Frederick Funston on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

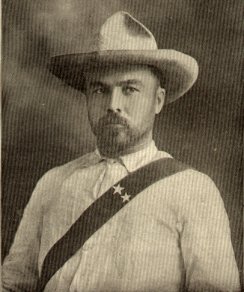

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a

He eventually joined the

He eventually joined the

The

The

In 1906, Funston was commander of the

In 1906, Funston was commander of the

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel

20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry

;Place and date: :At Rio Grande de la Pampanga,

"Funston, Frederick"

in ''The National Cyclopedia of American Biography,'' Vol. 11, pp. 40–41.

Frederick Funston

are available on Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

Frederick Funston papers

are available at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas * {{DEFAULTSORT:Funston, Frederick 1865 births 1906 San Francisco earthquake 1917 deaths United States Army Medal of Honor recipients American military personnel of the Banana Wars American military personnel of the Philippine–American War American military personnel of the Spanish–American War United States Army generals University of Kansas alumni Commandants of the United States Army Command and General Staff College Philippine–American War recipients of the Medal of Honor Burials at San Francisco National Cemetery People from New Carlisle, Ohio People from Iola, Kansas Military personnel from Ohio American expatriates in the Philippines

general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

and the Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War or Filipino–American War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

. He received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

for his actions during the Philippine–American War.

Early life, education, and work

Funston was born in 1865 inNew Carlisle, Ohio

New Carlisle is a city in Clark County, Ohio, Clark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,785 at the United States Census 2010, 2010 census. It is part of the Springfield, Ohio Springfield, Ohio metropolitan area, Metropolitan Statistic ...

, to Edward H. Funston

Edward Hogue Funston (September 16, 1836 – September 10, 1911) was a U.S. Representative from Kansas.

Biography

Funston was born near New Carlisle, Ohio on September 16, 1836. He attended the country schools of New Carlisle, Linden Hil ...

and Anne Eliza ''Mitchell'' Funston. In 1867, his family moved to Allen County, Kansas

Allen County (county code AL) is a county located in the southeast portion of the U.S. state of Kansas. It is 504 square miles, or 322,560 acres in size. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,526. Its county seat and most populous city ...

. His father was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

in 1884 and served five terms.

Funston was a slight individual who stood tall and weighed only when he applied in 1886 to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

; he was rejected. Funston graduated from Iola High School

Iola High School is a fully accredited high school located in Iola, Kansas, United States, serving students in grades 9–12. The current principal is Scott Carson. The mascot is Marv the Mustang. The school colors are blue and gold.

Extracurric ...

in 1886. He attended the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. T ...

from 1886 to 1890. While there, he joined the Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta (), commonly known as Phi Delt, is an international secret and social fraternity founded at Miami University in 1848 and headquartered in Oxford, Ohio. Phi Delta Theta, along with Beta Theta Pi and Sigma Chi form the Miami Triad. ...

fraternity and became friends with William Allen White

William Allen White (February 10, 1868 – January 29, 1944) was an American newspaper editor, politician, author, and leader of the Progressive movement. Between 1896 and his death, White became a spokesman for middle America.

At a 193 ...

, who became a writer and won a Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

. He worked as a trainman for the Santa Fe Railroad

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States. The railroad was chartered in February 1859 to serve the cities of Atchison and Topeka, Kansas, and ...

before becoming a reporter in Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the List of United States cities by populat ...

, in 1890.

Career

After one year as ajournalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalis ...

, Funston moved into more scientific exploration, focusing primarily on botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

. First serving as part of an exploring and surveying expedition in Death Valley, California

Death Valley is a desert valley in Eastern California, in the northern Mojave Desert, bordering the Great Basin Desert. During summer, it is the hottest place on Earth.

Death Valley's Badwater Basin is the point of lowest elevation in North A ...

. In 1891, he then traveled to Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

to spend the next two years in work for the United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

.

Cuba

He eventually joined the

He eventually joined the Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

n Revolutionary Army that was fighting for independence from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

in 1896 after having been inspired to join following a rousing speech given by Gen. Daniel E. Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819May 3, 1914) was an American politician, soldier, and diplomat.

Born to a wealthy family in New York City, Sickles was involved in a number of scandals, most notably the 1859 homicide of his wife's lover, U. ...

at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylv ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

After a bout of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, Funston's weight dropped to an alarming 95 lb. The Cubans gave him a leave of absence. When Funston returned to the United States, he was commissioned as a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

of the 20th Kansas Infantry Regiment in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

on May 13, 1898, in the early days of the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. In the fall, he met Eda Blankart at a patriotic gathering, and after a brief courtship, they married on October 25, 1898. Within two weeks of the marriage, he had to depart for war, landing in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

as part of the U.S. forces that would become engaged in the Philippine–American War.

