George M. Stratton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Malcolm Stratton (September 26, 1865 – October 8, 1957) was an American psychologist who pioneered the study of perception in vision by wearing special glasses which inverted images up and down and left and right. He studied under one of the founders of modern psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, and started one of the first experimental psychology labs in America, at the

George Stratton was born on September 26, 1865 to

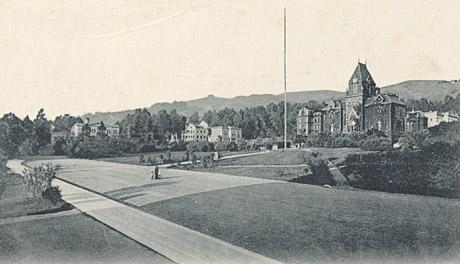

George Stratton was born on September 26, 1865 to  Stratton's early education was at the Oakland public schools and undergraduate education at the University of California. At the university he was a member of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity. He was also the editor of the student news publication, ''The Berkeleyan,'' in 1886. Stratton graduated in 1888 with an A.B. degree from the University of California, in a total graduating class of 34 students. He learned Latin and English and taught in Buenaventura High School in 1888–89, and was its principal in 1889–90. At the school he met and courted San Francisco-born Alice Elenore Miller.

Stratton then obtained an A.M. degree from Yale in 1890. He was a fellow in the philosophy department at Berkeley from 1891 to 1893. The chair of the philosophy department,

Stratton's early education was at the Oakland public schools and undergraduate education at the University of California. At the university he was a member of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity. He was also the editor of the student news publication, ''The Berkeleyan,'' in 1886. Stratton graduated in 1888 with an A.B. degree from the University of California, in a total graduating class of 34 students. He learned Latin and English and taught in Buenaventura High School in 1888–89, and was its principal in 1889–90. At the school he met and courted San Francisco-born Alice Elenore Miller.

Stratton then obtained an A.M. degree from Yale in 1890. He was a fellow in the philosophy department at Berkeley from 1891 to 1893. The chair of the philosophy department,

Returning to America in 1896, Stratton rejoined the University of California as an instructor. In 1897 he was promoted to

Returning to America in 1896, Stratton rejoined the University of California as an instructor. In 1897 he was promoted to

During World War I, Stratton served in army aviation developing psychological recruitment tests for aviators. He worked at San Francisco,

During World War I, Stratton served in army aviation developing psychological recruitment tests for aviators. He worked at San Francisco,

Open Library: George Stratton books free online

Social Psychology of International Conduct

Full text of PhD thesis (German)

Ancestry.com records

Daughter-in-law's obituaryA grandson's business life

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stratton, George M. American social psychologists Psychologists of religion Emotion psychologists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences University of California, Berkeley alumni Yale University alumni Leipzig University alumni University of California, Berkeley faculty Johns Hopkins University faculty Yale Divinity School faculty United States Army officers People from Oakland, California People from Berkeley, California People from Baltimore 1865 births 1957 deaths Presidents of the American Psychological Association Vision scientists Military personnel from California

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

. Stratton's studies on binocular vision

In biology, binocular vision is a type of vision in which an animal has two eyes capable of facing the same direction to perceive a single three-dimensional image of its surroundings. Binocular vision does not typically refer to vision where an ...

inspired many later studies on the subject. He was one of the initial members of the philosophy department at Berkeley, and the first chair of its psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between ...

department. He also worked on sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation an ...

, focusing on international relations and peace. Stratton presided over the American Psychological Association

The American Psychological Association (APA) is the largest scientific and professional organization of psychologists in the United States, with over 133,000 members, including scientists, educators, clinicians, consultants, and students. It ha ...

in 1908, and was a member of the National Academy of Sciences. He wrote a book on experimental psychology and its methods and scope; published articles on the studies at his labs on perception, and on reviews of studies in the field; served on several psychological committees during and after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

; and served as advisor to doctoral students who would go on to head psychology departments.

Stratton was born and brought up in the Oakland area of California, in a family with deep roots in America, and spent much of his career at Berkeley. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of California, an M.A. from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, and a PhD from the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

. He returned to the philosophy department at Berkeley, teaching psychology, and was promoted to associate professor. Stratton left for Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

in the early 1900s and spent a few years as faculty at the psychology department before returning to Berkeley. During this period, he focused on studies on sensation

Sensation (psychology) refers to the processing of the senses by the sensory system.

