Genocide Of Native Americans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The destruction of Native American peoples, cultures, and languages has been characterized as

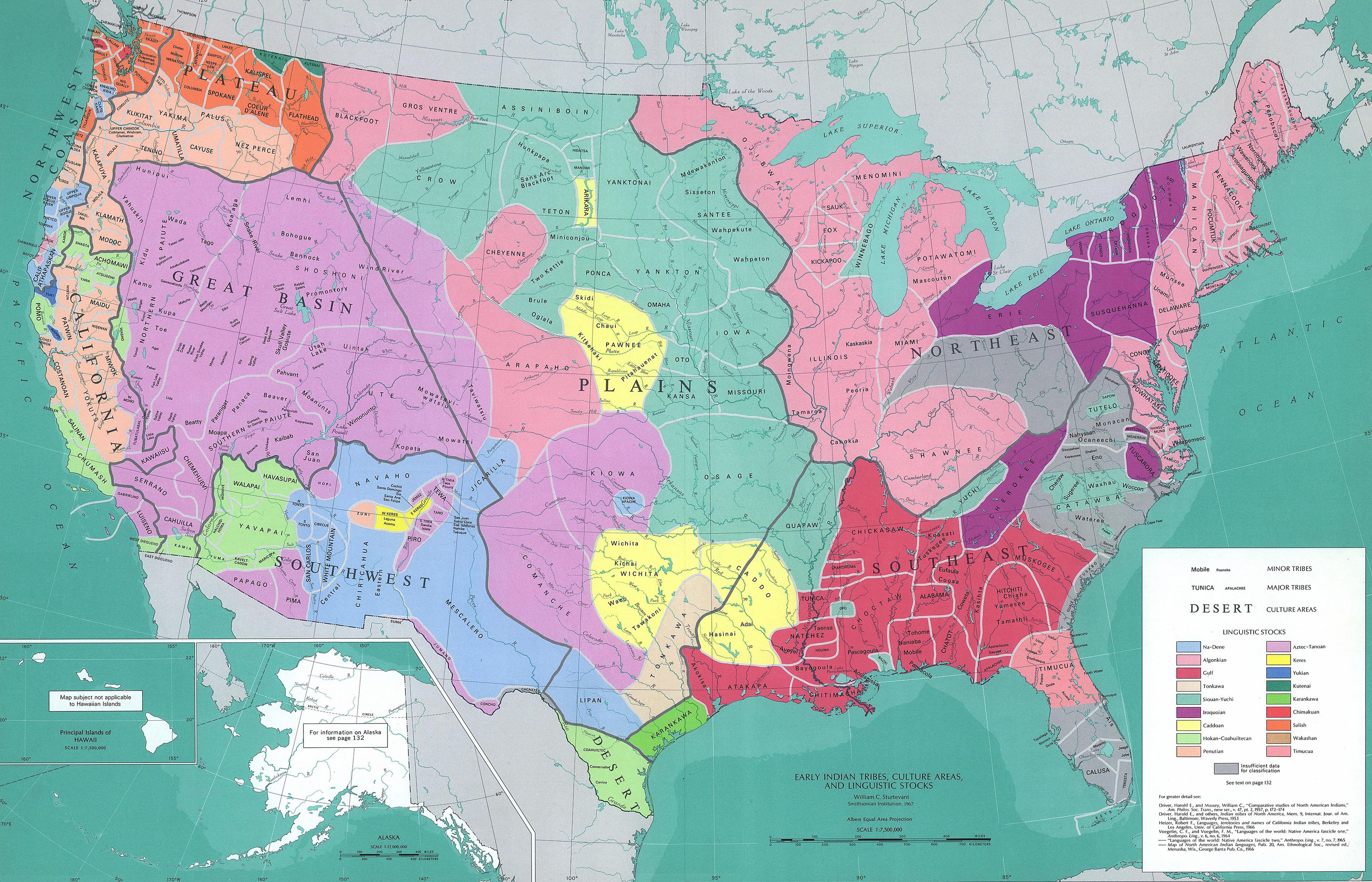

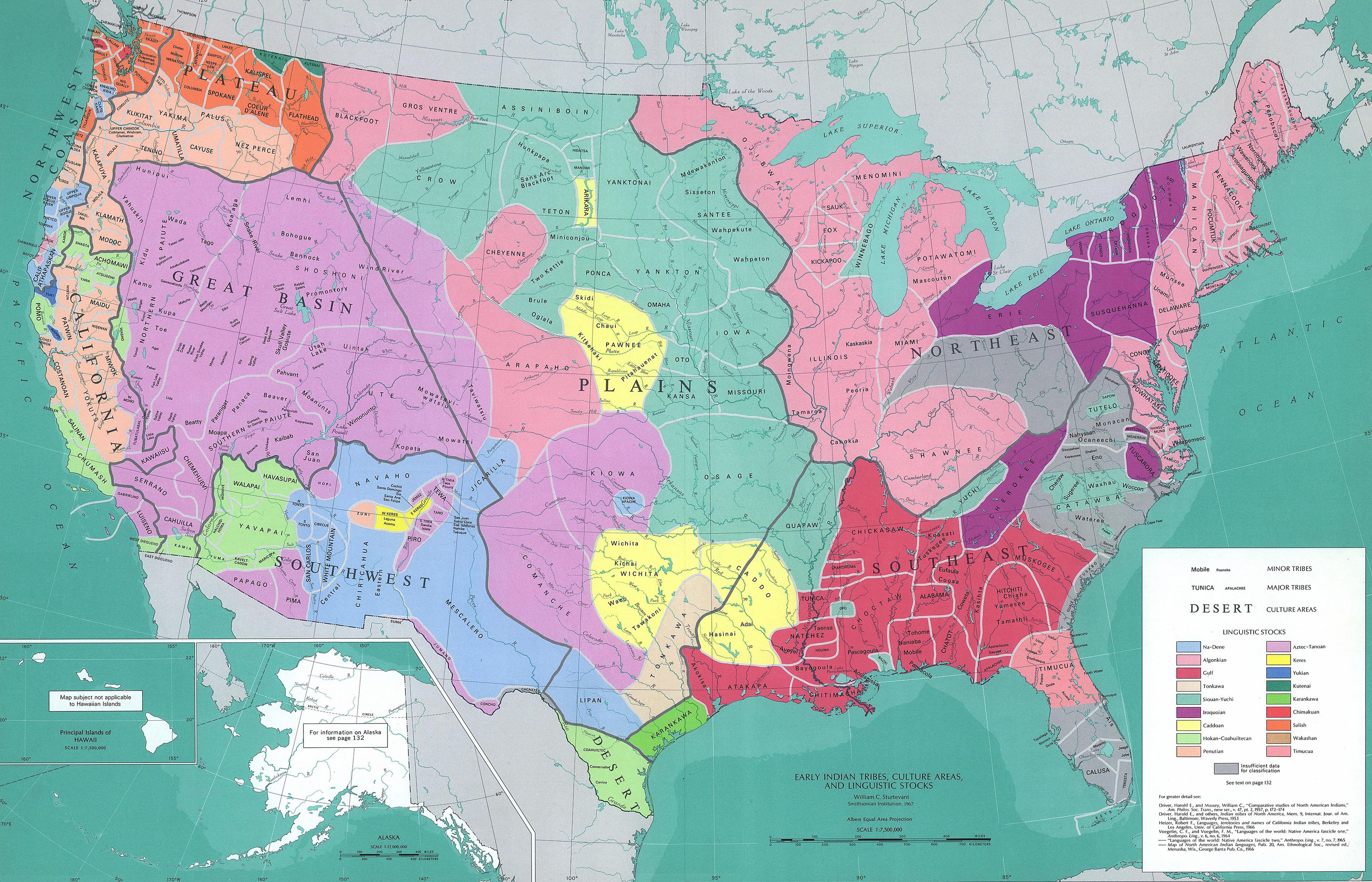

Population estimates for the pre-Columbian U.S. territory generally range from between 1 and 5 million people. Prominent cultures in the historical period before colonization included: Adena, Old Copper,

Population estimates for the pre-Columbian U.S. territory generally range from between 1 and 5 million people. Prominent cultures in the historical period before colonization included: Adena, Old Copper,

, ''New Georgia Encyclopedia'', 2002, accessed November 15, 2009 It was composed of a series of urban settlements and

On June 12, 1755, during the

On June 12, 1755, during the

The

The

The

The

Indian removal policies led to the current day reservation system which allocated territories to individual tribes. According to scholar

Indian removal policies led to the current day reservation system which allocated territories to individual tribes. According to scholar

In reference to colonialism in the United States,

In reference to colonialism in the United States,

The Native American boarding school system was a 150-year program and federal policy that separated Indigenous children from their families and sought to assimilate them into white society. It began in the early 19th century, coinciding with the start of Indian Removal policies. A Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report was published on May 11, 2022, which officially acknowledged the federal government's role in creating and perpetuating this system. According to the report, the U.S. federal government operated or funded more than 408 boarding institutions in 37 states between 1819 and 1969. 431 boarding schools were identified in total, many of which were run by religious institutions.

The report described the system as part of a federal policy aimed at eradicating the identity of Indigenous communities and confiscating their lands. Abuse was widespread at the schools, as was overcrowding, malnutrition, disease and lack of adequate healthcare, all of which worsened the effect of disease. The report documented over 500 child deaths at 19 schools, although it is estimated the total number could rise to thousands, and possibly even tens of thousands.

Marked or unmarked burial sites were discovered at 53 schools. The school system has been described as a cultural genocide and a racist

