François Rabelais on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

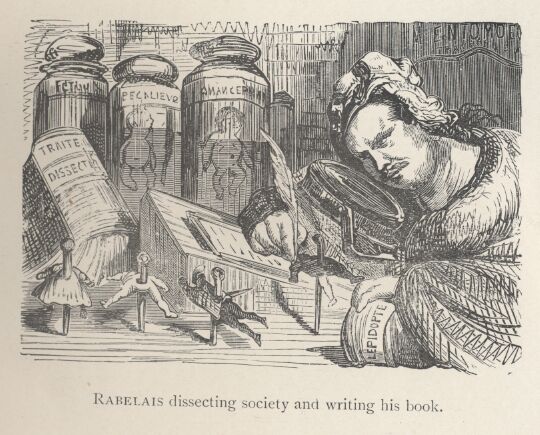

François Rabelais ( , ; ; born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a French writer who has been called the first great French prose author. A

In 1540, Rabelais lived for a short time in

In 1540, Rabelais lived for a short time in

''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' relates the adventures of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The tales are adventurous and erudite, festive and gross, ecumenical, and rarely—if ever—solemn for long. The first book, chronologically, was ''Pantagruel: King of the Dipsodes'' and the Gargantua mentioned in the Prologue refers not to Rabelais' own work but to storybooks that were being sold at the Lyon fairs in the early 1530s. In the first chapter of the earliest book, Pantagruel's lineage is listed back 60 generations to a giant named Chalbroth. The narrator dismisses the skeptics of the time—who would have thought a giant far too large for Noah's Ark—stating that Hurtaly (the giant reigning during the flood and a great fan of soup) simply rode the Ark like a kid on a rocking horse, or like a fat Swiss guy on a cannon.

In the Prologue to ''Gargantua'' the narrator addresses the: "Most illustrious drinkers, and ''you'' the most precious pox-riddenfor to ''you'' and ''you'' alone are my writings dedicated ..." before turning to Plato's ''

''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' relates the adventures of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The tales are adventurous and erudite, festive and gross, ecumenical, and rarely—if ever—solemn for long. The first book, chronologically, was ''Pantagruel: King of the Dipsodes'' and the Gargantua mentioned in the Prologue refers not to Rabelais' own work but to storybooks that were being sold at the Lyon fairs in the early 1530s. In the first chapter of the earliest book, Pantagruel's lineage is listed back 60 generations to a giant named Chalbroth. The narrator dismisses the skeptics of the time—who would have thought a giant far too large for Noah's Ark—stating that Hurtaly (the giant reigning during the flood and a great fan of soup) simply rode the Ark like a kid on a rocking horse, or like a fat Swiss guy on a cannon.

In the Prologue to ''Gargantua'' the narrator addresses the: "Most illustrious drinkers, and ''you'' the most precious pox-riddenfor to ''you'' and ''you'' alone are my writings dedicated ..." before turning to Plato's ''

Published in 1546 under his own name with the ''privilège'' granted by Francis I for the first edition and by Henri II for the 1552 edition, ''The Third Book'' was condemned by the Sorbonne, like the previous tomes. In it, Rabelais revisited discussions he had had while working as a secretary to Geoffroy d'Estissac earlier in Fontenay–le–Comte, where ''la querelle des femmes'' had been a lively subject of debate. More recent exchanges with Marguerite de Navarre—possibly about the question of clandestine marriage and the

Published in 1546 under his own name with the ''privilège'' granted by Francis I for the first edition and by Henri II for the 1552 edition, ''The Third Book'' was condemned by the Sorbonne, like the previous tomes. In it, Rabelais revisited discussions he had had while working as a secretary to Geoffroy d'Estissac earlier in Fontenay–le–Comte, where ''la querelle des femmes'' had been a lively subject of debate. More recent exchanges with Marguerite de Navarre—possibly about the question of clandestine marriage and the  In contrast to the two preceding chronicles, the dialogue between the characters is much more developed than the plot elements in the third book. In particular, the central question of the book, which Panurge and Pantagruel consider from multiple points of view, is an abstract one: whether Panurge should marry or not. Torn between the desire for a wife and the fear of being cuckolded, Panurge engages in divinatory methods, like dream interpretation and bibliomancy. He consults authorities vested with revealed knowledge, like the sibyl of Panzoust or the mute Nazdecabre, profane acquaintances, like the theologian Hippothadée or the philosopher Trouillogan, and even the jester Triboulet. It is likely that several of the characters refer to real people: Abel Lefranc argues that Hippothadée was Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, Rondibilis was the doctor Guillaume Rondelet, the

In contrast to the two preceding chronicles, the dialogue between the characters is much more developed than the plot elements in the third book. In particular, the central question of the book, which Panurge and Pantagruel consider from multiple points of view, is an abstract one: whether Panurge should marry or not. Torn between the desire for a wife and the fear of being cuckolded, Panurge engages in divinatory methods, like dream interpretation and bibliomancy. He consults authorities vested with revealed knowledge, like the sibyl of Panzoust or the mute Nazdecabre, profane acquaintances, like the theologian Hippothadée or the philosopher Trouillogan, and even the jester Triboulet. It is likely that several of the characters refer to real people: Abel Lefranc argues that Hippothadée was Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, Rondibilis was the doctor Guillaume Rondelet, the

