George Washington Carver on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

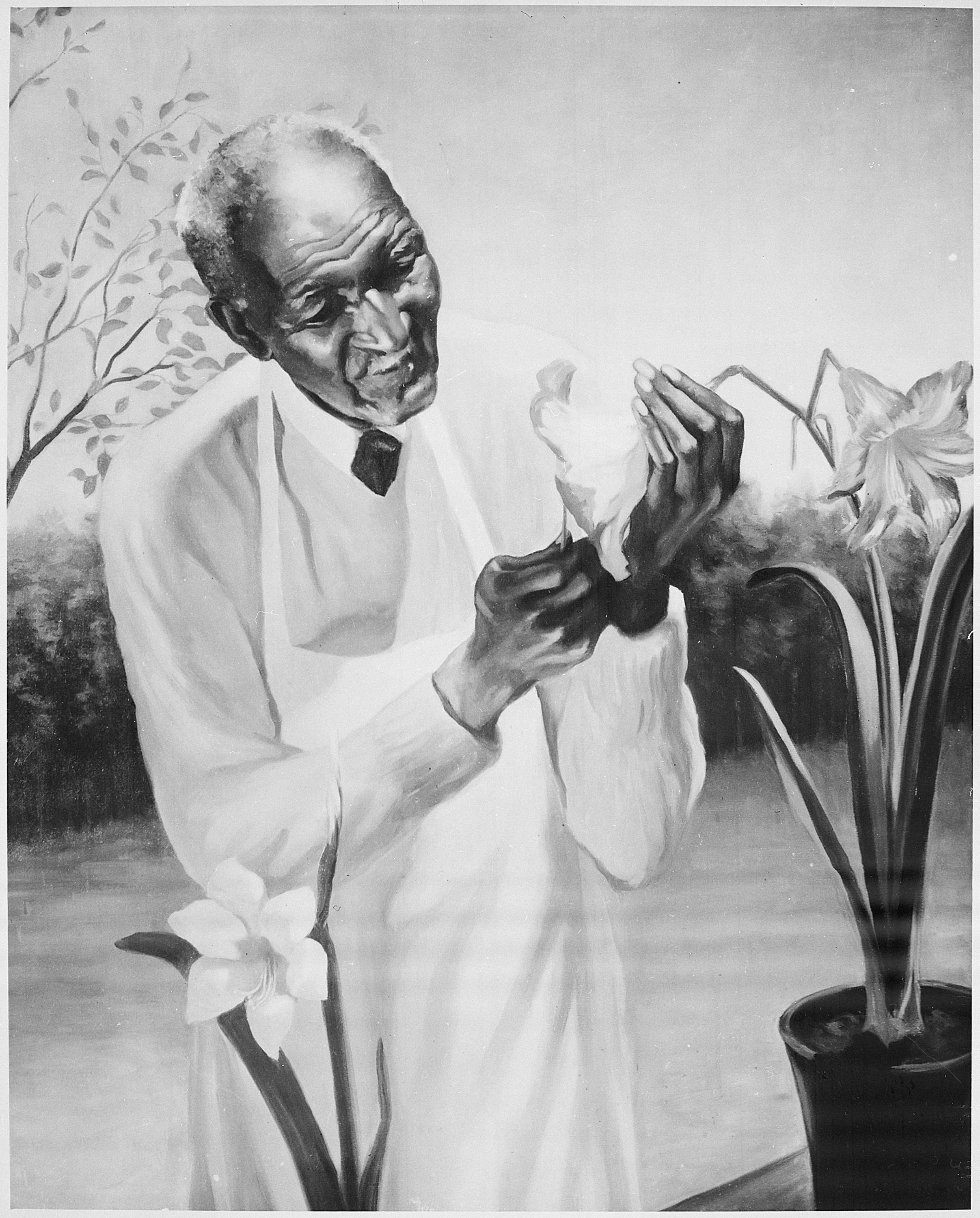

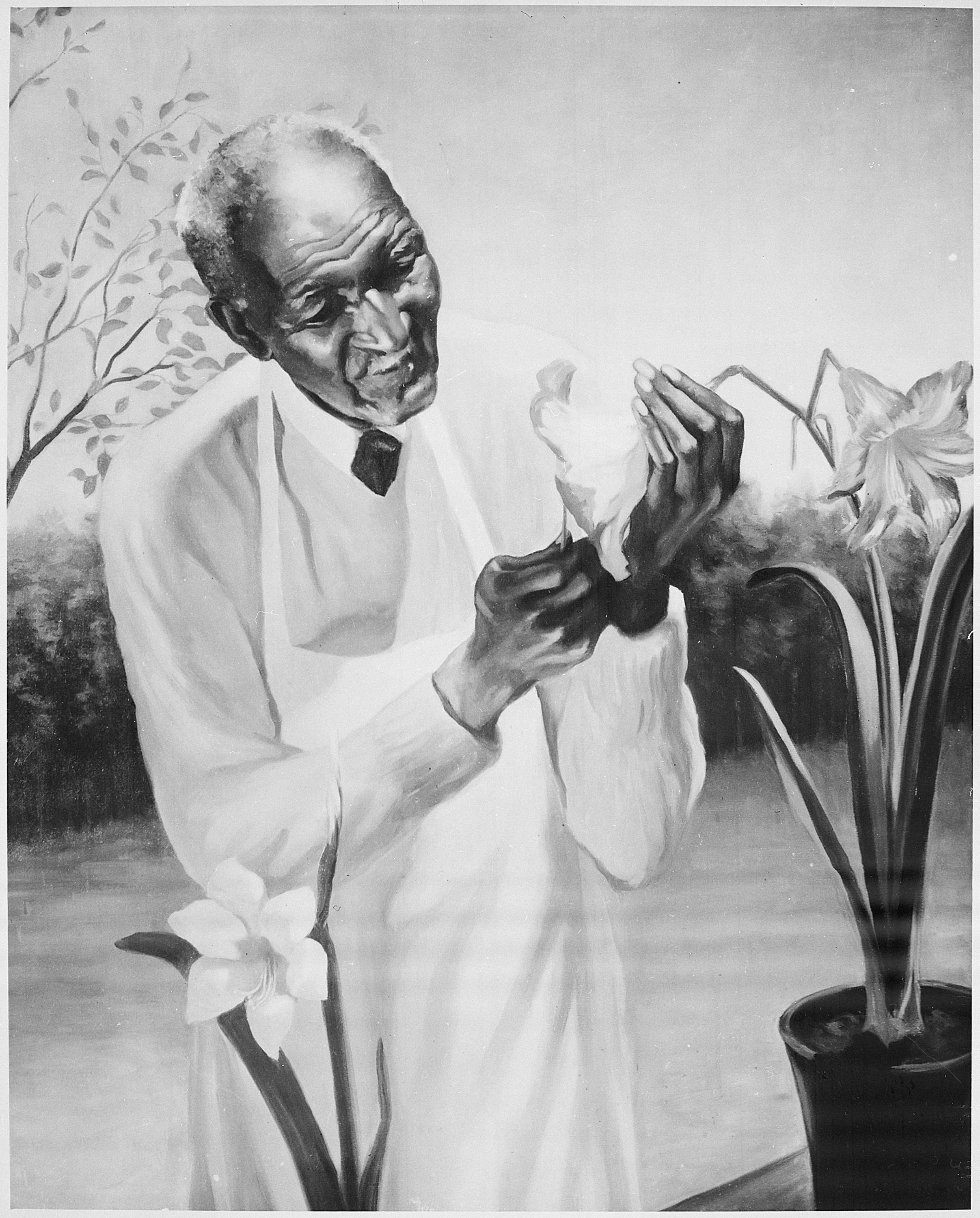

George Washington Carver ( 1864 – January 5, 1943) was an American agricultural scientist and inventor who promoted alternative crops to

