George Reid (Australian politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

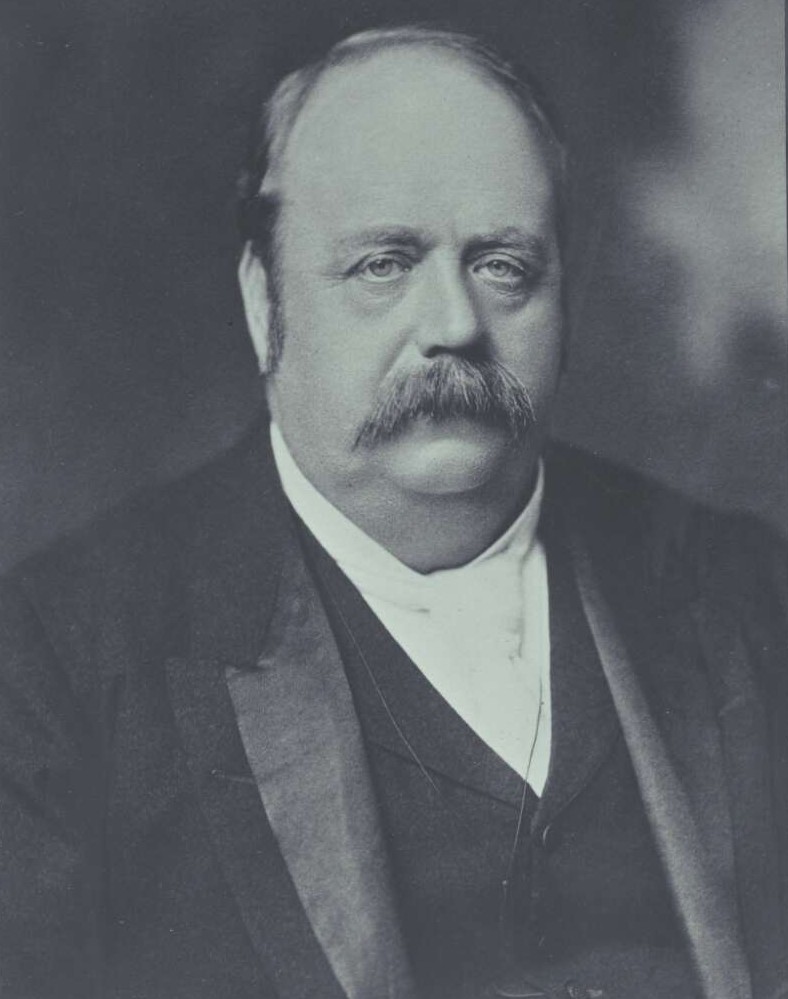

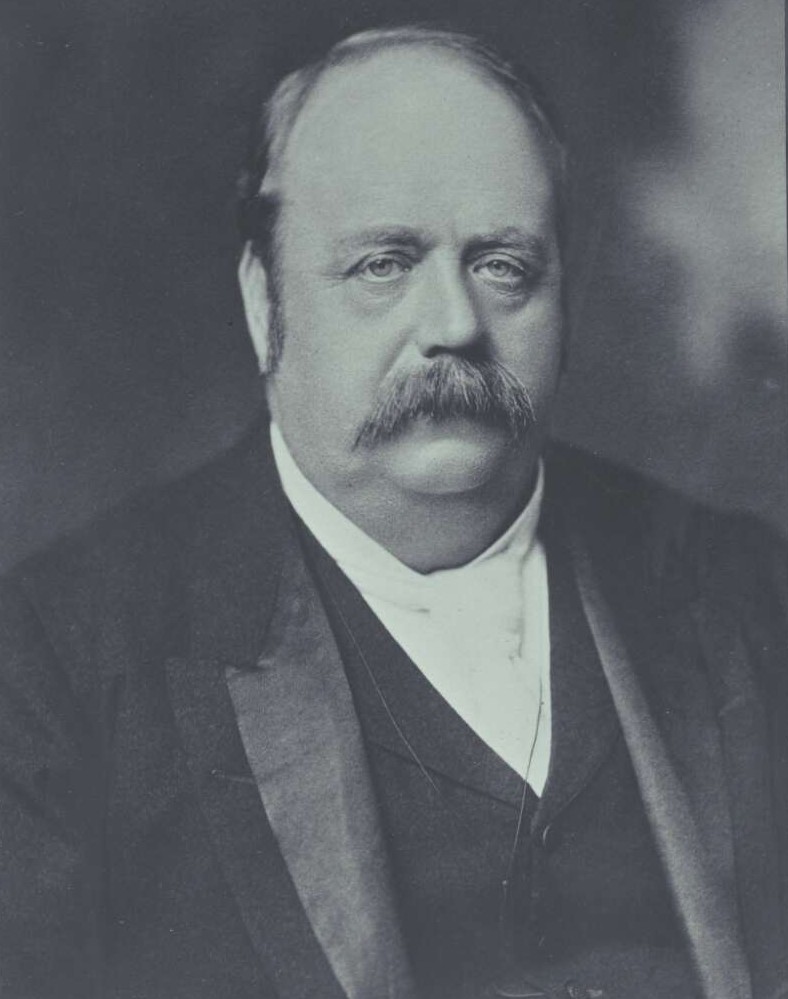

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth

In September

In September

Reid supported the federation of the Australian colonies, but since the campaign was led by his

Reid supported the federation of the Australian colonies, but since the campaign was led by his

In 1910, Reid was appointed as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

Reid was extremely popular in Britain, and in 1916, when his term as High Commissioner ended, he was elected unopposed to the

In 1910, Reid was appointed as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

Reid was extremely popular in Britain, and in 1916, when his term as High Commissioner ended, he was elected unopposed to the

In 1897 Reid was made an Honorary

In 1897 Reid was made an Honorary Stamp

/ref>

Archival records and sources

held at the National Archives of Australia

Audio lecture on the life of George Reid

– National Museum of Australia

Undated photo of George Reid and Mrs. Oliver T. Johnston

from Library of Congress collection , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Reid, George 1845 births 1918 deaths Prime Ministers of Australia Premiers of New South Wales Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian Leaders of the Opposition Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs Members of the Australian House of Representatives for East Sydney Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly Free Trade Party members of the Parliament of Australia UK MPs 1910–1918 Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian Presbyterians Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery People from Johnstone People educated at Scotch College, Melbourne Treasurers of New South Wales High Commissioners of Australia to the United Kingdom Attorneys General of the Colony of New South Wales Solicitors General for New South Wales Commonwealth Liberal Party members of the Parliament of Australia Scottish emigrants to Australia 20th-century Australian politicians Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Australian monarchists Australian King's Counsel

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament under the princip ...

from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislatur ...

from 1894 to 1899. He led the Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states, was an Australian political party, formally organised in 1887 in New South Wales, ...

from 1891 to 1908.

Reid was born in Johnstone

Johnstone ( sco, Johnstoun,

gd, Baile Iain) is a town ...

, gd, Baile Iain) is a town ...

Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Re ...

, Scotland. He and his family immigrated to Australia when he was young. They initially settled in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