Rabelais.nl

sur l

Portail de la Renaissance française

François Rabelais Museum on the Internet

* Henry Émile Chevalier, , 1868 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rabelais, Francois 1553 deaths 15th-century births 16th-century French male writers 16th-century French novelists 16th-century French physicians 16th-century French writers 16th-century Roman Catholics French Benedictines French Franciscans French Renaissance humanists French Renaissance French Roman Catholic writers French male novelists French male poets French medical writers People from Indre-et-Loire Thelema University of Montpellier alumni University of Poitiers alumni Writers from Centre-Val de Loire

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

of the French Renaissance

The French Renaissance was the cultural and artistic movement in France between the 15th and early 17th centuries. The period is associated with the pan-European Renaissance, a word first used by the French historian Jules Michelet to define ...

and Greek scholar, he attracted opposition from both Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

theologian John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

and from the hierarchy of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Though in his day he was best known as a physician, scholar, diplomat, and Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' refe ...

, later he became better known as a satirist

This is an incomplete list of writers, cartoonists and others known for involvement in satire – humorous social criticism. They are grouped by era and listed by year of birth. Included is a list of modern satires.

Early satirical authors

*Aes ...

for his depictions of the grotesque, and for his larger-than-life characters.

Living in the religious and political turmoil of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, Rabelais treated the great questions of his time in his novels. Rabelais admired Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

and like him is considered a Christian humanist. He was critical of medieval scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

and lampooned the abuses of powerful princes and popes.

Rabelais is widely known for the first two volumes relating the childhoods of the giants Gargantua and Pantagruel

''The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel'' (), often shortened to ''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' or the (''Five Books''), is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais. It tells the advent ...

written in the style of ''bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a bildungsroman () is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth and change of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age). The term comes from the German words ('formation' or 'edu ...

''; his later works—the ''Third Book'' (which prefigures the philosophical novel) and the ''Fourth Book'' are considerably more erudite in tone. His literary legacy gave rise to the word '' Rabelaisian'', an adjective meaning "marked by gross robust humor, extravagance of caricature, or bold naturalism."

Biography

Touraine countryside to monastic life

According to a tradition dating back to Roger de Gaignières (1642–1715), François Rabelais was the son ofseneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

and lawyer Antoine Rabelais and was born at the estate of ''La Devinière'' in Seuilly (near Chinon

Chinon () is a Communes of France, commune in the Indre-et-Loire Departments of France, department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

The traditional province around Chinon, Touraine, became a favorite resort of French kings and their nobles beginn ...

), Touraine in modern-day Indre-et-Loire

Indre-et-Loire () is a department in west-central France named after the Indre River and Loire River. In 2019, it had a population of 610,079.trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but the term was not used until the Carolin ...

syllabus that included the study of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic before moving on to the quadrivium, which dealt with arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

In 1623, Jacques Bruneau de Tartifume wrote that Rabelais began his life as a novice

A novice is a person who has entered a religious order and is under probation, before taking vows. A ''novice'' can also refer to a person (or animal e.g. racehorse) who is entering a profession with no prior experience.

Religion Buddhism

...

of the Franciscan Order of Cordeliers, at the Convent of the Cordeliers, near Angers

Angers (, , ;) is a city in western France, about southwest of Paris. It is the Prefectures of France, prefecture of the Maine-et-Loire department and was the capital of the province of Duchy of Anjou, Anjou until the French Revolution. The i ...

; however there is no direct evidence to support this theory. By 1520, he was at Fontenay-le-Comte

Fontenay-le-Comte (; Poitevin dialect, Poitevin: ''Funtenaes'' or ''Fintenè'') is a Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture in the Vendée Departments of France, department in the Pays de la Loire Regions of France ...

in Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

where he became friends with Pierre Lamy, a fellow Franciscan, and corresponded with Guillaume Budé, who observed that he was already competent in law. Following Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

' commentary on the original Greek version of the ''Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke is the third of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It tells of the origins, Nativity of Jesus, birth, Ministry of Jesus, ministry, Crucifixion of Jesus, death, Resurrection of Jesus, resurrection, and Ascension of ...

'', the Sorbonne banned the study of Greek in 1523, believing that it encouraged "personal interpretation" of the New Testament. As a result, both Lamy and Rabelais had their Greek books confiscated. Frustrated by the ban, Rabelais petitioned Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate o ...

(1523–1534) and obtained an indult with the help of Bishop , and was able to leave the Franciscans for the Benedictine Order

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly Christian mysticism, contemplative Christian monasticism, monastic Religious order (Catholic), order of the Catholic Church for men and f ...

at Maillezais. At the Saint-Pierre-de-Maillezais abbey, he worked as a secretary to the bishop—a well-read prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Minister (Christianity), Christian clergy who is an Ordinary (church officer), ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which me ...

appointed by Francis I—and enjoyed his protection.

Physician and author

Around 1527 he left the monastery without authorization, becoming an apostate untilPope Paul III

Pope Paul III (; ; born Alessandro Farnese; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death, in November 1549.