The Native American boarding school system was a 150-year program and federal policy that separated Indigenous children from their families and sought to assimilate them into white society. It began in the early 19th century, coinciding with the start of Indian Removal policies. A Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report was published on May 11, 2022, which officially acknowledged the federal government's role in creating and perpetuating this system. According to the report, the U.S. federal government operated or funded more than 408 boarding institutions in 37 states between 1819 and 1969. 431 boarding schools were identified in total, many of which were run by religious institutions.

The report described the system as part of a federal policy aimed at eradicating the identity of Indigenous communities and confiscating their lands. Abuse was widespread at the schools, as was overcrowding, malnutrition, disease and lack of adequate healthcare, all of which worsened the effect of disease. The report documented over 500 child deaths at 19 schools, although it is estimated the total number could rise to thousands, and possibly even tens of thousands.

Marked or unmarked burial sites were discovered at 53 schools. The school system has been described as a cultural genocide and a racist

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

. Debates are ongoing as to whether the entire process or only specific periods or events meet the definitions of genocide. Many of these definitions focus on intent, while others focus on outcomes. Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin (; 24 June 1900 – 28 August 1959) was a Polish lawyer who is known for coining the term "genocide" and for campaigning to establish the Genocide Convention, which legally defines the act. Following the German invasion of Poland ...

, who coined the term "genocide", considered the displacement of Native Americans by European settlers as a historical example of genocide. Others, like historian Gary Anderson, contend that genocide does not accurately characterize any aspect of American history, suggesting instead that ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

is a more appropriate term.

Historians have long debated the pre-European population of the Americas. In 2023, historian Ned Blackhawk

Ned Blackhawk (b. ca. 1971) is an enrolled member of the Te-Moak tribe of the Western Shoshone and a historian currently on the faculty of Yale University. In 2007 he received the Frederick Jackson Turner Award for his first major book, ''Viole ...

suggested that Northern America's population (Including modern-day Canada and the United States) had halved from 1492 to 1776 from about 8 million people (all Native American in 1492) to under 4 million (predominantly white in 1776). Russell Thornton

Russell Thornton (born 20 February 1942) is a Cherokee- American anthropologist and professor of anthropology at the University of California at Los Angeles, who is known for his studies of the population history of the Indigenous peoples of the A ...

estimated that by 1800, some 600,000 Native Americans lived in the regions that would become the modern United States and declined to an estimated 250,000 by 1890 before rebounding.

