George Grenville on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

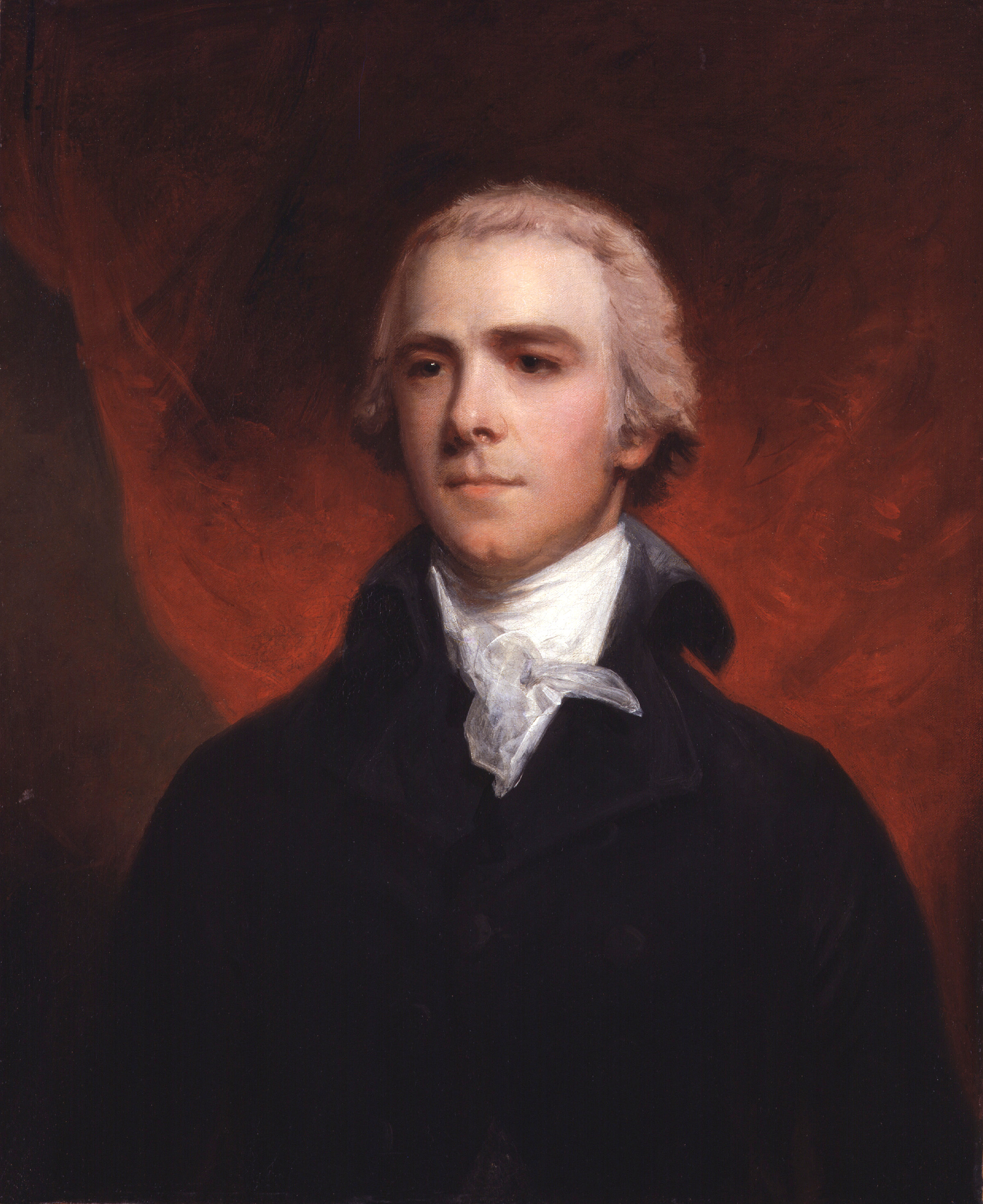

George Grenville (14 October 1712 – 13 November 1770) was a British Whig statesman who served as

George Grenville was born at Wotton House on 14 October 1712. He was the second son of Sir Richard Grenville and Hester Temple (later the 1st Countess Temple). He was one of five brothers, all of whom became MPs. His sister Hester Grenville married the leading political figure

George Grenville was born at Wotton House on 14 October 1712. He was the second son of Sir Richard Grenville and Hester Temple (later the 1st Countess Temple). He was one of five brothers, all of whom became MPs. His sister Hester Grenville married the leading political figure

In 1749 Grenville married Elizabeth Wyndham (1719 – 5 December 1769), daughter of Sir William Wyndham, and the granddaughter of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset. Somerset did not approve of their marriage and consequently left Elizabeth only a small sum in his will.