He came to the papal throne in an era follo ...

absolved him of this crime, which carried with it the risk of severe sanctions, in 1536. Until this time, church law forbade him to work as a doctor or surgeon. J. Lesellier surmises that it was during the time he spent in Paris from 1528 to 1530 that two of his three children (François and Junie) were born. After Paris, Rabelais went to the University of Poitiers

The University of Poitiers (UP; , ) is a public university located in Poitiers, France. It is a member of the Coimbra Group. It is multidisciplinary and contributes to making Poitiers the city with the highest student/inhabitant ratio in France ...

and then to the University of Montpellier

The University of Montpellier () is a public university, public research university located in Montpellier, in south-east of France. Established in 1220, the University of Montpellier is one of the List of oldest universities in continuous opera ...

to study medicine. In 1532 he moved to Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, one of the intellectual centres of the Renaissance, and began working as a doctor at the hospital Hôtel-Dieu de Lyon. During his time in Lyon, he edited Latin works for the printer Sebastian Gryphius, and wrote a famous admiring letter to Erasmus to accompany the transmission of a Greek manuscript from the printer. Gryphius published Rabelais' translations and annotations of Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

and Giovanni Manardo. In 1537 he returned to Montpellier to pay the fees to obtain his licence to practice medicine (April 3) and obtained his doctorate the following month (May 22). Upon his return to Lyon in the summer, he gave an anatomy lesson at Lyon's Hôtel-Dieu using the corpse of a hanged man, which Etienne Dolet described in his ''Carmina''. It was through his work and scholarship in the field of medicine that Rabelais gained European fame.

In 1532, under the pseudonym Alcofribas Nasier (an anagram

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word ''anagram'' itself can be rearranged into the phrase "nag a ram"; which ...

of François Rabelais), he published his first book, ''Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes'', the first of his ''Gargantua'' series, primarily to supplement his income at the hospital. The idea of basing an allegory on the lives of giants came to Rabelais from the folklore legend of ''les Grandes chroniques du grand et énorme géant Gargantua'', which were sold by colporteurs and at the as popular literature in the form of inexpensive pamphlets. The first edition of an almanac parodying the astrological predictions of the time called ''Pantagrueline prognostications'' appeared for the year 1533 from the press of Rabelais' publisher François Juste. It contained the name "Maître Alcofribas" in its full title. The popular almanacs continued irregularly until the final 1542 edition, which was prepared for the "perpetual year". From 1537, they were printed at the end of Juste's editions of ''Pantagruel''. Pantagruelism is an "eat, drink and be merry" philosophy, which led his books into disfavor with the theologians but brought them popular success and the admiration of later critics for their focus on the body. This first book, critical of the existing monastic and educational system, contains the first known occurrence in French of the words ''encyclopédie'', ''caballe'', ''progrès'', and ''utopie'', among others. The book became popular, along with its 1534 prequel

A prequel is a literary, dramatic or cinematic work whose story precedes that of a previous work, by focusing on events that occur before the original narrative. A prequel is a work that forms part of a backstory to the preceding work.

The term ...

, which dealt with the life and exploits of Pantagruel's father Gargantua, and which was more infused with the politics of the day and overtly favorable to the monarchy than the preceding volume had been. The 1534 re-edition of ''Pantagruel'' contains many orthographic, grammatical, and typographical innovations, in particular the use of diacritics (accents, apostrophes, and diaereses), which was then new in French. Mireille Huchon ascribes this innovation in part to the influence of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

's ''De vulgari eloquentia

''De vulgari eloquentia'' (, ; "On eloquence in the vernacular") is the title of a Latin essay by Dante Alighieri. Although meant to consist of four books, it abruptly terminates in the middle of the second book. It was probably composed shortly ...

'' on French letters.

Travel to Italy

No clear evidence establishes when Jean du Bellay and Rabelais met. Nevertheless, when du Bellay was sent to Rome in January 1534 to convince Pope Clément VII not to excommunicateHenry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, he was accompanied by Rabelais, who worked as his secretary and personal physician until his return in April. During his stay, Rabelais found the city fascinating and decided to bring out a new edition of Bartolomeo Marliani

Giovanni Bartolomeo Marliano (1488 Massimiliano Albanese'Bartolomeo Marliani'in ''Dizionario biografico degli italiani'', vol. 70, Roma, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana - 26 July 1566) was an Italian antiquarian and topography, topographer, ...

's ''Topographia antiqua Romae'' with Sebastien Gryphe in Lyon.

Rabelais quietly left the Hôtel Dieu de Lyon on 13 February 1535 after receiving his salary, disappearing until August 1535 as a result of the tumultuous Affair of the Placards, which led Francis I to issue an edict forbidding all printing in France. Only the influence of the du Bellays allowed the printing presses to run again. In May, Jean du Bellay was named cardinal, and still with a diplomatic mission for Francis I, had Rabelais join him in Rome. During this time, Rabelais was also working for Geoffroy d'Estissac's interests and maintained a correspondence with him through diplomatic channels (under royal seal as far as Poitiers). Three letters from Rabelais have survived. On 17 January 1536, Paul III issued a papal brief authorizing Rabelais to join a Benedictine monastery and practice medicine, as long as he refrained from surgery. Jean du Bellay having been named the abbot ''in commendam'' of the Saint-Maur Abbey, Rabelais arranged to be assigned there, knowing that the monks were to become secular clergy the following year.

In 1540, Rabelais lived for a short time in

In 1540, Rabelais lived for a short time in Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

as part of the household of du Bellay's brother, Guillaume. It was at this time that his two children were legitimized by Paul III, the same year that his third child (Théodule) died in Lyon at the age of two. Rabelais also spent some time lying low, under periodic threat of being condemned of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

depending upon the health of his various protectors. In 1543, both ''Gargantua'' and ''Pantagruel'' were condemned by the Sorbonne, then a theological college. Only the protection of du Bellay saved Rabelais after the condemnation of his novel by the Sorbonne. In June 1543 Rabelais became a Master of Requests. Between 1545 and 1547 François Rabelais lived in Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

, then a free imperial city and a republic, to escape the condemnation by the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

. In 1547, he became curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are as ...

of Saint-Christophe-du-Jambet in Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and of Meudon

Meudon () is a French Communes of France, commune located in the Hauts-de-Seine Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France Regions of France, region, on the left bank of the Seine. It is located from the Kilometre Zero, center of P ...

near Paris.