Sensation or sensations may also refer to:

In arts and entertainment In literature

* Sensation (fiction), a fiction writing mode

* Sensation novel, a Britis ...

and perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system ...

and the psychological effects of inverting sensory stimuli in different ways. He was involved in establishing some of the early regional associations devoted to the field of psychology.

Stratton served in the Army during World War I, developing psychological tests to select airmen for Army aviation. Exposure to the war effort prompted his interest in international relations and causes of wars. He was an anti-war believer who held psychology should aim to assist humanity's quest to avert future wars. He was optimistic that people and ethnicities, making up nations, could be taught to live in peace, though the races were not equal in inborn mental capacity, a belief he held as scientific. In the later part of his career he wrote books looking at international relations, war, and the differences between races on emotion

Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is currently no scientific ...

s. He was also a scholar of the classics and translated Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

.

Of Stratton's many contributions, his studies on perception and visual illusions

Within visual perception, an optical illusion (also called a visual illusion) is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; the ...

would continue to influence the field of psychology well after his death. Of the nine books he wrote, the first was a scholarly look at the methodology and scope of experimental psychology. The remaining, including one unfinished at his death, were on sociology, international relations and the issues of war and how findings from psychology could be used to eradicate conflict between nations. Stratton considered these issues more salient to the application of psychology in the real world, though his ideas on this front did not produce a lasting impact in the field because of their subjective and non-experimental nature.

Early life and education

George Stratton was born on September 26, 1865 to

George Stratton was born on September 26, 1865 to James Thompson Stratton

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, originally from Ossining, New York, and Cornelia A. Smith. His parents had met and married in New York in 1854, and settled back in Clinton, now East Oakland, California. James Stratton had been to California once before during the gold rush of 1850, sailing around North America and crossing by land the Panama stretch, but finding little gold. The senior Stratton traced his ancestry to the early settlers of the British settlements of America, and Cornelia Smith had Dutch and English forebears. James Stratton would live the rest of his life in California, pursuing a civil engineering career as County Surveyor for Alameda County

Alameda County ( ) is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,682,353, making it the 7th-most populous county in the state and 21st most populous nationally. The county seat is Oakland. Alam ...

in 1858–59 and later as the U.S. Surveyor-General of the state, and finally as Chief Deputy State Surveyor. An expert on the big Mexican land grants, he split up several of the Spanish deeds. One of his sons, Frederick, went to the University of California, today's Berkeley, and became a lawyer, state senator, and Collector of the Port of San Francisco

The Port of San Francisco is a semi-independent organization that oversees the port facilities at San Francisco, California, United States. It is run by a five-member commission, appointed by the Mayor and approved by the Board of Supervisors. Th ...

, before killing himself on November 30, 1915. Another, Robert Thomas, became a doctor in Oakland and died after a long illness on May 6, 1924. The couple also had a daughter, Jeanne, the later Mrs. Walter Good. George was their youngest child who lived past toddlerhood.

George Holmes Howison

George Holmes Howison (29 November 1834 – 31 December 1916) was an American philosopher who established the philosophy department at the University of California, Berkeley and held the position there of Mills Professor of Intellectual and Moral ...

, whom he met as an undergraduate, would become a significant influence on his life. He taught two philosophy courses, both with Howison. On March 14, 1893 he was appointed an instructor in the department of philosophy. As an instructor, he began teaching psychology and logic courses, in addition to a philosophy course.

Howison obtained a fellowship from the University of California for his protege to study at the University of Leipzig. On May 17, 1894, Stratton married Alice Miller at the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

in Berkeley, while being an instructor in the philosophy department. Immediately after, the couple left for the East on their way to Europe, with Stratton taking a leave of absence from Berkeley. He then spent two years at Wundt's Institute for Experimental Psychology at Leipzig, from where he received an M.A. and a PhD in 1896. He received his degree summa cum laude, with a thesis submitted to Wundt's publication, '' Philosophische Studien''.

Work years

Stratton spent his working years primarily at Berkeley. He founded the department of psychology at the university. He left once for Johns Hopkins and once to join the Army during World War I, serving in San Francisco, San Diego and New York.Early Berkeley

assistant professor

Assistant Professor is an academic rank just below the rank of an associate professor used in universities or colleges, mainly in the United States and Canada.

Overview

This position is generally taken after earning a doctoral degree

A docto ...