Carver applied to several colleges before being accepted at Highland University in Highland, Kansas. When he arrived, they refused to let him attend because of his race. In August 1886, Carver traveled by wagon with J. F. Beeler from Highland to Eden Township in

Carver applied to several colleges before being accepted at Highland University in Highland, Kansas. When he arrived, they refused to let him attend because of his race. In August 1886, Carver traveled by wagon with J. F. Beeler from Highland to Eden Township in

from the "Blue Skyways" website of the Kansas State Library. He homesteaded a claim near Beeler, where he maintained a small conservatory of plants and flowers and a geological collection. He manually plowed of the claim, planting rice, corn, Indian corn and garden produce, as well as various fruit trees, forest trees, and shrubbery. He also earned money by odd jobs in town and worked as a ranch hand. In early 1888, Carver obtained a $300 (~$ in ) loan at the Bank of Ness City for education. By June he left the area. In 1890, Carver started studying art and piano at

Carver started his academic career as a researcher and teacher. In 1911, Washington wrote a letter to him complaining that Carver had not followed orders to plant particular crops at the experiment station. This revealed Washington's micro-management of Carver's department, which he had headed for more than 10 years by then. Washington at the same time refused Carver's requests for a new laboratory, research supplies for his exclusive use, and respite from teaching classes. Washington praised Carver's abilities in teaching and original research but said this about his administrative skills:

Carver started his academic career as a researcher and teacher. In 1911, Washington wrote a letter to him complaining that Carver had not followed orders to plant particular crops at the experiment station. This revealed Washington's micro-management of Carver's department, which he had headed for more than 10 years by then. Washington at the same time refused Carver's requests for a new laboratory, research supplies for his exclusive use, and respite from teaching classes. Washington praised Carver's abilities in teaching and original research but said this about his administrative skills:

from the

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often on the road promoting

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often on the road promoting

''George Washington Carver: The Life of the Great American Agriculturist''

, Rosen Publishing Group, 2004, pp. 90–92. Retrieved July 7, 2011. Carver had been frugal in his life, and in his seventies he established a legacy by creating a museum of his work, as well as the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee in 1938 to continue agricultural research. He donated nearly in his savings to create the foundation. Carver headed the modern organic movement in the southern agricultural system. Carver's background for his interest in organic farming sprouted from his father being killed during the Civil War, and when his mother was kidnapped by Confederate slave raiders. Now an orphan, Carver found comfort in botany when he was just 11 years old in Kansas. Carver learned about herbal medicine, natural pesticides, and natural fertilizers that yielded plentiful crops from his caretaker. When crops and house plants were dying, he would use his knowledge and go and nurse them back to health. As a teenager, he was termed the "plant doctor". When his study about infection in soybean reached Booker T. Washington, he invited him to come and teach at the Tuskegee Agricultural school. Although the emancipation allowed Black families 40 acres and a mule, President Johnson revoked this and gave the land to white plantation owners instead. This prompted Black farmers to exchange what was once their land, and in turn, a small part of the land's harvest. This led to sharecropping. Carver soon realized that farmers were not obtaining enough food to survive, and how the industrialization of cotton had contaminated the soil. Carver wanted to find a way to organically transform Alabama's failing soil. He found that alternating nitrogen-rich crops would let the soil get back to its natural state. Keeping crops like sweet potatoes, peanuts, and cowpeas would produce more food surplus and different types of food for farmers. Carver worked to pioneer organic fertilizers like swamp muck and compost for the farmers to use. These fertilizers were more sustainable to the planet and helped farmers to spend less money on fertilizers since they were recycling products. Carver pushed for woodland preservation, to help improve the quality of the topsoil. He urged farmers to feed their hogs acorns. The acorns contained natural pesticides and feeding them acorns was cheaper for the farms too. Carver's efforts towards the holistic and organic approach are still in practice today. In his research, Carver discovered Permaculture. Permaculture could be used to produce carbon from the atmosphere, produce a higher quantity of crops, and let crops flourish despite global warming.

Carver never married. At age 40, he began a courtship with Sarah L. Hunt, an elementary school teacher and the sister-in-law of Warren Logan, Treasurer of Tuskegee Institute. This lasted three years until she took a teaching job in California. In her 2015 biography, Christina Vella reviews his relationships and suggests that Carver was bisexual and constrained by mores of his historic period.

When he was 70, Carver established a friendship and research partnership with the scientist Austin W. Curtis Jr. This young black man, a graduate of

Carver never married. At age 40, he began a courtship with Sarah L. Hunt, an elementary school teacher and the sister-in-law of Warren Logan, Treasurer of Tuskegee Institute. This lasted three years until she took a teaching job in California. In her 2015 biography, Christina Vella reviews his relationships and suggests that Carver was bisexual and constrained by mores of his historic period.

When he was 70, Carver established a friendship and research partnership with the scientist Austin W. Curtis Jr. This young black man, a graduate of

from the Carver Academy website.

* 1923,

* 1923,

"George Washington Carver and the Peanut"

'' American Heritage''. 28(5): 66–73. Carver's research was intended to produce replacements from common crops for commercial products, which were generally beyond the budget of the small one-horse farmer. A misconception grew that his research on products for subsistence farmers were developed by others commercially to change Southern agriculture. Carver's work to provide small farmers with resources for more independence from the cash economy foreshadowed the "

"How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption"

, ''Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin'' 31. and has been reprinted numerous times. It provides a short overview of peanut crop production and contains a list of recipes from other agricultural bulletins, cookbooks, magazines, and newspapers, such as the ''Peerless Cookbook'', ''Good Housekeeping'', and ''Berry's Fruit Recipes''. While Carver's was not the first American agricultural bulletin devoted to peanuts,Beattie, W. R. 1911. "The Peanut". ''USDA Farmers' Bulletin'' 431. his bulletins seem to have been more popular and widespread than those that preceded his.

in JSTOR

Barry Mackintosh, "George Washington Carver and the Peanut: New Light on a Much-loved Myth"

''American Heritage'' 28(5): 66–73, 1977. * McMurry, L. O. "Carver, George Washington". ''American National Biography Online'' February 2000 * McMurry, Linda O. ''George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol'' (Oxford University Press, 1982)

online

Google copy

Guide to the George Washington Carver Letter to Dana H. Johnson.