With support from members of the prominent du Bellay family, Rabelais had received approval from King Francis I to continue to publish his collection on 19 September 1545 for six years. However, on 31 December 1546, the ''Tiers Livre'' joined the Sorbonne's list of banned books. After the king's death in 1547, the academic élite frowned upon Rabelais, and the Paris Parlement

Under the French Ancien Régime, a ''parlement'' () was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 ''parlements'', the original and most important of which was the ''Parlement'' of Paris. Though both th ...

suspended the sale of The Fourth Book, published in 1552, despite Henry II having accorded him the royal privilege. This suspension proved ineffective, for the time being, as the king reiterated his support for the book.

Rabelais resigned from the curacy in January 1553 and died in Paris later that year.

Novels

''Gargantua and Pantagruel''

''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' relates the adventures of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The tales are adventurous and erudite, festive and gross, ecumenical, and rarely—if ever—solemn for long. The first book, chronologically, was ''Pantagruel: King of the Dipsodes'' and the Gargantua mentioned in the Prologue refers not to Rabelais' own work but to storybooks that were being sold at the Lyon fairs in the early 1530s. In the first chapter of the earliest book, Pantagruel's lineage is listed back 60 generations to a giant named Chalbroth. The narrator dismisses the skeptics of the time—who would have thought a giant far too large for Noah's Ark—stating that Hurtaly (the giant reigning during the flood and a great fan of soup) simply rode the Ark like a kid on a rocking horse, or like a fat Swiss guy on a cannon.

In the Prologue to ''Gargantua'' the narrator addresses the: "Most illustrious drinkers, and ''you'' the most precious pox-riddenfor to ''you'' and ''you'' alone are my writings dedicated ..." before turning to Plato's ''

''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' relates the adventures of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The tales are adventurous and erudite, festive and gross, ecumenical, and rarely—if ever—solemn for long. The first book, chronologically, was ''Pantagruel: King of the Dipsodes'' and the Gargantua mentioned in the Prologue refers not to Rabelais' own work but to storybooks that were being sold at the Lyon fairs in the early 1530s. In the first chapter of the earliest book, Pantagruel's lineage is listed back 60 generations to a giant named Chalbroth. The narrator dismisses the skeptics of the time—who would have thought a giant far too large for Noah's Ark—stating that Hurtaly (the giant reigning during the flood and a great fan of soup) simply rode the Ark like a kid on a rocking horse, or like a fat Swiss guy on a cannon.

In the Prologue to ''Gargantua'' the narrator addresses the: "Most illustrious drinkers, and ''you'' the most precious pox-riddenfor to ''you'' and ''you'' alone are my writings dedicated ..." before turning to Plato's ''Banquet

A banquet (; ) is a formal large meal where a number of people consume food together. Banquets are traditionally held to enhance the prestige of a host, or reinforce social bonds among joint contributors. Modern examples of these purposes inc ...

''. An unprecedented syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

epidemic had raged through Europe for over 30 years when the book was published, even the king of France was reputed to have been infected. Etion was the first giant in Pantagruel's list of ancestors to suffer from the disease.

Although most chapters are humorous, wildly fantastic and frequently absurd, a few relatively serious passages have become famous for expressing humanistic ideals of the time. In particular, the chapters on Gargantua's boyhood and Gargantua's paternal letter to Pantagruel present a quite detailed vision of education.

Thélème

In the second novel, ''Gargantua'', M. Alcofribas narrates the Abbey of Thélème, built by the giant Gargantua. It differs markedly from the monastic norm, since it is open to both monks and nuns and has a swimming pool, maid service, and no clocks in sight. Only the good-looking are permitted to enter. The inscription at the gate first specifies who is not welcome: hypocrites, bigots, the pox-ridden, Goths, Magoths, straw-chewing law clerks, usurious grinches, old or officious judges, and burners of heretics. When the members are defined positively, the text becomes more inviting:The Thélèmites in the abbey live according to a single rule:::::Honour, praise, distraction ::::Herein lies subtraction ::::in the tuning up of joy. ::::To healthy bodies so employed ::::Do pass on this reaction: ::::Honour, praise, distraction

DO WHAT YOU WANT

''The Third Book''