. By 1898 he no longer taught philosophy but several psychology courses. Two years later, he would influence the Philosophical Union into dedicating a year to investigating contemporary psychology. He himself presented a well-attended lecture series at the Union, with lively debates at the end, on psychological experiments. Over this time he also published three papers on his study with inverting lenses and how people adapt over time to such a view of the world: "Upright vision and the retinal image", "Vision without inversion of the retinal image", and "A mirror pseudoscope and the limit of visible depth", all in '' Psychological Review''. He also presented a report of experiments with inverted vision to the Science Association of the university.

Stratton also became a member of the APA. One of Stratton's psychology students in the Philosophy department was Knight Dunlap, a later chair at Johns Hopkins and University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California S ...

. Stratton became a director of the newly established psychology lab, in the philosophy department, in 1899. By 1900 he was an associate professor in the philosophy department, then headed by Howison. He contributed a paper to the Festschrift

In academia, a ''Festschrift'' (; plural, ''Festschriften'' ) is a book honoring a respected person, especially an academic, and presented during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the h ...

honoring Wundt's seventieth birthday in 1902: "Eye movements and the aesthetics of the visual form". He also taught a series of twenty lectures on philosophy and psychology at the Pacific Theological Seminary in Berkeley. His first daughter, Elenore, was born in 1900, and son James Malcolm around 1903.

Johns Hopkins and return to Berkeley

Stratton left Berkeley at end of June, 1904, and moved east to Johns Hopkins University as a professor of experimental psychology in October. At this time, philosophers and psychologists at Baltimore formed the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology (SSFY) and Stratton was one of the first 36 charter members. At its first meeting, he presented results of an experiment on fidelity of the senses. While Stratton was at Johns Hopkins, theSan Francisco Earthquake of 1906

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity sha ...

struck destroying large swaths of the city. He had specific suggestions on how to rebuild the city to resist earthquakes and fires even with the water supply cut off. He urged the city be split into districts with avenues or boulevards as firebreaks between the divisions.

Stratton's second daughter, Florence, was born in Baltimore on May 24, 1907. He left Johns Hopkins in October 1909, and was replaced there as professor of experimental psychology by John Broadus Watson.

The army

Rockwell Field

Rockwell Field is a former United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) military airfield, located northwest of the city of Coronado, California, on the northern part of the Coronado Peninsula across the bay from San Diego, California.

This airfield ...

, San Diego, and at Hazelhurst Field

Roosevelt Field is a former airport, located east-southeast of Mineola, Long Island, New York. Originally called the Hempstead Plains Aerodrome, or sometimes Hempstead Plains field or the Garden City Aerodrome, it was a training field (Hazel ...

, Mineola, New York. Joining as a captain, he was promoted to major in 1918 along with a transfer to Mineola. Stratton presided over the Army Aviation Examining Board in San Francisco in 1917, chaired the subcommittee of the National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

of the APA: "Psychological Problems of Aviation, including Examination of Aviation Recruits" in the summer of 1917, and headed the psychological section of the Medical Research Lab of the Army Medical Research Board at Hazelhurst Field

Roosevelt Field is a former airport, located east-southeast of Mineola, Long Island, New York. Originally called the Hempstead Plains Aerodrome, or sometimes Hempstead Plains field or the Garden City Aerodrome, it was a training field (Hazel ...

, a wing of the Army's Sanitary Corps, in 1918. As a member of the psychological division, his research focused on developing psychological recruiting tests for would-be aviators. The tests he designed tested for reaction times, ability to imagine completions of curves presented visually, and the ability to sense a gradual tilting of one's own body. Edward L. Thorndike pooled Stratton's results with other studies to statistically analyze and correlate weak performance to a poor flying record. Part of this research was carried out in the spring of 1918 with Captain Henmon at Kelly Field, and the army thought enough of the results to allow the tests for checking recruits in four new units.