Philippines

Funston was in command in various engagements with Filipino nationalists. In April 1899, he took a Filipino position atCalumpit

Calumpit, officially the Municipality of Calumpit ( tgl, Bayan ng Calumpit), is a 1st class municipality in the province of Bulacan, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 118,471 people.

Etymology

The name "''Calu ...

by swimming the Bagbag River, then crossing the Pampanga River

The Pampanga River is the second largest river on the island of Luzon in the Philippines (next to Cagayan River) and the country's fifth longest river. It is in the Central Luzon region and traverses the provinces of Pampanga, Bulacan, and Nueva ...

under heavy fire. For his bravery, Funston was soon promoted to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers and awarded the Medal of Honor on February 14, 1900.

Funston played the key role in planning and executing the capture of Filipino President Emilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who is the youngest president of the Philippines (1899–1901) and is recognized as the first president of the Philippine ...

on March 23, 1901, at Palanan. The capture of Aguinaldo made Funston a national hero, although the anti-imperialist faction criticized him when the details of the capture became known. Funston's party, escorted by a company of Macabebe scouts, had gained access to Aguinaldo's camp by posing as prisoners of Macabebe scouts. Funston's mission to capture Aguinaldo brought him a Regular Army commission just as he was scheduled to be mustered out of the volunteer service and, at only 35 years old, Funston was appointed a brigadier general in the Regular Army in recognition of his capture of Aguinaldo.

In 1902, Funston returned to the United States to increased public opposition to the Philippine–American War, and became the focus of a great deal of controversy. Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has pr ...

, a strong opponent of U.S. imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic powe ...

, published a sarcasm-filled denunciation of Funston's mission and methods under the title "A Defence of General Funston

"A Defence of General Funston" is a satirical piece written by Mark Twain lampooning US Army General and expansionism advocate Frederick Funston. Funston had been a colonel during the Spanish–American and Philippine–American Wars, and Twain h ...

" in the ''North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (NAR) was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which it was inactive until revived at ...

''. Poet Ernest Crosby

Ernest Howard Crosby (November 4, 1856 – January 3, 1907) was an American reformer, georgist, and author.

Early life

Crosby was born in New York City in 1856. He was the son of the Rev. Dr. Howard Crosby (1826-1891), a Presbyterian ministe ...

also wrote a satirical, anti-imperialist novel, '' Captain Jinks, Hero'', that parodied the career of Funston.

Funston was considered a useful advocate for American expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

, but when he publicly made insulting remarks about anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 to 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politically prominen ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, mocking his "overheated conscience" in Denver, just before a planned trip to Boston, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

denied his furlough request, and ordered him silenced and officially reprimanded.

Sideco House

Sideco House

The Sideco House, also called the Crispulo Sideco House ( fil, Bahay Crispulo Sideco, italic=unset), is a historic house located in San Isidro, Nueva Ecija, Philippines, close to the Pampanga River. It was once the headquarters of the First Phili ...

was used as the seat of General Emilio Aguinaldo's First Philippine Republic; he established it as his headquarters in San Isidro during the last part of his escape from the American forces (after the Battle of Tirad Pass).

On March 29, 1899, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo arrived in San Isidro, Nueva Ecija

San Isidro, officially the Municipality of San Isidro,( tgl, Bayan ng San Isidro), is a 2nd class municipality in the province of Nueva Ecija, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 54,372 people.

The municipality is bo ...

, and proclaimed the town as capital of the First Philippine Republic. He stayed in the house, using it as the ''de facto'' base of the Philippine government.

After the Americans occupied San Isidro, the Sideco house served as Funston's headquarters. He later captured General Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela. The Americans were said to have planned the actions in this house that led to General Aguinaldo's capture. It is now occupied by a Christian organization.

United States and overseas again

In 1906, Funston was commander of the

In 1906, Funston was commander of the Presidio of San Francisco

The Presidio of San Francisco (originally, El Presidio Real de San Francisco or The Royal Fortress of Saint Francis) is a park and former U.S. Army post on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, and is part ...

when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity ...

hit. He declared martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

, although he did not have the authority to do so, and martial law was never officially declared. Funston attempted to defend the city from the spread of fire, and directed the demolition of buildings using explosives, including black powder, artillery charges, and dynamite, to create firebreak

A firebreak or double track (also called a fire line, fuel break, fireroad and firetrail in Australia) is a gap in vegetation or other combustible material that acts as a barrier to slow or stop the progress of a bushfire or wildfire. A firebr ...

s, but his orders often resulted in more fires. Funston gave orders to shoot all looters on sight; however, these orders resulted in numerous cases of innocent people being shot.

