George MacDonald on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

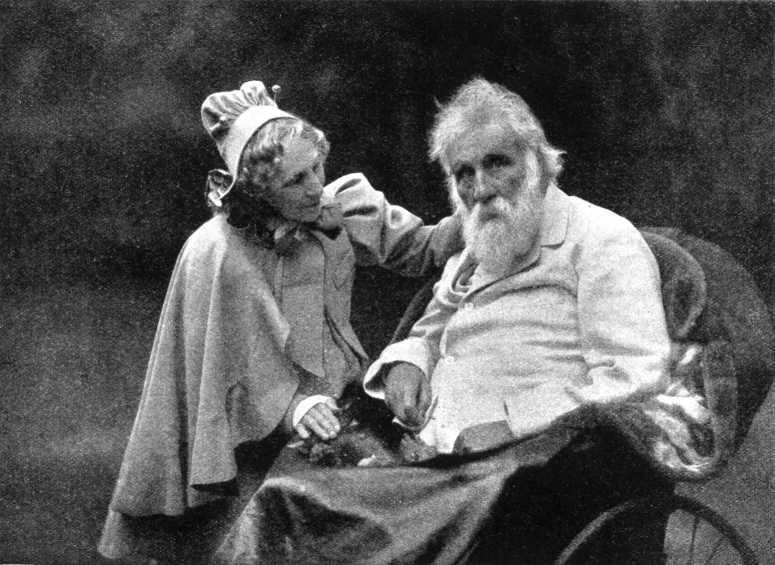

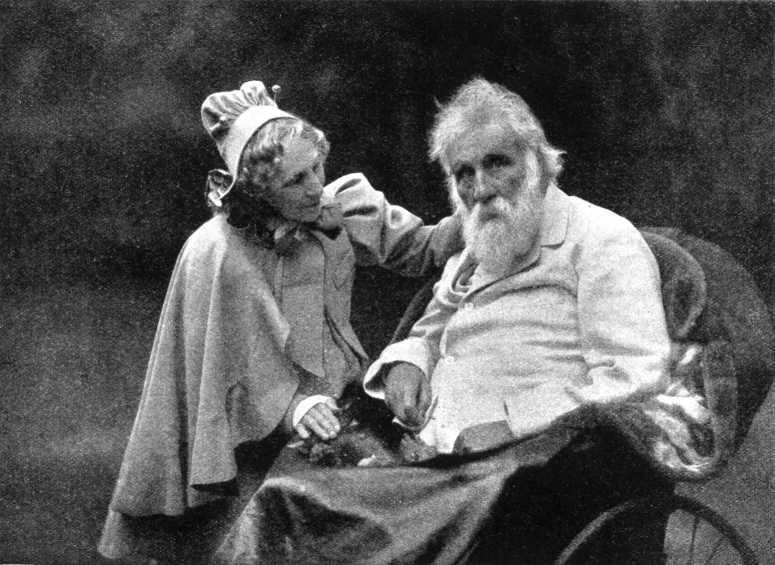

George MacDonald (10 December 1824 – 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet and Christian

MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, "I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children." MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, "When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?" He replied, "No. As much as they were will come upon them, possibly far more. ... The wrath will consume what they ''call'' themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear."

However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald's optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see

MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, "I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children." MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, "When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?" He replied, "No. As much as they were will come upon them, possibly far more. ... The wrath will consume what they ''call'' themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear."

However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald's optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see

Vol. 2

an

Vol. 3

each of ''ca.'' 300 pages. Also issued by Lippincott in America in a single volume set in two columns in smaller font, in 210 pages, The entirety of the original text is available with a Broad Scots glossary by its digitizer, John Bechard, see Republished in edited form as Also as ''The Baronet's Song''. *''Paul Faber, Surgeon'' (1879; republished in edited form as ''The Lady's Confession''), a sequel to ''Thomas Wingfold, Curate'' *'' Mary Marston'' (1881; republished in edited form as ''A Daughter's Devotion'' and ''The Shopkeeper's Daughter'') *''Warlock o' Glenwarlock'' (1881; republished in edited form as ''Castle Warlock'' and ''The Laird's Inheritance'') *''Weighed and Wanting'' (1882; republished in edited form as ''A Gentlewoman's Choice'') *'' Donal Grant'' (1883; republished in edited form as ''The Shepherd's Castle''), a sequel to ''Sir Gibbie'' *''What's Mine's Mine'' (1886; republished in edited form as ''The Highlander's Last Song'') *''Home Again: A Tale'' (1887; republished in edited form as ''The Poet's Homecoming'') *'' The Elect Lady'' (1888; republished in edited form as ''The Landlady's Master'') *''A Rough Shaking'' (1891; republished in edited form as ''The Wanderings of Clare Skymer'') *''There and Back'' (1891; republished in edited form as ''The Baron's Apprenticeship''), a sequel to ''Thomas Wingfold, Curate'' and ''Paul Faber, Surgeon'' *''The Flight of the Shadow'' (1891) *''Heather and Snow'' (1893) :* :* ::* (republished in edited form in 1988) * ''Salted with fire'' :* ::* (republished in edited form in 1988) *''Far Above Rubies'' (1898)