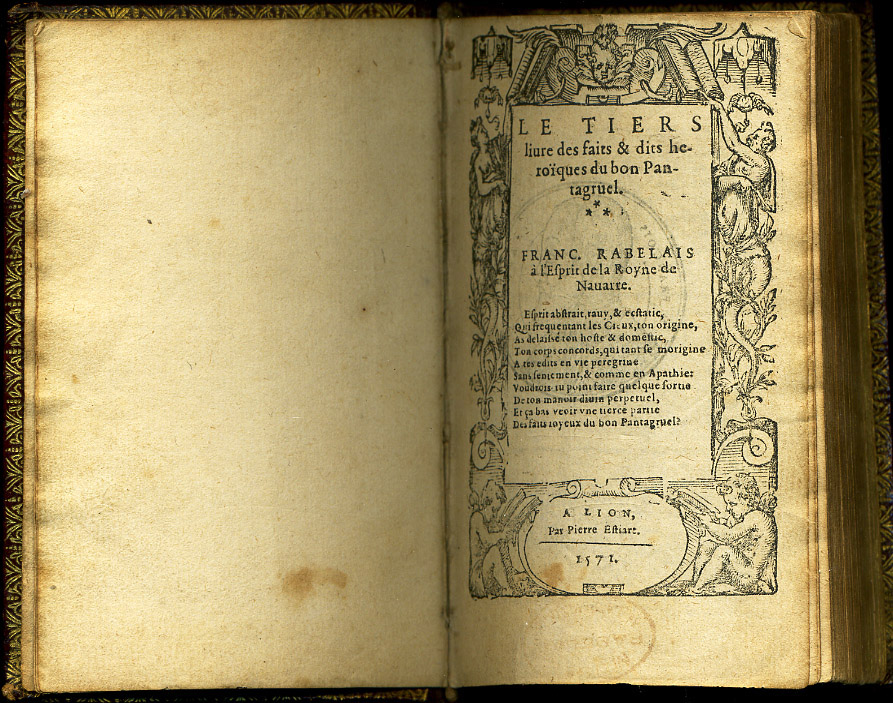

Published in 1546 under his own name with the ''privilège'' granted by Francis I for the first edition and by Henri II for the 1552 edition, ''The Third Book'' was condemned by the Sorbonne, like the previous tomes. In it, Rabelais revisited discussions he had had while working as a secretary to Geoffroy d'Estissac earlier in Fontenay–le–Comte, where ''la querelle des femmes'' had been a lively subject of debate. More recent exchanges with Marguerite de Navarre—possibly about the question of clandestine marriage and the

Published in 1546 under his own name with the ''privilège'' granted by Francis I for the first edition and by Henri II for the 1552 edition, ''The Third Book'' was condemned by the Sorbonne, like the previous tomes. In it, Rabelais revisited discussions he had had while working as a secretary to Geoffroy d'Estissac earlier in Fontenay–le–Comte, where ''la querelle des femmes'' had been a lively subject of debate. More recent exchanges with Marguerite de Navarre—possibly about the question of clandestine marriage and the Book of Tobit

The Book of Tobit (), also known as the Book of Tobias, is a deuterocanonical pre-Christian work from the 3rd or early 2nd century BC which describes how God tests the faithful, responds to prayers, and protects the pre-covenant community (i.e., ...

whose canonical status was being debated at the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

—led Rabelais to dedicate the book to her before she wrote the '' Heptaméron''.

In contrast to the two preceding chronicles, the dialogue between the characters is much more developed than the plot elements in the third book. In particular, the central question of the book, which Panurge and Pantagruel consider from multiple points of view, is an abstract one: whether Panurge should marry or not. Torn between the desire for a wife and the fear of being cuckolded, Panurge engages in divinatory methods, like dream interpretation and bibliomancy. He consults authorities vested with revealed knowledge, like the sibyl of Panzoust or the mute Nazdecabre, profane acquaintances, like the theologian Hippothadée or the philosopher Trouillogan, and even the jester Triboulet. It is likely that several of the characters refer to real people: Abel Lefranc argues that Hippothadée was Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, Rondibilis was the doctor Guillaume Rondelet, the

In contrast to the two preceding chronicles, the dialogue between the characters is much more developed than the plot elements in the third book. In particular, the central question of the book, which Panurge and Pantagruel consider from multiple points of view, is an abstract one: whether Panurge should marry or not. Torn between the desire for a wife and the fear of being cuckolded, Panurge engages in divinatory methods, like dream interpretation and bibliomancy. He consults authorities vested with revealed knowledge, like the sibyl of Panzoust or the mute Nazdecabre, profane acquaintances, like the theologian Hippothadée or the philosopher Trouillogan, and even the jester Triboulet. It is likely that several of the characters refer to real people: Abel Lefranc argues that Hippothadée was Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, Rondibilis was the doctor Guillaume Rondelet, the esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

Her Trippa corresponds to Cornelius Agrippa. One of the comic features of the story is the contradictory interpretations Pantagruel and Panurge get embroiled in, the first of which being the paradoxical encomium

''Encomium'' (: ''encomia'') is a Latin word deriving from the Ancient Greek ''enkomion'' (), meaning "the praise of a person or thing." Another Latin equivalent is '' laudatio'', a speech in praise of someone or something.

Originally was the ...

of debts in chapter III. ''The Third Book'', deeply indebted to ''In Praise of Folly

''In Praise of Folly'', also translated as ''The Praise of Folly'' ( or ), is an essay written in Latin in 1509 by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam and first printed in June 1511. Inspired by previous works of the Italian Renaissance humanism, hu ...

'', contains the first-known attestation of the word ''paradoxe'' in French.

The more reflective tone shows the characters' evolution from the earlier tomes. Here Panurge is not as crafty as Pantagruel and is stubborn in his will to turn every sign to his advantage, refusing to listen to advice he had himself sought out. For example, when Her Trippa reads dark omens in his future marriage, Panurge accuses him of the same blind self-love (''philautie'') from which he seems to suffer. His erudition is more often put to work for pedantry than let to settle into wisdom. By contrast, Pantagruel's speech gains in weightiness by the third book, the exuberance of the young giant having faded.