Berkeley again

After the war, Stratton returned to Berkeley in January 1919. Stratton also taught at Berkeley's extension school, lecturing on "Psychology and health" in San Francisco to people from the medical profession in 1918–19, and in Oakland in 1919–20. By this time the introductory course on psychology was so in demand among the students, it was split into two, with Stratton and Warner Brown teaching it concurrently. His wife was the editor of the ''Semicentenary of the University of California'', a volume issued by the University Press at Berkeley in 1920. In 1921 his daughter, Elenore Stratton, graduated from Berkeley. That August she married Harvard graduate Edward Russell Dewey of New York at her father's house, and moved to the city, where she had done social settlement work following graduation. The same year his son attended Berkeley. The Berkeley department of psychology officially split from the department of philosophy, with Stratton as its first chair, on July 1, 1922. His second daughter, Florence, graduated from Berkeley with a B.A. in 1929.Retirement and death

Stratton retired in 1935, but remained at the university, and died on October 8, 1957 at the age of 92, a year after his wife's death. He kept coming to the university until just before the end. When he died he was working on a book, ''The Divisive and Unifying Forces of the Community of Nations'' though his eyesight was by then poor. During his retirement, he had lectured at universities across America, Europe and Asia. He was survived by his son, Malcolm Stratton, a physician at Berkeley; two daughters: Elenore, divorced and then married to Robert Fliess of New York, and Florence, married to Albert R. Reinke of Berkeley; nine grandchildren and one great-grandchild.Personal life

Stratton had several hobbies, brick-laying the most important one. He built the brick walls and paths in the garden of his house, a house he himself helped design. His daughter, Elenore, would recall decades later living in the house, with a view of the San Francisco bay and the Golden Gate on one side and the Marin county hills beyond. Annual camping in summer in the Sierras was another pastime, and he carried his love of books over there as well, writing in the shade of a tree in the mornings. Elenore also recalled his night-time reading of Homer to his children, mixing with fascinating guests for weekend suppers prepared by her mother, and the family camping out with Latin professor "Uncle" Leon Richardson.Work

Stratton began his career working in a philosophy department, teaching philosophy courses, but branched into experimentation soon after. He tackled problems of sociology and international relations later in his career.Wundt's lab and the inverted-glasses experiments

Stratton went on to become a first-generation experimentalist in psychology. Wundt's lab in Leipzig, with experimental programs bringing together the fields ofevolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes ( natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life ...

, sensory physiology and nervous-system studies, was a part of the career of most of the first generation. It was the exposure there, added to the graduate work at Yale, that influenced Stratton into becoming a psychologist. It was there that he started his binocular vision experiments as well. In these experiments, he found himself adapting to the new perception of the environment over a few days, after inverting the images his eyes saw on a regular basis. For this, he wore a set of upside down goggles

Upside down goggles, also known as "invertoscopes" by Russian researchers, are optical instruments that invert the image received by the retinas upside down. They are used to study human visual perception, particularly psychological process of bui ...

, glasses inverting images both upside-down and left-right. Stratton wore these glasses over his right eye and covered the left with a patch during the day, and slept blindfolded at night. Initial movement was clumsy, but adjusting to the new environment took only a few days.

Stratton tried variations of the experiment over the next few years. First he wore the glasses for eight days, back at Berkeley. The first day he was nauseated and the inverted landscape felt unreal, but by the second day just his own body position seemed strange, and by day seven, things felt normal. A sense of strangeness returned when the glasses were taken out, though the world looked straight side up; he found himself reaching out with the right hand when he should have used the left, and the other way around. Then he tried the experiment outdoors. He also tried another experiment disrupting the mental link between touch and sight. There he wore a set of mirrors attached to a harness as shown in the figure allowing, and forcing, him to see his body from above. He found the senses adapted in a similar way over three days. His interpretation was that we build up an association between sight and touch by associational learning over a period of time. During certain periods, the disconnect between vision and touch made him feel as if his body was not where his touch and proprioceptive feeling told him it was. This out-of-body experience, caused by an altered but normal sensory perception, vanished when he attended to the issue critically, focusing on the disconnect.

Berkeley psychology department

Back at Berkeley from Johns Hopkins, Stratton stayed in the philosophy department as its second faculty member and first psychology specialist until the psychology department broke off in 1922. The new department started with four people: Stratton as chair;Edward Chace Tolman

Edward Chace Tolman (April 14, 1886 – November 19, 1959) was an American psychologist and a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Through Tolman's theories and works, he founded what is now a branch of psychology know ...

, with a Harvard degree, and an initiator of rodent experiments soiling the rooms of the philosophy department and hastening the split of the psychology division; Brown, Stratton's earlier student and Berkeley faculty member from 1908 onward; and Olga Bridgman, the first Berkeley psychology PhD awardee, albeit from the philosophy department. Before the split Stratton had set up Berkeley's first psychology lab in the philosophy department and taught psychology courses with Brown. The courses included sensation, perception, emotion, memory, and applications of psychology to professions such as law, medicine, schooling and clerical work by priests.