In 1749 Grenville married Elizabeth Wyndham (1719 – 5 December 1769), daughter of Sir William Wyndham, and the granddaughter of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset. Somerset did not approve of their marriage and consequently left Elizabeth only a small sum in his will.

Bibliography of source material:

* Lawson, P. George Grenville: A Political Life. Oxford 1984.

* Wiggin, L. M. The Faction of Cousins: a Political Account of the Grenvilles 1733–1763. New Haven, 1958. The couple had four sons and four daughters.See pedigrees in Beckett 1994, p. 35; and in (One account states they had five daughters.) # Richard Grenville (died 1759), died young # George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham (17 June 1753 – 11 February 1813), father of the 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos # Charlotte Grenville ( – 29 September 1830), married Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, 4th Baronet (1749–1789) on 21 December 1771, and had eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood # Thomas Grenville (31 December 1755 – 17 December 1846), MP and bibliophile, died unmarried # Elizabeth Grenville (24 October 1756 – 21 December 1842), married (as his second wife) John Proby, 1st Earl of Carysfort (1751–1828), on 12 April 1787, and had three daughters # William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville (25 October 1759 – 12 January 1834), later Prime Minister # Catherine Grenville (1761 – 6 November 1796), married Richard Neville-Aldworth (1750–1825), afterwards Richard Griffin, 2nd Baron Braybrooke, on 19 June 1780, and had four children. # Hester Grenville (before 1767 – 13 November 1847), married Hugh Fortescue, 1st Earl Fortescue, on 10 May 1782 and had nine children At the time of his death in 1770, he was the

Prime Minister of Great Britain

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet, and selects its ministers. Modern pr ...

, during the early reign of the young George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

. He served for only two years (1763-1765), and attempted to solve the problem of the massive debt resulting from the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. He instituted a series of measures to increase revenue to the crown, including new taxes and enforcement of collection, and sought to bring the North American colonies under tighter crown control.

Born into an influential political family, Grenville first entered Parliament in 1741 as an MP for Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

. He emerged as one of the Cobhamites, a group of young members of Parliament associated with Lord Cobham. In 1754, Grenville became Treasurer of the Navy, a position he held twice until 1761. In October 1761 he chose to stay in government and accepted the new role of Leader of the Commons causing a rift with his brother-in-law and political ally William Pitt who had resigned. Grenville was subsequently made Northern Secretary and First Lord of the Admiralty by the new prime minister Lord Bute

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (; 25 May 1713 – 10 March 1792), styled Lord Mount Stuart between 1713 and 1723, was a British Tories (British political party), Tory statesman who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Prime Mini ...

. On 8 April 1763, Lord Bute resigned, and Grenville assumed his position as prime minister.

His government tried to bring public spending under control and pursued an assertive policy over the North American colonies and colonial settlers. His best-known policy is the Stamp Act, a long-standing tax in Great Britain which Grenville extended to the colonies in America, but which instigated widespread opposition in Britain's American colonies and was later repealed. Grenville had increasingly strained relations with his colleagues and the King. In 1765, he was dismissed by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

and replaced by Lord Rockingham. For the last five years of his life, Grenville led a group of his supporters in opposition and staged a public reconciliation with Pitt.

Grenville married Elizabeth Wyndham, the granddaughter of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, the great-great-grandson of Lady Katherine Grey, who was herself a great-granddaughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, and sister of Lady Jane Grey.

Early life: 1712-1741

Family

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British people, British British Whig Party, Whig politician, statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him "Chatham" or "Pit ...

. His elder brother was Richard Grenville, later the 2nd Earl Temple. It was intended by his parents that George Grenville should become a lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

.