''North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies''

St. Norbert College. Wisconsin. * * * * * * * * * * * *

Christian Classics Ethereal Library

containing a few poems and translations of Novalis (Cornell University'

a

(pdf format)

Alec Forbes of Howglen

(Ebook/PDF format) Physical collections

The Marion E. Wade Center

– George MacDonald research collection at Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL * George MacDonald Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Audio collections *

Audio recordings of GM Works ongoing

Free audio recording of "The Golden Key"

a

librivox.org

Biographical information

The George MacDonald Informational Web

on The Victorian Web

Scholarly work

''Wingfold''. A journal of George MacDonald. Published by Barbara Amell

The Works of George Macdonald

Website related to Wingfold.

The Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis and Friends – Taylor University at taylor.edu

Other links

* ttp://www.george-macdonald.com/ George MacDonald Society

Mark Twain and George MacDonald: The Salty and the Sweet

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Macdonald, George 1824 births 1905 deaths 19th-century Christian mystics 19th-century Christian universalists 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish poets 19th-century Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Aberdeen Christian novelists Christian poets Christian universalist clergy Christian universalist theologians Scottish fabulists Kailyard school Lallans poets Mythopoeic writers People from Huntly Protestant mystics Protestant philosophers Scottish anti-communists Scottish children's writers Scottish Christian theologians Scottish Christian universalists Scottish Congregationalist ministers Scottish Christian poets Scottish expatriates in Italy Scottish fantasy writers Scottish male novelists Scottish male poets 19th-century Scottish philosophers 20th-century Scottish philosophers Victorian novelists Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Congregational

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christianity, Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice Congregationalist polity, congregational ...

minister. He became a pioneering figure in the field of modern fantasy literature

Fantasy literature is literature set in an imaginary universe, often but not always without any locations, events, or people from the real world. Magic, the supernatural and magical creatures are common in many of these imaginary worlds. Fan ...

and the mentor of fellow-writer Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet, mathematician, photographer and reluctant Anglicanism, Anglican deacon. His most notable works are ''Alice ...

. In addition to his fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, household tale, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful bei ...

s, MacDonald wrote several works of Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

, including several collections of sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present context ...

s.

Early life

George MacDonald was born on 10 December 1824 inHuntly

Huntly ( or ''Hunndaidh'') is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, formerly known as Milton of Strathbogie or simply Strathbogie. It had a population of 4,460 in 2004 and is the site of Huntly Castle. Its neighbouring settlements include Keith ...

, Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire (; ) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the Shires of Scotland, historic county of Aberdeenshire (historic), Aberdeenshire, which had substantial ...

, Scotland, to George MacDonald, manufacturer, and Helen MacKay. His father, a farmer, was descended from the Clan MacDonald of Glen Coe and a direct descendant of one of the families that suffered in the massacre of 1692.

MacDonald grew up in an unusually literate environment: one of his maternal uncles, Mackintosh MacKay, was a notable Celtic scholar, editor of the ''Gaelic Highland Dictionary'' and collector of fairy tales and Celtic oral poetry. His paternal grandfather had supported the publication of an edition of James Macpherson's ''Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora (poem), Temora'' (1763), and later c ...

'', the controversial epic poem based on the Fenian Cycle

The Fenian Cycle (), Fianna Cycle or Finn Cycle () is a body of early Irish literature focusing on the exploits of the mythical hero Fionn mac Cumhaill, Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill and his Kóryos, warrior band the Fianna. Sometimes called the ...

of Celtic Mythology

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples.Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) ''The Ancient Celts''. Oxford, Oxford University Press , pp. 183 (religion), 202, 204–8. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed ...

and which contributed to the starting of European Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

. MacDonald's step-uncle was a Shakespeare scholar, and his paternal cousin another Celtic academic. Both his parents were readers, his father harbouring predilections for Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

, William Cowper

William Cowper ( ; – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter.