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Finding Aid to the George Washington Carver Collection

Special Collections Department, Iowa State University Library, Ames, Iowa.

William and Annette Curtis collection of George Washington Carver items, MSS 6223

a

L. Tom Perry Special Collections

Legends of Tuskegee: George Washington Carver

from the

George Washington Carver National Monument

from the National Park Service

Carver Tribute

from

The Legacy of George Washington Carver

from

National Historic Chemical Landmark

from the

George Washington Carver Correspondence Collection

Manuscript collection in Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

Biotechnology Organization Award

*

George Washington Carver Digital Collection

Iowa State University. * *

The Boy Who Was Traded for a Horse

, a 1948 radio drama presentation from ''

"How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption"

, ''Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin'' 31. * George Washington Carver

"How the Farmer Can Save His Sweet Potatoes and Ways of Preparing Them for the Table"

''Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin'' 38, 1936. * George Washington Carver

"How to Grow the Tomato and 115 Ways to Prepare it for the Table"

''Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin'' 36, 1936. * Peter D. Burchard

"George Washington Carver: For His Time and Ours"

National Park Service: George Washington Carver National Monument. 2006. * Louis R. Harlan (ed.)

Volume 4, pp. 127–128. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. 1975. * Raleigh H. Merritt

Boston: Meador Publishing. 1929.

George Washington Carver

* Mary Bagley

(2013). {{DEFAULTSORT:Carver, George Washington * Date of birth unknown Year of birth uncertain 1860s births 1943 deaths 19th-century African-American educators 19th-century African-American scientists 19th-century American educators 19th-century American inventors 19th-century American slaves 20th-century African-American academics 20th-century African-American educators 20th-century African-American scientists 20th-century American academics 20th-century American educators 20th-century American inventors Accidental deaths from falls in the United States African American adoptees American adoptees African-American Christians African-American environmentalists American environmentalists African-American inventors Agriculture educators Alabama Republicans American agriculturalists American botanists American food scientists American mycologists Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Iowa State University alumni Iowa State University faculty People from Tuskegee, Alabama People from Indianola, Iowa People from Minneapolis, Kansas People from Ness County, Kansas People from Hanover, Massachusetts People from Newton County, Missouri Scientists from Missouri Simpson College alumni Tuskegee University faculty People enslaved in Missouri People enslaved in Kentucky

cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

and methods to prevent soil depletion. He was one of the most prominent black scientists of the early 20th century.

While a professor at Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU; formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute) is a Private university, private, Historically black colleges and universities, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It was f ...

, Carver developed techniques to improve types of soils depleted by repeated plantings of cotton. He wanted poor farmers to grow other crops, such as peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), goober pea, pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large ...

s and sweet potatoes

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant in the morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its sizeable, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable, which is a staple food in parts of the ...

, as a source of their own food and to improve their quality of life. Under his leadership, the Experiment Station at Tuskegee published over forty practical bulletins for farmers, many written by him, which included recipes; many of the bulletins contained advice for poor farmers, including combating soil depletion with limited financial means, producing bigger crops, and preserving food.

Apart from his work to improve the lives of farmers, Carver was also a leader in promoting environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

. He received numerous honors for his work, including the Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for an outstanding achievement by an African Americans, African American. The award was created in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, ...

of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

. In an era of high racial polarization, his fame reached beyond the black community. He was widely recognized and praised in the white community for his many achievements and talents. In 1941, ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine dubbed Carver a "Black Leonardo".

Early years

Carver was born intoslavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, in Diamond Grove, (now Diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

, Newton County, Missouri

Newton County is a County (United States), county located in the southwest portion of the U.S. state of Missouri. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 58,648. Its county seat is Neosho, Missouri, Neosho. The coun ...

), near Crystal Palace, sometime in the early 1860s. The date of his birth is uncertain and was not known to Carver because it was before slavery was abolished in Missouri, which occurred in January 1865, during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. His enslaver, Moses Carver, descended from a family of immigrants of German or English descent, had purchased George's parents, Mary and Giles, from William P. McGinnis on October 9, 1855, for $700 (~$ in ).

Giles died before George was born and when he was a week old, he, his sister, and his mother were kidnapped by night raiders from Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

. George's brother, James, was rushed to safety from the kidnappers. The kidnappers sold the trio in Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. Moses Carver hired John Bentley to find them, but he found only the infant George. Moses negotiated with the raiders to gain the boy's return and rewarded Bentley. After slavery was abolished, Moses Carver and his wife, Susan, raised George and his older brother, James, as their own children. They encouraged George to continue his intellectual pursuits, and "Aunt Susan" taught him the basics of reading and writing.

Black people

Black is a racial classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin and often additional phenotypical ...

were not allowed at the public school in Diamond Grove. George decided to go to a school for black children 10 miles (16 km) south, in Neosho. When he reached the town, he found the school closed for the night. He slept in a nearby barn. By his own account, the next morning he met a kind woman, Mariah Watkins, from whom he wished to rent a room. When he identified himself as "Carver's George", as he had done his whole life, she replied that from now on his name was "George Carver". George liked Mariah Watkins and her words, "You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people", made a great impression on him.

At age 13, because he wanted to attend the academy there, he moved to the home of another foster family, in Fort Scott, Kansas

Fort Scott is a city in and the county seat of Bourbon County, Kansas, Bourbon County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 7,552. It is named for Gen. Winfield Scott. The cit ...

. After witnessing the killing of a black man by a group of white people, Carver left the city. He attended a series of schools before earning his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas

Minneapolis is a city in and the county seat of Ottawa County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 1,946.

History

The community was originally called Markley's Mills, and under the latter name was l ...

.

During his time spent in Minneapolis, there was another George Carver in town, which caused confusion over receiving mail. Carver chose a middle initial at random and began requesting letters to him be addressed to George W. Carver. Someone once asked if the "W" stood for Washington, and Carver grinned and said, "Why not?" However, he never used Washington as his middle name, and signed his name as either George W. Carver or simply George Carver.

College education

Carver applied to several colleges before being accepted at Highland University in Highland, Kansas. When he arrived, they refused to let him attend because of his race. In August 1886, Carver traveled by wagon with J. F. Beeler from Highland to Eden Township in

Carver applied to several colleges before being accepted at Highland University in Highland, Kansas. When he arrived, they refused to let him attend because of his race. In August 1886, Carver traveled by wagon with J. F. Beeler from Highland to Eden Township in Ness County, Kansas

Ness County is a County (United States), county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. Its county seat and largest city is Ness City, Kansas, Ness City. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the county population was 2,687. The cou ...