The virgin soil thesis (VST), coined by historian Alfred W. Crosby

Alfred Worcester Crosby Jr. (January 15, 1931 – March 14, 2018) was a professor of History, Geography, and American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and University of Helsinki. He was the author of books including '' The Columbian ...

, proposes that the population decline among Native Americans after 1492 is due to Native populations being immunologically unprepared for Old World diseases. While this theory received support in popular imagination and academia for years, recently, scholars such as historians Tai S. Edwards and Paul Kelton argue that Native Americans "'died because U.S. colonization, removal policies, reservation confinement, and assimilation programs severely and continuously undermined physical and spiritual health. Disease was the secondary killer.'" According to these scholars, certain Native populations did not necessarily plummet after initial contact with Europeans, but only after violent interactions with colonizers, and at times such violence and colonial removal exacerbated disease's effects.

The population decline among Native Americans after 1492 is attributed to various factors, mostly Eurasian diseases like influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

, pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague is a severe lung infection caused by the bacterium '' Yersinia pestis''. Symptoms include fever, headache, shortness of breath, chest pain, and coughing. They typically start about three to seven days after exposure. It is o ...

s, cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

. Additionally, conflicts, massacres, forced removal, enslavement, imprisonment, and warfare with European settlers contributed to the reduction in populations and the disruption of traditional societies. Historian Jeffrey Ostler emphasizes the importance of considering the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonization of the Americas, European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States o ...

, campaigns by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

to subdue Native American nations in the American West starting in the 1860s, as genocide. Scholars increasingly refer to these events as massacre

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians Glossary of French words and expressions in English#En masse, en masse by an armed ...

s or "genocidal massacres", defined as the annihilation of a portion of a larger group, sometimes intended to send a message to the larger group.

Native American peoples have been subject to both historical and contemporary massacres

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

and acts of cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or culturicide is a concept first described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944, in the same book that coined the term ''genocide''. The destruction of culture was a central component in Lemkin's formulation of genocide ...

as their traditional ways of life were threatened by settlers. Colonial massacres and acts of ethnic cleansing explicitly sought to reduce Native populations and confine them to reservations. Cultural genocide was also deployed, in the form of displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and physics

*Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

and appropriation of Indigenous knowledge, to weaken Native sovereignty. Native American peoples still face challenges stemming from colonialism, including settler occupation of their traditional homelands, police brutality, hate crimes, vulnerability to climate change, and mental health issues. Despite this, Native American resistance to colonialism and genocide has persisted both in the past and the present.

Background

Population estimates for the pre-Columbian U.S. territory generally range from between 1 and 5 million people. Prominent cultures in the historical period before colonization included: Adena, Old Copper,

Population estimates for the pre-Columbian U.S. territory generally range from between 1 and 5 million people. Prominent cultures in the historical period before colonization included: Adena, Old Copper, Oasisamerica

Oasisamerica is a cultural region of Indigenous peoples in North America. Their precontact cultures were predominantly agrarian, in contrast with neighboring tribes to the south in Aridoamerica. The region spans parts of Northwestern Mexico an ...

, Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

, Fort Ancient

The Fort Ancient culture is a Native American archaeological culture that dates back to . Members of the culture lived along the Ohio River valley, in an area running from modern-day Ohio and western West Virginia through to northern Kentucky ...

, Hopewell tradition

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 1 ...

and Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

s.

In the classification of the archaeology of the Americas

The archaeology of the Americas is the study of the archaeology of the Western Hemisphere, including North America (Mesoamerica), Central America, South America and the Caribbean. This includes the study of pre-historic/pre-Columbian and historic ...

, the post-Classic stage

In the classification of the archaeology of the Americas, the Post-Classic stage is a term applied to some Pre-Columbian era, pre-Columbian cultures, typically ending with local contact with Europeans. This stage is the fifth of five Archaeology, ...

is a term applied to some Precolumbian cultures, typically ending with local contact with Europeans. This stage is the fifth of five archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

stages posited by Gordon Willey

Gordon Randolph Willey (7 March 1913 – 28 April 2002) was an American archaeologist who was described by colleagues as the "dean" of New World archaeology.Sabloff 2004, p.406 Willey performed fieldwork at excavations in South America, Central A ...

and Philip Phillips' 1958 book ''Method and Theory in American Archaeology''. In the North American chronology, the "post-classic stage" followed the classic stage

In archaeological cultures of North America, the classic stage is the theoretical North and Meso-American societies that existed between AD 500 and 1200. This stage is the fourth of five stages posited by Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips' 195 ...

in certain areas, and typically dates from around AD 1200 to modern times.

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast are composed of many nations and tribal affiliations, each with distinctive cultural and political identities. They share certain beliefs, traditions and prac ...

were of many nations and tribal affiliations, each with distinctive cultural and political identities, but they shared certain beliefs, traditions, and practices, such as the centrality of salmon

Salmon (; : salmon) are any of several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the genera ''Salmo'' and ''Oncorhynchus'' of the family (biology), family Salmonidae, native ...

as a resource and spiritual symbol. Their gift-giving feast, potlatch

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States,Harkin, Michael E., 2001, Potlatch in Anthropology, International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Scienc ...

, is a highly complex event where people gather to commemorate special events. These events include the raising of a totem pole

Totem poles () are monumental carvings found in western Canada and the northwestern United States. They are a type of Northwest Coast art, consisting of poles, posts or pillars, carved with symbols or figures. They are usually made from large t ...

or the appointment or election of a new chief. The most famous artistic feature of the culture is the totem pole, with carvings of animals and other characters to commemorate cultural beliefs, legends, and notable events.

The Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

was a mound-building Native American civilization archaeologists date from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally.Adam King, "Mississippian Period: Overview", ''New Georgia Encyclopedia'', 2002, accessed November 15, 2009 It was composed of a series of urban settlements and

satellite village

A satellite village is a term for one or more settlements that have arisen within the outskirts of a larger one. Normally people would live in a satellite village, while they worked in the city.

See also

* Satellite city

A satellite city ...

s (suburbs) linked together by a loose trading network, the largest city being Cahokia

Cahokia Mounds ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from present-day St. Louis. The state archaeology park lies in south-western Illinois between East St. L ...

, believed to be a major religious center. The civilization flourished in what is now the Midwestern

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

, Eastern, and Southeastern United States.

Numerous pre-Columbian societies were urbanized, such as the Pueblo peoples

The Pueblo peoples are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Among the currently inhabited Pueblos, Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi are some of the ...

, Mandan

The Mandan () are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still ...

, and Hidatsa

The Hidatsa ( ) are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a pa ...

. The Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

League of Nations or "People of the Long House" was a politically advanced, democratic society, which is thought by some historians to have influenced the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

, with the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

passing a resolution to this effect in 1988. Other historians have contested this interpretation and believe the impact was minimal, or did not exist, pointing to numerous differences between the two systems and the ample precedents for the constitution in European political thought.

Many Indigenous nations shared the belief of collective continuance and systems of responsibility with other humans and the non-human world. According to Citizen Potawatomi

The Potawatomi (), also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains, upper Mississippi River, and western Great Lakes region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, ...

philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte

Kyle Powys Whyte is an Indigenous philosopher and climate/environmental justice scholar. He is a Professor of Environment and Sustainability and George Willis Pack Professor at the University of Michigan's School for Environment and Sustainability ...

, collective continuance refers to a society's ability to adapt to conditions to ensure community survival. Collective continuance begets the creation of systems of responsibility, in which individuals have a moral reciprocal relationship with the non-human world. The Oceti Sakowin

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin ( ; Dakota/Lakota: ) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples (translatio ...

belief of Mni Wiconi (water is life), for instance, describes a relationship in which the Missouri River nourishes their community, and they have a responsibility to protect it. The idea of collective continuance and systems of responsibility also extend into social structures. For example, for the Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabe (alternatively spelled Anishinabe, Anicinape, Nishnaabe, Neshnabé, Anishinaabeg, Anishinabek, Aanishnaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region of C ...

, gender was not binary, and women had more leadership roles that included responsibilities to others beyond their marriages.

Colonial massacres

Attempted extermination of the Pequot

The Pequot War was an armed conflict that took place between 1636 and 1638 in New England between thePequot

The Pequot ( ) are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut includin ...

tribe and an alliance of the colonists

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among the first settli ...

of the Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its northern and sout ...

, Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Narragansett and Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Indigenous people originally based in what is now southeastern Connecticut in the United States. They are part of the Eastern Algonquian linguistic and cultural family and historically shared close ties with the neighboring ...

tribes.

The war concluded with the decisive defeat of the Pequots. The colonies of Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

and Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

offered bounties for the heads of killed hostile Indians, and later for just their scalps, during the Pequot War

The Pequot War was an armed conflict that took place in 1636 and ended in 1638 in New England, between the Pequot nation and an alliance of the colonists from the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Na ...

in the 1630s; Connecticut specifically reimbursed Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Indigenous people originally based in what is now southeastern Connecticut in the United States. They are part of the Eastern Algonquian linguistic and cultural family and historically shared close ties with the neighboring ...

s for slaying the Pequot

The Pequot ( ) are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut includin ...

in 1637. At the end, about 700 Pequots had been killed or taken into captivity.

The English colonists imposed a harshly punitive treaty on the estimated 2,500 Pequots who survived the war; the Treaty of Hartford of 1638 sought to eradicate the Pequot cultural identity—with terms prohibiting the Pequots from returning to their lands, speaking their tribal language, or even referring to themselves as Pequots—and effectively dissolved the Pequot Nation, with many survivors executed or enslaved and sold away. Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to the West Indies; other survivors were dispersed as captives to the victorious tribes. The result was the elimination of the Pequot tribe as a viable polity in Southern New England, the colonial authorities classifying them as extinct. However, members of the Pequot tribe still live today as a federally recognized tribe.

Massacre of the Narragansett people

The Great Swamp Massacre was committed duringKing Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1678 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodland ...

by colonial militia of New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

on the Narragansett people

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The tribe was nearly l ...

in December 1675. On December 15 of that year, Narraganset warriors attacked the Jireh Bull Blockhouse and killed at least 15 people. Four days later, the militias from the English colonies of Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

, and Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its northern and sout ...

were led to the main Narragansett town in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The settlement was burned, its inhabitants (including women and children) killed or evicted, and most of the tribe's winter stores destroyed. It is believed that at least 97 Narragansett warriors and 300 to 1,000 non-combatants were killed, though exact figures are unknown.Gott, Richard (2004). ''Cuba: A new history''. Yale University Press. p. 32. The massacre was a critical blow to the Narragansett tribe during the period directly following the massacre. However, much like the Pequot, the Narragansett people continue to live today as a federally recognized tribe.

French and Indian War and Pontiac's War

On June 12, 1755, during the

On June 12, 1755, during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

, Massachusetts governor William Shirley

William Shirley (2 December 1694 – 24 March 1771) was a British colonial administrator who served as the governor of the British American colonies of Massachusetts Bay and the Bahamas. He is best known for his role in organizing the succ ...

issued a bounty of £40 for a male Indian scalp, and £20 for scalps of Indian females or of children under 12 years old. In 1756, Pennsylvania lieutenant-governor Robert Hunter Morris, in his declaration of war against the Lenni Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historical territory included present-day northeastern Del ...

(Delaware) people, offered "130 Pieces of Eight, for the Scalp of Every Male Indian Enemy, above the Age of Twelve Years", and "50 Pieces of Eight for the Scalp of Every Indian Woman, produced as evidence of their being killed." During Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a confederation of Native Americans who were dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754– ...