One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the Engli ...

, Chalmers, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

, and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, to quote a few, while his mother had received a classical education which included multiple languages.

An account cited how the young George suffered lapses in health in his early years and was subject to problems with his lungs such as asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

, bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

and even a bout of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. This last illness was considered a family disease and two of MacDonald's brothers, his mother, and later three of his own children died from the illness. Even in his adult life, he was constantly traveling in search of purer air for his lungs.

MacDonald grew up in the Congregational Church

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

, with an atmosphere of Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

. However, his family was atypical, with his paternal grandfather a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

-born, fiddle-playing, Presbyterian elder; his paternal grandmother an Independent church rebel; his mother was a sister to the Gaelic-speaking radical who became moderator of the Free Church, while his step-mother, to whom he was also very close, was the daughter of a priest of the Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church (; ) is a Christian denomination in Scotland. Scotland's third largest church, the Scottish Episcopal Church has 303 local congregations. It is also an Ecclesiastical province#Anglican Communion, ecclesiastical provi ...

.

MacDonald graduated from the King's College, Aberdeen

King's College in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, the full title of which is The University and King's College of Aberdeen (''Collegium Regium Aberdonense''), is a formerly independent university founded in 1495 and now an integral part of the Univer ...

in 1845 with a degree in chemistry and physics. He spent the next several years struggling with matters of faith and deciding what to do with his life. His son, biographer Greville MacDonald, stated that his father could have pursued a career in the medical field but he speculated that lack of money put an end to this prospect. It was only in 1848 that MacDonald began theological training at Highbury College for the Congregational ministry.

Early career

MacDonald was appointed minister of Trinity Congregational Church,Arundel

Arundel ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Arun District of the South Downs, West Sussex, England.

The much-conserved town has a medieval castle and Roman Catholic cathedral. Arundel has a museum and comes second behind much la ...

, in 1850, after briefly serving as a locum minister in Ireland. However, his sermons—which preached God's universal love and that everyone was capable of redemption—met with little favour and his stipend

A stipend is a regular fixed sum of money paid for services or to defray expenses, such as for scholarship, internship, or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from an income or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work pe ...

was cut in half. In May 1853, MacDonald tendered his resignation from his pastoral duties at Arundel. Later he was engaged in ministerial work in Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, leaving that because of poor health. An account cited the role of Lady Byron in convincing MacDonald to travel to Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

in 1856 with the hope that the sojourn would help turn his health around. When he got back, he settled in London and taught for some time at the University of London. MacDonald was also for a time editor of ''Good Words for the Young''.

Writing career

MacDonald's first realistic novel '' David Elginbrod'' was published in 1863. MacDonald is often regarded as the founding father of modern fantasy writing. His best-known works are '' Phantastes'' (1858), '' The Princess and the Goblin'' (1872), '' At the Back of the North Wind'' (1868–1871), and ''Lilith

Lilith (; ), also spelled Lilit, Lilitu, or Lilis, is a feminine figure in Mesopotamian and Jewish mythology, theorized to be the first wife of Adam and a primordial she-demon. Lilith is cited as having been "banished" from the Garden of Eden ...

'' (1895), all fantasy novels, and fairy tales

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, household tale, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the Folklore, folklore genre. Such stories typically feature Magic (supernatural), magic, Incantation, e ...

such as " The Light Princess", " The Golden Key", and " The Wise Woman". MacDonald claimed that "I write, not for children, but for the child-like, whether they be of five, or fifty, or seventy-five." MacDonald also published some volumes of sermons, the pulpit not having proved an unreservedly successful venue.

After his literary success, MacDonald went on to do a lecture tour in the United States in 1872–1873, after being invited to do so by a lecture company, the Boston Lyceum Bureau. On the tour, MacDonald lectured about other poets such as Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

, Shakespeare, and Tom Hood. He performed this lecture to great acclaim, speaking in Boston to crowds in the neighbourhood of three thousand people.

MacDonald served as a mentor to Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet, mathematician, photographer and reluctant Anglicanism, Anglican deacon. His most notable works are ''Alice ...