Stratton continued his experiments on perception, branching into studies on pseudoscopic vision

A pseudoscope is a binocular optical instrument that reverses depth perception. It is used to study human stereoscopic perception. Objects viewed through it appear inside out, for example: a box on a floor would appear as a box-shaped hole in the ...

, stereoscopic acuity, eye movements, symmetry and visual illusions, how people perceive depth seeing surroundings either one-eyed or two-eyed, acuity and limits of peripheral vision

Peripheral vision, or ''indirect vision'', is vision as it occurs outside the point of fixation, i.e. away from the center of gaze or, when viewed at large angles, in (or out of) the "corner of one's eye". The vast majority of the area in th ...

, apparent motion, afterimages impressed on the eye when a person stares at an object for long and then looks away, and problems with sight in half the visual field (hemianopsia

Hemianopsia, or hemianopia, is a loss of vision or blindness ( anopsia) in half the visual field, usually on one side of the vertical midline. The most common causes of this damage are stroke, brain tumor, and trauma.

This article deals only wi ...

). He both reviewed earlier studies on motion and conducted two of his own, concluding perceiving movement was more than the sum of seeing successive sequential images. He also surveyed and reported in reviews in the ''Psychological Bulletin

The ''Psychological Bulletin'' is a monthly peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes evaluative and integrative research reviews and interpretations of issues in psychology, including both qualitative (narrative) and/or quantitative ( meta-an ...

'' experiments at various labs, including those in Europe, on matters related to sensation and perception.

* Philosophical Union: "The import of psychological experiments" (series), 1899–1900

* Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

annual address: "The fighting instinct", May 11, 1909

* Philosophical Union: "The philosophy and the world of ideals: Aesthetics", April 1, 1910

* Philosophical Union: "The psychology of mysticism", February 25, 1916

* Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Lectures: "The psychology of the war spirit" series, 1915 UC summer session

** June 21: "The external occasions of fighting"

** June 23: "The inner sources of combativeness"

** June 25: "The psychic condition of hostility"

** July 2: "Fighting among savages"

** July 7: "Psychology of the war spirit: Significant changes among leading people"

** July 9: "Psychology of the war spirit: The present quality of warfare"

** July 12: "Warfare and the great interests: Commerce and science"

** July 14: "Warfare and the great interests: Morality"

** July 16: "Warfare and the great interests"

** July 19, 21, 23, 26, 28, 30: "Methods of control in war"

* Yale Divinity School, New Haven: "Anger in morals and religion" (series of 4), May 1920

* Philosophical Union: 1921

** Jan 28: "Being mutually angry"

** Feb 11: "Experiments on the mind: Their character and value"

** Feb 18: "The subconscious and its importance"

** Feb 25: "The training of the will"

** Mar 4: "Where has psychology left religion"

** Mar 11: "The teachings of morals and religion"

* International Relations Lectures: "The orient and the armament conference", November 4, 1921

Philosophical and educational psychology and sociology

Stratton was exposed to multiple influences through his life. As an undergraduate student of Howison, he learned about philosophy and religion. At Yale and later at Wundt's lab, he switched to experimental psychology and studied perception, memory and emotion. His exposure to World War I, serving in the Army then, focused his mind on issues of war and peace and international relations. Stratton's later work reflected these elements of his experience. He was also a scholar of the classics and translated some Greek philosophers. Stratton saw humans not as machines to be analyzed mechanistically, but also as seating will, emotion and drives, all of which had to analyzed as scientifically as the traditional psychological concepts of sensation, perception and memory. He also believed in a supreme actuality behind the world registered by our senses. This was the theme of his last published book, ''Man-Creator or Destroyer'', completed in 1952 when he was eighty-seven years old. His book ''Developing Mental Power'' was a foray into educational psychology, addressing the question of general versus specific training in terms teachers could understand and use. Stratton aimed at this goal via a simple and generally applicable look at the basic workings of mental life. John F. Dashiell, writing in the ''Journal of Abnormal Psychology'', found this a failure. Dashiell saw the path from the psychological concepts—emotion, intelligence, and will—to teaching methodology, not clearly described in the book. Stratton also applied psychological concepts to figure out how to avert war. He was optimistic it was possible to harness the creative and destructive facets of individuals to get nations to coexist peacefully. He saw nations as consisting of ethnicities and races which had to coexist in harmony. In line with the prevailing view in his field, he did not see the races as inherently equally intelligent.Psychology of religion and emotions

Stratton also contributed to the psychological study of religion. Along with other founders of thepsychology of religion

Psychology of religion consists of the application of psychological methods and interpretive frameworks to the diverse contents of religious traditions as well as to both religious and irreligious individuals. The various methods and frameworks ...