At the end of the ''Third Book'', the protagonists decide to set sail in search of a discussion with the Oracle of the Divine Bottle. The last chapters are focused on the praise of Pantagruelion, which combines properties of linen and hemp—a plant used in the 16th century for both the hangman's rope and medicinal purposes, being copiously loaded onto the ships. As a naturalist inspired by Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

and Charles Estienne, the narrator intercedes in the story, first describing the plant in great detail, then waxing lyrical on its various qualities.

''The Fourth Book''

Rabelais began work on ''The Fourth Book'' while still in Metz. He dropped off a manuscript containing eleven chapters and ending mid-sentence in Lyon on his way to Rome to work as Cardinal du Bellay's personal physician in 1548. According to Jean Plattard, this publication served two purposes: first, it brought Rabelais some much-needed money; and second, it allowed him to respond to those who considered his work blasphemous. While the prologue denounced slanderers, the following chapters did not raise any polemical issues. Already it contained some of the best-known episodes, including the storm at sea and Panurge's sheep. It was framed as an erratic odyssey, inspired in part by theArgonauts

The Argonauts ( ; ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, ''Argo'', named after it ...

and the news of Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier (; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French maritime explorer from Brittany. Jacques Cartier was the first Europeans, European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, wh ...

's voyage to Canada, and in part by the imaginary voyage described by Lucian

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridi ...

in '' A True Story'', which provided Rabelais not only with several anecdotes, but also with a first-person narrator who regularly insisted on the ''veracity'' of obviously fantastical elements of the story. The full version appeared in 1552, after Rabelais received a royal privilege on 6 Aug 1550 for the exclusive right to publish his work in French, Tuscan, Greek, and Latin. This, he accomplished with the help of the young Cardinal of Châtillon ( Odet de Coligny)—who would later convert to Protestantism and be excommunicated. Rabelais thanks the Cardinal for his help in the prefatory letter signed 28 January 1552 and, for the first time in the Pantagruel series, titled the prologue in his own name rather than using a pseudonym.

Use of language

The French Renaissance was a time of linguistic contact and debate. The first book of French, rather than Latin, grammar was published in 1530, followed nine years later by the language's first dictionary. Spelling was far less codified. Rabelais, as an educated reader of the day, preferredetymological

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

spelling—preserving clues to the lineage of words—to more phonetic spellings which wash those traces away.

Rabelais' use of Latin, Greek, regional and dialectal terms, creative calquing, gloss, neologism

In linguistics, a neologism (; also known as a coinage) is any newly formed word, term, or phrase that has achieved popular or institutional recognition and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered ...

and mis-translation was the fruit of the printing press having been invented less than a hundred years earlier. A doctor by trade, Rabelais was a prolific reader, who wrote a great deal about bodies and all they excrete or ingest. His fictional works are filled with multilingual, often sexual, puns, absurd creatures, bawdy songs and lists. Words and metaphors from Rabelais abound in modern French and some words have found their way into English, through Thomas Urquhart

Sir Thomas Urquhart (1611–1660) was a Scottish aristocrat, writer, and translator. He is best known for his translation of the works of French Renaissance writer François Rabelais to English.

Biography

Urquhart was born to Thomas Urquhar ...

's unfinished 1693 translation, completed and considerably augmented by Peter Anthony Motteux by 1708. According to Radio-Canada, the novel ''Gargantua'' permanently added more than 800 words to the French language.

Scholarly views

Most scholars today agree that Rabelais wrote from a perspective of Christian humanism. This has not always been the case. Abel Lefranc, in his 1922 introduction to ''Pantagruel'', depicted Rabelais as a militant anti-Christian atheist. On the contrary, M. A. Screech, like Lucien Febvre before him, describes Rabelais as an Erasmian. While formally aRoman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

, Rabelais was a humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

, and favoured classical Antiquity over the "barbarous" Middle Ages, believing in the need for reform to return science and arts to their classical blossoming, and theology and the Church to their original Evangelical form as expressed in the Gospels. In particular, he was critical of monasticism

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Chr ...

. Rabelais criticised what he considered to be inauthentic Christian positions by both Catholics and Protestants, and was attacked and portrayed as a threat to religion or even an atheist by both. For example, "at the request of Catholic theologians, all four Pantagrueline chronicles were censured by either the Sorbonne, Parlement, or both". On the opposite end of the spectrum, John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

saw Rabelais as a representative of the numerous moderate evangelical humanists who, while "critical of contemporary Catholic institutions, doctrines, and conduct", did not go far enough; in addition, Calvin considered Rabelais' apparent mocking tone to be especially dangerous, since it could be easily interpreted as a rejection of the sacred truths themselves.

Timothy Hampton writes that "to a degree unequaled by the case of any other writer from the European Renaissance, the reception of Rabelais's work has involved dispute, critical disagreement, and ... scholarly wrangling ..." In particular, as pointed out by Bruno Braunrot, the traditional view of Rabelais as a humanist has been challenged by early post-structuralist

Post-structuralism is a philosophical movement that questions the objectivity or stability of the various interpretive structures that are posited by structuralism and considers them to be constituted by broader systems of Power (social and poli ...

analyses denying a single consistent ideological message of his text, and to some extent earlier by Marxist critiques such as Mikhail Bakhtin

Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (; rus, Михаи́л Миха́йлович Бахти́н, , mʲɪxɐˈil mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bɐxˈtʲin; – 7 March 1975) was a Russian people, Russian philosopher and literary critic who worked on the phi ...

with his emphasis on the subversive folk roots of Rabelais' humour in medieval "carnival

Carnival (known as Shrovetide in certain localities) is a festive season that occurs at the close of the Christian pre-Lenten period, consisting of Quinquagesima or Shrove Sunday, Shrove Monday, and Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras.