; it was MacDonald's advice, and the enthusiastic reception of ''Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

'' by MacDonald's many sons and daughters, that convinced Carroll to submit ''Alice'' for publication.Reis, Richard H. (1972). ''George MacDonald'', pp. 25–34. Twayne Publishers, Inc. Carroll, one of the finest Victorian photographers, also created photographic portraits of several of the MacDonald children. MacDonald was also friends with John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

and served as a go-between in Ruskin's long courtship with Rose La Touche. While in America he was befriended by Longfellow and Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

.

MacDonald's use of fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction that involves supernatural or Magic (supernatural), magical elements, often including Fictional universe, imaginary places and Legendary creature, creatures.

The genre's roots lie in oral traditions, ...

as a literary medium for exploring the human condition greatly influenced a generation of notable authors, including C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

, who featured him as a character in his '' The Great Divorce''. In his introduction to his MacDonald anthology, Lewis speaks highly of MacDonald's views:

Others he influenced include J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

and Madeleine L'Engle. MacDonald's non-fantasy novels, such as ''Alec Forbes'', had their influence as well; they were among the first realistic Scottish novels, and as such MacDonald has been credited with founding the "kailyard school

The Kailyard school is a proposed literary movement of Scottish literature, Scottish fiction; kailyard works were published and were most popular roughly from 1880–1914. The term originated from literary critics who mostly disparaged the works s ...

" of Scottish writing.

Chesterton cited '' The Princess and the Goblin'' as a book that had "made a difference to my whole existence, ... in showing "how near both the best and the worst things are to us from the first ... and making all the ordinary staircases and doors and windows into magical things."

Later life

In 1877 he was given acivil list

A civil list is a list of individuals to whom money is paid by the government, typically for service to the state or as honorary pensions. It is a term especially associated with the United Kingdom, and its former colonies and dominions. It was ori ...

(monastic poverty/civil duty) pension. From 1879 he and his family lived in Bordighera

Bordighera (; , locally ) is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Imperia, Liguria (Italy).

Geography

Bordighera is located from the land border between Italy and France, the French coast is visible from the town. Having the Capo Sant'Ampel ...

, in a place much loved by British expatriates, the Riviera dei Fiori in Liguria

Liguria (; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is roughly coextensive with ...

, Italy, almost on the French border. In that locality there also was an Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

church, All Saints, which he attended. Deeply enamoured of the Riviera, he spent 20 years there, writing almost half of his whole literary production, especially the fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction that involves supernatural or Magic (supernatural), magical elements, often including Fictional universe, imaginary places and Legendary creature, creatures.

The genre's roots lie in oral traditions, ...

work. MacDonald founded a literary studio in that Ligurian town, naming it '' Casa Coraggio'' (Bravery House). It soon became one of the most renowned cultural centres of that period, well attended by British and Italian travellers, and by locals, with presentations of classic plays and readings of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

and Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

often being held.

In 1900 he moved into St George's Wood, Haslemere

The town of Haslemere () and the villages of Shottermill and Grayswood are in south-west Surrey, England, around south-west of London. Together with the settlements of Hindhead and Beacon Hill (Hindhead, Surrey), Beacon Hill, they comprise ...

, a house designed for him by his son, Robert, its building overseen by his eldest son, Greville.

George MacDonald died on 18 September 1905 in Ashtead

Ashtead is a village in the Mole Valley district of Surrey, England, approximately south of central London. Ashtead is on the single-carriageway A24 road (Great Britain), A24 between Epsom and Leatherhead. The village is on the northern sl ...

, Surrey, England. He was cremated in Woking

Woking ( ) is a town and borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in north-west Surrey, England, around from central London. It appears in Domesday Book as ''Wochinges'', and its name probably derives from that of a Anglo-Saxon settleme ...

, Surrey, and his ashes were buried in Bordighera

Bordighera (; , locally ) is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Imperia, Liguria (Italy).

Geography

Bordighera is located from the land border between Italy and France, the French coast is visible from the town. Having the Capo Sant'Ampel ...

, in the English cemetery, along with his wife Louisa and daughters Lilia and Grace.