, Colonel Henry Bouquet conspired with his superior, Sir Jeffrey Amherst, to infect hostile Native Americans through biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or Pathogen, infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and Fungus, fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an ...

with smallpox blankets.

Ethnic cleansing

Sullivan Expedition

Near the beginning of the Revolutionary War, the British Army and Native American allies staged attacks on frontier towns in the Mohawk Valley region of New York. To resolve this issue, George Washington ordered theContinental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

, under the command of John Sullivan and James Clinton

Major general (United States), Major-General James Clinton (August 9, 1736 – September 22, 1812) was a Continental Army officer and politician who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

During the war he, along with John Sullivan (ge ...

, to conduct a series of scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

campaigns against the four British-allied nations of the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

. Washington's orders followed an initial assault against the Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

where Colonel Van Schaik burned two Onondaga villages. In May 1779, Washington wrote, "The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more."

Sullivan and Clinton's troops reportedly burned over forty settlements and hundreds of acres of crops, as well as an estimated 160,000 bushels of corn. Despite this, Sullivan failed to capture a sizable number of prisoners, and did not achieve the original goal of invading the British base at Fort Niagara. The Continental Army also failed to completely dispel threats from the Haudenosaunee. In fact, attacks against frontier towns increased after the expedition, as the Haudenosaunee pursued revenge. Historian Joseph R. Fischer has called the expedition a "well-executed failure." Although the expedition's goal of eliminating Native populations was not met, the Haudenosaunee still faced hardship as many lost their livelihoods and were displaced from their homes.

The Sullivan Expedition has been memorialized by American settlers in what historical anthropologist A. Lynn Smith calls the "Sullivan commemorative complex." Smith refers to monuments, markers, and places bearing the name of the expedition as a celebration of colonialism and domination, and she argues that they affect how local residents relate to their past. Smith shows that Haudenosaunee populations are harmed by this commemorative complex that pinpoints the sites of destruction on their ancestral lands and seeks to replace Native memory. Many people, both Native and non-Native, disapprove of these commemorative markers, and various activists and organizations seek to get markers removed and reveal the reality of the Expedition.

Manifest destiny

Manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

had serious consequences for Native Americans, since continental expansion implicitly meant the occupation and annexation of Native American land, sometimes to expand slavery. This ultimately led to confrontations and wars with several groups of native peoples via Indian removal. The United States continued the European practice of recognizing only limited land rights of Indigenous peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

. In a policy formulated largely by Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

in the Washington administration, the U.S. government sought to expand into the west through the purchase of Native American land in treaties.

The United States justified manifest destiny with the Doctrine of Discovery

The discovery doctrine, or doctrine of discovery, is a disputed interpretation of international law during the Age of Discovery, introduced into United States municipal law by the US Supreme Court Justice John Marshall in '' Johnson v. McIntos ...

, a fifteenth century international law developed by the Catholic Church. Three landmark Supreme Court cases, the Marshall Trilogy, invoked the Doctrine of Discovery to declare that Native Americans were domestic dependent Nations and only had limited sovereignty on their own land.

Only the federal government could purchase Indian lands, and this was done through treaties with tribal leaders. Whether a tribe actually had a decision-making structure capable of making a treaty was a controversial issue. The national policy was for the Indians to join American society and become "civilized", which meant no more wars with neighboring tribes or raids on white settlers or travelers, and a shift from hunting to farming and ranching. Advocates of civilization programs believed that the process of settling native tribes would greatly reduce the amount of land needed by the Native Americans, making more land available for homesteading by white Americans. Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

believed that the Indigenous people of America had to assimilate and live like the whites or inevitably be pushed aside by them. Once Jefferson believed that assimilation was no longer possible, he advocated for the extermination or displacement of Indigenous people. Following the forced removal of many Indigenous peoples, Americans increasingly believed that Native American ways of life would eventually disappear as the United States expanded. Humanitarian advocates of removal believed that American Indians would be better off moving away from whites.

As historian Reginald Horsman argued in his influential study ''Race and Manifest Destiny'', racial rhetoric increased during the era of manifest destiny. Americans increasingly believed that Native American ways of life would "fade away" as the United States expanded. As an example, this idea was reflected in the work of one of America's first great historians, Francis Parkman, whose landmark book ''The Conspiracy of Pontiac'' was published in 1851. Parkman wrote that after the French defeat in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

, Indians were "destined to melt and vanish before the advancing waves of Anglo-American power, which now rolled westward unchecked and unopposed". Parkman emphasized that the collapse of Indian power in the late 18th century had been swift and was a past event.

While some literary works, like those of James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonial and indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

, portrayed Native Americans positively, others did not: Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

, for example, was overwhelmingly negative in his characterizations, and seeking to counter the trope of the "Noble Aborigine" in 1870 went so far as to write that the "Noble Red Man" was " ..nothing but a poor filthy, naked scurvy vagabond, whom to exterminate were a charity to the Creator's worthier insects and reptiles which he oppresses".

Trail of Tears

The

The Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

was an ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

and forced displacement

Forced displacement (also forced migration or forced relocation) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of perse ...

of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Cr ...

" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

, Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek or just Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language; English: ), are a group of related Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands Here they waged war again ...

(Creek), Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is ...

, and Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the Southeastern United States to newly designated Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

after the passage of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

in 1830. The Cherokee removal

The Cherokee removal (May 25, 18381839), part of the Indian removal, refers to the forced displacement of an estimated 15,500 Cherokees and 1,500 African-American slaves from the U.S. states of Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Alabama to ...

in 1838 (the last forced removal east of the Mississippi) was brought on by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia

Dahlonega ( ) is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at t ...

, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush was the second significant gold rush in the United States and the first in Georgia, and overshadowed the previous rush in North Carolina. It started in 1829 in present-day Lumpkin County near the county seat, Dahlonega, ...