, but moved to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

when Reid was 13, at which point he left school and began working as a clerk. He later joined the New South Wales civil service, and rose through the ranks to become secretary of the Attorney-General's Department. Reid was also something of a public intellectual, publishing several works in defence of liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

and free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

. He began studying law in 1876 and was admitted to the bar in 1879. In 1880, he resigned from the civil service to run for parliament, winning election to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament Ho ...

.

From 1883 to 1884, Reid served as Minister of Public Instruction in the government of Alexander Stuart Alexander Stuart may refer to:

* Alexander Stuart (scientist) (1673–1742), scientist, winner of the Copley Medal

*Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart (1807–1891), United States Secretary of the Interior between 1850 and 1853

*Alexander Stuart (Austral ...

. He joined the Free Trade Party of Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, (27 May 1815 – 27 April 1896) was a colonial Australian politician and longest non-consecutive Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, the present-day state of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia. He has ...

in 1887, but refused to serve in Parkes' governments due to personal enmity. When Parkes resigned as party leader in 1891, Reid was elected in his place. He became premier after the 1894 election and remained in office for just over five years. Despite never winning majority government

A majority government is a government by one or more governing parties that hold an absolute majority of seats in a legislature. This is as opposed to a minority government, where the largest party in a legislature only has a plurality of seats ...

, Reid was able to pass a number of domestic reforms concerning the civil service and public finances. He was an advocate of federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

and played a part in drafting the Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the A ...

, where he became known as a strong defender of his colony's interests. In 1901, he was elected to the new Federal Parliament representing the Division of East Sydney

The Division of East Sydney was an Australian Electoral Division in New South Wales. The division was created in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It was abolished in 1969. It was named ...

.

Reid retained the leadership of the Free Trade and Liberal Association after federation, and consequently became Australia's first Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

. For the first few years, the Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

governed with the support of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms t ...

. Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

's Protectionist minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in t ...

collapsed in April 1904, and he was briefly succeeded by Labor's Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia, in office from 27 April to 18 August 1904. He served as the inaugural federal lea ...

, who proved unable to govern and resigned after four months. As a result, Reid became prime minister in August 1904, heading yet another minority government. He included four Protectionists in his cabinet, but was unable to achieve much before his government was brought down in July 1905. One notable exception was the passage of the landmark Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904

The ''Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904'' (Cth) was an Act of the Parliament of Australia, which established the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, besides other things, and sought to introduce the rule of law i ...

, which dealt with industrial relations.

At the 1906 election, Reid secured the most votes in the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of ...

and the equal-most seats, but was well short of a majority and could not form government. He resigned as party leader in 1908, after opposing the formation of the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

(a merger with the Protectionists). Reid accepted an appointment as Australia's first High Commissioner to the United Kingdom

The following is the list of ambassadors and high commissioners to the United Kingdom, or more formally, to the Court of St James's. High commissioners represent member states of the Commonwealth of Nations and ambassadors represent other stat ...

in 1910, and remained in the position until 1916. He subsequently won election to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 ...

, serving until his sudden death two years later.

Early life

Reid was born on 25 February 1845 inJohnstone

Johnstone ( sco, Johnstoun,

gd, Baile Iain) is a town ...

, gd, Baile Iain) is a town ...

Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Re ...

, Scotland. He was the fifth of seven children born to Marion (née Crybbace) and John Reid; he had four older brothers and two younger sisters. He was named after George Houstoun, a former Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

MP for the Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Re ...

constituency who had died a few years earlier. Reid's father, the son of a farmer, was born in Tarbolton

Tarbolton ( sco, Tarbowton) is a village in South Ayrshire, Scotland. It is near Failford, Mauchline, Ayr, and Kilmarnock. The old Fail Monastery was nearby and Robert Burns connections are strong, including the Bachelors' Club museum.

Meanin ...

, Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of ...

. At the time of George's birth he was a minister in the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

, which he had joined in 1839 after previously ministering in various secessionist Presbyterian churches; he remained loyal to the established church in the Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

. In 1834, he had married the daughter of another minister, Edward Crybbace; she was about nine years his junior.

In April 1845, Reid and his family moved to Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, England, where his father had been appointed minister of an expatriate Presbyterian congregation. His two younger sisters were born there. The family struggled financially, and his father made the decision to emigrate to Australia. Reid arrived in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

in May 1852, and his father subsequently led congregations in Essendon Essendon may refer to:

Australia

*Electoral district of Essendon

*Electoral district of Essendon and Flemington

*Essendon, Victoria

**Essendon railway station

**Essendon Airport

*Essendon Football Club in the Australian Football League

United King ...

and North Melbourne

North Melbourne is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, north-west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Melbourne local government area. North Melbourne recorded a population of 14,953 at ...

. He moved the family to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

in 1858. Reid received his only formal schooling at the Melbourne Academy, now known as Scotch College. He received a classical education, and in later life recalled that he had "no appetite for that wide range of metaphysical propositions which juveniles were expected to comprehend"; he found Greek a "lazy horror". He left school aged about 13, when the family settled in Sydney, and began working as a junior clerk in a merchant's counting house

A counting house, or counting room, was traditionally an office in which the financial books of a business were kept. It was also the place that the business received appointments and correspondence relating to demands for payment.

As the use of ...

. At the age of 15 he joined the debating society at the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts

The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts (SMSA) is the longest running School of Arts (also known as a " Mechanics' Institute") and the oldest continuous lending library in Australia.

Founded in 1833, the school counted many of the colony's educat ...

, and according to his autobiography, "a more crude novice than he had never begun the practise of public speaking". In Sydney, Reid's father became a colleague of John Dunmore Lang

John Dunmore Lang (25 August 1799 – 8 August 1878) was a Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, historian, politician and activist. He was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian re ...

at the Scots Church, and then from 1862 until his death in 1867 was the minister of the Mariners' Church on George Street. His mother, who died in 1885, was involved in the ragged schools

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute childre ...

movement. In later life, Reid praised his parents for his good upbringing.