.George Washington Carver: Scientist, Scholar, and Educatorfrom the "Blue Skyways" website of the Kansas State Library. He homesteaded a claim near Beeler, where he maintained a small conservatory of plants and flowers and a geological collection. He manually plowed of the claim, planting rice, corn, Indian corn and garden produce, as well as various fruit trees, forest trees, and shrubbery. He also earned money by odd jobs in town and worked as a ranch hand. In early 1888, Carver obtained a $300 (~$ in ) loan at the Bank of Ness City for education. By June he left the area. In 1890, Carver started studying art and piano at

Simpson College

Simpson College is a Private college, private United Methodist Church, Methodist college in Indianola, Iowa. It is Higher education accreditation in the United States, accredited by the Higher Learning Commission and enrolled 1,151 students in ...

in Indianola, Iowa.

His art teacher, Etta Budd, recognized Carver's talent for painting flowers and plants; she encouraged him to study botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

at Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University) in Ames.

When he began there in 1891, he was the first black student at Iowa State. Carver's bachelor's thesis for a degree in Agriculture was "Plants as Modified by Man", dated 1894. Iowa State University professors Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel convinced Carver to continue there for his master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

. Carver did research at the Iowa Experiment Station under Pammel during the next two years. His work at the experiment station in plant pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

and mycology

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungus, fungi, including their Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, genetics, biochemistry, biochemical properties, and ethnomycology, use by humans. Fungi can be a source of tinder, Edible ...

first gained him national recognition and respect as a botanist. Carver received his Master of Science degree in 1896. Carver taught as the first African American faculty member at Iowa State.

Despite occasionally being addressed as "doctor", Carver never received an official doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

, and in a personal communication with Pammel, he noted that it was a "misnomer", given to him by others due to his abilities and their assumptions about his education. Though he did not have an earned doctorate, both Simpson College and Selma University awarded him honorary doctorates of science in his lifetime. In addition, Iowa State awarded him a posthumous doctor of humane letters degree in 1994.

Tuskegee Institute

In 1896, Booker T. Washington, the first principal and president of the Tuskegee Institute (nowTuskegee University

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU; formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute) is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It was founded as a normal school for teachers on July 4, 1881, by the ...

), invited Carver to head its Agriculture Department. Carver taught there for 47 years, developing the department into a strong research center and working with two additional college presidents during his tenure. He taught methods of crop rotation, introduced several alternative cash crops for farmers that would also improve the soil of areas heavily cultivated in cotton, initiated research into crop products (chemurgy), and taught generations of black students farming techniques for self-sufficiency.

Carver designed a mobile classroom to take education out to farmers. He called it a "Jesup wagon" after the New York financier and philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

Morris Ketchum Jesup, who provided funding to support the program.

To recruit Carver to Tuskegee, Washington gave him an above average salary and two rooms for his personal use, although both concessions were resented by some other faculty. Because he had earned a master's in a scientific field from a "white" institution, some faculty perceived him as arrogant. Unmarried faculty members normally had to share rooms, with two to a room, in the spartan early days of the institute.

One of Carver's duties was to administer the Agricultural Experiment Station farms. He had to manage the production and sale of farm products to generate revenue for the institute. He soon proved to be a poor administrator and clashed with other faculty members, especially George Ruffin Bridgeforth. In 1900, Carver complained that the physical work and the letter-writing required were too much.

In 1904, an Institute committee reported that Carver's reports on yields from the poultry yard were exaggerated, and Washington confronted Carver about the issue. Carver replied in writing, "Now to be branded as a liar and party to such hellish deception it is more than I can bear, and if your committee feel that I have willfully lied or asparty to such lies as were told my resignation is at your disposal." During Washington's last five years at Tuskegee, Carver submitted or threatened his resignation several times: when the administration reorganized the agriculture programs, when he disliked a teaching assignment, to manage an experiment station elsewhere, and when he did not get summer teaching assignments in 1913–14. In each case, Washington smoothed things over.

Carver started his academic career as a researcher and teacher. In 1911, Washington wrote a letter to him complaining that Carver had not followed orders to plant particular crops at the experiment station. This revealed Washington's micro-management of Carver's department, which he had headed for more than 10 years by then. Washington at the same time refused Carver's requests for a new laboratory, research supplies for his exclusive use, and respite from teaching classes. Washington praised Carver's abilities in teaching and original research but said this about his administrative skills:

Carver started his academic career as a researcher and teacher. In 1911, Washington wrote a letter to him complaining that Carver had not followed orders to plant particular crops at the experiment station. This revealed Washington's micro-management of Carver's department, which he had headed for more than 10 years by then. Washington at the same time refused Carver's requests for a new laboratory, research supplies for his exclusive use, and respite from teaching classes. Washington praised Carver's abilities in teaching and original research but said this about his administrative skills:

When it comes to the organization of classes, the ability required to secure a properly organized and large school or section of a school, you are wanting in ability. When it comes to the matter of practical farm managing which will secure definite, practical, financial results, you are wanting again in ability.In 1911, Carver complained that his laboratory had not received the equipment which Washington had promised 11 months before. He also complained about Institute committee meetings. Washington praised Carver in his 1911 memoir, ''My Larger Education: Being Chapters from My Experience''. Washington called Carver "one of the most thoroughly scientific men of the Negro race with whom I am acquainted". After Washington died in 1915, his successor made fewer demands on Carver for administrative tasks. From 1915 to 1923, Carver concentrated on researching and experimenting with new uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, soybeans, pecans, and other crops, as well as having his assistants research and compile existing uses.Special History Study

from the

National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

website. This work, and especially his speaking to a national conference of the Peanut Growers Association in 1920 and in testimony before Congress in 1921 to support passage of a tariff on imported peanuts, brought him wide publicity and increasing renown. In these years, he became one of the most well-known African Americans of his time.

Rise to fame

Carver developed techniques to improve soils depleted by repeated plantings ofcotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

. Together with other agricultural experts, he urged farmers to restore nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

to their soils by practicing systematic crop rotation

Crop rotation is the practice of growing a series of different types of crops in the same area across a sequence of growing seasons. This practice reduces the reliance of crops on one set of nutrients, pest and weed pressure, along with the pro ...

: alternating cotton crops with plantings of sweet potatoes

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant in the morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its sizeable, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable, which is a staple food in parts of the ...

or legumes

Legumes are plants in the pea family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seeds of such plants. When used as a dry grain for human consumption, the seeds are also called pulses. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consu ...

, such as peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), goober pea, pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large ...

s, soybean

The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean (''Glycine max'') is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean. Soy is a staple crop, the world's most grown legume, and an important animal feed.

Soy is a key source o ...

s and cowpea

The cowpea (''Vigna unguiculata'') is an annual herbaceous legume from the genus '' Vigna''. Its tolerance for sandy soil and low rainfall have made it an important crop in the semiarid regions across Africa and Asia. It requires very few inpu ...

s. These crops both restored nitrogen to the soil and were good for human consumption.