, he saw religion as including both personal faith and historical traditions. He used religious texts as supporting data. In ''The Psychology of the Religious Life'' he explored the epics and sacred texts

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

of a large set of ethnicities to understand the traditions and rituals symbolizing the concrete parts of faiths to understand the goals and concept of religion as a whole. His psychology sought to explain how our need to grasp, accept and live with conceptual opposites such as the sublime and the devilish, the humble and the proud, and the docile and the energetic, led us in the direction of religion. He also tied human emotions, especially anger and pugnacity, to religious faith. To understand the linkage, Stratton collected data on religious writings and the rites and traditions of civilizations then considered not as advanced. In ''Anger: Its Religious and Moral Significance'' he listed exhaustively and studied the major religions of the world and classified them into three categories. The combative religions, such as Islam, per him, glorified anger, while those such as Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

were "unangry". Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

he saw as an example of an anger-supported-love based religion. He concluded Western civilization

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

was trending toward denying rage as good and accepting love and goodwill as desirable, but cautioned anger was at times needed to fight evil.

As a professor at Berkeley, Stratton visited Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, China, Japan, and Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

, coordinating with the University of the Philippines

The University of the Philippines (UP; fil, Pamantasan ng Pilipinas Unibersidad ng Pilipinas) is a state university system in the Philippines. It is the country's national university, as mandated by Republic Act No. 9500 (UP Charter of 20 ...

to study the psychology of both races and oriental religions. He also explored anger and emotions in animals. He was one of the scientists who were invited to attend, and confirmed attendance, at a conference to discuss human emotions and feelings. The conference, scheduled for October 21–23, 1927 at Wittenberg College

Wittenberg University is a private liberal arts college in Springfield, Ohio. It has 1,326 full-time students representing 33 states and 9 foreign countries. Wittenberg University is associated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Americ ...

, Springfield, Ohio also was to focus on the experimental psychology of religion.

Stratton articulated his own beliefs about religion as well. He did not subscribe to the view religious feeling was primarily a social need, believing it to be a need for seeing a cause and logic to the world along with a harmony to things. A believer in dualism, he held the theory of a separate biological psyche and something beyond it. To him the most important aspects of the psyche lay beyond objective science, at least in his time. He sought to explore those boundaries where the methods of science had to stop and declare what was beyond as unknown, limited by the tools of the times. In ''The Psychology of the Religious Life'' he laid out his definition of religion as an appreciative feeling toward an unseen entity marked the best or the greatest.

Stratton suggested music had healing powers. In an address on the "Nature and training of the emotions" delivered to a group of nurses at the Baltimore hospitals, he predicted music would be used to treat the sick in the future, and held that nurses had to know how to sing to patients under their care.

Books

Stratton wrote eight books, and contributed to collections honoring his mentors, writing an obituary on Wundt and a biography of Howison. His PhD thesis, ''Über die Wahrnehmung von Druckänderungen bei verschiedenen Geschwindigkeiten'', was in German and published in Leipzig in Wundt's '' Philosophische Studien'', XII Band, IV Heft. His first book. ''Experimental Psychology and its Bearing upon Culture'' covered the scope and practice of experimental psychology, and later books turned more toward sociology and international relations.Experimental Psychology and its Bearing upon Culture

Stratton wrote ''Experimental Psychology and its Bearing upon Culture'' to explain both typical psychological experiment methodology and how the results obtained answered philosophical problems. The book covered experimental results in psychology and how they influenced overall social behavior and the everyday cultural life of people. It did so by looking at the history of experimental psychology, and then surveying experimental methods covering both their applications and limits. Stratton pointed out how psychological experiments differed from the ones in physiology. The survey of experiments also included studies on mental perception, including among the blind. Stratton noted that the blind did have a sense of space. He also described how measurements of mental phenomena were both possible and being done in practice, though he did believe the results had to be interpreted on a psychic scale different from the usual physical ones used for measures such as lengths and weights. He rejected the argument the mind was unitary and could not be studied by splitting it into parts, by drawing on the analogy of studying a tree by looking at its constituent parts, themselves not functionally trees. He presumed sensations were akin to trees in how they could be split up into parts. The book had chapters on memory, imitation and suggestion, perceptual illusions, and esthetics. In these he refuted the idea that experience was just the external environment acting on and molding a mind working as a passive recipient. Stratton saw the sensation of time as being multidimensional, in analogy with perception of space. That we could simultaneously hear separately, without synthesizing, multiple mixed tones meant our experiences did not necessarily come in single file temporally. To Stratton this meant time had multiple dimensions, since simultaneous events could not be distinguished on the one past-present-future dimension of time alone. He did not address how the other dimensions could be in temporal-space if the events were indistinguishable temporally to begin with. He also analyzed poetic measure as mathematically connected to the waxing and waning span of attention, tying the arts to psychology. This last was rebutted byCharles Samuel Myers