Public service career

In 1864, Reid joined the New South Wales Civil Service as an assistant accountant in the Colonial Treasury, with an annual salary of £200. He was promoted to clerk of correspondence and contracts in 1868, and then chief clerk of correspondence in 1874 on a salary of £400. In 1876 he began to study law seriously, which would provide the independent income necessary to pursue a parliamentary career (given that parliamentary service was unpaid at the time). He became head of the Attorney-General's Department in 1878. In 1879, Reid qualified as abarrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

. He made a name for himself by publishing pamphlets on topical issues. In 1875, he published his ''Five Essays on Free Trade'', which brought him an honorary membership of the Cobden Club

The Cobden Club was a society and publishing imprint, based in London, run along the lines of a gentlemen's club of the Victorian era, but without permanent club premises of its own. Founded in 1866 by Thomas Bayley Potter for believers in Free ...

, and in 1878 the government published his ''New South Wales, the Mother Colony of the Australians'', for distribution in Europe.

Political career

Reid's career was aided by his quick wit and entertaining oratory; he was described as being "perhaps the best platform speaker in the Empire", both amusing and informing his audiences "who flocked to his election meetings as to popular entertainment". In one particular incident his quick wit and affinity for humour were demonstrated when a heckler pointed to his ample paunch and exclaimed "What are you going to call it, George?" to which Reid replied: "If it's a boy, I'll call it after myself. If it's a girl I'll call it Victoria. But if, as I strongly suspect, it's nothing but piss and wind, I'll name it after you." His humour, however, was not universally appreciated.Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

detested Reid, describing him as "inordinately vain and resolutely selfish" and their cold relationship would affect both their later careers.

Reid was elected top of the poll to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament Ho ...

as a member for the four-member electoral district of East Sydney

East Sydney was an electoral district for the Legislative Assembly, in the Australian colony of New South Wales created in 1859 from part of the Electoral district of Sydney City, covering the eastern part of the current Sydney central busines ...

in the 1880 New South Wales colonial election

The 1880 New South Wales colonial election was held between 17 November and 2 December 1880. This election was for all of the 108 seats in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly and it was conducted in 43 single-member constituencies, 25 2-mem ...

. He was not very active at first, as he was building up his legal practice, although he was concerned to reform the Robertson Land Acts, which had not prevented 96 land holders from controlling eight million acres (32,000 km2) between them. Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, (27 May 1815 – 27 April 1896) was a colonial Australian politician and longest non-consecutive Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, the present-day state of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia. He has ...

and John Robertson attempted to make minor amendments to the land acts but were defeated and at the subsequent election Parkes' party lost many seats.

The new premier, Alexander Stuart Alexander Stuart may refer to:

* Alexander Stuart (scientist) (1673–1742), scientist, winner of the Copley Medal

*Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart (1807–1891), United States Secretary of the Interior between 1850 and 1853

*Alexander Stuart (Austral ...

, offered Reid the position of Colonial Treasurer in January 1883, but he thought it wiser to accept the junior office of Minister of Public Instruction. He served 14 months in this office and succeeded in passing a much improved Education Act, which included the establishment of the first government high schools in the leading towns, technical schools (which became a model for the other colonies) and the provision of evening lectures at the university.

In February 1884, Reid lost his seat in parliament owing to a technicality; The Elections and Qualifications Committee held that the Governor had already issued five proclamations prior to the appointment of Francis Suttor to the office of Minister of Public Instruction thus both Suttor and his successor Reid were incapable of being validly appointed. At the resulting by-election Reid was defeated by a small majority as a result of the government's financial hardships due to the loss of revenue from the suspension of land sales. In 1885

Events

January–March

* January 3– 4 – Sino-French War – Battle of Núi Bop: French troops under General Oscar de Négrier defeat a numerically superior Qing Chinese force, in northern Vietnam.

* January 4 &n ...

he was re-elected in East Sydney and took a great part in the free trade or protection issue. He supported Sir Henry Parkes on the free trade side but, when Parkes came into power in 1887, declined a seat in his ministry. Parkes offered him a portfolio two years later and Reid again refused. He did not like Parkes personally and felt he would be unable to work with him. When payment of members of parliament was passed, Reid, who had always opposed it, paid the amount of his salary into the treasury. Reid had become one of Sydney's leading barristers by impressing juries by his cross-examinations and was made a Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister o ...

in 1898. In May 1891 four free traders, Reid, Jack Want

John Henry "Jack" Want (4 May 1846 – 22 November 1905) was an Australian barrister and politician, as well as the 19th Attorney-General of New South Wales.

Early life

Want was born at the Glebe, Sydney, the fourth son of nine children of R ...