At the corner of Market and Third Streets on Wednesday, I saw a man attempt to cut the fingers from the hand of a dead woman in order to secure the rings which adorned the stiffened fingers. One man made the trooper believe that one of the dead bodies lying on a pile of rocks was his mother, and he was permitted to go up to the body. Apparently overcome by grief, he threw himself across the corpse. In another instant the soldiers discovered that he was chewing the diamond earrings from the ears of the dead woman ... The diamonds were found in the man's mouth afterward. The soldiers do all they can, and while the unspeakable crime of robbing the dead is undoubtedly being practiced, it would be many times more prevalent were it not for the constant vigilance on all sides, as well as the summary justice. – from survivors' accounts immediately following the 1906 Earthquake.At the time, local officials praised Funston's actions in the earthquake and fire emergency. Historians have since taken issue with some of his actions in the disaster. Specifically, they argue that he should not have used military forces in a peacetime emergency. From December 1907 through March 1908, Funston was in charge of troops at the Goldfield mining center in

Esmeralda County, Nevada

Esmeralda County is a county in the southwestern portion of the U.S. state of Nevada. As of the 2020 census, the population was 729, making it the least populous county in Nevada. Esmeralda County does not have any incorporated communities. It ...

, where the army put down a labor strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the ...

by the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

.

After two years as commandant of the Army Service School in Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Funston served three years as commander of the Department of Luzon in the Philippines. He was briefly shifted to the same role in the Hawaiian Department (April 3, 1913 to January 22, 1914).

Funston was active in the United States' conflict with Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

in 1914 to 1916, as commanding general of the army's Southern Department, being promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

in November 1914. He was commander of Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

in San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, where he prodded Second Lieutenant Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War I ...

into becoming the football coach for the Peacock Military Academy

The Peacock Military Academy was a college-preparatory school in San Antonio, Texas.

It was founded in 1894 by Dr. Wesley Peacock, Sr., who envisioned "the most thorough military school west of the Mississippi, governed by the honor system, and c ...

and later approved Eisenhower's request of leave for his wedding. He occupied the city of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

. He commanded all forces involved in the hunt for Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

, and provided security for the United States border with Mexico during the "Bandit War

The Bandit War, or Bandit Wars, was a series of raids in Texas that started in 1915 and finally culminated in 1919. They were carried out by Mexican rebels from the states of Tamaulipas, Coahuila, and Chihuahua. Prior to 1914, the Carrancistas ha ...

".

World War I and death

Shortly before theAmerican entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

, in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

favored Funston to head any American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

(AEF) that would be sent overseas. His intense focus on work led to health problems, first with a case of indigestion in January 1917, followed a month later by a fatal heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

at the age of 51 in San Antonio, Texas

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

.

In the moments before his death, Funston was relaxing in the lobby of the St. Anthony Hotel in San Antonio, listening to an orchestra play ''The Blue Danube

"The Blue Danube" is the common English title of "An der schönen blauen Donau", Op. 314 (German for "By the Beautiful Blue Danube"), a waltz by the Austrian composer Johann Strauss II, composed in 1866. Originally performed on 15 Februa ...

'' waltz

The waltz ( ), meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom and folk dance, normally in triple ( time), performed primarily in closed position.

History

There are many references to a sliding or gliding dance that would evolve into the wa ...

. After commenting, "How beautiful it all is," he collapsed from a massive, painful heart attack (myocardial infarction) and died. He was holding six-year-old Inez Harriett Silverberg in his arms.Tuesday, February 20, 1917 ''Omaha World-Herald'' (Omaha, Nebraska) p. 1

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

, then a major, had the unpleasant duty of breaking the news to President Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

. As MacArthur explained in his memoirs, "had the voice of doom spoken, the result could not have been different. The silence seemed like that of death itself. You could hear your own breathing."

Funston lay in state at both the Alamo

The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna reclaimed the Alamo Mission near San An ...

and the City Hall Rotunda in San Francisco. The latter honor gave him the distinction of being the first person to be recognized with this tribute, with his subsequent burial taking place in San Francisco National Cemetery

San Francisco National Cemetery is a United States national cemetery, located in the Presidio of San Francisco, California. Because of the name and location, it is frequently confused with Golden Gate National Cemetery, a few miles south of th ...

. After his death, his position of AEF commander went to Major General John J. Pershing, who, as commanding general of the Punitive Expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

in 1916, had been Funston's subordinate. The Lake Merced

, image =Lake Merced at SFSU.jpg

, caption =

, location = San Francisco, California

, coords =

, type = Reservoir

, inflow = Spring

, outflow =

, catchment =

, basi ...

military reservation (part of San Francisco's coastal defenses) was renamed Fort Funston

Fort Funston is a former harbor defense installation located in the southwestern corner of San Francisco. Formerly known as the Lake Merced Military Reservation, the fort is now a protected area within the Golden Gate National Recreation Are ...

in his honor, while the training camp built in 1917 next to Fort Riley in Kansas (which became the second-largest World War I camp) was named Camp Funston

Camp Funston is a U.S. Army training camp located on Fort Riley, southwest of Manhattan, Kansas. The camp was named for Brigadier General Frederick Funston (1865–1917). It is one of sixteen such camps established at the outbreak of World ...