Personal life

MacDonald married Louisa Powell in Hackney in 1851, with whom he raised a family of eleven children: Lilia Scott (1852–1891), Mary Josephine (1853–1878), Caroline Grace (1854–1884), Greville Matheson (1856–1944), Irene (1857–1939), Winifred Louise (1858–1946), Ronald (1860–1933), Robert Falconer (1862–1913), Maurice (1864–1879), Bernard Powell (1865–1928), and George Mackay (1867–1909). His son Greville became a noted medical specialist, a pioneer of the Peasant Arts movement, wrote numerous fairy tales for children, and ensured that new editions of his father's works were published. Another son, Ronald, became a novelist. His daughter Mary was engaged to the artist Edward Robert Hughes until her death in 1878. Ronald's son, Philip MacDonald (George MacDonald's grandson), became a Hollywood screenwriter. Tuberculosis caused the death of several family members, including Lilia, Mary Josephine, Grace, and Maurice, as well as one granddaughter and a daughter-in-law. MacDonald was said to have been particularly affected by the death of Lilia, his eldest. There is a blue plaque on his home at 20 Albert Street, Camden, London.Theology

According to biographer William Raeper, MacDonald's theology "celebrated the rediscovery of God as Father, and sought to encourage an intuitive response to God and Christ through quickening his readers' spirits in their reading of the Bible and their perception of nature." MacDonald's oft-mentioneduniversalism

Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept within Christianity that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is se ...

is not the idea that everyone will automatically be saved, but is closer to Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( or Γρηγόριος Νυσσηνός; c. 335 – c. 394), was an early Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Nyssa from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 394. He is ve ...

in the view that all will ultimately repent and be restored to God.

MacDonald appears to have never felt comfortable with some aspects of Calvinist doctrine, feeling that its principles were inherently "unfair"; when the doctrine of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby Go ...

was first explained to him, he burst into tears (although assured that he was one of the elect). Later novels, such as ''Robert Falconer'' and ''Lilith

Lilith (; ), also spelled Lilit, Lilitu, or Lilis, is a feminine figure in Mesopotamian and Jewish mythology, theorized to be the first wife of Adam and a primordial she-demon. Lilith is cited as having been "banished" from the Garden of Eden ...

'', show a distaste for the idea that God's electing love is limited to some and denied to others.

Chesterton noted that only a man who had "escaped" Calvinism could say that God is easy to please and hard to satisfy.

MacDonald rejected the doctrine of penal substitution

Penal substitution, also called penal substitutionary atonement and especially in older writings forensic theory,Vincent Taylor (theologian), Vincent Taylor, ''The Cross of Christ'' (London: Macmillan & Co, 1956), pp. 71–72: '...the ''four main ...

ary atonement as developed by John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

, which argues that Christ has taken the place of sinners and is punished by the wrath of God in their place, believing that in turn it raised serious questions about the character and nature of God. Instead, he taught that Christ had come to save people from their sins, and not from a Divine penalty for their sins: the problem was not the need to appease a wrathful God, but the disease of cosmic evil itself. MacDonald frequently described the atonement

Atonement, atoning, or making amends is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some othe ...

in terms similar to the Christus Victor theory. MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, "Did he not foil and slay evil by letting all the waves and billows of its horrid sea break upon him, go over him, and die without rebound—spend their rage, fall defeated, and cease? Verily, he made atonement!"

MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, "I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children." MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, "When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?" He replied, "No. As much as they were will come upon them, possibly far more. ... The wrath will consume what they ''call'' themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear."

However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald's optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see

MacDonald was convinced that God does not punish except to amend, and that the sole end of His greatest anger is the amelioration of the guilty. As the doctor uses fire and steel in certain deep-seated diseases, so God may use hell-fire if necessary to heal the hardened sinner. MacDonald declared, "I believe that no hell will be lacking which would help the just mercy of God to redeem his children." MacDonald posed the rhetorical question, "When we say that God is Love, do we teach men that their fear of Him is groundless?" He replied, "No. As much as they were will come upon them, possibly far more. ... The wrath will consume what they ''call'' themselves; so that the selves God made shall appear."

However, true repentance, in the sense of freely chosen moral growth, is essential to this process, and, in MacDonald's optimistic view, inevitable for all beings (see universal reconciliation

Christian universalism is a school of Christian theology focused around the doctrine of universal reconciliation – the view that all human beings will ultimately be saved and restored to a right relationship with God. "Christian universalism" ...

).

MacDonald states his theological views most distinctly in the sermon "Justice", found in the third volume of ''Unspoken Sermons''.

