, calling for her neighbors to demand her eviction or else to take matters into their own hands. The crowd then walked to her residence three blocks away to shout threats but eventually dispersed. Restell responded with a letter to the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' and ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' alleging that Dixon was simply trying to extort money from her in return for an end to his agitation:

Again and again have I been applied to by his emissaries for money, and as often have they been refused; and, as a consequence, I have been vilified and abused without stint or measure, which, of course, I expected, and, of the two, would prefer to his praise.During the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, Dixon added some timely political references to "Zip Coon" and briefly returned to the public eye. Another crusade seems to have drawn Dixon away from New York in 1847. He was probably one of the first Radical Republicans to entrench himself as a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

in the Yucatán in a bid to annex more territory for the United States.

Dixon retired to New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, sometime before 1848. A city directory gives his address as "Literary Tent", and his obituary in the '' Baton Rouge Daily Gazette and Comet'' states that the Poydras Market "by night and day, was the home of this waif upon society ... The 'General' was not without friends who contributed an odd 'five' to him when too frail to move about."Obituary, March 23, 1861, ''Baton Rouge Daily Gazette and Comet''. Quoted in Cockrell, ''Demons'', 196 note 190. He came down with pulmonary Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

sometime in mid-1860. On February 27, 1861, he checked into the New Orleans Charity Hospital, noting his occupation as "editor". Dixon died on March 2.

Notes

References

* Browder, Clifford (1988). ''The Wickedest Woman in New York: Madame Restell, the Abortionist''. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books. * Cockrell, Dale (1997). ''Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World''. Cambridge University Press. * Cockrell, Dale (1999). "Dixon, George Washington". ''American National Biography'', Vol. 24 or 6. New York: Oxford University Press. * Knowles, Mark (2002). ''Tap Roots: The Early History of Tap Dancing''. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. * Toll, Robert C. (1974). ''Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-century America''. New York: Oxford University Press. * Watkins, Mel (1994). ''On the Real Side: Laughing, Lying, and Signifying—The Underground Tradition of African-American Humor that Transformed American Culture, from Slavery to Richard Pryor. New York: Simon & Schuster. * Wilmeth, Don B. and Bigsby, C. W. E., eds. (1998). ''The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Beginnings to 1870''. New York: Cambridge University Press. {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, George Washington 1801 births 1861 deaths 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American male singers American male dancers American male racewalkers American male stage actors Blackface minstrel performers 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis Tuberculosis deaths in Louisiana American mercenaries Musicians from Boston Musicians from Lowell, Massachusetts Musicians from New Orleans Musicians from Richmond, Virginia People from Roosevelt Island Ventriloquists American circus performers Male actors from New Orleans 19th-century American dancers Actors from Lowell, Massachusetts Male actors from Boston American male journalists 19th-century American male actors 19th-century American male writers Singers from Louisiana Journalists from Virginia Male actors from Richmond, Virginia