Carnival typi ...

" culture. At present, however, "whatever controversy still surrounds Rabelais studies can be found above all in the application of feminist theories to Rabelais criticism", as he is alternately considered a misogynist or a feminist based on different episodes in his works.

An article by Edwin M. Duvall in ''Études rabelaisiennes'' 18 (1985) sparked a debate on the prologue of ''Gargantua'' in the pages of the ''Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France'' as to whether Rabelais intentionally hid higher meanings in his work, to be discovered through erudition and philology, or if instead the polyvalence of symbols was a poetic device meant to resist the reductive gloss.

suggests that Panurge's description (in the Papimane Island episode in ''The Fourth Book'') of the ill-effects of the pages of decretal

Decretals () are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in canon law (Catholic Church), ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10

They are generally given in answer to consultations but are some ...

s being used as toilet paper, targets, cones, and masks on whatever they touch was due to their misuse as material objects. As the merry crew sail on from the island towards the Divine Bottle, in the subsequent episode, Pantagruel is content simply listening to the thawing words as they rain down on the boat, whereas Jeanneret observes that his companions focus instead on their colourful appearance while they are still frozen, hurrying to gather as many up as they can and offering to sell those they have collected. The pilot describes the words as evidence of a great battle, and the narrator even wants to preserve some of the finest insults in oil. Jeanneret observes that Pantagruel considers the exchange of words to be an act of love rather than a commercial exchange, argues that their artificial preservation is superfluous, and "insinuates that books are petrified tombs, where the signs threaten to stop moving and, left to the devices of lazy readers, get shriveled down into simplistic meanings implying that " l writing carries within it the danger of the Decretals."

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

'' of 1911 declared that Rabelais was

... a revolutionary who attacked all the past, Scholasticism, the monks; his religion is scarcely more than that of a spiritually minded pagan. Less bold in political matters, he cared little for liberty; his ideal was a tyrant who loves peace. ..His vocabulary is rich and picturesque, but licentious and filthy. ....As a whole it exercises a baneful influence.

In literature

Acknowledging both the sordid side of the work and its protean nature, Jean de La Bruyère in 1688 saw beyond that its sublimity:His book is an enigma, it is whatever you want to say, it is inexplicable, it is a chimera ….. a monstrous assembling of refined and ingenious morality and foul corruption. Either it is bad, sinking far below the worst, to have the charm of the rabble. Or it is good, rising as far as exquisite and excellent, to be perhaps the most delicious of dishes.In his 1759–1767 novel '' Tristram Shandy'', Laurence Sterne quotes extensively from Rabelais. Alfred Jarry performed, from memory, hymns of Rabelais at Symbolist Rachilde's Tuesday salons, and worked for years on an unfinished

libretto

A libretto (From the Italian word , ) is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to th ...

for an opera by Claude Terrasse based on Pantagruel. Anatole France

(; born ; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters.John Cowper Powys

John Cowper Powys ( ; 8 October 187217 June 1963) was an English novelist, philosopher, lecturer, critic and poet born in Shirley, Derbyshire, where his father was vicar of the parish church in 1871–1879. Powys appeared with a volume of verse ...

, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis, and Lucien Febvre

Lucien Paul Victor Febvre ( ; ; 22 July 1878 – 11 September 1956) was a French historian best known for the role he played in establishing the Annales School of history. He was the initial editor of the ''Encyclopédie française'' together wit ...

(one of the founders of the French historical school ''Annales

Annals are a concise form of historical writing which record events chronologically, year by year. The equivalent word in Latin and French is ''annales'', which is used untranslated in English in various contexts.

List of works with titles contai ...

''), all wrote books about him.

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

included an allusion to "Master Francois somebody" in his 1922 novel '' Ulysses''.

Mikhail Bakhtin

Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (; rus, Михаи́л Миха́йлович Бахти́н, , mʲɪxɐˈil mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bɐxˈtʲin; – 7 March 1975) was a Russian people, Russian philosopher and literary critic who worked on the phi ...

, a Russian philosopher and critic, derived his concepts of the carnivalesque

The Carnivalesque is a literary mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor and chaos. It originated as "carnival" in Mikhail Bakhtin's ''Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics'' and was further dev ...

and grotesque body from the world of Rabelais. He points to the historical loss of communal spirit after the Medieval period and speaks of carnival laughter as an "expression of social consciousness".

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley ( ; 26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. His bibliography spans nearly 50 books, including non-fiction novel, non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the ...

admired Rabelais' work. Writing in 1929, he praised Rabelais, stating "Rabelais loved the bowels which Swift

Swift or SWIFT most commonly refers to:

* SWIFT, an international organization facilitating transactions between banks

** SWIFT code

* Swift (programming language)

* Swift (bird), a family of birds

It may also refer to:

Organizations

* SWIF ...

so malignantly hated. His was the true amor fati

is a Latin phrase that may be translated as "love of fate" or "love of one's fate". It is used to describe an attitude in which one sees everything that happens in one's life, including suffering and loss, as good or, at the very least, necessa ...

: he accepted reality in its entirety, accepted with gratitude and delight this amazingly improbable world."