, John Haynes and Jonathan Seaver, voted against the Fifth Parkes ministry

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash that ...

in a motion of no confidence, which was only defeated by the casting vote of the Speaker of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The Speaker of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the presiding officer of the Legislative Assembly, New South Wales's lower chamber of Parliament. The current Speaker is Jonathan O'Dea, who was elected on 7 May 2019. Traditionally a ...

. Whilst the government survived the motion, parliament was dissolved on 6 June 1891.

Premier

In September

In September 1891

Events

January–March

* January 1

** Paying of old age pensions begins in Germany.

** A strike of 500 Hungarian steel workers occurs; 3,000 men are out of work as a consequence.

** Germany takes formal possession of its new Af ...

, the Parkes ministry was defeated, the Dibbs government succeeded it, and Parkes retired from the leadership of the Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states, was an Australian political party, formally organised in 1887 in New South Wales, ...

. Reid was elected leader of the opposition in his place. In 1891, he married Florence (Flora) Ann Brumby, who was 23 years old to his 46. He managed to form his party into a coherent group although it "ran the whole gamut from conservative Sydney merchants through middle-class intellectuals to reformers who wished to replace indirect by direct taxation for social reasons."

At the 1894 election Reid made the establishment of a real free trade tariff with a system of direct taxation the main item of his policy, and had a great victory. Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to b ...

and other well-known protectionists lost their seats, Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

was reduced from 30 to 18, and Reid formed his first cabinet

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

. One of his earliest measures was a new lands bill which provided for the division of pastoral leases into two-halves, one of which was to be open to the free selector, while the pastoral lessee got some security of tenure for the other half. Classification of crown lands according to their value was provided for, and the free selector, or his transferee, had to reside on the property.

At an early stage of the session, Parkes pressed the question of federation, and in response Reid invited the premiers of the other colonies to meet in conference on 29 January 1895. This resolved in favour of an elected Australasian Federal Convention, that would draw up a federal constitution, which would then to be subject of a referendum in each colony. Meanwhile, Reid had great trouble in passing his land and income tax bills. When he did get them through the Assembly the New South Wales Legislative Council

The New South Wales Legislative Council, often referred to as the upper house, is one of the two chambers of the parliament of the Australian state of New South Wales. The other is the Legislative Assembly. Both sit at Parliament House in t ...

threw them out. Reid obtained a dissolution, was victorious at the polls, and heavily defeated Parkes for the new single-member electoral district of Sydney-King

Sydney-King was an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales, created in 1894 in central Sydney from part of the electoral district of East Sydney and named after Governor King. It was initi ...

. He eventually succeeded in passing his acts, which were moderate, but was strenuously opposed by the council, and it was only the fear that the chamber might be swamped with new appointments that eventually wore down the opposition. Reid was also successful in bringing in reforms in the keeping of public accounts and in the civil service generally. Other acts dealt with the control of inland waters, and much needed legislation relating to public health, factories, and mining, was also passed. In five years he achieved more than any of his predecessors.

On four occasions between December 1895 and May 1899 Reid was temporarily appointed to the vacant position of Solicitor General for New South Wales

Solicitor General for New South Wales, known informally as the Solicitor General, is one of the Law Officers of the Crown, and the deputy of the Attorney General. They can exercise the powers of the Attorney General in the Attorney General's a ...

to allow him to deputise for the Attorney General of New South Wales

The Attorney General of New South Wales, in formal contexts also Attorney-General or Attorney General for New South Wales and usually known simply as the Attorney General, is a minister in the Government of New South Wales who has responsibili ...

, Jack Want

John Henry "Jack" Want (4 May 1846 – 22 November 1905) was an Australian barrister and politician, as well as the 19th Attorney-General of New South Wales.

Early life

Want was born at the Glebe, Sydney, the fourth son of nine children of R ...

, in his absence. (1988 Autumn) Bar News: Journal of the NSW Bar Association 22. Reid took on the position of Attorney-General in addition to being Premier in the last months of his government.

Federation

Reid supported the federation of the Australian colonies, but since the campaign was led by his

Reid supported the federation of the Australian colonies, but since the campaign was led by his Protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

opponent Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to b ...

he did not take a leading role. He was dissatisfied by the draft constitution, especially the power of a Senate, elected on the basis of States rather than population, to reject money bills.

Following the Adelaide session in 1897 of the National Australasian Convention, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

sent the Colonial Office's extensive and sometimes critical comments on the current draft of the federal constitution to Reid (then in London for Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

's Diamond Jubilee), for his "private & independent" consideration. At the Sydney and Melbourne sessions of the Convention in 1897 and 1898, Reid moved amendments based on those comments, covertly obtaining several concessions to British wishes. He denied a suggestion that he had been "talking with ‘Joe’". Reid did copy Chamberlain's comments to a select few other delegates, but they never revealed this. They included Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to b ...