. San Francisco's Funston Park and Funston Avenue are named for him, as is Funston Avenue in his hometown of New Carlisle, Ohio, and Funston Avenue near Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. In Hawaii, Funston Road at Schofield Barracks and Funston Road at Fort Shafter are named after him. Funston's daughter, and his son and grandson, both of whom served in the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Si ...

, were later interred with him.

Medal of Honor citation

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry

;Place and date: :At Rio Grande de la Pampanga,

Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, as ...

, Philippine Islands

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, April 27, 1899.

;Entered service at:

: Iola, Kansas.

;Birth:

:New Carlisle, Ohio

New Carlisle is a city in Clark County, Ohio, Clark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,785 at the United States Census 2010, 2010 census. It is part of the Springfield, Ohio Springfield, Ohio metropolitan area, Metropolitan Statistic ...

.

;Date of issue:

:February 14, 1900.

;Citation:

:Crossed the river on a raft and by his skill and daring enabled the general commanding to carry the enemy's entrenched position on the north bank of the river and to drive him with great loss from the important strategic position of Calumpit

Calumpit, officially the Municipality of Calumpit ( tgl, Bayan ng Calumpit), is a 1st class municipality in the province of Bulacan, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 118,471 people.

Etymology

The name "''Calu ...

.

Legacy

Fort Funston

Fort Funston is a former harbor defense installation located in the southwestern corner of San Francisco. Formerly known as the Lake Merced Military Reservation, the fort is now a protected area within the Golden Gate National Recreation Are ...

in San Francisco, California

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, is named for him.

Streets are named for Funston in San Francisco, New Carlisle, Ohio

New Carlisle is a city in Clark County, Ohio, Clark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,785 at the United States Census 2010, 2010 census. It is part of the Springfield, Ohio Springfield, Ohio metropolitan area, Metropolitan Statistic ...

, Reading, Pennsylvania, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Pacific Grove, California

Pacific Grove is a coastal city in Monterey County, California, in the United States. The population at the 2020 census was 15,090. Pacific Grove is located between Point Pinos and Monterey.

Pacific Grove has numerous Victorian-era houses, ...

, and Hollywood, Florida

Hollywood is a city in southern Broward County, Florida, United States, located between Fort Lauderdale and Miami. As of July 1, 2019, Hollywood had a population of 154,817. Founded in 1925, the city grew rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s, and is no ...

. Part of Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Ge ...

, Kansas, was also named for him.

In popular culture

* He was portrayed byTroy Montero

Cody Andrew Miller III (born July 30, 1971), known professionally as Troy Montero, is a Filipino-American actor.

He was born to an American father of German and Irish ancestry, and a U.S.-born Filipina mother. In 2008, he and girlfriend Aubre ...

in the 2012 Filipino film '' El Presidente''.

* He was portrayed by Pablo Espinosa in the 1997 TNT television series ''Rough Riders''.

* He was mentioned once in ''The Woggle-Bug Book'' by L. Frank Baum published in 1905.

See also

*List of Philippine–American War Medal of Honor recipients

The Philippine–American War was an armed military conflict between the United States and the First Philippine Republic, fought from 1899 to at least 1902, which arose from a Filipino political struggle against U.S. occupation of the Philippin ...

*A Defence of General Funston

"A Defence of General Funston" is a satirical piece written by Mark Twain lampooning US Army General and expansionism advocate Frederick Funston. Funston had been a colonel during the Spanish–American and Philippine–American Wars, and Twain h ...

(Mark Twain's satirical essay).

References

:Further reading

"Funston, Frederick"

in ''The National Cyclopedia of American Biography,'' Vol. 11, pp. 40–41.

External links

* * * Photos and other items related tFrederick Funston

are available on Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

Frederick Funston papers

are available at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas * {{DEFAULTSORT:Funston, Frederick 1865 births 1906 San Francisco earthquake 1917 deaths United States Army Medal of Honor recipients American military personnel of the Banana Wars American military personnel of the Philippine–American War American military personnel of the Spanish–American War United States Army generals University of Kansas alumni Commandants of the United States Army Command and General Staff College Philippine–American War recipients of the Medal of Honor Burials at San Francisco National Cemetery People from New Carlisle, Ohio People from Iola, Kansas Military personnel from Ohio American expatriates in the Philippines