Education

Grenville was educated atEton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

and at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, but did not graduate.

Early political career: 1741-1756

Member of Parliament

He enteredParliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in 1741 as one of the two members for Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

, and continued to represent that borough for the next twenty-nine years until his death. He was disappointed to be giving up what appeared to be a promising legal career for the uncertainties of opposition politics.

In Parliament, he subscribed to the "Boy Patriot" party, which opposed Sir Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

. In particular he enjoyed the patronage of his uncle Lord Cobham, the leader of a faction that included George Grenville, his brother Richard, William Pitt and George Lyttelton that became known as the Cobhamites.

Administration

In December 1744 he became a Lord of the Admiralty in the administration of Henry Pelham. He allied himself with his brother Richard and with William Pitt (who became their brother-in-law in 1754) in forcing Pelham to give them promotion by rebelling against his authority and obstructing business. In June 1747, Grenville became a Lord of the Treasury. In 1754 Grenville was made Treasurer of the Navy and Privy Councillor. Along with Pitt and several other colleagues he was dismissed in 1755 after speaking and voting against the government on a debate about a recent subsidy treaty withRussia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

which they believed was unnecessarily costly, and would drag Britain into Continental European disputes. Opposition to European entanglements was a cornerstone

A cornerstone (or foundation stone or setting stone) is the first stone set in the construction of a masonry Foundation (engineering), foundation. All other stones will be set in reference to this stone, thus determining the position of the entir ...

of Patriot Whig thinking.

He and Pitt joined the opposition, haranguing the Newcastle government. Grenville and Pitt both championed the formation of a British militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

to provide additional security rather than the deployment of Hessian mercenaries favoured by the government. As the military situation deteriorated following the loss of Minorca, the government grew increasingly weak until it was forced to resign in Autumn 1756.

In Government: 1756-1763

Treasurer of the Navy

Pitt then formed a government led by the Duke of Devonshire. Grenville was returned to his position as Treasurer of the Navy, which was a great disappointment as he had been expecting to receive the more prestigious and lucrative post ofPaymaster of the Forces

The Paymaster of the Forces was a position in the British government. The office was established in 1661, one year after the Restoration (1660), Restoration of the Monarchy to Charles II of England, and was responsible for part of the financin ...

. This added to what Grenville regarded as a series of earlier slights in which Pitt and others had passed him over for positions in favour of men he considered no more talented than he was. From then on Grenville felt a growing resentment towards Pitt, and grew closer to the young Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

and his advisor Lord Bute

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (; 25 May 1713 – 10 March 1792), styled Lord Mount Stuart between 1713 and 1723, was a British Tories (British political party), Tory statesman who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Prime Mini ...

who were both now opposed to Pitt.

In 1758, as Treasurer of the Navy, he introduced and carried a bill which established a fairer system of paying the wages of seamen and supporting their families while they were at sea which was praised for its humanity if not for its effectiveness. He remained in office during the years of British victories, notably the Annus Mirabilis of 1759 for which the credit went to the government of which he was a member. However his seven-year-old son died after a long illness and Grenville remained by his side at their country house in Wotton and rarely came to London.

In 1761, when Pitt resigned upon the question of the war with Spain, and subsequently functioned as Leader of the House of Commons

The Leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons. The Leader is always a memb ...

in the administration of Lord Bute

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (; 25 May 1713 – 10 March 1792), styled Lord Mount Stuart between 1713 and 1723, was a British Tories (British political party), Tory statesman who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Prime Mini ...

. Grenville's role was seen as an attempt to keep someone closely associated with Pitt involved in the government, in order to prevent Pitt and his supporters actively opposing the government. However, it soon led to conflict between Grenville and Pitt. Grenville was also seen as a suitable candidate because his reputation for honesty meant he commanded loyalty and respect amongst independent MPs.

Northern Secretary

In May 1762, Grenville was appointed Northern Secretary, where he took an increasingly hard line in the negotiations with France and Spain designed to bring theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

to a close.