. The relocated peoples suffered from exposure, disease, and starvation while en route to their newly designated Indian reserve. Thousands, made vulnerable by removal, died from disease before reaching their destinations or shortly after. Some historians have said that the event constituted a genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

, although this label remains a matter of debate.

Chalk and Jonassohn assert that the deportation of the Cherokee tribe along the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

would almost certainly be considered an act of genocide today. The Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

of 1830 led to the exodus. About 17,000 Cherokees, along with approximately 2,000 Cherokee-owned black slaves, were removed from their homes. Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of a known cholera epidemic, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, following the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

signed into law by President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

in 1830, 8,000 Cherokee died, about half the total population.

Indiana

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, several Native American groups such as thePotawatomi

The Potawatomi (), also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains, upper Mississippi River, and western Great Lakes region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, ...

and Miami

Miami is a East Coast of the United States, coastal city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County in South Florida. It is the core of the Miami metropolitan area, which, with a populat ...

were expelled from their homelands in Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

under the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

. The Potawatomi Trail of Death

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced Indian Removal, removal by militia in 1838 of about 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers ...

alone led to the deaths of over 40 individuals.McKee, "The Centennial of 'The Trail of Death'," p. 36.

Long Walk

The

The Long Walk of the Navajo

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo (), was the deportation and ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government and the United States A ...

, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo (), was the 1864 deportation and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

of the Navajo people

The Navajo or Diné are an Native Americans in the United States, Indigenous people of the Southwestern United States. Their traditional language is Navajo language, Diné bizaad, a Southern Athabascan language.

The states with the largest Din ...

by the United States federal government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

. Navajos were forced to walk from their land in western New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomi ...

(modern-day Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

) to Bosque Redondo

Fort Sumner was a military fort in New Mexico Territory charged with the internment of Navajo and Mescalero Apache populations from 1863 to 1868 at nearby Bosque Redondo.

History

On October 31, 1862, Congress authorized the construction of ...

in eastern New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

. Some 53 different forced marches occurred between August 1864 and the end of 1866. Some anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

s claim that the "collective trauma of the Long Walk scritical to contemporary Navajos' sense of identity as a people".

Yavapai Exodus

In 1886, many of the Yavapai ethnic group joined in campaigns by the US Army, as scouts, againstGeronimo

Gerónimo (, ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a military leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache bands the Tchihen ...

and other Chiricahua Apache. The wars ended with the Yavapai's and the Tonto's removal from the Camp Verde Reservation to San Carlos on February 27, 1875, now known as Exodus Day. 1,400 where relocated in these travels and over the course the relocation the Yavapai received no wagons or rest stops. Yavapai were beaten with whips through rivers of melted snow in which many drowned, any Yavapai who lagged behind was left behind or shot. The march lead to 375 deaths.

Reservation system

Indian removal policies led to the current day reservation system which allocated territories to individual tribes. According to scholar

Indian removal policies led to the current day reservation system which allocated territories to individual tribes. According to scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker

Dina Gilio-Whitaker is an American academic, journalist and author, who studies Native Americans in the United States, decolonization and environmental justice. She is a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes. In 2019, she published '' As Lo ...

, "the treaties also created reservations that would confine Native people into smaller territories far smaller than they had for millenia been accustomed to, diminishing their ability to feed themselves." According to author and scholar David Rich Lewis, these reservations had much higher population densities than indigenous homelands. As a result, "the consolidation of native peoples in the 19th century allowed epidemic diseases to rage through their communities." In addition to this "a result of changing subsistence patterns and environments-contributed to an explosion of dietary-related illness like diabetes, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, cirrhosis, obesity, gallbladder disease, hypertension, and heart disease".

Once their territories were incorporated into the United States, surviving Native Americans were denied equality before the law and often treated as wards of the state. Many Native Americans were moved to reservations—constituting 4% of U.S. territory. In a number of cases, treaties signed with Native Americans were violated. Tens of thousands of American Indians and Alaska Natives were forced to attend a residential school system which sought to reeducate them in white-settler American values, culture, and economy.

Oceti Sakowin historian Nick Estes has called reservations "prisoner of war camps," citing forced removal and confinement. Reservations have historically had negative ecological effects on Native communities. The reservation system "offset the flourishing moral relationships that supported" Indigenous communities' resilience to changing environmental conditions. For instance, Whyte explains that being confined to a reservation jeopardizes Native communities' relationships with plants and animals located outside the scope of the reservation. Reservations also limit space for ceremonial practices and harvesting, and disrupt traditional seasonal rounds, which allowed Indigenous people to adapt to their environments.

Despite being forced onto reservations, Native Americans' right to that land and historical territory is not secured. Governments and private companies often take control of Indigenous land, or they use the reservation system to justify the control of Indigenous land that does not fall within the reservation. The Dakota Access Pipeline

The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) or Bakken pipeline is a underground pipeline in the United States that has the ability to transport up to 750,000 barrels of light sweet crude oil per day. It begins in the shale oil fields of the Bakken For ...

, for instance, cuts through ancestral Oceti Sakowin land, but historical dispossession then makes it seem to settlers that the pipeline today does not require Indigenous consent since it is off reservation. The Army Corps of Engineers has also taken Native land in Minnesota to construct a power plant, while waste sites are often placed close to reservations. House Concurrent Resolution 108, passed in 1953, attempted to withdraw federal protection of tribal lands and dissolve reservations. Many Native Americans were then relocated to cities. According to Kyle Powys Whyte

Kyle Powys Whyte is an Indigenous philosopher and climate/environmental justice scholar. He is a Professor of Environment and Sustainability and George Willis Pack Professor at the University of Michigan's School for Environment and Sustainability ...

, since the creation of the reservation system, "settlers eventually 'filled in' treaty areas and reservation areas with their own private property and government lands, which limit where and when Indigenous peoples can harvest, monitor, store and honor animals and plants... settler discourses cast Indigenous harvesters and gatherers as violating the 'law,' among many other types of stigmatizations." In June 2022, the Supreme Court ruled in '' Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta'' that Oklahoma has jurisdiction over Native reservations when a non-Native commits a crime against a Native. This contemporary decision further weakened Native control over their own reservation lands.