Following the crop rotation practice resulted in improved cotton yields and gave farmers alternative cash crops. To train farmers to successfully rotate and cultivate the new crops, Carver developed an agricultural extension program for Alabama that was similar to the one at Iowa State. To encourage better nutrition in the South, he widely distributed recipes using the alternative crops.

He founded an industrial research laboratory, where he and assistants worked to popularize the new crops by developing hundreds of applications for them. They did original research as well as promoting applications and recipes, which they collected from others. Carver distributed his information as agricultural bulletins.

Carver's work was known by officials in the national capital before he became a public figure. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

publicly admired his work. Former professors of Carver's from Iowa State University were appointed to positions as Secretary of Agriculture: James Wilson, a former dean and professor of Carver's, served from 1897 to 1913. Henry Cantwell Wallace served from 1921 to 1924. He knew Carver personally because his son Henry A. Wallace and the researcher were friends. The younger Wallace served as U.S. Secretary of Agriculture from 1933 to 1940, and as Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's vice president from 1941 to 1945.

The American industrialist, farmer, and inventor William C. Edenborn of Winn Parish, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, grew peanuts on his demonstration farm. He consulted with Carver.

In 1916, Carver was made a member of the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

in England, one of only a handful of Americans at that time to receive this honor. Carver's promotion of peanuts gained him the most notice.

By 1920, the U.S. peanut farmers were being undercut by low prices on imported peanuts from the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

. In 1921, peanut farmers and industry representatives planned to appear at Congressional hearings to ask for a tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

. Based on the quality of Carver's presentation at their convention, they asked the African-American professor to testify on the tariff issue before the Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

. Due to segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

, it was highly unusual for an African American to appear as an expert witness, but Carver appeared and unpacked numerous exhibits and samples to make his case for greater food and industrial uses for the peanut. Southern congressmen mocked him, but as he talked about the importance of the peanut and its uses for American agriculture and manufacturing, committee members repeatedly extended the time for his testimony. The Fordney–McCumber Tariff

The Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922 was a law that raised American tariffs on many imported goods to protect factories and farms. The US Congress displayed a pro-business attitude in passing the tariff and in promoting foreign trade by providi ...

was enacted in 1922, and included a duty on imported peanuts. Carver's testimony, including samples of peanut milk, peanut flour, industrial dyes made from peanuts, and other peanut-based products, made him widely known as a public figure.

Life while famous

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often on the road promoting

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often on the road promoting Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU; formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute) is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It was founded as a normal school for teachers on July 4, 1881, by the ...

, peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), goober pea, pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large ...

s, sweet potatoes, and racial harmony. Although he only published six agricultural bulletins after 1922, he published articles in peanut industry journals and wrote a syndicated newspaper column, "Professor Carver's Advice". Business leaders came to seek his help, and he often responded with free advice. Three American presidents—Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

and Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

—met with him, and the Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

of Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

studied with him for three weeks. From 1923 to 1933, Carver toured white Southern colleges for the Commission on Interracial Cooperation.

With his increasing notability, Carver became the subject of biographies and articles. Raleigh H. Merritt contacted him for his biography published in 1929. Merritt wrote:

At present not a great deal has been done to utilize Dr. Carver's discoveries commercially. He says that he is merely scratching the surface of scientific investigations of the possibilities of the peanut and other Southern products.Raleigh Howard MerrittIn 1932, the writer James Saxon Childers wrote that Carver and his peanut products were almost solely responsible for the rise in U.S. peanut production after the boll weevil devastated the American cotton crop beginning about 1892. His article, "A Boy Who Was Traded for a Horse" (1932), in ''

''From Captivity to Fame or The Life of George Washington Carver''.

The American Magazine

''The American Magazine'' was a periodical publication founded in June 1906, a continuation of failed publications purchased a few years earlier from publishing mogul Miriam Leslie. It succeeded '' Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly'' (1876–1904) ...

'', and its 1937 reprint in ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his wi ...

'', contributed to this myth about Carver's influence. Other popular media tended to exaggerate Carver's impact on the peanut industry.

From 1933 to 1935, Carver worked to develop peanut oil massages to treat infantile paralysis (polio

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe ...

). Ultimately, researchers found that the massages, not the peanut oil, provided the benefits of maintaining some mobility to paralyzed limbs.

From 1935 to 1937, Carver participated in the USDA Disease Survey. Carver had specialized in plant diseases and mycology for his master's degree.

In 1937, Carver attended two chemurgy

Chemurgy is a branch of applied chemistry concerned with preparing industrial products from agricultural raw materials. The concept developed by the early years of the 20th century. For example, products such as brushes and motion picture film wer ...

conferences, an emerging field in the 1930s, during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

and the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of natural factors (severe drought) and hum ...

, concerned with developing new products from crops. He was invited by Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

to speak at the conference held in Dearborn, Michigan

Dearborn is a city in Wayne County, Michigan, Wayne County in the U.S. state of Michigan. An inner-ring Metro Detroit, suburb of Detroit, Dearborn borders Detroit to the south and west, roughly west of downtown Detroit. In the 2020 United States ...

, and they developed a friendship. That year Carver's health declined, and Ford later installed an elevator at the Tuskegee dormitory where Carver lived, so that the elderly man would not have to climb stairs.Linda McMurry Edwards''George Washington Carver: The Life of the Great American Agriculturist''

, Rosen Publishing Group, 2004, pp. 90–92. Retrieved July 7, 2011. Carver had been frugal in his life, and in his seventies he established a legacy by creating a museum of his work, as well as the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee in 1938 to continue agricultural research. He donated nearly in his savings to create the foundation. Carver headed the modern organic movement in the southern agricultural system. Carver's background for his interest in organic farming sprouted from his father being killed during the Civil War, and when his mother was kidnapped by Confederate slave raiders. Now an orphan, Carver found comfort in botany when he was just 11 years old in Kansas. Carver learned about herbal medicine, natural pesticides, and natural fertilizers that yielded plentiful crops from his caretaker. When crops and house plants were dying, he would use his knowledge and go and nurse them back to health. As a teenager, he was termed the "plant doctor". When his study about infection in soybean reached Booker T. Washington, he invited him to come and teach at the Tuskegee Agricultural school. Although the emancipation allowed Black families 40 acres and a mule, President Johnson revoked this and gave the land to white plantation owners instead. This prompted Black farmers to exchange what was once their land, and in turn, a small part of the land's harvest. This led to sharecropping. Carver soon realized that farmers were not obtaining enough food to survive, and how the industrialization of cotton had contaminated the soil. Carver wanted to find a way to organically transform Alabama's failing soil. He found that alternating nitrogen-rich crops would let the soil get back to its natural state. Keeping crops like sweet potatoes, peanuts, and cowpeas would produce more food surplus and different types of food for farmers. Carver worked to pioneer organic fertilizers like swamp muck and compost for the farmers to use. These fertilizers were more sustainable to the planet and helped farmers to spend less money on fertilizers since they were recycling products. Carver pushed for woodland preservation, to help improve the quality of the topsoil. He urged farmers to feed their hogs acorns. The acorns contained natural pesticides and feeding them acorns was cheaper for the farms too. Carver's efforts towards the holistic and organic approach are still in practice today. In his research, Carver discovered Permaculture. Permaculture could be used to produce carbon from the atmosphere, produce a higher quantity of crops, and let crops flourish despite global warming.