Grenville demanded much greater compensation in exchange for the return of British conquests, while Bute favored a more generous position which eventually formed the basis of the Treaty of Paris. In spite of this, Grenville had now become associated with Bute rather than his former political allies who were even more vocal in their opposition to the peace treaty than he was. In October he was made First Lord of the Admiralty. Henry Fox took over as Leader of the Commons, and forced the peace treaty through parliament.

Bute's position grew increasingly untenable as he was extremely unpopular, which led to him offering his resignation to George III on several occasions. Bute was the target of the radical John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

's criticism and satire. He was ridiculed in Wilkes' newspaper '' The North Briton'', a stereotypical reference to the prime minister's Scottish heritage.

Prime Minister: 1763-1765

Appointment

Bute's intention to resign was genuine, and the hostile press attacks and the continuing unpopularity of his government finally led to King George III to reluctantly accept his resignation. Though the king was unsure whom should be appoint to the position and Bute highly recommended that the King should appoint Grenville as the new prime minister. Despite the King's disapproval and distrust of his ministers, he considered appointing Grenville to office. When Grenville was asked about becoming the new prime minister, he agreed only on the condition that Bute would not take an active part in politics and be barred from voicing policies for the government. The King agreed and thus appointed Grenville as new prime minister. George III assured Grenville that "he meant to put his government solely into his hand". Grenville set to work and formed his government on 16 April 1763. He appointed two of his trusted allies Lord Halifax and Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont as Northern Secretary and Southern Secretary respectively. He also appointed the Lord Northington as Lord High Chancellor, Lord Granville as Lord President of the Council as well.Domestic issues

Arrest of John Wilkes

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

was thrown into doubt by the first case involving the Member of Parliament John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

, a radical reformer and political activist who promoted parliamentary representation and reform, whose critique of the former prime minister led to his resignation.

Wilkes was regarded by many as threat to the government and therefore was treated suspiciously. In 1763, it came to be one of Grenville's first acts to prosecute Wilkes for publishing in '' The North Briton'' newspaper an article deriding King George III's speech made on 23 April 1763. Wilkes was prosecuted for " seditious libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

". That was a massive tactical blunder by the secretaries of state, for it was perceived as a violation of individual liberty that raised the political discontent.

After fighting a duel with a supporter of the Grenville ministry, Samuel Martin, Wilkes fled to France for asylum. Despite government officials calling on him to be arrested, Wilkes was later returned to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and was elected and re-elected by the Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

constituency. He was continually refused admission to parliament by parliament, and proved a problem to several successive governments.

Monetary debt

The time of theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

was a tumultuous period in the history of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and was fought on a global conflict scale. Even though Great Britain defeated France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and its allies and rose to the position as a dominant world power, the victory came at a great cost. In January 1763, Great Britain's national debt was more than £122 million pounds, an enormous sum for the time. Interest on the debt was more than £4.4 million a year. Figuring out how to pay the interest alone absorbed the attention of the King and his ministers.

As Britain was trying to recover from the costs of the Seven Years' War and now in dire need of finances for the British army in the American colonies, Grenville's most immediate task was to restore the nation's finances. He also had to deal with the fall-out from Pontiac's Rebellion, which erupted in North America in 1763. Although, initially, prominent measures of his government included the prosecution of John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

, focus shifted from arresting radicals to paying off the national debt. The passing of the tax measures in America had proved to be a disaster and would lead to the first symptoms of alienation between American colonies and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

.

Colonial reforms

Measures and taxes

Many of the acts passed by the British were perceived by the colonists as threatening to their liberties. Although not a part of the Grenville government's programme, the issue was generally attributed to him by the colonists. Another one of the most controversial acts passed by Grenville was the Quartering Act on 15 May 1765. Enacted because of a request by Major General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief in North America, to give better housing for his troops stationed in the colonies. One of the more prominent measures of the Grenville's government occurred in March 1765 when Grenville authored theStamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. 3. c. 12), was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British America, British coloni ...

, enacted in November of that year. It was an exclusive tax placed on the colonies in America requiring that documents

A document is a written, drawn, presented, or memorialized representation of thought, often the manifestation of non-fictional, as well as fictional, content. The word originates from the Latin ', which denotes a "teaching" or "lesson": ...

and newspapers

A newspaper is a Periodical literature, periodical publication containing written News, information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background. Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as poli ...

be printed on stamped paper from London bearing an embossed revenue stamp that had to be paid for in British currency. It was met with general outrage and resulted in public acts of disobedience and riot

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

ing throughout the colonies in America.