, chair of the Drafting Committee, which accommodated some of Chamberlain's more technical points.

In the aftermath of the Convention, Reid made his famous "Yes-No" speech at Sydney Town Hall, on 28 March 1898. He told his audience that he intended to deal with the bill "with the deliberate impartiality of a judge addressing a jury". After speaking for an hour and three-quarters the audience was still uncertain about his verdict. He concluded by declaring "my duty to Australia demands me to record my vote in favour of the bill". Barton congratulated him on stage, but later he and other Federationists were frustrated by Reid saying that, while he felt he could not desert the cause, he would not recommend any course to the electors: "Now, I say to you, having pointed out my mind, and having shown you the dark places as well as the light places of this constitution, I hope every man in this country, without coercion from me, without any interference from me, will judge for himself." He consistently kept this attitude until the poll was taken on 3 June 1898. This earned him the nickname "Yes-No Reid". The referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

in New South Wales resulted in a small majority in favour, but the yes votes fell about 8000 short of the required 80,000. Subsequently, Reid was able to secure greater concessions for New South Wales.

At the general election held soon after, Barton challenged Reid in the premier's seat of Sydney-King. Although defeated him, but his party came back with a reduced majority. Reid fought for federation at the second referendum and it was carried in New South Wales, with 56.5 percent of valid votes cast for 'Yes'. "A bizarre combination of the Labor Party, protectionists, Federation enthusiasts and die-hard anti-Federation free traders" censured Reid for paying the expenses of John Neild who had been commissioned to report on old-age pensions, prior to parliamentary approval. Governor Beauchamp refused Reid a dissolution of parliament, and Reid was defeated in a no confidence motion, 75 to 41, in September 1899. By this time Reid had grown extremely overweight and sported a walrus moustache and a monocle, but his buffoonish image concealed a shrewd political brain.

Federal politics

Leader of the Opposition (1901–1904)

Reid was elected to the first federal Parliament as the Member for theDivision of East Sydney

The Division of East Sydney was an Australian Electoral Division in New South Wales. The division was created in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It was abolished in 1969. It was named ...

at the 1901 Australian federal election

The 1901 Australian federal election for the inaugural Parliament of Australia was held in Australia on Friday 29 March and Saturday 30 March 1901. The elections followed Federation and the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 Ja ...

. The Free Trade Party won 28 out of 75 seats in the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of ...

, and 17 out of 36 seats in the Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia. There are a t ...

. Labor no longer trusted Reid and gave their support to the Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to b ...

Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

government, so Reid became the first Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, a position well-suited to his robust debating style and rollicking sense of humour. In the long tariff debate Reid was at a disadvantage as parliament was sitting in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

and he could not entirely neglect his practice as a barrister in Sydney, as his parliamentary income was less than a tenth of his income from his legal practice. In their old stronghold of New South Wales free traders had won 12 seats, but Labor won six, and the old compact between Labor and Reid was a thing of the past.

On 18 August 1903, Reid resigned (the first member of the House of Representatives to do so) and challenged the government to oppose his re-election on the issue of its refusal to accept a system of equal electoral districts. On 4 September he successfully contested the 1903 East Sydney by-election

A by-election was held for the Australian House of Representatives electorate of East Sydney in New South Wales on 4 September 1903, a Friday. It was triggered by the resignation of George Reid on 18 August 1903. The writ for the by-election was i ...

against a Labor opponent. He was the only person in Australian federal parliamentary history to win back his seat at a by-election triggered by his own resignation, until John Alexander in 2017.

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

took over from Barton as Prime Minister and leader of the Protectionists. At the 1903 election, the Free Trade Party won 24 seats, with the Labor vote increasing mainly at the expense of the Protectionists.

Prime Minister (1904–1905)

In August 1904, when theWatson

Watson may refer to:

Companies

* Actavis, a pharmaceutical company formerly known as Watson Pharmaceuticals

* A.S. Watson Group, retail division of Hutchison Whampoa

* Thomas J. Watson Research Center, IBM research center

* Watson Systems, make ...

government resigned, Reid became Prime Minister. He was the first former state premier to become Prime Minister (the only other to date being Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

). Reid did not have a majority in either House, and he knew it would be only a matter of time before the Protectionists patched up their differences with Labor, so he enjoyed himself in office while he could. In July 1905 the other two parties duly voted him out, and he left office with good grace.