Genocidal campaigns

Stacie Martin states that the United States has not been legally admonished by the international community for genocidal acts against its Indigenous population, but many historians and academics describe events such as theMystic massacre

The Mystic massacrealso known as the Pequot massacre and the Battle of Mystic Forttook place on May 26, 1637 during the Pequot War, when a force from the Connecticut Colony under Captain John Mason and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies se ...

, the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

, the Sand Creek massacre

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the U.S. Army in the American Indian Genocide that occurred on No ...

and the Mendocino War as genocidal in nature.

The non-Native historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (born September 10, 1938) is an American historian, writer, professor, and activist based in San Francisco. Born in Texas, she grew up in Oklahoma and is a social justice and feminist activist. She has written numerous books ...

states that U.S. history, as well as inherited Indigenous trauma, cannot be understood without dealing with the genocide that the United States committed against Indigenous peoples. From the colonial period through the founding of the United States and continuing in the twentieth century, this has entailed torture, terror, sexual abuse, massacres, systematic military occupations, removals of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories via Indian removal policies, forced removal of Native American children to boarding schools, allotment, and a policy of termination.

The letters exchanged between Bouquet and Amherst during the Pontiac War show Amherst writing to Bouquet that the indigenous people needed to be exterminated: "You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race." Historians regard this as evidence of a genocidal intent by Amherst, as well as part of a broader genocidal attitude frequently displayed against Native Americans during the colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization, colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. Norse colonization of North ...

. When smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

swept the northern plains of the U.S. in 1837, the U.S. Secretary of War Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

ordered that no Mandan

The Mandan () are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still ...

(along with the Arikara

The Arikara ( ), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

, the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) ...

Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

, and the Blackfeet

The Blackfeet Nation (, ), officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Montana. Tribal members primarily belong ...

) be given smallpox vaccinations, which were provided to other tribes in other areas.

Historian Jeffrey Ostler describes the Colorado territorial militia's slaughter of Cheyennes at Sand Creek (1864) and the army's slaughter of Shoshones at Bear River (1863), Blackfeet on the Marias River (1870), and Lakotas at Wounded Knee (1890) as "genocidal massacres".

California

The U.S. colonization of California started in earnest in 1846, with theMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. With the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

, it gave the United States authority over 525,000 square miles of new territory. Following the Gold Rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, ...

, there were a number of killings and state-subsidized massacres by settlers against Native Americans in the territory, causing several ethnic groups to be nearly wiped out. In one such series of conflicts, the so-called Mendocino War and the subsequent Round Valley War, the entirety of the Yuki people

The Yuki (also known as Yukiah) are an Indigenous people of California who were traditionally divided into three groups: ''Ukomno'om'' ("Valley People", or Yuki proper), ''Huchnom'' ("Outside the Valley"), and ''Ukohtontilka'' or ''Ukosontilka'' ...

was brought to the brink of extinction. From a previous population of some 6,800 people, fewer than 300 members of the Yuki tribe were left.

The pre-Columbian population of California was around 300,000. By 1849, due to epidemics, the number had decreased to 100,000. But from 1849 to 1870 the indigenous population of California had fallen to 35,000 because of killings and displacement. At least 4,500 California Indians were killed between 1849 and 1870, while many more were weakened and perished due to disease and starvation. 10,000 Indians were also kidnapped and sold as slaves. In a speech before representatives of Native American peoples in June 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom

Gavin Christopher Newsom ( ; born October 10, 1967) is an American politician and businessman serving since 2019 as the 40th governor of California. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served from 2011 to 201 ...

apologized for the genocide. Newsom said, "That's what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that's the way it needs to be described in the history books."

Whites hunted down adult Indians in the mountains, kidnapped their children, and sold them as apprentices for as little as $50. Indians could not complain in court because of a California statute that stated that 'no Indian or Black or Mulatto person was permitted to give evidence in favor of or against a white person'. One contemporary wrote, "The miners are sometimes guilty of the most brutal acts with the Indians... such incidents have fallen under my notice that would make humanity weep and men disown their race". The towns of Marysville and Honey Lake paid bounties for Indian scalps. Shasta City authorities offered $5 for every Indian head brought to them.

American Indian wars

During theIndian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States of America and Republic of Texas agains ...

, the American Army carried out a number of massacres and forced relocations of Indigenous peoples that are sometimes considered genocide. Jeffrey Ostler, the Beekman Professor of Northwest and Pacific History at the University of Oregon

The University of Oregon (UO, U of O or Oregon) is a Public university, public research university in Eugene, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1876, the university is organized into nine colleges and schools and offers 420 undergraduate and gra ...

, stated the American Indian War "was genocidal war". Xabier Irujo, professor of genocide studies

Genocide studies is an academic field of study that researches genocide. Genocide became a field of study in the mid-1940s, with the work of Raphael Lemkin, who coined ''genocide'' and started genocide research, and its primary subjects were the ...

at the University of Nevada, Reno

The University of Nevada, Reno (Nevada, the University of Nevada, or UNR) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Reno, Nevada, United States. It is the state's flagship public university and prim ...

, stated, "the toll on human lives in the wars against the native nations between 1848 and 1881 was horrific." Notable conflicts in this period include the Dakota War

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several eastern bands of Dakota collectiv ...

, Great Sioux War

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota people, Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of t ...

, Comanche campaign, Snake War

The Snake War (1864–1868) was an Irregular warfare, irregular war fought by the United States of America against the "Snake Indians," the Exonym, settlers' term for Northern Paiute, Bannock (tribe), Bannock and Western Shoshone bands who liv ...

and Colorado War. These conflicts occurred in the United States from the time of the earliest colonial settlements in the 17th century until the end of the 19th century. The wars resulted from several factors, the most common being the desire of settlers and governments for Indian tribes' lands.