Foreign policy

The signing of the treaty in February 1763 formally marked the conclusion of theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

experienced by Britain and as such, foreign policy, along with military policy and diplomacy, no longer became the dominant concern of both domestic politics and government agenda. Focus thus shifted to seemingly more relevant issues such as the survival of the Grenville Ministry. But overall the British relations, after negotiating, with the French and the Spanish, remained hostile and suspicious of its enemies and that wariness concluded the entirety of Grenville's policy.

When seemingly, the French and the Spanish began to support Britain's colonial dissenters in the Americas and beyond and threatening British allies in the continent, promoting disputes and resentment from British politicians who viewed them as a violation of British sovereignty. Britain begun a process of isolation, when Britain had no allies in the continent and the allies it did have were weak or less significant in military or political might.

In disputes with Spain and France, Grenville managed to secure British objectives by deploying what was later described as gunboat diplomacy. During his ministry. Britain's international isolation increased, as Britain failed to secure alliances with other major European powers, a situation that subsequent governments were unable to reverse leading to Britain fighting several countries during the American War of Independence without a major ally.

Dismissal

The King made various attempts to induce Pitt to come to his rescue by forming a ministry, but without success. George at last had recourse to Lord Rockingham. When Rockingham agreed to accept office, the king dismissed Grenville in July 1765. He never again held office. The nickname of "gentle shepherd" was given him because he bored the House by asking over and over again, during the debate on the Cider Bill of 1763, that somebody should tell him "where" to lay the new tax if it was not to be put on cider. Pitt whistled the air of the popular tune (by Boyce) ''Gentle Shepherd, tell me where'', and the House laughed. Though few surpassed him in knowledge of the forms of the House or in mastery of administrative details, he lacked tact in dealing with people and affairs.Later life: 1765-1770

In Opposition

After a period of active opposition to the Chatham Ministry led by Pitt between 1766 and 1768, Grenville became an elder statesman during his last few years – seeking to avoid becoming associated with any faction or party in the House of Commons. He was able to oversee the re-election of his core group of supporters in the 1768 General Election. His followers included Robert Clive and Lord George Sackville and he received support from his elder brother Lord Temple. In late 1768 he reconciled with Pitt and the two joined forces, re-uniting the partnership that had broken up in 1761 when Pitt had resigned from the government. Grenville was successful in mobilising the opposition during the Middlesex election dispute. Grenville prosecuted John Wilkes and the printers and authors for treason and sedition for publishing a bitter editorial about King George III's recent speech in "The North Briton" a weekly periodical. After losing the case Grenville lost favor from the public who regarded the act as an attempt to silence or control the press.Advocate and critic

Although personally opposed to Wilkes, Grenville saw the government's attempt to bar him from the Commons as unconstitutional and opposed it on principle. Following a French invasion of Corsica in 1768 Grenville advocated sending British support to theCorsican Republic

The Corsican Republic () was a short-lived state on the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea. It was proclaimed in July 1755 by Pasquale Paoli, who was seeking independence from the Republic of Genoa. Paoli created the Corsican Constitutio ...

. Grenville was critical of the Grafton Government's failure to intervene and he considered such weakness would encourage the French. In the House of Commons he observed "For fear of going to war, you will make a war unavoidable".

In 1770 Grenville steered a bill concerning the results of contested elections, a major issue in the eighteenth century, into law – despite strong opposition from the government.

Death

Grenville died on 13 November 1770, aged 58. His personal following divided after his death, with a number joining the government of Lord North. In the long-term, the Grenvillites were revived by William Pitt the Younger who served as prime minister from 1783 and dominated British politics until his death in 1806. Grenville's own son, William Grenville, later served briefly as prime minister. Grenville is buried at Wotton Underwood in Buckinghamshire''GrenODNB''. George Grenville's post mortem was carried up by John Hunter who retained specimens in his collection which later became the Hunterian Museum. Subsequent analysis of these specimens published by the Royal College of Surgeons of England suggests that George Grenville was affected byMultiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma (MM), also known as plasma cell myeloma and simply myeloma, is a cancer of plasma cells, a type of white blood cell that normally produces antibody, antibodies. Often, no symptoms are noticed initially. As it progresses, bone ...

at the time of his death.