Leader of the Opposition (1905–1908)

Reid adopted a strategy of trying to reorient the party system alongLabor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

vs. non-Labor lines – prior to the 1906 election, he renamed his Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states, was an Australian political party, formally organised in 1887 in New South Wales, ...

to the Anti-Socialist Party. Reid envisaged a spectrum running from socialist to anti-socialist, with the Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

in the middle. This attempt struck a chord with politicians who were steeped in the Westminster tradition and regarded a two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually refe ...

as very much the norm. Zachary Gorman has argued that this attempt to impose clear 'lines of cleavage' in Federal politics was inspired by Reid's friend Joseph Carruthers who had achieved a political realignment in New South Wales that destroyed the Progressive middle party and created a Liberal-Labor divide. For Reid, anti-socialism was a natural product of his long-standing belief in Gladstonian liberalism.

Reid referred to Labor publicly using a damaging visual negative image of Labor as a hungry socialist tiger that would devour all. The anti-socialist campaign led to the Protectionist vote and seat count dropping significantly at the 1906 election, while both Reid's party and Labor won 26 seats each. The Deakin government continued with Labor support for the time being, despite only holding 16 seats after losing 10, although with another 5 independent Protectionists. Reid's anti-socialist campaign had nevertheless laid the groundwork for the desired realignment, and liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

would come to sit on the centre-right

Centre-right politics lean to the right of the political spectrum, but are closer to the centre. From the 1780s to the 1880s, there was a shift in the Western world of social class structure and the economy, moving away from the nobility and ...

of Australian politics.

In 1907–08, Reid strenuously resisted Deakin's commitment to increase tariff rates. When Deakin proposed the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

, a "Fusion" of the two non-Labor parties, Reid resigned as party leader on 16 November 1908. The following day, Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook, (7 December 1860 – 30 July 1947) was an Australian politician who served as the sixth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1913 to 1914. He was the leader of the Liberal Party from 1913 to 1917, after earlier servin ...

was made leader until the parties merged.

On 24 December 1909 Reid resigned from Parliament (he was the first Member to have resigned twice), however his seat was left vacant until the 1910 election. His seat of East Sydney was won by Labor's John West, in an election which saw Labor win 42 of 75 seats, against the CLP on 31 seats. Labor also won a majority in the Senate.

Later life and legacy

In 1910, Reid was appointed as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