Relationships

Carver never married. At age 40, he began a courtship with Sarah L. Hunt, an elementary school teacher and the sister-in-law of Warren Logan, Treasurer of Tuskegee Institute. This lasted three years until she took a teaching job in California. In her 2015 biography, Christina Vella reviews his relationships and suggests that Carver was bisexual and constrained by mores of his historic period.

When he was 70, Carver established a friendship and research partnership with the scientist Austin W. Curtis Jr. This young black man, a graduate of

Carver never married. At age 40, he began a courtship with Sarah L. Hunt, an elementary school teacher and the sister-in-law of Warren Logan, Treasurer of Tuskegee Institute. This lasted three years until she took a teaching job in California. In her 2015 biography, Christina Vella reviews his relationships and suggests that Carver was bisexual and constrained by mores of his historic period.

When he was 70, Carver established a friendship and research partnership with the scientist Austin W. Curtis Jr. This young black man, a graduate of Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

, had some teaching experience before coming to Tuskegee. Carver bequeathed to Curtis his royalties from an authorized 1943 biography by Rackham Holt. After Carver died in 1943, Curtis was fired from Tuskegee Institute. He left Alabama and resettled in Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

. There he manufactured and sold peanut-based personal care products.

Death

Upon returning home one day, Carver suffered a bad fall down a flight of stairs; he was found unconscious by a maid who took him to a hospital. Carver died January 5, 1943, at the age of 78 or 79 from complications (anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

) resulting from this fall. His death came when he was sitting up in bed while painting a Christmas card which said, "Peace on earth and goodwill to all men." Carver biographer Prema Ramakrishnan said of him that "His death was characteristic of him and his entire life’s work." He was buried next to Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee University. Due to his frugality, Carver's life savings totaled $60,000, all of which he donated in his last years and at his death to the Carver Museum and to the George Washington Carver Foundation.

On his grave was written, "He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world."

Personal life

Christianity

Carver believed he could have faith both in God and science and integrated them into his life. He testified on many occasions that his faith inJesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

was the only mechanism by which he could effectively pursue and perform the art of science. Carver became a Christian when he was still a young boy, as he wrote in connection to his conversion in 1931:

He was not expected to live past his 21st birthday due to failing health. He lived well past the age of 21, and his belief deepened as a result. Throughout his career, he always found friendship with other Christians. He relied on them especially when criticized by the scientific community and media regarding his research methodology.

Carver viewed faith in Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

as a means of destroying both barriers of racial disharmony and social stratification. He was as concerned with his students' character development as he was with their intellectual development. He compiled a list of "eight cardinal virtues" whose possession defines "a lady or a gentleman":

* Be clean both inside and out. * Who neither looks up to the rich nor down on the poor. * Who loses, if needs be, without squealing. * Who wins without bragging. * Who is always considerate of women, children and old people. * Who is too brave to lie. * Who is too generous to cheat. * Who take his share of the world and lets other people have theirs.Beginning in 1906 at Tuskegee, Carver led a Bible class on Sundays for several students at their request. He regularly portrayed stories by acting them out.History

from the Carver Academy website.

Voice pitch

Even as an adult Carver spoke with a high pitch. Historian Linda O. McMurry noted that he "was a frail and sickly child" who suffered "from a severe case ofwhooping cough

Whooping cough ( or ), also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable Pathogenic bacteria, bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common c ...

and frequent bouts of what was called croup

Croup ( ), also known as croupy cough, is a type of respiratory infection that is usually caused by a virus. The infection leads to swelling inside the trachea, which interferes with normal breathing and produces the classic symptoms of "bar ...

". McMurry contested the diagnosis of croup, holding rather that "His stunted growth and apparently impaired vocal cords suggest instead tubercular or pneumococcal infection. Frequent infections of that nature could have caused the growth of polyps on the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ (anatomy), organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal ...

and may have resulted from a gamma globulin deficiency. ... until his death the high pitch of his voice startled all who met him, and he suffered from frequent chest congestion and loss of voice."

Honors

* 1923,

* 1923, Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for an outstanding achievement by an African Americans, African American. The award was created in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, ...

from the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, awarded annually for outstanding achievement.

* 1928, honorary doctorate from Simpson College

* 1939, the Roosevelt Medal for Outstanding Contribution to Southern Agriculture

* 1940, Carver established the George Washington Carver Foundation at the Tuskegee Institute.

* 1941, The George Washington Carver Museum was dedicated at the Tuskegee Institute.

* 1942, Ford built a replica of Carver's birth cabin at the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn as a tribute.

* 1942, Ford dedicated a laboratory in Dearborn named after Carver.

* 1943, Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Although British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost cons ...

launched

* 1947, George Washington Carver Area High School, named in his honor is opened by the Chicago Public Schools

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), officially classified as City of Chicago School District #299 for funding and districting reasons, in Chicago, Illinois, is the List of the largest school districts in the United States by enrollment, fourth-large ...

in the Riverdale/Far South Side area of Chicago, Illinois

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, United States.

* 1950, George Washington Carver State Park named

* 1951–1954, U.S. Mint features Carver on a 50 cents silver commemorative coin

* 1965, Ballistic missile submarine launched.

* 1969, Iowa State University

Iowa State University of Science and Technology (Iowa State University, Iowa State, or ISU) is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Ames, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1858 as the Iowa Agricult ...

constructs Carver Hall in honor of Carver—a graduate of the university.

* 1943?, the US Congress designated January 5, the anniversary of his death, as George Washington Carver Recognition Day.

* 1999, USDA

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that aims to meet the needs of commerc ...

names a portion of its Beltsville, Maryland, campus the George Washington Carver Center.

* 2002, Iowa Award, the state's highest citizen award.

* 2004, George Washington Carver Bridge, Des Moines, Iowa

Des Moines is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Iowa, most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is the county seat of Polk County, Iowa, Polk County with parts extending into Warren County, Iowa, Wa ...

* 2007, the Missouri Botanical Gardens has a garden area named in his honor, with a commemorative statue and material about his work

*2022, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed legislation naming Feb. 1st every year as George Washington Carver Day in Iowa

* Willowbrook Neighborhood Park in Willowbrook, California was renamed George Washington Carver Park in his honor.