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

was not an admirer of Rabelais. Writing in 1940, he called him "an exceptionally perverse, morbid writer, a case for psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

". Milan Kundera

Milan Kundera ( ; ; 1 April 1929 – 11 July 2023) was a Czech and French novelist. Kundera went into exile in France in 1975, acquiring citizenship in 1981. His Czechoslovak citizenship was revoked in 1979, but he was granted Czech citizenship ...

, in a 2007 article in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'', commented on a list of the most notable works of French literature, noting with surprise and indignation that Rabelais was placed behind Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

's war memoirs, and was denied the "aura of a founding figure! Yet in the eyes of nearly every great novelist of our time he is, along with Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his no ...

, the founder of an entire art, the art of the novel". In the satirical musical ''The Music Man

''The Music Man'' is a musical theatre, musical with book, music, and lyrics by Meredith Willson, based on a story by Willson and Franklin Lacey. The plot concerns a confidence trick, con man Harold Hill, who poses as a boys' band organizer and ...

'' by Meredith Willson, the names "Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

! Rabelais! Balzac!" are presented by local gossips as evidence that the town librarian "advocates dirty books."

Rabelais is a pivotal figure in Kenzaburō Ōe's 1994 acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

.

Honours, tributes and legacy

* The public university inTours, France

Tours ( ; ) is the largest city in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the prefecture of the department of Indre-et-Loire. The commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabitants as of 2018 while the population of the whole metropolitan ar ...

, was named Université François Rabelais during 40 years, until 2018.

* Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

was inspired by the works of Rabelais to write Les Cent Contes Drolatiques (The Hundred Humorous Tales). Balzac also pays homage to Rabelais by quoting him in more than twenty novels and the short stories of La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy). Michel Brix wrote of Balzac that he "is obviously a son or grandson of Rabelais... He has never hidden his admiration for the author of Gargantua

''La vie tres horrifique du grand Gargantua, père de Pantagruel jadis composée par M. Alcofribas abstracteur de quinte essence. Livre plein de Pantagruelisme'' according to 's 1542 edition, or simply Gargantua, is the second novel by François ...

, whom he cites in Le Cousin Pons as "the greatest mind of modern humanity". In his story of ''Zéro, Conte Fantastique'' published in La Silhouette on 3 October 1830, Balzac even adopted Rabelais's pseudonym (''Alcofribas'').

* There is a tradition at the University of Montpellier

The University of Montpellier () is a public university, public research university located in Montpellier, in south-east of France. Established in 1220, the University of Montpellier is one of the List of oldest universities in continuous opera ...

's Faculty of Medicine: no graduating medic can undergo a convocation without taking an oath under ''Rabelais's robe''. Further tributes are paid to him in other traditions of the university, such as its '' faluche'', a distinctive student headcap which in Montpellier is styled in his honour, with four bands of colour emanating from its centre.

* Asteroid '5666 Rabelais' was named in honor of François Rabelais in 1982.

* In Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio's 2008 Nobel Prize lecture, Le Clézio referred to Rabelais as "the greatest writer in the French language".

* In France the moment at a restaurant when the waiter presents the bill is still sometimes called ''le quart d'heure de Rabelais'' (The fifteen minutes of Rabelais), in memory of a famous trick Rabelais used to get out of paying a tavern bill.

*

Works

*Gargantua and Pantagruel

''The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel'' (), often shortened to ''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' or the (''Five Books''), is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais. It tells the advent ...

, a series of four or five books including:

** '' (1532)

** ''La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua'', usually called ''Gargantua

''La vie tres horrifique du grand Gargantua, père de Pantagruel jadis composée par M. Alcofribas abstracteur de quinte essence. Livre plein de Pantagruelisme'' according to 's 1542 edition, or simply Gargantua, is the second novel by François ...

'' (1534)

** '' Gargantua and Pantagruel#The Third Book'' (1546)

** '' The Fourth Book'' (1552)

** ' (1564) whose authorship is contested

*' (1532, 1533, 1535, 1537, 1542 ): parodic almanac, astrology

*' (1549): description of the festivities organized by Jean du Bellay to celebrate the birth of Louis of Valois

See also

* '' Rabelais and His World'' *Thomas Urquhart

Sir Thomas Urquhart (1611–1660) was a Scottish aristocrat, writer, and translator. He is best known for his translation of the works of French Renaissance writer François Rabelais to English.

Biography

Urquhart was born to Thomas Urquhar ...

* Peter Anthony Motteux, (works at wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

)

* The Great Mare

* Rabelais Student Media

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

;General * * * * * * ;Commentary * * * * * * * * ; Complete works * *Further reading

* * * * * * O’Brien, John (2019), Jennings, Jeremy; Moriarty, Michael (eds.), "Rabelais", ''The Cambridge History of French Thought'', Cambridge University Press, pp. 47–54External links

* * *Rabelais.nl

sur l

Portail de la Renaissance française

François Rabelais Museum on the Internet

* Henry Émile Chevalier, , 1868 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rabelais, Francois 1553 deaths 15th-century births 16th-century French male writers 16th-century French novelists 16th-century French physicians 16th-century French writers 16th-century Roman Catholics French Benedictines French Franciscans French Renaissance humanists French Renaissance French Roman Catholic writers French male novelists French male poets French medical writers People from Indre-et-Loire Thelema University of Montpellier alumni University of Poitiers alumni Writers from Centre-Val de Loire