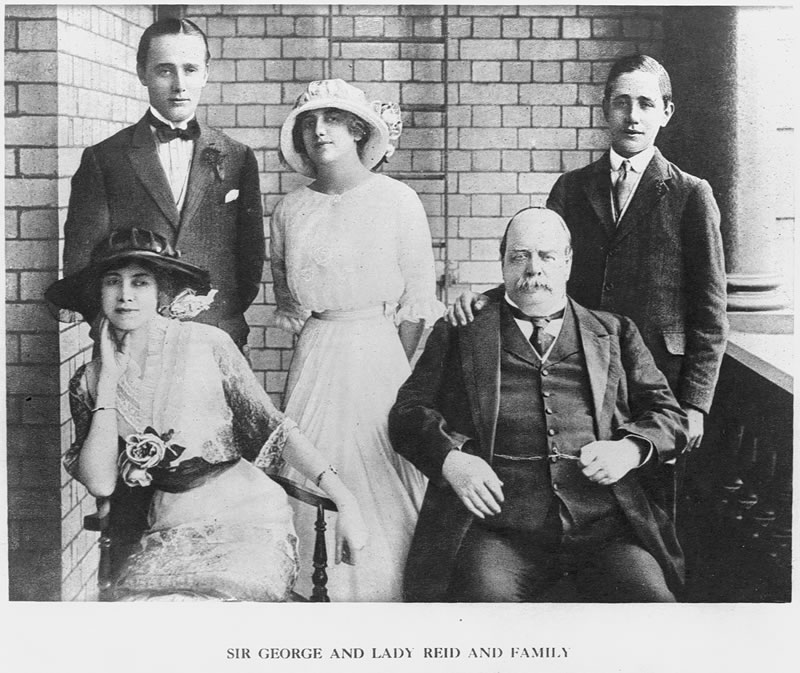

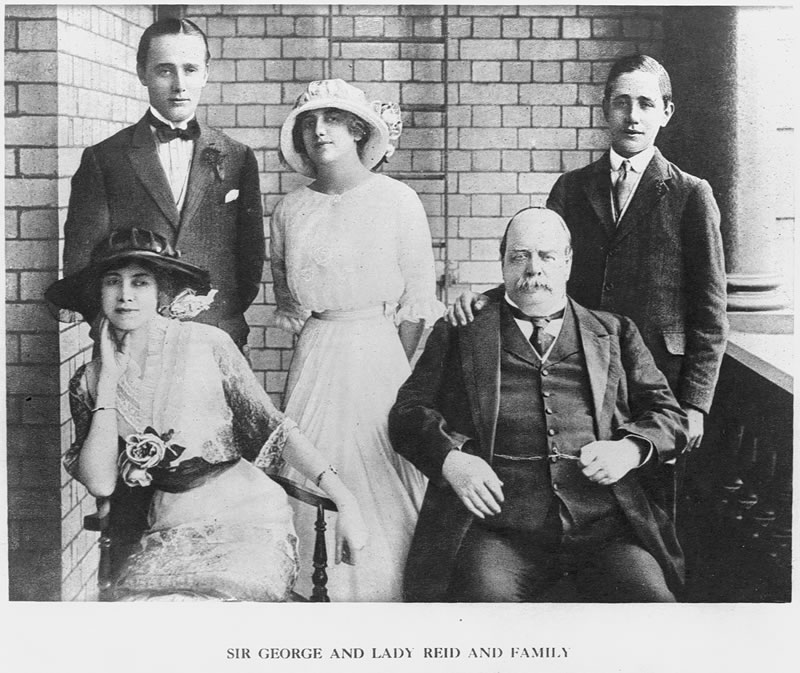

Reid was extremely popular in Britain, and in 1916, when his term as High Commissioner ended, he was elected unopposed to the

In 1910, Reid was appointed as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

Reid was extremely popular in Britain, and in 1916, when his term as High Commissioner ended, he was elected unopposed to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 ...

for the seat of St George, Hanover Square as a Unionist candidate, where he acted as a spokesman for the self-governing Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s in supporting the war effort. He died suddenly in London on 12 September 1918, aged 73, of cerebral thrombosis

A thrombus (plural thrombi), colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of cr ...

, survived by his wife and their two sons and daughter. His wife had become Dame Flora Reid

Dame Florence Ann "Flora" Reid, (née Brumby; 10 November 1867 – 1 September 1950) was the wife of Sir George Reid, the fourth Prime Minister of Australia.

Early life

Reid was born in Longford, Tasmania, the daughter of a farmer from t ...

GBE in 1917. He is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery

Putney Vale Cemetery and Crematorium in southwest London is located in Putney Vale, surrounded by Putney Heath and Wimbledon Common and Richmond Park. It is located within of parkland. The cemetery was opened in 1891 and the crematorium in 1938 ...

.

Reid's posthumous reputation suffered from the general acceptance of protectionist policies by other parties, as well as from his buffoonish public image. In 1989 W. G. McMinn published ''George Reid'', a serious biography designed to rescue Reid from his reputation as a clownish reactionary and attempt to show his Free Trade policies as having been vindicated by history.

Honours

In 1897 Reid was made an Honorary

In 1897 Reid was made an Honorary Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; la, Legis Civilis Doctor or Juris Civilis Doctor) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher ...

(DCL) by Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. Reid was also appointed a member of Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of e ...

(1904), a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(1911) and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

(1916).

In 1969 he was honoured on a postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the f ...

bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post, formally the Australian Postal Corporation, is the government business enterprise that provides postal services in Australia. The head office of Australia Post is located in Bourke Street, Melbourne, which also serves as a post ...

./ref>

Works

* '' The Australian Commonwealth and her relation to the British Empire'' (address, 1912)See also

* Reid MinistryNotes

References

Further reading

*External links

Archival records and sources

held at the National Archives of Australia

Audio lecture on the life of George Reid

– National Museum of Australia

Undated photo of George Reid and Mrs. Oliver T. Johnston

from Library of Congress collection , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Reid, George 1845 births 1918 deaths Prime Ministers of Australia Premiers of New South Wales Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian Leaders of the Opposition Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs Members of the Australian House of Representatives for East Sydney Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly Free Trade Party members of the Parliament of Australia UK MPs 1910–1918 Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian Presbyterians Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery People from Johnstone People educated at Scotch College, Melbourne Treasurers of New South Wales High Commissioners of Australia to the United Kingdom Attorneys General of the Colony of New South Wales Solicitors General for New South Wales Commonwealth Liberal Party members of the Parliament of Australia Scottish emigrants to Australia 20th-century Australian politicians Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Australian monarchists Australian King's Counsel