The 1864 Sand Creek massacre

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the U.S. Army in the American Indian Genocide that occurred on No ...

, which caused outrage in its own time, has been regarded as a genocide. Colonel John Chivington led a 700-man force of Colorado Territory

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861, until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the 38th State of Colorado.

The territory was organized ...

militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

in a massacre of 70–163 peaceful Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. The Cheyenne comprise two Native American tribes, the Só'taeo'o or Só'taétaneo'o (more commonly spelled as Suhtai or Sutaio) and the (also spelled Tsitsistas, The term for th ...

and Arapaho

The Arapaho ( ; , ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho bands formed t ...

, about two-thirds of whom were women, children, and infants. Chivington and his men took scalps and other body parts as trophies, including human fetus

A fetus or foetus (; : fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo. Following the embryonic development, embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Pren ...

es and male and female genitalia

A sex organ, also known as a reproductive organ, is a part of an organism that is involved in sexual reproduction. Sex organs constitute the primary sex characteristics of an organism. Sex organs are responsible for producing and transporting ...

.United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1865 (testimonies and report) Chivington stated, "Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! ... I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God's heaven to kill Indians. ... Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice."

Cultural genocide

In reference to colonialism in the United States,

In reference to colonialism in the United States, Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin (; 24 June 1900 – 28 August 1959) was a Polish lawyer who is known for coining the term "genocide" and for campaigning to establish the Genocide Convention, which legally defines the act. Following the German invasion of Poland ...

stated that the "colonial enslavement of American Indians was a cultural genocide." He also stated that colonialism in the United States comprised an "effective and thorough method of destroying a culture and de-socializing human beings". Lemkin drew a distinction between "cultural change and cultural genocide". He defined the former as a slow and gradual process of transition to new situations, and he saw the latter as the result of a radical and violent change that necessitated "the pre-meditated goal of those committing cultural genocide". Lemkin believed that cultural genocide occurs only when there are "surgical operations on cultures and deliberate assassinations of civilizations".

Historian Patrick Wolfe

Patrick Wolfe (1949 – 18 February 2016) was an English historian and scholar who lived and wrote in Australia.

Born into an Irish Catholic and German Jewish family in Yorkshire, England, his works are credited with establishing the field of ...

coined the term "logic of elimination" to describe the "relationship between genocide and the settler-colonial tendency." He points to the racialization of Native Americans and the proliferation of blood quantum laws

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws that define Native Americans in the United States status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to establish ...

as a means to reduce Native populations and further the logic of elimination. Wolfe also describes the non-physical nature of the logic of elimination and the way it is carried out, claiming that "officially encouraged miscegenation, the breaking-down of native title into alienable individual freeholds, native citizenship, child abduction, religious conversion, resocialization in total institutions such as missions or boarding schools, and a whole range of cognate biocultural assimilations" all facilitated colonial settlement.

According to Vincent Schilling, many people are aware of historical atrocities that were committed against his people, but there is an "extensive amount of misunderstanding about Native American and First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

people's history." He added that Native Americans have also suffered a "cultural genocide" because of colonization's residual effects.

The American-Indian experience in North America is defined as comprising physical and cultural disintegration. That fact becomes clear when one examines how law and colonialism were used as tools of genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

, both physically and culturally. According to Luana Ross the assumption that law (a Euro-American construct) and its administration are prejudiced against particular groups of individuals is critical for understanding Native American criminality and the experiences of Natives imprisoned. For instance, in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, the 1789 act permitted indiscriminate massacre of Creek Indians by proclaiming them to be outside the state's protection. Apart from physical annihilation, the State promoted acculturation by introducing legislation limiting land entitlements to Indians who had abandoned tribal citizenship.

Throughout the writing of the Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was ...

, the United States was adamantly opposed to the addition of cultural genocide, even threatening to block the treaty's approval if cultural genocide was included in the final text.

Forced assimilation

The Native American boarding school system was a 150-year program and federal policy that separated Indigenous children from their families and sought to assimilate them into white society. It began in the early 19th century, coinciding with the start of Indian Removal policies. A Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report was published on May 11, 2022, which officially acknowledged the federal government's role in creating and perpetuating this system. According to the report, the U.S. federal government operated or funded more than 408 boarding institutions in 37 states between 1819 and 1969. 431 boarding schools were identified in total, many of which were run by religious institutions.

The report described the system as part of a federal policy aimed at eradicating the identity of Indigenous communities and confiscating their lands. Abuse was widespread at the schools, as was overcrowding, malnutrition, disease and lack of adequate healthcare, all of which worsened the effect of disease. The report documented over 500 child deaths at 19 schools, although it is estimated the total number could rise to thousands, and possibly even tens of thousands.

Marked or unmarked burial sites were discovered at 53 schools. The school system has been described as a cultural genocide and a racist

The Native American boarding school system was a 150-year program and federal policy that separated Indigenous children from their families and sought to assimilate them into white society. It began in the early 19th century, coinciding with the start of Indian Removal policies. A Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report was published on May 11, 2022, which officially acknowledged the federal government's role in creating and perpetuating this system. According to the report, the U.S. federal government operated or funded more than 408 boarding institutions in 37 states between 1819 and 1969. 431 boarding schools were identified in total, many of which were run by religious institutions.

The report described the system as part of a federal policy aimed at eradicating the identity of Indigenous communities and confiscating their lands. Abuse was widespread at the schools, as was overcrowding, malnutrition, disease and lack of adequate healthcare, all of which worsened the effect of disease. The report documented over 500 child deaths at 19 schools, although it is estimated the total number could rise to thousands, and possibly even tens of thousands.

Marked or unmarked burial sites were discovered at 53 schools. The school system has been described as a cultural genocide and a racist dehumanization

upright=1.2, link=Warsaw Ghetto boy, In his report on the suppression of the Nazi camps as "bandits".