Charles Samuel Myers, CBE, FRS (13 March 1873 – 12 October 1946) was an English physician who worked as a psychologist. Although he did not invent the term, his first academic paper, published by ''The Lancet'' in 1915, concerned ''shell sh ...

, writing in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'', who saw poetry and its rhythm as too complex a subject to be reduced to the arithmetic of attention spans.

In later chapters, Stratton covered the topics of the unconscious mind, the mind–body connection, and spiritual aspects of psychology. He attacked the standard dualist view of a separate homuncular entity driving the biology of mental processes. Still he concluded, from observations that people were not always aware of how their own perception differed from sensory reality, that a diluted form of the dualist theory was tenable. In his final chapter, the author posited experimental psychology neither needed nor ruled out the idea of a soul. Myers critiqued the book's treatment of illusions, memory, and relationship of psychology to body and soul, as not addressing the broader aspect of "culture". Myers saw the work as appealing more to the educated reader than the specialist, the many deviations from experimental topics into subjective arenas a distraction.

Social Psychology for International Conduct

Stratton wrote ''Social Psychology for International Conduct'' forsocial science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of so ...

teachers who wanted to use psychology to analyze international affairs. The book's first part evaluated races. Stratton concluded the Caucasoid

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid or Europid, Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of human beings based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, de ...

and Mongoloid

Mongoloid () is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms ...

races were innately more intelligent enabling them to build strong cultures. He also stated the prejudice of other people was from the social and political advantages it brought. Stratton saw nations as made up of individuals and possessing a national character similar to what individuals had. Reviewing the book in the '' American Journal of Sociology'', Ellsworth Faris objected to the author concluding the Northern and Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

ans were more intelligent than Southern and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

ans, noting intelligence measures correlated also with length of stay in America.

In the chapter on "Taking national profits out of war" the author hypothesized nations often went to war because it paid, bringing both national rewards and helping achieve policy goals. He suggested nations be blocked from enjoying any fruits of war, and instead be penalized for waging it. In a review in the ''Political Science Quarterly

''Political Science Quarterly'' is an American double blind peer-reviewed academic journal covering government, politics, and policy, published since 1886 by the Academy of Political Science. Its editor-in-chief is Robert Y. Shapiro (Columbia U ...

'', Walter Sandelius concluded enforcing such a position meant an international enforcement force with judicial and police powers, the formation of which would need an appeal to both reason and desire on the part of the international community. Sandelius also saw Stratton as pushing more for re-educating the mind rather than training people to control emotions and passions in the efforts to avert war.

What Starts Wars: Intentional Delusions

In ''What Starts Wars: Intentional Delusions'' Stratton presented nations, themselves collections of people, as triggering war from several delusions. Three of those delusions held by citizens were that their own country was a paragon of peace, that its arms were only to defend the land, and that when it fought, it fought only for what was right. Blaming the enemy rounded out this list justifying war. Stratton believed and stated people could be freed of these delusions and that there was no will to war integral to human nature. He saw both the need for and the ways to eliminate war in individuals and in their ways, and not in abstract or innate traits.Florence Finch Kelly

Florence Finch Kelly (March 27, 1858 – December 17, 1939) was an American feminist, suffragist, journalist and author of novels and short stories.

Biography

Florence Finch was born in Girard, Illinois, March 27, 1858. She was the youngest chi ...

, reviewing the book for the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', saw Stratton's placing of both the blame and the responsibility on persons, of identifying the roots of war in the psyches of the men and women his readers, as an action likely to discomfit those readers.