Legacy

He was one of the relatively few prime ministers (others include Henry Pelham, William Pitt the Younger, Spencer Perceval, George Canning, Sir Robert Peel,William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

, Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

, Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

, Sir Winston Churchill, Sir Edward Heath, Sir John Major, Sir Tony Blair, Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Previously, he was Chancellor of the Ex ...

, Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

, Liz Truss

Mary Elizabeth Truss (born 26 July 1975) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from September to October 2022. On her fiftieth da ...

and Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (born 12 May 1980) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2022 to 2024. Following his defeat to Keir Starmer's La ...

) who never acceded to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

.

The town of Grenville, Quebec, was named after George Grenville. The town is in turn the namesake for the Grenville orogeny, a long-lived Mesoproterozoic mountain-building event associated with the assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia

Rodinia (from the Russian родина, ''rodina'', meaning "motherland, birthplace") was a Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic supercontinent that assembled 1.26–0.90 billion years ago (Ga) and broke up 750–633 million years ago (Ma). wer ...

. Its record is a prominent orogenic belt which spans a significant portion of the North American continent, from Labrador to Mexico, and extends to Scotland.

Family life

In 1749 Grenville married Elizabeth Wyndham (1719 – 5 December 1769), daughter of Sir William Wyndham, and the granddaughter of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset. Somerset did not approve of their marriage and consequently left Elizabeth only a small sum in his will.

In 1749 Grenville married Elizabeth Wyndham (1719 – 5 December 1769), daughter of Sir William Wyndham, and the granddaughter of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset. Somerset did not approve of their marriage and consequently left Elizabeth only a small sum in his will.Bibliography of source material:

* Lawson, P. George Grenville: A Political Life. Oxford 1984.

* Wiggin, L. M. The Faction of Cousins: a Political Account of the Grenvilles 1733–1763. New Haven, 1958. The couple had four sons and four daughters.See pedigrees in Beckett 1994, p. 35; and in (One account states they had five daughters.) # Richard Grenville (died 1759), died young # George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham (17 June 1753 – 11 February 1813), father of the 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos # Charlotte Grenville ( – 29 September 1830), married Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, 4th Baronet (1749–1789) on 21 December 1771, and had eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood # Thomas Grenville (31 December 1755 – 17 December 1846), MP and bibliophile, died unmarried # Elizabeth Grenville (24 October 1756 – 21 December 1842), married (as his second wife) John Proby, 1st Earl of Carysfort (1751–1828), on 12 April 1787, and had three daughters # William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville (25 October 1759 – 12 January 1834), later Prime Minister # Catherine Grenville (1761 – 6 November 1796), married Richard Neville-Aldworth (1750–1825), afterwards Richard Griffin, 2nd Baron Braybrooke, on 19 June 1780, and had four children. # Hester Grenville (before 1767 – 13 November 1847), married Hugh Fortescue, 1st Earl Fortescue, on 10 May 1782 and had nine children At the time of his death in 1770, he was the

heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

to the Earldom of Temple held by his elder brother Richard (who had succeeded their mother in that title in 1752, but had no sons). When Richard died in 1779, George's second (but eldest surviving) son, also George, therefore succeeded as 3rd Earl Temple, and was later created Marquess of Buckingham. His male line survived until the death of the 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos in 1889.

See also

* GrenvilliteReferences

Attribution *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Grenville, George 1712 births 1770 deaths Younger sons of earls People educated at Eton College Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Prime ministers of Great Britain Secretaries of state for the Northern Department Chancellors of the Exchequer of Great Britain Lords of the Admiralty Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies British MPs 1741–1747 British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 British MPs 1761–1768 British MPs 1768–1774 George Grenville Parents of prime ministers of the United Kingdom Leaders of the House of Commons of Great Britain Whig members of the Parliament of Great Britain Whig prime ministers of the United Kingdom Deaths from multiple myeloma in England