Catalogue

The following is an incomplete list of MacDonald's published works in the genre now referred to as fantasy:Fantasy

* * * * , containing " The Golden Key", " The Light Princess", "The Shadows", and other short stories * *''Works of Fancy and Imagination'' (1871) The complete works of MacDonald collected in 10 volumes: ::* ::* ::* ::* ::* ::* ::* ::* ::* ::* * * (Published also as "The Lost Princess: A Double Story"; or as "A Double Story".) * Multiple versions with different content of ''The Light Princess and other Stories'' *''The Gifts of the Child Christ and Other Tales'' (1882; republished as ''Stephen Archer and Other Tales'') 1908 edition by Edwin Dalton, London was illustrated by Cyrus Cuneo and G. H. Evison. ::* ::* *'' The Day Boy and the Night Girl'' (1882) * , a sequel to ''The Princess and the Goblin'' *Fiction

*'' David Elginbrod'' (1863; republished in edited form as ''The Tutor's First Love''), originally published in three volumes *''Adela Cathcart'' (1864); contains many fantasy stories told by the characters within the larger story, including " The Light Princess", "The Shadows

The Shadows (originally known as the Drifters between 1958 and 1959) were an English instrumental rock group, who dominated the British popular music charts in the pre-Beatles era from the late 1950s to the early 1960s. They served as the bac ...

".

*'' Alec Forbes of Howglen'' (1865; edited by Michael Phillips and republished as ''The Maiden's Bequest;'' edited to children's version by Michael Phillips and republished as ''Alec Forbes and His Friend Annie'')

*''Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood'' (1867)

*''Guild Court: A London Story'' (1868; republished in edited form as ''The Prodigal Apprentice''). 1908 edition by Edwin Dalton, London was illustrated by G. H. Evison. Available online at Hathi Trust

HathiTrust Digital Library is a large-scale collaborative repository of digital content from research libraries. Its holdings include content digitized via Google Books and the Internet Archive digitization initiatives, as well as content digit ...

.

*''Robert Falconer'' (1868; republished in edited form as ''The Musician's Quest'')

*''The Seaboard Parish'' (1869), a sequel to ''Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood''

*'' Ranald Bannerman's Boyhood'' (republished in edited form as ''The Boyhood of Ranald Bannerman'') (1871)

*

*''The Vicar's Daughter'' (1871), a sequel to ''Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood'' and ''The Seaboard Parish''. 1908 edition by Sampson Low and Company, London was illustrated by Cyrus Cuneo and G. H. Evison.

*''The History of Gutta Percha Willie, the Working Genius'' (1873; republished in edited form as ''The Genius of Willie MacMichael''), usually called simply ''Gutta Percha Willie''

*''Malcolm'' (1875; republished in edited form by Michael Phillips as ''The Fisherman's Lady''))

*''St. George and St. Michael'' (1876; edited by Dan Hamilton and republished as ''The Last Castle'')

*''Thomas Wingfold, Curate'' (1876; republished in edited form as ''The Curate's Awakening'')

*'' The Marquis of Lossie'' (1877; republished in edited form as ''The Marquis' Secret''), the second book of ''Malcolm''

* Sir Gibbie (1879): With simultaneous publication oVol. 2

an

Vol. 3

each of ''ca.'' 300 pages. Also issued by Lippincott in America in a single volume set in two columns in smaller font, in 210 pages, The entirety of the original text is available with a Broad Scots glossary by its digitizer, John Bechard, see Republished in edited form as Also as ''The Baronet's Song''. *''Paul Faber, Surgeon'' (1879; republished in edited form as ''The Lady's Confession''), a sequel to ''Thomas Wingfold, Curate'' *'' Mary Marston'' (1881; republished in edited form as ''A Daughter's Devotion'' and ''The Shopkeeper's Daughter'') *''Warlock o' Glenwarlock'' (1881; republished in edited form as ''Castle Warlock'' and ''The Laird's Inheritance'') *''Weighed and Wanting'' (1882; republished in edited form as ''A Gentlewoman's Choice'') *'' Donal Grant'' (1883; republished in edited form as ''The Shepherd's Castle''), a sequel to ''Sir Gibbie'' *''What's Mine's Mine'' (1886; republished in edited form as ''The Highlander's Last Song'') *''Home Again: A Tale'' (1887; republished in edited form as ''The Poet's Homecoming'') *'' The Elect Lady'' (1888; republished in edited form as ''The Landlady's Master'') *''A Rough Shaking'' (1891; republished in edited form as ''The Wanderings of Clare Skymer'') *''There and Back'' (1891; republished in edited form as ''The Baron's Apprenticeship''), a sequel to ''Thomas Wingfold, Curate'' and ''Paul Faber, Surgeon'' *''The Flight of the Shadow'' (1891) *''Heather and Snow'' (1893) :* :* ::* (republished in edited form in 1988) * ''Salted with fire'' :* ::* (republished in edited form in 1988) *''Far Above Rubies'' (1898)