Legacy

Stratton became a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1928, president of the American Psychological Association in 1908, chair of its division on anthropology and psychology in 1925-–1926, was a member of its National Research Council, an honorary member of the National Institute of Psychology, and a corresponding member of the American Institute of Czechoslovakia. He published eight full-length books, and 125 papers. He was an honorary lecturer at Yale, delivering the Nathaniel W. Taylor Lectures at the Yale School of Religion beginning April 19, 1920. Stratton's earlier work on sensation and perception and the book based on them stayed influential among researchers in psychology. Many of his other books and articles which dealt with philosophical and sociological issues either beyond, or treated via perspectives beyond, exact and objective investigation had lost appeal to psychology researchers by the time of his death. Of the various fields Stratton studied, it is his experimentation in binocular vision and perception that has had the most impact. Whether during the inversion experiment people really see an upside-down world as being normal, or whether they adapt to it only behaviorally, has been debated for a long time.Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is the use of quantitative (computational) techniques to study the structure and function of the central nervous system, developed as an objective way of scientifically studying the healthy human brain in a non-invasive manner. Incr ...

studies done a century after the original experiment have shown no difference in early levels of visual processing, which indicates the perceptual world stays inverted at that level of cognition. The research has been put to use in both practical and esthetic ways. The mirror-experiment experience of disconnect between vision and feeling has parallels in, and applications for researching, phantom limb syndrome. The art exhibit ''Upside-down Mushroom Room'' by Belgian artist Carsten Höller

Carsten Höller (born December 1961) is a German artist. He lives and works in Stockholm, Sweden.Alice Rawsthorn (January 2012)"Cliff Hanger - The Ghanaian home of artists Carsten Höller and Marcel Odenbach goes above—and beyond" ''W Magazi ...

, a tunnel installation with an inverted environment, builds on Stratton's work.

Stratton provided encouragement to both his students and his children. Early at Berkeley, he encouraged young students to pursue graduate study in psychology, writing personal letters to students who scored an A grade in his introductory psychology course. The stamp of Stratton's legacy can be seen in his doctoral students. Knight Dunlap was one of his earliest students at Berkeley and he became the twenty-second president of the American Psychological Association. Dunlap was one of those who saw Stratton as a guide and mentor. Another of his early students, Warner Brown, would be the chair of the psychology department at Berkeley for sixteen years. A third, Olga Bridgman, would serve on the faculty at University of California—Berkeley and San Francisco—for over forty years.

Committees

* Standing Committees of the Academic Council for Scholarships, University of California, 1902–1903 * Standing Committees of the Graduate Council: University of California, 1902–1903 * One of the first group of members of the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology (SSFY), 1904 * President of the American Psychological Association, 1908 * Committee of Arrangements for Administering the Beale Prizes instituted by Regent Truxtun Beale, 1911 * Chair of Board of Research, University of California, 1920–1921 * Chair of the University of California Meeting, October 7, 1921 * Standing Committee of the Academic Senate, Administrative Committee on International Relations, 1921–1922 * Elected member of the National Academy of Sciences, 1928. Stratton served in various capacities with the NAS: ** Member of the National Research Council, 1925–1926 ** Chair of Division of Anthropology and Psychology, National Research Council, 1926 **Member of the Board for administering the Rockefeller Foundation fellowships in the biological sciences, 19245–1926 ** Representative on Editorial board of PNAS, 1926 ** Advisory board of the Bureau of Public Personnel Administration of the Institute for Government Research, 1926 ** Committee on Tactual Interpretation of Oral Speech and Vocal control by the Deaf, 1926 ** Committee on National fellowships in Child Development, 1927List of books

* * * * * * * * * *See also

*Neural adaptation

Neural adaptation or sensory adaptation is a gradual decrease over time in the responsiveness of the sensory system to a constant stimulus. It is usually experienced as a change in the stimulus. For example, if a hand is rested on a table, the ta ...

* Peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals, such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world peac ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

Books * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Journals * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Newspapers and magazines * * * * * * * Web sources * * * * * * * *Bibliography notes

External links

Open Library: George Stratton books free online

Social Psychology of International Conduct

Full text of PhD thesis (German)

Ancestry.com records

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stratton, George M. American social psychologists Psychologists of religion Emotion psychologists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences University of California, Berkeley alumni Yale University alumni Leipzig University alumni University of California, Berkeley faculty Johns Hopkins University faculty Yale Divinity School faculty United States Army officers People from Oakland, California People from Berkeley, California People from Baltimore 1865 births 1957 deaths Presidents of the American Psychological Association Vision scientists Military personnel from California