* Schools named for Carver include the George Washington Carver Elementary School of the Compton Unified School District in Los Angeles County, California

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles and sometimes abbreviated as LA County, is the List of United States counties and county equivalents, most populous county in the United States, with 9,663,345 residents estimated in 202 ...

, the George Washington Carver School of Arts and Science of the Sacramento City Unified School District in Sacramento, California

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of California and the county seat, seat of Sacramento County, California, Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento Rive ...

, and the Dr. George Washington Carver Elementary School, a Newark public school in Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, the county seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County, and a principal city of the New York metropolitan area. ...

.

* Taxa named after him include: ''Colletotrichum carveri'' and ''Metasphaeria carveri'', both named by Job Bicknell Ellis and Benjamin Matlack Everhart in 1902; ''Cercospora carveriana'', named by Pier Andrea Saccardo

Pier Andrea Saccardo (23 April 1845 in Treviso, Province of Treviso, Treviso – 12 February 1920 in Padua, Italy, Padua) was an Italian botany, botanist and mycology, mycologist. His multi-volume ''Sylloge Fungorum'' was one of the first attempt ...

and Domenico Saccardo in 1906; ''Taphrina carveri'' named by Anna Eliza Jenkins in 1939; and ''Pestalotia carveri'', named by E. F. Guba in 1961.

Legacy

A movement to establish a U.S. national monument to Carver began before his death. Because ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, such non-war expenditures had been banned by presidential order. Missouri senator Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

sponsored a bill in favor of a monument. In a committee hearing on the bill, one supporter said:

The bill is not simply a momentary pause on the part of busy men engaged in the conduct of the war, to do honor to one of the truly great Americans of this country, but it is in essence a blow against theThe bill passed unanimously in both houses. On July 14, 1943, PresidentAxis An axis (: axes) may refer to: Mathematics *A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular: ** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system *** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ..., it is in essence a war measure in the sense that it will further unleash and release the energies of roughly 15,000,000 Negro people in this country for full support of our war effort.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

dedicated $30,000 (~$ in ) for the George Washington Carver National Monument west-southwest of Diamond, Missouri, the area where Carver had spent time in his childhood. This was the first national monument dedicated to an African American and the first to honor someone other than a president. The national monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure. The term may also refer to a sp ...

complex includes a bust of Carver, a -mile nature trail, a museum, the 1881 Moses Carver house, and the Carver cemetery. The national monument opened in July 1953.

In December 1947, a fire broke out in the Carver Museum, and much of the collection was damaged. ''Time'' magazine reported that all but 3 of the 48 Carver paintings at the museum were destroyed. His best-known painting, displayed at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, depicts a yucca and cactus. This canvas survived and has undergone conservation. It is displayed together with several of his other paintings.

Carver was featured on U.S. 1948 commemorative stamps. From 1951 to 1954, he was depicted on the commemorative Carver-Washington half dollar coin along with Booker T. Washington. A second stamp honoring Carver, of face value 32¢, was issued on February 3, 1998, as part of the Celebrate the Century stamp sheet series. Two ships, the Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Although British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost cons ...

SS ''George Washington Carver'' and the nuclear submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed.

Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion ...

USS ''George Washington Carver'' (SSBN-656), were named in his honor.

In 1977, Carver was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. In 1990, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a US patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also operate ...

. In 1994, Iowa State University awarded Carver a Doctor of Humane Letters. In 2000, Carver was a charter inductee in the USDA

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that aims to meet the needs of commerc ...

Hall of Heroes as the "Father of Chemurgy".

Many institutions continue to honor George Washington Carver. Dozens of elementary schools and high schools are named after him. National Basketball Association

The National Basketball Association (NBA) is a professional basketball league in North America composed of 30 teams (29 in the United States and 1 in Canada). The NBA is one of the major professional sports leagues in the United States and Ca ...

star David Robinson and his wife, Valerie, founded an academy named after Carver; it opened on September 17, 2001, in San Antonio, Texas. The Carver Community Cultural Center, a historic center located in San Antonio, is named for him.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante

Molefi Kete Asante ( ; born Arthur Lee Smith Jr.; August 14, 1942) is an American philosopher who is a leading figure in the fields of African-American studies, African studies, and communication studies. He is currently a professor in the Dep ...

listed George Washington Carver as one of 100 Greatest African Americans.

In 2005, Carver's research at the Tuskegee Institute was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all ...

. On February 15, 2005, an episode of '' Modern Marvels'' included scenes from within Iowa State University's Food Sciences Building and about Carver's work. In 2005, the Missouri Botanical Garden

The Missouri Botanical Garden is a botanical garden located at 4344 Shaw Boulevard in St. Louis, Missouri. It is also known informally as Shaw's Garden for founder and philanthropy, philanthropist Henry Shaw (philanthropist), Henry Shaw. I ...

in St. Louis, Missouri, opened a George Washington Carver garden in his honor, which includes a life-size statue of him.

A color film of Carver shot around 1937 by African American surgeon C. Allen Alexander was added to the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation (library and archival science), preservation, each selected for its cultural, historical, and aestheti ...

of the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

in 2019. The 12 minutes of footage were taken at the Tuskegee Institute, and includes Carver in his apartment, office and laboratory, as well as scenes of him tending flowers and displaying his paintings.

Reputed inventions

Carver has been given credit in popular folklore for many inventions that did not come out of his lab. Threepatents

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

(one for cosmetics; , and two for paints and stains; , and ) were issued to Carver in 1925 to 1927; however, they were not commercially successful.

Aside from these patents and some recipes for food, Carver left no records of formulae or procedures for making his products. He did not keep a laboratory notebook.

Mackintosh notes that, "Carver did not explicitly claim that he had personally discovered all the peanut attributes and uses he cited, but he said nothing to prevent his audiences from drawing the inference."Mackintosh, Barry. 1977"George Washington Carver and the Peanut"

'' American Heritage''. 28(5): 66–73. Carver's research was intended to produce replacements from common crops for commercial products, which were generally beyond the budget of the small one-horse farmer. A misconception grew that his research on products for subsistence farmers were developed by others commercially to change Southern agriculture. Carver's work to provide small farmers with resources for more independence from the cash economy foreshadowed the "

appropriate technology

Appropriate technology is a movement (and its manifestations) encompassing technology, technological choice and application that is small-scale, affordable by its users, labor-intensive, efficient energy use, energy-efficient, environmentally sust ...

" work of E. F. Schumacher

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher (16 August 1911 – 4 September 1977) was a German-born British statistician and economist who is best known for his proposals for human-scale, decentralised and appropriate technologies.Biography on the inner dust ...

.

Peanut products

Dennis Keeney, director of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture atIowa State University

Iowa State University of Science and Technology (Iowa State University, Iowa State, or ISU) is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Ames, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1858 as the Iowa Agricult ...

, wrote in the ''Leopold Letter'' (newsletter):

Carver worked on improving soils, growing crops with low inputs, and using species that fixed nitrogen (hence, the work on the cowpea and the peanut). Carver wrote in 'The Need of Scientific Agriculture in the South': "The virgin fertility of our soils and the vast amount of unskilled labor have been more of a curse than a blessing to agriculture. This exhaustive system for cultivation, the destruction of forest, the rapid and almost constant decomposition of organic matter, have made our agricultural problem one requiring more brains than of the North, East or West.Carver worked for years to create a company to market his products. The most important was the Carver Penol Company, which sold a mixture of

creosote

Creosote is a category of carbonaceous chemicals formed by the distillation of various tars and pyrolysis of plant-derived material, such as wood, or fossil fuel. They are typically used as preservatives or antiseptics.

Some creosote types w ...

and peanuts as a patent medicine

A patent medicine (sometimes called a proprietary medicine) is a non-prescription medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name, and claimed to be effective against minor disorders a ...

for respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. Sales were lackluster and the product was ineffective according to the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

. Other ventures were The Carver Products Company and the Carvoline Company. Carvoline Antiseptic Hair Dressing was a mix of peanut oil and lanolin. Carvoline Rubbing Oil was a peanut oil

Peanut oil, also known as groundnut oil or arachis oil, is a vegetable oil derived from peanuts. The oil usually has a mild or neutral flavor but, if made with roasted peanuts, has a stronger peanut flavor and aroma. It is often used in Americ ...

for massages.

Carver is often mistakenly credited with the invention of peanut butter

Peanut butter is a food Paste (food), paste or Spread (food), spread made from Grinding (abrasive cutting), ground, dry roasting, dry-roasted peanuts. It commonly contains additional ingredients that modify the taste or texture, such as salt, ...

. By the time Carver published "How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it For Human Consumption" in 1916, many methods of preparation of peanut butter had been developed or patented by various pharmacists, doctors and food scientists working in the US and Canada. The Aztecs

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the ...

were known to have made peanut butter from ground peanuts as early as the 15th century. Canadian pharmacist Marcellus Gilmore Edson was awarded (for its manufacture) in 1884, 12 years before Carver began his work at Tuskegee.

Sweet potato products

Carver is also associated with developingsweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant in the morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its sizeable, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable, which is a staple food in parts of ...

products. In his 1922 sweet potato bulletin, Carver listed a few dozen recipes, "many of which I have copied verbatim from Bulletin No. 129, U. S. Department of Agriculture". Carver's records included the following sweet potato products: 73 dyes, 17 wood fillers, 14 candies, 5 library pastes, 5 breakfast foods, 4 starches, 4 flours, and 3 molasses. He also had listings for vinegars, dry coffee and instant coffee, candy, after-dinner mints, orange drops, and lemon drops.

Carver bulletins

During his more than four decades at Tuskegee, Carver's official published work consisted mainly of 44 practical bulletins for farmers. His first bulletin in 1898 was on feeding acorns to farm animals. His final bulletin in 1943 was about the peanut. He also published six bulletins on sweet potatoes, five on cotton, and four on cowpeas. Some other individual bulletins dealt with alfalfa, wild plum, tomato, ornamental plants, corn, poultry, dairying, hogs, preserving meats in hot weather, and nature study in schools. His most popular bulletin, ''How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption'', was first published in 1916Carver, George Washington. 1916"How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption"

, ''Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin'' 31. and has been reprinted numerous times. It provides a short overview of peanut crop production and contains a list of recipes from other agricultural bulletins, cookbooks, magazines, and newspapers, such as the ''Peerless Cookbook'', ''Good Housekeeping'', and ''Berry's Fruit Recipes''. While Carver's was not the first American agricultural bulletin devoted to peanuts,Beattie, W. R. 1911. "The Peanut". ''USDA Farmers' Bulletin'' 431. his bulletins seem to have been more popular and widespread than those that preceded his.

See also

*African-American history

African-American history started with the forced transportation of List of ethnic groups of Africa, Africans to North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. The European colonization of the Americas, and the resulting Atlantic slave trade, ...

* Black homesteaders

* Carver College

* Carver Academy, Texas

* Carver Court, a historic housing development in Chester County, Pennsylvania

* George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology, a public high school in Towson, Maryland

* Carver High School (disambiguation)

* Carver Junior College, Cocoa, Florida, closed in 1963

* Carver Middle School (disambiguation)

* List of people on stamps of the United States

Citations

General references

Scholarly studies

* Hersey, Mark D. ''My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver'' (University of Georgia Press; 2011) 306 pages. * Hersey, Mark. "Hints and Suggestions to Farmers: George Washington Carver and Rural Conservation in the South". ''Environmental History'' 11#2 (2006): 239–268. * Mackintosh, Barry. "George Washington Carver: The Making of a Myth". ''Journal of Southern History'' 42#4 (1976): 507–528in JSTOR

Barry Mackintosh, "George Washington Carver and the Peanut: New Light on a Much-loved Myth"

''American Heritage'' 28(5): 66–73, 1977. * McMurry, L. O. "Carver, George Washington". ''American National Biography Online'' February 2000 * McMurry, Linda O. ''George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol'' (Oxford University Press, 1982)

online

Google copy

Popular works

* Carver, George Washington. "1897 or Thereabouts: George Washington Carver's Own Brief History of His Life". George Washington Carver National Monument. * Collins, David R. ''George Washington Carver: Man's Slave, God's Scientist'', (Mott Media, 1981) * William J. Federer, ''George Washington Carver: His Life & Faith in His Own Words'', AmeriSearch (2003) * Kremer, G. R. ed. ''George Washington Carver: In His Own Words'', University of Missouri Press; 1987, Reprint edition (1991) * H. M. Morris, ''Men of Science, Men of God'' (1982) * E. C. Barnett and D. Fisher, ''Scientists Who Believe'' (1984)Further reading

* Gray, James Marion. ''George Washington Carver''. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991. * Holt, Rackham. ''George Washington Carver: An American Biography'', rev. ed. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963. * Kremer, Gary R. ''Race and Meaning: The African American Experience in Missouri'', University of Missouri Press, 2014. * McKissack, Pat, and Fredrick McKissack. ''George Washington Carver: The Peanut Scientist'', rev. ed. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, 2002. * Moore, Eva. ''The Story of George Washington Carver'', New York: Scholastic, 1995. * Vella, Christina. ''Carver'', Louisiana State University Press, 2015.External links

Archival collectionsGuide to the George Washington Carver Letter to Dana H. Johnson.

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Finding Aid to the George Washington Carver Collection

Special Collections Department, Iowa State University Library, Ames, Iowa.

William and Annette Curtis collection of George Washington Carver items, MSS 6223

a

L. Tom Perry Special Collections

Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU) is a Private education, private research university in Provo, Utah, United States. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is the flagship university of the Church Educational System sponsore ...

Other

* National Park Service