Poetry

The following is a list of MacDonald's published poetic works: *''Twelve of the Spiritual Songs of Novalis'' (1851), privately printed translation of the poetry ofNovalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (; ), was a German nobility, German aristocrat and polymath, who was a poet, novelist, philosopher and Mysticism, mystic. He is regarded as an inf ...

*

*

*

*

*

*

::* Volume I:''Within and Without'' pp 1-219

::* Volume II:''The Hiden Life and Other Poems'' pp 221-509

* Original privately printed

*, oclc=4118583, ref=none privately printed, with Greville Matheson and John Hill MacDonald

*

*''The Poetical Works of George MacDonald, 2 Volumes'' (1893)

*

*

Nonfiction

The following is a list of MacDonald's published works of non-fiction: *''Unspoken Sermons'' (1867) *''England's Antiphon'' (1868, 1874) *''The Miracles of Our Lord'' (1870) *''Cheerful Words from the Writing of George MacDonald'' (1880), compiled by E. E. Brown *''Orts: Chiefly Papers on the Imagination, and on Shakespeare'' (1882) *"Preface" (1884) to '' Letters from Hell'' (1866) by Valdemar Adolph Thisted *''The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: A Study With the Text of the Folio of 1623'' (1885) *''Unspoken Sermons, Second Series'' (1885) *''Unspoken Sermons, Third Series'' (1889) *''A Cabinet of Gems, Cut and Polished by Sir Philip Sidney; Now, for the More Radiance, Presented Without Their Setting by George MacDonald'' (1891) *''The Hope of the Gospel'' (1892) *''A Dish of Orts'' (1893) *''Beautiful Thoughts from George MacDonald'' (1894), compiled by Elizabeth DougallSee also

* Christian existentialism *Fairytale fantasy

Fairytale fantasy is a subgenre of fantasy. It is distinguished from other subgenres of fantasy by the works' heavy use of motifs, and often plots, from fairy tales or folklore.

History

Literary fairy tales were not unknown in the Roman era ...

* Mythopoeia

Mythopoeia (, ), or mythopoesis, is a subgenre of speculative fiction, and a theme in modern literature and film, where an artificial or fictionalized mythology is created by the writer of prose fiction, prose, poetry, or other literary forms. T ...

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *''North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies''

St. Norbert College. Wisconsin. * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

Digital collections * * *Christian Classics Ethereal Library

containing a few poems and translations of Novalis (Cornell University'

a

(pdf format)

Alec Forbes of Howglen

(Ebook/PDF format) Physical collections

The Marion E. Wade Center

– George MacDonald research collection at Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL * George MacDonald Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Audio collections *

Audio recordings of GM Works ongoing

Free audio recording of "The Golden Key"

a

librivox.org

Biographical information

The George MacDonald Informational Web

on The Victorian Web

Scholarly work

''Wingfold''. A journal of George MacDonald. Published by Barbara Amell

The Works of George Macdonald

Website related to Wingfold.

The Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis and Friends – Taylor University at taylor.edu

Other links

* ttp://www.george-macdonald.com/ George MacDonald Society

Mark Twain and George MacDonald: The Salty and the Sweet

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Macdonald, George 1824 births 1905 deaths 19th-century Christian mystics 19th-century Christian universalists 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish poets 19th-century Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Aberdeen Christian novelists Christian poets Christian universalist clergy Christian universalist theologians Scottish fabulists Kailyard school Lallans poets Mythopoeic writers People from Huntly Protestant mystics Protestant philosophers Scottish anti-communists Scottish children's writers Scottish Christian theologians Scottish Christian universalists Scottish Congregationalist ministers Scottish Christian poets Scottish expatriates in Italy Scottish fantasy writers Scottish male novelists Scottish male poets 19th-century Scottish philosophers 20th-century Scottish philosophers Victorian novelists Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland